Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Pictograph

Caricato da

Александр СеровTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Pictograph

Caricato da

Александр СеровCopyright:

Formati disponibili

The Pictographic Account Book

of an Ojibwa Fur Trader

GEORGE FULFORD

McMaster

University

This paper is about the pictographic account book of an Ojibwa fur trader

w h o m a n a g e d the American Traders' post at Vermillion Lake from 1835 to

1839. In thefirstsection I shall describe the account book and its provenience. In the next section, I will outline the history of the fur trade in the

Vermillion-Rainy Lake area. Following this, I shall provide a biography of

the trader. T h e n I will conduct a detailed analysis of the account book in

order to determine the profitability of the Vermillion Lake post. Finally, I

shall discuss what the account book reveals about the economics, politics

and social history of the fur trade in the Upper Great Lakes region during

the late 1830s.1

The Account Book

Vincent R o y managed the Vermillion Lake post from 1835 to 1839. His

account book is dated November 28, 1838 and is kept in the U.S. National

Anthropological Archives at the Smithsonian Insitution, Washington D.C.,

file number 4836. According to the accession card, the book was donated by

John M . Lawler of Wilbraham Massachussetts in 1963. It is leather bound

and in good condition, measuring 10 x 15.7 centimeters.

Many thanks to the National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C. for permission to publish material from Vincent Roy's

account book. Thanks also to the Library of Congress for permission to publish

material from the Schoolcraft Papers and to the Minnesota Historical Society for

permission to publish material from the Henry Mower Rice papers. Lee Guemple,

Valerie Grant, Trudy Nicks and Ted Stewart helped m e identify various items of

merchandise in Roy's account book while Ruth Fulford created the charts accompanying this article. Alex M c K a y assisted in the translation of Ojibwa names.

Tim Holzkammfirstdrew m y attention to the biography of Vincent Roy in the

Rice papers.

190

PICTOGRAPHIC A C C O U N T B O O K

191

Roy's account book contains 92 pages bearing pictographic inscriptions.

Three pages record Roy's year-end inventory of unsold merchandise and two

pages record his year-end inventory of furs. O n e page associated with the

inventory pages contains a record which I a m unable to identify while two

others itemize the retail price of merchandise R o y sold to his customers. T h e

remaining 84 pages record the individual accounts of 35 different Ojibwa

trappers, each of w h o m is identified by a pictographic signature. These

signatures have been reproduced in Chart 8. They typically appear in the

upper right corner of pages on the left side of the account book and usually depict h u m a n forms, occasionally with an associated family or clan

emblem. Twenty-three trappers are also identified by Ojibwa names, phonetically transcribed in longhand using R o m a n orthography (two of these

names are unintelligible). T h e handwriting resembles that found in a manuscript biography of Vincent R o y which is contained in the Papers of Henry

M o w e r Rice (1879). These papers are kept in the archives of the Minnesota

Historical Society.

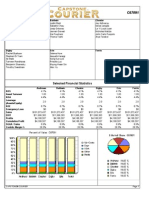

I have been able to identify 40 of the 48 different kinds of trade goods

appearing in Roy's account book and all 12 species of fur-bearing animals.

These items are indexed in Charts 2 A - D , found at the end of this paper. T h e

eight items of merchandise which I have not yet identified represent about

2 % of total sales and are identified as miscellaneous in Charts 3 and 7.

R o y recorded each of his customer's debits and credits on facing pages of

the account book. Pictographs representing trade goods (i.e., debits) appear

on the left hand pages, below a sign (usually a h u m a nfigure,family or clan

emblem) identifying the customer. Pictographs representing fur-bearing

animals (i.e., credits) appear on pages on the right side of the account book.

Charts 1 A - B appended to this paper illustrate the account of Shingwok

('Pine') as it appears in Roy's account book.

I have assumed that the trapper identified by R o y as Shingwok is, in

fact, Shingwokaunce ('Little Pine'). Shingwokaunce was a member of the

Crane clan and a famous Ojibwa war chief w h o fought with the English during the W a r of 1812. H e lived on the Garden River, near Sault Ste. Marie

and was alive at the time R o y managed the Vermillion Lake post. Three

other members of the Pine family (identified by pictographs of pine trees

placed above their heads) also appear in Roy's account book. They are W a a sawabikwan ('Shiny Medal'), Akiwenzie ('Old Man') and a trapper whose

n a m e is not phonetically transcribed but whose pictograph depicts rain or

snow falling from the sky. Despite the presence of Hudson's Bay C o m p a n y

and American Fur C o m p a n y posts within 75 kilometers of Garden River,

the Pines travelled more than 1,000 kilometers to Vermillion Lake. They

chose to go to Vermillion Lake for a variety of reasons. First, they were

attracted by the favourable terms of trade offered by the American Traders.

192

GEORGE FULFORD

T h e fact that Vincent Roy was himself half-Ojibwa m a y also have influenced

them. In addition, the Pines m a y have exhausted their credit at posts in the

vicinity of their home. A final factor was the policy of Henry Schoolcraft,

the U.S. Government Indian agent for the Michigan Territory. Schoolcraft

discouraged Americans from doing business with Ojibwas w h o maintained

allegiance with the British Crown. Canadian Ojibwas like the Pines therefore had to travel to remote posts outside Schoolcraft's jurisdiction if they

wished to cross-border shop.

Shingwokaunce's account (reproduced in Charts 1 A - B ) provides an important clue to understanding Vincent Roy's unusual system of numerical

notation. In the upper left hand corner of the left page are two entries:

49.00 D b . and 35.50 Cr. T h e reader will note that 48 full circles and two

half-circles appear on the left (debit) page while 35 full circles and one halfcircle appear on the right (credit) page. Whole circles therefore represent

$1 and half-circles 50 cent increments. Utilizing this information, I have

tabulated conventional balance sheets for each of Roy's customers. Appending the balance sheets for each of the 35 trappers w h o traded with Roy

in 1839 is clearly impractical. Instead, I have presented Shingwokaunce's

account as a specimen in Chart 1C. From the individual accounts such as

Shingwokaunce's I have compiled tables of Roy's total sales of merchandise

and purchases of furs. These tables appear in Charts 3-4. Debits in Roy's

account book refer to customer debits, while credits refer to customer credits. This suggests that Roy kept his account book mainly for the benefit

of his customers. Although Roy m a y have kept trading post accounts in a

more conventional format, I have been unable to find such accounts in the

National Anthropological Archives.

W a s Vincent Roy literate? Basic reading, writing and mathematical

skills would certainly have enabled him to deal effectively with suppliers

in St. Louis or N e w York. O n the other hand, procuring supplies could

have been efficiently handled by a regional manager in La Pointe or Fort

Snelling. As long as Roy could deliver furs on schedule and generate a

profit, he had no need for formal literacy and numeracy skills. Familiarity

with native pictographs would, however, have been indispensable in doing

business with Ojibwa trappers.

Evidence from Roy's account book suggests that he was illiterate. Names

and other incidental notation such as we find on Shingwokaunce's account

are inscribed in the same flowing cursive style found throughout the manuscript papers of Henry Rice. It is inconceivable that Roy wrote these papers.

O n the other hand, it is quite likely that Rice inscribed notes in the margins

of Roy's notebook. Rice would have routinely inspected the books after his

PICTOGRAPHIC A C C O U N T B O O K

193

employer Pierre Choteau acquired the Vermillion Lake post from the American Traders in the early 1840s H e must have inscribed the marginal notes

(perhaps while actually querying Roy) to help decipher the accounts.2

Further evidence of Roy's lack of formal literacy skills comes from his

use of pictographs to record inventory. If R o y was literate, then w h y would

he use the Ojibwa system in records that were only of use to him? T h e only

plausible explanation is that R o y was not skilled in European conventions of

literacy and numeracy. A s the son of a French trader living in the wilderness,

he did not have the opportunity to become literate. A s long as pictographic

records were used, both traders and trappers could decipher records of their

transactions. T h e pictographs R o y used at Vermillion Lake were familiar

to most of his Ojibwa contemporaries. For example, the symbols he used

to represent lynxs, bears and otters are similar to those used in Midewiwin

song scrolls. T h e symbol representingfishers,on the other hand, is clearly

derived from a popular Ojibwa origin myth concerning the so-called "fisher

stars" (Ursa major). 3

Pages from account books like Vincent Roy's are illustrated in Garrick

Mallery's famous monograph on American Indian picture writing (1893:Figures 175-180). Mallery says he obtained these accounts from unidentified

Abnaki traders in Maine in 1888. This fact is noteworthy, because it demonstrates h o w widespread the use of pictographs was a m o n g natives in the 19th

century.4

Rice was regional manager for the Choteau Company, which bought the Vermillion Lake post from the American Traders in the early 1840s. From 1847 to

1849 Roy and his eldest son were employed by Choteau to manage the Vermillion

Lake post.

For examples of bears and otters in Midewiwin song scrolls see Hoffman

(1891:Plate IXA). The famous lynx at Agawa Rock, reproduced in Dewdney and

Kidd (1967:85) is almost identical to the lynx pictographs in Vincent Roy's account book. For an account of thefisherstar story see Schoolcraft (1856:105-110)

and Jones (1917:197-203 and 1919:469-487). Each year, between the winter solstice and the spring equinox, the last four stars of thefisher'stail disappear below

the northern horizon. This explains the association of thefisher'stail with a star

in Roy's account book.

4

Pictographs depicting animals were widely used as sacred symbols by native

groups throughout the Northeastern Woodlands during prehistoric times (see, for

example: Winchell 1911; Dewdney and Kidd 1968; Vastokas and Vastokas 1973;

Swauger 1974; Lothson 1976). The sacred function of pictographs during the

historic period is documented by Schoolcraft (1851b), Hoffman (1891), Mallery

(1893), Densmore (1910), Dewdney (1975), Vennum (1978), Vecsey (1983) and

Vastokas (1984). However there has been little research on the secular use of

pictographs. Yet formal similarities in the pictographs depicting animals can be

found at rock art sites, in Midewiwin song scrolls and in the Vermillion Lake

account book. Such similarities suggest a link between the sacred and secular

functions of the animals depicted by pictographs. Animals which had sacred

194

GEORGE FULFORD

Despite their widespread distribution, the use of pictographs a m o n g

natives declined in the late 19th century. T h e opening of Presbyterian

mission schools in Michilimackinak (1823) and La Pointe (1830) promoted

the growth of both Christianity and literacy in the Upper Great Lakes

region.5 T h e spread of "the four Rs" (reading, writing, arithmetic and

religion) eventually changed the fur trade. T h e changes began when traders

like Vincent R o y sent their children to school. Vincent Jr. was 14 years old

when his father enrolled him in the La Pointe school in 1839. Although he

only attended school for two years, he acquired enough education to secure a

job as the manager of a store in La Pointe. Six years later Vincent Jr. joined

his father as account clerk at the Vermillion Lake post.

Schooling introduced Vincent Jr. to literacy, numeracy and a Calvinistic shrewdness in business. These were skills that his father lacked. As

long as frontier traders like Vincent Sr. accepted native religion and used

pictographs to keep their accounts, Ojibwa trappers could concentrate on

what they did best hunting and trapping. But once traders like Vincent Jr. took over, it was only a matter of time until Ojibwa trappers were

obliged to conform and convert in order to do business. This process of

assimilation did not happen overnight. It took at least two generations.

But once Ojibwas began sending their children to school, there there was

no turning back. B y the middle of the 20th century, indigenous forms of

religion, literacy and numeracy were all but lost in the Upper Lakes region.

History of the Vermillion Lake Post

According to oral tradition recorded by William Warren (1885:89-96) the

Ojibwa people did not inhabit the Upper Great Lakes region until the 15th

century. Historical evidence summarized by Conrad Heidenreich (1987:Plate

35) indicates that refugees of the Iroquois Wars such as the Mississauga,

Nipissing, Ottawa and Hurons fled from the Lower into the Upper Great

Lakes area at this time. Archaeological evidence suggests a fairly continuous

cultural horizon in the Upper Great Lakes region for the past 1,500 years

(Brose 1978; Dawson 1974; Wright 1972).

From the journals of early missionaries (Allouez 1896:53; Dablon 1896:

165-169, 191-195), traders (Perrot 1911:157-190; Grant 1960:346-369) and

explorers (Mackenzie 1927:62-78) it is known that the Vermillion and Rainy

Lake area was alternately occupied by Assiniboine, Cree, Sioux and Ojibwa

significance to prehistoric hunters had become mere commodities in the eyes of

traders and trappers by the mid-19th century. In the light of this dramatic change,

the Midewiwin can be seen as an Ojibwa-style cargo cult, marking a transitional

period when animals had both sacred and secular meaning.

discussions of the L a Poi

#IDSW

nte mission, see Moranian (1981) and Widder

( 1981).

PICTOGRAPHIC A C C O U N T B O O K

195

peoples throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. This is not surprising,

considering that the area lies between the drainage basins of Lake Superior]

Lake Winnipeg, James Bay and the Mississippi River. The area also borders'

three ecological zones: the boreal spruce forest, mixed forest parklands and

prairie grasslands. T h e prehistoric and early-historic inhabitants of the

Vermillion and Rainy Lake region thus had a rich selection of resources,

includingfish,wildfowl, moose, deer, elk, caribou, bison and a wide variety

of fur-bearing animals.

From about 1730 to 1756 the French operated forts and trading posts

on Lake of the W o o d s and Rainy Lake. M a p s of this period show an Ojibwa

village on Vermillion Lake (Tanner 1987:40^11). With the collapse of the

French fur trade after the Seven Years War, the Northwest C o m p a n y established trading posts on or near the sites of the old French forts. In addition,

the Hudson Bay C o m p a n y established a post to compete with the Northwest C o m p a n y post on Rainy Lake (Tanner 1987:98-99). Competition for

furs wasfierce,leading to near-depletion of the beaver by the time the two

companies consolidated in 1821. Shortly after consolidation, the Hudson's

Bay C o m p a n y eliminated the old Northwest C o m p a n y posts at Lake of the

W o o d s and Rainy Lake, thus obtaining a monopoly in the area and temporarily relieving pressure on the beaver. This situation was shortlived,

however. B y 1830 the American Traders had established a post at Rainy

Lake, on the site of the old Northwest C o m p a n y post. In addition, the

American Traders established the post at Vermillion Lake. It was at this

post that Vincent R o y was employed in 1839.

Biography of Vincent Roy (based on the Henry Mower Rice Papers)

Vincent Roy was born at Leech Lake, Minnesota in 1797. He was the son

of a French-Canadian trader of the same name. W h e n Roy was about 18

years old his family emigrated to Fort Francis, where he worked as a trader

for the Northwest Company. In 1821, when the Northwest and Hudson's

Bay Companies merged, he worked for the new company for another 12 to

15 years. During this time he married Lisette Lacombe, a w o m a n of French

and Ojibwa ancestry. T h e couple had theirfirstson (Vincent Jr.) in 1825.

In the mid-1830s R o y joined the American Traders and managed their

post at Vermillion Lake until 1840. During this time he wintered at Vermillion Lake, buying goods in Mackinaw and selling them to the Bois Fortes

bands of Ojibwas on Rainy Lake and Vermillion Lake. In 1840 Roy left

Vermillion Lake. For the next eight years he managed the American Fur

Company's post at Leech Lake. From 1847 to 1849 Roy returned to Vermillion Lake, where he worked for Pierre Choteau, w h o had bought the post

from the American Traders. At this time Vincent Jr. was employed by his

father as the post bookkeeper.

196

GEORGE FULFORD

In 1850 Vincent Roy Sr. returned to the American Fur C o m p a n y for one

year. Then he moved to Red Lake, where for the next 10 years he worked

as a trader for Peter E. Bradshaw. From 1861 to 1864 Vincent Sr. acted as

Bradshaw's agent at Lake Nipigon. Then he returned to Vermillion Lake,

where managed the trading post until 1869, when he contracted a severe

illness and moved to Superior City (near Fond du Lac) to live with Vincent

Jr. He died on 18 February 1872.

Like his father, Vincent Jr. was a trader for most of his life. From

1839 to 1841 he attended the mission school at La Pointe. Afterwards

he managed a store in La Pointe for six years. From 1847 to 1849 he

worked as a bookkeeper for his father at Vermillion Lake. From 1850 to

1852 Vincent Jr. worked for his father's employer, Peter Bradshaw. During

those years he managed trading posts at Sandy Lake and Fond du Lac.

In 1852 he was employed briefly by the United States Government as an

interpreter. Afterwards he moved to Superior City, where he became general

manager for Alexander Paul. Paul operated trading posts on Red Lake,

Lake Winnibigoshish, Rainy Lake and Vermillion Lake. Each winter he

sent Vincent Jr. to these posts to do the bookkeeping, drop off supplies and

merchandise and pick up furs. W h e n Paul sold his posts to Bradshaw in

1860, Vincent Jr. continued to manage the interior posts. In 1866 Vincent

Jr. purchased several of these posts from Bradshaw, including the one at

Vermillion Lake.

Analysis of the Account Book

As a general rule, Indian trappers visited trading posts twice a year, once

in the late fall and once in the early spring. This pattern fit in with the

Ojibwa's traditional pattern of resource scheduling, which was described in

detail by Alexander Henry (1809). Henry spent a year living with an Ojibwa

hunter named Wawatam. During the winter W a w a t a m and his family shared

a hunting territory with a several other families at the headwaters of the A u

Sable River, on the western half of the Michigan peninsula. While there,

they hunted elk and bear and trapped beaver and otter. Just before spring

breakup the band travelled 110 kilometers downriver to the place where

the A u Sable River empties into Lake Michigan. For a month other bands

who had wintered in hunting territories adjacent to the various tributaries

of the A u Sable River congregated at the estuary to collect maple sap and

produce sugar. Then, after breakup, families canoed north to their summer

fishing camps on St. Martin Island. Along the way, W a w a t a m stopped at

Fort Michilimackinac to exchange furs for European trade goods. O n the

way back to the A u Sable River in the early fall, W a w a t a m probably made

a second stop at the fort to obtain winter supplies. Then he and his family

returned to the mouth of the A u Sable River, where they hunted elk, deer,

PICTOGRAPHIC A C C O U N T B O O K

197

bear and trapped beaver and marten until freeze-up. After freeze-up they

returned to their winter camp.

Faunal analysis of numerous archaeological sites in the Saginaw Valley,

on the east side of the Michigan peninsula, indicates that the pattern of

resource scheduling followed by W a w a t a m dates back to late Archaic times

(Keene 1981:190-195). This pattern was also followed by Ojibwas living in

the boreal forest to the north (Dawson 1983:79-80).

Dated November 28, 1839, Roy's account book appears to contain only

the records of Indians making the late fall visit to the Vermillion Lake trading post. This is indicated by the fact that Roy's fur-inventory is nearly

twice as large as the tally of furs obtained from adding up individual accounts. T h e difference between the tally of furs obtained from adding up

individual accounts and the year-end inventory must therefore represent his

spring receipts.

R o y used the same pictographic system in both his individual accounts

and year-end inventory. In both cases he identified fur-bearing animals

using the pictographs illustrated in Chart 2D. H e indicated the quantity

of each type of fur using straight vertical lines just like those appearing in

Shingwokaunce's account. T o simplify the representation of large numbers

he used the the R o m a n numeral X to indicate units often. Circles represent

dollars and an X surrounded by a circle represents $10.00.

R o y lists 920 muskrat skins worth $190.00 in his fur-inventory. A single

muskrat skin was thus worth an average of 20.7 cents.6 Unfortunately, Roy

does not provide retail values for other types of pelts. T o obtain these,

Ifirstcalculated the wholesale (i.e., purchase) prices of furs by averaging

figures from individual accounts. Based on these accounts, Roy bought

665 muskrat skins, for which he paid $75.10. A single muskrat skin thus

cost R o y an average of 11.3 cents. Roy's markup on muskrats, obtained by

subtracting the purchase price from the selling price and then dividing the

result by the purchase price, was 8 3 % . Assuming the same markup on all

types of pelts, I have multiplied the purchase price of each type of pelt by

1.83 (i.e., cost plus m a r k u p ) to derive the selling price. These figures are

summarized Chart 4.7

6

This tallies well with Henry Schoolcraft's 1826 "Tariff of Indian Goods",

reproduced in Chart 3. According to Schoolcraft, American Fur Company traders

paid Indian trappers 11 cents each for muskrat skins, which they could then sell

for 20 to 30 cents each in the N e w York.

7

Minor inaccuracies are introduced in Chart 4 due to the process of rounding

markup, average purchase price and average selling price. For example, in Chart

4 the purchase price of muskrat skins (based on Roy's year-end inventory) is listed

as $103.83. Thisfigurewas derived by dividing the selling price by 1.83. Yet it

is $2.63 more than thefigurederived by multiplying the total number of muskrat

skins by their average selling price.

198

GEORGE FULFORD

Interpreting Roy's year-end inventory of merchandise is problematic.

One reason for this is that Roy does not clearly and consistently indicate

units of weight or volume. This makes deciphering recorded quantities of

shot, gunpowder, beads and flour impossible. Another complication arises

from Roy's use of an inverted V in his inventory of thread, blankets and

cloth. Does this unit represent a linear measure in feet or yards? On the

other hand, perhaps the symbol represents a standard number of units such

as one dozen. Or perhaps it represents something else. There is no way of

knowing just what the inverted V represents. A final source of confusion

in Roy's merchandise inventory comes from double entries. In cases where

double entries appear, do we subtract the larger from the smaller entry, or

add the two together?

Roy's inconsistencies in record-keeping have made it impossible to provide a total dollar value for the year-end inventory of unsold merchandise

presented in Chart 7. It is, nevertheless, possible to make some general r'

statements and inferences based on the unambiguous entries in this chart.

First, it is clear that Roy overestimated what his sales of hunting supplies

would be. At year-end, he still had 3 muskets, 77 knives, 30 snares and

30 leg hold traps. From these figures we can .conclude either that Roy's

customers obtained these items from another source or that they did not

require them as much as they had formerly. As Chart 6 shows, Roy undercut the American Fur Company's prices for merchandise and offered more

for furs. It therefore seems unlikely that Roy was losing customers to other

traders. Rather, it appears that overall demand for hunting supplies had

fallen.

Why would trappers no longer require the tools of their trade? One

reason for this is connected to Roy's low returns of beaver skins and also

to his low year-end stock of cheap blankets and cloth. 8 The reason why

trappers no longer required as many hunting supplies was that key fur and

game resources were nearly depleted in the Upper Great Lakes region at

this time. Based on his analysis of records from the Hudson's Bay Company

post at Osnaburgh House, Charles Bishop (1974:11) has shown that by 1821

beaver, moose and caribou were becoming rare among the Northern Ojibwa.

"Indians were forced to pursue small game, fish and hare, to offset the

growing threat of starvation", according to Bishop (1974:12). Bishop also

notes that Ojibwas came to rely more and more on British and Americanmade snares, traps and cloth. 9

8

Roy's year-end inventory of 3.0 point blankets is indicated by four and a half

inverted Vs while his inventory of 2.5 point blankets is indicated by 13 of these

Vs. His inventory of cloth is indicated by four large vertical lines and seven dots.

9

Since Osnaburgh house is 700 kilometers north of Vermillion Lake, one may

ask whether a comparison with Vermillion Lake is warranted. Such a comparison

I

t

j

r

t

t

f

t

f

PICTOGRAPHIC A C C O U N T B O O K

199

Roy's inventory of furs and merchandise supports Bishop's theory that

depletion of g a m e and fur resources led Ojibwas to rely on manufactured

goods from the trading posts. Only 37 beaver were brought to the Vermillion

Lake post in 1839, compared to 920 muskrats and 615 rabbits. Lynx, bears,

wolves and foxes were n o w the mainstay of the fur trade at Vermillion

Lake, together accounting for 7 2 % of the total value of furs. Because these

species did not rely on beaver, moose or caribou for food, they continued

to proliferate in the Upper Great Lakes region.

Alexander Mackenzie's remarks (see note 9) indicate that moose and

caribou populations in the Vermillion and Rainy Lake area had been in

decline since the late 18th century. Vincent Roy must have been aware of

this situation. So w h y did he miscalculate his stock of hunting supplies and

blankets in 1839? T w o events shed light on this matter. First, a smallpox

epidemic ravaged Ojibwas in the Upper Great Lakes region between 1837

and 1838 (Tanner 1987:173-174). This epidemic would have reduced both

the number of trappers and the returns of those trappers w h o survived.

Second, thousands of Ojibwas from the Michigan and Wisconsin territories were displaced into western Minnesota at this time. This population

movement resulted from treaties negotiated by the U.S. Government between 1833 and 1837 (Kappler 1904:402-462; Moranian 1981:243; Tanner

1987:155-161). It had an immediate impact on the fur trade. Traplines

languished in the vacated territories, while in Minnesota the population of

fur-bearing animals was subject to excessive pressure. T h e short-term result

was a reduction both in the return of furs and in sales of merchandise. In

the long term conservation measures partially restored populations of furbearers and market prices adjusted to the changes in supply. In the short

term, however, d e m a n d for manufactured goods continued to grow among

Ojibwas in the Upper Great Lakes region and trappers found it increasingly

difficult to pay for these items with furs. B y the late 19th century m a n y

Ojibwas were therefore leaving their traplines to search for more lucrative

sources of income in towns and cities.

is supported by the fact that Bishop's observations echo those of the explorer

Alexander Mackenzie, who passed through the Vermillion and Rainy Lake region in 1789. According to Mackenzie (1801:63), the region was rich infishand

wild rice. In the bush, however, game was particularly scarce. "Some fatal circumstance had destroyed the game", he wrote. This situation promoted Ojibwa

dependency on European trade goods. According to the factor of the Hudson's

Bay Company post on Rainy Lake (cited in Ray 1974:147), caribou and moose

were so scarce in 1826 that he was "obliged to bring in drest leather & parchement

to supply [natives] with the means of making [their] shoes & snowshoes."

200

GEORGE FULFORD

The Economic Impact of the Fur Trade on Ojibwas

Fur returns at the Vermillion Lake post reveal m u c h about the demography and ecology of the Upper Great Lakes. But Roy's account book also

provides clues about the economic impact of the fur trade on Ojibwas. A s

Chart 3 shows, by 1839 Ojibwa trappers had replaced traditional toolkits with American firearms, leg hold traps, snares, knives, axes and hide

scrapers. Other manufactured goods were gaining in popularity as well.

Ojibwa w o m e n were substituting cloth and blankets for moose and caribou

hide. Stitching woollen cloth required implements and techniques that were

different from traditional hide stitching. Iron needles thus replaced bone

needles and awls, while thread replaced sinew, twisted bark and hair. T h e

nature of clothing decoration also changed, with colourful glass beads replacing dyed porcupine quills and moose hair. B y 1839 Ojibwa w o m e n relied

almost completely on American or British-made textiles to m a k e clothing.

This is clearly revealed in Chart 3, where the sales of the cloth, blankets

and millinery supplies are twice that of hunting supplies.

Ojibwa w o m e n also seem to have preferred American-made domestic

supplies to their own. A s Roy's account book shows, iron pots were a

popular item of trade in 1839, replacing traditional Ojibwa birch bark and

clay containers. Iron frying pans were also popular, their use introducing a

new means of cooking meat which had the advantage of being m u c h faster

than roasting. Along with the new cooking implements came new foods.

Tea and bannock (made from lard andflour)were not staples in 1839, but

they were becoming increasingly significant in the Ojibwa diet. Tobacco

and alcohol are absent from Roy's inventory of trade goods, but m a y have

been presented as gifts when trappers arrived at the Vermillion Lake post.10

As Ojibwa w o m e n became consumers of manufactured goods, they became active in the fur trade as well. At least two w o m e n the unnamed

wife of Biidaanakwod ('Approaching Cloud') and Midwegan giishigokwe

('Sky D r u m W o m a n ' ) had their o w n accounts in 1839. Each w o m a n bought

a blanket and a small quantity of cloth. Biidaanakwod's wife also bought

a knife, while Midwegan giishigokwe bought a hide scraper, thread, a pipe

and a leg hold trap. Whereas Biidaanakwod paid for his wife's purchases,

Midwegan giishigokwe paid with her o w n lynx, mink, otter and wolf pelts.

Based strictly on h o w m u c h she purchased, Midwegan giishigokwe was

not one of Roy's most valued customers. For $17.00 of merchandise she

In Canada traders could sell alcohol to the Indians. In the U.S., however,

federal statutes prohibited this trade. Although large fines could be levied on

offenders, the U.S. statutes were rarely enforced. O n e reason for this is that fur

traders argued that they could not compete with British traders if they were not

allowed to sell alcohol. Another reason is the failure of states and territories to

recognize federal government jurisdiction (Prucha 1962:102-38).

PICTOGRAPHIC A C C O U N T B O O K

201

traded furs worth $21.50 (wholesale). This transaction brought Roy a gross

profit of approximately $18.00. Significantly, Midwegan giishogokwe bought

only what she needed and did not go into debt. In fact, she established a

credit of $3.50 with Roy.

Based on h o w m u c h they purchased, Biidaanakwod and his wife were

m u c h more valued customers than Midwegan giishigokwe. They purchased

$123.50 worth of merchandise, yet they traded only $52.50 worth of furs,

accumulating a debt of $71.00. O n Biidaanakwod's account Roy m a d e a

gross profit (calculated strictly on the basis of his markup on furs and

merchandise) of $93.57. Yet more than two-thirds of this money was tied

up in Biidaanakwod's debt.

Based on what Biidaanakwod and his wife purchased from Roy, it would

appear that they were serious about repaying their debt. More than half

their purchases were of hunting supplies, including a musket, a sizable quantity of shot and powder and 11 leg hold traps. Biidaanakwod and his wife

had fallen on hard times during in the winter of 1839, but clearly they

hoped that their fortunes would improve. O n the other hand, their taste for

American consumer goods had also contributed to their debt. A m o n g their

1839 purchases were a pistol (of dubious value in hunting), 2 clay pipes and

a pair of earrings.

A customer identified only by the pictographic signature of a m a n wearing a top hat is the clearest example of a trapper whose taste for consumer

goods exceeded his ability to pay for them. O n $65.50 worth of furs, this

customer ran up a debt of $131.90. Significantly, he did not buy any leg

hold traps, guns, powder, hide scrapers or axes. H e did, however, buy a

large quantity of cloth, needles and thread, 2 pairs of scissors, 3 blankets,

a pair of breeches, 4 combs, 11 clay pipes, 7 tomahawk pipes and 1 earring

(not a pair). R o y m a d e a gross profit of $188.59 from his transactions with

the m a n in the top hat, but 7 0 % of this money was tied up in his customer's

debt.

Niish O d e h i m ('Two Hearts') is thefinaltrapper w h o m I shall discuss in

this section. O n $359.10 worth of furs, Niish Odehim bought $319.00 of merchandise, establishing a credit of $40.10 with Roy. O n these transactions,

Roy's gross profit was $512.97. Included in Niish Odehim's purchases are 2

muskets, a sizable quantity of powder, shot and gunflints, 5 hide scrapers,

7 snares and 4 leg hold traps. H e also bought a large quantity of needles,

thread and cloth, as well as 21 blankets, 6 clay pipes, a mirror, comb and

pair of earrings.11

" T h e size of Niish Odehim's purchases suggest that he was the chief of a small

band. If we assume that Niish Odehim procured goods solely for the members of

his band rather than secondary trading, then we can deduce the size of the band

based on his purchases. The purchase of 21 blankets suggests that approximately

202

GEORGE FULFORD

Averages from Roy's individual accounts reveal that the typical Ojibwa

trapper visiting Vermillion Lake in 1839 did not resemble any of the customers discussed so far. T h e typical trapper brought the pelts of 1 beaver,

2 otters, 20 muskrats, 5 minks, 4 martens, 1fisher,3 foxes, 2 wolves, 9

lynxs and 12 rabbits, for which he received $50.00. With this m o n e y the

trapper bought a few pounds of powder and shot, a new knife, axe, hide

scraper,file,pipe, a skein of snare wire and 3 leg hold traps. For his wife

he bought a sack offlour,some tea, a hide scraper, pot, some glass beads,

a few yards of cloth to m a k e leggings and new blankets for each m e m b e r of

his family. Every 3 years or so the trapper would buy himself a new gun.

T o procure these simple items the trapper would incur an annual debt of

approximately $20 (i.e., the value of a new gun and a three-point blanket).

This debt represented about 40 percent of the trapper's income and would

be paid in part by his annual annuity from the U.S. Government.

Even after the decline of the beaver, Vermillion Lake remained profitable. Roy's account book reveals that in 1839 Ojibwas were able to continue buying American manufactured goods by selectively trapping predatory fur-bearers. Declining moose and caribou populations insured a steady

demand a m o n g Ojibwas for cloth and blankets. Figures from Henry Schoolcraft's 1826 Tariff (reproduced in Chart 5) show that traders working for the

American Fur C o m p a n y marked up merchandise 4 0 0 % and furs 100-200%.

O n the other hand, Roy marked up merchandise 6 8 % and furs 8 3 % (see

Charts 4-7). Unfortunately, Roy does not provide a year-end statement of

merchandise sales. Chart 3, based on Roy's individual accounts, shows that

he sold $2,115.90 worth of trade goods to Ojibwa trappers. But it is likely

that these accounts record only fall sales. Roy's annual sales could therefore be twice the amount recorded in Chart 3. Based strictly on fall sales,

the wholesale cost of merchandise sold to trappers is obtained by dividing

$2,115.90 (total retail sales) by 1.68, (average cost plus markup). Gross

profit is obtained by subtracting $1,259.46 (wholesale cost) from $2,115.90

(total retail sales), yielding afigureof $856.44.

Based on his year-end inventory, the gross gross profit on Roy's sale

of furs to N e w York was $3,526.21. I derived this amount from Chart

4 by subtracting $4,248.45 (what Roy paid trappers for their furs) from

$7,774.66 (what Roy's furs would have fetched in N e w York). Roy's gross

profit on sales of both merchandise and furs was $4,382.65. Subtracting

the outstanding credit of $426.80 that Roy extended to his customers yields

a total of S3.955.85. It is not possible to determine exactly h o w much

of the trappers' debt was written off with by their annuity payments and

how much Roy carried as bad debt. Nor is it possible to determine bad

this number of people were in the band. The purchase of 6 clay pipes sugges

that 6 adults were in the band.

PICTOGRAPHIC A C C O U N T B O O K

203

debts incurred from Roy's N e w York buyers. Finally, it is not possible to

accurately determine h o w m u c h inventory Roy had left at year's end (see

Chart 7). Even if w e assume that R o y wrote off all of the credit that

he extended to trappers, incurred a similar bad debt from his N e w York

agents, was left with $200.00 of unsold merchandise at year's end, spent

$200 maintaining the post and paid himself a $500 salary, his net profit

would have been $2,629.05. This represents a 1 0 9 % return on the $1259.46

invested in merchandise. If w e assume that spring sales of merchandise

equalled fall sales and factor the resulting gross profit into our estimate

of net profit, then the Vermillion Lake post would have generated a 1 7 7 %

return on investment.

Even in a bad year like 1839 it was possible to run the Vermillion Lake

post at a healthy profit. Ironically, conscientous trappers like Biidaanakwod

w h o wished to write off their debts risked overharvesting local fur resources.

M a n y of the trappers perhaps even Biidaanakwod himself were being

displaced from their traditional traplines and hunting territories to make

room for white settlers. Other trappers like the nameless m a n in the top hat

m a y have stopped trapping altogether. The m a n in the top hat depended

on credit for his supplies. T o maintain his credit, he traded tomahawk

pipes and woollen clothes sewn by his wife for furs. But because he was

trading luxury goods bought from the post at retail prices for furs that

he could only sell to the post for wholesale prices, the m a n in the top hat

was operating at a loss. A s a result, he sank further and further into debt.

Traders tolerated his transactions because they inflated the retail value of

their o w n merchandise.

Unlike m a n y of Roy's other customers, Niish Odehim and Midwegan

giishigokwe were able to stay out of debt. Midwegan giishigokwe accomplished this by limiting her consumption of consumer goods. Perhaps her

trapline was not productive, or perhaps she chose not to overharvest the

animals. For whatever reasons, Midwegan giishigokwe did not fall into the

trap of buying more than she could afford. Her purchases from Roy were

modest and suggest that she lived alone and had no dependents.

B y pooling his resources with other members of his band, Niish Odehim

was able to afford some luxuries. T h e strategy of sharing worked well as

long as traplines and hunting territories remained productive. The risk was

that trappers' demand for British and American manufactured goods would

encourage them to overharvest and eventually deplete local populations of

fur-bearing animals. This pattern had already emerged in the Upper Great

Lakes region as early as the 1780s and would continue to be a threat as

long as trappers like Biidaanakwod and the unnamed m a n in the top hat

continued going into debt. Traders fueled this situation by extending unreasonable levels of credit to their customers. They did this to maintain

204

GEORGE FULFORD

their highly-profitable sales of merchandise to trappers. Credit stimulated

trappers' demand for merchandise at a time when their fur returns were

low. It was a short-term solution to the long-term problem of making the

fur trade ecologically, culturally andfinanciallyviable. In the end, credit

only contributed to the problem.

The Political and Social Impact of the Fur Trade on Ojibwas

In this section I shall outline what Vincent Roy's account book reveals about

the fur trade's impact on traditional Ojibwa political structure, social structure and world view. Vincent R o y does not provide any commentary or

other direct evidence pertaining to these matters. However, through analysis and interpretation of the names and pictographic signatures recorded in

his account book, some insights can be gained.12

T h e pictographic signatures and phonetically-transcribed names appended to Roy's accounts and reproduced in Chart 8 identify trappers on

the basis of one or two distinct personal features. Both the signatures and

the names often describe the same features. For example, the pictographic

signature of Niish Odehim ('Two Hearts') depicts a m a n with two hearts.

T h e n a m e suggests a m a n with a strong but divided heart, a m a n w h o is

capable of both shrewdness and generosity. Another trapper identified as

Gitigewinini ('Farmer') is depicted holding a scythe. Waabodjig ('White

Fisher') is represented by the drawing of afisherwhile Ajijaakaunce ('Little

Crane') is represented by the drawing of a m a n standing next to a crane.

Shingwokaunce ('Little Pine') is shown as a m a n with a pine tree rising

above his head. Signatures with pine trees also belong to Akiwensi ('Old

Man') and a m a n whose n a m e was not transcribed. These m e n , like Shingwokaunce, were probably also members of the Pine family.

It is likely that the plants, trees, birds and animals represented in

the signatures and phonetically-transcribed names of Shingwokaunce, Ajijaakaunce, Waabodjig and others represent clan or family emblems (sometimes refered to as totems). William Warren (1885:44-45) lists 21 Ojibwa

clan emblems or totems which can be divided into three groups corresponding to the particular element to which they are distinctively adapted (i.e.,

air, earth and water). These are: (1) birds, including eagle, hawk, crane,

goose, black duck, loon and gull; (2) terrestrial animals and reptiles, including moose, caribou, bear, wolf, lynx, beaver, marten and rattlesnake;

l2

The distinction between long and short vowels and lenis and fortis consonants

was ignored by the person w h o transcribed the trappers' names in Roy's account

book. In this text and accompanying charts I have retranscribed these names

in a manner which clearly recognizes these important distinctions. In matters

of orthography I have been guided by Nichols and Nyholm (1979) and Rhodes

(1985).

PICTOGRAPHIC A C C O U N T B O O K

205

(3)fish,including pike, catfish, sucker, sturgeon and whitefish). A final

clan the m e r m a n defies simple categorization, but probably should be

included in the water group.

While extensive, Warren's list is certainly not exhaustive. John Tanner

(1956:314-315) lists three additional clans (pickerel, sparrow hawk and water snake) while Henry Schoolcraft (1851a:248, 253, 290) notes the names

of m a n y additional Ojibwa families not mentioned by Warren but recorded

in Roy's account book. These include those of Shingwokaunce, Akiwenzie

and Waabodjig.

T h e exact relationship of family and clan names is somewhat problematic. According to Frances Densmore (1929:52-53) there are various

classes of Ojibwa names, including birth names, names acquired as a result of dreams or visions, nicknames and clan names. While an individual

had only one birth n a m e or clan name, they might have any number of

dream names or nicknames. Unlike other classes of names, clan names were

generally reserved only for chiefs.

It is difficult to distinguish birth names and dream names from clan

names in Chart 8. It is noteworthy, however, that most of the intelligibly

transcribed names in the chart refer, either directly or indirectly, to air,

earth or water elements, thus linking the person named not only to their

clan, but also to the natural environment. This pattern suggests that the

Ojibwa trappers whose names were recorded in Roy's account book continued to perceive themselves as part of, rather than masters over nature.

There is no w a y of proving that the names and signatures reproduced

in Chart 8 necessarily refer to Ojibwa clans. In fact, the existence of such

clans is the subject of a scholarly debate which hinges on differing interpretations of the same ethnohistorical and ethnographic data. S o m e scholars

(Ritzenthaler 1978:753; Rogers 1978:763; Rogers and Taylor 1981:236) suggest that groups inhabiting the southern portion of the Ojibwa culture area

were traditionally organized into clans, while groups to the north were not.

T h e presence of clans suggests a somewhat greater level of social complexity

a m o n g Southern Ojibwas, but the reasons for this remain obscure. Hickerson (1962:30-35) believes that, unlike their northern neighbours, Southern

Ojibwas inhabited sedentary villages year-round. H e argues that such villages were adapted to a richer resource base in the south and were a feature

of precontact Southern Ojibwa society. Rogers (1978:763), on the other

hand, states that Southern Ojibwas only settled in sedentary villages during the historic period. Prior to this time, clans and villages m a y not have

been a feature of Southern Ojibwa society. Callender (1978:620) and Bishop

(1989:56-58) point to the fact that Southern Ojibwas could have developed

clans without necessarily living in sedentary villages. They argue that clans

were important in promoting peaceful coexistence and trade between groups

206

GEORGE FULFORD

from neighbouring hunting andfishingterritories, but do not explain w h y

Northern Ojibwas lack such social structures.

By focusing on social structure, I believe that scholars have tended to

ignore the traditional world view of Ojibwas. This world view stresses the

identification of h u m a n names with the names of plants and animals. A s

Levi- Strauss (1966:142) has pointed out, natural relationships formed the

foundation upon which Ojibwa personal and collective identity was traditionally built. Clan emblems, he suggests, functioned as category markers

which had both natural and social significance. According to him, Ojibwas

symbolically divided thefish,quadrupeds or birds functioning as clan emblems into parts, which they then restructured into personal names. Parallel

to the way in which certain species of animals symbolized separate Ojibwa

communities, the parts of these animals were symbolically incorporated in

personal names. In this w a y names such as M a k w a bimide ('Bear Grease')

and Gasha nonshgan ('Sharp Claws') were identified with the bear, while

Gichi binesi ('Big Bird') and Ni migizim ('My eagle') were identified with

the eagle.

Not all of the names recorded by Royfitneatly into the scheme suggested by Levi-Strauss. T h e use of the diminutive suffix -aunce in names

like Ajijaakaunce, Shingwokaunce and Ogaunaunce signifies the son of the

patriarch denoted by the stem. T h e prefixing of waaba 'white' in the names

W a a b a ma'ingan ('White W o l f ) and Waabodjig ('White Fisher') evokes the

archetypal qualities of brightness and light associated with the clan animal.

In names such as Shingwokaunce ('Little Pine') and Waabodjig ('White

Fisher') the association with clan animals was all but lost (the former was

a member of the Crane clan while the latter was a m e m b e r of the Caribou

clan). T h e tendency for chiefly names to diverge from the n a m e of the clan

animal suggests that particularly strong individuals could forge identities

that eclipsed even their clan.

According to Warren (1885:42-43) the clan n a m e and emblem functioned like a surname and descended patrilineally. M e m b e r s of the same

clan called themselves brother or sister and did not intermarry. Both Warren and Tanner assert that clan emblems are unique to Ojibwas. "Thus",

Tanner writes (1956:314), "those bands of Ojibbeways w h o border on the

country of the Dahcotah, or Sioux, always understand thefigureof a m a n

without totem, to mean one of that people."

Ojibwas used clan emblems (what Tanner calls "totems") as a form of

signature on grave posts, on rocks and trees to mark their presence to fellow travellers, and in birch bark records of dreams (Schoolcraft 1851b:351;

see also Plates 49, 50 and 55). It is thus not surprising to find Roy using such symbols to identify the Ojibwa trappers with w h o m he traded in

1839. Yet symbols of plants, trees, birds and animals are represented in

PICTOGRAPHIC A C C O U N T B O O K

207

only five of the 35 signatures recorded in Roy's account book. Associations with family and clan emblems are suggested, however, in seven of

the 21 names that are intelligibly transcribed. These names are: Ogaunaunce ('Little Pickerel'), M a k w a bimide ('Bear Grease') Gichi binesi ('Big

Bird'), Gaagaage naabe ('Raven'), Gasha nonshgan ('Sharp Claws'), Ni

migizim ('My eagle') and W a a b a ma'iingan ('White Wolf). In addition,

the names of Biidaanakwod ('Approaching Cloud'), Midwegan giishigokwe

('Sky D r u m W o m a n ' ) and W a a b a giishig ('Clear Sky') all refer to the sky,

and thus indirectly to bird clans. O n the other hand, the names of Biweosse

('Walking Around') and Gitigewinini ('Farmer') seem to refer to earth (i.e.,

terrestrial animal) clans. Like Gitigewinini, the n a m e of Gasha manoomin

('Rice Cutter') seems to refer to a distinctive occupation. A s a clan designation, Gasha m a n o o m i n m a y refer to either earth or water clans (wild rice

grows in shallow lakes). Finally, the signatures of Mashkodewense ('Ash

Man'), Midewegan Giishigokwe ('Sky D r u m W o m a n ' ) and three other trappers whose names are either unintelligible or not transcribed are all depicted

with blackened faces, suggesting a c o m m o n but unstated affiliation.

O f the 35 different pictographic signatures that are recorded in Roy's

account book, 13 (37%) lack any reference to family or clan emblems. If,

however, the sample is restricted to the 21 signatures which also have intelligibly transcribed names accompanying them, then only two Niish

O d e h i m ('Two Hearts') and Nind akooz (T a m tall') lack such reference. These cases, representing only 1 0 % of the sample of signatures with

intelligibly transcribed names, are nicknames refering to unique personal

characteristics of the n a m e d person.

A m o n g Ojibwas exchange was traditionally controlled by band chiefs.

I therefore assume that most of the signatures recorded in Roy's account

book belonged to chiefs. According to Bishop, regional exchange networks

in exotic goods were already well-developed a m o n g Ojibwas before contact

with Europeans. Such goods included copper, chert, lead, red ochre, woven

mats, nets, pottery, shell money, hides and pelts. Concerning this trade,

Bishop writes (1986:40):

Among protohistoric Algonquians, such links helped to maintain alliances

and provided information and favors in time of need. The symbolic and

sociopolitical value of goods m a y often have been more important than the

ostensible primary purpose. This may have remained true for a short time

after European goods entered the system. As the historic fur trade expanded

and grew in importance, however, and as furs came to be the chief medium

of exchange, the commodity value of items quickly came to dominate.

The presence of French and later British and American trading posts

undoubtedly undermined traditional Ojibwa trading networks, as well as

the sociopolitical structures which they supported. Chiefs of bands w h o

208

GEORGE FULFORD

controlled access to key trading posts or prime fur resources often became

influential trading chiefs. At the same time, the trading post assumed a

growing importance in the Ojibwas' seasonal scheduling activities, replacing

the s u m m e r village as a gathering place. A s this happened, profit-oriented

exchange gradually replaced traditional gift-giving. In addition, the economic importance of commercial hunting and trapping grew while the economic importance of traditional subsistence activities diminished. Ojibwas'

respectful attitude towards animals as "other-than-human persons" (Hallowell 1963:274) slowly gave way to an attitude that animals were natural

resources to be exploited.

In precontact times trade functioned to preserve Ojibwa sociopolitical

structures. T h e trading of furs for European and American manufactured

goods m a y initially have reinforced these structures as well as materially

benefitting Ojibwas. In the long term, however, it undermined traditional

Ojibwa society and promoted economic dependency. B y the early 19th century the fur trade was pulling Ojibwas away from their traditional band and

tribal exchange systems and integrating them into the mercantile economy

of colonial North America. This economy, based as it was on the extraction

of resources from native land, ultimately expanded at the expense of native

people such as Ojibwas.

T h e fur trade introduced European and American manufactured goods

into Ojibwa society. This new wealth had a profound and lasting effect

on Ojibwa social structure. A s Bishop (1974:139) has shown, early traders

recognized the status of traditional Ojibwa leaders by bestowing them with

special gifts. "The band leaders", he writes,

. . . were accorded preferential treatment, receiving gifts at the beginning and

conclusion of trading transactions. T h e suit of clothing which was given to

them before trade began was called the 'Captain's Outfit,' and as this term

suggests it served to m a k e the trading captains stand out from the rest of the

Indians.

Early European traders recognized the authority of traditional Ojibwa

chiefs by making them trading captains. However, Bishop (1974:139-140)

points out traders also used the new symbols of authority to manipulate the

chiefs.

. . . if a band failed to obtain a sufficient quantity of furs or provisions to pay

off its debts, the band leader was denied these symbols of office. O n the other

hand ... if they were successful in persuading their followers to trap and

bring their furs to the appropriate c o m p a n y posts, the band leaders received

their uniforms as well as an additional present at the conclusion of trade the

amount of which was proportional to the n u m b e r of Indians they had brought

with them.

PICTOGRAPHIC A C C O U N T B O O K

209

Vincent Roy's account book records the accounts of at least four trading captains. Their status is indicated by the ceremonial regalia depicted

in their pictographic signatures. O n e chief, identified as Gasha nonshkan

('Sharp Claws'), is shown wearing a military-style uniform, complete with

epaulettes. Waasawabigwan ('Shiny Medal') and two other chiefs whose

names were not phonetically transcribed are also depicted wearing large

medals around their necks. Significantly, none of these chiefs is identified

by the presence of family or clan emblems.

Evidence from Roy's account book suggests that clan chiefs had already

lost m u c h of their prestige and authority by the 1830s. Only one of the 35

trappers w h o traded at Vermillion Lake in 1839 appended an identifiable

clan e m b l e m to his signature. This was Ajijaakaunce ('Little Crane') of the

Crane clan. Ajijaakaunce was one of Roy's more successful trappers, yet he

did not identify himself as a trading captain. In 1839 he exchanged $100.50

of furs for $98.00 of merchandise. His purchases included six blankets and 3

clay pipes, suggesting that there were at least 3 adults and 3 children in his

band. This size of band is optimally suited to trapping, small-game hunting

andfishing.Bishop (1974:4-16) notes that single-family bands of this type

evolved during the 18th century after the decline of moose and caribou

populations in the Upper Great Lakes region. Before this time, when big

g a m e was more plentiful, Ojibwa bands normally consisted of three or more

hunters and their families.

Bishop suggests that the reduction in band size fostered the development of a concept of individual ownership of hunting territories a m o n g

Ojibwas.13 Unfortunately, there is no w a y to either prove or disprove this

claim on the basis of evidence from Roy's accounts. However, the fact that

Ajijaakaunce identified himself with the Crane clan, but lived in a singlefamily band, does suggest that Ojibwa society had already fragmented by

1839. But it is important to remember that Ajijaakaunce's purchases probably only reflect the composition of his winter hunting band. W h a t was

happening in Ajijaakaunce's s u m m e r village is another matter.

Traditionally, Ojibwas congregated in semi-permanent villages during

the s u m m e r . These villages were often located at the narrows of large rivers

or lakes, where spawning fish could be easily speared or netted. Early

trading posts were often located near these s u m m e r villages and m a y have

attracted even more native people to the s u m m e r villages than in the precontact period. However, with rival companies competing for furs during

13

The issue of the development of a concept of private property among Algonquian groups like Ojibwas is a subject of considerable scholarly debate. For a

fuller discussion see Speck (1915), Cooper (1939), Leacock (1954), Rogers (1963,

1986), Bishop (1974, 1986), Ray (1974), Morantz (1986), Sieciechowicz (1986) and

Tanner (1986).

210

GEORGE FULFORD

the late 18th and early 19th centuries and the subsequent decline of the

beaver, caribou and moose populations, Ojibwas travelled to trading posts

that were further afield. In this way they obtained the most favourable

terms of trade and credit available.

From their analysis of ethnohistorical records, Grant (1983:77) and

Rogers and Rogers (1983:93) have determined that during the 19th century members of the Crane clan occupied a region at the headwaters of

the Severn River. Cranes also inhabited parts of the north shore of Lake

Superior. This is documented by Schoolcraft (1851a:110), w h o identifies

Shingwokaunce as a m e m b e r of the Crane clan living in the vicinity of Sault

Ste. Marie. In addition, John Tanner (1956:79) records that in the 1790s

an Ojibwa named W a a b a ajijaak ('White Crane') lived on the Mouse River,

near Lake Winnipeg.

Whether coming from the north, east or west, Ajijaakaunce probably

travelled for m a n y days and possibly weeks to get from his s u m m e r fishing

village to the trading post at Vermillion Lake. Other trappers w h o travelled

long distances to trade at Vermillion Lake included Shingwokaunce, W a a bodjig and Gasha manoomin. 14 Such travelling reduced the time trappers

could spend with fellow family and clan members at their s u m m e r villages

and ultimately had a negative impact on the social cohesion of Ojibwa clans.

By the mid-19th century the fur trade appears to have fragmented

both Ojibwa s u m m e r fishing villages and winter hunting camps. At the

same time it undermined the influence of traditional leaders. Ajijaakaunce,

Shingwokaunce, Waabodjig and Gasha manoomin m a y have retained their

symbolic importance as chiefs, but their relatively modest demand for merchandise from the trading post at Vermillion Lake shows that, unlike their

grandfathers, they no longer controlled the distribution of wealth.

Schoolcraft does not mention Ajijaakaunce in any of his writings. Concerning

Shingwokaunce he writes (1851a:110) that he was a member of the Crane clan who

lived on the British side of the St. Mary's River. "He had a tuft of beard on his

chin, wore a hat, and had some other traits in his dress and gear which smacked

of civilization." More information about Shinwokaunce is provided in J.G. Kohl's

account of his travels on Lake Superior (1860:373-384). About Gasha Monoomin,

Schoolcraft (1851a:290) says only that he lived on Post Lake, near Green Bay. O n

the other hand, Schoolcraft (1848:134-145) wrote extensively about a chief named

Waabodjig who died in 1793 and was probably the father or grandfather of the

trapper of the same name identified by Vincent Roy. According to Schoolcraft,

Waabodjig Sr. was a member of the Caribou clan, lived in Zaaggamogong ('Place

sticking out of the water', today known as La Pointe, Wisconsin) and was famous for his exploits against the Sioux. With other inhabitants of Zaaggamogong

village, he shared a winter hunting territory that "extended along the southern

shores of Lake Superior from the Montreal River, to the inlet of the Misacoda, or

Burntwood River of Fond du Lac."

PICTOGRAPHIC A C C O U N T B O O K

211

Like clan chiefs, trading captains had lost m u c h of their authority by

the 1830s. Despite the grandiose images conveyed in their pictographic

signatures, the four trading captains w h o came to Vermillion Lake in 1839

had already lost m u c h of their political influence. M a n y trading posts that

had flourished during the late 18th and early 19th centuries were closed

d o w n after the consolidation of the Northwest and Hudson's Bay C o m p a n y

in 1821. Chiefs w h o had controlled access to posts that were closed d o w n

lost their geopolitical advantages. B y trading with and extending credit to

individual hunters, British and American traders further undermined the

authority and prestige of trading captains. In addition, the overharvesting

of fur-bearing animals had taken its toll. Instead of bringing hundreds of

pelts to the trading post each spring and fall, as they had done formerly,

trading captains had only a few dozen pelts each to trade in 1839.15 A s a

result of all of these factors, political authority shifted from trading chiefs to

individual trappers. Combined with this, the change from big to small-game

hunting led to the fragmentation of Ojibwa bands. T h e relocation of Ojibwas

from the Michigan peninsula to Minnesota following the U.S. Government

treaties of the 1830s contributed to the further breakdown of traditional

Ojibwa socioeconomic and political structures.

T h e declining fortune of trading captains is indicated by four trends

emerging from information in Vincent Roy's account book. First, the type

and quantity of furs exchanged by trading captains does not stand out

from those of other Ojibwa trappers. Second, trading captains procured

the same type and quantity of trade goods as other trappers. The typical trapper visiting Vermillion Lake in 1839 traded furs worth $50.00 for

merchandise worth $70.00. Compare this to the trading captains. Gasha

nonshgan traded $72.50 worth of furs for $107.50 worth of merchandise.

Waasawabigwan exchanged $32.00 of furs for $50.00 of merchandise. O n e

of the two trading chiefs whose names were not phonetically transcribed in

Roy's account book traded $51.00 of furs for $63.00 of merchandise. T h e

other exchanged $8.00 of furs for twofiles,two blankets and a small quantity of cloth worth a total of $21.00. Compare these modest exchanges with

that of a successful trapper like Niish Odehim, w h o exchanged $359.10 of

"Alexander Henry (1901:139, 147) records that in the winter of 1764 he trapped

one "hundred beaver-skins, sixty racoon-skins and six otter, of the total value

of about one hundred and sixty dollars." This amount does not include what

W a w a t a m (who was not a trading captain) and the seven members of his family

trapped. Henry also mentions that during February of the same winter Wawatam's

family killed an undisclosed number of elk, together yielding "four thousand

[pounds] weight of dried venison." Much of this meat was stored in caches for

future use. According to Quimby (1962:232) this amount of meat was enough to

meet the nutritional needs of Wawatam's family for approximately seven months.

212

GEORGE FULFORD

furs for $319.00 of merchandise. Niish O d e h i m did not identify himself as a

trading captain.

A third indication that trading captains had lost m u c h of their authority

and prestige emerges from the fact that they were all in debt. Patterns of

consumption which they could afford during the late 18th and early 19th

centuries could only by sustained by credit in 1839. Trapping new species of

fur-bearing animals such as lynxs, wolves, foxes and bears helped trappers

improve their returns of furs. But traders did not always profit as m u c h

from the sale of these species as they did with the beaver. Consequently,

they increased markups on merchandise which they sold to trappers in order

to maintain high levels of profit. T o stay out of debt, trappers had to reduce

their purchases from trading posts. But trading captains, w h o depended on

gift-giving and conspicuous displays of wealth to maintain their status, were

unable to do this.

The final indication that trading captains had lost power comes from

the fact that none of those identified in Roy's account book indicated their

family or clan emblem in their pictographic signatures. T h e absence of

such emblems suggests that the trading captain's uniform had become the

preeminent symbol of authority for chiefs, replacing clan animals such as

the eagle, bear and crane. This, in turn, indicates that trading captains

were identifying more strongly with new European and American forms of

wealth than with the animals, which were Ojibwas' traditional source of

wealth. But by the 1830s fur returns were so meager that few traders were

prepared to provide their trappers with captain's outfits. Those trappers

w h o had previously earned these symbols of authority found it increasingly

difficult to secure the wealth necessary to sustain their prestige.

Conclusion

By the 1830s the fur trade had eroded traditional Ojibwa economic, social

and political structures. Multi-family winter bands which had been adapted

to big g a m e hunting were fragmenting in order to adapt to new ecological

conditions following the depletion of moose and caribou. T h e importance of

s u m m e rfishingvillages was being usurped by the trading post. Clans were

declining in importance and the authority of m a n y clan chiefs had already

been usurped by trading captains. Trading captains themselves were losing

prestige and authority as a result of the shifting fortunes of the fur trade.

By 1839 the beaver was practically trapped out in the Upper Great

Lakes region. Traders like Vincent R o y were relying increasingly on sales

of merchandise to generate profits. Trappers were exchanging other furbearing species for manufactured goods. M a n y trappers relied on credit

and were going into debt.

PICTOGRAPHIC A C C O U N T B O O K

213

Ojibwas were becoming increasingly acculturated in the 19th century.

T h e proliferation of mission schools and growth of the four Rs (reading,

writing, arithmetic and religion) promoted the development of European

values at the expense of Ojibwa values. But in 1839 this process was still

in its infancy. Ojibwas continued to use traditional names and think of

themselves as living in harmony with the natural world.

REFERENCES

Allouez, Father Claude

1896- Of the Mission to the Nadouesiouek. Pp. 53-55 in The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents, 54. Reuben Gold Thwaites, ed. Cleveland: Burrows. [1667.]

Bishop, Charles A.

1974

The Northern Ojibwa and the Fur Trade. Toronto: Holt, Rinehart

and Winston.

1986

Territoriality A m o n g Northeastern Algonquians. Anthropologica 28:

37-63.

1989

The Question of Ojibwa Clans. Pp. 43-61 in Actes du vingtieeme

congrees des algonquinistes. William Cowan, ed. Ottawa: Carleton

University.

Brose, David S.

1978

Late Prehistory of the Upper Great Lakes Area. Pp. 569-582 in

Handbook of North American Indians, 15. Bruce G. Trigger, ed.

Washington: Smithsonian Institution.

Callender, Charles

1978

Great Lakes-Riverine Sociopolitical Organization. Pp. 610-621 in

Handbook of North American Indians, 15. Bruce G. Trigger, ed.

Washington: Smithsonian Institution.

Cooper, John M .

1939

Is the Algonquian Family Hunting Ground System Pre-Columbian?

American Anthropologist 54:66-90.

Dablon, Father Claude

1896- Of the Peoples Connected with the Mission of Saint Esprit. Pp. 165169 in The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents, 54. Reuben

G. Thwaites, ed. Cleveland: Burrows.

Dawson, K.C.A.

1974

The McCluskey Site. National Museum of Man, Mercury Series.

Archaeological Survey of Canada Paper No. 25. Ottawa: National

Museums of Canada.

Densmore, Frances

1910

Chippewa Music. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 45. Washington.

1929

Chippewa Customs. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 86.

Washington.

214

G E O R G E FULFORD

Dewdney, Selwyn

1975

The Sacred Scrolls of the Southern Ojibway. Toronto: University of

Toronto Press.

Dewdney, Selwyn, and Kenneth Kidd

1967

Indian Rock Paintings of the Great Lakes. 2nd Edition. Toronto:

University of Toronto Press.

Grant, Peter

1960

The Sauteux Indians. Reprinted in Les Bourgeois de la Compagnie

du Nord-Ouest, 2. New York: Antiquarian Press. [1804.]

Grant, Valerie

1983

The Crane and Sucker Indians of Sandy Lake. Pp. 75-90 in Actes

du quatorzieme congres des algonquinistes. William Cowan, ed. Ottawa: Carleton University.

Hallowell, A. Irving

1963

Ojibwa World View and Disease. Pp. 258-315 in Man's Image in

Medicine and Anthropology. Iago Goldstein, ed. New York: International Universities Press.

Heidenreich, Conrad E.

1987

The Great Lakes Basin, 1600-1653. Pp. 94-95 in Historical Atlas

of Canada, 1. R. Cole Harris, ed. Toronto: University of Toronto

Press.

Henry, Alexander

1901

Travels and Adventures in Canada and the Indian Territories between the Years 1760 and 1766. James Bain, ed. Boston. [1809.]

Hickerson, Harold

1962

The Southwestern Chippewa: An Ethnohistorical Study. The American Anthropological Association, Memoir 92. Menasha, Wisconsin.

Hoffman, W.J.

1891

The Mide'wiwin or "Grand Medicine Society" of the Ojibwa. Pp. 143300 in Bureau of American Ethnology, Seventh Annual Report. Washington.

Jones, William

1917

Ojibwa Texts, 1. Truman Michelson, ed. Leyden: E.J. Brill.

1919 Ojibwa Texts, 2. Truman Michelson, ed. Leyden: E.J. Brill.

Kappler, Charles J., ed.

1904

Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties, 2. Washington.

Kohl, Johann Georg

I860

Kitchi-Gomi. Trans. Lascelles Wraxall. London: Chapman and

Hall.

Leacock, Eleanor

1954

The Montagnais "Hunting Territory" and the Fur Trade. American

Anthropological Association, Memoir 78. Menasha, Wisconsin.

Lvi-Strauss, Claude

1966

The Savage Mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

PICTOGRAPHIC A C C O U N T B O O K

215

Lothson, Gordon Allan

1976

The Jeffers Petroglyphs Site. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society.

Mackenzie, Alexander

1927

Voyages. John W . Garvin, ed. Toronto: Radison Society. [1801.]

Mallery, Garrick

1893

Picture-Writing of the American Indians. Pp. 3-822 in Bureau of

American Ethnology, Tenth Annual Report. Washington.

Marquette, Father Jacques

1896- Letter to the Reverend Father Superior of the Missions. Pp. 16994 in The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents, 54. Reuben G.

Thwaites, ed. Cleveland: Burrows.

Moranian, Suzanne Elizabeth

1981

Ethnocide in the Schoolhouse. Wisconsin Magazine of History 64:

243-260.

Morantz, Toby

1986

Historical Perspectives on Family Hunting Territories in Eastern

James Bay. Anthropologica 28:64-91.

Nichols, John, and Earl Nyholm

1979

Ojibwewi-ikidowinan: An Ojibwe Word Resource Book. Saint Paul:

Minnesota Archaeological Society.

Perrot, Nicolas

1911

Memoire. Originally edited by Jules Tailhan and published in Paris,

1864. Translated by E m m a Helen Blair and reprinted in The Indian

Tribes of the Upper Mississippi Valley and Region of the Great Lake

Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark. [1710.]

Prucha, Francis Paul

1962

American Indian Policy in the Formative Years. Cambridge, Mass.:

Harvard University Press.

Quimby, George I.

1962

A Year with a Chippewa Family, 1763-1764. Ethnohistory 9(3):217239.

Ray, Arthur J.

1974

Indians in the Fur Trade. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Rhodes, Richard A.

1985