Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Eip Final

Caricato da

api-341007110Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Eip Final

Caricato da

api-341007110Copyright:

Formati disponibili

Lawe 1

Thomas Lawe

Malcolm Campbell

UWRT 1103

9 November 2016

But He was Only a Kid: Why Police Use Lethal Force

On September 20th, 2016 Keith Lamont Scott was shot dead by Officer Brentley Vinson

of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg police. His family claims that he was innocent of any crime, that

he was shot dead for being black while waiting to pick up his daughter. The police account of

the shooting reports that Scott had a gun, refused to comply with officers, and was an imminent

threat to the life of the officers attempting to arrest him for possession of marijuana and an

illegally obtained gun. The district attorney has yet to bring the case before a grand jury for

indictment, but for several days afterwards there where major protests and riots in the city.

Whatever the result of the investigation, Keith Lamont Scott is not the first person to die at the

hands of police in the last year, or even the hundredth. Between 458 and over a thousand people

are killed by US police forces annually. It is difficult to know for sure the exact number because

the Department of Justice does not require police departments to report all officer involved

shootings. Some of the others killed by police are familiar to the public: Michael Brown, Eric

Garner, Tamir Rice, or any of the dozens of others in the news recently. Others died out of the

public eye, like Rekia Boyd, Aki Gurley, Antonio Zambrano-Montes, and literally hundreds of

others (Deadly). Every week it seems that one someone dies at the hands of police, justified or

not, and their deaths bring civil unrest and a host of questions. Why do police resort to lethal

force so frequently? Is it training? Is it more common with minorities? Who is responsible for

these deaths? From CNN to the White House to Amnesty International, people are searching for

Lawe 2

the answers to these questions and a way to end the bloodshed. Psychologists and sociologists

have been working for literal decades to examine the reasons for the differences in police

treatment of minorities.

The frequent lethality of American police forces stem from three major

areas: poor accountability, some degree of racial bias, and high stress decision making coupled

with less than stellar training.

What happens when an officer kills someone while on the job? Due to the nature of

police forces in the US, there is no universal procedure for determining whether the use of lethal

force was justified. In fact, in nine states and Washington D.C. there are no legal statutes

relating to police use of lethal force. In other states, the statutes are so vague and weak that they

might as well be nonexistent (Deadly). However, there are common procedures in most police

departments that are not legally required or enforced following a shooting by an officer. Most

are similar to the procedure for dealing with an officer involved shooting in North

Carolina. First, the officer in question is relieved of his weapon, which is put in evidence. The

officer is then sequestered in the police station and is supposed to speak to no one except his/her

attorney. The investigation of the shooting is treated as any other homicide would: evidence is

collected, witnesses interviewed, the officer makes a statement. As far as most courts are

concerned, the word of a sworn officer of the law is worth more than the word of a non-law

enforcement witness(Deadly). Eyewitness testimonies are notorious for their unreliability, six

different people will give six different accounts of something as simple as a fender bender, never

mind a violent confrontation with police (Blink 43). Still, in courts the oaths sworn by police

officers seem to hold more value than the evidence of faulty human memory from the way

officers testimonies are treated (Deadly). The collected information is given the District

Attorney, who decides whether to bring the case before a Grand Jury. It should be noted,

Lawe 3

however, that the District Attorney is a person who is deeply involved in police business;

anything that reflects poorly on police officers reflects poorly on the district attorney. If the

Grand Jury indicts then a trial begins (NC Law). This is undoubtedly a flawed procedure; at

no point does the investigation involve any organization outside the police, at no point do higher

authorities take over the investigation from the police, at no point is the department held

accountable to anyone other than the DA, who frequently has a long and cordial history with the

local police department. An officer of the law killing a person, innocent or guilty, without trial is

a major event and should be treated as such, but the Department of Justices does not even collect

information on when officer involved shootings occur. In fact, the lackadaisical approach to law

enforcement accountability in the United States fails to comply with international standards set

by the United Nations (Deadly). The United Nations Basic Principles on the Use of Force

and Firearms restricts the use of lethal force to the defense of self or others against immediate

threats of serious injury or death. To quote the document intentional lethal use of firearms may

only be made when strictly unavoidable in order to protect life (qtd. In Deadly). In all US

states, lethal force can be used against escaping prisoners, even nonviolent ones. Police officers

are trained, when using lethal force, to empty their firearms magazine before they stop firing

(NC Law). Most police forces in the US use firearms with 12-13 bullet magazines, so in any

confrontation 12-13 bullets will hit the suspect, the inanimate objects surrounding the suspect,

and innocent bystanders. In virtually every case where someone is shot by police less than

twelve times, the remaining bullets hit someone or something else. Not only is firing 12 bullets

into a suspect a far beyond what is strictly necessary and proportional in the eyes of the UN,

the potential for collateral damage and hurting innocents is well outside the UNs acceptable

standards from The United Nations Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms

Lawe 4

(Deadly). Even supposedly nonlethal weapons used by police officers are deadly weapons

if something goes wrong. Between 2001 and 2012, over 540 people died after a police officer

used a Taser on them. Nightsticks and rubber bullets can kill if they hit the head or torso wrong

by causing brain damage, broken bones or ruptured internal organs. Tear gas and pepper spray

can cause scarring of the cornea of the eye, blinding a person permanently, they can cause

chemical burns on skin contact, they can cause a person with preexisting medical conditions to

go into respiratory arrest and die. Getting hit in the head with a tear gas canister will kill more

often than not. Under the Geneva Protocols, using tear gas against enemy soldiers would be a

war crime, yet police officers can use it of protesters dont have a license for their rally

(Deadly). Even fewer restrictions exist surrounding the use of nonlethal less-lethal weaponry

by police than exist for firearms, despite the way all less lethal weapons are still lethal and fall

under The United Nations Basic Principles on the Use of Force (Deadly, NC Law). Police

forces in the United States dont meet international standards; nine dont even meet

constitutional standard of No person shall be [] deprived of life, liberty, or property, without

due process of the law; since the law has no process for police use of lethal force (Deadly).

Some communities across the country have tried to provide some control with non-police related

accountability groups. Citizen review boards, civilian oversight committees, Offices of

community Complaints, and other similarly named groups attempt to provide accountability

lacking in the legislature. The idea first appeared inNYC in 1965 to stem complaints about

police misconduct to minority groups. It failed there, but the idea caught on across the country

(Kaste). The idea of policing the police through civilian groups seems great, but it has its own

problems. Who get to be on this bored? In the City of Charlotte, the 11 member Citizens

Review Board is made up of appointed members, 3 by the mayor, 5 by the City Counsel, and 3

Lawe 5

by the City Manager who all have up to two terms of 3 years to review appeals by citizens

against the police. In the 18 years the Citizens Review Board has existed, they ruled in favor of

the police every single time (Wright). Either the Charlotte Mecklenburg Police department has

never overused force, profiled a suspect, or otherwise been objectionable, or the Review Board

has failed to do its job. This is not unusual. There are less than 300 active citizen review boards

across the US, which according to Mark Silverstein of the ACLU, range from very weak to

somewhat effective (qtd. In Wright, Kaste). When a board is run by the same groups that run

the police, has no power to investigate complaints directly, has closed door meetings, and has a

higher standard of evidence than the police change is hard to create (Kaste, Wright). So, what

happens when a police officer kills someone while on the job? All too frequently a great sound

and fury, signifying nothing. How many people always do the right thing when no one is

watching? How many would hit another in anger, if they were sure their justified version of

events would be believed? What makes a police officer different than anyone else? Without

oversight and supervision people make mistakes or take advantage of the system. From

something as harmless as looting an entire candy bowl on Halloween instead of taking two

pieces to escalating an attempted arrest to a violent altercation, people will do what they want

when there are no consequences. If the legislative bodies of the United States and its component

states will not strengthen the laws regulating police, then cities should strengthen citizen

oversight from a token gesture to an actual force. A review board with the power and funding to

investigate the police, made up of elected members not appointed by city governments, would

have the power to force police accountability to the citizens they are meant to protect. Instead of

buying a military surplus armored transport for the riot squad, why not fund a citizen review

board to prevent the riot in the first place?

Lawe 6

"They shot my daddy 'cause he's black[]." These words were spoken by Lyric Scott,

daughter of Keith Lamont Scott, seconds after hearing of her fathers death. It isnt an

uncommon sentiment, its a part of the birth of the Black Lives Matter movement. Enough

people believed that statement to be true to participate in protests that became riots in the

Charlotte area following Lamonts death (Shoichet). How much truth is there in this sentiment?

Quite a lot, argues Kimberly Kahn in her paper How Suspect Race Affects Police Use Of Force

In An Interaction Over Time for the journal Law and Human Behavior. Kahn examined police

reports on use of force, and found that when officers knew nothing about a suspect other than

their race, they were more likely to escalate into use of force for minorities especially African

Americas and Latinos than if the suspect was white. At the same time, Kahn found that white

suspects are more likely to escalate a situation to require force without an officer using force first

(Kahn). This is a clear indication of racial bias in police officers. Not all officers, and not

everywhere, but enough to make a statistical difference. If officers had not attempted to smash

the passenger window of Scotts car with a baton during the arrest, he might have reacted

differently. Would officers have done the same thing for a white man smoking a joint of

marijuana and who may have had a gun (Shoichet)? Whether the racial bias of police forces is

conscious or not, approved or not, and institutional or not, it is statistically present. If police are

more likely to jump to force sooner, then more people are going to resist violently. If more

people resist police violently, then more people are going to be hurt or killed in their attempt.

Did Officer Brentley Vinson of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg police kill Keith Lamont Scott

because he was black? Probably not. Vinson is African American as well. Did Vinson and his

fellow officers treat Scotts attempted arrest differently because he was black? Likely they did,

and that probably caused Scott to act in the way that the officers felt they needed to use lethal

Lawe 7

force for the safety of themselves and others. Racism is one of the most enduring problems in

the US, and there is no simple solution. Yes, police are less institutionally racist today than they

were in the 1960s, but that is the result cultural change in the nation as a whole and the civil

rights movement, not by a policy change by police (Deadly, Shoichet). One action that may

help alleviate the symptoms of institutional racism, if not the cause , is the passage of the End

Racial Profiling Act. The act seeks to bring US standards for defining institutional racism with

the United Nations definition. According to the International Covenant on Civil and Political

Rights (ICCPR) and the International Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Racial

Discrimination (ICERD), policies that are discriminatory in act, no matter the intention, are

prohibited. As the law stands now, the US Court system can only end an institutionally racist

policy if the intent can be proven racist, no matter the end result by officers. The End Racial

Profiling Act would bridge the gap between these two definitions, giving federal courts the

ability to strike down even unintentionally institutionally racist policies.

Any situation where one person kills or may kill another reaches any definition of high

stress situation. What happens when a person is in a high stress situation and must make a life

and death decision? Adrenaline floods the brain, suppressing more complex thought in favor of

shorter reaction times, pattern recognition, and the flight or fight response (Gladwell 5). That is

all well and good for an animal fighting for survival in the forest, but for a civilized human being

charged with upholding the foundation of civilization that response causes nothing but

trouble. In his book Blink, Malcolm Gladwell argues that a sufficiently trained expert can make

decisions in an instant that are as good or better than carefully thought out ones (Gladwell

2). What that level of training for an expert is, Gladwell does not make clear, but police do not

have it. Its not all that surprising really, given that in the state of North Carolina a person

Lawe 8

spends more time training to be a licensed barber than a law enforcement officer (Deadly,

Yan). In the State of Massachusetts a refrigerator technician must undergo 1,000 hours of

training to be trusted to fix an appliance, but police officers are given a gun and badge after 900

hours of training. In Louisiana, a police officer must undergo only 360 hours of training before

hitting the streets; in the same place a manicurist must be trained for at least 500 hours before

getting a license to work (Yan). Clearly there is a problem with the system when a person is

trusted with a gun and the right to use it before they are trusted to work on the public with nail

files and polish. Gladwell agrees in Blink, where one of the few examples of snap judgements

gone wrong is the 1999 killing of Amadou Diallo. Four NYC Police officers demanded Diallo

stop and put his hands in the air, believing him to be a serial rapist or the rapists lookout. Diallo

did not stop or show his hands, instead pulling out his wallet. One officer, Sean Carroll, saw

Diallo reach for something small and square, shouted GUN and began shooting at Diallo. The

four officers fired 42 shots, 19 of which hit Diallo. Diallo was innocent of any crime (Gladwell

105). Perhaps if the officers in question had been better trained, then the shooting would not

have happened. Perhaps if Diallo had complied instantly, the officers in question would not have

felt the need to fire on him. Either way, this situation only highlights the way people behave

irrationally on both sides of a high stress situation.

Police officers work long hours for long work weeks. They are public servants, meant to

enforce the laws and serve the greater good. They are also people, just like anyone else. They

are fallible. When they make a mistake, people can die. Sometimes they do everything correctly

and people die anyway. Sometimes, they must kill someone in the line of duty. Sometimes they

dont or shouldnt, but they still kill someone. Poor accountability and poorly defined

regulations make justified use of lethal force a hazy idea in the best of times. High stress

Lawe 9

decision making and insufficient training can lead to police officers making the wrong call in the

heat of the moment, and using lethal force without proper justification. Racial bias in police

forces make people wary of police, seeing that police are more likely to use nonlethal forcebut

force nonethelessagainst minorities. Some of these people are going to use force right back at

the police, which can quickly escalate to police using lethal force against a dangerous suspect.

Lawe 10

Works Cited

Deadly Force: Police use of Lethal Force in the United States. Lethal Force: Amnesty

International USA. New York: Amnesty International Publications, 2015. Web. 4

November 2016

Gladwell, Malcolm. Blink: The Power of Thinking without Thinking. New York: Little, Brown,

2005. Print.

Kahn, Kimberly Barsamian, et al. "How Suspect Race Affects Police Use Of Force In An

Interaction Over Time." Law And Human Behavior (2016): PsycARTICLES. Web. 22

Oct. 2016.

Kaste, Martin. "Police Are Learning To Accept Civilian Oversight, But Distrust Lingers."

Weekend Edition Saturday: Law. NPR, 21 Feb. 2015. Web. 03 Dec. 2016.

"NC Law Details When Law Enforcement Can Use Deadly Force ..."CBS North Carolina. CBS,

1 Mar. 2016. Web. 14 Oct. 2016.

Shoichet, Catherine. "Keith Lamont Scott: What We Know about Man Shot by Charlotte Police."

Keith Lamont Scott: What We Know. CNN, 23 Sept. 2016. Web. 07 Nov. 2016.

Wright, Gary, and Fred Clasen-Kelly. "CMPD Review Panel Rules against Citizens - Every

Time." Charlotte Observer -- Crime. The Charlotte Oberver, 16 Feb. 2013. Web. 03 Dec.

2016.

Yan, Holly. "States Require More Training Time to Become a Barber than a Police

Officer." CNN. Cable News Network, 28 Sept. 2016. Web. 04 Nov. 2016.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Bad Cop Psychopathy & Protective Politics: The Misuse of Force and PowerDa EverandBad Cop Psychopathy & Protective Politics: The Misuse of Force and PowerNessuna valutazione finora

- Eip Edits FinalDocumento12 pagineEip Edits Finalapi-341007110Nessuna valutazione finora

- Eip Peer ReviewDocumento7 pagineEip Peer Reviewapi-341007110Nessuna valutazione finora

- How The Supreme Court Lets Cops Get Away With MurderDocumento6 pagineHow The Supreme Court Lets Cops Get Away With MurderMaya PosecznickNessuna valutazione finora

- Homicide Investigation-A Practical Handbook-Burt RappDocumento91 pagineHomicide Investigation-A Practical Handbook-Burt Rappcliftoncage100% (2)

- Research Paper Topics On Police BrutalityDocumento4 pagineResearch Paper Topics On Police Brutalityafmcwqkpa100% (1)

- Are The Police Actually BrutalDocumento8 pagineAre The Police Actually Brutalapi-270874509Nessuna valutazione finora

- Emalee Schneider ENG 101 7 November 17 "Thetic" Essay Rough Draft Police BrutalityDocumento5 pagineEmalee Schneider ENG 101 7 November 17 "Thetic" Essay Rough Draft Police Brutalityapi-376274311Nessuna valutazione finora

- Patricia Mendoza Thesis Paper UWRT 1100-1104 April 28th, 2017Documento10 paginePatricia Mendoza Thesis Paper UWRT 1100-1104 April 28th, 2017api-357316107Nessuna valutazione finora

- Exploratory Essay Rough DraftDocumento8 pagineExploratory Essay Rough Draftapi-241333758Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Syllabus For Students When Dealing With Law EnforcementDocumento2 pagineA Syllabus For Students When Dealing With Law EnforcementNathan Bowling100% (1)

- LizardoDocumento7 pagineLizardoMarlo Lao BernasolNessuna valutazione finora

- Extemporaneous SpeechDocumento15 pagineExtemporaneous SpeechHaisoj Leintho SalupNessuna valutazione finora

- Police Brutality Thesis SentenceDocumento7 paginePolice Brutality Thesis Sentencesuejonessalem100% (2)

- Custodial DeathDocumento8 pagineCustodial Deathanuc07100% (2)

- Intro To Death PenaltyDocumento3 pagineIntro To Death PenaltyJannoah Gulleban100% (1)

- Rsearch PaperDocumento11 pagineRsearch Paperapi-301049033Nessuna valutazione finora

- Police Brutality By: Ochs, Holona L. Gonzalzles, Kuroki M. Salem Press Encyclopedia. 6p. Police BrutalityDocumento7 paginePolice Brutality By: Ochs, Holona L. Gonzalzles, Kuroki M. Salem Press Encyclopedia. 6p. Police BrutalityAlaa Rashed100% (1)

- Problem ReportDocumento9 pagineProblem Reportapi-296883349Nessuna valutazione finora

- Know Your Rights - Fight Police CorruptionDocumento14 pagineKnow Your Rights - Fight Police CorruptionSalish Sea Athenaeum100% (2)

- Arguments Against Death PenaltyDocumento3 pagineArguments Against Death PenaltyJulius AlcantaraNessuna valutazione finora

- Police Brutality-7140330Documento2 paginePolice Brutality-7140330api-533839695Nessuna valutazione finora

- Arguement Essay Police Draft 3Documento6 pagineArguement Essay Police Draft 3Nathan SchroederNessuna valutazione finora

- Sequence IIIDocumento6 pagineSequence IIIapi-534751399Nessuna valutazione finora

- Resources On Police BrutalityDocumento15 pagineResources On Police Brutalityapi-450498083Nessuna valutazione finora

- WalteraparugumentDocumento5 pagineWalteraparugumentapi-356610052Nessuna valutazione finora

- Dissertation On Police BrutalityDocumento4 pagineDissertation On Police BrutalityPaperWritingHelpOnlineSingapore100% (1)

- Research-Paper 3Documento10 pagineResearch-Paper 3api-302935815100% (1)

- Seniorpaper AdrianamartinezDocumento9 pagineSeniorpaper Adrianamartinezapi-316838109Nessuna valutazione finora

- Softmore Advocacy Final Draft 1Documento7 pagineSoftmore Advocacy Final Draft 1api-341090482Nessuna valutazione finora

- (How To) Find Out Who's A SnitchDocumento18 pagine(How To) Find Out Who's A SnitchGeo PaulerNessuna valutazione finora

- Blue Code of SilenceDocumento8 pagineBlue Code of SilenceJimmy BernierNessuna valutazione finora

- Four Steps To Curbing Police Misconduct in The United StatesDocumento7 pagineFour Steps To Curbing Police Misconduct in The United StatesLaw Office of Jerry L. SteeringNessuna valutazione finora

- NYT The George Floyd Protests Won't Stop Until Police Brutality DoesDocumento2 pagineNYT The George Floyd Protests Won't Stop Until Police Brutality DoesAntariksha PattnaikNessuna valutazione finora

- Police Brutality Research Thesis StatementDocumento4 paginePolice Brutality Research Thesis StatementPayToWriteAPaperCanada100% (2)

- Dispelling - The - Myths - July18 (1) - 1 PDFDocumento20 pagineDispelling - The - Myths - July18 (1) - 1 PDFKiera StaffordNessuna valutazione finora

- Paper FourDocumento7 paginePaper Fourapi-302275287Nessuna valutazione finora

- ResearchreportavaldezDocumento15 pagineResearchreportavaldezapi-357064476Nessuna valutazione finora

- Utahs Stop and Frisk - Cody AndersonDocumento6 pagineUtahs Stop and Frisk - Cody Andersonapi-92902411Nessuna valutazione finora

- Capital Punishment Vs Life ImprisonmentDocumento2 pagineCapital Punishment Vs Life ImprisonmentYash GautamNessuna valutazione finora

- Hannah Reed Engl Paper - FinalDocumento10 pagineHannah Reed Engl Paper - Finalapi-301667521Nessuna valutazione finora

- Here Are 8 Stubborn Facts On Gun Violence in AmericaDocumento10 pagineHere Are 8 Stubborn Facts On Gun Violence in AmericawholesoulazNessuna valutazione finora

- Argumentative Thesis Statement On Police BrutalityDocumento6 pagineArgumentative Thesis Statement On Police Brutalitycathybaumgardnerfargo100% (2)

- Capital Punishment Essay 2Documento2 pagineCapital Punishment Essay 2api-255110891Nessuna valutazione finora

- Surprising New Evidence Shows Bias in Police Use of Force But Not in Shootings - The New York Times July 11, 2016Documento3 pagineSurprising New Evidence Shows Bias in Police Use of Force But Not in Shootings - The New York Times July 11, 2016Stan J. CaterboneNessuna valutazione finora

- Extrajudicial KillingDocumento4 pagineExtrajudicial KillingJave Mike AtonNessuna valutazione finora

- Positions PaperDocumento9 paginePositions Paperapi-238823212100% (1)

- Final CJ PaperDocumento9 pagineFinal CJ Paperapi-253223969Nessuna valutazione finora

- Leo16 Fryer PDFDocumento62 pagineLeo16 Fryer PDFCarlos AndradeNessuna valutazione finora

- Written Statement of AG Barr - HJC - 07 28 20Documento6 pagineWritten Statement of AG Barr - HJC - 07 28 20Fox News91% (44)

- Written Statement of William P. BarrAttorney GeneralCommittee On The JudiciaryU.S. House of RepresentativesDocumento6 pagineWritten Statement of William P. BarrAttorney GeneralCommittee On The JudiciaryU.S. House of RepresentativesJim Hoft100% (4)

- How Police Are Using Stop & FriskDocumento3 pagineHow Police Are Using Stop & FriskalexamadorNessuna valutazione finora

- Final Ferguson Report Released by AmnestyDocumento20 pagineFinal Ferguson Report Released by AmnestySt. Louis Public RadioNessuna valutazione finora

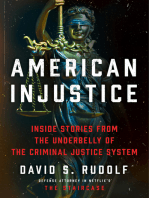

- American Injustice: One Lawyer's Fight to Protect the Rule of LawDa EverandAmerican Injustice: One Lawyer's Fight to Protect the Rule of LawValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2)

- Say Their Names: 101 Black Unarmed Women, Men and Children Killed By Law EnforcementDa EverandSay Their Names: 101 Black Unarmed Women, Men and Children Killed By Law EnforcementNessuna valutazione finora

- Regulating Gun Sales: An Excerpt from Reducing Gun Violence in America, Informing Policy with Evidence and AnalysisDa EverandRegulating Gun Sales: An Excerpt from Reducing Gun Violence in America, Informing Policy with Evidence and AnalysisNessuna valutazione finora

- Guilty Until Proven Innocent: The Crisis in Our Justice SystemDa EverandGuilty Until Proven Innocent: The Crisis in Our Justice SystemNessuna valutazione finora

- Malcolm Gladwell BooksDocumento3 pagineMalcolm Gladwell BooksYounessElkarkouriNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Read PeopleDocumento93 pagineHow To Read PeopleJasminaNessuna valutazione finora

- Focusing Instruction ManualDocumento15 pagineFocusing Instruction Manualplan2222100% (1)

- Book ReviewDocumento23 pagineBook ReviewKartik MaheshwariNessuna valutazione finora

- RSD - Transformations Manual OCRDocumento44 pagineRSD - Transformations Manual OCRAnton Gabriel100% (1)

- Book Review PPT: BlinkDocumento12 pagineBook Review PPT: BlinkParnamoy DuttaNessuna valutazione finora

- Understanding Unconscious Intelligence and Intuition: "Documento20 pagineUnderstanding Unconscious Intelligence and Intuition: "Leti MouraNessuna valutazione finora

- Mental Mistakes - Whitney TilsonDocumento73 pagineMental Mistakes - Whitney TilsonDong-up SukNessuna valutazione finora

- The Prince of Tides-Study Guide Questions 2012Documento10 pagineThe Prince of Tides-Study Guide Questions 2012Ili AtallaNessuna valutazione finora

- What To SayDocumento157 pagineWhat To SayPaco De Alba100% (2)

- Tongue TwistersDocumento4 pagineTongue TwistersRoxana IrimieaNessuna valutazione finora

- Blink ReviewDocumento23 pagineBlink ReviewcurairoNessuna valutazione finora