Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Reexamining Rowley PDF

Caricato da

Powhatan Vanhugh BeltonTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Reexamining Rowley PDF

Caricato da

Powhatan Vanhugh BeltonCopyright:

Formati disponibili

REEXAMINING ROWLEY:

A NEW Focus IN SPEClALEDUCATION LAw

Scott F. Joh7UJOn*

... The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)

iMuires t~t students be provided with a Fi'ee and Appmpriate

. Public Education (FAPE). Exactly what FAPE means or

~sis.an.elusive topic. Twenty yeat'8 ago, in Board of

EdUcati9.,.;v. Rowley, the United States Supreme Court held.

~trA.PE .requires servioos that provide students with "some

:edueational benefit."}

Rowley isundoubted1y the most

Un,portantand intluentbU case in .special. education laW'. The

"some ed\lcatiol18lbenefit". standard permeates just about

e~ty aspect of special education because it is the standard

.ap.inst"hich all. semoosareDieasured. Subsequent . cases

ha.iveexpand,ed on thiS "soIDe educational benefit" requirement

~~ha~butitremaiJlsessentially intact today.

Mueh :us been written about Rowley and its .impact in

~.education law. 2

This paper presents a new and

dift"erent perspectiw on Rowley .by. examining the Rowley

ePmdardmr FAPE against the evolving . backdrop of state

etl1icatioJJ8lstandardsand litigation over what constitutes an

adQuate.ed.UC8.tion ~r state oonstitutional law. Applying

tMBe ~.toRowleYs analysis and reasoning, this paper

concludes that the "some educational benefit" standard no

IQDler accurately reflects the requirements of the IDEA.

Rather,. state standards . arid educational adequacy

requ:irem~nts themselveB.provide the substantive requirements

.

."

*.A~ . at

.Law. Stem,. VoJiDslry ... Cal.......n, P.A., CoIMlDl'd,. N_

H&DllN'lUnt, Co-couDee}ia ~tI.Gouenwr, 700 A2d 1863 (N.H. 1997); Pioo&eeor

Of ~, ~. UDiYenity &boola! Law; J.D. F:nmkIio. Pierce La.. C81lter. Tbi,s

~r ill bli.ee41ipoD 11 preeeDtPiOa oriiiiWJy cmm III; the z001 Eclw:atioD :r.w

In8titute .Ilt Fnmklin Pierce Law Ceuwr.. I WouJd lib to thank PIofBIeor Sarah

~1d IiDll ~Mark C. Weber I- their review of IlDd commelltB on tbi8 plIJI8r.

1. .M ofEdtM:. u. &wle:Y. 458 U.s. 178, ZOO (1982).

2. Aaearchof the titerllture sbows that &wlcy is re&reuced in over MO law

review artil:les.

..

561

II

562

B.Y.U. EDUCATION AND LAW JOURNAL

[2003

of FAPE, exceeding the "some educational benefit" benchmark.

Such a conclusion requires a fundamental change in the way

courts, school districts, and, parents view special education

services;

This paper first lays the background for and explains the

Rowley decision. Next, this paper discusses three important

changes since Rowley was decided: (1) litigation over what

constitutes an adequate education understate constitutional

law, (2) state educational standards, and (3) the 1997

amendments to the IDEA, and how' these changes. render

Rowley's "some educational benefits" standarcl invalid. Finally,

this paper concludee with a discussion of how to incorporate

high' educational standards and. expectations into special

education services as required by the amended IDEA.

I. BACKGROUND

The Individuals with Disabilities Education. Act (IDEA)

requires state and local schooL districts to provide students

with disabilities with a "free and appropriate public education"

(FAPE). FAPE is defined by the IDEA as special education and

related servicesthat:

(A) have been provided at public expense...without

charge [to the parents];

(B) meet the standards of the State educational agency;

(C) .include an ~ppropriatepreschool, elementary, or

secondary schooleducation in the State involved; and

(D) are provided in conformity with the student's

individualized education program....3

While the statute provides a basic definition of FAPE, it does

not describe the substantive requirements of FAPE, nor set any

requisite standards or levels. of learning achievement for

students With disabilities. Because of this lack of substance,

courts have. struggled when asked to determine if a school

district has provided FAPE to a student. 5

3. 20 U.S.C. f 1401(8) (West 2002).

4. BeL ofEduc. v. Michael M., 96 F.supp.2cl600, 607 (B.D. W. Va. 2000).

5. See ladonna 1.. Boeckman, Buwwin,g C1Ie Key w Public Educotio,,: 'l"M Effec"

of Judicial DetermiAatio1lll of the Individuals with DiBabume. EdutotW1& Act 01&

DUiabled a"d Non.diBabled Stude",.. 46 Drake L. Rev. 8M, 866-868 (1998).

561]

REEXAMINING ROWLEY

563

In Board of Education v. Rowley, 6 the United States

SUpreme . Court attempted to determine' the substantive

.stand8.idaof FAPE. The pl.tlio.tiff in Rowley argued that FAPE

required .schools tq maximize the potential of handicapped

CbiblrencomJDensuratewith the oPPOIt1JDij;y provided to other

cbildJen.Thetrial court' agreed with' this proportional

maximizatioDstandard, 7 and the Court of Appeals affirmed the

trialcou:rt's decision without much conunent.8

The Supreme',. Court overturned the ciJcuit .court's decision

A.iding . that the IDEA (then known astheEHA or Education

Ilamticapped. Act) did .not require. schools to proportionally

maxhniu the pOtential of handicapped. children. Rather, the

Couit . ~. that.' Congress had more moderate goals in mind.

~S\lpretne Court nilied, upon the text and legislative history

of the statute to find that Congressional intent was only to

Pl'OV:lde a. "basic floor of oppo1'tUDity" to students with

disabilitie$by providing them access to public education as

opposed'tQaddreesiDg the q,uality of education .received oneein

schOO1.9 The Cou:rtstated:

By passing the Act, Congress sought primarily to make

public education available'tobandicapped children. But

in seeking to p ~ such, access to public education,

Congress. did not. impose upon the States any greater

sUbStantive educational standard than .would be

,neOO:ssarY to m&kefJilCh ~88 meaningfUl. ...Thus, the

intent ottbeActwas more to opeD the door of public

education to handicapped children on appropriate terms

.'. than to j1Jal'antee any particular level ofedueation onoe

inside;10'

The Courtdetel"Jirined, . however, that some substantive

starida.rd ,for' FAPE was "implicit'in the oongresaional purpose

of proViding access to a free approPriate public education. "11

The Courtfuund

thatthe substantive,

standard for FAPE

.

.

req~ iJlstruction designed to" meet the unique needs of the

handicapped child. supported by such services as are necessary

- . .

iI. 458 U.S. 176.(1982);

7. &wiey v. Btl. ofEduc. 48& F.Supp.lS28, IS84 (S.D.N.Y. 1980).

8.RowIe, 1I.l:Jd. 01 Educ.,682F.2d 943 (.2d tir. 1980).

9. Rowley; 468 U.S. at 192, 200.

1". [d. at 192.

11. Id. at 200.

564

B.Y.U. EDUCATION AND LAW JOURNAL

[2003

to permit the child "to benefit" .from the instruction. 12 The

Court noted that the statute itself provided a checklist of

requirements for FAPEthat included providing instruction at

public expense and under public supervision, providing

instruction. that both met the State's educational standards

and approximated the grade levels used in the State's regular

education system, .and providing instruction that comported

with the child's individUalized educational plan (1EP)~18

The Court ooncluded. that ."if personalized instruction is

providedwithsu{ficientsupportive services to permit the child

to benefit -froiD the instruction, and the other items on the

definitional checklist are satisfied, the child is receiving a

FAPE as defined by the Act.l. The Court stated that when

deternUning whether a student . benefited from the sentices

provided, "the achievement of passing marks and adva.nrement

from grade.to grade will be one important factor in determining

educational benefit," because passing grades and grade

advancement .were methods of monitoring educational progI'eSB

for students being eduCated in regular cl.assrooms. 15

IL POSTRoWLEY

Subsequent court decisions interpret Rowley to mean that

the IDEA does not require schools to provide students with the

best or optimal education, nor to ensure that they receive

services to enable them to maximjze their potential 16 Instead,

schoolsare obligated only to offer services .that provide "some

educational benefit" to the student. Courts sometimes refer to

this as the "Cadillac versus Chevrolet" argument, with the

student being entitled to a serviceable Chevrolet as opposed to

a luxury Cadillae.l 7

12. ld. at 201.

13. ld. at 189.

14. ld.

15. Id. at 207 n. 28. The Row~ Court relied upon grades when a Btudent is

-mainatreamed- aDd educated in the replar education cluarooms of a public IlCbool

sywiem because it UBumedthat in Bucha situation, "the IYBt8m itself moaiton the

educational prolr888 of the child by adminiatering regular examinatiuna, awarding

grades, and permitting yearly adftllCement to -bieber grade levels fur those children

who attain an adequate kDQwledp of ~ coune material- Id. at 202-08. The value of

grade. tbr etudents who are not mai.netreamed is not &II certain.

16. See e.g. Lerm II. Porelorld Sch. Comm., 998 F.2d 1088 (lBt Cir. 1993).

17. Doe e% reI. Doe II. Bd. of Educ., 9 F.3d 456, 459-460 (6th Cir. 1998);

D

REEXAMlNINGROWLEY

561]

565

Some courts further refine the "some educational benefit"

. standard torequi:re students to achieve a "meaningful benefit,"

or to make. "meaningful progi'esS" in the aJeas where the

student's disability impacts their education. 18 . These courts

hold thatwhUe the IDEA does not requireasehool to maximize

a student'spotAmtial; the Btudent'spotential and ability must

be CQnsideredwbendetemrining whether he or she has

pqreseed and reoeiveded1icational benefit. 19 . Moreover, when

a studeDtdisplays considerable intellectual potential, the IDEA

requ.ires "a great deal Dio!'e than a negligible benefit."20

. De,spite. a .myriad of court decisions on the. topic, school

districts,parents, and courts still. have. little gUidance on bow

to assess FAPE or educational benefit. .The Rowley Court

mentiODedthat grades and advaucement from grade to grade

were factors in assessing benefit for mainstreamed students.

Thus, post-Rowley courts have viewed pa88ing grades and

p:ade~dvancementas important radom whend.etermining if a

student .:received educational benefit. 21 Grades for students

with .disabilities, .however; are often modified and lose their

validity as a measure ofbenefit or progre88. 2i

Somecourts have also looked to academic achievement

testing in addition to grades and grade advancement to

measure. educational benefit.28 These courts have relied upon

"objective" academictestB and scores on SUCC688ive tests to

measure educational benefit. . Courts using this approach,

.

FayBCteviUe v. Perry Sch.lMt., 20 IDELR 1289 (SEA Ohio 1994).

18. HCIUftOIJ bulq. ScIi DiiIt. v. BobI1.Y B., 200 F.8d341, 341 (5&h Cu. 2000); Btl.

ofEdri.c. v. N.E., i72 F:8d288, 247 (8d Cir.lfJ89)(IDEA requine eigniftc8nt InrDiDI

andmeaniDcM bODefit); M.C. a: ret. J.e.v. C. Regl. St:A~ Dita. 81 F.3d 389 (3cI Cir.

19$i);~ 9F.3d at 4S8; 11I>loiid M~ v. CoMml'Ekh. CoB'" 910 F.2d 983, 981 (let

Cu. . ;{t9O)' ("'Ceucreu iDdUbitably. desired eflBctive reeUlta llDd dplOll8tZ'abJe

imp:tove~ fi:Jr the kre ~ ) ; ~ v. Bd. of Educ., 774 F.2d 828, 688 (4tb

CJr.ltHl5);~~v.G1'I!IlJteI' CkJr* CoUiaty SeA; Corp.. 96 F.8upp.2d.811 (S.D. IDd. 2000);

Roli$.v. Fra~Aam SeA. Comm., 44 F .8Upp.2clltM (D. Maa. IlJ88).

19. ~ 172 F.3d lit 147 (be1IIeIitmust be pulled in reJaiion to the child'.

poteutial);)lol(.uuJM., 910 F.3d at 81H (lIC8demic potI8Dtial ODe 1Bctor to be conaidered

wben addies8irig: sAldeDt'a Deeda).

20. llidlJewood, 172F.3cL .U47.

2~. Doe ~ reL v. Ala. St. Dept. of Educ., 915 F.2d 61)1, 666 (11th CU. 1990);

PareAt v. osCeola CoWlly SelL Btl.. 69 F.8upp.3d 1248 <M.D. Fla. 199&).

.22. R.B.v. Walli'll/lltwd; S6 IDBLR 32 (D. Coma. _1).

23. For,example, in ~ ~ Sdto(Jl ~ tbe court reviewed the

~tud.~11 lIOOieaOD the Wooclt:ock Jolmllou udelJileJiice IlDd8chieVemeDt teSt to _

the litudent's JI~ aDd Inmd that tile lICUree shOwed meaningful p!Op888, and

thua.tbe achOol hIId provided tllestodent cFAPE.200 F.3dat lU9-3IlO.

566

B.Y.U. EDUCATION AND LAW JOURNAL

[2003

however,ha-ve .. produced varying results with . similar

information)l. The variance seems to be due to the fact that

courts do not have a substantive standard that defines what a

student should know and be able to do at a given point in time.

As a result, assessing benefit through improvement in test

ecoresbecomes a subjective analysis of whether a gain of a

certain amount is sufticient progrees or not.

The .lack of substantive . standards for FAPE,when

combined the current "Cadillac versus Chevrolet" perspective,

lowers expectations' and facilitates a min;lnalistic view of the

substantive' education.' that students with disabilities are

entitled toreeeive.When Congress reauthorized the IDEA in

1997, it expressly noted that low expectations for students with

disabilities impeded the implementation of the IDEAIII

Congress stated that educating students with disabilities could

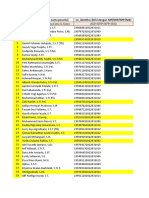

24.. ~ ~ ~ Sc1tDolDUtrid. id. at 860, where the ~

grade equiValent8COltlti weft IJund to demoll8trlUe edacatioDal benefit:

MlJIoIIhide&

Math

Written laDpa.

Pusaae compo

Calculation

Applied problems

.Dictation

:Writing

WOld Identitication

Wold Attack

"""grades

3.1

1.9

5*I6dt grades

1.7

1.5

1.7

U

2.2

,3.3

%.0

8.0

3.6

1.6

1.8

%.8

1.4

2.6

2.1

1.8

2.1

2.6 .

1.8

0.7

~RbadiDB

'~eample8.

Baaic duat.er

2.8

1.8

3.8

3.3

2.1

13

Proofln&

4.4

2.9

3.9

6.0

2.8

2.6

with Hall v. Boord of Education, 1988-1984 EHLR 356:437 (E;D. NC 1988), affd. 774

F.2d629 (4th. Cir. 1985), where tbecourt fbund thattbe fbIJowing teet; scores were fUll

sufticient P!Oareu to pl'OVide educational benefit:

Math

Readinc Recopitjon

Readinc Comp.

. SpeDiDg

GeDBr8l In1b

3"'grade

4.0

2.8

2.2

5.7

2.6

2.7

2.15

3.2

5.3

7.0

25. 20 U .s.C. t14OO(c)(4) (Weat2002).

5*gNle

561}

, REEXAMINING ROWLEY

567

be ,more ~ffectiVe by "having high expectations fur such

childrelland ensuring their access in the general curriculum to

the DUUtimum extentpossible.p26

III. CHANGE IN THE LANDsCAPE

Three important eveD~'occurred after ,the Rowley decision,

all of ' wbich impact the validity of the "some educational

,benefit'" standard and change the nature of educational

serrieE$ that schools must provide studellts' who receive special

'edw:atiQn sentices, under the IDEA. ,The first' sigDificallt 'post

Rowley event is state litigation over the constitutional

'~Dlents of providingtpl "adeq\Ulte" education, to students,

includiDgstudents ,with diSabilities,understate constitutional

law. 'Anac:lequate education under :state constitutional law

reqUires the ~te to provide its', students' with', educational

servi~stargeted tQwards the acquisition of sufficient skills to

bes~ in eociety.&me of these Mqui:rements are at

-od4sWith. and requiie a higher level ofedueational services

than Rowley's "some educational benefit"' standard.

"The'seco.d eyentis tbeeducation standards movement that

~ted 'l;iigh expectations. for, all students, ,including' students

Withdieabilitles, by creatiDg generally applicable content and

Pl"Q~ciency standards.

These standards define academic

,P8rG:tJ1Danre levels and 'provide specific substantive

benChnUlrks that students should achieve during their

acadenriccareel'S.

,

'The third event isthe leauthorization of IDEA in 1997. At

, that'tune, Cp~ .expi'e~ ebanJed, the b:us of the mEA

fi'fnn' genera1accese' to education for childlenwith disabilities

tOhig~ e~tions ~d .~' educationalrQSUltB; Many of the

19&7'~ elilphasiZed that students with disabilities must

be 'P'D'rided with the same quality of ecJucational services

a.beady : provided to students ~ut, disabilities" including

aecessto 'curriculUDl that meets state educational standards.

These three, ,chang~s require a reevaluation of what the

,stattdaNfor FAPE and RiJwley mean today.

26. 20 U.S.c. 1400(c)(4).(5)(A) (WeBt 20(2).

568

B.Y.U. EDUCATION AND LAW JOURNAL

[2003

An Adequate Education under State Constitutional Law

.Most states have state.constitutional provisions requiring

the state to provide educational services to students.27 Forty

four states have been. through. some type of litigation

concerning the educational requirements outlined by their

state constitutions.28 Tbemajority of these cases involved

challenges to. the state'ssy8tem of financing education.

Commentators organize school finance litigation into three

"waves," with some contending the last w8.veis ending and a

potential fourth is beginning.29.

Thefil'st two waves of school finance litigation dealt

p ~ with equal protection.. or equity, arguments

surrounding $Chaol ~g in local school districts. II) The third

wave of echool finance litigation has focused on. whether states

have a conStitUtional obligation to provide a certain level or

qwilityof edu~tion to its students. This qualitative level of

education isoftenrefened to 88 "8Jl.adequate education:'81

. Nwaerous state supreme courts have held that their

constitutions require . the state . to provide an adequate

education to all students.1l2 These d.ec:i$Qnsereate general state

law educational staDdartis aJidieqQirementB. These standards

are subsequently incorporated into the .definition of FAPE for

27. Paula J. Luodberg, State CourtB aIId Schoo' J1undinB.' A Fifty State AMl.1Bi8,

63 Alb. 1.. Rev. 1101, 1167 (2000).

28. William H. CIUDe, F.ducatioIJal~: A Theory CIIId iU.1lnIedia. 28 U.

Mkh. J.L. Ref 481 (1995); ~.Iiapra D. 27; Kevin RaDdaJI McmilIaD, n.

~ Ti4e: The E~ FeanA W'ClVl!of SeItoolFiaonce BiJ(orm. LiIigatio" allod lhe

L~ ~ ~ 18 Ohio 81. U. 186'1 (1998); Deniae C.

Morpn,The 1'(ew Scltoo, .liVIonce. Liti.Ia~tL.' MbowletWiA6 .'I'hat Race Discrimi3otion

in PlWUcEdrM:aoon [sMOre T1Ian JUlle a 7.brc, 96 Nw. U. 1.. Rev. 99 (2001). For current

events On ~ funding Imption" <hUp:/Iwww.a0c8sl8dDet.work.OI.g/index.btmJ>.

29. CI~, ~D. 28; wii1i&m F. Dietz,Mar&a,Jeable Adequac.y Standards in

EducoeiqA:~rm LitiSOlioi&., 7( Wash. U. L.Q. 1198, 1196-1203(1996); Michael Helae.

Stale CoJIIIeicueio,.,. 8c1too' ~ Litigatioi&.,oM' lhe 'Third Wave"l' l'Tom Equity to

AdeqIiac:y.68Temp. 1..Bev.ll1Jl, 11117-119 (l99&);WiUiam B. Thro, ne Bird Wow:

The lrri,pact of lhe ~ ~ . cmd tao. Deeiaiou em lhe Future ef Public

ScItoo,FiN:uu:e &form ~ lfM.L. Educ. 219 (1980).

80. Heise, supra n . .2911t 111571158; Thro,supr'On.29.

81. Kelly. Thompson Cochran,. Beyond

FirIQACins: Defining cAe

ConsCUUCioIlO' RiB"'c to 1M Adeqqoie Edut:otioi&., 78 N.C. 1.. Rev. 399, 413-417 (.1000);

PatriQaF. First. lDuia F. MUon, The M_iJIB or-an Adequate Education. 70 Educ. L.

Rep. 7315, 737 (1992).

S2. Rose II. Counci' for &tW Educ., In.c., 790 S.W.2d 186, 212 (Ky. 1989);

MCDuIb v. Sec. of E:ir:tIt:. Off. 0/ Educ. 6111 N.E.2d 1516; 548(1993); Claremom Sch. Di8t.

eouna;

Sc1aoo'

v. Gov., 708 A~2d 1863. 13156 (N.H. 1997) (Claremone 11).

REEXAMINING ROWLEY

561]

569

students with disabilities by the statutory provision that

requires FAPE to "meet state standards" and include "an

appropriate preschool. elementary, or secondary school

education in the State involved."33

Some courts hold that an adequate education is not a

minimal education. One of the earliest cases to address the

requisite qualitative level of educational services under a state

constitution was Pauley v. Kelly." In Pauley, the West Virginia

Supreme Court described the requisite quality of education

undertbeWe8t. VaginiaConstitution as onetbat "develops, as

best -the state of education .expertise allows, the minds, bodies

a..,ei. soci.almoraJity of its . charges to prepill'e them for useful

aJ).d happy occupations. recreation and citizenship, and does '90

eoonpurically."36

.

The oourt further found that the state had an obligation to

develop

. ,eve:r:y ~dto his or her capacity of (1) literacy; (2)

ability to a4d, subtmct.multiply and divide numbers;

(~) lmowiedle of:g()V~n$to the extelltthat the child

Will be equipped as a citizen to make informed choices

amOnlrJ)eI'8ODS and issUes that affect his own

.governaJi<:e; .(4) seIf~lmow1edge and knowledge of his or

:her total eQ,viromllent to allow the cbild to intelligently

choOse life work to know his or her optio:os; (5) work

'trilimngandadvanced ac;a~emic training as the child

may intelligently choose; (6) recreational pursuits; (7)

i:nte~stsin .all creative arts, suCh as music, theatre,

literatiire, and thevii;ual arts; (8) social ethics, both

behavioral and .abstract, to facilitate compatibility with

others in this 86ciety.86

Some years later, in Alabama Coolilionfor Equity, Inc. v.

. LTtur,t, an Alabama court held that the Alabama oonstitution

required the state to provide students with an education that

would eilBure:

33. 20 U.s.C.A.11401(8)(B), (0) (West ZOO%); NatlReaeucbCou:oc.il, ~

OM .. AU:S~Wi4A~arUlS-dards-Boeed

&torm 51-5! (LonaiDe M.

M

~.

.. PatridaMorieo

, .,.,

. ~

. . J. ~

...

.

D.o., N a tL Aaid.. PIetl8

. lDO'r\

"'u,),

Ifjchael DalilleDberg, ADerivtJtive ~ to Educatiort: How SIaNlDrds-Boeed

.8ducatiOa ~ lWe(iru:a tIle~ with Di.eobilities EducotioB Act, 15 Yale L.

.. PoIicyiev.829, ~l (199'7).

34. 266S.E.2d859 (W. Va. 1979).

35.Id. 877

36. Id.

at

570

B.Y.D. EDUCATION AND LAW JOURNAL

(2003

(viii) sufficient levels of acadenric or vocational skills to

enable public echoolstudents to compete favorably with

their counterparts in Alabama, in surrounding states,

across the nation, and throughout the world, in

academics or in the job market; and

(ix) .sufficient support .and guidance 80 that every

student feels a sense of self-worth and :ability to achieve,

and 80 that every student is encouraged to live up toms

or ber full human potential. 87

State constitutional mandates requiring states to develop

every child to his or her capacib' and enoourage them to live up

to their full human potential are directly at odds with the

Rowley basic floor of opportunity standard. Rowley rejected the

notion that the IDEA itself required states to maximjze a

student's potential. . Ina state where the state's constitution

requires such a stand.ax'd for. all students, however, the

requirement isincorporatedintothe.IDEA's definition ofFAPE

and should be the standard for students with disabilities. ll8

Any other approach would run afoul of the IDEA's

requirements. 89

Other state courts developed and applied similar

constitutional . requirements without express language

reg8.rd.iDg. IDaximising student potential, but these resulting

standm'ds.remamclea:tly contrary to the minimalist guideline

set by Rowley.J . For exampIe,the ~ntucky Supreme Court

decision in RoBe v. Councillor Better Education, Inc. 41 is

considered .one of the .se~lcases. with respect to the

req~JP,e~ts olan adeq~ educatiO~ In Rose, the court

found the state was obligated to provide every child with:

87. Ala. CoolitioFl (or EqrAIy,lnc. I). Hunt, No. CV-90-88S-R (Ala. Cir. Ct. 1998),

reprin"in OpWlm of

Jrutices No.aaa, 624 S.2d 107, 166 (Ala. 1993).

38. NIUl Be.arch CollDl;lil, .u.pro n. S8, at 151-52; Dannenber& IlUIJro n. 33, at

689-48. At the time oi the Rowley decision, litipmn over a state', constitutional

ob~ationB to provide an adequate education was. in its infancy. The Court in Bowley

made . short ehrift of thia requirement in ita decision and did DOt addleu what an

appropriate education would be in Amy Rowley'estate.

89. Providinll difllrent lucatioDal etanclarda ibr students with disabilitiee could

aleoraiile equal protection OODCll!'D8. See Brow" I). BtL of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1915()

(edqcational ~ 8 must be pnMded eq-.Dy to alI).

4O.Thia objective is right in line with the lUD8ndmenta to the IDEA in 1997

discuesed i'ff/ro. The purpose of the IDEA iI DOW to prepare Itudents with diaabilitiell

for independent JmDi. and employment. 20 U.s.C. I 1400(0)(1), (d)(l)(,A) (W..t 2(02).

Thia purpci8e itaelf is arguably incoD8iBtent with Rowle;y~ minimalist approach.

41. 790 S.W.2d 186.

u..

561]

REEXAMINING ROWLEY

571

(i)' sufficient. oral and written communication skills to

enable students to function in 'a complex and rapidly

ch8.nging civilization;

O.i) sufficient knowledge of economic, social, and political

sy8temstoenable the student to .make informed choices;

[m) sufficient undel'8tandingof governmental proresses

to enable' the student to understand the issues that

a:tfecthis or her community, state; and nation;

(iv) sut1icient self-knowlecigeand knowledge of his or

her men.tal and physical wellness;

. (v) s\UD.cientgl'Ounding in the arts to enable each

. student to appreciaW bis or her cultural and historical

heritage;

(vi)' .suft'icient training or preparation. fOr advanced

training ill either academic or weational fields 80 as to

enable . . eachc1rild 'to choose andpUI'SUe life work

intelligently; and

(vij)s~nt~ls of academic or vocational skills to

epablepublie school~ntsto .COJDpetefavorably with

thEtiI"COUn1;erpatts in sUrrotmding states, in academics

or in the ioti market.u

.

Several other state$UpJ,'elD~ ~ have. also adopted the

seven' eriteria.set forth in .RoBe as requirements under .their

state .'... ooDBtltution&.43

These courts . clearly hold a

.OE)ristitptioDlllJ,yadequate education is not aJD,inimal edu~tion.

The New ~pslrire 'Supreme Court stated in Claremont v.

Governor (ClaretnonJ Il),

'.

Given the 'compleXities of'ollr sooiety today, the State's

constitutio,mu duty,. ~Dds beyond' mere reading,

writi:ng, ' apd arithmetic.. It also, . includes broad

e4~~tional' opportunities. needed in today's society to

p~ .cit~Da fortheiT role as participants and as

pOW~t.UdCODlpetitqnintoday'8

m arketplace of ideas. A

eonstitutioJ;18Jly a:deq~te p~lic education is not a static

concept remWedfrom.

de~. 'of an evolving

world:. It is not the needs of the few but the critical

requirements of the' many .that it must address. Mere

thee

42. Id.at 212.

43. Seee.ll. Me1Juff:y, 615 N.E.2d at 554; Claremo,,', 708 A.2d at IM9.

572

RY.U. EDUCATION AND LAW JOURNAL

[2003

competence in the basic&--reading, writing, and

arithmetic-is insufficient in the waning days of the

twentieth century to insure that this State's public

school students are fully integrated into the world

around them; A broadexposure to the social, economic,

scientific. technological, and political realities of today's

society. is essential for our students to compete,

contribute, and :flourish in the tWenty-first century."

When states ." properly . incorporate these oonstitutional

requirements into the IDEA's definition of FAPE, students

with educatiolialdisabilities become entitled to more than just

a basic :floor of opportunity or some educational benefit. They

areentit1ed to receive an education enabling meaningful

participation in a delllOCftltic8Qciety, as weD as competition for

post-secondary education andeDiployment opportunities.46

The IDEA requires. i.ncoiporation . of broad educatiolial

adequacy goals into an .individual edueZiQnal Program (IEP)

meeting the uniq. needs of eaehindiviciual disabled student.

Every stUdent "'ith a disability, as defined by the IDEA, is

entitled .to .an IEP under the IDEA4(l An . IEP must be

indiVidu.aUy tailored to meet the unique needeofthe student"7

The IEP is the cornerstone of proViding FAPE." CoUrts look to

whether an IEP is appropriate when assesSing whether a

school district has provided FAPE."

Aligning IEPswith a state's oC()Qstitutionalrequire'inents

regarding. ail adequate education, .presents. challenging issues

for school officials and parents. Educatore and fa.milies must

boildolVnbroadadequacygoalstoa per8()nalized and detailed

plan fur a specifiestudent~ An IEP must contain Specific goals

and. objectives" to meet the student's uniqueneed.s, as well as

outline the special education and related.eervices the student

will~ive to meet the goals andobjectives;49

When the state coristitutiolUtladeqU8.CY requirements are

incol'Pon'lted 'into .theIEP .process; the goals, objectives, the

44,. ~ 103A2d.e 1StJ9,

46. See e.g. ~, 790 S.W.ldat212; Claremollt, 708 A.U at 1869; Abbot. I).

Burke. 698 A2cl417, .428 (N.J; 1991).

46. 34 C.F.R.,800.841(aXl) (2002).

47. BOllig tI. Doe. 484 U.s; 306, 311 (199$); RolaMM., 910 F.2d at 987.

48. BMiB. 484 U.s. at 811; Pihl v. MCJ88. Dep. of Educ. 9 F;3d 184. 187 (l8t Cir.

1998); Roland M., 910 F.2d at 987; DauidD. I). Dartmouth Sch. Comm. 775 F.2d 411,

415 (let Cir. 1985).

49. 84C.F.R. 800.347 (2002).

II

REEXAMINING ROWLEY

561]

573

special education, and related. services must be targeted

towards enabling the student to meet the educational adequacy

requirements. .The broad .educational adequacy requirements

aloneJDaY nOt be specific enough to enable schools and parents

to . readily meet thiBreqUit'eDlent. IIi this respect, state

educational standards can assiBt by providing specific,

measurable st8.ndardsestabJi,sbing what students should know

and-be able to dO at certain stages in their academic

prDjJtession. 15O Thesesta.ndards can be individuaJizedand

inOOrPoratedinto students' IEPs.

B. State Educational Standards

checklist of FAPE. referenced by the

inRowlq includes a requirement that the

~CatiOn .provided to students. with .disabilities meet state

Btandards;61 When the Court decided Rowley, this requirement

did. notba~ the same meaniDg it does today. Most state

standa.rds at the time oltbe decision did not involve

substantive reqllirements. for. the educational services provided

to .studen~.. Instead, the standards addreesed -the process by

whiebt4eserviees would be provided and were deSigned to be

"minimum" standards. 51

_. However, today the focus of educational standards has

ch8nle~tState and ~ educational standards addre88 the

eNential oo:re of knowledge of what students should learn.

Known in. the edueational worldu ..standards~based education

re~,"etate and f'ederaleducational standards now include

oontent .. Standartis specifying what students -should learn,

proficie~. .. ~ndards ... settiDgthe expectations for what

8~etlts must koow and be able to do at certain stages, and

. asee88~ meaeures determining whether the student has

TlIe.ID~s definitional

SUpl'eJlle

COurt

achiev~tbe .expectations in the. standards. 158

.50. MJuy' E. MoraD, SIaadards- :and.~ n.rNew Mea8rIre 0{ ~

iiI..&/IiOOl MIIOIICe ~ 25 J. fit Edue. Fin. 33 (1998); Coc:hnm, supra D. 31. at

462-64.

51. 28 U~_C.A. 11401(8)(b) <W- 2002).

52, Ff;lr ~Ie, in New Hamp8bil'e, the IItat8 has ~ -DliJiiaum studards"

since . nnach\v. ;

TheBe~. IIIIdnee ioputil liIte the nUJJlber of eredita

8i~ mqiltilaave to pad. . ., h .._raJ. coaree that lIChooJa m_ of etudIIIDte (ie,

~. ~~~ ut8, ete); the _of cIalI8rooma. etc. .They also lIddnea lJChool

operatjopal . .~ like

Of ~lUId claMrooma; teacher certification, etc.

See N.JI. Ilept.:.,F.clue,MiDimDDl St8Dda., ED 300, d ..,.

53. NatL .R8aeama Co1mciI. Brq1J"a rL sa, at S, U. 27-28, 88-40, 113-18; LBt:we No

J953-

* ..

574

B.Y.U. EDUCATION AND LAW JOURNAL

[2003

The standards based education reform eBort became

prominent at the national level with Goals 2000. This federal

law proposed national education goals requiring states

receiving funds under the program to develop strategies for

meeting national education standards. These strategies,

moreover, . had to include . developing and adopting state

education standards and asseument methods. 54

.Other federal .laws like Title I of. the Elementary and

Secondary Education Act, as. amended by the Improving

America's Schools Act of 1994, require states to develop or

adopt chalJenging content, proficiency standards, and

aesessment m:ech8njsms.'~5 Under Title I, students who receive

Title I services must make adequate yearly progress toward

meetillg the .state staildards. ll8 Schools.whose students do not

make adequate progress must develop .coJ7ec=ti.ve action plans.57

The passage of the No childLeft Behind Act of 2001

<NCLB)58 greatly expanded the .8:C0P8. of Title fs requirements

and reatlirmed the federal goVernment's position that all

students should meet bigh academic standards. 59 Schools with

.

Child Behilld Act, !O. U .s.c. fGa02 (Weet IOO~ GoaUI 3000: Educate Americ:o .Ad,

Pub. 1.. No. 1~22'7, f3, 188 Stat. 125, 129-30(2001).

. MSee Title llI,.Section. 306 of GoalsJtJOO: Educate American Act, 108 Stat. at

160-67 (2002) (ixIdiIied at; 20 UB.C. f 5888 (repealed 1999.

M. EIem.en.tary & Secondary .~I'& Ad 88 ameDded by the ImprovilaB

America's &hoolsAct of IIH; Pub.L. No. 108-382. lOS Stat. 8518 (1997).

56. [d.

57.Id.

58. No Child Left &Aind.Adof8001, Pub. 1.. No; 107110, 116 Stat;. 1425 (2002)

(~at .U.s.C. H 83016777 (2000.

59. The NoClNld Left ~.A 1Jf:iI1IIop ~ MIa, prepued by the

~ of tbeUQiDd States Department of Educ:atjon, begins Wit;h a IDeIl88P

from PNlident; Geo!p W.B..h that; states:

The NCLB Act; is desiped. to help an 8tUd8Dt8 IlUl8thirh, academic standards

by requiring . that; sta_create 8DnUill asseasmentl t;hat measure what

children bow and can do in readiDtr and mat;h in grades 8 thl'Ougb 8. These

_ta. based on chaDsJIIiDI ..... stanclaidllj will allow parlims, educaton,

. ~ .po)ieymliken, lUIll the Pb81'It1puhlic to t:rBct the

pertJniumce of every tichoOi in the riation. Data will be disanrepted 1br

stude.Dt8.by poverty .Ievele,l'IIC8, e~disa~ 8nillimited. EDglish

pro&:ieDCies to eDSure thIlt DO chiJd~ss of IUs or her baclqpound--is

~ be~.Tbe~ra1aovemmem . w ill provide ...._ _ to help states

dlieian and adminis1isr these te8ts. Stliitea . . must J'ePOrt on achool sa&ty on

asqboolby-8chool bitaia.

No Child lAIt. Be1&irId:. A 1JfIB_p . ~ 8003 9-10 (available at;

<http~;ed..IJOVJOIiiceaK>ESFJre1llre~;)ItDl1:~).

.ThlJ publication goes on to say

that, -ritle I, Part A. is inteDded to help eD8ure that

children have the opportunity

to obtain abiih-quality education and reach prolicieucy on ehaDeqiq state academic

an

II

REEXAMINING ROWLEY

561)

575

Title I. students must now make adequate yearly progress

b~ upon annual testing. ~ In fact, under NCLB, all children,

Yeg'ardleS8 .of Title 1 status,. in schools that do not make

adequate -yearly progress and are deemed in need of

improvement now have the right to attend. another public

school or receive supplemental services such as tutoring from

the SchoOl district.81

Virtuai!yevery state has DOW adQPted someform of content

and/or proficiency-stand8.rds. setting forth specific performance

etilndai'd$ andestabJishing the required outcomes for proViding

at~dents with an adequate or appropriate education under

state- law.62 . In addition, a majority of states have developed

specific .a88efJ8JDeDt measures that test students' levels of

achievem.eJlt in meeting state standards.68

There are two important .aspects of standards based reform

.related to FAPE'andtbe~upreme Court's decision in Bowley.

First, education standards establish high expectations for all

students incl-qding students With disa~. Such standards

8$5UDle an students can: a.dUeve elevated levels of learning

after setting. high expectations, clearly defining standards, and

designing. teacbiilg. to support student achievement." The

intended reBult C1t education standards is that aU students will

learn lIl0te~66 Some sta~. have even developed specific

atandutis . for students withdisabilitie8, but most simply

created-one set of standards for all -students.- The high

expeeta.tiona instate educatiOnstandards are at oddS with the

core holding in Rowley, which Stated. that scllooldistricts need

only. meet the minimaliBtic "some educational .benefit"

standard.67

The second important aspect of educationalstandards shifts

the foCus from process to outcome. Content and proficiency

.

.".

siandU'deand a8lle8&meD&8'- lrl. at 1S.

6&.20 U.S.C.

t 6311(a,) (We. 2003).

61. 2OU.S.C., 6816(b)(E), (e) (West 200S).

62; Natl. Re~Couneil. supra D. 38, at 27-29.

63. ltJ. at.27-29, 154-68.

. 64;kL llt 22-26. .29-39; Janet R. Vohs, Julia K. Landau & Carolyn A Romano,

.PElQi.lahwraOliQII. Britrf: 1ltIiBUIg ~. of ~ .8bJdg,. uIiIA I>iIIaI1ililia

t!ilIdSJmid,arda-Bo8ed Bdueufiors &fOrm (available at <ht;tp:JIwww.fcen.ortJipeed

. eselst~ib.htmt.

61$. Vahs et al,supran. 64.

M. Natl. Reaearch Council, sUj1m n. 38, at lil788; Voba, supra n. tU.

67.ROwle.Y, 468U.8. at 189, 200-01.

"

576

B.Y.U. EDUCATION AND LAW JOURNAL

[2003

standards center on whatstudents actually learn as opposed to

the process by which the students learn the infurmation. 68

Currently, special education focuses in large part on the

process of providing services to students and not neceBBarily

the outcomes that result from the services.. Education

standards redirect the inquiry to the eft'ectiveness of the

education actually provided to the student. The focus on

student. achievement contradicts Rowley's finding that the

purposeof the IDEA is to provide access to education and not

to add.reBB the substance or quality of services students ~ive

once they. have acoeBB.89

The state-estabJished Curriculum Framewotks in New

Hampshire illustrate. one example of content and proficiency

standards.70 The FraIneworks set content and proficiency

standards in various academic areas. In the area of Language

Arts, the .Framework sets forth the following general reading

standard:

.Students will deJllonstrate the in~rest and ability to

read age-appropriate .materials fluently,

with

understanding and appreciation..

The .Language Arts framework then sets forth the fullowing

broad goals:

Students will readtluently, with understanding

and appreciation.

Students. will write effectively. for a variety of

purposes and audiences.

Students

will

articulately.

speak

purposefully

and

Students will listen and view attentively and

critically.

Students will understand, appreciate, interpret,

and critically analyze claBBicaland contemporary

American and British literature as well as

literary works translated into English.

88. NatI. Reeearch CoUDDil, tmpra IL 83, at 36-39, 11...18; YOM, tmpra n. 64.

69. Rowley, 468 U.s. at 192.

70. The frameworb were e~hed 88 part of a New Hampehire 8tatute, N.H.

Rev. Stat. Ann. fl98-C (1999). The frameworb are available on the New Hampahire

of

Education

Website

at

<bttp:/Iwww.ed.lltate.nh.U8I

Department

CurriculumFrameworkaleurricuLbtm>.

REEXAMINING ROWLEY

561]

577

Students will use reading, writing, speaking,

listening, and viewing to:

gather and organize information;

communicateeffectively; and

succeed in educational, occupational,

civiC; social, and everyday settings.

While these requirements may .appear ratherbaBic at first, this

peteepmnchanges when applied to a student with a disability.

These.. goals become sigeiDcant and require scl1oo1 districts to

provide services .10 enable the&tudent to meet these goals; this

will likely be a significant change for some school districts and

'8tud~nts. For example, requiring a student with dyslexia to

read age appropriate materials fluently is a goal that some

scltoo1districts might ordinarily . not set because of the

dJ.ffieultiea a student with dyslexia often has reading.71

lliBtead, a achool district might set a goal targeting simple

itDpmvements to the student's readiPg ability, even if that

i~plOVernent left the student several years .behind in hislher

reacting level

Incorporating state educational content and proficiency

standards into the statutory definition ofFAPE means high

e~tions must now be included. in disabled students' IEPs.

Edueational standards define performancecrlteria forstuderits

that .scllool dietriet8 and parents lIJ.ust use when developing

goals:. altd objeetiVes in &. student's IEP. School districts,

paren,ts, and. courts may.. ~ use these standards when

asseeaingwhet:lter.a sc1)oo1 district bas successfully provided a

student a F APE.72

7 L stanley S. Herr, Special Edwotioll Law a,.d CIJildren. wirh Reading cmd

Other DisObiliries, 28J.L. & Educ. 3S7, 343 (1999).

72. Tbeleis 4- p<*ntial risk of using hiP 8taDdards to the detriment of lOme

studen.with disalriJiAee. For e_pJe, reqairiag a atl1deut with a diMbilliy to palllJ a

high

in order to receive a hiP JICIIool ctipJoilaa can be a JIIlQor ob8t8cle to the

~iltheet1identcaaaot n!8d d,. to their dilIability. For a diiCuasion of high

stabe. ~imd

With disabili1:ietJ, see Paul T. O'Neill, Special Educaliorl

rwtliJ8A $to1rea Tt!llWclrl' lliiI'" ~. arudUatiot&: Aa AlIalysi8 0{ CunYmt Law aIId

Polir:y, lOJ.L,; " Ed.uc. 1M, 186(2001); R&'an R. W-, StuditDt Author, The Falloc:I

Be!Wsdll1CTeaili!d~: Bow DieolJled SCuden.ts' ~ Bi,gh&8 Hove

&iim ~ bJ (J RuA ItJI1fI/1Ie1M,"~Staktt6Emma, 2002 B.Y.U. Educ. If

LAt Ml (2002); 1'heeePIObJema.ml1lt be addnlseed 80 that.menu with di.biJme8

are not pllDiabed Or a-eed baMld. upOn ~ir disability. Raising the expectatiou JDr

siudentll W;i:thdiaabili&iee must iDcIade raisiDg the expectatioI18 fin' how we teach and

how we _atudentS with dillabilitiee.

.tabs.

Biu"

578

B.Y.U. EDUCATION AND LAW JOURNAL

C.

[2003

The 1991Amendments to tMIDEA.

Congress amended the IDEA in 1997. The amendments

show . Congress' conscious decision to incorporate state

educational standards into special educational programming

for students. The statute now explicitJymsndates that states

establish performance goals. for clrildren with disabilities that

are consistent with other .goals and standards set for all

children. 78 .The 'IDEA now ,requires. states. to establish

perrol'Dl8nC2 indicators that assess progress toward achieving

those goals. At a minimum, the goals must address the

performance of children with disabilities on assessments, drop

out rates, andgracluation rates. 74

The amendments to the IDEA mark a significant change of

direction from the Court's .decision in Rowley.

The

amendments establish high expeeta~ns. for children with

disabilities to achieve real educatj()nal results.

The

amendIQents,cbange the focus of IDEA frQm one that merely

provides students.. with disabilities aooeseto .an education to

onerequiringUnproved results and achievement. The changes

&remade explicit in the House Committee Report whieh states:

This CoJlllPittee believes that the ~ issu,enow is to

place greater emphasis on improving student

performance and ensuring that children with

~bilities receive

a quality pui)lic education.

Educatio~ adri.evement f9r cbildren with ~bilities,

while improViDg, is sti)lless,than sati.ctory.... This

review and authorization althe IDEA is needed to move

to the nen step. of .provicljng. special education and

related services to cbildren with 'diaabUities: .to improve

alid increase their educational achievement.7&

Similarly, the findings section of the 19997 IDEA

amendments states that:

Over 20 years of research and experience has

demOD8trated that the education of children with

disabilities can be. made more effective by having high

expectations fOr sud1 cbildr$ and ensuring their access

in the generalctll'l'iCmumto the maximum extent

possible ...[and] 8UppOIting. bigh-quaJity, intensive

73.20 U.S.C. f 1412(&)(16) (W~t 2002).

74. Id.

75. H.R. Rpt. 1~96, at 88-84 (May 1B, 1987).

II

561]

REEXAMINING ROWLEY

579

pl'Ofeesional .development for all personnel who work

with such children in order to ensure that they have the

skills and knowJ.e4ge necessary to enable them to meet

developJ:nental goals. and, to the maximum extent

posSible, those challenging expectations that have been

established for all children." 76

Whenever possible a general curriculwnmust now include

students with disabilities, and IEPs must contain goals and

objectives that enable disabled students' involvement and

ptQgl'ess in the general curriculum that is avaiIableto all

students. 77 This is one method of incorporating the high

e~tioDSof educatiouaIstandards into special education

ptogt8ttlming tOr studeni;$ with disabilities. 'l8 The IEP details

the . sPecual educationservioos schools must provide disabled

students. The definition of special education in the IDEA now

expressly .states thatspeciai education means specially

~ instruction to ensure access to the general curriculum

S(J that thestucieBt can meet "the educational standards within

the ~ n .of the public agency that apply to all

children."79

States and school districts must now include disabled

students in their assessments or provide them with an

altel'Date examination.so

These asse88lDents commonly

measure the extent to which the student.meets the content or

ptoficlency .standards. States and districts JDust consider the

stUdent'spel'formanceon thesea$1essments when developing

78. 20 U.S.C.A. 14OO(e)(~)(A), (E)(i) (West 2002).

71.84 C.F.a.I800841(Z)(.i) (2002).

78. H.R.R9.t.l~915, ai;tI9-100. 20 U.s.CA 11461(a)(5), (a)(8)(A), (a)(8)(B) (West

2002).('1i'~aiId ~fo Part A <National.Acti:ritiea to Impruve EducatioD of

~ withDNbiJitieB) of PlEA.). See o.lIo

.s.CA t14lO(c)(6)(A).

79. S4C;F.ll f ~")(3)(ij)(JOO2).

80... Appro'-tely baJlof all Il&udeDtB with diaabilities are currently excluded

boia .welliId di8tril:t-wide .iie_IReD_The. new 19fT1 amendmeDt8 &0 the IDEA

~llVrequin:

(1) fl'Ibe.develOpment of &t:a1l!. perlimniuice lJ08la for ehiJdJ:eD with diabiJjtjee.

~tmust~certaiIl by~oftbe1lQllll8IIJ ofeducatioMl eftbrtB

.~r tbUeCbiJdren-4DcludiDg, ata 1IliDJmum, pBrimIuiDce OD aelsllme"',

dropout rates,. aM pilduatioD rates, IUId regWar teporta to tile public on

p~mward. ~ . the goals; (2) that cltiJcbeD with disabilitiea be

mc)udedin .ieDeraI IItate 8Dd~ . I I B I _ I.... with apptopria&e

acmmmodatioDe.ifnecfIBaryf;] Bod (3) that flChocJIa report to pmeDts OD tIbe

pzQgre88 of the diilabJed child as ofteD 8uuch reportS are provided to panm.ts

zo u

of~bWcIUIdnm.

See 62 Felt Reg. MO. 530.29 (Oct. 22, 1997).

580

B.Y.U. EDUCATION AND LAW JOURNAL

[2003

the student's IEP. States and districts may also ueethese

results to measure student progress towards meeting IEP goals

and objectives.81 Results on some of these tests indicate that

programming for students with disabilities is not yet aligned to

state edueational standards.

New Hampshire's test results, show vast differences

between students 'with .disabilities and students without

disabilities. New- Hampshire divides its test scores into four

categories: novioo, basic. proficient, .lUld advanced. During the

test administered. in 2000, only thirty-two percent of students

with disabilities scored basic and above in third grade language

arts, compared to eighty-three percent for all other students~

Moreover, only five percent ofstudents with disabilities scored

proficient and abov-ein third grade Iangu,agearts compared to

forty~three percent of all other students. Overall, only twenty

five .percent.of students with disabilities scored basic and above

compared to eeventypercent of all. other students. Only four

percent of students with disabilities scored proficient and above

compared to thirty.;one percent of all other students. 82

The 1997 amendments to the IDEA incorporate the high

expectations of state educational standards . into the

prognmming fur disabled students. The amendments also

show that FAPE is now' more than access. to abasictloor of

opportunity. FAPEis now aligned with the high expectations

in state education standards. .As a result, theeehigb

expe<:tationsmustbeincorporated into the IEPs' of students

with disabilities.

IV. How oro INCORPORATE HIGH STANDARDS INro IEPs

A student's unique needs and abilities determine how

educators incorporate standards into an IEP~ As a general

matter, a student's IEP Team must alJ8888 the student's needs

and abilities and then determine the best method of

incorporating

specific

standards

in

the

student's

programming.88

With respect to academics, a student's IEP need only

81. 84 C.F.R.1800.846(a)(1) (2002).

82. Sell New Hampshire Eduoational ImproveJM1lt a1&d Aae8Bmenc Program

.EducaUon., ABseU~ &port. (2001) (available at <l!tqI:/lwWW.ed.8tate.nb.QIl/

Aalle88mentlreeulta2000.htm.

83. 84 C.F.R. II 800.340 800.360 (2002).

II

561)

REEXAMINING ROWLEY

581

address thoseareas where the student's disability affects their

ability. to progress in general ClUriculwn. 84 Therefore, the IEP

does not ~esarily need to address every edueation standard

in every academic area.85 Rather, an IEP Team should assess

how the student's disability impacts hisIher ability to

participate in and progress. in the general curriculum, and

ident1fythe content andproficieney standards that apply to the

itnpacted Metis. In some cases, the content and proficiency

standards may be used directly as a goal or an objective in an

IEP. In other cases, the IEP team may need to modify content

Of. proficiency standards- by individualizing the standard and

pn;>Viding more detail on what the student will accomplish in a

period oftime. 86

The Team may also determine that the student cannot

presently meet a content orpNficiency standard and choose to

devel'OP. its own standard as an immediate goal or objeetive. 87

84, 34C.F.R. at 1800.lU7; AppeJJdi:i A to 34 C.F.R. PIIl't 800, Queetioos 2, 4.

must, lioweller, addrel8 mote than just academic Deed8. . LeM, 998

F.2dIlt: 1089.

.

86... ~ Ap~ Ato 84 C.F.R.Putaoo, Queatioaa 2, 4. The Houe Comaittee

report on tbareautlaorisation ol~IDEA states:

. ~ DeW8@basiaoapartil;ipatirmiD the pneral education curricalum is not

in.DiIIed by tile ComJDiUlee to. NiPlkin DUQor ~ in the . . 01 tile

IEP af.OO"- 01 paaiea 01 cIetaiJed .... and benchmarb or objectives in

every cuftiicuIu eoDtebt iirnMiiPli or skill. TM DeW fbcaa ill intended to

prod~""Dtothe~os8Dd ad,juataelda necel..ry tbr

cliMbled. eI1iIdreD to ~ tbepaeral flClucatiOn cUrricuJ:aia and the special

lI8rn:.e.wbich may.be. JIIlClflIIIIllr fino Ml'OIUiate J)III'ticipldiou inpartlcular

~ of the c:urricalum; Ii.. to the Ji$lre oIb diBabiJity. Specific day to d8,y

adj1l8tmelltJJ in iD8tnactioaal medlodB and approacbee that are DWIe by

either a ftPlar or epecial eduea~Dteaeber to ..... a diBabJed child to

~ve bilOJ:bel' ammar ..... wo1dd IIOi DOnDaDy require action by the

dWd's IEPTeam. BOwvver. ifchaDaea are coatemplatecl in the clWd'a

,....~ amwal . . . . __DCm.ub. or ahorttena objectiyea, or in qy af

~. eerviC88or. JIl'QIi'aIa ~ or other COJIIPOD8aU ~ in the

chiJdi8 lEP. the LEA . . . e _ t h a t the ~11BP Team is teeOD98aed in

it timely ~.r to addre. those chluJao8a.

H;R.ilpt. 1~, at 100.

.86.'. NatL llBeearcll Council. supro n. 33, at 140-11U.

81.. The juue of w!leUlel'.dae 8tudent is c:apdle. of Ittajniag ci!rbdn 8taDdarde at

oertsin srade levels iI ODe tbat:w:ill bave to be eateftdJ,y iEBlsedfbl' each 8tDdeDt. In

8O~", the etudent'I~Dt 1IUlY" 80 simtre tlIat the p!OficieDcy standard ill

um:ea:J:ilWC. ~r, dJejee ~D8 wil1libly be rare. Re8eIm:h hIlII delllOlllltrated

that ~nwith~ireeilpable oIattaiDiq hiP JeamiiItr ~ wben

.. theyan,;P1'Wid8d Wiih ~.~tbatenahJe tbem to do BO. ThiI is true e98ft

'td~eu..tJi~uit.lltbai a ~ l.Jf kwracaaetDic achievelDeJlt. John Bruer, Sc1toolB for

~: 'l'l-7S(M:.... lDit.ofTech. Preea 1992); SaDy E.S~ D:18laia, 273 Sci.

Am. 98. 10$ (NOv. 1998).

Sdlool~

"

582

B.Y.U. EDUCATION AND LAW JOURNAL

[2003

When this is done, the IEP Team's standard should be linked

with the state content or proficiency standard. The standard

developed for the student should be challenging yet achievable,

and. designed to assist the student with ultimately meeting

overall state .standards. 88

Similarly, the IEPTeam must focus on developing the

student's access skills needed to satisfy the content and

proficiency standards.~ Direct services and remediation (such

as one-on-one tutoring in Orton-Gillingham or Lindamood Bell,

etc.) are often neceBBary to help students with certain

disabilities develop the access .skUls necessary to fulfill content

and proD.e2ency standards.. The Team must develop additional

goals and objectives for these access skills. The IEP Team

must also determine if any other accommodations or

modifications are required to ellllble the student to meet the

relevant content and proficiency standards and to enable the

student's participation in state or distnct.888essments.90

88. The ComJDi:tt;ee O1lGoaJs 2000 and the Inclusion 01 Students with Disabilities

made a number of recommeDdations regarding BtudentB with disabilities and

standarda iDcludiDr the iillowing:

1. States and

that decide to implement Btandardll-based retbrma

should deaip their common content ~8, per.lb.mumce standards, and

&88888ments to maximize participation oIstudentB with disabilities.

2. . The pftlSumption. should be thatesch student with a disability will

participate. in the state or Jocail lltaDdard&; however, participation fur any

given 8tQdent may require alterations to the common standards and

8SlMlssments. Decisions to make such alterations must have compelling

educational jUlJtiftcation and must be made on an individual buie.

S, When content and pertbrmance standards or alll88SlD8nts are altered tor

a student with a disability:

the altemate standards should be chalJeDIiDI yetpotentiaJ)y

achievable;

they should re11ect the full rllDP 01 kDowJedge and akillB that

the student needs to Iiveaful1, productive lite; and

the echool system should; intbrm parents and the student of

any coDsequences oftllese alterations.

4. A88ee8lD8nt accommodations should be provided, but they 8hould be used

only to oft'set the imPact of disabilities unrelated to the kDowJedp and skiils

beq measared. T.b8yal8o. sbould be justified 9D a qee..by-cue basis, but

individual decisions abould be guidea bya unitorm set of ~

Natl. Research CoUDCil,.rtpro n. 88, at 197-209.

89. Aoce88 skill,1Ul8 _ply akilJathat are aliped with the content and

proficiency standar:da ~ .. that enable the student to meet these standarda. See

Patricia Burwell .t: Sar~ Ksooedy, ~GtJts TetlI8d, Gels '1'cJlJ6/at; m.o. Gets 1'esl8d,

Gets Tou.gla: Curriculum I'romework1JfnielOplMl&lProcess (Mid-8. Reg]. Resource Ctr.

1998) (available at b#p:i1wWw JhdLuky.edUlMSRRClPublicationslWhatjpttB.htm.

90. 34 C.F.R. at I 300.847.

JocaIii.,.

REEXAMINING ROWLEY

561)

583

Consider, for instance. athirdgrade student with dyslexia

who is having difficulty reading. The IEP Team should assess

how the dy81exia affects .the student's. involvement and

progress iii ~eeting the content and proficiency standards that

are part of the general curriculum. In New Hampshire, the

IEPTeam would need to review the state's Curriculum

F~meworks in Language 1\rtS.. that . set forth grade specifi.c

ben.cbD1arks that students.should meet. The Frameworks state

that by the end of the third grade. students should be able to:

. Determine the pronunciation and meaning of

worda by using. phonics (matching letters and

cmnbinations of letters with sounds), semantics

.(language sense and. meaning), syntactics

.(sentence structure), graphics, pictures, and

contextaal well as knowledge of roots, prefixes,

and suffixes.

.Understand and use the format and conventions

of written .language to help them read texts (for

example, left to right, top to bottom. typeface).

Identify a specific purpose for their reading such

as learning, locating information, or enjoyment.

.. :Forman initial understanding. of stories and

other materials they. 'read by identifying major

elements presented in the text including

chamcten,. setting, oonflict and. resolution. plot,

theme, main idea, and supporting details..

Reread to confirmtheir initial understanding of

a text and to extknd their initial impressions,

developing a mOl'ecomplete un~rstanding and

interpretation of the text.

.

Identify and understand the UfJe of. simple

l.an.g-eulge

including

similes,

figurative

metaphors, and idioms.

Reoognize that .their knowledge and experiences

affect their undel'8tanding of materials they

read.

. Make and confirm simple predictions to increase

their level of understanding.

II

584

B.Y.U. EDUCATION AND LAW JOURNAL

[2003

. Seek help to clarify and understand information

gathered through reading.

Employ techniques, such as previewing a text

and skimming, to aid in the selection of books

and articles to read.

Demonstrate the ability and interest to read

independently

for . le8.rning, .information,

communication, and pleasure. 9~

The Te~ should oonduct the necessary evaluations to

determine which of these standards: are impacted by the

student's dysle~and if the student can meet any of these

standards. The Team sholildthen consider how to develop a

programtbat enables the student to meet the' unmet

standards. The Teamtnay iDclude some of the unmet

standards themselves as goals and objectives in the student's

IEP, or it may . need to modify and individualize those

standards depending on the student's unique needs. The team

may also need to develop linlringstandards aliped with the

unmet standards in the curriculUlll frameworks. Goals and

objectives'thilt develop aooessskills will also need to be part of

the student's IEP.. The Team should then consider standards

for other .academic areas such as math, science, and social

studies in determining if the student's dyslexia will inhibit his

or her ability to meet these sUm~. If so, the Team should

follow the same process fur developing goals and objectives to

address the issues.

V.

CONCLUSION

The 1997 reauthorization ofthe IDEA and the eDlergence of

state educational standards and constitutional requirements

should lead to fundamental changes in how IEPs are written,

implemented, and evaluated. . This,in turn, should also

influence how oourts assess FAPE. .These changes require a

reexamination of Rowley and its "some educational benefit"

standard.

Reexamining Rowley is no small undertaking. It has

provided the basic framework for special education services for

91. LaneuaIle Ares Framework

CurriculumFrameworblcurricuLhtm.

(available

at

<http://www.ed.8tate.nh.uaI

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Codex Omnibus PDFDocumento194 pagineCodex Omnibus PDFPowhatan Vanhugh Belton100% (1)

- Manuale - I Vampiri Dell'est - I 1000 Inferni PDFDocumento109 pagineManuale - I Vampiri Dell'est - I 1000 Inferni PDFzulgaNessuna valutazione finora

- Exalted Vs World of Darkness Companion PDFDocumento98 pagineExalted Vs World of Darkness Companion PDFPowhatan Vanhugh Belton100% (3)

- Torts OutlineDocumento5 pagineTorts OutlinePowhatan Vanhugh BeltonNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 1: The Concept of PropertyDocumento52 pagineChapter 1: The Concept of PropertyPowhatan Vanhugh BeltonNessuna valutazione finora

- The Complete Vivimancer PDFDocumento90 pagineThe Complete Vivimancer PDFPowhatan Vanhugh Belton100% (1)

- #7PJ1 (& Posted)Documento8 pagine#7PJ1 (& Posted)Powhatan Vanhugh BeltonNessuna valutazione finora

- Sorcerously Advanced Alpha PDFDocumento113 pagineSorcerously Advanced Alpha PDFPowhatan Vanhugh BeltonNessuna valutazione finora

- From The VatsDocumento54 pagineFrom The VatsFoxtrot Oscar100% (2)

- Drp2732 Medic FullDocumento14 pagineDrp2732 Medic FullPowhatan Vanhugh Belton100% (1)

- Anima Beyond Fantasy - Dominus Exxet - The Dominion of KiDocumento144 pagineAnima Beyond Fantasy - Dominus Exxet - The Dominion of KijlnederNessuna valutazione finora

- Tyranid Character Guide (6!22!17)Documento68 pagineTyranid Character Guide (6!22!17)Whauknosrong67% (3)

- Masters of The Art PDFDocumento90 pagineMasters of The Art PDFPowhatan Vanhugh BeltonNessuna valutazione finora

- Demonologist Base Class LinkedDocumento59 pagineDemonologist Base Class LinkedPowhatan Vanhugh Belton100% (3)

- The Complete Vivimancer PDFDocumento90 pagineThe Complete Vivimancer PDFPowhatan Vanhugh Belton100% (1)

- Sufficiently Advanced - Ultra Tech - RPGDocumento186 pagineSufficiently Advanced - Ultra Tech - RPGblackjack2700% (1)

- Unlikely FloweringsDocumento115 pagineUnlikely FloweringsPowhatan Vanhugh BeltonNessuna valutazione finora

- Learning About Fiction and NonfictionDocumento1 paginaLearning About Fiction and NonfictionPowhatan Vanhugh BeltonNessuna valutazione finora

- D&D 3rd ed.-DragonMech-Steam Warriors PDFDocumento127 pagineD&D 3rd ed.-DragonMech-Steam Warriors PDFPowhatan Vanhugh Belton100% (2)

- Data Overview - Rural Carr Assoc-Srv Reg Rte - Crystal Springs Ms Nc10116560Documento4 pagineData Overview - Rural Carr Assoc-Srv Reg Rte - Crystal Springs Ms Nc10116560Powhatan Vanhugh BeltonNessuna valutazione finora

- Book of The Archon Scrolls of Nicodemus (10647666)Documento53 pagineBook of The Archon Scrolls of Nicodemus (10647666)Powhatan Vanhugh BeltonNessuna valutazione finora

- The Story of Treasure (5991030)Documento51 pagineThe Story of Treasure (5991030)Powhatan Vanhugh Belton100% (1)

- Book of The Archon Scrolls of Nicodemus (10647666)Documento53 pagineBook of The Archon Scrolls of Nicodemus (10647666)Powhatan Vanhugh BeltonNessuna valutazione finora

- 21 ResponsibilitiesDocumento6 pagine21 ResponsibilitiesPowhatan Vanhugh BeltonNessuna valutazione finora

- Eating Bugs Is NaturalDocumento3 pagineEating Bugs Is NaturalPowhatan Vanhugh BeltonNessuna valutazione finora

- Reexamining Rowley PDFDocumento24 pagineReexamining Rowley PDFPowhatan Vanhugh BeltonNessuna valutazione finora

- SchoolBudgetBriefFINAL PDFDocumento15 pagineSchoolBudgetBriefFINAL PDFPowhatan Vanhugh BeltonNessuna valutazione finora

- Multiple Choice QuestionsDocumento4 pagineMultiple Choice QuestionsPowhatan Vanhugh BeltonNessuna valutazione finora

- Theme WorksheetDocumento2 pagineTheme Worksheetapi-265678639Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Heirs of Delfin Vs National Housing AuthorityDocumento12 pagineHeirs of Delfin Vs National Housing AuthorityAlvin AlagdonNessuna valutazione finora

- SCHOOL PERFORMANCE - October 2013 Customs Broker Board Exam Results, TopnotchersDocumento3 pagineSCHOOL PERFORMANCE - October 2013 Customs Broker Board Exam Results, TopnotchersScoopBoyNessuna valutazione finora

- Template Peserta Angkatan 56 Gel VIIDocumento37 pagineTemplate Peserta Angkatan 56 Gel VIIfiks bandungNessuna valutazione finora

- Quiz 1 - PSW135 Game Theory in The Social Sciences PDFDocumento3 pagineQuiz 1 - PSW135 Game Theory in The Social Sciences PDFFanzil FerozNessuna valutazione finora

- T T 252161 ks1 Queen Elizabeth II Differentiated Reading Comprehension ActivityDocumento10 pagineT T 252161 ks1 Queen Elizabeth II Differentiated Reading Comprehension ActivityEmma HutchinsonNessuna valutazione finora

- Law of Delict 3703Documento19 pagineLaw of Delict 3703Vertozil BezuidenhoudtNessuna valutazione finora

- Twitter OrderDocumento34 pagineTwitter OrderTroy Matthews100% (2)

- SA - KYC Document ListDocumento1 paginaSA - KYC Document Listvulgar duskNessuna valutazione finora

- Lies, Lies, Lies (Time Magazine)Documento7 pagineLies, Lies, Lies (Time Magazine)KAWNessuna valutazione finora

- Age of EnlightenmentDocumento9 pagineAge of EnlightenmentEmpire100Nessuna valutazione finora

- Eur 1 Form PDFDocumento2 pagineEur 1 Form PDFKimberlyNessuna valutazione finora

- Electricity1303 PDFDocumento15 pagineElectricity1303 PDFElectrical Trades Union QLD & NTNessuna valutazione finora

- Nicolas-Lewis v. COMELEC (August 14, 2019)Documento8 pagineNicolas-Lewis v. COMELEC (August 14, 2019)Nichole LusticaNessuna valutazione finora

- Kamal Kumar Arya, PARTICIPATION IN DEMOCRACY: IN SEARCH OF LEGITIMACY OF PARAGRAPH 2 (1) (B) OF TENTH SCHEDULE OF THE CONSTITUTIONDocumento28 pagineKamal Kumar Arya, PARTICIPATION IN DEMOCRACY: IN SEARCH OF LEGITIMACY OF PARAGRAPH 2 (1) (B) OF TENTH SCHEDULE OF THE CONSTITUTIONNikhil RanjanNessuna valutazione finora

- Tharcisse Renzaho Judgement and SentenceDocumento235 pagineTharcisse Renzaho Judgement and SentenceKagatama100% (1)

- Understanding Public PolicyDocumento67 pagineUnderstanding Public PolicyRia Tiglao FortugalizaNessuna valutazione finora

- Data Ekspor Batik 2018-2021Documento166 pagineData Ekspor Batik 2018-2021nugasyukNessuna valutazione finora

- 10 French Revolution WorksheetDocumento2 pagine10 French Revolution WorksheetSarai Martinez0% (1)

- Regina Ongsiako Reyes v. Commission On ElectionsDocumento2 pagineRegina Ongsiako Reyes v. Commission On ElectionsSamuel John CahimatNessuna valutazione finora

- Policy Brief Powerpoint PresentationDocumento14 paginePolicy Brief Powerpoint PresentationKenya Dialogues Project100% (3)

- A.M. No. 11-9-4-SCDocumento2 pagineA.M. No. 11-9-4-SCJam PascasioNessuna valutazione finora

- 3 EME CentreDocumento37 pagine3 EME CentrePRAVESH RAONessuna valutazione finora

- Physical and Mental Examination of Persons: Rule 28Documento29 paginePhysical and Mental Examination of Persons: Rule 28Kareen BaucanNessuna valutazione finora

- Human Security Is An Emerging Paradigm For Understanding Global VulnerabilitiesDocumento7 pagineHuman Security Is An Emerging Paradigm For Understanding Global VulnerabilitiesOlgica StefanovskaNessuna valutazione finora

- ATF Form 4 Application For Tax Paid Transfer and Registration of FirearmDocumento12 pagineATF Form 4 Application For Tax Paid Transfer and Registration of FirearmAmmoLand Shooting Sports NewsNessuna valutazione finora

- Sources of Law UKDocumento11 pagineSources of Law UKIván Elías0% (2)

- 10 - Chapter 5Documento74 pagine10 - Chapter 5shrinivas legalNessuna valutazione finora

- Syria Under Fire Zionist Destabilization Hits Critical MassDocumento18 pagineSyria Under Fire Zionist Destabilization Hits Critical Masstrk868581Nessuna valutazione finora

- Principle of Legitimate Cooperation: Rosanna Bucag, UST SNDocumento3 paginePrinciple of Legitimate Cooperation: Rosanna Bucag, UST SNROSANNA BUCAG50% (2)

- The Concept of Social JusticeDocumento22 pagineThe Concept of Social JusticeIdrish Mohammed Raees100% (2)