Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Westlaw Document 05 35 01 LAD PDF

Caricato da

Wen SiTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Westlaw Document 05 35 01 LAD PDF

Caricato da

Wen SiCopyright:

Formati disponibili

CONSTLJ 2009, 25(2), 103-116

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY

Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116

(Cite as: Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116)

Page 1

Construction Law Journal

2009

Article

LIQUIDATED DAMAGES IN THE MALAYSIAN STANDARD FORMS OF CONSTRUCTION CONTRACT:

THE LAW AND THE PRACTICE

M.S. Mohd Danuri.

M.E. Che Munaaim.

L.C. Yen.

Copyright (c) Sweet & Maxwell Limited and Contributors

Case: Murugiah v Retnasamy

[1995] 1 M.L.J. 817 (Fed Ct (Mal))

Legislation: Contracts Act 1950 (Malaysia) s.74, s.75

Subject: CONSTRUCTION LAW. Other related subjects: Contracts

Keywords: Breach of contract; Construction contracts; Liquidated damages;

Malaysia; Standard forms of contract

Abstract: Explores the issues faced by Malaysian clients seeking to

claim liquidated damages for breach of a construction contract under

the Malaysian Contracts Act 1950 s.75, as interpreted by the Federal

Court in Murugiah v Retnasamy on the need to demonstrate actual loss

prior to an award of damages. Presents the findings of a study on the

methodology for calculating liquidated damages in the Malaysian construction industry. Comments on the liquidated damages clauses contained in a number of standard form building contracts used in Malaysia.

*103 Abstract

The rule of the recovery of liquidated damages in Malaysia is somewhat different from that of the United Kingdom, due to the strict interpretation of s.75 of

the Malaysian Contracts Act 1950 by the Federal Court in the case of Selvakumar a/

l Murugiah v Thiagarajah a/l Retnasamy, [FN1] where it was held that the party

claiming for liquidated damages needs to prove the actual loss suffered. This decision effectively defeats the purpose of including the liquidated damages clause

in the standard forms of contract, as the inclusion was meant to negate the re-

2009 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

CONSTLJ 2009, 25(2), 103-116

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY

Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116

(Cite as: Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116)

Page 2

quirement on the part of the employer to prove the actual loss suffered following

delayed completion by the contractor. As a result, cl.22 of the Malaysian Institute of Architects (PAM) 2006 was drafted to circumvent the "odd" requirement introduced in the Selvakumar case. However, to date, that clause has not been tried

and tested in the local courts. Accordingly, this article seeks to examine the issues related to problems faced by the clients when seeking liquidated damages from

the defaulting contractors and the common methods used in calculating the amount

of liquidated damages. It is hoped that this article could contribute towards understanding and overcoming some of the problems related to the enforceability of

liquidated damages, particularly in the Malaysian legal context.

*104 Introduction

At common law, liquidated damages are interpreted as a genuine pre-estimate of

loss. For instance, in the case of Clydebank Engineering and Shipbuilding Co Ltd v

Don Jose Yzquierdo & Castaneda [FN2] it has been decided that the essence of liquidated damages is a genuine covenanted pre-estimate of loss. However, Lord Dunedin, in the case of Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co Ltd v New Garage & Motor Co [FN3]

said that in the event that the amount of liquidated damages is extravagant and

unconscionable in comparison with the greatest loss that could possibly flow from

the breach, it will be regarded as a penalty and thus, unenforceable.

It is convenient to say that at common law, liquidated damages will not be enforceable if the court finds that the amount is not a genuine pre-estimate of loss

or where the sum is far greater than the client's estimated loss, which would

amount to a penalty. Moreover, and very importantly, it is the court's duty to

identify whether the amount stipulated in the contract is in truth a penalty or

liquidated damages irrespective of the terms used in the contract. It follows from

the Court's decision in the case of Public Works Commissioner v Hills [FN4] that

if the liquidated damages are held to be a penalty, the client will still be able

to recover unliquidated damages, provided they can prove their loss.

The House of Lords in Clydebank Engineering anticipated that:

"... although undoubtedly there is damage the nature of the damage is such

that proof of it is extremely complex, difficult and expensive". [FN5]

Therefore, the purpose of liquidated damages in the standard form of building contract is to simplify the process by allowing the client to deduct loss suffered

due to the contractor's delay in completing the project without the need to prove

such loss. However, the following Malaysian cases suggest that the clients may not

have the privilege of claiming liquidated damages without having to prove the actual loss suffered.

In the Malaysian legal context, the cases of Maniam v The State of Perak, [FN6]

Linggi Plantations Ltd v Jagatheesan [FN7] and a few other cases such as Larut

Matang Supermarket Sdn Bhd v Liew Fook Yung, [FN8] suggest that although s.75 of

the Contracts Act 1950 stipulated that "there is no difference between penalty and

2009 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

CONSTLJ 2009, 25(2), 103-116

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY

Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116

(Cite as: Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116)

Page 3

liquidated damages", it is still important for the liquidated damages amount to be

a genuine pre-estimate of loss. According to the case of Selvakumar a/l Murugiah v

Thiagarajah a/l Retnasamy, [FN9] even though liquidated damages are included in

the contract, the plaintiff must still prove the sum is the actual loss suffered.

Consequently, it is very important for the quantity surveyor and other construction professionals to calculate appropriately the actual loss suffered by *105 the

client in the event that there is a delay in completion. In any event, the client

must be able to prove the actual loss suffered or reasonably pre-estimate the

loss. This is to avoid the figure from being attacked or disputed by the contractor.

This article seeks to examine the issues related to problems faced by the clients when seeking liquidated damages from the defaulting contractors. This article

will also present findings on the common method of calculating liquidated damages

stipulated in the contract. It is hoped that this article could contribute towards

understanding and overcoming some of the problems related to the enforceability of

liquidated damages, particularly in the Malaysian legal context.

The study: methodology adopted

The preliminary stage of this study was an extensive literature search which

was followed by in-depth interviews with quantity surveying (QS) consultants involved in construction industry practice. The purpose was threefold: first, to

present the development of law in relation to liquidated damages in the Malaysian

construction industry; secondly, to identify the legal issues pertaining to liquidated damages; and thirdly, to identify the common method used for the calculation of liquidated damages in the Malaysian construction industry.

Liquidated damages clause in various standard forms of building contract in Malaysia

It is a common practice for the Malaysian construction industry to include liquidated damages in the standard forms of building contracts. In this regard, the

standard forms of building contract commonly used in Malaysia are the Malaysian

Institute of Architects (MIA or PAM) 1998 forms, the Public Works Department (PWD)

forms and the Institution of Engineers Malaysia (IEM) 1989 form. These forms have

been amended a few times since inception and recently the PAM and PWD forms have

been called for its amendments and have been published as the PAM2006 and

PWD203/203A (Rev.2007) forms of contract. Until now, the latest additions to the

Malaysian standard form of contract are the CIDB2000, published by the Construction Industry Development Board (CIDB). However, until now, the CIDB2000 form has

not been widely used by the Malaysian construction industry due to the prevalence

of other standard forms of contract, especially forms published by PAM and PWD and

owing to the construction players' familiarity with these two published standard

forms of contracts.

2009 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

CONSTLJ 2009, 25(2), 103-116

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY

Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116

(Cite as: Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116)

Page 4

The PAM2006 form is commonly used for private funded building projects. The

form is published by the Malaysian Institute of Architects and covers both the

main contract and nominated sub-contract based on the traditional lump sum procurement method. The main contract PAM2006 form comes in two editions, namely

"without quantities" and "with quantities" editions. Meanwhile, PWD203A (with

quantities) and PWD203 (without quantities) are standard forms of contract published by the PWD. PWD forms are mainly used for public funded projects, and applied for both building and engineering contracts.

It is worth highlighting that under both the PAM1998 and PWD203 forms of contract, the term employed is "Liquidated and Ascertained Damages". It has *106 been

stated that the word "ascertained" used in the forms of contract merely underlines

the fact that the amount indicated in the contract has been properly computed as a

"genuine pre-estimate" of the consequences of the delay. [FN10] Therefore, under

these forms of contract, the client should be able to recover the sum as liquidated and ascertained damages provided that the figure has been properly computed

or estimated. Nevertheless, the fact is that through a series of court cases related to this issue, it has to be noted that the liquidated damages amount must

reflect a reasonable amount to both parties. In this regard, it is suggested that,

in assessing the reasonableness of the amount, the client should ensure that an

appropriate method is used for the calculation of the liquidated damages to arrive

at a reasonable figure. However, in the newly published PAM2006, under cl.22.2,

the term has been amended to "Liquidated Damages" instead of "Liquidated and Ascertained Damages", as provided in the old PAM1998 form. This is mainly due to the

express provision of a "genuine pre-estimate of the loss" in the PAM2006 form, as

follows:

"The Liquidated Damages stated in the Appendix is a genuine pre-estimate of

the loss and/or damage which the Employer will suffer in the event that the

Contractor is in breach of Clause 21.0 and 22.0. The parties agree that by entering into the Contract, the Contractor shall pay to the Employer the said

amount, if the same becomes due without the need for the Employer to prove his

loss and/or damage unless the contrary is proven by the Contractor."

Meanwhile, it has been suggested that liquidated and ascertained damages serve as

a monetary amount fixed and agreed by the parties in advance, as damages payable

in the event of late completion. [FN11] This is the most common argument raised by

the clients in which they claim that the contractors should not have disputed the

liquidated damages since the amount has been agreed by both parties upon the signing of the agreement. In addition, the liquidated damages are usually provided for

by the client in the tender document during the tendering stage and, therefore,

the contractor has been made aware of the amount even before they tender for the

project. The client's suggestion is that once the contractor has been awarded a

contract, the contractor has to bear the risk of having to pay for the liquidated

damages for late completion, irrespective of the amount stipulated in the contract.

2009 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

CONSTLJ 2009, 25(2), 103-116

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY

Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116

(Cite as: Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116)

Page 5

In Malaysia, since Selvakumar a/l Murugiah v Thiagarajah a/l Retnasamy [FN12]

decided that the plaintiff needs to prove the actual loss even though the liquidated damages amount is included in the contract, there is a tendency for the contract to be drafted so as to avoid the client having difficulty in proving the

loss suffered. For instance, cl.22.2 of old PAM1998 states that:

"The Liquidated and Ascertained Damages stated in the Appendix is to be

deemed to be as the actual loss which the Employer will suffer in the event

that the Contractor is in breach of the Clause hereof. The Contractor by *107

entering into this Contract agrees to pay to the Employer the said amount(s) if

the same become due without the need of the employer to prove his actual damage

or loss."

The wording of cl.22 of PAM1998 was drafted with the hope of negating the requirement on the part of the client to prove the loss suffered once the said sum becomes due. This is to remedy the wording of the old PAM1969, which may allow the

contractor to challenge the liquidated damages as anticipated by the Federal Court

when deciding on the Selvakumar case. Nevertheless, to date, the provision of

cl.22 of PAM1998 and the newly published PAM2006 form is untried in any local

courts and therefore, it is appropriate to suggest that the effectiveness of the

provision to overcome the decision in the Selvakumar case is still in doubt.

Meanwhile, PWD203 and IEM 1989 forms are silent on the issue of whether there

is no need for the client to prove the loss suffered. Therefore, it is observed

that the provision for liquidated damages in the PWD203 and IEM 1989 forms are

more likely to be challenged by the contractors compared with the PAM2006 form.

Problems when seeking liquidated damages

The following presents some of the problems related to the recovery of liquidated damages extracted from the Malaysian case law, as well as cases from other

common law jurisdictions which may be applicable to the local scene.

Difficulty in quantifying the liquidated damages

Following the decision of the Federal Court (the highest court in Malaysia) in

Selvakumar a/l Murugiah v Thiagarajah a/l Retnasamy, [FN13] it is impossible for

the claiming party to succeed in recovering the liquidated damages without the

need to prove the actual loss suffered. If the damages are quantifiable, the onus

lies on the claiming party to prove such losses, failing which it will result in

the refusal of the court to award such damages. There is, however, an exception to

the general rule if the court finds that there is actually loss suffered but such

a loss is difficult to assess, as has been decided in the case of Chaplin v Hicks.

[FN14] For example, in the construction of commercial buildings, it is feasible to

calculate the amount of loss suffered due to late completion by the contractor as

it is assumed that the developer loans the money from a financial institution, so

it is subject to a certain percentage of interest rate. As such, any delay by the

contractor would result in an additional amount of interest fees payable to the

2009 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

CONSTLJ 2009, 25(2), 103-116

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY

Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116

(Cite as: Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116)

Page 6

bank. Any other methods of calculating the liquidated damages amount may be employed by the client before agreeing the inclusion of such an amount in the contract document, for example calculation based on loss of rent, etc.

The situation is rather different when dealing with government projects, as the

amount of damages is unquantifiable due to the fact that the Government *108 does

not normally borrow any money from financial institutions. Furthermore, a government is a non-profit organisation which provides infrastructures for the public.

For example, if a contractor delays in completing an extension of a new school

block for his government client, the latter would find it very difficult to

quantify the damages as the teachers and pupils can still continue to use the old

school block, although in reality there are some losses suffered in terms of their

hardship in learning in a very cramped room. However, the damages must not be too

remote to be recovered. It is submitted that the Government, being a noncommercial and non-profit making entity, should be entitled to recover the agreed

damages "simpliciter" as reasonable compensation, simply by reason that the damage

or loss is unlikely to be quantifiable in monetary terms. [FN15] The case of Allson International Management Ltd v LA Cemara Resort Management Sdn Bhd [FN16] offers an interesting idea. In this case, both parties had expressly agreed that the

loss was difficult to quantify; as such, in the event of termination of contract

before the opening date, the plaintiff was entitled to RM 1 million as compensation. The Court held that the plaintiff did not need to prove such compensation

although the amount was quite substantial as both parties had agreed that the damages were unquantifiable before the signing of the contract. It would be sensible

for the PWD of Malaysia to adopt this provision in order to prevent future disputes about liquidated damages.

The position of the deduction of liquidated damages in Malaysia is somewhat

different from its Commonwealth counterparts. In the case of Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre

Co Ltd v New Garage & Motor Co Ltd, [FN17] there is a distinction between penalty

and compensatory clauses in which the latter is enforceable as opposed to the

former. This is due to the purpose of damages as being compensatory in nature, in

which the aggrieved party is restored back to the position they would have been in

if the other had not breached the contract. If the clause is found to be a penalty, it will be inoperative and the liquidated damages provision will be struck

out from the contract, leaving the employer with the remedy for general damages.

Further, according to the case of BFI Group of Companies Ltd v DCB Integration

System Ltd, [FN18] under common law there is no need for the employer to prove

such a loss in terms of liquidated damages as long as the amount is a genuine preestimate of loss and the fact that the employer may not suffer any loss due to the

contractor's breach for delayed completion is irrelevant.

In Malaysia, there is no distinction between penalty and compensatory clauses

as both are dealt with in the same manner, owing to the availability of s.75 of

the Contracts Act 1950. This clause has been given a restricted interpretation by

the Federal Court in the case of Selvakumar a/l Murugiah v Thiagarajah a/l Ret-

2009 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

CONSTLJ 2009, 25(2), 103-116

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY

Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116

(Cite as: Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116)

Page 7

nasamy, [FN19] in which it imposed a duty to the party claiming for damages to

prove such a loss, failing which it will result in the refusal of the court to

award such damages. The decision in this case has defeated the whole purpose of

having liquidated damages provision in the standard forms of contract, as *109 the

inclusion was meant to negate the need for the employer to prove the actual loss

suffered in the event of the contractor's failure on timely completion. The decision in this case has been followed by a series of cases such as Lion Engineering Sdn Bhd v Pauchuan Development Sdn Bhd, [FN20] Sakinas Sdn Bhd v Siew Yik Hau

[FN21] and Joo Leong Timber Merchant v Dr Jaswant Singh a/l Jagat Singh, [FN22]

which express beyond doubt that there is a necessity for the claiming party to

prove such a loss as a consequence of the contractor's late completion. Worse

still, the liquidated damages amount is also regarded as the ceiling amount recoverable. As for the employers, it is prudent to ensure that the liquidated damages

amount stipulated in the contract is reasonable and a genuine pre-estimate of loss

and that all the calculations of liquidated damages are kept for future reference.

It may also be sensible to contract out the provision of s.75 of the Malaysian

Contracts Act 1950 as being adopted by the PAM2006 standard form of contract for

the sole purpose of preventing further disputes about the recovery of liquidated

damages by the employer.

Blank/discrepancy/nil provision

It is noteworthy that the rate of liquidated damages inserted in the contract

document must be unambiguous. It is also essential not to leave blank the liquidated damages rate section as the courts will interpret this as not in favour of

the party who is claiming the damages. It is common to find a discrepancy in liquidated damages between the appendix of the conditions of contract and the preliminaries section, the reason being that quantity surveyors tend to round up the

rate to the nearest hundred or thousand in the appendix of the conditions of contract, but maintain the old figure in the preliminaries or vice-versa.

If the rate is omitted or there is a discrepancy in the liquidated damages

amount, then the clause is inoperative, which means that the client is unable to

recover the liquidated damages. This is, however, without prejudice to the client's right to claim for general damages against the defaulting contractor under

the first limb of Hadley v Baxendale. [FN23] However, according to the case of

Temloc Ltd v Errill Properties Ltd, [FN24] if "Nil" is inserted in the liquidated

damages rate section it would have a different impact altogether as the party who

is claiming the damages may be denied the remedy either under breach of contract

or under common law.

Interestingly, cl.26.3 of CIDB2000 clearly expresses that if the client is not

entitled to recover liquidated damages for whatever reason, the client shall remain entitled to recover such loss, expense, cost and damages as the client would

be entitled to at law. In other words, the client can still claim for unliquidated

damages as provided by the law. This clause expressly preserves the client's right

2009 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

CONSTLJ 2009, 25(2), 103-116

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY

Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116

(Cite as: Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116)

Page 8

to claim for general damages in accordance with s.74 of the Contracts Act 1950,

codified from the landmark case of Hadley v Baxendale. [FN25]

*110 The limit of liability of liquidated damages clause

The law in Malaysia does not only require the plaintiff to prove his loss in

order to succeed in claiming damages, but that it must also be reasonable in accordance with the rules in Hadley v Baxendale. [FN26] Section 74 of the Contracts

Act 1950 stipulates that:

"The party who suffers loss or damage which naturally arose as a result of

the breach (the loss or damage incurred must not be too remote) caused by the

party who has broken the contract is entitled to claim for compensation from

the party who breached it."

Further, s.75 of the Contracts Act 1950 states that when a contract has been

broken, irrespective of whether there are liquidated damages or a penalty, the innocent party is entitled to receive reasonable compensation from the party who has

broken the contract. In this case, reasonable liquidated damages should amount to

a figure which arises naturally as a result of the breach and must not be too remote to be recoverable. Most of the Malaysian standard forms of contract use the

words liquidated and "ascertained" damages, which simply emphasise the requirement

for the amount to be a genuinely pre-estimated loss suffered by the clients. Perhaps the liability of the contractor towards the liquidated damages should be for

the direct damages suffered by the owner due to the delay in completion. On the

other hand, the clients should bear this in mind when determining the amount for

liquidated damages, so that they will have no difficulty in reasonably proving

their losses.

The liability to pay for liquidated damages usually arises when the contractor

fails to complete the project by or on the date for completion. However, the contract may provide that some condition precedent must be fulfilled before the client can claim for liquidated damages. In this regard, cl.22.1 of PAM1998 stipulates that the contractor becomes liable to pay for liquidated damages once the

contractor has failed to complete the works by or on the date for completion or

any extended date, and the architect has certified in writing the failure on the

contractor's part to complete the work on the agreed date. Therefore, in PAM1998,

the architect's written certification is a condition precedent before the client

can claim for liquidated damages. The same goes for the PWD form of contract, except that it specifically requires the superintending officer (SO) to issue a certificate referred to as the certificate of non-completion. In the case of Lion Engineering Sdn Bhd v Pauchuan Development Sdn Bhd, [FN27] the Court decided that,

from the plain reading of cl.22 of PAM1969, it is appropriate to say that the certificate of non-completion is a condition precedent to the deduction of liquidated

damages. This salient point has been provided in the newly published PAM2006 where

it clearly spells out that the architect shall issue a certificate of noncompletion if the contractor fails to complete the works by or on the date for

completion or any extended date. Interestingly, cl.22.1 of PAM2006 makes it clear

2009 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

CONSTLJ 2009, 25(2), 103-116

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY

Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116

(Cite as: Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116)

Page 9

that the architect shall not take into account the amount of liquidated damages

payable by the contractor to the employer in the issuance of payment certificates

and final certificate. It merely requires the employer to inform the contractor in

writing of such deduction.

*111 Section 75 of the Contracts Act 1950 specifies that liquidated damages are

recoverable by the plaintiff, but in any event the amount will be considered as

the maximum pre-estimate loss to be recovered by the employer when the contract

has been broken. This has been decided in the case of Selvakumar a/l Murugiah v

Thiagarajah a/l Retnasamy, [FN28] in which the Federal Court held that damages to

be awarded by the Court must not exceed the sum fixed in the contract for liquidated damages. This is the result of a contract which specifies the amount of liquidated damages if there is a breach of contract. However, this may not applicable in most of the construction contracts, where usually, the liquidated damages

for delay in completion is calculated by multiplying the rates of liquidated damages per day with the number of days that are late in completion.

Methods of calculating liquidated damages

There are various ways of computing the amount of liquidated damages. A widely

used one is the computation based on the loss of interest which the client has to

pay on capital which they have borrowed. Liquidated damages may also be computed

by loss of income from rent if the building is for renting upon completion. Computation of liquidated damages based on prolongation cost for overheads, site supervision, etc. can also be employed by the client. In this regard, Clark [FN29]

highlighted the importance to calculate liquidated damages properly, as follows:

"Once the owner has made decision to include a liquidated damages clause, it

must consider the type of damages to be recovered and the calculation method.

When it comes to calculating liquidated damages amounts for inclusion into particular contract, the owner must know his project and all of its interfaces."

In this regard, the PWD has its own standard practice in computing the liquidated

damages in which the base lending rate (BLR) is used as the basis for computing

the liquidated damages amount, assuming that the Government loans the capital for

the construction from financial institutions. As discussed above, the damages sustained by the Government in the event of delayed completion by the contractor are

actually unquantifiable but yet not too remote. Owing to the vulnerability of the

liquidated damages provision in the PWD standard form of contract, there is a

tendency that the contractors might contest that the Government does not suffer

any loss due to the contractor's breach for delayed completion and the failure on

the part of the Government to prove such a loss will result in the refusal by the

court to award the damages.

The fact that there is a difficulty in the Government quantifying the damages

does not prejudice its right to claim for the liquidated damages, as in this case

it falls into the exception to the first principle of the Selvakumar case as the

damages are unquantifiable in nature but not too remote to be recoverable. This

2009 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

CONSTLJ 2009, 25(2), 103-116

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY

Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116

(Cite as: Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116)

Page 10

would relieve the Government of the obligation to prove its loss as a *112 consequence of the contractor's breach for delayed completion. The method of calculation of liquidated damages for all government projects has been decided by the PWD

of Malaysia through a department circular published in April 1993. The following

example illustrates the calculation of liquidated damages for a government

project:

(a) Base lending rate = say, 10% per annum

(b) Percentages of liquidated damages =

10%

________

365 days

The percentages of LD = 0.0273% X the contract value Thus, the amount of LD per

day = MYR 2,730.00 per day (say, the contract value is 10 million)

Calculation of liquidated damages in theory

The method of calculation of liquidated damages is very problematic, since the

actual loss is usually hard to assess. In this regard, William [FN30] suggests

that the actual loss may include the following:

additional supervisorial expenses;

other additional expenses actually caused by the delay;

overhead expenses incurred during the delay period;

if the project is intended to be leased, reasonable value of loss of

use and the lost of rentals which could not have been reasonably avoided;

if the project is not intended to be leased, reasonable value of loss

of use, interest expense, and interest expense during the delay period; and

any other reasonably foreseeable damages the owner may have incurred,

including loss of profits from a business.

In addition, Dave [FN31] proposes that liquidated damages may be estimated as a

daily rate for the period of late performance based on one or more of the following:

extra maintenance, operational or utility costs in continued use of an

old or inefficient building or facility;

maintenance of a new building or facility before its beneficial use;

extra rental of other buildings because of late completion of the new

building;

interest on investment or borrowed capital of the project;

costs for extra personnel who are on standby waiting for completion;

extended supervision, inspection or engineering costs;

*113 loss of revenue, bridge tolls, sale of product, rental value of

property, etc.;

moving costs;

impact costs; and

wages/material cost increase.

2009 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

CONSTLJ 2009, 25(2), 103-116

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY

Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116

(Cite as: Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116)

Page 11

Calculation of liquidated damages in the private sector

Interviews with eight quantity surveyors (QS) were carried out for the purpose

of acquiring data on how the private sector calculates the liquidated damages

based on convenience sampling. All respondents were from eight different QS firms

and have well over five years of experience in the Malaysian construction industry. The interview findings reveal that the methods used in calculating liquidated damages in the private sector are contingent on the nature of the project,

i.e. whether the project is for sale or rent, and are also based on the types of

the project, whether it is residential, commercial or infrastructure. It should be

noted that this article will only present some of the common methods of calculating liquidated damages for residential and commercial projects. The common methods

used for calculating liquidated damages for residential and commercial projects

are as follows:

Residential projects

The methods used in calculating the liquidated damages for residential projects

can be categorised into two common methods. Basically, most of the methods used by

the firms are based on the damages for late delivery of vacant possession stipulated in the sale and purchase agreement (SPA). The calculation of liquidated damages in this context is a sum chargeable to the contractor by the client in the

event that the contractor fails to complete the project by the date for completion

stipulated in the contract. Nevertheless, the methods should be used as a guide

only and should be used strictly after all considerations have been made with regard to:

the characteristics of the project;

the clients' risk; and

ensuring that the damages are not too remote to be recoverable

(commonly referred to as "direct damages" or have been in the contemplation

of both parties at the time they made the contract as the probable result of

the breach (commonly referred to as "consequential losses") as provided by

s.74 of the Contracts Act 1950.

Method No. 1:

LD/day=

10% selling prices + 2% to 3% administrative charges

____________________________________________________

365 days

According to the SPA, if the developer fails to deliver the vacant possession of

the building as stipulated in the SPA, the developer must pay for damages *114

calculated on a daily basis, 10 per cent per annum of the purchase price. Therefore, 10 per cent of the selling price is the actual loss suffered by the developer if the contractor cannot complete within the completion period. This means

2009 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

CONSTLJ 2009, 25(2), 103-116

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY

Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116

(Cite as: Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116)

Page 12

that the developer will claim liquidated damages which is equal to 10 per cent of

the selling price plus two to three per cent of the administrative cost, divided

by 365 days. It has to be noted that the amount of liquidated damages is calculated based on one unit of building and must be multiplied by the number of units

of buildings that are late in completion. Out of the eight QS firms, five who are

actively involved within residential projects use this method in the calculation

of liquidated damages for their clients.

Method No. 2:

LD/day =

Gross revenue + finance charges

_______________________________

365 days

+ Administrative fee

This formula considers the client's loss of gross revenue and finance charges

with the assumptions that the residential project is sold based on the build and

sell concept. It is suggested that the gross revenue will normally include the

design cost, construction cost, land cost and profit. The finance charges, on the

other hand, will be based on the total amount of interest chargeable by the financial institution from the capital cost borrowed, while the administrative fee is

normally 10 per cent.

Commercial projects

Fundamentally, the method used in calculating liquidated damages for commercial

projects will normally take into consideration the nature of the project: whether

the project is for rent or sale. For instance, if the project is for sale, then

Method No. 1, as above, may be used for calculating the liquidated damages. Normally, for commercial projects such as shopping complexes and hypermarket buildings, the shop lots are usually offered for rent. Thus, for example, if the

project is a two-storey shopping complex, then the liquidated damages can be based

on the loss of rental of the shop lots.

Before determining the liquidated damages amount, the gross floor area (GFA)

should be measured and then deducted with the circulation and services area in order to obtain the net rentable area (NRA). In addition, a reasonable assumption of

the rentable rate per square foot (SF) per month must also be made. The following

example shows the calculation of liquidated damages for a shopping complex:

a) Gross floor area = 300,000.00 SF

b) Circulation and services = 25,000.00 SF

c) Net rentable area = 275,000.00 SF

d) Rental rate assumed at MYR 3.00 per SF per month

e) Total rental price = 275,000.00 SF x RM3.00/SF = RM 825,000.00

2009 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

CONSTLJ 2009, 25(2), 103-116

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY

Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116

(Cite as: Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116)

f) LD

Page 13

MYR825,000.00

________________________

30 days

= MYR 27,500.00 per day.

*115 The calculation of liquidated damages which is based on the loss of rental as

above may be challenged by the contractor in response to the Selvakumar case. For

instance, the contractor may challenge on the basis that the lost of rental fails

to recognise the fact that the estimation of loss is merely based on an estimation

that 100 per cent of the rentable area will be taken up by the tenant. Problems

may exist if the contractor feels that the amount of liquidated damages is too extravagant and unreasonable, i.e. MYR 27,500.00 per day. The contractor may challenge the liquidated damages if the rentable area taken up by the businesses is in

fact amounted to only 80 per cent of the rentable area. In the light of this argument and subject to the fact and circumstances of the case, it may give the contractor a legitimate claim to challenge the reasonableness of the liquidated damages amount.

One important point to highlight is that all the interviewees agreed that the

liquidated damages amount must be reasonable to reflect the actual or preestimate

of loss. However, based on the interviews, they reported that most of the clients

or consultants do not clarify the derivation of the liquidated damages amount to

the contractors. When asked further, the argument is that the contractors themselves never ask how the client derives the amount and the condition of contract

or the appendix of contract form itself does not require the disclosure of the

method to be made. This is understandable, since the contractor does not usually

want to be viewed negatively by the client by asking something which is considered

sensitive to the client, with the hope of establishing good and pleasant longstanding business relationships. In this regard, cl.22.2 of PAM2006 provides the

room for the contractor to challenge the liquidated damages amount stated in the

contract. It stipulates that the contractor shall agree to pay the liquidated damages amount as a genuine pre-estimate of the loss without the need for the employer to prove its loss unless the contrary is proven by the contractor. In the light

of this provision, it is a daunting task for the contractor to challenge the liquidated damages amount, if the basis for deriving at the liquidated damages

amount is not made available to the contractor. Thus, it is essential for the clients or consultants to clarify the derivation of the liquidated damages amount to

the contractors as to ensure the efficacy of such provision.

Conclusion

Clients in both public and private sectors are advised to formulate a genuine

pre-estimate of the likely loss and it is prudent to make known the method of calculation of liquidated damages to the contractors. The disclosure of the method of

calculation will promote the reasonableness of liquidated damages amount since the

client will be required to have some sort of formula for deriving the amount. This

2009 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

CONSTLJ 2009, 25(2), 103-116

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY

Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116

(Cite as: Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116)

Page 14

would avoid a ground of evidentiary value in any subsequent court proceedings if

the contractors were to challenge the stipulated amount as an unreasonable, extravagant and unconscionable amount, in comparison with the real loss suffered by the

clients. As shown by the relevant case law and the Contracts Act 1950, liquidated

damages is enforceable only if it represents a genuine pre-estimate of the loss

caused by late completion. It has to be noted that, in the Malaysian context, compensation is apparently recoverable up to the limit of the stipulated figure which

is proven as a genuine pre-estimate and is considered by the courts to be reasonable. The research finding seems to suggest that the way some of the Malaysian

construction industry players *116 behave towards the issue of reasonableness of

the liquidated damages amount may not correspond with the development of the law.

Although it may not be enough to generalise the findings owing to the small number

of interviewees in this study, it is appropriate to say that the QS views with regard to this issue are respectable since the questioning was not specifically referring to any project in which they had been involved. Thus, it is suggested that

the method of calculating the liquidated damages by the clients or consultants

should be made more transparent and turn out to be the most reasonable amount to

both parties. This recommendation is to make it possible for the employers to

prove their actual loss or damages when disputes arise and consequently to circumvent the liquidated damages from being challenged by the contractor. It is anticipated that ideally, the contractor must know exactly what the client's loss is,

so that they can appreciate the extent of risk demonstrated by the liquidated damages clause and use it as a mechanism to mitigate the delay. Finally, it is recommended that this study could be improved further in the field by increasing the

number of interviews or by using a postal survey to a broader spectrum of professionals in the industry.

FN Centre for Project and Facilities Management, Faculty of the Built Environment,

University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Email: msuhaimi @um.edu.my;

yenn0208@yahoo.com.

FN Centre for Project and Facilities Management, Faculty of the Built Environment,

University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Email: ehsan@um.edu.my and Centre of Construction Law and Dispute Resolution, The Old Watch House, King's College London,

Strand Campus, Strand, London WC2R 2LS, Email: muhammad.che munaaim@kcl.ac.uk

FN1. Selvakumar a/l Murugiah v Thiagarajah a/l Retnasamy [1995] 1 M.L.J. 817.

FN2. Clydebank Engineering and Shipbuilding Co Ltd v Don Jose Yzquierdo &

Castaneda [1905] A.C. 6.

FN3. Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co Ltd v New Garage & Motor Co [1915] A.C. 79.

FN4. Public Works Commissioner v Hill s [1906] A.C. 368.

FN5. Clydebank Engineering [1905] A.C. 6.

2009 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

CONSTLJ 2009, 25(2), 103-116

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY

Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116

(Cite as: Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116)

Page 15

FN6. Maniam v The State of Perak [1975] M.L.J. 75.

FN7. Linggi Plantations Ltd v Jagatheesan [1972] 1 M.L.J. 89.

FN8. Larut Matang Supermarket Sdn Bhd v Liew Fook Yung [1995] 1 M.L.J. 379.

FN9. Selvakumar a/l Murugiah v Thiagarajah a/l Retnasamy [1995] 1 M.L.J. 817.

FN10. N.M. Robinson, Construction Law in Singapore and Malaysia, 2nd edn (Asia,

Singapore: Butterworths, 1996).

FN11. V. Powell-Smith, "The Malaysian Standard Form of Building Contract

69)" [1990] Malayan Law Journal.

(PAM/ISM

FN12. Selvakumar a/l Murugiah v Thiagarajah a/l Retnasamy [1995] 1 M.L.J. 817.

FN13. Selvakumar a/l Murugiah v Thiagarajah a/l Retnasamy [1995] 1 M.L.J. 817.

FN14. Chaplin v Hicks [1911] 2 K.B. 786.

FN15. L.C. Fong, The Malaysian PWD Form of Construction Contract (Asia: Sweet &

Maxwell, 2004).

FN16. Allson International Management Ltd v LA Cemara Resort Management Sdn Bhd

[2001] M.L.J.U 634 (unreported).

FN17. Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Co Ltd v New Garage & Motor Co [1915] A.C. 79.

FN18. BFI Group of Companies Ltd v DCB Integration System Ltd [1987] C.I.L.L. 348.

FN19. Selvakumar a/l Murugiah v Thiagarajah a/l Retnasamy [1995] 1 M.L.J. 817.

FN20. Lion Engineering Sdn Bhd v Pauchuan Development Sdn Bhd [1997] 4 A.M.R.

3315.

FN21. Sakinas Sdn Bhd v Siew Yik Hau [2002] 5 M.L.J. 497.

FN22. Joo Leong Timber Merchant v Dr Jaswant Singh a/l Jagat Singh [2003] 5 M.L.J.

116.

FN23. Hadley v Baxendale (1854) 9 Ex. 341.

FN24. Temloc Ltd v Errill Properties Ltd (1987) 39 B.L.R. 30.

FN25. Hadley v Baxendale (1854) 9 Ex. 341.

FN26. Hadley v Baxendale (1854) 9 Ex. 341.

FN27. Lion Engineering Sdn Bhd v Pauchuan Development Sdn Bhd [1997] 4 A.M.R.

3315.

2009 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

CONSTLJ 2009, 25(2), 103-116

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY

Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116

(Cite as: Const. L.J. 2009, 25(2), 103-116)

Page 16

FN28. Selvakumar a/l Murugiah v Thiagarajah a/l Retnasamy [1995] 1 M.L.J. 817.

FN29. R.M. Clark, "Make Liquidated Damages Work" (2003) http://

www.aaceipr.org/articles.php [Accessed 9 May, 2006].

FN30. C.L. William, "Calculating Delay Claims: An Overview of the Components"

(1997), available at http://library.findlaw.com/2000/May/1/128083.html [Accessed

January 15, 2009].

FN31. S. Dave, "Liquidated Damages" (2006), available at http://

blawg.midwestconstructionlaw.com/damages_claims/index.html [Accessed January 15,

2009].

END OF DOCUMENT

2009 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Orig. US Gov. Works.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- JCT Construction Management GuidenceDocumento50 pagineJCT Construction Management Guidenceagonzalezcordova100% (4)

- Evaluating Contract Claims PDFDocumento2 pagineEvaluating Contract Claims PDFJustin0% (3)

- CCDC Documents DescriptionsDocumento6 pagineCCDC Documents Descriptionsmynalawal100% (1)

- The Law of Construction Contracts in the Sultanate of Oman and the MENA RegionDa EverandThe Law of Construction Contracts in the Sultanate of Oman and the MENA RegionNessuna valutazione finora

- Pam ContractDocumento21 paginePam Contractteeyuan100% (6)

- Time-Bar Clauses in Construction ContractsDocumento12 pagineTime-Bar Clauses in Construction Contractsyadavniranjan100% (1)

- Contracts, Biddings and Tender:Rule of ThumbDa EverandContracts, Biddings and Tender:Rule of ThumbValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- Building Contract 2019Documento12 pagineBuilding Contract 2019Nurul KhazieeqahNessuna valutazione finora

- Issues On Sub-Contract's Direct Payment - 221219 - 123348Documento7 pagineIssues On Sub-Contract's Direct Payment - 221219 - 123348Nazreen Farina Ahmad SabriNessuna valutazione finora

- Retention MoneyDocumento4 pagineRetention Moneyola789Nessuna valutazione finora

- Contractors Right of Action For Late or Non Payment by The EmployerADocumento31 pagineContractors Right of Action For Late or Non Payment by The EmployerArokiahhassan100% (1)

- Doubts Raised On The Validity of Construction and Payment GuaranteesDocumento26 pagineDoubts Raised On The Validity of Construction and Payment Guaranteesanon_b186Nessuna valutazione finora

- Topic 01 Suspension and Termination 2014Documento15 pagineTopic 01 Suspension and Termination 2014Kaps RamburnNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is The Recent Position On Retention Sums in Malaysia?: RticleDocumento3 pagineWhat Is The Recent Position On Retention Sums in Malaysia?: RticleJordan TeeNessuna valutazione finora

- Amending Standard Form ContractsDocumento10 pagineAmending Standard Form ContractsHoang Vien DuNessuna valutazione finora

- Disruption Claims in Construction ContractsDocumento29 pagineDisruption Claims in Construction ContractsDimSol100% (2)

- The Cost of Delay and Disruption 2Documento12 pagineThe Cost of Delay and Disruption 2Khaled AbdelbakiNessuna valutazione finora

- Delay and Disruption Claims March 2014 PDFDocumento31 pagineDelay and Disruption Claims March 2014 PDFNuruddin CuevaNessuna valutazione finora

- Comparison of Time Adjustment ClausesDocumento19 pagineComparison of Time Adjustment ClausesDaniel WismanNessuna valutazione finora

- The Cost of Delay and DisruptionDocumento11 pagineThe Cost of Delay and DisruptionAmir Shaik100% (1)

- LD & GD - Apr 2022Documento20 pagineLD & GD - Apr 2022Anonymous pGodzH4xLNessuna valutazione finora

- Construction Disputes in OmanDocumento2 pagineConstruction Disputes in OmanSamia MansourNessuna valutazione finora

- Differences in JC T ConditionsDocumento4 pagineDifferences in JC T ConditionsShawkat AbbasNessuna valutazione finora

- Negotiation of Construction ClaimsDocumento27 pagineNegotiation of Construction ClaimsGiora Rozmarin100% (3)

- Assignment SupportDocumento11 pagineAssignment SupportShashi PradeepNessuna valutazione finora

- Mitigating Contractor's Claim On Loss and Expense Due To The Extension of Time in Public Projects: An Exploratory SurveyDocumento12 pagineMitigating Contractor's Claim On Loss and Expense Due To The Extension of Time in Public Projects: An Exploratory SurveyWeei Zhee70Nessuna valutazione finora

- Construction Issues in OmanDocumento4 pagineConstruction Issues in Omanpoula mamdouhNessuna valutazione finora

- FIDIC & Recent Infrastructure Developments - BOTDocumento3 pagineFIDIC & Recent Infrastructure Developments - BOTIvan FrancNessuna valutazione finora

- Application of Loss of ProfitDocumento3 pagineApplication of Loss of ProfitBritton WhitakerNessuna valutazione finora

- Contractual Limitations and Change Management of EPC ContractsDocumento18 pagineContractual Limitations and Change Management of EPC ContractsZhijing Eu100% (2)

- Cipaa Utm PDFDocumento18 pagineCipaa Utm PDFAbd Aziz MohamedNessuna valutazione finora

- Assignment 1 - Project Communication SkillsDocumento8 pagineAssignment 1 - Project Communication SkillsrajnishatpecNessuna valutazione finora

- Contractors - Claims For Loss and Expense Under The Principle - TraDocumento42 pagineContractors - Claims For Loss and Expense Under The Principle - Trasoumen100% (1)

- Splitting Contracts 101Documento5 pagineSplitting Contracts 101scrib07100% (1)

- Standard Construction ContractsDocumento17 pagineStandard Construction ContractsGnabBang75% (4)

- EotDocumento5 pagineEotrazeen19857218Nessuna valutazione finora

- Procurement Contract 2Documento13 pagineProcurement Contract 2Damilola AkinsanyaNessuna valutazione finora

- RIBA Loss and Expense GuideDocumento13 pagineRIBA Loss and Expense GuidekasunNessuna valutazione finora

- CDR509 Assignement-21001340-April.2023Documento12 pagineCDR509 Assignement-21001340-April.2023Mem Nabil RamadanNessuna valutazione finora

- EssayDocumento10 pagineEssayyusuf.zahr134Nessuna valutazione finora

- Concurrent DelaysDocumento10 pagineConcurrent DelaysDharmarajah Xavier IndrarajanNessuna valutazione finora

- Pay When PaidDocumento10 paginePay When PaidZinck HansenNessuna valutazione finora

- CONM40018 CWK Contract AdminDocumento8 pagineCONM40018 CWK Contract Adminirislin1986Nessuna valutazione finora

- Limitations of Liability in Construction ContractsDocumento3 pagineLimitations of Liability in Construction ContractsAhmed Mohamed BahgatNessuna valutazione finora

- Conditions Precedent To Recovery of Loss and ExpensesDocumento9 pagineConditions Precedent To Recovery of Loss and Expenseslengyianchua206Nessuna valutazione finora

- Construction Works - Defects LiabilityDocumento17 pagineConstruction Works - Defects LiabilityThabo SeaneNessuna valutazione finora

- Contract Administration For A Construction Project Under FIDIC Red Book ContracDocumento7 pagineContract Administration For A Construction Project Under FIDIC Red Book Contracthanlinh88100% (1)

- Contractor Claims For Prolongation Costs - A Comprehensive Guide - LexologyDocumento7 pagineContractor Claims For Prolongation Costs - A Comprehensive Guide - LexologyVishal ButalaNessuna valutazione finora

- 2011J KPK Practice Note Claims Key EssentialsDocumento4 pagine2011J KPK Practice Note Claims Key EssentialsPameswaraNessuna valutazione finora

- MBJ Vol 4 2010Documento9 pagineMBJ Vol 4 2010LokuliyanaNNessuna valutazione finora

- Submission Date: 15-06-2021: Course Code: AIS-407 Course Name: Financial Reporting & Professional IssuesDocumento20 pagineSubmission Date: 15-06-2021: Course Code: AIS-407 Course Name: Financial Reporting & Professional IssuesShibajit HalderNessuna valutazione finora

- Types of Contract 2013 Hand Outs PDFDocumento34 pagineTypes of Contract 2013 Hand Outs PDFNavajyoth ReddyNessuna valutazione finora

- A Comparison of NEC and JCTDocumento3 pagineA Comparison of NEC and JCTArul Sujin100% (2)

- Buildings: A Systematic Method To Analyze Force Majeure in Construction ClaimsDocumento22 pagineBuildings: A Systematic Method To Analyze Force Majeure in Construction ClaimsEmadNessuna valutazione finora

- Project Management For Procurement Management ModuleDa EverandProject Management For Procurement Management ModuleNessuna valutazione finora

- Irregularities, Frauds and the Necessity of Technical Auditing in Construction IndustryDa EverandIrregularities, Frauds and the Necessity of Technical Auditing in Construction IndustryNessuna valutazione finora

- Full Text ThesisDocumento397 pagineFull Text ThesisWen SiNessuna valutazione finora

- The Role of Online Store Atmospherics in Consumer BehaviorDocumento28 pagineThe Role of Online Store Atmospherics in Consumer BehaviorWen SiNessuna valutazione finora

- Sub-Contract and Assignment: Prepared By: Dr. SR Mohd Suhaimi Mohd DanuriDocumento34 pagineSub-Contract and Assignment: Prepared By: Dr. SR Mohd Suhaimi Mohd DanuriWen Si0% (1)

- Westlaw Document 05-35-01 LADDocumento16 pagineWestlaw Document 05-35-01 LADWen SiNessuna valutazione finora

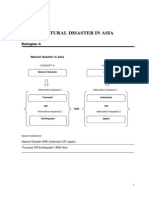

- Natural Disaster in Asia: Bahagian ADocumento1 paginaNatural Disaster in Asia: Bahagian AWen SiNessuna valutazione finora