Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Wilson (1994) Behavioral Treatment of Obesity. Thirty Years and Counting

Caricato da

Gustavo AyalaCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Wilson (1994) Behavioral Treatment of Obesity. Thirty Years and Counting

Caricato da

Gustavo AyalaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Adv. Behav. Res. Thu. Vol. 16, pp. 31-75, 1594.

Printed in Great Britain. All rights reserved.

BEHAVIORAL

THIRTY

0146.64W94 $24.00

@ 1993 Pergamon Press Ltd

TREATMENT

OF OBESITY:

YEARS AND COUNTING

G. Terence Wilson

Graduate School of Applied and Professional Psychology, Rutgers University, Busch

Campus, P.O. Box 819, Piscataway, NJ 08855, U.S.A.

Abstract - Beginning with the purely theoretical extrapolation of Skinnerian

principles to changing eating behavior in 1962, behavioral treatment has since

become the principal means of managing mild to moderate obesity. Over the years

treatments have become longer and more intensive, often being combined with

aggressive Very Low Calorie Diets. Weight loss has been correspondingly greater.

Yet a fundamental problem noted from the outset has remained: the inexorable

pattern of relapse irrespective of diverse attempts to improve long-term maintenance.

Although most patients maintain weight loss for at least a year, five year follow-ups

have shown that virtually everyone returns to their baseline weight. The health effects

of this pattern of loss and regain are unknown, but should not necessarily be judged

to be harmful. Reactions to the long-term ineffectiveness of weight control treatment

have varied. Whereas some critics have called for an end to treatment, proponents

have suggested that innovative maintenance strategies can be devised, and that

subtypes of obesity more amenable to behavioral treatment can be identified. It

is argued here that an understanding of the mechanisms that cause or at least

maintain obesity should determine treatment. This premise makes it unlikely that

behavioral treatments can be improved, but rather points to the direct modification

of the biological processes that regulate body weight. Cognitive-behavioral

treatment

is effective in reducing binge eating and other maladaptive behavior associated with

obesity. It can potentially improve nutrition and increase physical activity, resulting

in significant health benefits if not weight loss.

INTRODUCTION

The first formal behavioral analysis of obesity and its treatment was

published 30 years ago (Ferster, Nurnberger, & Levitt, 1962). The title

of the journal in which this paper was published - Journal of Muthetic.sl

- has long since receded into the realm of being a favorite trivia question,

but not so the behavioral approach to the treatment of obesity which this

pioneering paper spawned. No one would have anticipated the remarkably

* From the Greek mathein meaning to learn (see Kazdin, 1978). The founder of

this journal defined mathetics as the systematic application of reinforcement theory to

the analysis and reconstruction of those complex behavior repertoires usually known as

subject-matter mastery, knowledge, and skill (Gilbert, 1962, p. 8). Publication of

the journal was discontinued after only two issues. One wonders how many behaviorists

- unfamiliar with such an arcane term and assuming a typological error - went searching

for the Journal of Mathematics. More than one review of the Ferster et al. (1962) paper

understandably referenced it in the Journal of Marhematics (e.g., Stunkard, 1976).

JABRT 16:1-C

31

32

G. T. Wilson

rapid professional embrace of behavioral treatment of obesity, even in

those heady and naively optimistic days of the beginning of behavior

therapy. It is now accepted as a matter of course that behavioral treatment

is a necessary component of any adequate obesity treatment program

(Wadden & VanItallie, 1992). Significantly, behavioral treatment has also

become a basic feature of commercial weight control programs such as

Weight Watchers (Stuart & Guire, 1978) and Optifast (Sandoz Nutrition

Co., 1987; Wadden, Foster, Letizia, & Stunkard, 1992).

The paper by Ferster and his colleagues (1962) which started all of this

was a speculative extension of the principles of operant conditioning to

modifying eating behavior, or what the authors in their behavioristic zeal

repeatedly referred to as the act of putting food into ones mouth.

The well-known principles of stimulus control, chaining, shaping, and

reinforcement were brought to bear on developing self-control*

over

what the authors saw as the self-evident problem in obesity, namely eating

too much. As they put it, the act of putting food into ones mouth is

reinforced and strongly maintained by its immediate consequences: the

local effects in the gastro-intestinal system. But excessive eating results

in increased body-fat and this is aversive to the individual (p. 87). The

strategy, therefore, was to manipulate reinforcement contingencies so that

the ultimate aversive consequences of becoming fat came to control

current eating behavior and hence limit the amount of weight that was

gained. For example, Ferster et al. (1962) proposed that patients recite

the adverse effects of being fat and look at unattractive pictures of

themselves in a bathing suit. Among the other learning-based strategies

these psychologists recommended were: gradual weight loss to ensure

that deprivation

did not undermine self-control (food restriction); a

balanced diet to avoid increasing the reinforcing value of a particular

foodstuff; discriminative control, namely, narrowing the conditions under

which food was eaten; and seeking alternative, prepotent reinforcers with

which to supplant eating.

It is noteworthy that Ferster et al. (1962) reported no data in what was

to be so influential a paper. However, citing personal communication from

Ferster, a subsequent publication by Penick, Filion, Fox, and Stunkard

(1971) reported that the results of the Ferster et al. (1962) approach were

disappointing.

The modal weight loss of the 10 patients in (Fersters)

program was only 10 pounds, with a range from 5 to 20 (p. 49).

The early application of behavioral (reinforcement) principles to the

treatment of obesity also took place via a different route. Impressed by

2 Although the authors used the term self-control, they were describing situational

control by the arrangement of relevant environmental contingencies.

Behavioral Treatment of Obesity

33

the success of operant conditioning principles in the treatment of anorexia

nervosa, (Blinder, Freeman, & Stunkard, 1970), Stunkard experimented

with the use of reinforcement principles with a small number of carefully

selected obese patients (see Stunkard, 1976). This was a significant

development because Stunkard was a leading authority on obesity, and

the author of what were already on their way to becoming the two classic

summary verdicts on the relative ineffectiveness of the treatment of obesity.

The first was that Most obese persons will not stay in treatment for obesity.

Of those who stay in treatment most will not lose weight and of those who

do lose weight, most will regain it (Stunkard, 1958, p. 79). The second

was that regardless of what treatment was used, only 25% of obese patients

lose as much as 20 pounds, and only 5% as much as forty pounds (Stunkard

& McLaren-Hume,

1959). Stunkard summarized his initial experience with

the behavioral treatment of obesity as follows: After an initial weight loss

of 10 or 15 pounds, the patient had stopped losing weight . . . the program

did seem to have some influence, but it was disappointingly weak and

short-lived (reported in Stunkard, 1976, p. 216). This outcome did not

improve on his earlier gloomy evaluation of treatment effectiveness. He

decided to abandon behavior therapy for obesity. Then, in 1967, there

occurred the event which not only reversed Stunkards decision at the

time, but also fundamentally changed the way obesity would be treated

in the future.

Drawing upon Ferster et al.3 (1962) behavioral analysis of obesity, Stuart

(1967) implemented a multicomponent behavioral treatment program with

10 patients. Two of the 10 patients were excluded, one because she became

pregnant, the other (a probable psychotic) because she wanted some

other form of therapy. Of the remaining eight patients, all lost more

than 20 pounds, and half lost more than 40 pounds, following a mean

of only 26 half-hour treatment sessions over a one year period. Strikingly,

all showed a continuing trend for weight loss over the course of the

entire year. Stunkard (1976) described his excitement on learning of

these results as follows: I could hardly believe my eyes when I read

it. For in this report on Behavioral Control of Overeating,3 Richard

Stuart . . . reported the best results that had ever been obtained in the

outpatient treatment of obesity (Stunkard, 1976, p. 217). The impact

on the field was dramatic. Clinical practice was transformed. Based on

on this report and a subsequent elaboration of the treatment program

(Stuart, 1971), and a best-selling book describing the program (Stuart &

Davis, 1972), this behavioral approach was virtually institutionalized as the

3 Note in the title the then standard assumption that overeating

treatment of obesity.

is the target in the

34

G. T. Wilson

treatment for obesity. Clinical research was galvanized, and there followed

a remarkable increase in research activity on the treatment of obesity.

BEHAVIORAL

Assumptions

TREATMENT

IN THE 1970s

About the Nature of Obesity

Nowhere in the Ferster et al. (1962) analysis of obesity was there any

mention of genetic predisposition to obesity, individual differences, or the

biology of fat metabolism and weight regulation. Consistent with their

philosophy of radical behaviorism, the authors concentrated simply on

eating behavior - the act of putting food into ones mouth. This analysis

must be put in historical context. Those were the days of the beginning of

behavioral treatment, when the young Turks surged into the analysis and

modification of a wide range of clinical problems armed with the apparent

power and precision of learning principles and procedures.

In a revealing observation, Stunkard (1976) noted that at the time of

his landmark 1967 publication, Stuart had chosen obesity as a subject

of study for two simple reasons: it provided a convenient and objective

measure of the effectiveness of the treatment (i.e., pounds lost); and

a detailed description of a behavioral program for obesity was already

available (p. 217). The basic assumption behind behavioral treatment

was that obesity was due to excess food intake, which was the product

of maladaptive eating habits. Logically, therefore, treatment focused on

directly modifying eating behavior. The relevance of exercise began to

be noted in the 197Os, and increasing the behavior of physical activity

became a complementary treatment target (Mahoney & Mahoney, 1976;

Stuart & Davis, 1972). The biological basis of obesity was ignored or at

least de-emphasized, as it was in other clinical disorders targeted by the

early applications of behavior modification.

Somewhat lost in all the optimistic focus on modifying eating behavior

was the expression of a broader and more cautionary view. For example, in

an early warning, Stunkard and Mahoney (1976) concluded that given the

complex nature of the various factors involved in regulating body weight, a

behavior modification program which is successful in reducing body weight

and body fat may not be simply a matter of unlearning maladaptive eating

habits and learning more appropriate ones. Such a program may instead

have helped a person who biologically should be obese to maintain a

statistically normal, but biologically abnormally low, body weight (p. 54).

Stunkard and Mahoneys warning accurately predicted what was later to

become an overriding issue in the field.

The decade ended with a prescient critique of behavioral treatments

of obesity by Wooley, Wooley, and Dyrenforth (1979) in the Journal

Behavioral Treatment of Obesity

35

of Applied Behavior Analysis, the bastion of applied behaviorism. They

argued that the application of behavioral techniques would result in

failure - failure having less to do with the ingenuity and technical

adequacy of techniques than with limitations in the explanatory power

of the (behavioral) model itself (p. 4). Wooley et al. (1979) underscored

two major problems with the behavioral model. The first was that neither

maladaptive eating behavior nor the conditions responsible for faulty

learning of eating habits had ever been identified. The evidence even

suggested that obesity was not characterized by a distinctive eating pattern.

The second major problem was that, contrary to a core assumption of the

behavioral model, the evidence at the time indicated that obese people, in

general, did not eat more than their lean counterparts. (As discussed below,

subsequent studies employing improved methodology have disputed this

claim, at least for some obese patients.)

Beyond calling attention to the limitations of the behavioral model of

obesity, Wooley and her colleagues (1979) underscored the importance

of understanding the biology of weight regulation, and introduced into

the behavior modification literature a feminist perspective painting the

obese as misunderstood and maltreated victims of societal prejudice. They

ended their critical analysis by offering a different agenda for behavioral

researchers. Instead of applying themselves to conventional weight loss

programs, Wooley et al. called upon behavior therapists to

acquaint patients with the facts about obesity, including the lack of evidence that

the obese eat more than others, the effects of dieting on metabolism, and the modest

outcomes of most treatment, and to engage them in a process of goal-setting based

on these facts. Although therapists tend to be reluctant to discourage patients, the

facts of their own experience will have discouraged them or given them hope. If the

experience of dieting has been one of constant failure, despite enormous effort, they

will be relieved to have their experience confirmed and understood, and some may

be better able to withstand the difficulties knowing that they are not exclusively

attributable to their own failings. Some may choose to give up dieting and work

on minimizing the negative consequences of being obese. Others will recognize

that weight loss is, in fact, relatively easy for them and worth the effort. It

has been our experience that few patients embrace these pieces of information

as rationalizations; the concept of rationalization, of course, implies a self-serving

denial of the truth, which in the case of obesity is not known. Put otherwise,

patients typically become interested in discovering what holds true for them. What

is their weight maintenance calorie level? How rapidly and for how long will they

lose at a given level? How unpleasant is it? What, exactly, are the benefits to be

expected from weight loss? (Wooley et al., 1979, p. 20).

Initial

Treatment Trials

Behavioral researchers attacked the problem of obesity as they had

other clinical disorders, with an emphasis on well-controlled studies of

short-term effects. One set of studies compared the effects of behavioral

treatments with those of comparison conditions designed to control for

36

G. T. Wilson

nonspecific therapeutic effects (e.g., Wollersheim, 1970) or alternative

interventions (e.g., Levitz & Stunkard, 1974). Behavioral methods proved

to be consistently superior to the methods with which they were compared.

Another set of studies adopted the dismantling strategy which had

been pioneered with such success in the development and evaluation

of systematic desensitization for phobic reactions (Lang, 1969). These

studies were designed to identify which of the many techniques used

in broad-spectrum treatment programs were responsible for weight loss

(e.g., Mahoney, 1974; Romanczyk, Tracey, Wilson, & Thorpe, 1973).

In an assessment of the state-of-the-art in the field, Jeffery, Wing, and

Stunkard (1978) concluded that research on the behavioral treatment of

obesity has achieved a popularity verging on faddism (p. 189).

Even at this early stage, however, caveats about the effectiveness of

behavioral interventions were beginning to be issued. In the introduction

of one of the first anthologies of behavioral treatments of obesity,

Foreyt and Frowirth (1977) cautioned that more recent findings . . . are

beginning to cast doubt on the efficacy of some of these newer techniques

in the maintenance of long-term weight loss (p. 1). Among others,

OLeary and Wilson (1975) noted that treatment studies produced only

modest weight losses. More substantial weight loss was precluded, they

argued, by the relatively brief duration of behavioral treatments. Since

the goal of these programs was gradual weight loss of no more than one

or two pounds a week, clinically significant weight loss would require

longer interventions. These authors also called for the development of

specific maintenance strategies which would promote continued weight

loss. Among the maintenance strategies which were suggested were:

booster sessions or continued, periodic contact with the treatment program

to sustain self-regulation of weight control; the active involvement of

significant others in providing social support; and individual tailoring

of treatment interventions to patients particular needs.

In still another state-of-the-art review of the behavioral treatment of

obesity, Wilson (1979) conceded that It may be that the effects of

biological factors in maintaining obesity cannot (or, possibly, should not)

be overcome through the use of behavioral methods aimed at altering

eating and exercise habits (p. 203). Nevertheless, he put forward the

alternative interpretation that the poor follow-up findings were due to

inadequate or incomplete applications of behavior therapy (p. 203). In

addition to the maintenance strategies noted above, Wilson (1979) joined

others in advocating the incorporation of the new cognitive principles

and procedures which were changing the nature of behavior therapy. In

particular, the implications of Banduras (1977) newly minted self-efficacy

theory, and Marlatt and Gordons (1979) relapse prevention model,

seemed to promise ever more powerful ways of promoting maintenance of

Behavioral Treatment of Obesity

37

behavior change. This analysis foreshadowed what was to become the main

response of behavioral researchers to persistent evidence of the long-term

ineffectiveness of treatment, namely, that the solution could be found in

the further elaboration and refinement of behavioral strategies (Brownell

& Jeffery, 1987; Perri, 1992; Wadden & Foster, 1992). These optimistic

prescriptions are predicated on the assumption that long-term maintenance

of weight loss is a realistic objective.

The exception to this fundamentally optimistic view of the modification

of obesity was Yatess (1975) blunt conclusion that the treatment of obesity

was an example of when behavior therapy fails. This antipodean verdict

was ignored. One of the rare responses to Yatess pronouncement deemed

it premature (Franks & Wilson, 1975). With the benefit of hindsight it

can be seen that Yates (1975) anticipated the current critical reaction to

the apparent ineffectiveness of behavioral treatment. Especially relevant

was his consideration of different theories of obesity, particularly Nisbetts

(1972) then radical thesis that some individuals have no choice but to be

fat . . . and they are biologically programmed to be fat . . . (p. 433). As

Yates (1975) observed, If Nisbetts arguments are valid, then it may well

be futile, if not positively dangerous to attempt to induce weight reduction

in some obese persons (p. 148). (Stunkard and Mahoney (1976) were

to voice the same concern, as noted above.) Garner and Wooley (1991)

recently reached the same judgment, now much-publicized.

BEHAVIORAL

Assumptions

TREATMENT

IN THE 1980s

About the Nature of Obesity

This period marked the publication of several influential studies that

established the importance of genetic influences on obesity (Stunkard et

al., 1986, 1990) as well as the nature of some of the biological mechanisms

in the development and maintenance of obesity. Although the notion of a

set point around which body weight was biologically regulated remained

controversial, it became widely accepted that once obesity developed it

was defended by the body (Stallone & Stunkard, 1991). It became clear

that among the obstacles to permanent weight loss were the irreversible

increase in fat cell number caused by sufficient weight gain (Bjorntorp,

1986), increased metabolic efficiency following weight loss (Leibel &

Hirsch, 1984), and increased LPL activity following weight loss in obese

individuals (Kern et al., 1990).

Despite these findings on the genetic and biological bases of obesity,

behavioral treatment increasingly became the norm in attempts to modify

obesity. The point was made that genetic predisposition did not mean

that behavioral treatment would necessarily be ineffective. The rationale

38

G. T. Wilson

for behavioral treatment was pragmatic: the promotion of a negative

energy balance even though it was recognized that biological mechanisms

might make this unusually difficult for many obese individuals. There was,

however, little direct investigation of the specific mechanism(s) whereby

behavioral treatment produced a negative energy balance.

In their analysis of behavioral interventions, Craighead and Agras (1991)

pointed out that

treatment works primarily through enhancing restraint during the weight loss stage.

Although we cannot yet document them, there are quite likely many specific

ways through which that occurs. For subjects who were not initially practicing

high restraint, we hypothesize that the procedures teach them how to become

moderately high restrainers. Subjects learn to reduce intake by carefully structuring

eating behavior. The structured eating minimizes the occurrence of strong hunger

cues and provides cues to stop eating early, before the usual satiety cues. Subjects also

learn coping skills to handle eating that occursin responseto social,environmental,

and emotional cues, so fewer regulatory failures occur (Craighead & Agras, 1991,

p. 116).

The foregoing analysis summarized the thinking behind most comprehensive weight loss programs. However, Craighead and Agras (1991) went on

to state that Because most subjects do not continue to lose weight once

treatment is terminated, we hypothesize that the motivation to continue

the moderate levels of restraint suggested in behavioral programs comes

largely from social factors associated with being in treatment. It appears that

the benefits of weight loss are usually not intrinsically sujj5ciently reinforcing

to maintain restraint adequate to continue a negative energy balance (i.e.,

losing weight) (emphasis added) (p. 116). This conclusion not only

repudiates the rationale of Ferster et al.% (1962) original behavioral

analysis, it also attributes successful weight loss to ongoing contextual

influence of treatment. The implication is clear: continued weight loss or

even maintenance of treatment-induced weight loss depends on continual

treatment.

Despite the growing evidence on the biological regulation of weight,

most behavioral investigators still favored psychological explanations of

the failure to achieve lasting weight loss. In a well-known study, Craighead,

Stunkard, and OBrien (1981) compared behavioral with pharmacological

(fenfluramine) treatment. The result that attracted a great deal of attention

was the more rapid relapse of the combined behavioral and fenfluramine

treatment as opposed to the relative stability of the behavioral treatment

alone. The commonly proposed explanation was couched in terms of

attribution theory, i.e., patients in the combined treatment ostensibly

attributed their initial success to the drug, which when withdrawn, left

them without a sense of control or self-efficacy about regulating their weight

(Rodin, 1986; Wilson, 1986). Craighead et al. (1981) had not obtained

any data on their patients attributions, but this seemingly plausible

Behavioral Treatment of Obesity

39

explanation derived directly from laboratory research on attribution theory

and maintenance of behavior change (Davison & Valins, 1969). Weintraub

et al. (1992d) have subsequently shown that administering and then discontinuing DL-fenfluramine did not produce what they called negative

learning effects; these patients later did as well on a behavioral program

as patients who had received only placebo.

Stunkard (1989) offered a more compelling explanation. Drawing on

findings from animal research, he suggested that fenfluramine lowers the

level at which body weight is regulated. The effect is lost once the drug

is discontinued. Subsequent research on obese patients provides strong

support for the view that fenfluramine acts directly via specific biological

mechanisms to alter the level at which body weight is regulated (GuyGrand et al., 1992; Weintraub et al., 1992~). That fenfluramines actions

are biologically mediated does not negate the importance of a patients

attributions in weight loss programs. On the contrary, they need to be

addressed directly as indicated below.

Treatment Outcome Studies

Table 1. Summary Analysis of Selected Studies from 1974 to 1990 Providing Treatment

by Behavior Therapy and Conventional Reducing Diet

Number of studies

Sample size

Initial weight (kg)

Initial % overweight

Length of treatment (wk)

Weight loss (kg)

Loss per week (kg)

Attrition (%)

Length of follow-up (wk)

Loss at follow-up

1974

1978

1984

15

53.1

73.4

49.4

8.4

3.8

0.5

11.4

15.5

4.0

17

54.0

87.3

48.6

10.5

4.2

0.4

12.9

30.3

4.1

15

71.3

88.7

48.1

13.2

6.9

0.5

10.6

58.4

4.4

Source: Wadden, & Bartlett, (1992) (Copyright

sion.)

Guilford

1985-1987 19881990

13

71.6

87.2

56.2

15.6

8.4

0.5

13.8

48.3

5.3

5

21.2

91.9

59.8

21.3

8.5

0.4

21.8

53.0

5.6

Press. Reprinted with permis-

Table 1 summarizes the changing pattern of results in studies of the

behavioral treatment of obesity from 1974 to 1988-90 (Wadden & Bartlett,

1992). On average, weight loss in studies in the 1980s was almost double

that obtained in 1974. This improvement is attributable to the significantly

longer treatments. Not only had treatments become longer, they had

also become more intensive, multifaceted, and sophisticated. Behavioral

self-control methods aimed at altering eating habits and restricting caloric

intake were increasingly complemented by a focus on better nutrition, and

40

G. T. Wilson

strategies designed to increase physical exercise, improve interpersonal

relationships, and develop less dysfunctional attitudes about eating and

weight control (e.g., Brownell, 1989). The principles and procedures of

relapse prevention burst upon the scene of behavior change in the 1980s

(Marlatt & Gordon, 1985), and were quickly incorporated into behavioral

treatment programs for obesity (Brownell, 1992; Perri et al., 1988). In a

significant development, signalling the use of a more aggressive approach

to weight loss than the principle of gradualism that had characterized

earlier treatment, behavior modification was combined with Very Low

Calorie Diets (VLCDs) of 800 calories or less to produce substantially

greater amounts of weight loss (Craighead et al., 1981; Wadden & Bartlett,

1992; Wadden, Sternberg, Letizia, Stunkard, & Foster, 1989).

Despite these advances, two major problems remained. The first was that

although longer treatments produced greater weight loss, the effect was

limited. Per-r-i, Nezu, Patti, and McCann (1989) extended their treatment

program to 40 weeks. Subjects lost 9.9 kg during the first 20 weeks, but

only an extra 3.6 kg from week 21 to 40 even though they remained clearly

obese. The second problem was the continuing failure to achieve long-term

maintenance of weight loss regardless of length or breadth of the initial

treatment.

The long-term ineffectiveness of behavioral treatments

Table 1 not only shows greater weight losses in more recent studies,

but also longer follow-ups. Weight loss produced by combined behavioral

and VLCD treatment was maintained reasonably well at one year followup; roughly two-thirds of weight loss is kept off (Wadden, Stunkard, &

Liebschutz, 1988). Combined behavioral and VLCD treatment resulted in

significantly better maintenance than VLCD treatment alone (Wadden &

Bartlett, 1992). In possibly the most impressive demonstration of long-term

weight loss, Ohno and his colleagues (1991) in Japan showed that the

majority of their obese patients maintained their weight loss at two and

even three year follow-ups. Nevertheless, although progress was made

during the 198Os, with longer and more intensive treatment programs

producing greater weight loss and forestalling relapse for longer periods,

the fundamental problem remained. All follow-up studies showed the

same inexorable pattern, namely, gradual regain of weight over time.

The pace at which this weight regain occurs may vary across studies, but

the trend towards a return to baseline values is clear. This is even the case

in studies in which specific maintenance strategies have been implemented

during the follow-up period, as illustrated in the research of Perri and his

colleagues (1988). Even though the different maintenance strategies were

effective during the first six months following treatment, all conditions

Behavioral Treatment of Obesity

41

began to show unmistakable signs of consistent weight regain by the 12

month mark.

Given the trend towards weight regain in one and two year follow-ups,

it is not surprising that a five year follow-up showed that, on average,

virtually all patients had regained their weight, there being not even a

hint of the effectiveness of behavioral treatment (Wadden et al., 1989,

p. 45) (see Table 2). The investigators attributed the relapse to patients

failure to adhere to the behavioral strategies they had learned and that had

proved effective. It should also be noted that fully 55% of the patients in

this study sought other treatment for weight control treatment during the

five year follow-up period. (The corrected data in Table 2 are patients

self-reported weights at the time they received additional treatment.)

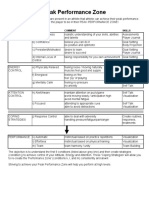

Table 2. Mean Weight Changes in Kilograms (from Baseline) at Post-treatment and One

and Five Year Follow-ups

Follow-Up

Condition

End of

Therapy

1 Year

5 Year

(uncorrected)

5 Year

(corrected)

Diet alone

Behavior therapy

Combined therapy

23

22

31

-13.1 k1.0

-13.0 f1.4

-16.8 f1.2

-4.7 51.5

-6.6 k1.9

-10.6 f1.6

-5.1 22.6

+2.9 f1.7

+0.8 k2.4

+l.O f1.6

-12.7 +I.8

+2.9 f2.4

Source: Wadden et al. (1989). Copyright Buildford

Press. Reprinted with permission.

This additional treatment did little to alter the final results. The longterm failure of this comprehensive, state-of-the-art program combining

behavioral treatment with a VLCD, implemented by highly respected

experts in the treatment of obese patients, is discouraging. The data,

however, are consistent with previous five year evaluations of the outcome

of behavioral interventions (Stalonas, Perri, & Kerzner, 1984; Stunkard

& Penick, 1979). These findings from Wadden and his colleagues (1992)

reaffirm once more the validity of Stunkards (1958) edict that among

those patients who lose weight, most will regain it.

BEHAVIORAL

TREATMENT

IN THE 1990s

Behavioral and dietary treatment of obesity is at the crossroads. Increasingly it is the focus of critical attention, as exemplified in the recent

NIH Technology Assessment Conference (NIH, 1992). Reactions to

the evidence showing the disappointing long-term outcome of behavioral

treatment, and to the criticism this has engendered, have taken very

different forms.

42

G. T. Wilson

Do Existing Data Underestimate the Effectiveness of Behavioral

Treatment?

Measuring the effectiveness of treatment

The long-term effectiveness of treatment of obesity is typically framed in

terms of the extent to whichpatientsarebelow the pretreatmentor baseline

level. As Brownell and Jeffery (1987) have pointed out, this assumes that

these individuals would have maintained a stable weight in the absence of

any treatment. Yet there is evidence that people gain weight over time,

and that this tendency is marked in the obese (Shah, Hannan, & Jeffery,

1991). Accordingly, Brownell and Jeffery (1987) suggested that long-term

effects of treatment must be interpreted with a probable weight gain as

the comparative yardstick.

Garner and Wooley (1991) have challenged this suggestion. They charge

that alternative outcomes, such as obese individuals maintaining a stable

weight or even losing weight had they not received treatment, are as

plausible as weight gain over time. Although Gamer and Wooley are

technically correct in noting that different reference points are possible for

evaluating long-term effects of treatment of obesity, the available evidence

would appear to lend credence to Brownell and Jefferys (1987) suggestion.

Nonetheless, even if it is conceded that the results of behavioral treatment

should be compared against a presumed increase in baseline weight over

time, the five year outcome data would arguably still be modest at best.

Formal treatment versus self-initiated change

Another interpretation of dismal long-term effects of dietary and behavioral treatment of obesity is that they are based on a biased sample

of obese people. According to this view, patients who seek treatment

in controlled clinical trials are those who have the most difficulty losing

weight (Brownell, 1992). For example, binge eaters are over-represented in

obese patients seeking clinical treatment. It is estimated that 30% or more

of obese patients report regular binge eating, compared with only 2% in

the general population (Bruce & Agras, 1992; Spitzer et al., 1992).

Studies have consistently shown significantly greater levels of psychopathology in obese binge-eaters compared with obese non-bingers. Marcus

et al. (1990) found that 60% of obese binge eaters had a history of at least

one psychiatric disorder, as opposed to 28% of non-bingers. Schwalberg,

Barlow, Alger, and Howard (1992) found a 60% lifetime prevalence of

affective disorder and a 70% lifetime rate of anxiety disorders in their

sample of obese binge eaters (see also Hudson et al., 1988; Yanovski,

1993). The presence of this comorbid psychopathology is very likely to

complicate treatment of obesity. It has commonly been assumed that binge

Behavioral

Treatment

of Obesity

43

eating in obese patients is associated with greater attrition from treatment

and poorer weight loss (Keefe et al., 1984; Spitzer et al., 1993; Wilson,

1976). Recent data indicate otherwise, however. For example, a study by

Wadden et al. (in press) found that behavioral treatment combined with a

VLCD showed no differences between obese binge eaters and non-bingers

in drop-out rate or post-treatment weight loss. Other studies have similarly

failed to show that binge eating is a negative prognostic factor (Brody,

Walsh, & Devlin, 1993; Marcus et al., 1990; Telch & Agras, 1993; Yanovski

& Sebring, in press).

Whether on account of the presence of binge eating or other complications, it would be well to avoid Berksons bias (Helzer & Pryzbeck,

1988) and not generalize from the results of randomized clinical trials to

all obese individuals. Brownell (1992) underscores this point in raising the

possibility that the results from informal, self-initiated attempts to lose

weight might be superior to those from formal clinical trials which are

cited to document the long-term ineffectiveness of dietary and behavioral

treatment. Brownell (1992) buttresses this argument with reference to

Schachters (1982) much-cited but largely anecdotal observations about

people who quit smoking and lost weight by themselves without any

involvement in formal treatment. According to Schachter (1982), the

success rates of these self-quitters were substantially better than those

in the clinical literature. Rzewnicki and Forgays (1987) published a similar

report.

In contrast to Schachters (1982) conclusion, a searching and systematic

analysis of the scientific literature by Cohen et al. (1989) showed that

cessation rates were no better for unselected individuals who tried to

quit smoking cigarettes on their own, than for those obtained in formal

treatment trials. If this is true for cigarette smoking, there is little reason

to believe that self-initiated attempts at weight control would prove more

successful than professional treatment. If anything, it could be argued that

obesity is a more intractable problem than cigarette smoking on both

theoretical and empirical grounds, as argued below.

There are still other reasons to question whether unselected obese

individuals in the general population do better in maintaining weight loss

than the patients represented in published clinical trials. Several studies

have investigated the effects of behavioral interventions in community

settings and worksite programs. It can be argued that the participants

in these studies are similar to the general population. Yet the results

of these studies have been as disappointing as those from clinic-based

studies (Jeffery, 1992; Stunkard, Cohen, & Felix, 1989). People who attend

commercial weight loss programs might have a less severe weight problem

with fewer complications than those who enter university-based treatment

programs. Stunkard (1989) made this assumption in recommending that

44

G. T. Wilson

commercial programs may be the intervention of choice for people with

only mild obesity. Unfortunately,

there are no data to substantiate this

reasonable recommendation.

Skeptics will be quick to suggest that the

failure of these programs to publish any systematic evaluation of long-term

weight loss in these programs is not a coincidence. Research that would

provide this information is a priority.

In sum, it certainly is plausible to assume that the patients in predominantly university-based treatment programs that have yielded such

disappointing long-term results are not representative of the full spectrum

of obese people trying to control their weight. It may be that unselected

obese individuals in the population are more successful in their weight

control efforts. Nevertheless, the reality of the long-term ineffectiveness

of behavioral treatment for those patients who seek formal treatment

programs remains a problem, and it is this population that is the focus

of the present paper.

Can Specific Treatments Be Matched to Particular Subgroups of Patients?

It is now widely acknowledged that most clinical disorders are heterogeneous in nature, with no single treatment appropriate for all patients.

This is likely to be true of obesity, and it has been proposed that the

better treatment outcome will result from matching specific treatments

to particular subgroups of homogeneous patients (Brownell & Wadden,

1992). Treatments might be matched to subgroups of patients identified

either according to biological or behavioral characteristics. As an example

of the former, Stallone and Stunkard (1991) speculate that behavioral

treatment might be appropriate for patients whose metabolic rate does

not decline in response to weight loss (non-regulated

obesity) but

inappropriate for those in whom this occurs (regulated obesity).

A problem with matching treatments to subgroups, however, is that

reliable predictors of treatment outcome have yet to be established

(Wadden & Letizia, 1992). The identification of treatment-specific predictors of outcome is even more elusive. The rationale for the search

for predictors of outcome is predicated on the assumption that there is

considerable variation in response to weight loss treatments (Brownell &

Wadden, 1992). This conclusion, however, is accurate only with respect

to short-term outcome. All of the available evidence indicates that there

seems to be remarkably little variation in outcome in long-term treatment

follow-ups. Most patients return to their baseline weights (Wadden et

al., 1989).

Whether or not matching individual patient characteristics to particular

treatments will improve long-term weight loss remains to be seen. It

warrants continued research attention. In the meantime the identification

Behavioral Treatment of Obesity

45

of subgroups of obese patient with different needs can be useful in other

ways, as Brownell and Wadden (1992) have indicated. Consider obese

binge eaters who, as discussed above, appear to be a distinctive subgroup

of patients. Initial studies indicate that both pharmacological (McCann &

Agras, 1990) and psychological (Smith, Marcus & Kaye, 1992; Telch et al.,

1990; Wilfley et al., 1993) therapies show promise in reducing binge eating

in obese patients. The available evidence shows that successful reduction

of binge eating in these patients does not result in significant weight loss.

Nevertheless, several benefits can be anticipated from the elimination of

binge eating in obese patients.

First, it might make it easier for them to participate and remain in more

conventional weight control treatments, the putative benefits of which are

discussed below. Second, it might prevent future weight gain. If binge

eating is a risk factor for obesity in some individuals, then successful

treatment of binge eating before the person becomes overweight might

prevent obesity (Agras et al., 1992). (The potential importance of early

intervention in the development of obesity is emphasized later in this

paper.) Third, it should increase patients sense of personal control,

which has a variety of positive psychological sequelae, including improved

adherence to behavior change strategies. Fourth, it should improve mood

and reduce associated psychopathology, important goals in their own

right.

Binge eating is a distinctive pattern of behavior (Fairburn & Wilson,

1993), whereas obesity is more akin to a chronic biological disorder. It is

not surprising, therefore, that behavioral treatment appears to be effective

in overcoming the former but not the latter. The current interest in binge

eating in a subgroup of obese patients should not prematurely narrow

the focus on differences in eating patterns among obese people. The

inclusion in DSM-IV of binge eating disorder (BED) as an example of

EDNOS could well have this undesirable effect (Fairburn, Welch, & Hay,

1993). Rather, the study of eating behavior of obese individuals should

be broadened to include all forms of dietary restriction and overeating.

Wadden et al. (in press) provide an illustration of the importance of taking

an inclusive view of different patterns of overeating. These investigators

failed to confirm previous reports that binge eating is associated with

greater drop-out rates and less weight loss in obese patients. Overeating

in the absence of loss of control, however, was associated with a poorer

response to behavioral treatment.

Another example of the value of a broad behavioral analysis of eating

behavior in obese patients is provided by Schlundt et al. (1991). A

hierarchical cluster analysis of two weeks of detailed self-monitoring

of eating habits produced the following five different eating patterns:

moderately healthy eating habits; chronic food restriction; alternating

46

G. T. Wilson

patterns of restriction and binge eating; emotional overeating; and unrestricted overeating. Significantly, the chronically restricting cluster had less

lean body mass, lower resting metabolic rate, and higher waist-to-hip

ratios than the unrestricted overeaters. Over the course of behavioral

treatment the different groups did not differ in drop-out rates, amount

of weight loss, or exercise compliance. Consistent with other research,

the alternating dieting-binge eating cluster reported greater emotional

maladjustment than the other four clusters.

There is good reason to continue the behavioral analysis of eating

behavior of obese individuals. Following a series of studies in the 197Os, it

was commonly assumed that obese individuals ate no more than their lean

counterparts (Wooley et al., 1979). The so-called myth of overeating

was attributed to selective attention by biased observers whose availability

heuristic primed them to see fat people eat a large amount of food

(Garner & Wooley, 1991). If obese patients do not overeat relative to nonobese people, it would undermine the rationale of behavioral treatment

aimed at reducing energy intake. That many obese individuals who have

lost weight show reduced energy requirements and do not overeat has

been shown (Leibel & Hirsch, 1984). Nonetheless, recent research using

doubly labeled water to objectively measure total energy expenditure has

shown that some obese patients eat significantly more and exercise less

than they report (Lichtman et al., 1992). The subjects in this important

study attributed their inability to lose weight to genetic and metabolic

factors rather than their eating behavior. This discrepancy between actual

and perceived energy intake and expenditure has obvious implications

for treatment. The reasons for the discrepancy remain to be explored,

although there is reason to discount deliberate falsification (Danforth

& Sims, 1992). It does, however, focus attention on patterns of eating

and exercise, and underscores the potential value of behavioral analysis

of consumption.

Should Treatment Goals be Reassessed?

Brownell and Wadden (1992) have proposed that we abandon traditional

weight loss goals based on weight tables in favor of what they describe as

reasonable weight. The notion of determining a reasonable weight for

individual patients is not without problems, and Brownell and Wadden

(1992) provide only general guidelines that will leave most practitioners

in doubt. Nevertheless, this proposal recognizes that significant health

benefits are associated with relatively modest weight losses that fall far

short of the healthy ideal and patients own aesthetic ideals. The rationale

is that these goals are unrealistic and hence will only discourage efforts at

lasting weight loss. The hope is that a more modest goal will result in

Behavioral Treatment of Obesity

47

improved maintenance. (In his discussion of the limitations of his landmark,

3 l/2 year long study of drug and behavioral treatment which is discussed

below, Weintraub (1992, p. 644) speculated that a less demanding and

individually-tailored

goal weight might have improved outcome for some

of the patients.)

Emphasizing the primary importance of the health benefits of weight

loss in the obese, Blackburn and Rosofsky (1992) have similarly proposed

a 10% solution for weight goals, namely, losing just 10% of body weight.

This relatively modest amount of weight loss can be shown to have positive

effects on health.

Brownell and Waddens (1992) proposal is both sensible and humane.

Nevertheless, whether the adoption of the more modest and flexible

concept of a reasonable weight will lead to improved maintenance is

debatable. The available data give no particular reason to expect patients

to maintain a weight loss of 10 lbs as opposed to 30 lbs.

Can Behavioral

Treatment Be Improved?

Another response is to emphasize the improvement in clinical outcome

from the 1970s to the 1980s as summarized in Table 1, and to argue that

continued technical advances in intervention programs will produce still

greater improvements (Brownell, 1992; Kirschenbaum et al., 1992; Perri,

1992; Wolfe & Marlatt, 1992). As described earlier above, this faith in our

ability to develop still more powerful forms of behavioral treatment has

been a consistent theme in the behavior therapy literature on obesity. In

support of this view is the evidence of successive refinement of cognitivebehavioral treatments for other clinical disorders with increasingly favorable clinical outcomes (Barlow, 1993). Nor can it be denied that as they

have become more comprehensive and longer in duration, behavioral

treatments for obesity have produced better results. Nonetheless, the

long-term outcome has not changed, and the possibility that this is no

longer a realistic expectation in the treatment of obesity must be given

serious consideration.

If behavioral treatment for obesity is to become more effective, what

are the new concepts from psychological science which will inform this

therapeutic retooling? The modern advocates of improving the effectiveness of behavioral treatment identify little, if anything, which is conceptually new (Brownell & Wadden, 1992; Gremouw & Darner, 1992;

Perri, 1992; Wolfe & Marlatt, 1992). For example, consistent appeal

is made to the presumed utility of the philosophy and procedures of

relapse prevention. Yet relapse prevention, the creative formulation of

Marlatt and Gordon (1979) within the field of alcohol abuse, was quickly

introduced into the behavioral literature on obesity (Wilson, 1979), and

JAW 16:1-O

48

G. T. Wilson

has been a feature of many behavioral treatment programs over the past

decade (Brownell, 1989; Brownell, Marlatt, Lichtenstein, & Wilson, 1986;

Sternberg, 1985).

In a recent elaboration of relapse prevention philosophy applied to the

treatment of obesity, Wolfe and Marlatt (1992) reject the dichotomous

framework in which one is either on or off a diet, in favor of a broader

focus on healthy lifestyle changes. A rejection of traditional diet thinking

was an integral feature of the original Stuart and Davis (1972) prototype of

behavioral treatment. An explicit cognitive perspective on the maladaptive

nature of dichotomous thinking and related dysfunctional cognitions goes

back at least to Mahoney and Mahoneys (1976) analysis (cognitive

ecology: cleaning up what you say to yourself) in their straightforward

extension of cognitive restructuring to the treatment of obesity.

Arguing that the futility lies not in pursuing effective weight management approaches, but rather in evaluating them against inappropriate

standards (p. lSS>, Wolfe and Marlatt (1992) suggest reframing weight

management success. Instead of setting specific goal weights, the emphasis

shifts to approaching

their weight as a symptom of an undesirable lifestyle and focused on living a more

desirable life, knowing it would improve their bodies. They counted their successesin

small but exceedingly varied steps, such as learning the difference between complex

and simple carbohydrates, resisting an offered treat, losing a dress size, and gaining

the confidence to undertake new challenges. Each step enriched their lives and moved

them further from where they began. They were not on a diet, therefore, they never

had to begin maintenance or worry about relapsing. They actively chose to pursue

an improved quality of life. In the process, they lost the symptoms of the excessive

lifestyle they had left behind (Wolfe & Marlatt, 1992, p. 188).

Again, there is little here that will strike veterans in this field as new,

influenced as virtually all behavior therapists have been for some time

by Marlatt and Gordons (1985) pathbreaking analysis of the relapse

prevention model with its emphasis on lifestyle balance.

The contribution of relapse prevention training to the behavioral treatment of obesity has been systematically evaluated (Fremouw & Darner,

1992; Per-r-i, 1992). In one study, adding relapse prevention to a basic

behavioral treatment program was helpful only when combined with

continuing professional contact via telephone or mail (see Perri, 1992,

Table 19.1). In another, both relapse prevention and continuing post-treatment contact respectively facilitated maintenance of weight loss but did not

differ from one another (see Perri, 1992, Table 19.5). Most importantly,

the longest follow-up in these studies was only 18 months. Although the

data are admittedly still preliminary (Brownell, 1992; Fremouw & Darner,

1992) the relatively modest effects obtained with relapse prevention

training to date do not suggest that it will improve much upon the

disappointing outcome at five years.

Behavioral Treatment of Obesity

49

The limits of behavioral treatment

Behavioral treatment of obesity assumes that excess body weight is a

function, at least in part, of environmental influences (Ferster et al., 1962).

There is little question that this is the case. Although it is well-established

that body-mass index is strongly influenced by genetic factors (Sorensen,

Holst, Stunkard, & Skovgaard, 1992; Stunkard et al., 1990), this genetic

predisposition is expressed in interaction with specific environmental

conditions. A behavior genetic analysis by Grilo and Pogue-Geile (1991)

confirmed the importance of environmental

influences on weight and

obesity, although they accounted for less variance than genetic factors.

This analysis also demonstrated that it is non-shared environmental

influence that is important. Shared influence seemed irrelevant. Grilo

and Pogue-Geile comment that it is remarkable that individuals within

families who apparently share similar diets resemble each other so little

in weight (1991, p. 535).

Several other lines of evidence point to the importance of environmental

influences on obesity. The evidence for a trend of increasing weight gain

in the U.S.A. in recent decades is one (Gortmaker, Dietz, Sobol, &

Wehler, 1987; Jeffery, Folsom, Luepker, & Jacobs, 1984). Another is the

robust finding of an inverse correlation between socioeconomic status

(SES) and obesity (Sobal & Stunkard, 1989). This correlation can be

seen as showing that obesity leads to lower SES. It can also be argued,

however, that social class affects obesity. Women in higher social classes

seem more committed to societal ideals of thinness and have greater

resources to control their weight through dietary restriction and exercise.

There is evidence that eating disorders are more common among women

in higher social classes and that this is due in part to their higher rates of

dieting and pursuit of thinness (Hsu, 1990). Garn and Clark (1976) found

that adolescent females in higher income families started out fatter but

ended up leaner than those in lower income families.

The evidence for environmental influence on obesity seems clear. In

principle this environmental influence could be used to produce weight

loss or gain. Yet we have been unable to harness the power of these

environmental influences in formal treatment programs. Our environment

currently serves to encourage weight gain and undermine organized efforts

to lose weight. The hope that some new behavioral concept or procedure

will at last succeed in promoting long-term maintenance of weight loss

has worn thin. The prospect that no amount of fine-tuning of behavioral

principles will improve upon the current state of affairs must be faced.

Behavioral treatment, no matter how sophisticated, has had little long-term

success in lowering weight. With the wisdom of hindsight we should not be

surprised.

50

G. T. Wilson

Obesity is influenced strongly by genetic factors and once established, is

maintained by several potent biological mechanisms, including irreversible

fat cell formation (Bjorntorp,

1986) and increased metabolic efficiency

(Shah & Jeffery, 1991). Genetic influence is only predisposition and

not predestination, but it would be folly to ignore the power of this

predisposition as it plays out in an environment which exacerbates the

risk to the vulnerable person. Whether it is biological pressure that must

be resisted, or vulnerability that must be protected against, obese people

have to impose endless control (be it cognitive, behavioral, or more broadly

environmental)

on energy intake/expenditure.

Good, multicomponent

behavioral interventions provide training and support in shoring-up this

control. In principle it could be maintained for a lifetime, and a small

number of patients seem to be able to do just that, especially with

the help of social support and physical exercise. But these efforts are

up against an environment that (a) features abundant food, especially

fast food and other tempting sources of high calorie intake, and (b)

an increasingly sedentary lifestyle. We may have been asking too much

of obese people to exercise control continuously in the face of these

unremitting environmental influences. With respect to long-term weight

loss, the title of Stuart and Daviss (1972) influential book - Slim Chance

in a Fat World - was more telling than we appreciated at the time.

The plight of the obese person can be compared with that of someone

with psychoactive substance abuse disorder or an eating disorder. Alcoholics, for example, can stop drinking completely (and for the ones who

are physically dependent on alcohol this is the recommended course).

Despite environmental cues to drink, they can avoid the biggest threat

to self-control, namely, consumption of alcohol. The same applies to

cigarette smoking. In contrast, obese people have to eat each day of their

lives. They are necessarily in daily contact with internal and external cues

which regulate eating. Behaviorally speaking, the threat to control must

be greater under these conditions. It has been repeatedly documented

that obese patients on a VLCD not only lose a large amount of weight

quickly, but seem to do so with relative ease. Even obese binge eaters

cease to binge while on a VLCD (Telch & Agras, 1993). There is no

mystery here, no special property of the VLCD. As patients themselves

are quick to point out, a VLCD provides a structured form of energy

intake that artificially removes patients from the real world temptations

and frustration of coping with the demands of conventional eating. They

neither have to choose one food over another, nor expose themselves to

food-related cues in purchasing and preparing meals. It is the refeeding

period, the transition to normal eating with its inevitable demands on

self-control, that results in overeating and weight gain.

With problems such as alcohol abuse and eating disorders, putting aside

Behavioral Treatment of Obesity

51

the highly questionable disease theory view of addiction (Fingarette,

1987), the focus is on behavioral disorders. They are not chronic illnesses

of the sort obesity is now said to be. With alcohol abuse we can completely

eliminate maladaptive behavior (become totally abstinent) rather than seek

to regulate an underlying condition that will not change. Alcoholics may

have their own genetic/biological vulnerabilities,

but the evidence for

genetic predisposition is not as strong (many would argue it is quite weak,

e.g., McGue et al., 1992) as it is for obesity. In contrast to the biological

condition of obesity, the binge eating is a behavioral disorder that should,

in theory, be modifiable via behavioral treatment. The evidence indicates

that this is the case (Telch et al., 1990; Wilfley et al., 1993). As for

obesity, this analysis suggests that for the majority of patients, longterm weight reduction is feasible only to the extent that some form of

restructuring of their environment is made in which external controls are

imposed indefinitely. The closest approximation of such an intervention is

continual treatment. The available evidence indicates that the continued

contact of one form or another with a treatment program is the best

means of maintaining weight loss (Perri, 1992). But how feasible is such a

strategy? Would patients continue to attend formal maintenance sessions?

Clinical experience strongly suggests that attendance and adherence would

taper off.

Is Prevention More Important

Than Treatment?

The development of obesity is associated with biological changes, such

as an increase in number of fat ceHs, that make it difficult to lose weight

(DiGerolamo, 1991). The body comes to defend an obese state. It follows

from this that the focus should be on preventing excess weight gain in the

first place. For example, there is animal evidence showing that duration

and severity of weight gain influences the reversibility of dietary obesity

(Hill, Dorton, Sykes, & DiGirolamo,

1989). After 17 days of a high fat

diet, rats switched to ad lib feeding of low fat chow returned to control

levels of body weight and composition. After 30 days of the high fat diet,

however, rats did not return to control weight level, showing increased

energy expenditure and reduced energy requirements. The data underscore

previous findings that obesity is not simply maintained by overeating, and

that once established, dietary obesity is resistant to modification.

Dietz (1992) has pointed out that early onset obesity (in childhood and

adolescence) predicts more severe adult obesity and greater cardiovascular

morbidity in adult obesity. Moreover, the effect of adolescent obesity on

adult morbidity and mortality occurred independent of its impact on adult

weight status. These results point once more to the importance of early

prevention of weight gain.

52

G. T. Wilson

There is reason to believe that prevention might be more effective than

the treatment of established obesity. Epstein and his colleagues evaluated

the effects of two different forms of an eight month, family-based weight

loss program for obese children (ages 6-12 years) (Epstein, Valoski, Wing,

& McCurley, 1990). In the treatment that emphasized lifestyle change

and weight control in both the children and their parents, children lost a

significant amount of weight, most of which was maintained at a 10 year

follow-up. At that point, the children were maintaining a loss of seven

percent of their initial percent overweight. The treatment that focused

solely on changes in the childrens behavior resulted in relapse by the

five year follow-up. Parents in both treatments fared less well, returning

to their baseline weight at five years and showing increases in percent

overweight at the 10 year follow-up. Epstein (personal communication)

has reported that the long-term success of his family-based program has

been replicated in a subsequent study.

Given the well-documented failure to maintain weight loss in adults,

the long-term success of Epstein et al.% (1990) program may come as a

surprise. Uncovering the reasons for the discrepancy in outcomes would

seem to have significant theoretical as well as practical implications. One

prosaic hypothesis is that it is easier to establish healthy eating and activity

habits in children than adults. Another, drawing from the Hill et al. (1989)

data, is that early intervention is less likely to encounter the biological

obstacles posed by established obesity in adults.

It would be well to issue a caveat about interventions aimed at preventing

obesity in children. Care would have to be taken to ensure that they receive

adequate nutrition and do not develop the type of dietary restraint that

has been linked to the development of eating disorders and other forms of

psychological distress. More than anything else it would seem important to

encourage sensible eating habits, healthy nutritional choices, and increased

physical activity.

Prevention of excessive weight gain might also be attempted using a

different strategy. Binge eating appears to become more prevalent as

degree of overweight increases (Spitzer et al., 1992; Telch, Agras, &

Rossiter, 1988).4 Moreover, a large number of obese adults who binge

report that their binge eating preceded the development of obesity

(Wilson, Nonas, & Rosenblum, 1993). Accordingly, Agras et al. (1992)

have speculated that binge eating might be a risk factor for obesity in

some individuals. The elimination of binge eating in adults with established

obesity does not result in weight loss (Marcus, 1993). Agras et al. (1992),

4 A recent study by Wadden, Foster, Letizia, and Wilk (1992) failed to replicate these

findings, however.

BehavioralTreatment of Obesity

53

however, suggest that successful treatment of binge eating (for which

methods exist) in non-obese individuals might forestall the development

of obesity. If binge eating is viewed as a form of dietary-induced obesity,

the parallel to Hill et al.s (1989) data is obvious.

Do The Risks Outweigh the Benefits of Behavioral

Treatments?

Health risks

In their broadside against behavioral treatment of obesity, Gamer and

Wooley (1991) not only underscore its long-term ineffectiveness, but also

charge that it may often be harmful. The reason is that diet-induced

weight loss will be followed by weight regain, a pattern that has come

to be known as weight cycling (Brownell et al., 1986). Drawing largely

from animal studies, the generalizability of which to humans they admit is

unclear, Garner and Wooley (1991) caution that weight cycling can have

the following untoward effects: reduction in lean body mass relative to

body fat; enhanced metabolic efficiency, making future weight loss even

more difficult or even leading to still greater obesity; and increased risk

of cardiovascular disease. It may be weight cycling and not obesity per se,

they suggest, which is linked to morbidity and mortality in obese people.

The data on weight cycling are conflicting and controversial. Wing

(1992a) concluded that the bulk of the available evidence shows that weight

cycling has no effect on body composition, metabolic rate, or distribution

of body fat. In contrast, Rodin (1992) has shown that weight cycling is

associated with increased fat cellsize and LPL activity in abdominal fat.

According to Wing (1992a), the evidence on health outcomes in people,

despite inconsistencies, does suggest that weight variability has a negative

impact on all-cause mortality, and particularly cardiovascular mortality

(see also Lee & Paffenberger, 1992).5 Drawing causal inferences from

existing studies linking variability in weight to health outcomes is fraught

with difficulties, however.

One of the problems in interpreting these epidemiological findings is

determining whether the cycles of weight loss were voluntary or not.

The possibility that weight loss reflected an existing illness is difficult

to discount. Nevertheless, in their analysis of change in body weight

and longevity in Harvard alumni, Lee and Paffenberger (1992) carefully

excluded individuals with existing cardiovascular disease and cancer.

5 Note that these data come from epidemiological studies of weight variability, and not

the outcomes of behavioral treatment. There has been no direct evaluation of the long-term

health effects of dietary and behavioral treatment.

54

G. T. Wilson

Another argument in favor of rejecting an interpretation of their findings

as due to involuntary weight loss is that weight variability was associated

with cardiovascular disease but not cancer. The latter, more than the

former, would likely be associated with weight loss. Finally, it should be

noted that contrary to Garner and Wooleys (1991) suggestion that it is

weight cycling rather than obesity that constitutes the health hazard, Lee

and Paffenberger (1993) caution that their data in no way imply that those

obese persons should remain obese, since alumni in the top quintile of body

mass index were at significantly higher risk of mortality from all causes and

from coronary heart disease when compared with their counterparts in the

lowest quintile. However, weight loss or gain - which may be associated

with weight cycling - also may adversely affect longevity (p. 2049).

The scientific rationale for weight loss treatment is that it reduces

the health risks associated with obesity (National Institutes of Health

Consensus Development and Conference Statement, 1985). Garner and

Wooley (1991), however, question the health risks of obesity. Nevertheless,

the National Institutes of Health Technology Assessment Conference on

Methods for Voluntary Weight Control (1992) arrived at the following

conclusion: Being overweight can seriously affect health and longevity. It

is associated with elevated serum cholesterol, elevated blood pressure, and

non-insulin-dependent

diabetes mellitus. Excessive weight also increases

the risk for gallbladder disease, gout, coronary heart disease, and some

types of cancer and has been implicated in the development of osteoarthritis

of the weight-bearing joints (NIH, 1992, p. 1). Moreover, there is

impressive evidence that even modest weight loss can significantly reduce

health risks in obese people (Wadden & VanItallie, 1992). Willett (1992)

points out that even in the absence of abnormalities in blood pressure or

lipids, obesity cannot be regarded as a benign condition, because it is

predictive of such complications.

Binge eating

Garner and Wooley (1991) suggest that the dietary treatment of obesity

may also contribute to the development of binge eating. Two studies have

tested this hypothesis directly. In the first, Telch and Agras (1993)

assessed the frequency of binge eating episodes during a combined Very

Low Calorie Diet and behavioral weight loss program. Once the low

calorie formula diet ended and patients were reintroduced to food, 30%

of those who had been identified as non-binge eaters prior to treatment

reported binge eating episodes. Treatment did not increase binge eating

in those patients identified as binge eaters, however. In fact, 39% of these

patients ceased binge eating as a result of treatment. These preliminary

data indicate that strict dieting may trigger binge eating in some obese

Behavioral Treatment of Obesity

55

patients. In the second study, Yanovski and Sebring (in press) showed

that a standard VLCD program reduced the frequency and size of binge

eating episodes in obese binge eaters. There was no iatrogenic effect on

non-binge eaters.

A third study is also relevant in this context. Treating obese Type II

diabetic patients, Wing (1992b) compared the rates of dietary lapses

during behavioral treatment combined with either a VLCD (400 kcal)

or a balanced diet (100&1500 kcal). The two dietary programs did not

differ on either objective (intake of food 20% or more above daily calorie

goal) or subjective (patients perceptions that they had transgressed calorie

limits) lapses. A concern with the possible occurrence of binge eating

in obese patients in treatment should be part of a more general focus

on eating behavior. The issue is of theoretical and clinical significance.

Treatment programs need to monitor patients progress carefully to assess

this iatrogenic effect.

Adverse psychological

sequelae

The most extensively studied psychological consequence of diet-induced

weight loss has been depression. When all treatments of obesity are

considered, both increases and decreases in depression have been found. In

a comprehensive review of this literature, Smoller, Wadden, and Stunkard

(1987) argued that changes in depression following weight loss have been

primarily a function of the method used to assess psychological effects.

Related adverse reactions may have been the result of interpretive bias in

that they were ascertained through retrospective and subjective assessment

methods. Reported beneficial effects of weight loss have been shown

by more objective measures of outcome. Behavioral treatments have

produced reliable and significant decreases in depression and anxiety from

pre- to post-treatment.

Behavioral weight control treatments also result in other beneficial

short-term psychological effects. Body image dissatisfaction is decreased

and body size estimation is reduced (Dubbert & Wilson, 1984; ONeill &

Jarrell, 1992). Enhanced self-esteem, improved interpersonal functioning,

and increased marital satisfaction have also been reported. Although

the long-term psychological effects have received relatively little study,

Wadden, Stunkard, and Liebschutzs (1988) data indicate that treatmentinduced reduction in depression returns to baseline level at a three year

follow-up. Their patients reported that regaining weight had adverse effects

on their self-esteem and general happiness. In the absence of comparable

data from untreated obese individuals, it is difficult to interpret these

reports. Whereas the biological consequences of weight cycling have been

56

Ci. T. Wilson

studied in some detail (Brownell & Rodin, 1993; Wing, 1992a), the putative

psychological impact has been neglected.

Wooley and Garner (1991) argue that obesity treatment has several