Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

GR No. 17654 (2016)

Caricato da

Alexis Anne P. ArejolaDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

GR No. 17654 (2016)

Caricato da

Alexis Anne P. ArejolaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

--

CEHTTIF:_~E':: ::~~'.U:E COPY

.":::"""i\c"

">

II'

fl

.....

fl

"'"

..

WILFRE=..0 , .

\ , ...'N

~~<t-

~

~public of tbe Jbilippine~

~upreme

l~

Division ~~':d..:. of Court

T;;inJ Di:vi~Ion

QI:ourt

FEB l 7 2016

;flllanila

THIRD DIVISION

DEPARTMENT OF AGRARIAN

REFORM, QUEZON CITY &

PABLO MENDOZA,

Petitioners,

- versus -

G.R. NO. 176549

Present:

VELASCO, JR., J., Chairperson

PERALTA,

PEREZ,*

REYES, and

JARDELEZA, JJ.

ROMEO C. CARRIEDO,

Respondent.

Promulgated:

x--------------------------------------------~-~--x

DECISION

JARDELEZA, J.:

This is a Petition for Review on Certiorari' assailing the Court of

Appeals Decision dated October 5, 2006 2 and Resolution dated January l 0,

2007 3 in CA-G.R. SP No. 88935. The Decision and Resolution reversed the

Order dated February 22, 2005 4 issued by the D~partment of Agrarian

Reform-Central Office (DAR-CO) in Administrative Case No. A-9999-03CV-008-03 which directed that a 5.0001 hectare piece of agricultural land

(land) be placed under the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program

pursuant to Republic Act (RA) No. 6657 or the Comprehensive Agrarian

Reform Law.

Designated as Regular Member of the Third Division per Special Order No. 2311 elated January

14, 2016.

Rollo, pp. 14-22.

Penned by Associate Justice Jose L. Sabio Jr. with Associate Justices Regalado E. Maambong and

Ramon M. Bato, Jr. concurring, id. at 164-179.

Penned by Associate Justice Jose L. Sabio Jr. with Associate Justices Regalado E. Maambong and

Ramon M. Bato, Jr. concurring,jd. at 28-29.

CA mllo, pp. 56-61,

Decision

G.R. No. 176549

The Facts

The land originally formed part of the agricultural land covered by

Transfer Certificate of Title (TCT) No. 17680,5 which in turn, formed part of

the total of 73.3157 hectares of agricultural land owned by Roman De Jesus

(Roman).6

On May 23, 1972, petitioner Pablo Mendoza (Mendoza) became the

tenant of the land by virtue of a Contrato King Pamamuisan7 executed

between him and Roman. Pursuant to the Contrato, Mendoza has been

paying twenty-five (25) piculs of sugar every crop year as lease rental to

Roman. It was later changed to Two Thousand Pesos (P2, 000.00) per crop

year, the land being no longer devoted to sugarcane.8

On November 7, 1979, Roman died leaving the entire 73.3157

hectares to his surviving wife Alberta Constales (Alberta), and their two

sons Mario De Jesus (Mario) and Antonio De Jesus (Antonio).9 On August

23, 1984, Antonio executed a Deed of Extrajudicial Succession with Waiver

of Right10 which made Alberta and Mario co-owners in equal proportion of

the agricultural land left by Roman.11

On June 26, 1986, Mario sold12 approximately 70.4788 hectares to

respondent Romeo C. Carriedo (Carriedo), covered by the following titles

and tax declarations, to wit:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

TCT No. 35055

(Tax Declaration) TD No. 48354

TCT No. 17681

TCT No. 56897

TCT No. 17680

The area sold to Carriedo included the land tenanted by Mendoza

(forming part of the area covered by TCT No. 17680). Mendoza alleged that

the sale took place without his knowledge and consent.

In June of 1990, Carriedo sold all of these landholdings to the

Peoples Livelihood Foundation, Inc. (PLFI) represented by its president,

Bernabe Buscayno.13 All the lands, except that covered by TCT No. 17680,

were subjected to Voluntary Land Transfer/Direct Payment Scheme and

were awarded to agrarian reform beneficiaries in 1997.14

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

Comprising a total of 12.1065 hectares. DAR-CO Records, pp. 537-539.

CA rollo, p. 57.

Id. at 73-74.

Rollo, p. 165.

Id. at 166.

Id.; DAR-CO Records (A-9999-03-CV-008-03), pp. 500-503.

Rollo, p. 166.

CA rollo, pp. 75-78.

DAR-CO Records (A-9999-03-CV-008-03), pp. 493-495.

Id. at 571-572; rollo, p. 166.

Decision

G.R. No. 176549

The parties to this case were involved in three cases concerning the

land, to wit:

The Ejectment Case

(DARAB Case No. 163-T-90 | CAG.R. SP No. 44521 | G.R. No.

143416)

On October 1, 1990, Carriedo filed a Complaint for Ejectment and

Collection of Unpaid Rentals against Mendoza before the Provincial

Agrarian Reform Adjudication Board (PARAD) of Tarlac docketed as

DARAB Case No. 163-T-90. He subsequently filed an Amended Complaint

on October 30, 1990.15

In a Decision dated June 4, 1992,16 the PARAD ruled that Mendoza

had knowledge of the sale, hence, he could not deny the fact nor assail the

validity of the conveyance. Mendoza violated Section 2 of Presidential

Decree (PD) No. 816,17 Section 50 of RA No. 119918 and Section 36 of RA

15

16

17

18

CA rollo, pp. 69-72.

Id. at 62-75.

Providing That Tenant-farmers/Agricultural Lessees Shall Pay the Leasehold Rentals When They

Fall Due and Providing Penalties Therefor (1975). Section 2 of PD No. 816 reads:

Section 2. That any agricultural lessee of a rice or corn land under Presidential

Decree No. 27 who deliberately refuses and/or continues to refuse to pay the rentals

or amortization payments when they fall due for a period of two (2) years shall, upon

hearing and final judgment, forfeit the Certificate of Land Transfer issued in his

favor, if his farmholding is already covered by such Certificate of Land Transfer, and

his farmholding.

Agricultural Tenancy Act of the Philippines. Section 50 of RA No. 1199 reads:

Section 50. Causes for the Dispossession of a Tenant. Any of the following shall

be a sufficient cause for the dispossession of a tenant from his holdings:

(a) The bona fide intention of the landholder to cultivate the land

himself personally or through the employment of farm machinery

and implements: Provided, however, That should the landholder not

cultivate the land himself or should fail to employ mechanical farm

implements for a period of one year after the dispossession of the

tenant, it shall be presumed that he acted in bad faith and the land

and damages for any loss incurred by him because of said

dispossession: Provided, further, That the land-holder shall, at least

one year but not more than two years prior to the date of his petition

to dispossess the tenant under this subsection, file notice with the

court and shall inform the tenant in wiring in a language or dialect

known to the latter of his intention to cultivate the land himself,

either personally or through the employment of mechanical

implements, together with a certification of the Secretary of

Agriculture and Natural Resources that the land is suited for

mechanization: Provided, further, That the dispossessed tenant and

the members of his immediate household shall be preferred in the

employment of necessary laborers under the new set-up.

(b) When the current tenant violates or fails to comply with any of

the terms and conditions of the contract or any of the provisions of

this Act: Provided, however, That this subsection shall not apply

when the tenant has substantially complied with the contract or with

the provisions of this Act.

(c) The tenant's failure to pay the agreed rental or to deliver the

landholder's share: Provided, however, That this shall not apply when

the tenant's failure is caused by a fortuitous event or force majeure.

(d) When the tenant uses the land for a purpose other than that

specified by agreement of the parties.

Decision

G.R. No. 176549

No. 3844,19 and thus, the PARAD declared the leasehold contract

terminated, and ordered Mendoza to vacate the premises.20

Mendoza filed an appeal with the Department of Agrarian Reform

Adjudication Board (DARAB). In a Decision dated February 8, 1996,21 the

DARAB affirmed the PARAD Decision in toto. The DARAB ruled that

ownership of the land belongs to Carriedo. That the deed of sale was

unregistered did not affect Carriedos title to the land. By virtue of his

ownership, Carriedo was subrogated to the rights and obligation of the

19

20

21

(e) When a share-tenant fails to follow those proven farm practices

which will contribute towards the proper care of the land and

increased agricultural production.

(f) When the tenant through negligence permits serious injury to the

land which will impair its productive capacity.

(g) Conviction by a competent court of a tenant or any member of his

immediate family or farm household of a crime against the

landholder or a member of his immediate family.

Agricultural Land Reform Code. Section 36 of RA No. 3844 reads:

Section 36. Possession of Landholding; Exceptions. Notwithstanding any

agreement as to the period or future surrender, of the land, an agricultural lessee shall

continue in the enjoyment and possession of his landholding except when his

dispossession has been authorized by the Court in a judgment that is final and

executory if after due hearing it is shown that:

(1) The agricultural lessor-owner or a member of his immediate

family will personally cultivate the landholding or will convert the

landholding, if suitably located, into residential, factory, hospital or

school site or other useful non-agricultural purposes: Provided; That

the agricultural lessee shall be entitled to disturbance compensation

equivalent to five years rental on his landholding in addition to his

rights under Sections twenty-five and thirty-four, except when the

land owned and leased by the agricultural lessor, is not more than

five hectares, in which case instead of disturbance compensation the

lessee may be entitled to an advanced notice of at least one

agricultural year before ejectment proceedings are filed against him:

Provided, further, That should the landholder not cultivate the land

himself for three years or fail to substantially carry out such

conversion within one year after the dispossession of the tenant, it

shall be presumed that he acted in bad faith and the tenant shall have

the right to demand possession of the land and recover damages for

any loss incurred by him because of said dispossessions.

(2) The agricultural lessee failed to substantially comply with any of

the terms and conditions of the contract or any of the provisions of

this Code unless his failure is caused by fortuitous event or force

majeure;

(3) The agricultural lessee planted crops or used the landholding for a

purpose other than what had been previously agreed upon;

(4) The agricultural lessee failed to adopt proven farm practices as

determined under paragraph 3 of Section twenty-nine;

(5) The land or other substantial permanent improvement thereon is

substantially damaged or destroyed or has unreasonably deteriorated

through the fault or negligence of the agricultural lessee;

(6) The agricultural lessee does not pay the lease rental when it falls

due: Provided, That if the non-payment of the rental shall be due to

crop failure to the extent of seventy-five per centum as a result of a

fortuitous event, the non-payment shall not be a ground for

dispossession, although the obligation to pay the rental due that

particular crop is not thereby extinguished; or

(7) The lessee employed a sub-lessee on his landholding in violation

of the terms of paragraph 2 of Section twenty-seven.

Rollo, p. 75.

Id. at 76-83.

Decision

G.R. No. 176549

former landowner, Roman.22

Mendoza then filed a Petition for Review with the Court of Appeals

(CA). The case was docketed as CA-G.R. SP No. 44521. In a Decision dated

September 7, 1998,23 the CA affirmed the DARAB decision in toto. The CA

ruled that Mendozas reliance on Section 6 of RA No. 6657 as ground to

nullify the sale between De Jesus and Carriedo was misplaced, the section

being limited to retention limits. It reiterated that registration was not a

condition for the validity of the contract of sale between the parties.24

Mendozas Motions for Reconsideration and New Trial were subsequently

denied.25

Mendoza thus filed a Petition for Review on Certiorari with this

Court, docketed as G.R. No. 143416. In a Resolution dated August 9, 2000,26

this Court denied the petition for failure to comply with the requirements

under Rule 45 of the Rules of Court. An Entry of Judgment was issued on

October 25, 2000.27 In effect, the Decision of the CA was affirmed, and the

following issues were settled with finality:

1) Carriedo is the absolute owner of the five (5) hectare land;

2) Mendoza had knowledge of the sale between Carriedo and Mario

De Jesus, hence he is bound by the sale; and

3) Due to his failure and refusal to pay the lease rentals, the tenancy

relationship between Carriedo and Mendoza had been terminated.

Meanwhile, on October 5, 1999, the landholding covered by TCT No.

17680 with an area of 12.1065 hectares was divided into sub-lots. 7.1065

hectares was transferred to Bernabe Buscayno et al. through a Deed of

Transfer28 under PD No. 27.29 Eventually, TCT No. 17680 was partially

cancelled, and in lieu thereof, emancipation patents (EPs) were issued to

Bernabe, Rod and Juanito, all surnamed Buscayno. These lots were

identified as Lots C, D and E covered by TCT Nos. 44384 to 44386 issued

on September 10, 1999.30 Lots A and B, consisting of approximately 5.0001

hectares and which is the land being occupied by Mendoza, were registered

in the name of Carriedo and covered by TCT No. 34428131 and TCT No.

344282.32

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

Id. at 79-80.

Id. at 89-95.

Id. at 92-93.

CA rollo, p. 113.

Rollo, pp. 96-97.

Id. at 98.

DAR-CO Records (A-9999-03-CV-008-03), pp. 451-452.

Decreeing the Emancipation of Tenants from the Bondage of the Soil, Transferring to Them the

Ownership of the Land They Till and Providing the Instruments and Mechanism Therefor (1972).

DAR-CO Records (A-9999-03-CV-008-03), pp. 553-555.

Id. at 511.

Id. at 510.

Decision

G.R. No. 176549

The Redemption Case

(DARAB III-T-1476-97 | CA-G.R. SP

No. 88936)

On July 21, 1997, Mendoza filed a Petition for Redemption33 with the

PARAD. In an Order dated January 15, 2001,34 the PARAD dismissed his

petition on the grounds of litis pendentia and lack of the required

certification against forum-shopping. It dismissed the petition so that the

pending appeal of DARAB Case No. 163-T-90 (the ejectment case discussed

above) with the CA can run its full course, since its outcome partakes of a

prejudicial question determinative of the tenability of Mendozas right to

redeem the land under tenancy.35

Mendoza appealed to the DARAB which reversed the PARAD Order

in a Decision dated November 12, 2003.36 The DARAB granted Mendoza

redemption rights over the land. It ruled that at the time Carriedo filed his

complaint for ejectment on October 1, 1990, he was no longer the owner of

the land, having sold the land to PLFI in June of 1990. Hence, the cause of

action pertains to PLFI and not to him.37 It also ruled that Mendoza was not

notified of the sale of the land to Carriedo and of the latters subsequent sale

of it to PLFI. The absence of the mandatory requirement of notice did not

stop the running of the 180 day-period within which Mendoza could exercise

his right of redemption.38 Carriedos Motion for Reconsideration was

subsequently denied.39

Carriedo filed a Petition for Review with the CA. In a Decision dated

December 29, 2006,40 the CA reversed the DARAB Decision. It ruled that

Carriedos ownership of the land had been conclusively established and even

affirmed by this Court. Mendoza was not able to substantiate his claim that

Carriedo was no longer the owner of the land at the time the latter filed his

complaint for ejectment. It held that the DARAB erred when it ruled that

Mendoza was not guilty of forum-shopping.41 Mendoza did not appeal the

decision of the CA.

The Coverage Case

(ADM Case No. A-9999-03-CV-00803 | CA-G.R. SP No. 88935)

On February 26, 2002, Mendoza, his daughter Corazon Mendoza

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

Rollo, pp. 84-87.

Id. at 99-104.

Id. at 101.

Id. at 105-116.

Id. at 112-113.

Id. at 113-114.

Id. at 121.

Penned by Associate Justice Aurora Santiago-Lagman with Associate Justices Juan Q. Enriquez,

Jr. and Normandie B. Pizarro concurring, id.. at 118-127.

Id. at 123-126.

Decision

G.R. No. 176549

(Corazon) and Orlando Gomez (Orlando) filed a Petition for Coverage42 of

the land under RA No. 6657. They claimed that they had been in physical

and material possession of the land as tenants since 1956, and made the land

productive.43 They prayed (1) that an order be issued placing the land under

Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program (CARP); and (2) that the DAR,

the Provincial Agrarian Reform Officer (PARO) and the Municipal Agrarian

Reform Officer (MARO) of Tarlac City be ordered to proceed with the

acquisition and distribution of the land in their favor.44 The petition was

granted by the Regional Director (RD) in an Order dated October 2, 2002,45

the dispositive portion of which reads:

WHEREFORE, foregoing premises considered, the

petition for coverage under CARP filed by Pablo Mendoza,

et al[.], is given due course. Accordingly, the MARO and

PARO are hereby directed to place within the ambit of RA

6657 the landholding registered in the name of Romeo

Carriedo covered and embraced by TCT Nos. 334281 and

334282, with an aggregate area of 45,000 and 5,001 square

meters, respectively, and to distribute the same to qualified

farmer-beneficiaries.

SO ORDERED.46

On October 23, 2002, Carriedo filed a Protest with Motion to

Reconsider the Order dated October 2, 2002 and to Lift Coverage47 on the

ground that he was denied his constitutional right to due process. He alleged

that he was not notified of the filing of the Petition for Coverage, and

became aware of the same only upon receipt of the challenged Order.

On October 24, 2002, Carriedo received a copy of a Notice of

Coverage dated October 21, 200248 from MARO Maximo E. Santiago

informing him that the land had been placed under the coverage of the

CARP.49 On December 16, 2002, the RD denied Carriedos protest in an

Order dated December 5, 2002.50 Carriedo filed an appeal to the DAR-CO.

In an Order dated February 22, 2005,51 the DAR-CO, through

Secretary Rene C. Villa, affirmed the Order of the RD granting coverage.

The DAR-CO ruled that Carriedo was no longer allowed to retain the land

due to his violation of the provisions of RA No. 6657. His act of disposing

his agricultural landholdings was tantamount to the exercise of his retention

right, or an act amounting to a valid waiver of such right in accordance with

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

CA rollo, pp. 127-130.

Id. at 128.

Id. at 130.

Id. at 48-51.

Id. at 50.

Id. at 150-170.

Id. at 171.

Id. at 26.

Id. at 27, 52-54.

Id. at 56-61.

Decision

G.R. No. 176549

applicable laws and jurisprudence.52 However, it did not rule whether

Mendoza was qualified to be a farmer-beneficiary of the land. The

dispositive portion of the Order reads:

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the instant

appeal is hereby DISMISSED for lack of merit.

Consequently, the Order dated 2 October 2002 of the

Regional Director of DAR III, is hereby AFFIRMED.

SO ORDERED.53

Carriedo filed a Petition for Review54 with the CA assailing the DARCO Order. The appeal was docketed as CA-G.R. SP No. 88935. In a

Decision dated October 5, 2006, the CA reversed the DAR-CO, and declared

the land as Carriedos retained area. The CA ruled that the right of retention

is a constitutionally-guaranteed right, subject to certain qualifications

specified by the legislature.55 It serves to mitigate the effects of compulsory

land acquisition by balancing the rights of the landowner and the tenant by

implementing the doctrine that social justice was not meant to perpetrate an

injustice against the landowner.56 It held that Carriedo did not commit any of

the acts which would constitute waiver of his retention rights found under

Section 6 of DAR Administrative Order No. 02, S.2003.57 The dispositive

portion of the Decision reads:

WHEREFORE, premises considered and pursuant to

applicable law and jurisprudence on the matter, the present

Petition is hereby GRANTED. Accordingly, the assailed

Order of the Department of Agrarian Reform-Central

Office, Elliptical Road, Diliman, Quezon City (dated

February 22, 2005) is hereby REVERSED and SET

ASIDE and a new one enteredDECLARING the subject

landholding as the Petitioners retained area. No

pronouncements as to costs.

SO ORDERED.58

Hence, this petition.

Petitioners maintain that the CA committed a reversible error in

declaring the land as Carriedos retained area.59

They claim that Paragraph 4, Section 6 of RA No. 6657 prohibits any

sale, disposition, lease, management contract or transfer of possession of

private lands upon effectivity of the law.60 Thus, Regional Director Renato

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

Id. at 59-60.

Id. at 61.

Id. at 11-47.

Rollo, p. 170-171.

Id. at 171.

Id. at 173-175; 2003 Rules and Procedure Governing Landowner Retention Rights.

Rollo, pp. 177-176.

Id. at 17.

Id. at 18.

Decision

G.R. No. 176549

Herrera correctly observed that Carriedos act of disposing his agricultural

property would be tantamount to his exercise of retention under the law. By

violating the law, Carriedo could no longer retain what was left of his

property. To rule otherwise would be a roundabout way of rewarding a

landowner who has violated the explicit provisions of the Comprehensive

Agrarian Reform Law.61

They also assert that Carriedo waived his right to retain for failure or

neglect for an unreasonable length of time to do that which he may have

done earlier by exercising due diligence, warranting a presumption that he

abandoned his right or declined to assert it.62 Petitioners claim that Carriedo

has not filed an Application for Retention over the subject land over a

considerable passage of time since the same was acquired for distribution to

qualified farmer beneficiaries.63

Lastly, they argue that Certificates of Land Ownership Awards

(CLOAs) already generated in favor of his co-petitioners Corazon Mendoza

and Rolando Gomez cannot be set aside. CLOAs under RA No. 6657 are

enrolled in the Torrens system of registration which makes them

indefeasible as certificates of title issued in registration proceedings.64

The Issue

The sole issue for our consideration is whether Carriedo has the right

to retain the land.

Our Ruling

We rule in the affirmative. Carriedo did not waive his right of retention

over the land.

The 1987 Constitution expressly recognizes landowner retention

rights under Article XIII, Section 4, to wit:

Section 4. The State shall, by law, undertake an agrarian

reform program founded on the right of farmers and regular

farmworkers, who are landless, to own directly or

collectively the lands they till or, in the case of other

farmworkers, to receive a just share of the fruits thereof. To

this end, the State shall encourage and undertake the

just distribution of all agricultural lands, subject to

such priorities and reasonable retention limits as the

Congress may prescribe, taking into account ecological,

developmental, or equity considerations, and subject to the

payment of just compensation. In determining retention

limits, the State shall respect the right of small landowners.

61

62

63

64

Id.

Rollo, pp. 19-20.

Id. at 20.

Id. at 21.

Decision

10

G.R. No. 176549

The State shall further provide incentives for voluntary

land-sharing. (Emphasis supplied.)

RA No. 6657 implements this directive, thus:

Section 6. Retention Limits. Except as otherwise

provided in this Act, no person may own or retain, directly

or indirectly, any public or private agricultural land, the

size of which shall vary according to factors governing a

viable family-size farm, such as commodity produced,

terrain, infrastructure, and soil fertility as determined by the

Presidential Agrarian Reform Council (PARC) created

hereunder, but in no case shall retention by the

landowner exceed five (5) hectares.

xxx

The right to choose the area to be retained, which shall

be compact or contiguous, shall pertain to the landowner:

Provided, however, That in case the area selected for

retention by the landowner is tenanted, the tenant shall have

the option to choose whether to remain therein or be a

beneficiary in the same or another agricultural land with

similar or comparable features. In case the tenant chooses

to remain in the retained area, he shall be considered a

leaseholder and shall lose his right to be a beneficiary under

this Act. In case the tenant chooses to be a beneficiary in

another agricultural land, he loses his right as a leaseholder

to the land retained by the landowner. The tenant must

exercise this option within a period of one (1) year from the

time the landowner manifests his choice of the area for

retention. In all cases, the security of tenure of the farmers

or farmworkers on the land prior to the approval of this Act

shall be respected. xxx (Emphasis supplied.)

In Danan v. Court of Appeals,65 we explained the rationale for the

grant of the right of retention under agrarian reform laws such as RA No.

6657 and its predecessor PD No. 27, to wit:

The right of retention is a constitutionally guaranteed

right, which is subject to qualification by the legislature. It

serves to mitigate the effects of compulsory land

acquisition by balancing the rights of the landowner and the

tenant and by implementing the doctrine that social justice

was not meant to perpetrate an injustice against the

landowner. A retained area, as its name denotes, is land

which is not supposed to anymore leave the landowner's

dominion, thus sparing the government from the

inconvenience of taking land only to return it to the

landowner afterwards, which would be a pointless process.

For as long as the area to be retained is compact or

contiguous and does not exceed the retention ceiling of five

(5) hectares, a landowner's choice of the area to be retained

65

G.R. No. 132759, October 25, 2005, 474 SCRA 113.

Decision

11

G.R. No. 176549

must prevail. xxx66

To interpret Section 6 of RA No. 6657, DAR issued Administrative

Order No. 02, Series of 2003 (DAR AO 02-03). Section 6 of DAR AO 02-03

provides for the instances when a landowner is deemed to have waived his

right of retention, to wit:

Section 6. Waiver of the Right of Retention. The

landowner waives his right to retain by committing any of

the following act or omission:

6.1

Failure to manifest an intention to exercise his right to

retain within sixty (60) calendar days from receipt of

notice of CARP coverage.

6.2

Failure to state such intention upon offer to sell or

application under the [Voluntary Land Transfer

(VLT)]/[Direct Payment Scheme (DPS)] scheme.

6.3

Execution of any document stating that he expressly

waives his right to retain. The MARO and/or PARO

and/or Regional Director shall attest to the due

execution of such document.

6.4

Execution of a Landowner Tenant Production

Agreement and Farmers Undertaking (LTPA-FU) or

Application to Purchase and Farmers Undertaking

(APFU) covering subject property.

6.5

Entering into a VLT/DPS or [Voluntary Offer to Sell

(VOS)] but failing to manifest an intention to exercise

his right to retain upon filing of the application for

VLT/DPS or VOS.

6.6

Execution and submission of any document indicating

that he is consenting to the CARP coverage of his

entire landholding.

6.7

Performing any act constituting estoppel by laches

which is the failure or neglect for an unreasonable

length of time to do that which he may have done

earlier by exercising due diligence, warranting a

presumption that he abandoned his right or declined

to assert it.

Petitioners cannot rely on the RDs Order dated October 2, 2002

which granted Mendozas petition for coverage on the ground that Carriedo

violated paragraph 4 Section 667 of RA No. 6657 for disposing of his

66

67

Id. at 128 citing Daez v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 133507, February 17, 2000, 325 SCRA 856.

Paragraph 4, Section 6 of RA No. 6657 provides:

Upon the effectivity of this Act, any sale, disposition, lease, management,

contract or transfer of possession of private lands executed by the original landowner

in violation of the Act shall be null and void: Provided, however, That those

executed prior to this Act shall be valid only when registered with the Register of

Deeds within a period of three (3) months after the effectivity of this Act. Thereafter,

Decision

12

G.R. No. 176549

agricultural land, consequently losing his right of retention. At the time

when the Order was rendered, up to the time when it was affirmed by the

DAR-CO in its Order dated February 22, 2005, the applicable law is Section

6 of DAR 02-03. Section 6 clearly shows that the disposition of agricultural

land is not an act constituting waiver of the right of retention.

Thus, as correctly held by the CA, Carriedo [n]ever committed any

of the acts or omissions above-stated (DAR AO 02-03). Not even the sale

made by the herein petitioner in favor of PLFI can be considered as a waiver

of his right of retention. Likewise, the Records of the present case is bereft

of any showing that the herein petitioner expressly waived (in writing) his

right of retention as required under sub-section 6.3, section 6, DAR

Administrative Order No. 02-S.2003. 68

Petitioners claim that Carriedos alleged failure to exercise his right of

retention after a long period of time constituted a waiver of his retention

rights, as envisioned in Item 6.7 of DAR AO 02-03.

We disagree.

Laches is defined as the failure or neglect for an unreasonable and

unexplained length of time, to do that which by exercising due diligence

could or should have been done earlier; it is negligence or omission to assert

a right within a reasonable time, warranting a presumption that the party

entitled to assert it either has abandoned it or declined to assert it.69 Where a

party sleeps on his rights and allows laches to set in, the same is fatal to his

case.70

Section 4 of DAR AO 02-03 provides:

Section 4. Period to Exercise Right of Retention under

RA 6657

68

69

70

4.1

The landowner may exercise his right of retention at

any time before receipt of notice of coverage.

4.2

Under the Compulsory Acquisition (CA) scheme, the

landowner shall exercise his right of retention within

sixty (60) days from receipt of notice of coverage.

4.3

Under the Voluntary Offer to Sell (VOS) and the

Voluntary Land Transfer (VLT)/Direct Payment

Scheme (DPS), the landowner shall exercise his right

of retention simultaneously at the time of offer for

sale or transfer.

all Registers of Deeds shall inform the Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR)

within thirty (30) days of any transaction involving agricultural lands in excess of

five (5) hectares.

Rollo, p. 140.

Olizon v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 107075, September 1, 1994, 236 SCRA 148, 157-158.

Periquet, Jr. v. Intermediate Appellate Court, G.R. No. 69996, December 5, 1994, 238 SCRA 697.

Decision

13

G.R. No. 176549

The foregoing rules give Carriedo any time before receipt of the

notice of coverage to exercise his right of retention, or if under compulsory

acquisition (as in this case), within sixty (60) days from receipt of the notice

of coverage. The validity of the notice of coverage is the very subject of the

controversy before this court. Thus, the period within which Carriedo should

exercise his right of retention cannot commence until final resolution of this

case.

Even assuming that the period within which Carriedo could exercise

his right of retention has commenced, Carriedo cannot be said to have

neglected to assert his right of retention over the land. The records show that

per Legal Report dated December 13, 199971 prepared by Legal Officer Ariel

Reyes, Carriedo filed an application for retention which was even contested

by Pablo Mendozas son, Fernando.72 Though Carriedo subsequently

withdrew his application, his act of filing an application for retention belies

the allegation that he abandoned his right of retention or declined to assert it.

In their Memorandum73 however, petitioners, for the first time, invoke

estoppel, citing DAR Administrative Order No. 05 Series of 200674 (DAR

AO 05-06) to support their argument that Carriedo waived his right of

retention.75 DAR AO 05-06 provides for the rules and regulations governing

the acquisition and distribution of agricultural lands subject of conveyances

under Sections 6, 7076 and 73 (a)77 of RA No. 6657. Petitioners particularly

cite Item no. 4 of the Statement of Policies of DAR AO 05-06, to wit:

II.

Statement of Policies

4. Where the transfer/sale involves more than the five (5)

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

DARAB Records (A-9999-03-CV-008-03), pp. 445-448.

Id. at 448.

Rollo, pp. 237-251.

Guidelines on the Acquisition and Distribution of Agricultural lands Subject of Conveyance

Under Sections 6, 70 and 73 (a) of RA No. 6657.

Rollo, pp. 241-245.

Section 70 of RA No. 6657 reads:

Section 70. Disposition of Private Agricultural Lands. The sale or disposition

of agricultural lands retained by a landowner as a consequence of Section 6 hereof

shall be valid as long as the total landholdings that shall be owned by the transferee

thereof inclusive of the land to be acquired shall not exceed the landholding ceilings

provided for in this Act. Any sale or disposition of agricultural lands after the

effectivity of this Act found to be contrary to the provisions hereof shall be null and

void. Transferees of agricultural lands shall furnish the appropriate Register of Deeds

and the [Barangay Agrarian Reform Committee (BARC)] an affidavit attesting that

his total landholdings as a result of the said acquisition do not exceed the

landholding ceiling. The Register of Deeds shall not register the transfer of any

agricultural land without the submission of this sworn statement together with proof

of service of a copy thereof to the BARC.

Section 73 (a) of RA No. 6657 reads:

Section 73. Prohibited Acts and Omissions. The following are prohibited:

(a)

The ownership or possession, for the purpose of

circumventing the provisions of this Act, of agricultural lands in

excess of the total retention limits or award ceilings by any person,

natural or juridical, except those under collective ownership by

farmer-beneficiaries;

xxx

Decision

14

G.R. No. 176549

hectares retention area, the transfer is considered violative

of Sec. 6 of R.A. No. 6657.

In case of multiple or series of transfers/sales, the first five

(5) hectares sold/conveyed without DAR clearance and the

corresponding titles issued by the Register of Deeds (ROD)

in the name of the transferee shall, under the principle of

estoppel, be considered valid and shall be treated as the

transferor/s retained area but in no case shall the

transferee exceed the five-hectare landholding ceiling

pursuant to Sections 6, 70 and 73(a) of R.A. No. 6657.

Insofar as the excess area is concerned, the same shall

likewise be covered considering that the transferor has no

right of disposition since CARP coverage has been vested

as of 15 June 1988. Any landholding still registered in the

name of the landowner after earlier dispositions totaling an

aggregate of five (5) hectares can no longer be part of his

retention area and therefore shall be covered under CARP.

(Emphasis supplied.)

Citing this provision, petitioners argue that Carriedo lost his right of

retention over the land because he had already sold or disposed, after the

effectivity of RA No. 6657, more than fifty (50) hectares of land in favor of

another.78

In his Memorandum,79 Carriedo maintains that petitioners cannot

invoke any administrative regulation to defeat his right of retention. He

argues that administrative regulation must be in harmony with the

provisions of law otherwise the latter prevails.80

We cannot sustain petitioners' argument. Their reliance on DAR AO

05-06 is misplaced. As will be seen below, nowhere in the relevant

provisions of RA No. 6657 does it indicate that a multiple or series of

transfers/sales of land would result in the loss of retention rights. Neither do

they provide that the multiple or series of transfers or sales amounts to the

waiver of such right.

The relevant portion of Section 6 of RA No. 6657 referred to in Item

no. 4 of DAR AO 05-06 provides:

Section 6. Retention Limits. Except as otherwise

provided in this Act, no person may own or retain, directly

or indirectly, any public or private agricultural land, the

size of which shall vary according to factors governing a

viable family-size farm, such as the commodity produced,

terrain, infrastructure, and soil fertility as determined by the

Presidential Agrarian Reform Council (PARC) created

hereunder, but in no case shall retention by the landowner

78

79

80

Rollo, p. 245.

Id. at 214-236.

Id. at 227, citing Philippine Petroleum Corp., v. Municipality of Pililla, Rizal, G.R. No. 90776,

June 3, 1991, 198 SCRA 82.

Decision

15

G.R. No. 176549

exceed five (5) hectares. xxx

Upon the effectivity of this Act, any sale, disposition,

lease, management, contract or transfer of possession of

private lands executed by the original landowner in

violation of the Act shall be null and void: Provided,

however, That those executed prior to this Act shall be

valid only when registered with the Register of Deeds

within a period of three (3) months after the effectivity of

this Act. Thereafter, all Registers of Deeds shall inform the

Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) within thirty (30)

days of any transaction involving agricultural lands in

excess of five (5) hectares. (Emphasis supplied.)

Section 70 of RA No. 6657, also referred to in Item no. 4 of DAR AO

05-06 partly provides:

The sale or disposition of agricultural lands retained by

a landowner as a consequence of Section 6 hereof shall be

valid as long as the total landholdings that shall be owned

by the transferee thereof inclusive of the land to be

acquired shall not exceed the landholding ceilings provided

for in this Act. Any sale or disposition of agricultural

lands after the effectivity of this Act found to be

contrary to the provisions hereof shall be null and void.

xxx (Emphasis supplied.)

Finally, Section 73 (a) of RA No. 6657 as referred to in Item No. 4 of

DAR AO 05-06 provides,

Section 73. Prohibited Acts and Omissions. The

following are prohibited:

(a) The ownership or possession, for the purpose of

circumventing the provisions of this Act, of

agricultural lands in excess of the total retention

limits or award ceilings by any person, natural or

juridical, except those under collective ownership

by farmer-beneficiaries; xxx

Sections 6 and 70 are clear in stating that any sale and disposition of

agricultural lands in violation of the RA No. 6657 shall be null and void.

Under the facts of this case, the reasonable reading of these three provisions

in relation to the constitutional right of retention should be that the

consequence of nullity pertains to the area/s which were sold, or owned by

the transferee, in excess of the 5-hectare land ceiling. Thus, the CA was

correct in declaring that the land is Carriedos retained area.81

Item no. 4 of DAR AO 05-06 attempts to defeat the above reading by

providing that, under the principle of estoppel, the sale of the first five

hectares is valid. But, it hastens to add that the first five hectares sold

81

Rollo, pp. 142-143.

Decision

16

G.R. No. 176549

corresponds to the transferor/s retained area. Thus, since the sale of the first

five hectares is valid, therefore, the landowner loses the five hectares

because it happens to be, at the same time, the retained area limit. In reality,

Item No. 4 of DAR AO 05-06 operates as a forfeiture provision in the guise

of estoppel. It punishes the landowner who sells in excess of five hectares.

Forfeitures, however, partake of a criminal penalty.82

In Perez v. LPG Refillers Association of the Philippines, Inc.,83 this

Court said that for an administrative regulation to have the force of a penal

law, (1) the violation of the administrative regulation must be made a crime

by the delegating statute itself; and (2) the penalty for such violation must be

provided by the statute itself.84

Sections 6, 70 and 73 (a) of RA No. 6657 clearly do not provide that a

sale or disposition of land in excess of 5 hectares results in a forfeiture of the

five hectare retention area. Item no. 4 of DAR AO 05-06 imposes a penalty

where none was provided by law.

As this Court also held in People v. Maceren,85 to wit:

The reason is that the Fisheries law does not expressly

prohibit electro fishing. As electro fishing is not banned

under the law, the Secretary of Agriculture and Natural

Resources and the Natural Resources and the

Commissioner of Fisheries are powerless to penalize it. In

other words, Administrative Order Nos. 84 and 84-1, in

penalizing electro fishing, are devoid of any legal basis.

Had the lawmaking body intended to punish electro

fishing, a penal provision to that effect could have been

easily embodied in the old Fisheries Law.86

The repugnancy between the law and Item no. 4 of DAR AO 05-06 is

apparent by a simple comparison of their texts. The conflict undermines the

82

83

84

85

86

See Cabal v. Kapunan, Jr., G.R. No. L-19052, December 29, 1962, 6 SCRA 1059, 1064:

Such forfeiture has been held, however, to partake the nature of a penalty.

In a strict signification, a forfeiture is a divestiture of property

without compensation, in consequence of a default or an offense, and

the term is used in such a sense in this article. A forfeiture, as thus

defined, is imposed by way of punishment, not by the mere

convention of the parties, but by the lawmaking power, to insure a

prescribed course of conduct. It is a method deemed necessary by the

legislature to restrain the commission of an offense and to aid in the

prevention of such an offense. The effect of such a forfeiture is to

transfer the title to the specific thing from the owner to the sovereign

power. (23 Am. Jur. 599)

In Blacks Law Dictionary, a forfeiture is defined to the the

incurring of a liability to pay a definite sum of money as the

consequence of violating the provisions of some statute or refusal to

comply with some requirement of law. It may be said to be a penalty

imposed for misconduct or breach of duty. (Com. Vs. French, 114

S.W. 255)

G.R. No. 159149, June 26, 2006, 492 SCRA 638.

Id. at 649.

G.R. No. L-32166, October 18, 1977, 79 SCRA 450.

Id. at 456.

Decision

17

G.R. No. 176549

statutorily-guaranteed right of the landowner to choose the land he shall

retain, and DAR AO 05-06, in effect, amends RA No. 6657.

In Romulo, Mabanta, Buenaventura, Sayoc & De Los Angeles

(RMBSA) v. Home Development Mutual Fund (HDMF),87 this Court was

confronted with the issue of the validity of the amendments to the rules and

regulations implementing PD No. 1752.88 In that case, PD No. 1752 (as

amended by RA No. 7742) exempted RMBSA from the Pag-Ibig Fund

coverage for the period January 1 to December 31, 1995. In September

1995, however, the HDMF Board of Trustees issued a board resolution

amending and modifying the rules and regulations implementing RA No.

7742. As amended, the rules now required that for a company to be entitled

to a waiver or suspension of fund coverage, it must have a plan providing for

both provident/retirement and housing benefits superior to those provided in

the Pag-Ibig Fund. In ruling against the amendment and modification of the

rules, this Court held that

In the present case, when the Board of Trustees of the

HDMF required in Section 1, Rule VII of the 1995

Amendments to the Rules and Regulations Implementing

R.A. No. 7742 that employers should have both

provident/retirement and housing benefits for all its

employees in order to qualify for exemption from the Fund,

it effectively amended Section 19 of P.D. No. 1752. And

when the Board subsequently abolished that exemption

through the 1996 Amendments, it repealed Section 19 of

P.D. No. 1752. Such amendment and subsequent repeal of

Section 19 are both invalid, as they are not within the

delegated power of the Board. The HDMF cannot, in the

exercise of its rule-making power, issue a regulation not

consistent with the law it seeks to apply. Indeed,

administrative issuances must not override, supplant or

modify the law, but must remain consistent with the law

they intend to carry out. Only Congress can repeal or

amend the law.89 (Citations omitted; underscoring

supplied.)

Laws, as well as the issuances promulgated to implement them, enjoy

the presumption of validity.90 However, administrative regulations that alter

or amend the statute or enlarge or impair its scope are void, and courts not

only may, but it is their obligation to strike down such regulations.91 Thus, in

this case, because Item no. 4 of DAR AO 05-06 is patently null and void, the

presumption of validity cannot be accorded to it. The invalidity of this

87

88

89

90

91

G.R. No. 131082, June 19, 2000, 333 SCRA 777.

Amending the Act Creating the Home Development Mutual Fund (1980).

Supra note 88 at 786.

Dasmarias Water District v. Monterey Foods Corporation, G.R. No. 175550, September 17,

2008, 565 SCRA 624 citing Tan v. Bausch & Lomb Inc., G.R. No. 148420, December 15, 2005, 478

SCRA 115, 123-124, citing Walter E. Olsen & Co. v. Aldanese and Trinidad, 43 Phil. 259 (1922) and

San Miguel Brewer, Inc. v. Magno, G.R. No. L-21879, September 29, 1967, 21 SCRA 292.

California Assn. of Psychology Providers v. Rank, 51 Cal 3d 1, 270 Cal Rptr 796, 793 P2 2 (1980)

citing Dyna-med, Inc. v. Fair Employment & Housing Com., 43 Cal.3d 1379, 1388-1389 (1987) and

Hittle v. Santa Barbara County Employees Retirement Assn., 39 Cal.3d 374, 387 (1985).

Decision

18

G.R. No. 176549

provision constrains us to strike it down for being ultra vires.

In Conte v. Commission on Audit,92 the sole issue of whether the

Commission on Audit (COA) acted in grave abuse of discretion when it

disallowed in audit therein petitioners' claim of financial assistance under

Social Security System (SSS) Resolution No. 56 was presented before this

Court. The COA disallowed the claims because the financial assistance

under the challenged resolution is similar to a separate retirement plan which

results in the increase of benefits beyond what is allowed under existing

laws. This Court, sitting en banc, upheld the findings of the COA, and

invalidated SSS Resolution No. 56 for being ultra vires, to wit:

xxx Said Sec. 28 (b) as amended by RA 4968 in no

uncertain terms bars the creation of any insurance or

retirement plan other than the GSIS for government

officers and employees, in order to prevent the undue and

[iniquitous] proliferation of such plans. It is beyond cavil

that Res. 56 contravenes the said provision of law and is

therefore invalid, void and of no effect. xxx

We are not unmindful of the laudable purposes for

promulgating Res. 56, and the positive results it must have

had xxx. But it is simply beyond dispute that the SSS had

no authority to maintain and implement such retirement

plan, particularly in the face of the statutory prohibition.

The SSS cannot, in the guise of rule-making, legislate or

amend laws or worse, render them nugatory.

It is doctrinal that in case of conflict between a statute

and an administrative order, the former must prevail. A rule

or regulation must conform to and be consistent with the

provisions of the enabling statute in order for such rule or

regulation to be valid. The rule-making power of a public

administrative body is a delegated legislative power, which

it may not use either to abridge the authority given it by the

Congress or the Constitution or to enlarge its power beyond

the scope intended. xxx Though well-settled is the rule that

retirement laws are liberally interpreted in favor of the

retiree, nevertheless, there is really nothing to interpret in

either RA 4968 or Res. 56, and correspondingly, the

absence of any doubt as to the ultra-vires nature and

illegality of the disputed resolution constrains us to rule

against petitioners.93 (Citations omitted; emphasis and

underscoring supplied.)

Administrative regulations must be in harmony with the provisions of

the law for administrative regulations cannot extend the law or amend a

legislative enactment.94 Administrative issuances must not override, but must

remain consistent with the law they seek to apply and implement. They are

92

93

94

G.R. No. 116422, November 4, 1996, 264 SCRA 19.

Id. at 30-31.

Landbank of the Philippines v. Court of Appeals, G.R. Nos. 118712 & 118745, October 6, 1995,

249 SCRA 149.

Decision

19

G.R. No. 176549

intended to carry out, not to supplant or modify the law.95 Administrative or

executive acts, orders and regulations shall be valid only when they are not

contrary to the laws or the Constitution.96 Administrative regulations issued

by a Department Head in conformity with law have the force of law.97 As he

exercises the rule-making power by delegation of the lawmaking body, it is a

requisite that he should not transcend the bounds demarcated by the statute

for the exercise of that power; otherwise, he would be improperly exercising

legislative power in his own right and not as a surrogate of the lawmaking

body.98

If the implementing rules and regulations are issued in excess of the

rule-making authority of the administrative agency, they are without binding

effect upon the courts. At best, the same may be treated as administrative

interpretations of the law and as such, they may be set aside by the Supreme

Court in the final determination of what the law means.99

While this Court is mindful of the DARs commitment to the

implementation of agrarian reform, it must be conceded that departmental

zeal may not be permitted to outrun the authority conferred by statute.100

Neither the high dignity of the office nor the righteousness of the motive

then is an acceptable substitute; otherwise the rule of law becomes a myth.101

As a necessary consequence of the invalidity of Item no. 4 of DAR

AO 05-06 for being ultra vires, we hold that Carriedo did not waive his right

to retain the land, nor can he be considered to be in estoppel.

Finally, petitioners cannot argue that the CLOAs allegedly granted in

favor of his co-petitioners Corazon and Orlando cannot be set aside. They

claim that CLOAs under RA No. 6657 are enrolled in the Torrens system of

registration which makes them indefeasible as certificates of title issued in

registration proceedings.102 Even as these allegedly issued CLOAs are not in

the records, we hold that CLOAs are not equivalent to a Torrens certificate

of title, and thus are not indefeasible.

CLOAs and EPs are similar in nature to a Certificate of Land Transfer

(CLT) in ordinary land registration proceedings. CLTs, and in turn the

CLOAs and EPs, are issued merely as preparatory steps for the eventual

issuance of a certificate of title. They do not possess the indefeasibility of

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

Commissioner of Internal Revenue v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 108358, January 20, 1995, 240

SCRA 368.

CIVIL CODE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Article 7.

Valerio v. Secretary of Agriculture and Natural Resources, G.R. No. L-18587, April 23, 1963, 7

SCRA 719.

People v. Maceren, supra note 86 at 459.

Cebu Institute of Technology v. Ople, G.R. No. L-58870, December 18, 1987, 156 SCRA 629,

658.

Radio Communications of the Philippines, Inc. v. Santiago, G.R. Nos. L-29236 & L-29247,

August 21, 1974, 58 SCRA 493, 498.

Villegas v. Subido, G.R. No. L-26534, November 28, 1969, 30 SCRA 498, 511.

Rollo, p. 21.

Decision

20

G.R. No. 176549

certificates of title. Justice Oswald D. Agcaoili, in Property Registration

Decree and Related Laws (Land Titles and Deed\), 103 notes, to wit:

Under PD No. 27, beneficiaries arc issued certificates

of land transfers (ClTs) to entitle them to possess lands.

Thereafter, they are issued emancipation patents (EPs) after

compliance with all necessary conditions. Such EPs, upon

their presentation to the Register of Deeds, shall be the

basis for the issuance of the corresponding transfer

certificates of title (TCTs) in favor of the corresponding

beneficiaries.

Under RA No. 6657, the procedure has been simplified.

Only certificates of land ownership award (CLOAs) are

issued, in lieu of EPs, after compliance with all

prerequisites. Upon presentation of the CLOAs to the

Register of Deeds, TCTs are issued to the designated

beneficiaries. CLTs are no longer issued.

The issuance of EPs or CLOAs to beneficiaries does

not absolutely bar the landowner from retaining the area

covered thereby. Under AO No. 2, series of 1994, an EP or

CLOA may be cancelled if the land covered is later found

to be Qart of the landowner's retained area. (Citations

omitted; underscoring supplied.)

The issue, however, involving the issuance, recall or cancellation of

EPs or CLOAs, is lodged with the DAR, icM which has the primary

jurisdiction over the matter. 105

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the Petition is hereby

DENIED for lack of merit. The assailed Decision of the Court of Appeals

dated October 5, 2006 is AFFIRMED. Item no. 4 of DAR Administrative

Order No. 05, Series of 2006 is hereby declared INVALID, VOID and OF

NO EFFECT for being ultra vires.

SO ORDERED.

Associate Justice

WE CONCUR:

103

1()4

105

20 I I En., I'. 758.

Aninao v. Asturias Chemical Industries, Inc., G.R. No. 160420, July 28, 2005, 464 SCRA 526.

Bagongahasa v. Romualdez, G.R. No. 179844, March 23, 2011, 646 SCRA 338.

G.R. No. 176549

Decision

PRESBITERO VELASCO, JR.

Assocjate Justice

CJfairperson

.PERALTA

Associate Justice

REZ

Associate Justice

ATTESTATION

I attest that the conclusions in the above 9ecision had been reached in

consultation before the case was assigned to !J.fe writer of the opinion of the

Court's Division.

PRESBITERr. VELASCO, JR.

Assa iate Justice

Chairper on, Third Division

CERTIFICATION

Pursuant to Section 13, Article VIII of the Constitution, and the

Division Chairperson's attestation, it is hereby certified that the conclusions

in the above Decision had been reached in consultation before the case was

assigned to the writer of the opinion of the Court's Division.

MARIA LOURDES P.A. SERENO

Chief Justice

c::.l'..L~ =~ .~:~:.;::::COPY

WILFRFI/J -/.

-;

~:~

..

FEB 1 7 201g

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- 950 MW Coal Fired Power Plant DesignDocumento78 pagine950 MW Coal Fired Power Plant DesignJohn Paul Coñge Ramos0% (1)

- Petition for Certiorari Denied Without Opinion: Patent Case 98-1972.Da EverandPetition for Certiorari Denied Without Opinion: Patent Case 98-1972.Nessuna valutazione finora

- List of People in Playboy 1953Documento57 pagineList of People in Playboy 1953Paulo Prado De Medeiros100% (1)

- Agricultural TenancyDocumento20 pagineAgricultural TenancyJel LyNessuna valutazione finora

- Installation and User's Guide For AIX Operating SystemDocumento127 pagineInstallation and User's Guide For AIX Operating SystemPeter KidiavaiNessuna valutazione finora

- Petitioner-Appellant vs. vs. Respondent-Appellee Joselito Coloma Bureau of Agrarian Legal AssistanceDocumento2 paginePetitioner-Appellant vs. vs. Respondent-Appellee Joselito Coloma Bureau of Agrarian Legal AssistanceKruxNessuna valutazione finora

- Etsi Guidelines For Antitrust Compliance PDFDocumento8 pagineEtsi Guidelines For Antitrust Compliance PDFAlexis Anne P. ArejolaNessuna valutazione finora

- CD - 5. Napocpr vs. VillamorDocumento2 pagineCD - 5. Napocpr vs. VillamorMykaNessuna valutazione finora

- Gravity Based Foundations For Offshore Wind FarmsDocumento121 pagineGravity Based Foundations For Offshore Wind FarmsBent1988Nessuna valutazione finora

- NPC vs. VillamorDocumento2 pagineNPC vs. VillamorAira Marie M. AndalNessuna valutazione finora

- Awais Inspector-PaintingDocumento6 pagineAwais Inspector-PaintingMohammed GaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Discussion On Agrarian Law CHAR RADocumento13 pagineDiscussion On Agrarian Law CHAR RARobinson FloresNessuna valutazione finora

- Paul Milgran - A Taxonomy of Mixed Reality Visual DisplaysDocumento11 paginePaul Milgran - A Taxonomy of Mixed Reality Visual DisplaysPresencaVirtual100% (1)

- Cases 7.8.2019 PDFDocumento153 pagineCases 7.8.2019 PDFAlexis Anne P. ArejolaNessuna valutazione finora

- Hitt PPT 12e ch08-SMDocumento32 pagineHitt PPT 12e ch08-SMHananie NanieNessuna valutazione finora

- Coderias Vs CiocoDocumento2 pagineCoderias Vs CiocoRalph Christian Lusanta FuentesNessuna valutazione finora

- DAR vs. CarriedoDocumento2 pagineDAR vs. CarriedoRayBradleyEduardo100% (1)

- DAR Vs CarriedoDocumento7 pagineDAR Vs CarriedoSORITA LAWNessuna valutazione finora

- El Salvador V Honduras SummaryDocumento3 pagineEl Salvador V Honduras SummaryAlexis Anne P. ArejolaNessuna valutazione finora

- Us V Purganan DigestDocumento3 pagineUs V Purganan DigestAlexis Anne P. ArejolaNessuna valutazione finora

- American Home Assurance V Tantuco DigestDocumento1 paginaAmerican Home Assurance V Tantuco DigestAlexis Anne P. ArejolaNessuna valutazione finora

- Municipality of Makati Vs CA DigestDocumento1 paginaMunicipality of Makati Vs CA DigestAlexis Anne P. ArejolaNessuna valutazione finora

- 8 - Heirs of Enrique Tan Sr. V Pollescas G.R. No. 145568 November 17 2005Documento13 pagine8 - Heirs of Enrique Tan Sr. V Pollescas G.R. No. 145568 November 17 2005Christine Marie EboNessuna valutazione finora

- Supreme Court: Guevara, Francisco and Recto For Appellant. Mendoza and Clemeña For AppelleeDocumento5 pagineSupreme Court: Guevara, Francisco and Recto For Appellant. Mendoza and Clemeña For AppelleeIris Jianne MataNessuna valutazione finora

- Petitioners Vs VS: Second DivisionDocumento11 paginePetitioners Vs VS: Second DivisionKarloCaezarHomenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ludo & Luym vs. BarrettoDocumento23 pagineLudo & Luym vs. BarrettoShirlyn D. CuyongNessuna valutazione finora

- GR 129165 PDFDocumento10 pagineGR 129165 PDFPrincess AlainneNessuna valutazione finora

- Tan V PollescasDocumento7 pagineTan V PollescasLadyGrace VillalbaNessuna valutazione finora

- Grounds To Dispossess A Lessee and Suppletory EffectDocumento29 pagineGrounds To Dispossess A Lessee and Suppletory EffectMDR Andrea Ivy DyNessuna valutazione finora

- Gua-An Et - Al v. Quirino: AbandonmentDocumento4 pagineGua-An Et - Al v. Quirino: AbandonmentLimar Anasco EscasoNessuna valutazione finora

- Agency and Partnership Nos 28 30Documento13 pagineAgency and Partnership Nos 28 30Jomar TenezaNessuna valutazione finora

- Hilado Vs ChavezDocumento8 pagineHilado Vs ChavezMoon BeamsNessuna valutazione finora

- Antonio V Manahan - ReportDocumento10 pagineAntonio V Manahan - ReportNiel Edar BallezaNessuna valutazione finora

- Agrarian Law (CASE DIGEST) Fatima C. Dela PenaDocumento17 pagineAgrarian Law (CASE DIGEST) Fatima C. Dela PenaFatima Dela PeñaNessuna valutazione finora

- Department of Agrarian Reform, Quezon City & Pablo Mendoza, Petitioners, vs. ROMEO C. CARRIEDO, Respondent G.R. No.176549 January 20, 2016Documento7 pagineDepartment of Agrarian Reform, Quezon City & Pablo Mendoza, Petitioners, vs. ROMEO C. CARRIEDO, Respondent G.R. No.176549 January 20, 2016Earl YoungNessuna valutazione finora

- Petitioners Respondents Alfredo L. EndayaDocumento9 paginePetitioners Respondents Alfredo L. EndayaHADTUGINessuna valutazione finora

- Select Supreme Court Rulings On Agrarian LawDocumento248 pagineSelect Supreme Court Rulings On Agrarian LawYulo Vincent Bucayu PanuncioNessuna valutazione finora

- Agrarian Reform Council, Et Al., When They Ruled That The Constitution and The CARLDocumento2 pagineAgrarian Reform Council, Et Al., When They Ruled That The Constitution and The CARLDindo RoxasNessuna valutazione finora

- 005 Hermoso V CADocumento14 pagine005 Hermoso V CAmjpjoreNessuna valutazione finora

- Endaya vs. CA, 215 SCRA 109 (1992)Documento12 pagineEndaya vs. CA, 215 SCRA 109 (1992)7766yutrNessuna valutazione finora

- Agra CaseDocumento9 pagineAgra CaseAleph JirehNessuna valutazione finora

- Re Jurisdiction - Agricultural Land RA 1199 As Amended by RA 2263Documento5 pagineRe Jurisdiction - Agricultural Land RA 1199 As Amended by RA 2263JoelNessuna valutazione finora

- Hilado Vs ChavezDocumento20 pagineHilado Vs ChavezThea PorrasNessuna valutazione finora

- D E C I S I O N Jardeleza, J.Documento14 pagineD E C I S I O N Jardeleza, J.Aleph JirehNessuna valutazione finora

- ALSLAss 2 CasesDocumento50 pagineALSLAss 2 CasesErimNessuna valutazione finora

- Villarosa Vs DuldulaoDocumento7 pagineVillarosa Vs DuldulaoKharol EdeaNessuna valutazione finora

- Land Distribution and Acquisition - October 22, 2020Documento20 pagineLand Distribution and Acquisition - October 22, 2020Xyvie Dianne D. DaradarNessuna valutazione finora

- Agra DigestsDocumento3 pagineAgra DigestsDjon AmocNessuna valutazione finora

- Ca-G.r. SP 164076 01312023Documento12 pagineCa-G.r. SP 164076 01312023Ailyn Joy PeraltaNessuna valutazione finora

- de Aldecoa Vs Insular Government (G.R. No. 3894. March 12, 1909)Documento4 paginede Aldecoa Vs Insular Government (G.R. No. 3894. March 12, 1909)Ken ChaseMasterNessuna valutazione finora

- Republic Vs Guzman Full TextDocumento5 pagineRepublic Vs Guzman Full TextmaizcornNessuna valutazione finora

- 1) DEPARTMENT OF AGRARIAN REFORM v. CARRIEDODocumento2 pagine1) DEPARTMENT OF AGRARIAN REFORM v. CARRIEDOLex TalionisNessuna valutazione finora

- Caluzor vs. Llanillo Et Al., G.R. No. 155580, July 1, 2015Documento9 pagineCaluzor vs. Llanillo Et Al., G.R. No. 155580, July 1, 2015pennelope lausanNessuna valutazione finora

- Talavera vs. CA PDFDocumento5 pagineTalavera vs. CA PDFLynne AgapitoNessuna valutazione finora

- Provincial Assessor Vs Filipinas Palm PDFDocumento21 pagineProvincial Assessor Vs Filipinas Palm PDFJennilyn Gulfan YaseNessuna valutazione finora

- 9 Ramos v. Secretary of Agriculture and Natural ResourcesDocumento10 pagine9 Ramos v. Secretary of Agriculture and Natural Resourcescool_peachNessuna valutazione finora

- Second Division (G.R. No. 118712. October 6, 1995.)Documento6 pagineSecond Division (G.R. No. 118712. October 6, 1995.)mansikiaboNessuna valutazione finora

- E. Casanova vs. Hord - 8 Phil 125Documento7 pagineE. Casanova vs. Hord - 8 Phil 125Dondi MenesesNessuna valutazione finora

- Magno V FranciscoDocumento21 pagineMagno V FranciscokamiruhyunNessuna valutazione finora

- REYNALDO v. YATCO, G.R. No. 165494, March 20, 2009Documento2 pagineREYNALDO v. YATCO, G.R. No. 165494, March 20, 2009MarkyHeroiaNessuna valutazione finora

- LTD - 20120902 DigestDocumento12 pagineLTD - 20120902 DigestNico BambaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Caluzor vs. LlaniloDocumento3 pagineCaluzor vs. LlaniloSORITA LAWNessuna valutazione finora

- Module 4-C Assigned DigestsDocumento2 pagineModule 4-C Assigned DigestsDora the ExplorerNessuna valutazione finora

- CCC Insurance Vs CADocumento11 pagineCCC Insurance Vs CATahani Awar Gurar100% (1)

- Micking Vda. de Coronel vs. Tanjangco, Jr.Documento15 pagineMicking Vda. de Coronel vs. Tanjangco, Jr.Johzzyluck R. MaghuyopNessuna valutazione finora

- 5abella v. GonzagaDocumento4 pagine5abella v. GonzagaAna BelleNessuna valutazione finora

- Endaya vs. CA PDFDocumento8 pagineEndaya vs. CA PDFLynne AgapitoNessuna valutazione finora

- Gallardo v. BorromeoDocumento3 pagineGallardo v. Borromeonigel alinsugNessuna valutazione finora

- Commonwealth Act 141 The Public Land ActDocumento44 pagineCommonwealth Act 141 The Public Land ActEla Dwyn CordovaNessuna valutazione finora

- Balabat vs. CADocumento6 pagineBalabat vs. CAjimart10Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Works of the Right Honourable Edmund Burke, Vol. 09 (of 12)Da EverandThe Works of the Right Honourable Edmund Burke, Vol. 09 (of 12)Nessuna valutazione finora

- Complying With Competition LawDocumento28 pagineComplying With Competition LawAlexis Anne P. ArejolaNessuna valutazione finora

- Rules of Admissibility CasesDocumento103 pagineRules of Admissibility CasesAlexis Anne P. ArejolaNessuna valutazione finora

- PaleDocumento69 paginePaleAlexis Anne P. ArejolaNessuna valutazione finora

- PALE CasesDocumento110 paginePALE CasesAlexis Anne P. ArejolaNessuna valutazione finora

- Cuevaz v. Muñoz (G.R. No. 140520 December 18, 2000) FactsDocumento3 pagineCuevaz v. Muñoz (G.R. No. 140520 December 18, 2000) FactsAlexis Anne P. ArejolaNessuna valutazione finora

- Separate Opinions Gokongwei V SECDocumento10 pagineSeparate Opinions Gokongwei V SECAlexis Anne P. ArejolaNessuna valutazione finora

- G.R. No. 166471 March 22, 2011 Tawang Multi-Purpose COOPERATIVE Petitioner, La Trinidad Water District, RespondentDocumento36 pagineG.R. No. 166471 March 22, 2011 Tawang Multi-Purpose COOPERATIVE Petitioner, La Trinidad Water District, RespondentAlexis Anne P. ArejolaNessuna valutazione finora

- First Published in The City of Makati", and in Par. 2.04.1, That "This Caricature Was Printed and First Published in The City of Makati"Documento45 pagineFirst Published in The City of Makati", and in Par. 2.04.1, That "This Caricature Was Printed and First Published in The City of Makati"Alexis Anne P. ArejolaNessuna valutazione finora

- Facts:: State Prosecutors Vs MuroDocumento26 pagineFacts:: State Prosecutors Vs MuroAlexis Anne P. ArejolaNessuna valutazione finora

- Globe V. NTC G.R. No. 143964. July 26, 2004 FactsDocumento17 pagineGlobe V. NTC G.R. No. 143964. July 26, 2004 FactsAlexis Anne P. ArejolaNessuna valutazione finora

- Other RulesDocumento15 pagineOther RulesAlexis Anne P. ArejolaNessuna valutazione finora

- Jam V IfcDocumento36 pagineJam V IfcAlexis Anne P. ArejolaNessuna valutazione finora

- PH Competition ActDocumento11 paginePH Competition ActAlexis Anne P. ArejolaNessuna valutazione finora

- Transpo DigestsDocumento23 pagineTranspo DigestsAlexis Anne P. ArejolaNessuna valutazione finora

- Be It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledDocumento37 pagineBe It Enacted by The Senate and House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledAlexis Anne P. ArejolaNessuna valutazione finora

- Hilado and Hilado For Appellants. Parreño, Parreño, and Carreon For Appellees. Hizon and Arboleda For Petitioner Manuel CuisonDocumento27 pagineHilado and Hilado For Appellants. Parreño, Parreño, and Carreon For Appellees. Hizon and Arboleda For Petitioner Manuel CuisonAlexis Anne P. ArejolaNessuna valutazione finora

- 73113521758Documento1 pagina73113521758Alexis Anne P. ArejolaNessuna valutazione finora

- Evid CasesDocumento65 pagineEvid CasesAlexis Anne P. ArejolaNessuna valutazione finora

- Tirol & Tirol For Petitioner. Enojas, Defensor & Teodosio Cabado Law Offices For Private RespondentDocumento10 pagineTirol & Tirol For Petitioner. Enojas, Defensor & Teodosio Cabado Law Offices For Private RespondentAlexis Anne P. ArejolaNessuna valutazione finora

- Historical DocumentsDocumento82 pagineHistorical Documentsmanavjha29Nessuna valutazione finora

- Belimo Fire & Smoke Damper ActuatorsDocumento16 pagineBelimo Fire & Smoke Damper ActuatorsSrikanth TagoreNessuna valutazione finora

- Computer System Architecture: Pamantasan NG CabuyaoDocumento12 pagineComputer System Architecture: Pamantasan NG CabuyaoBien MedinaNessuna valutazione finora

- CT018 3 1itcpDocumento31 pagineCT018 3 1itcpraghav rajNessuna valutazione finora

- Test Bank For American Corrections Concepts and Controversies 2nd Edition Barry A Krisberg Susan Marchionna Christopher J HartneyDocumento36 pagineTest Bank For American Corrections Concepts and Controversies 2nd Edition Barry A Krisberg Susan Marchionna Christopher J Hartneyvaultedsacristya7a11100% (30)

- Chapter 2 A Guide To Using UnixDocumento53 pagineChapter 2 A Guide To Using UnixAntwon KellyNessuna valutazione finora

- Beam Deflection by Double Integration MethodDocumento21 pagineBeam Deflection by Double Integration MethodDanielle Ruthie GalitNessuna valutazione finora

- Types of MemoryDocumento3 pagineTypes of MemoryVenkatareddy Mula0% (1)

- August 2015Documento96 pagineAugust 2015Cleaner MagazineNessuna valutazione finora

- 1980WB58Documento167 pagine1980WB58AKSNessuna valutazione finora

- GATE General Aptitude GA Syllabus Common To AllDocumento2 pagineGATE General Aptitude GA Syllabus Common To AllAbiramiAbiNessuna valutazione finora

- Pega AcademyDocumento10 paginePega AcademySasidharNessuna valutazione finora

- Bank Statement SampleDocumento6 pagineBank Statement SampleRovern Keith Oro CuencaNessuna valutazione finora

- Automatic Stair Climbing Wheelchair: Professional Trends in Industrial and Systems Engineering (PTISE)Documento7 pagineAutomatic Stair Climbing Wheelchair: Professional Trends in Industrial and Systems Engineering (PTISE)Abdelrahman MahmoudNessuna valutazione finora

- Notice For AsssingmentDocumento21 pagineNotice For AsssingmentViraj HibareNessuna valutazione finora

- Fr-E700 Instruction Manual (Basic)Documento155 pagineFr-E700 Instruction Manual (Basic)DeTiEnamoradoNessuna valutazione finora

- AkDocumento7 pagineAkDavid BakcyumNessuna valutazione finora

- A Survey On Multicarrier Communications Prototype PDFDocumento28 pagineA Survey On Multicarrier Communications Prototype PDFDrAbdallah NasserNessuna valutazione finora

- Question Paper: Hygiene, Health and SafetyDocumento2 pagineQuestion Paper: Hygiene, Health and Safetywf4sr4rNessuna valutazione finora

- Surface CareDocumento18 pagineSurface CareChristi ThomasNessuna valutazione finora

- PW Unit 8 PDFDocumento4 paginePW Unit 8 PDFDragana Antic50% (2)

- Quantity DiscountDocumento22 pagineQuantity Discountkevin royNessuna valutazione finora

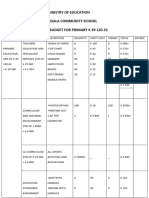

- Ministry of Education Musala SCHDocumento5 pagineMinistry of Education Musala SCHlaonimosesNessuna valutazione finora