Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

TEACHERS GUIDE Effective Questioning Techniques

Caricato da

Evelyn Grace Talde TadeoDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

TEACHERS GUIDE Effective Questioning Techniques

Caricato da

Evelyn Grace Talde TadeoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

LEEP: Teachers Guide

Effective Questioning Techniques

Questioning techniques are a heavily used, and thus widely researched, teaching strategy.

Research indicates that asking questions is second only to lecturing. Teachers typically

spend anywhere from 35 to 50 percent of their instructional time asking questions.

Teachers ask questions for a variety of purposes, including:

to actively involve students in the lesson

to increase motivation or interest

to evaluate students preparation

to check on completion of work

to develop critical thinking skills

to review previous lessons

to nurture insights

to assess achievement or mastery of goals and objectives

to stimulate independent learning

A teacher may vary his or her purpose in asking questions during a single lesson, or a

single question may have more than one purpose. Traditionally, educators have classified

questions according to Blooms Taxonomy. While some researchers have simplified

classification of questions into lower and higher cognitive questions. Lower cognitive

questions (fact, closed, direct, recall, and knowledge questions) involve the recall of

information. Higher cognitive questions (open-ended, interpretive, evaluative, inquiry,

inferential, and synthesis questions) involve the mental manipulation of information to

produce or support an answer.

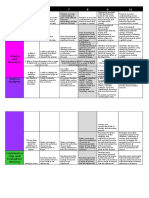

Techniques for effective questioning:

Technique

Process

Prepare your students

for extensive

questioning.

Teachers who use lots of questions in a classroom might have to justify

their use of questioning to students. Some students conclude that

questions imply evaluation, monitoring, and efforts to control students.

Students need to know that questions seek clarification and elaboration of

students' ideas in order to make their thinking visible, and to help the

teacher address misconceptions.

Use both pre-planned

and emerging questions.

Prepare your discussion by identifying the goal and pre-plan a number of

questions that will help achieve the goal. Recall that there are a number of

discussion types designed to introduce new concepts, focus the discussion

on certain items, steer the discussion in specific directions, or identify

student knowledge level on the topic. Questions derived from the

discussion itself can help guide the discussion.

Use a wide variety of

questions.

It is best to begin a discussion by asking divergent questions, and moving

to convergent questions as the goal is approached. Questions should be

asked that require a broad range of intellectual (higher and lower order)

thinking skills. Use Bloom's Taxonomy or Rhodes Typology for a guide to

the type of questions you can ask. Avoid using simple YES or NO type

questions as they encourage students to respond without fully thinking

through an idea.

Technique

Process

Avoid the use of

rhetorical questions.

Rhetorical questions are those to which answers are already known, or

merely seek affirmation of something stated previously such as the

following: Right?, Don't you?, Correct?, Okay?, and Yes? More often than

not, rhetorical questions are unintentional, and are suggestive of habit or

nervousness.

State questions with

precision.

Poor wording and the use of rapid-fire, multiple questions related to the

same topic can result in confusion. Easy does it. Repeat the question, and

explain it in other words if students don't seem to understand. One

question at a time or else students won't know how to respond.

Pose whole-group

questions unless

seeking clarification.

Direct questions to the entire class. Handle incomplete or unclear

responses by reinforcing what is correct and then asking follow-up

questions.Ask for additional details, seek clarification of the answer, or ask

the student to justify a response. Redirect the question to the whole group

of the desired response is not obtained.

Use appropriate wait

time.

Wait time encourages all students to think about the response, as they do

not know who is going to be called upon to answer the question.The

teacher can significantly enhance the analytic and problem-solving skills of

students by allowing sufficient wait times before responding, both after

posing a question and after the answer is given. This allows everyone to

think about not only the question but also the response provided by the

student. Three to five seconds in most cases; longer in some, maybe up to

10 seconds for higher-order questions.

Select both volunteers

and non-volunteers to

answer questions.

Female students frequently take longer to respond; give them adequate

time to do so. Picking on the student who is first to raise his or her hand

will often leave many students uninvolved in the discussion. Some

teachers use a randomized approach where they pick student names from

a hat, so to speak. This ensures equitable participation, and keeps

students intellectually engaged.

Respond to answers

provided by students.

Listen carefully to your students as they respond; let them finish their

responses unless they are completely missing the point. "Echo" their

responses in your own words. Acknowledge correct answers and provide

positive reinforcement. Identify incorrect responses and ask for alternative

explanations from other students. Repeat student answers when the other

students have not heard the answers.

Maintain a positive class

atmosphere.

Not all students will be completely clear in their thinking or enunciation

and, invariably, some won't be paying attention. Nevertheless, avoid the

use of sarcasm, unreasonable reprimands, accusations, and personal

attacks.

Throw back student

questions.

Sometimes student will restate the teachers questions in their own words

and ask the teacher for a response -- getting the teacher to do the

intellectual work. When such an event occurs, restate the question, and

pose it to the class.

Interrelate previous

comments.

As the discussion moves along, be certain to interrelate previous student

comments in an effort to draw a conclusion. Avoid doing the work of

arriving at a conclusion for your student.

Technique

Process

Restate discussion goal

periodically.

Sometimes the purpose of a discussion will become clouded, and even go

off topic. Periodically restate the goal of the discussion so that it is clearly

before the students. It is particularly important to ask questions near the

end of your discussion that help make it clear whether or not the goal has

been achieved. Identify areas in need of clarification.

Take your time.

Hard intellectual work takes considerable effort, and students might not be

terribly familiar with the thought processes required to draw conclusions.

Much of there education might have required them merely to parrot back

things previously told them. Don't give up on students. If a discussion is

worth doing at all, it is worth doing correctly.

Equitably select

students.

Remember that males have a tendency to "jump up and shout out"

responses whereas females tend to be more circumspect and, therefore,

delayed in responding. Control situations where inequitable responding is

likely to occur.

Source:

Questioning Techniques: Research-based Strategies for Teachers. <http://

beyondpenguins.ehe.osu.edu/issue/energy-and-the-polar-environment/questioningtechniques-research-based-strategies-for-teachers>

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Educational Technology A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionDa EverandEducational Technology A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- English Y12 Syllabus Foundation Course PDFDocumento21 pagineEnglish Y12 Syllabus Foundation Course PDFapi-250740140Nessuna valutazione finora

- Differentiated Series of Lesson Plans and Justification StatementDocumento8 pagineDifferentiated Series of Lesson Plans and Justification Statementapi-480163952Nessuna valutazione finora

- Douglas (2008) Using Formative Assessment To Increase LearningDocumento8 pagineDouglas (2008) Using Formative Assessment To Increase LearningMarta GomesNessuna valutazione finora

- Learner Profile and Learning PlanDocumento3 pagineLearner Profile and Learning Planapi-249159360Nessuna valutazione finora

- Methods of Teaching English As A Foreign Language PDFDocumento4 pagineMethods of Teaching English As A Foreign Language PDFAlvaro BabiloniaNessuna valutazione finora

- Classroom TalkDocumento8 pagineClassroom Talkapi-340721646Nessuna valutazione finora

- Inclusive 2h2018assessment1 EthansaisDocumento8 pagineInclusive 2h2018assessment1 Ethansaisapi-357549157Nessuna valutazione finora

- Barrett's and Bloom's TaxonomyDocumento10 pagineBarrett's and Bloom's Taxonomygpl143Nessuna valutazione finora

- Reflection - RefhennesseyjDocumento13 pagineReflection - Refhennesseyjapi-231717654Nessuna valutazione finora

- Tws Reflection and CritiqueDocumento5 pagineTws Reflection and Critiqueapi-265180782Nessuna valutazione finora

- 4Cs Rubrics K-3Documento7 pagine4Cs Rubrics K-3Nicole Tomaselli100% (1)

- Scaffolding in Teacher - Student Interaction: A Decade of ResearchDocumento26 pagineScaffolding in Teacher - Student Interaction: A Decade of ResearchTriharyatiNessuna valutazione finora

- Curriculum Model ChartDocumento2 pagineCurriculum Model Chartapi-243099840Nessuna valutazione finora

- Principle of Lesson PlanningDocumento92 paginePrinciple of Lesson Planninggarfeeq0% (1)

- Retrieval-Based Learning Active Retrieval Promotes Meaningful LearningXXXDocumento12 pagineRetrieval-Based Learning Active Retrieval Promotes Meaningful LearningXXXLuis GuardadoNessuna valutazione finora

- Evaluation and Assessment: Group 6Documento23 pagineEvaluation and Assessment: Group 6Paulene EncinaresNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan 2Documento3 pagineLesson Plan 2api-450523196Nessuna valutazione finora

- 2019 Inductive Versus Deductive Teaching MethodsDocumento21 pagine2019 Inductive Versus Deductive Teaching MethodsAlanFizaDaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Evaluating Speaking Guidelines Spring2006Documento17 pagineEvaluating Speaking Guidelines Spring2006Doula BNNessuna valutazione finora

- Philosophy of EducationDocumento3 paginePhilosophy of Educationapi-510363641Nessuna valutazione finora

- Explicit or Implicit Grammar TeachingDocumento1 paginaExplicit or Implicit Grammar TeachingKory BakerNessuna valutazione finora

- Education in Thailand EssayDocumento4 pagineEducation in Thailand Essayapi-253585742100% (1)

- Assessment For Learning - (3 - Assessment Approaches)Documento16 pagineAssessment For Learning - (3 - Assessment Approaches)YSNessuna valutazione finora

- Active Learning Strategies - NEWDocumento20 pagineActive Learning Strategies - NEWarnel o. abudaNessuna valutazione finora

- CH 6 AssignmentDocumento5 pagineCH 6 AssignmentMarleny SanchezNessuna valutazione finora

- Student Teaching Experience ReflectionDocumento2 pagineStudent Teaching Experience Reflectionapi-302381669Nessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter - 9 - Making InferencesDocumento17 pagineChapter - 9 - Making InferencesGaming User100% (1)

- Strategies For MotivationDocumento19 pagineStrategies For MotivationTogay Balik100% (14)

- Project Based Learning ProposalDocumento1 paginaProject Based Learning ProposalTom GillsonNessuna valutazione finora

- AnswersDocumento5 pagineAnswersSambad BasuNessuna valutazione finora

- Assessing Assessment Literacy and Practices Among Lecturers: Seyed Ali Rezvani Kalajahi, Ain Nadzimah AbdullahDocumento17 pagineAssessing Assessment Literacy and Practices Among Lecturers: Seyed Ali Rezvani Kalajahi, Ain Nadzimah AbdullahNguyễn Hoàng Diệp100% (1)

- Syllabus of Language TestingDocumento4 pagineSyllabus of Language TestingElza Shinta Fawzia100% (1)

- HQOE 1 Fundamental To Curriculum FullDocumento100 pagineHQOE 1 Fundamental To Curriculum FullellsNessuna valutazione finora

- Inquiry Based-Good Chart With Diff 1Documento17 pagineInquiry Based-Good Chart With Diff 1api-252331860Nessuna valutazione finora

- 01 Unit 10 Option 1 Lesson 1Documento26 pagine01 Unit 10 Option 1 Lesson 1Angely A. FlorentinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Tpack Framework Challenges and Opportunities in Ef PDFDocumento22 pagineTpack Framework Challenges and Opportunities in Ef PDFJojames GaddiNessuna valutazione finora

- Philosophy of Classroom Management Final ResubmissionDocumento7 paginePhilosophy of Classroom Management Final Resubmissionapi-307239515Nessuna valutazione finora

- How Students Learn SandraDocumento35 pagineHow Students Learn SandraMgcini Wellington NdlovuNessuna valutazione finora

- Teaching AssistantDocumento5 pagineTeaching AssistantdiscoveryschoolNessuna valutazione finora

- Reflection On Teaching DevelopmentDocumento2 pagineReflection On Teaching DevelopmentBenjamin WinterNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan RubricDocumento3 pagineLesson Plan Rubricapi-452943700Nessuna valutazione finora

- 21 - Maths - Unit PlanDocumento6 pagine21 - Maths - Unit Planapi-526165635Nessuna valutazione finora

- Impact On Students Learning ReflectionDocumento4 pagineImpact On Students Learning Reflectionapi-308414337Nessuna valutazione finora

- University of Education Lahore Department of EnglishDocumento20 pagineUniversity of Education Lahore Department of EnglishGTA V GameNessuna valutazione finora

- Critical Thinker NaureenDocumento20 pagineCritical Thinker NaureenYasmeen JafferNessuna valutazione finora

- Types of Alternative Assessments.Documento3 pagineTypes of Alternative Assessments.bojoiNessuna valutazione finora

- Geography Lesson PlanDocumento4 pagineGeography Lesson Planapi-282153633Nessuna valutazione finora

- Gradual Release of Responsibility ModelDocumento4 pagineGradual Release of Responsibility Modelapi-262031303100% (1)

- InfusionDocumento9 pagineInfusionSheikhLanMapeala100% (1)

- Inquiry-Based LearningDocumento17 pagineInquiry-Based LearningFroilan Tindugan100% (1)

- m05 Basic Productivity Tools Lesson IdeaDocumento2 paginem05 Basic Productivity Tools Lesson Ideaapi-553996843Nessuna valutazione finora

- Theories of LearningDocumento13 pagineTheories of Learningbasran87Nessuna valutazione finora

- Philosophy of Assessment 2Documento8 paginePhilosophy of Assessment 2api-143975079Nessuna valutazione finora

- Project Based and Problem Based Learning SummaryDocumento5 pagineProject Based and Problem Based Learning Summaryhusteadbetty100% (1)

- Applying Educational Theory in PracticeDocumento5 pagineApplying Educational Theory in PracticeHenok Moges KassahunNessuna valutazione finora

- Writing Student Learning Objective 12-06-2010 PDFDocumento2 pagineWriting Student Learning Objective 12-06-2010 PDFAbdul Razak IsninNessuna valutazione finora

- Intasc Reflection 6Documento2 pagineIntasc Reflection 6api-302315706Nessuna valutazione finora

- MalqDocumento1 paginaMalqapi-284681753Nessuna valutazione finora

- Minecraft FAQ For DepEdDocumento9 pagineMinecraft FAQ For DepEdEvelyn Grace Talde TadeoNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 AP 7 First Grading Answer KeyDocumento1 pagina1 AP 7 First Grading Answer KeyEvelyn Grace Talde Tadeo100% (3)

- 4 AP 7 Fourth Grading Answer KeyDocumento1 pagina4 AP 7 Fourth Grading Answer KeyEvelyn Grace Talde Tadeo100% (2)

- New TIP Course 3 (DepEd Teacher)Documento106 pagineNew TIP Course 3 (DepEd Teacher)Evelyn Grace Talde Tadeo75% (4)

- 1 Eve Test ConstructionDocumento90 pagine1 Eve Test ConstructionEvelyn Grace Talde TadeoNessuna valutazione finora

- 4 CSS 10 Exam - Fourth GradingDocumento3 pagine4 CSS 10 Exam - Fourth GradingEvelyn Grace Talde Tadeo100% (7)

- 4 CSS 10 Exam - Fourth Grading TOSDocumento1 pagina4 CSS 10 Exam - Fourth Grading TOSEvelyn Grace Talde Tadeo100% (1)

- Elements of A Computer SystemDocumento25 pagineElements of A Computer SystemEvelyn Grace Talde TadeoNessuna valutazione finora

- CSS 9 Exam - First GradingDocumento7 pagineCSS 9 Exam - First GradingEvelyn Grace Talde Tadeo89% (9)

- 4 CSS 10 Exam - Fourth GradingDocumento3 pagine4 CSS 10 Exam - Fourth GradingEvelyn Grace Talde Tadeo100% (7)

- TEACHERS GUIDE Caring Thinking ModelDocumento3 pagineTEACHERS GUIDE Caring Thinking ModelEvelyn Grace Talde TadeoNessuna valutazione finora

- 3 CSS 9 Exam - Fourth GradingDocumento4 pagine3 CSS 9 Exam - Fourth GradingEvelyn Grace Talde Tadeo100% (1)

- Blank TOS EnglishDocumento2 pagineBlank TOS EnglishEvelyn Grace Talde TadeoNessuna valutazione finora

- Jasmine: San Guillermo National High SchoolDocumento1 paginaJasmine: San Guillermo National High SchoolEvelyn Grace Talde TadeoNessuna valutazione finora

- Parental ConsentDocumento1 paginaParental ConsentEvelyn Grace Talde TadeoNessuna valutazione finora

- TEACHERS GUIDE Divergent ThinkingDocumento2 pagineTEACHERS GUIDE Divergent ThinkingEvelyn Grace Talde TadeoNessuna valutazione finora

- TEACHERS GUIDE Extended BrainstormingDocumento2 pagineTEACHERS GUIDE Extended BrainstormingEvelyn Grace Talde TadeoNessuna valutazione finora

- Requirements Checklist For Head Teacher IDocumento1 paginaRequirements Checklist For Head Teacher IEvelyn Grace Talde TadeoNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 Read This FIRST! Learning To ThinkDocumento2 pagine1 Read This FIRST! Learning To ThinkEvelyn Grace Talde TadeoNessuna valutazione finora

- TEACHERS GUIDE Combined Bloom & Krathwohl TaxonomiesDocumento3 pagineTEACHERS GUIDE Combined Bloom & Krathwohl TaxonomiesEvelyn Grace Talde TadeoNessuna valutazione finora

- TEACHERS GUIDE Combined Bloom Taxonomy & Garder MI SampleDocumento2 pagineTEACHERS GUIDE Combined Bloom Taxonomy & Garder MI SampleEvelyn Grace Talde TadeoNessuna valutazione finora

- Teachers Guide Graphic OrganizerDocumento2 pagineTeachers Guide Graphic OrganizerEvelyn Grace Talde Tadeo0% (1)

- Sample Citizens CharterDocumento10 pagineSample Citizens CharterEvelyn Grace Talde TadeoNessuna valutazione finora

- DO - s2016 - 21 Additional Information To DepEd Order No. 42, S. 2015 (High School Graduates Who Are Eligible To Enrol in Higher Education Institutions in SY 2016-2017Documento1 paginaDO - s2016 - 21 Additional Information To DepEd Order No. 42, S. 2015 (High School Graduates Who Are Eligible To Enrol in Higher Education Institutions in SY 2016-2017Evelyn Grace Talde TadeoNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 Read This FIRST! Learning To ThinkDocumento2 pagine1 Read This FIRST! Learning To ThinkEvelyn Grace Talde TadeoNessuna valutazione finora

- Frontline Services Fees Requirements Processing Time (Under Normal Circumstances) Person-In-ChargeDocumento3 pagineFrontline Services Fees Requirements Processing Time (Under Normal Circumstances) Person-In-ChargeEvelyn Grace Talde TadeoNessuna valutazione finora

- Form 137 B. Good Moral: Processing of Request For School Credentials ADocumento2 pagineForm 137 B. Good Moral: Processing of Request For School Credentials AEvelyn Grace Talde TadeoNessuna valutazione finora

- DepED Order No. 42Documento53 pagineDepED Order No. 42IMELDA ESPIRITU100% (15)

- Formative and Summative Assessment Formative AssessmentDocumento11 pagineFormative and Summative Assessment Formative AssessmentClemente AbinesNessuna valutazione finora

- Interim Guidelines For Assessment and GradingDocumento47 pagineInterim Guidelines For Assessment and GradingRodel Camposo100% (1)

- ETHICSDocumento22 pagineETHICSIrish Joy CruzNessuna valutazione finora

- Iste Standards - TeachersDocumento2 pagineIste Standards - Teachersapi-319209865Nessuna valutazione finora

- Vygotsky Vs PiagetDocumento6 pagineVygotsky Vs PiagetRuba Tarshne :)Nessuna valutazione finora

- TeacherpdpallisonDocumento3 pagineTeacherpdpallisonapi-413326138Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan RDPDocumento2 pagineLesson Plan RDPapi-508144451Nessuna valutazione finora

- Syifa Fadlina, Putri Nabila, Erlinda Tiara - Multiple Intelligences Lesson PlanDocumento4 pagineSyifa Fadlina, Putri Nabila, Erlinda Tiara - Multiple Intelligences Lesson PlanPutri NabilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Excerpt From DTL Essay For WeeblyDocumento2 pagineExcerpt From DTL Essay For Weeblyapi-429836174Nessuna valutazione finora

- EDRL 475 - AssessmentGraphicOrganizerDocumento2 pagineEDRL 475 - AssessmentGraphicOrganizerCharissaKayNessuna valutazione finora

- Task 1: Tugasan Cuti SekolahDocumento2 pagineTask 1: Tugasan Cuti SekolahNoor AimanNessuna valutazione finora

- Special Education Teacher Training in France and NorwayDocumento9 pagineSpecial Education Teacher Training in France and NorwaykaskaraitNessuna valutazione finora

- 5E Lesson Plan: Withstanding WeatherDocumento3 pagine5E Lesson Plan: Withstanding Weatherapi-527838306Nessuna valutazione finora

- Module 2 - Lesson Plan ComponentsDocumento5 pagineModule 2 - Lesson Plan ComponentsMay Myoe KhinNessuna valutazione finora

- II. Report Description: On-The-Job Training (OJT) Is A Form of Training Taking Place in A NormalDocumento5 pagineII. Report Description: On-The-Job Training (OJT) Is A Form of Training Taking Place in A NormalCharlene K. Delos SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To Media and Information LiteracyDocumento3 pagineIntroduction To Media and Information LiteracyAnonymous wYyVjWTVibNessuna valutazione finora

- 7s Historical Mystery RubricDocumento2 pagine7s Historical Mystery Rubricapi-310819126Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Review of Research On Project-Based LearningDocumento49 pagineA Review of Research On Project-Based LearningRizka AmaliaNessuna valutazione finora

- Fluency ScreenerDocumento5 pagineFluency Screenerapi-540296556Nessuna valutazione finora

- Jozwiakowski Accepting DifferencesDocumento2 pagineJozwiakowski Accepting Differencesapi-385623488Nessuna valutazione finora

- Action Research Proposal: Mathematics Problem-Solving Skill and Reading ComprehensionDocumento4 pagineAction Research Proposal: Mathematics Problem-Solving Skill and Reading Comprehensionanon_473921561Nessuna valutazione finora

- Research Article OrganizerDocumento4 pagineResearch Article OrganizerMimivontease LasterNessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 14Documento3 pagineUnit 14LoryNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan CDocumento4 pagineLesson Plan Capi-302003110Nessuna valutazione finora

- Bacaan Tambahan Bloom S Taxonomy 2Documento9 pagineBacaan Tambahan Bloom S Taxonomy 2roila sulongNessuna valutazione finora

- Wechsler Intelligence ScaleDocumento13 pagineWechsler Intelligence ScaleAisamuddin Mh100% (2)

- Positive Guidance TechniquesDocumento7 paginePositive Guidance TechniquesFarah NoreenNessuna valutazione finora

- Table FinkDocumento2 pagineTable FinkNadin NomanNessuna valutazione finora

- Inquiry Based LearningDocumento27 pagineInquiry Based LearningMrs Rehan100% (2)