Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Improving Diagnostic and Clinical Interviewing

Caricato da

oakley bart100%(1)Il 100% ha trovato utile questo documento (1 voto)

284 visualizzazioni6 pagineImbunatariea interviului clinic

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoImbunatariea interviului clinic

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

100%(1)Il 100% ha trovato utile questo documento (1 voto)

284 visualizzazioni6 pagineImproving Diagnostic and Clinical Interviewing

Caricato da

oakley bartImbunatariea interviului clinic

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 6

Improving Diagnostic and Clinical Interviewing

Oxford Clinical Psychology

Psychologists' Desk Reference (3 ed.)

Edited by Gerald P. Koocher, John C. Norcross, and Beverly A. Greene

Publisher: Oxford University Press

Print ISBN-13: 9780199845491

DOI:

10.1093/med:psych/9780199845491.001.0001

Print Publication Date: Jul 2013

Published online: Jan 2015

Gerald P. Koocher, John C. Norcross, and Beverly

A. Greene

Improving Diagnostic and Clinical Interviewing

Chapter: Improving Diagnostic and Clinical Interviewing

Author(s): Rhonda S. Karg, Arthur N. Wiens, and Ryan W. Blazei

DOI: 10.1093/med:psych/9780199845491.003.0003

Clinical interviews are the foundation of assessment and diagnosis. First and foremost, the

purpose of a clinical interview is to give clients the opportunity to present their unique

perspectives on the reasons they have sought help. From the standpoint of the interviewer, the

purposes of a clinical interview are to gather information about the client and his or (p. 23)

her problems, to establish a relationship with the client that will facilitate assessment and

treatment, and to direct the client in his or her search for relief. Toward these goals, the

following list describes empirically supported and clinically tested guidelines to improve the

efficacy and efficiency of interviews.

1. Prepare for the interview: Before the initial meeting, carefully review the referral

request and other available data. Clients become understandably annoyed by being

asked for information contained in the record and frequently feel slighted by interviewers

who did not take the time to review their files. In a similar vein, interview preparation

should involve becoming well informed regarding the problem areas presented by the

Page 1 of 6

Subscriber: OUP Ox Clinical Psychology FreeAccess; date: 31 March 2015

Improving Diagnostic and Clinical Interviewing

client and symptoms that should be carefully assessed during the interview.

2. Determine the purpose of the interview: Before proceeding with an interview, the

clinician should have a clear understanding of the objectives of the interview. For

example, is the purpose to make a diagnosis, to plan treatment, to initiate psychotherapy,

or all three? In other cases, the interview will accomplish more detailed objectives. For

example, should the client be considered incompetent? Should this patient be released

from the hospital? Along these lines, consider whether the priority should be sensitivity (to

avoid false negatives) or specificity (to avoid false positives). Use this information to guide

the depth and breadth of the interview and the selection of other assessment methods to

complement your interview.

3. Use structured or semistructured diagnostic interviews: By ensuring coverage of

critical areas of functioning and by standardizing the diagnostic assessment, structured

and semistructured interviews enhance diagnostic reliability and validity. Examples of

these include the Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of

Mental Disorders (SCID-I and SCID-II; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1996), the

Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS; Endicott & Spitzer, 1978), and

the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; World Health Organization, 1997).

4. Administer screening instruments: To increase efficiency and improve the accuracy

of the clinical interview, administer psychometrically sound screening instruments

immediately prior to the structured interview. Two of our favorites are the Psychiatric

Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire (Zimmerman & Mattia, 2001) and the SCID Screen

Patient Questionnaire (First et al., 1996).

5. Convey the purpose and parameters of the interview: Present the rationale for the

interview and describe what information you expect the client (or other informant) to

provide. The intent is to give the interviewee a set or an expectation of what will occur

during the interview and why this time is important. Describe the amount of available time,

the type of questions you will ask, the limits of privileged information, and to whom the

interview findings may be reported. Solicit the clients goals and expectations for

completing the interview. Monumental misunderstandings can occur when clinician and

client are not on the same page.

6. Use a collaborative interview style: Put two minds to work and explore problems with

the client. A collaborative interview style not only helps build rapport but also sets the

tone for working together during the course of treatment. By sharing the responsibilities of

their assessment and treatment, clients gain a sense of control and are thereby more

likely to adhere to recommendations and are less likely to complain if their progress is

bumpy.

7. Hear what the interviewee has to say: Clients often express their appreciation that

someone was willing to hear them. Give clients (or other informants) sufficient time to talk

and tell their story in their own ways and words. Listen profoundly; devote 100% of

yourself to the interview, hearing not only what the individual is saying (content) but also

what meaning lies beneath the words (process and emotion). Truly listening to

interviewees is vital to developing rapport and encourages the expression of valid

diagnostic information.

8. Include a comprehensive analysis of the problem behaviors: Begin the functional

analysis of behavior by probing for the three dimensions of problematic behavior:

frequency (how (p. 24) often?), duration (how long?), and intensity (how severe?).

Thoroughly examine the contexts in which the problem behaviors developed and in what

Page 2 of 6

Subscriber: OUP Ox Clinical Psychology FreeAccess; date: 31 March 2015

Improving Diagnostic and Clinical Interviewing

contexts they are most likely to manifest themselves. For example, what was happening in

the life of the person just prior to the onset of symptoms? What internal and external

events appear to trigger or exacerbate the symptoms? What appears to strengthen or

weaken the problem behaviors? Giving serious consideration to environmental or

situational determinants can assist us in making a multiaxial diagnosis (particularly Axis IV,

Psychosocial and Environmental Problems) and might reduce the chance of committing

the fundamental attribution error.

9. Include an assessment of character strengths: As championed by Seligman and

colleagues, the positive psychology movement calls for as much focus on strength as on

weakness. Any interview should include a few moments on what works for the client, not

only on what does not.

10. Anchor verbal assessments with concrete behavioral terms: Take pains to ensure

that the client comprehends the content of the questions. Speak in terms he or she can

understand. Rephrase questions using more concrete or lay terms to help clients grasp

the underlying constructs. Provide examples of the symptoms (especially those that are

denied) and solicit behavioral referents for the symptoms he or she endorses. Ask

questions such as Can you give me an example of what you mean when you say you

are depressed? or On a scale of 110, with 1 being No Desire to Live and 10 being

On Top of the World, how would you rate your current mood?

11. Challenge inconsistent or dubious negative responses: A number of strategies can

be used to challenge questionable data. Our favorites are to (1) ask for more information,

(2) use amplified reflection (e.g., So theres never been a time when you drove after

drinking any alcohol?), (3) point out the inconsistency to the client (e.g., Help me

understand ), or (4) normalize the experience (e.g., Many people feel very upset

when experiencing such a loss. How did you feel after your friend was killed?).

12. Complement the interview with other assessment methods: Clinicians who rely

exclusively on the clinical interview are prone to miss important information. The

comprehensiveness and validity of an interview are enhanced by the use of

psychological testing, behavioral or situational observations, and collateral data from

family or social reports. In fact, research consistently demonstrates that objective

psychological testing (especially actuarially driven) should be used in practically all

diagnostic interviews (e.g., Dawes, Faust, & Meehl, 1989; Meyer et al., 2001). A few of our

favorites are the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 Restructured Form, the

Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory-III, and the Personality Assessment Inventory.

13. Differentiate between skill and motivation: Traditional interviews frequently confuse

a persons skill and motivation. Ask yourself: Does the client have the skills to perform the

behavior in question? If so, is he or she sufficiently motivated? What secondary gains are

maintaining his or her behavior? While interrelated, the two have differing diagnostic and

treatment implications and thus should be clearly delineated.

14. Consider base rates of behaviors: Base rates should guide, in part, the prediction of

behaviors and the establishment of diagnostic decisions (Finn & Kamphuis, 1995). A

corollary is to consider base rates when conducting the clinical interview. Acquire some

knowledge of the frequencies of psychiatric symptoms and disorders in the population

from which the client is drawn. For example, what is the base rate of committing suicide

among older Caucasian males? Consult the extant literature on prevalence rates of

psychiatric disorders across client characteristics, paying particular attention to those

relevant to your professional setting.

Page 3 of 6

Subscriber: OUP Ox Clinical Psychology FreeAccess; date: 31 March 2015

Improving Diagnostic and Clinical Interviewing

15. Avoid common interviewer biases: Although formulating hypotheses is an integral

component of interviews, one must guard against biases that might result in skewing

information and in making incorrect decisions. As described by Meehl (1977), examples of

such biases include a tendency to perceive people very unlike ourselves as being sick

(p. 25) (the sick-sick fallacy), denying the diagnostic significance of an event

because it has also happened to us (the me-too fallacy), and the idea that

understanding clients behaviors strips them of their significance (the understanding-itmakes-it-normal fallacy). Also be mindful of cultural differences that may interfere with

establishing rapport and bias your follow-up probes and diagnostic impressions.

16. Avoid common response biases: Clinical interviewers can exhibit verbal and

nonverbal cues that reveal their opinions or hypotheses about the clients behaviors.

Mindfully demonstrate a nonjudgmental stance to help clients tell their story without

concern that you are judging them, for better or for worse. Avoid leading questions and

statements that may give the client hints about your judgment or hypotheses since these

can lead to response biases. Instead, use open-ended questions and adopt a stance of

innocent curiosity, asking clarifying questions even when you are fairly certain what the

client is referencing.

17. Tailor the interview to the clients characteristics: Be mindful of the clients

characteristics before, during, and after the interview. How does one proceed with a

patient, a client, a student, an adult, a child, an inmate, a job applicant, a felon, or an

athlete? How are interviews tailored for the clients cultural background; the motivated

interviewee versus the reluctant interviewee; patients with different diagnoses;

interviewees wishing to deceive?

18. Delay reaching decisions while the interview is being conducted: Research has

generally shown that the most accurate clinical decision makers tend to arrive at their

conclusions later than do less accurate clinicians (e.g., Elstein, Shulman, & Sprafka,

1978). The clinical implication of these findings is to reserve your diagnostic judgments

until after the interview has been completed so that you are less susceptible to

prematurely terminating data collection.

19. Prepare for ending the interview: Pause and silently review the information that you

have collected. Have you met the objectives of the interview? Is there a part of the

clients story that remains unclear to you? Do you need more information for differential

diagnosis? Are you able to rate the clients functioning (Axis V) with confidence? If you

are missing critical information, decide whether you can fill in the gaps during the current

session or whether you will need to schedule a second interview with the client or a

collateral informant.

20. Provide a proper termination: Anticipate the termination of the interview and prepare

the client accordingly. Point out when time is running short (usually 5 to 10 minutes prior

to ending the interview). One can combine this forewarning with a brief recapitulation,

followed by eliciting the clients reactions to the interview and asking whether there is any

additional topic he or she would like to discuss before ending. If applicable, communicate

your diagnostic impressions and your treatment recommendations. End the interview with

a concluding statement expressing your appreciation and your interest.

21. Employ debiasing strategies: Our natural tendency is to search for supporting

evidence for our expectations. To help combat this bias, employ a disconfirmation

strategy, hunting for information that will disprove initial impressions. What in this protocol

disputes the evidence for, say, schizophrenia? Another debiasing strategy is to make

Page 4 of 6

Subscriber: OUP Ox Clinical Psychology FreeAccess; date: 31 March 2015

Improving Diagnostic and Clinical Interviewing

yourself think about alternatives after you have generated an initial impression (Arkes,

1981). If we find ourselves unable to generate alternatives, it is time to seek consultation

with colleagues. Again, we suggest using base rates and other objective means to help

avoid biases and expectations.

22. Seek supervision and consultation as needed: Clinical interviews and diagnostic

decisions are often complicated by unique and overlapping symptom presentations.

Colleagues are a wellspring of information, insights, and perspectives that we may have

otherwise failed to consider. Remember that peer supervision often benefits both those

seeking and providing consultation, so do not hesitate to ask for help.

References and Readings

Arkes, H. R. (1981). Impediments to accurate clinical judgment and possible ways to minimize

their impact. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 49, 323330.

Dawes, R. M., Faust, D., & Meehl, P. E. (1989). Clinical versus actuarial judgment. Science, 243,

16681674.

Elstein, A. S., Shulman, A. S., & Sprafka, S. A. (1978). Medical problem solving: An analysis of

clinical reasoning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Endicott, J., & Spitzer, R. L. (1978). A diagnostic interview: The Schedule for Affective Disorders

and Schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry, 35, 837844.

Finn, S. E., & Kamphuis, J. H. (1995). What a clinician needs to know about base rates. In J. N.

Butcher (Ed.), Clinical personality assessment (pp. 224235). New York: Oxford University

Press.

First, M. B., Spitzer, R. L, Gibbon, M., & Williams, J. B. W (1996). Structured Clinical Interview for

DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Clinician Version (SCID-CV). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric

Press.

Meehl, P. E. (1977). Why I do not attend case conferences. In P. E. Meehl (Ed.),

Psychodiagnosis: Selected papers (pp. 225302). New York: Norton.

Meyer, G. J., Finn, S. E., Eyde, L. D., Kay, G. G., Moreland, K. L., Dies, R. R., Read, G. M.

(2001). Psychological testing and psychological assessment: A review of evidence and issues.

American Psychologist, 56, 128165.

Wiens, A. N., & Brazil, P. J. (2000). Structured clinical interviews for adults. In G. Goldstein & M.

Hersen (Eds.), Handbook of psychological assessment (pp. 108125). New York: Pergamon.

World Health Organization. (1997). Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI),

Version 2.1. Geneva, Switzerland: Author.

Zimmerman, M., & Mattia, J. L. (2001). A self-report scale to help make psychiatric diagnoses:

The Psychiatric Diagnostic Screening Questionnaire. Archives of General Psychiatry, 58, 787

794.

Page 5 of 6

Subscriber: OUP Ox Clinical Psychology FreeAccess; date: 31 March 2015

Improving Diagnostic and Clinical Interviewing

Related Topics

Chapter 2, Conducting a Mental Status Examination

Chapter 4, Increasing the Accuracy of Clinical Judgment

Chapter 8, Interviewing Childrens Caregivers

Chapter 13, Using the International Classification of Diseases System (ICD-10)

Chapter 16, Assessing Personality Disorders

Page 6 of 6

Subscriber: OUP Ox Clinical Psychology FreeAccess; date: 31 March 2015

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- SReYA Assessment Tools and FormsDocumento23 pagineSReYA Assessment Tools and FormsReyrhye Ropa92% (13)

- Bipolar II Depression Questionnaire-8 Item (BPIIDQ-8) : S2 TableDocumento2 pagineBipolar II Depression Questionnaire-8 Item (BPIIDQ-8) : S2 TableLuís Gustavo Ribeiro100% (1)

- Altman Self Rating ScaleDocumento2 pagineAltman Self Rating ScaleRifkiNessuna valutazione finora

- Case PresentationDocumento10 pagineCase PresentationViseshNessuna valutazione finora

- Structured Clinical Interview For The DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID PTSD Module)Documento2 pagineStructured Clinical Interview For The DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID PTSD Module)Doomimummo100% (1)

- Psychological Assessment Fifth EditionDocumento15 paginePsychological Assessment Fifth EditionDiky Derriansyah20% (5)

- Case Conceptualization 514Documento4 pagineCase Conceptualization 514Kyle RossNessuna valutazione finora

- Beck Youth ReviewDocumento8 pagineBeck Youth ReviewalexutzadulcikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Assessment ToolsDocumento74 pagineAssessment ToolsSharvari ShahNessuna valutazione finora

- The Unstructured Clinical InterviewDocumento8 pagineThe Unstructured Clinical Interviewkasmiantoabadi100% (1)

- Y Bocs Information SampleDocumento2 pagineY Bocs Information SampledevNessuna valutazione finora

- Clinical Interviewing SkillsDocumento27 pagineClinical Interviewing SkillsAcademic Committe100% (1)

- Application of Neuropsychological Assessments On Various Areas of Life, Issues, Challenges and Prospects in Indian ContextDocumento14 pagineApplication of Neuropsychological Assessments On Various Areas of Life, Issues, Challenges and Prospects in Indian ContextShreyasi Vashishtha100% (1)

- Diagnostic FormulationDocumento8 pagineDiagnostic FormulationAnanya ReddyNessuna valutazione finora

- Psychoeducation: 19 July 2018 Unit VI Topic DiscussionDocumento26 paginePsychoeducation: 19 July 2018 Unit VI Topic DiscussionDana Franklin100% (1)

- Introduction To Clinical and Counselling Psychology 06Documento36 pagineIntroduction To Clinical and Counselling Psychology 06Ram LifschitzNessuna valutazione finora

- Adult Cognitive AssessmentDocumento15 pagineAdult Cognitive AssessmentClaudia Delia Foltun0% (2)

- Clinical AssessmentDocumento26 pagineClinical Assessment19899201989100% (2)

- Neuropsychological Test Scores, Academic Performance, and Developmental Disorders in Spanish-Speaking ChildrenDocumento20 pagineNeuropsychological Test Scores, Academic Performance, and Developmental Disorders in Spanish-Speaking ChildrenEilis A. BraceroNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Presentation StyleDocumento7 pagineCase Presentation StyleNiteshSinghNessuna valutazione finora

- CV For Dr. Keely KolmesDocumento9 pagineCV For Dr. Keely KolmesdrkkolmesNessuna valutazione finora

- Psychology Assignment 3Documento5 paginePsychology Assignment 3sara emmanuelNessuna valutazione finora

- Report Template For Children and AdolescentsDocumento21 pagineReport Template For Children and AdolescentsMarry Jane Rivera Sioson100% (1)

- Causes and Risk Factors For Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity DisorderDocumento8 pagineCauses and Risk Factors For Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity DisorderFranthesa LayloNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 7 Mood DisordersDocumento29 pagineChapter 7 Mood DisordersPeng Chiew LowNessuna valutazione finora

- MMPI Administration and ScoringDocumento2 pagineMMPI Administration and ScoringSidra AsgharNessuna valutazione finora

- APA - DSM 5 Diagnoses For Children PDFDocumento3 pagineAPA - DSM 5 Diagnoses For Children PDFharis pratamsNessuna valutazione finora

- Clinical Psych NotesDocumento9 pagineClinical Psych Notesky knmt100% (1)

- Clinical Diagnosis of Alzheimer's Disease (1984, Neurology)Documento8 pagineClinical Diagnosis of Alzheimer's Disease (1984, Neurology)robertokutcherNessuna valutazione finora

- Adhd - Asrs .ScreenDocumento4 pagineAdhd - Asrs .ScreenKenth GenobisNessuna valutazione finora

- Thematic Apperception Test 8Documento8 pagineThematic Apperception Test 8api-610105652Nessuna valutazione finora

- Clinical InterviewingDocumento16 pagineClinical Interviewingaimee2oo880% (5)

- CV Vivek Benegal 0610Documento16 pagineCV Vivek Benegal 0610bhaskarsg0% (1)

- CDI Patient VersionDocumento9 pagineCDI Patient VersionalotfyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Assessment Scales For Obsessivecompulsive Disorder NeuropsychiatryDocumento8 pagineAssessment Scales For Obsessivecompulsive Disorder NeuropsychiatryDebbie de Guzman100% (1)

- The Mental Status ExaminationDocumento4 pagineThe Mental Status ExaminationMeow100% (1)

- The Draw-A-Person Test: An Indicator of Children's Cognitive and Socioemotional Adaptation?Documento18 pagineThe Draw-A-Person Test: An Indicator of Children's Cognitive and Socioemotional Adaptation?JohnNessuna valutazione finora

- Clinical Interview and ObservationDocumento47 pagineClinical Interview and Observationmlssmnn100% (1)

- Psydclpsy PDFDocumento55 paginePsydclpsy PDFReeshabhdev GauttamNessuna valutazione finora

- Assessment of Personality DisorderDocumento19 pagineAssessment of Personality DisorderTanyu Mbuli TidolineNessuna valutazione finora

- Neuropsychology in IndiaDocumento16 pagineNeuropsychology in IndiaRahula RakeshNessuna valutazione finora

- Key Words: Neuropsychological Evaluation, Standardized AssessmentDocumento20 pagineKey Words: Neuropsychological Evaluation, Standardized AssessmentRALUCA COSMINA BUDIANNessuna valutazione finora

- The Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale PDFDocumento21 pagineThe Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale PDFTri Anny Rakhmawati0% (1)

- Guidelines For Psychological Testing of Deaf and Hard of Hearing StudentsDocumento23 pagineGuidelines For Psychological Testing of Deaf and Hard of Hearing StudentsMihai Predescu100% (1)

- Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory TestDocumento26 pagineMinnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory TestGicu BelicuNessuna valutazione finora

- Counselling Pschology UNIT-1Documento7 pagineCounselling Pschology UNIT-1NehaNessuna valutazione finora

- P02 - An Integrative Approach To PsychopathologyDocumento30 pagineP02 - An Integrative Approach To PsychopathologyTEOFILO PALSIMON JR.Nessuna valutazione finora

- MoCA 7.2 ScoringDocumento5 pagineMoCA 7.2 Scoringszhou52100% (2)

- Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) : Expanded VersionDocumento29 pagineBrief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) : Expanded VersionNungki TriandariNessuna valutazione finora

- Interference Score Stroop Test-MainDocumento13 pagineInterference Score Stroop Test-MainNur Indah FebriyantiNessuna valutazione finora

- 20170309160340S2017 - 2 - Clinical Interview, Clinical Observation and Clinical AssessmentDocumento46 pagine20170309160340S2017 - 2 - Clinical Interview, Clinical Observation and Clinical Assessmentnoratikah binti mat taharin100% (1)

- Cns 6161 Treatment Plan - WalterDocumento7 pagineCns 6161 Treatment Plan - Walterapi-263972200Nessuna valutazione finora

- Measures of AnxietyDocumento6 pagineMeasures of AnxietySusana DíazNessuna valutazione finora

- Trail Making Test A and B Normative DataDocumento12 pagineTrail Making Test A and B Normative DataVivi Patarroyo MNessuna valutazione finora

- A Filled-In Example: Schema Therapy Case Conceptualization FormDocumento10 pagineA Filled-In Example: Schema Therapy Case Conceptualization FormKarinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ethics of Psychological AssessmentDocumento31 pagineEthics of Psychological AssessmentAhmad Irtaza AdilNessuna valutazione finora

- Writing A Psychological Report (Finished)Documento10 pagineWriting A Psychological Report (Finished)Lester SagunNessuna valutazione finora

- PMHNP Case Study - EditedDocumento7 paginePMHNP Case Study - EditedSoumyadeep BoseNessuna valutazione finora

- Essentials of TAT and Other Storytelling AssessmentsDa EverandEssentials of TAT and Other Storytelling AssessmentsNessuna valutazione finora

- 2.-Brownlie Human RightsDocumento13 pagine2.-Brownlie Human Rightsoakley bartNessuna valutazione finora

- Despre Aparenta Contradictie Dintre Drept Si Morala 2011Documento12 pagineDespre Aparenta Contradictie Dintre Drept Si Morala 2011Mariana TibuleacNessuna valutazione finora

- CaseDocumento2 pagineCaseoakley bartNessuna valutazione finora

- Carti PT Grup PDFDocumento99 pagineCarti PT Grup PDFoakley bartNessuna valutazione finora

- Poppy Report PDFDocumento40 paginePoppy Report PDFoakley bartNessuna valutazione finora

- STIDS2013 T04 TecuciEtAlDocumento8 pagineSTIDS2013 T04 TecuciEtAloakley bartNessuna valutazione finora

- Structured Analytic TechniquesDocumento45 pagineStructured Analytic Techniquesoakley bartNessuna valutazione finora

- The Entire Endocrinology Lectures Set PDFDocumento385 pagineThe Entire Endocrinology Lectures Set PDFoakley bartNessuna valutazione finora

- Basic Neuroanatomy Neurophysiology RussiaDocumento63 pagineBasic Neuroanatomy Neurophysiology RussiaAnonymous GzRz4H50FNessuna valutazione finora

- Neurobiology of ADHD CuratoloDocumento36 pagineNeurobiology of ADHD Curatolooakley bartNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 SGH PDFDocumento5 pagine1 SGH PDFoakley bartNessuna valutazione finora

- Cognition and MetACOGNITIONDocumento11 pagineCognition and MetACOGNITIONHilierima MiguelNessuna valutazione finora

- 3.2.1 Problem Solving Part 1 and Part 2Documento7 pagine3.2.1 Problem Solving Part 1 and Part 2Carlos jhansien SerohijosNessuna valutazione finora

- Biology 1 End-of-Course Assessment Test Item SpecificationsDocumento115 pagineBiology 1 End-of-Course Assessment Test Item SpecificationszacktullisNessuna valutazione finora

- Stroop TestDocumento4 pagineStroop Testken machimbo0% (1)

- Kepentingan Ca Dalam IndustriDocumento25 pagineKepentingan Ca Dalam IndustriHazwani SaparNessuna valutazione finora

- Lab Report GuidelineDocumento9 pagineLab Report GuidelineAnonymous KpLy2NeNessuna valutazione finora

- TOC Unit 5 PDFDocumento17 pagineTOC Unit 5 PDFKniturseNessuna valutazione finora

- To Kill A Mockingbird Character Analysis EssayDocumento3 pagineTo Kill A Mockingbird Character Analysis Essayapi-252657978100% (1)

- Ethics in ResearchDocumento16 pagineEthics in Researchpinky271994Nessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 4 Requirement EngineeringDocumento39 pagineChapter 4 Requirement EngineeringsanketNessuna valutazione finora

- Mac MKD StyleguideDocumento47 pagineMac MKD Styleguidetaurus_europeNessuna valutazione finora

- Research Proposal and Seminar On Translation - VDocumento3 pagineResearch Proposal and Seminar On Translation - VRi On OhNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan: Faculty of English Linguistics and LiteratureDocumento9 pagineLesson Plan: Faculty of English Linguistics and LiteratureTrúc Nguyễn Thị ThanhNessuna valutazione finora

- Python (ML Ai Block Chain) Projects - 8977464142Documento7 paginePython (ML Ai Block Chain) Projects - 8977464142Devi Reddy Maheswara ReddyNessuna valutazione finora

- Oral Com. G 11 Week 1 2 2Documento8 pagineOral Com. G 11 Week 1 2 2Kimaii PagaranNessuna valutazione finora

- Developing Professional-Level Language Proficiency: Betty Lou LeaverDocumento24 pagineDeveloping Professional-Level Language Proficiency: Betty Lou LeaverDeNessuna valutazione finora

- Sped 405 para Interview ReflectionDocumento4 pagineSped 405 para Interview Reflectionapi-217466148Nessuna valutazione finora

- SINGLE STATE PROBLEM Group 3Documento11 pagineSINGLE STATE PROBLEM Group 3Marvin Lachica LatagNessuna valutazione finora

- Itl 520 Week 1 AssignmentDocumento7 pagineItl 520 Week 1 Assignmentapi-449335434Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Quantum Resonance Revised: An Unfinished Theory of LifeDocumento14 pagineThe Quantum Resonance Revised: An Unfinished Theory of LifeMatt C. KeenerNessuna valutazione finora

- Archie EssayDocumento3 pagineArchie EssayArchie FernandezNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson PlanDocumento10 pagineLesson Plancoboy24Nessuna valutazione finora

- LCS Basics Revesion PDFDocumento3 pagineLCS Basics Revesion PDFrajeshmholmukheNessuna valutazione finora

- Grammar Corner 4Documento130 pagineGrammar Corner 4Luz SierraNessuna valutazione finora

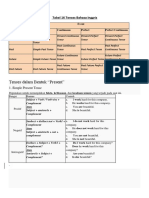

- Tabel 16 Tenses Bahasa InggrisDocumento8 pagineTabel 16 Tenses Bahasa InggrisAnonymous xYC2wfV100% (1)

- Sub-Conscious MindDocumento5 pagineSub-Conscious Mindburhanuddin bhavnagarwalaNessuna valutazione finora

- Fuzzy Jerry M. MendelDocumento2 pagineFuzzy Jerry M. MendelJuan Pablo Rodriguez HerreraNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit TestDocumento6 pagineUnit TestTCHR KIMNessuna valutazione finora

- Prepositions of LocationDocumento8 paginePrepositions of LocationIndah PriliatyNessuna valutazione finora