Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

The Life Story PDF

Caricato da

sofijaTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

The Life Story PDF

Caricato da

sofijaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

The Life Story

Author(s): Jeff Todd Titon

Source: The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 93, No. 369 (Jul. - Sep., 1980), pp. 276-292

Published by: American Folklore Society

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/540572 .

Accessed: 16/05/2011 19:07

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless

you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you

may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at .

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=folk. .

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed

page of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Folklore Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal

of American Folklore.

http://www.jstor.org

JEFF

TODD

TITON

The Life Story*

A LIFESTORY IS, simply, a person's story of his or her life, or of what he or she

thinks is a significant part of that life. It is therefore a personal narrative,a

story of personal experience, and, as it emerges from conversation, its ontological status is the spoken word, even if the story is transcribedand edited

for the printed page. The storyteller trusts the listener(s) and the listener

respectsthe storyteller,not interruptingthe train of thought until the story is

finished. That is not to say the listeneris passiveas a doorknob;he nods assent,

interposes a comment, frames a relevant question; indeed, his presence and

reactionsare essentialto the story. He may coincidentallybe a folklorist, but

his role is mainly that of a sympatheticfriend.

This essay is directedto folkloristswhose fieldwork, like my own, involves

talking to people and finding out about their lives. My intention is to define

and develop an approachto the life story as a self-containedfiction, and thus to

distinguish it sharplyfrom its historicalkin: biography, oral history, and the

personalhistory (or "life history," as it is called in anthropology).

Among the dimensionsof folk culturewhich RichardDorson observedduring his 1968 field trip to Gary, Indiana,and East Chicago, was something he

called "personalhistory." In the 1970 articlewhich resulted, "Is There a Folk

in the City?" he told folklorists to cast aside worries over whether the personal history is a traditional oral genre, and urged them to collect the

"thousands of sagascreatedfrom life experiencesthat deserve, indeed cry for,

recording."' Dorson caught the documentaryspirit of the times. The following decade witnessed a rebirth of interest in the experiences of ordinary

Americans, especially blue-collar workers, racial and ethnic minorities, and

*

A slightly different version of this essay formed the basis of an illustratedlecture before the Graduate

Colloquium in Folklore and Folklife at the University of Pennsylvaniaon October 1, 1979. I am grateful

for their invitation and for their suggestions in the discussion which followed.

i Richard M. Dorson, "Is There a Folk in the City?" rpt. in Folklore:SelectedEssays(Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1972), pp. 67-68.

THE LIFESTORY

277

women. Not since the New Deal era was there such a burst of documentary

energy. Studs Terkel's books became best-sellers;Robert Coles's books influenced public policy; Theodore Rosengarten's life of black Alabama

sharecropper Ned Cobb won the National Book Award; professional

sociologists turned out monographson the lives and opinions of the so-called

silent majority;hundredsof oral history projectswere born at the local level,

thousandsof people were interviewed, and millions of pages of typescriptwere

produced.2 Folklore's contribution to the documentation decade, in the

popular mind, resides in the Foxfire concept of education, and the resulting

Foxfirebooks, now including five volumes.3

In the midst of all the documentation it is well to recall what Thoreau

wrote: "Much is published, but little is printed."4 Most of the published

documents appearto be life storiesbut are not. That is, they give the impression that someone is speaking about his life in his own voice, but in reality

someone else has muffled and distortedit. What appearsto be a person telling

a life story is usually an informant answering a seriesof questions. Then by a

common ruse the interview comes to masqueradeas a life story. The interviewer or an editor selects the relevant answers; arrangesthem according to

editorialpurposes,be they chronological,topicalor historical;smooths out the

talk for the printedpage; and then removesthe questions. This falsealchemyis

clear enough when one compares Terkel's writings with his tapes; it is a

brazen art in the hands of Coles (who does not use a tape recorder);5it is obvious in the two or three segments of each Foxfirebook given over to personal

narratives;and it is evident, also, in the relatively small number of personal

documents which professionalfolklorists have published.

The reason we transforminterviews into life stories on the printed page

without much uneasinessis that we habituallyfail to distinguish story from

history when the medium is talk. Dorson's choice of the phrase "personal

history" is illuminating, for he used it interchangeablywith the phrase "life

story" when recalling how he happenedupon examples of them: "Several

2

Studs Terkel's Division StreetAmerica (New York: Random House, 1967) was the first of four

volumes; Robert Coles's Childrenof Crisis(Boston: Little Brown, 1967) was the first of five; Theodore

Rosengarten, All God'sDangers(New York: Knopf, 1974).

3

The first five volumes, published by Doubleday & Co., appearedbetween 1972 and 1979.

Walden,chapter 4: "Sounds."

5 Interviewed Dick Cavett on a television

by

program I saw in Boston early in 1978, Coles said the tape

recorder made the people he spoke with nervous. He said he learned to catch language by watching

William Carlos Williams emerge from house calls and jot down his patients' phrases.

278

JEFFTODD TITON

memorablelife stories,"he wrote, "cameto my earswithoutprompting."6

As a good historian,Dorsonknowsthatstoryis not the sameas history.If he

sometimesconflatesthe two, it may be becausehis conceptof folk history

of oraltraditionsandpersonaldocuments,set in

relieson the transformation

the structuresof everydaylife, into the historyof the folk.7

is perhapsbest understoodthrough

The differencebetweenstoryandhistory

what CharlesOlson, that most historicalof poets, labeled"stance." Olson

stancestowardlife: fiction (story, including

identifiedtwo complementary

poetry); and history. In its root sense,facio, fiction is not a lie but a

"making"; whereashistory, istorin,is "found out." To Herodotus,the

Greekverbpoiein(fromwhich ourpoetderives)meant"to make," whereas

meant"to findout

the nounhistormeanta "learnedman"andthe verbistorin

for oneself."8A storyis made,but historyis foundout. Storyis languageat

play; historyis languageat work. The languageof story is chargedwith

power: it creates.The languageof historyis chargedwith knowledge:it

discovers.Storyis a literatureof the imagination;history,thoughit be imaginative,drivestoward fact. The generationof historianswho were my

teachersbelieved,alongwith R. G. Collingwood,thathistorywasa branchof

the humanities.So long as historyis humanistic,it is a complementof story;

but they arenot the sameandcertainlynot interchangeable.9

"The reallanguageof menin a stateof vividsensation"was how Wordsthe sourceof his own poeticdiction,contrastingit with

worth characterized

the languageof artificeusedby poetswho hadbeenlong out of touchwith

genuine human sympathy.10The romanticbaggage which accompanied

Wordsworth'srevolutionaryideasplaceda value on rusticlife which few

modernfolkloristswould publiclyembrace;nonetheless,his interestin the

commonman and womanof the countrysidewas chieflyan interestin the

renewingpowerof a naturallanguagethatarosefromdeeplyfelt, personalexperience.This, of course,is the languageof the life story,not the languageof

Dorson, "Is There a Folk," p. 67.

See Richard M. Dorson, "History of the Elite and History of the Folk," in Folklore:SelectedEssays,

pp. 225-259.

8

Charles Olson, The SpecialView of History,ed. Ann Charters (Berkeley: Oyez, 1970), especiallypp.

19-23.

7

Collingwood's views may be read in his The Idea of History(Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1948).

10Preface to

LyricalBallads(1805). The quoted phrase appearsin its second sentence.

THE LIFESTORY

279

history. It is particularlynot the language of history today, for increasingly

during the past twenty years the narrativemode of writing history hasbeen attackedfor its failureto meet adequatestandardsof scientificexplanation.Many

historians now believe that so-called covering-law explanations-that is, explanationsof specificevents by a generallaw which "covers" the specificconditions-are the only valid form of historicalexplanation. Whatever its value

in historical writing, this scientific criterion is irrelevant to explanation in

storytelling. Why it is irrelevantis best illustratedby an example, a life story.

The following life story is the religious conversion narrativeof blues singer

Son House, which he told to me in responseto my askingwhy he waited until

adulthood to become a blues singer. I have transcribedit verbatimfrom my

field tape:

When I was a kid, a youngster, a teen-a young teenagerand up like that I was more churchified. Then that's mostly all I could see into. Cause they'd had us go, we'd had to go to the

Sabbathschool every Sunday. We didn't miss goin to no Sabbathschool. We'd be into that

and then in this church there, some of the ones a little largerthan me and like that, and it come

time of year for em to run revivalmeetin. Some pastorcome to open up the revivalmeetin, oh,

for a week or more. [Coughs.] Well, we'd all be goin to the thing they call the mourners'

bench. Gettin on your knees, you know, and lettin the old folks pray for you. Yeah, and in a

couple of days or weeks, somebody'd come up, holler out they had something. They had

religion. They'd squall round man, go on. So they left me thataway I guess, oh

about, nearbout six or eight months sometime. I didn't fall for it becauseI, I figured they was

puttin on and I didn't want to be puttin on. I wanted mine to be real and so Ijust kept on until finally, [clears throat] the next session, I said, "Is there-this one time I'm just gon see

is-is any way to get this thing religion they goin round here talkin about, puttin on and goin

on." I prayed and prayed, commenced prayin, man, every night, workin in the field, and

plowin the mule and everything. Work all day hard, and go on home, whew, tryin to pray,

tryin to pray, and work. So, finally, I kept on like that until they come back home that night,

middle of the night after the pastor turned out. So I went on home. And I was livin down in

the lower part [of] the place from where my daddy an them stayed, down to my cousin's.

Went down there; I didn't want to be up there around the old folks. And man, I went out

back of the house a little bit, in this old alfalfafield out there. I had been scaredof snakes,

'cause snakeswould be bad in the summertime, you know, crawlin through them weeds and

things. But I wasn't studyin them snakes then. I'd say they better get out of the way if they

don't want to get their heads mashed off! [Laughs.] I went on. I was there in that alfalfafield

and I got down. Pray. Gettin on my knees in that alfalfa.Dew was fallin. And man, I prayed

and I prayed and I prayed and for wait awhile, man I hollered out. Found out then. I said,

"Yes, it is somethin to be got too, 'cause I got it now!" [Laughs.] Sure did. Went on back

there to that house and told my cousin Robert and all them bout that and went, walked about

two miles and a little better, and up to another white fellow's house, and woke him up and

told him all about it. We was workin for him, too. But I wouldn't carehow tough he was or

what not. "Get up out of that bed and listen to what I got to say." [Laughs.] He thought I

JEFFTODD TITON

280

was crazy! Yeah. Name was, we all called him Mister Keaton, T. F. Keaton. Yeah, I say,

"Oh yeah!" Found out better now.1

On hearingthis story, a doubtingThomasmight objectthat it containsa

hollow core;that the beforeandafterof conversionis described,but not the

momentitself.Someonewho hadundergonea similarexperienceandwas less

of an empiricistwouldperhapssaysucha demandwas philistine.But proofis

not at issuehere.Nor is it a questionof whetherthe religionSon Housewas

convertedto is a delusion.What is at issueis a humanbeingrecollecting,in a

state of vivid sensation,a criticalmomentin his life, and to a degreereexperiencingit by meansof storytelling.Coveringlaws statingconditionsunder

which conversionis probableoperatein an entirelydifferentdimension.A

sophisticatedreligiouscritiquemight scoreSon House for confusingan intenselyfelt experiencewith the validationof a worldview, but no criticcould

rob him of the memoryof his religiousconversion.His life story is not a

historicaldescription,and it does not obey historicallaws. It is a fiction, a

making,and, like all powerfulfictions,it drivestowardenactment.

OralHistory,andthePersonal

History

Biography,

Among the historicalkin to the life storyarebiography,oralhistory,and

life history).Any folkloristinterested

the personalhistory(or anthropological

of these

in the life storywoulddo well to becomefamiliarwith the procedures

historicalgenres,if only to avoidthem. Folkloristspracticingthesehistorical

genres,which of courseareperfectlylegitimatefolkloristicinterests,should,

on the other hand, understandwhy they cannotpretend,to themselvesor

others,that theirproductsarelife stories.

cameinto Englishwith Dryden,who in 1683definedit

The word biography

men'slives."12The biographical

as "the historyof particular

impulseis praise

for an exemplarylife, andso the publicfunctionof mostbiographyis didactic,

either implicitly or explicitly."3Modern standardsof professionalismin

1 Recorded in Minneapolis, Minnesota, May 8, 1971. A plastic soundsheet recording and my

ethnopoetic transcription are available in Jeff Titon, "Son House: Two Narratives," Alcheringa:

Ethnopoetics,NS, 2, No. 1 (1976), 2-6. A conventional transcriptionappearsin Jeff Todd Titon, Early

DownhomeBlues:A Musicaland CulturalAnalysis(Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1977), pp. 21-22.

The slight discrepanciesin the texts reflect changes in my understanding of House's diction over the

years.

12

Bobbs-Merrill,

3rd ed. (Indianapolis:

to Literature,

Quotedin C. Hugh Holman,ed., A Handbook

1972), p. 64.

13 See Robert

Gittings, The Nature of Biography(Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1978), pp.

19-21. I suppose another impulse must be curiosity about an allegedly scandalouslife.

THE LIFESTORY

281

biographical

writing, however,dictatethat the biographerowe his allegiance

not to his subjectbut the factsof his subject'slife. In Theory

Rene

ofLiterature,

Wellek explainswhy the biographeradoptshistoricalmethods:

The problems of a biographer are simply those of a historian. He has to interpret his

documents, letters, accountsby eye-witnesses, reminiscences,autobiographicalstatements, and

to decide questions of genuineness, trustworthiness of witnesses, and the like. In the actual

writing of biography he encounters the problems of chronological presentation, of selection,

of discretion or frankness.The ratherextensive work which has been done on biography as a

genre deals with such questions, questions in no way specificallyliterary.14

The biographer

is thusa historian,a life writeraimingto describeandexplain

the circumstances

of his subject'slife, personality,andinfluence.Yet because

his productis the record,sometimeseventhe story,of a life, the historicalimof dataavailableto the

aginationwill sometimescrawlout fromthe avalanche

modernbiographerandturnits subjectinto a palpablehumanbeing, usually

by giving him or her words to say. Boswell, the first modernbiographer,

catchesJohnson'spersonthroughhis conversationmore than anythingelse.

When we hearhim, then we know him, or at leastwe think we do.

A biographywhich announcesitself as the writer's accountof someone

else's life is not likely to be confusedwith the life storybecausethereis no

questionaboutwho is the author.The questionof authorshipis centralto the

problemsof oral historyand the personalhistory,but the lines are clearly

drawn in biography.Biographyper se has not had much of an appealto

in recentyears,when the mainlines of researchand

folklorists,particularly

have

concentrated

in collection,annotation,andanalysisof texts; in

writing

folkloristictheory;in materialculture;andin the application

of folkloreto the

concernsof local, tradition-bearing

groups.s1

Oralhistory,likebiography,proceedsfroma historicalratherthana fictive

stance.Likebiography,its overridingconcernis with factualaccuracy.Unlike

biography,its focus is chieflyon events,processes,causesandeffectsrather

thanon the individualswhose recollectionsfurnishoralhistorywith its raw

data.A recentdevelopment,oralhistorydatesfromjust afterWorldWar II,

when Allan Nevins of ColumbiaUniversityconvincedhis institutionto

becomea repositoryforinterviewswith the men-and in mostcasestheywere

men-who had"madehistory."Historiansweretrainedto asklawyers'questionsin aneffortto get evidencefromlivingwitnesses.By 1974morethan300

14Rene Wellek and AustinWarren,

3rd ed. (New York: Harcourt,Braceand

Theoryof Literature,

World, 1956), pp. 75-76.

15But see the

Scott:TheWoodsmanbiographical

analyticalstudiesby EdwardD. Ives,particularlyJoe

(Urbana:Universityof IllinoisPress,1978).

Songmaker

282

JEFFTODD TITON

institutions in the United States housed more than 500 different oral history

projects.16

Not all the projects in oral history are elitist. Possibly in response to the

climate of the "new" social history, oral history projects now sometimes

focus on the experiencesof ordinaryAmericans.When RichardDorson called

for a folk history built up from the personal histories whose collection he

urged, he could not have anticipatedthe local oral history projects that were

springing up even as he was writing. Yet his assessment that professional

historianswould not be the ones to undertakefolk history projectsis still correct.'7 The new socialhistory's emphasisupon quantificationand its distrustof

literary evidence drive historiansinto harderand harder "scientific" lines in

order to maintain professionalrespectability.18Charts, graphs, tables, Greek

symbols, and a variety of English sentences reduced to laws expressed by

mathematicalequationsnow stareout from the pages of the historicaljournals,

while personaldocuments are left far behind in the quantitativeanalysis.

Scientism of this sort has not yet appearedamong folk-culturallyoriented

oral histories, but they suffer from other problems. The AppalachianOral

History Project, for example, based at Alice Lloyd College in eastern Kentucky, began interviewing residentsof central Appalachiain 1971. In 1977 it

An OralHistoryand introducedthe book as a "social

publishedOurAppalachia:

history"which "has providedthe opportunity to let residentsof the region tell

their own story"(my italics).19Here is anotherillustrationof the confusion of

history with story. This oral history is reallythe productof highly directedinterviews, and we know this because the editors had the good sense to print

some of the questions. When we come across a leading question in Our Appalachia,such as "What was it about John Wright that made his word law

among the children?" (p. 60), we know we are not listening to a story. Instead, we are reading the result of a collaborative venture between the

historiansand the informants.This collaborationis the natureof oral history,

as Edward D. Ives recognizes in his introduction to Argyle Boom, an oral

history of log transportationon the Penobscot River:

For textbooks in collecting and editing oral history, see, for example, OralHistory:FromTapeto Type

andEditingOralHistory

(Chicago: American LibraryAssociation, 1977), and Willa K. Baum, Transcribing

(Nashville: American Association for State and Local History, 1977).

16

17

Dorson, "History of the Elite," pp. 239-241.

18 For a review, see Lawrence

Veysey, "The 'New' Social History in the Context of American

Historical Writing," Reviews in AmericanHistory,7 (1979), 1-12.

19 Our

Hill and Wang, 1977), p. 3.

Appalachia,ed. LaurelShackelfordand Bill Weinberg (New York:

THE LIFESTORY

283

The descriptionsmen like Ernest Kennedy and Alphonse Martin gave came in responseto the

questions the students put to them, and new questions grew out of their responses. Oral

history interviews are the joint creations of two people, interviewer and interviewee. .. .20

In oral history the balanceof power between the informantsand historianis in

the historian'sfavor, for he asks the questions, sorts through the accountsfor

the relevantinformation, and edits his way toward a coherent whole-as, for

example, Ives quite properly did in Argyle Boom. But in the life story the

balancetips the other way, to the storyteller,while the listener is sympathetic

and his responses are encouraging and nondirective. If the conversation is

printed, it should ideallybe printedverbatim,or if presentedon film it should

ideally be unedited.

Folk-culturaloral histories often sharea curious editing techniquewhich is

worth comment here. It may be observedin the aforementionedoral histories

and the Foxfirebooks. The editors do not hesitateto splicetogether sectionsof

one or more interviews outside the chronologicalorderof the telling. They do

not hesitate to delete sections of interviews nor words from the informants'

sentences.Yet they seem to believe that by bracketingwords which they supply for continuity, thereby distinguishing them from words which the informants actually spoke, they are remaining faithful to their informants'

language. This bracketing procedureseems to me to pretend to a degree of

scrupulousnessthat is unjustified,given the editoriallibertiestaken in excision

and rearrangement.The false claims that result-and I am aware of the problem becauseI have been one of the claimers21-cansometimeseven go so far as

to convince the editor that what resultsis what the informanthad in mind and

would have said if he had been more articulate.

Of the historicalkin to the life story, the personalhistory is the most problematic, for it is a written account of a person'slife basedon spoken conversations and interviews. The anthropologicalliteratureis filled with hundredsof

these personal histories, called life histories, while folklorists and

ethnomusicologistshave producedperhapstwo dozen. In his 1965 treatiseon

the anthropologicallife history, L. L. Langnessviews the enterpriseas essentially biographical rather than autobiographical, and in this he is surely

correct.22In his review of the literaturehe acknowledgesthat anthropologists

20

21

Argyle Boom, ed. Edward D. Ives, NortheastFolklore,17 (1976), 18.

See FromBluesto Pop: The Autobiography

of Leonard"BabyDoo" Caston,ed. Jeff Titon (Los Angeles:

John EdwardsMemorialFoundationSpecialSeries,No. 4, 1974), p. 1.

22

L. L. Langness, The Life Historyin Anthropological

Science(New York:Holt, Rinehart and Winston,

1965), pp. 1-7.

284

JEFFTODD TITON

collect life historiesprimarilyto obtaininformationabout culture,not individuals.23

Given its orientationtowardculture,it is no wonderthat the

typicallife history strips the individualof his voice. Langnessadvisesthe

would-becollectorthat "Lifehistorymaterialsareseldomthe productof the

informant'sclearlyarticulated,expressive,chronologicalaccountof his life,"

without stoppingto ask whetherthat might be the fault of the collectors'

close questioningand frequentinterruptions,or perhapsthe result of difficultiesin translationfrom the nativelanguage.Langnesscontinues:"This

meansthat a certainamountof editingmust be done . . . particularly

when

commercialpublicationis concerned."24

In otherwordsit is the pressureof

the marketplace

whichforcesthe anthropologist

to takethe rawmaterialfrom

turn

a

and

it

interviews

into

biographywhich pretendsto be an

choppy

is

as

it

But

just likely that thesepressuresreposein his colautobiography.

leagues, his readers,and he himself, all of whom might find verbatim

of the interviewstedious,unrewarding,andat timesembarrassing.

transcripts

My positionwith regardto life historiesis similarto but not so radicalas

LindaDegh's. She writes that "The anthropological

conceptof life history

collectionis unacceptable

to the folklorist,basicallybecauseof the lackof accurateandexactingmethodsof recordingandpublicationwhich reflectsthe

lackof interestin humancreativitymanifestedin the formulationof the narrative."25That creativity cuts both ways, for the life history narrativeis as

much the creation of the anthropologist as of the informant.26But the anthropological concept of life history collection cannot always be "unacceptable" to the folklorist. Sometimesit is impossibleto obtain a life story, either

because of poor rapport, or because the informant is unwilling, taciturn by

nature, or incapableof a sustainednarrative.Yet the life history of an important traditionbearerwhose life story cannot be obtainedwill surelycontribute

folk-cultural information. The anthropologicalliterature contains some life

histories, moreover, which are products of sympatheticconversationsamong

friends; and they usually can be told from the rest because, Langness not-

23

Ibid., pp. 8-12.

24

Ibid., p. 48.

Linda Degh, People in the TobaccoBelt: Four Lives (Ottawa: National Museum of Man, Canadian

Centre for Folk Culture Studies, Paper No. 13, 1975), p. viii.

25

A view similar to my own is expressed in Gelya Frank, "Finding the Common Denominator: A

Phenomenological Critique of Life History Method," Ethos, 7 (1979), 68-94. I am grateful to Barbara

Tedlock for pointing this out and showing me Frank's essay.

26

THE LIFESTORY

285

withstanding,the informantsare articulateand expressivein the context of

friendship.27

Folkloristshavenot publishedas largea proportionof theirinformants'perhave.But sincethe personalhistoryis closer

sonalhistoriesas anthropologists

to the life storythanbiographyor oralhistoryis, folkloricpublications

in personalhistory,howeversmalltheirnumber,meritattentionhere. I shallconcentrateon easilyaccessible,English-language

examples.In this genre,then,

we maynote the earlyinfluenceof the Lomaxes:JohnLomaxwas the guiding

forcebehindthe WPA slavenarrative

collectionandthelifehistoriespublished

in TheseAreOurLivesandSuchas Us,28whileAlanLomaxrecorded

JellyRoll

Morton'slife story for the Libraryof Congressin 1938. The resultinglife

Roll,exhibitsunusuallystrongtensionbetweenstoryand

history,MisterJelly

history.Mortonwas a splendidnarratorandLomaxknewit: "To everyquery

his responseswere so instantandso vivid with time andplaceandwho was

thereandwhat they said,thatI knewJellywas seeingit in fancyif not in actual recollection."29But much of what Morton said was extravagant,and in

writing his book Lomax was torn between his interest in getting the facts

about the birth of jazz and this incredibleand bizarrerelic who was desperate

to tell his boastful story. Lomax finally decidedit was personalhistory that he

was hearing: "That hot May afternoonin the Libraryof Congress a new way

of writing history began-history with music cues, the music evoking

recollection and poignant feeling-history intoned out of the heart of one

man, sparklingwith dialogue and purplewith ego" (p. xiii). MisterJellyRoll is

an extraordinarymix of fact and fiction, life story, personalhistory, and oral

history, served up by a folklorist whose creativeenergies were a sympathetic

match for his informant's.

The majority of folkloric personalhistories have taken musiciansfor their

subjects. My own published attempts in this genre have been no better than

most. I miscalled the personal histories of Lazy Bill Lucas and Baby Doo

Caston autobiographies,put their statements into chronological order, and

27

See, for example, Sidney Mintz, Workerin the Cane (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1960), and

Son of Old Man Hat: A Navaho Autobiography

Recordedby WalterDyk (1938; rpt. Lincoln: University of

Nebraska Press, 1967).

28

Norman Yetman, Life Under the "PeculiarInstitution"(New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston,

1970), p. 348. TheseAre Our Lives (1937; rpt. New York: Norton, 1975); Suchas Us: SouthernVoicesof

the Thirties,ed. Tom E. Terrill and Jerrold Hirsch (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press,

1978).

29Alan Lomax, Mister

Jelly Roll (New York: Grossett and Dunlap, 1950), pp. 241-242.

286

JEFFTODD TITON

then deleted my questions.30A few years ago when I had second thoughts

about the standardeditorialprocedure,I decided to publish Son House's personal history as a verbatimtranscriptof our conversations.31Robin Morton's

life of John Maguire is similarlya personalhistory in the words of the informant, and the product of a conversationamong friends. Here is what he says

about his nondirectiveinterviewing method, and it is good advice:

First of all I knew John very well before I ever startedthis project. I discussedwith him what I

wanted to do and he agreed to "have a go." So we sat down with an empty tape on the

recorderand began. I first asked a very general question-"Tell me about your early life." I

always asked general questions except when I wanted something explained in more detail.

Once I had asked a question I sat quietly and let John talk. Even when he seemed to have

finished I sat with an expectant look in the hope that he would continue, as he often did. Only

when he seemed to have nothing more to say did I continue with a subsidiaryquery, or go on

to a new areaaltogether. To the extent that I asked questions at all the "story" probablytells

us much about me and my interests as it does about John. It is difficult to see how one

sidesteps such a danger completely.32

One cannot sidestepsuch a dangerso long as there is an audiencefor the story

in the anticipatorymind of a storyteller who conceives of his task as communicatingwith that audience.But that only means that unless the informant

is talking to himself, what seems a "danger" is inherent in any conversation,

and the folklorist therefore should pay attention to how the talkers' ideas

about who their audienceis shapestheir conversation.This aspectof the relation of text and context has of course been the focus of a great deal of recent

theory from folklorists who conceive of folklore as "communication" based

on "performance." But despite Morton's awarenessof Maguire's story as a

collaborationbetween the two of them, he followed the accepted historical

editing practice and rearranged Maguire's answers according to topic,

whereupon he deleted his questions and departed, ghostlike, from the text.

The resulting personal history serves mainly as a vehicle for introducing the

songs in Maguire's repertoire,whose texts and tunes are printed. In a similar

vein is Roger Abrahams'A SingerandHer Songs,a book that contains important informationabout Almeda Riddle's song sourcesand her aestheticcriteria

as well as the texts and tunes of a large portion of her repertoire.Although the

Titon, FromBluesto Pop. The brochure notes to Lazy Bill Lucas,12" LP, Philo Records 1007 (North

Ferrisburg, Vt., 1974) contain Lucas' personal history.

31

Jeff Titon, "Living Blues Interview: Son House," Living Blues, No. 31 (Mar.-Apr. 1977), 14-22.

30

Robin Morton, Come Day, Go Day, God SendSunday(London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1973),

xii.

p.

32

THE LIFESTORY

287

book is in Riddle'sown words,Abrahamscorrectlyclaimsthatit centerson

"the waysin whichfolklorehaspersisted,emphasizingthe hows andwhys of

and transmission."33

We learnaboutGrannyRiddle'spersonal

performance

time

from

to

time

as

insofar

it bearson hersongs,but the editedprodhistory

uct is not meantto be a life history;andat timesone feelsin it the cumulative

effect of GrannyRiddle introducingher entire song repertoireat a folk

festival.

Two folkloricpersonalhistorieswhich do not concernthemselveswith

musiciansarefocusedon workas a meansof individualidentity.MeandFannie

is billedas the "oralautobiography"

of MainewoodsmanRalphThornton.34

(Fannie,his wife, is seldomon centerstage,but herpresenceis felt.) Resulting

from tape-recorded

conversations,it was editedby the interviewer,Wayne

Reuel Bean,who chronologizedand spliced,deletedhis questions,and then

suppliedcommentsfor continuity.If it deservesto be calledanautobiography,

it is becauseThorntonhimselfselectedthe materialfrom the interviews;and

this selectiongave Thorntona greaterdegreeof controlthanmost personal

historyinformantsareallowed.Bestregardedas a memoir,MeandFannieis an

unusuallyexternalaccount,with almostno referenceto Thornton'sinnerlife.

of hisworkadaylife,

Pageafterpagegoesby in whichhe recallsthe adventures

as

a

it

and

comes

as

a

the end of his

toward

cook;

mostly

surprisewhen,

chronicle,he casuallyobservesthat he does not like cooking.35Anotherpersonalhistoryconcernedmainlywith work is BruceJackson'sA Thief'sPrimer,

but here the accountis moreintrospective,andJackson,who in editingdid

not delete all his interviewer'squestions,shows himselfresponsiveto the

ironies of criminalpride and self-respectwhich permeatehis informant's

recollections.36

Evenwhen theyaremistakenlypresentedas stories,biography,oralhistory,

and the personalhistory sharea historicalratherthan fictionalbase. The

editingprocedures,the datagathering,the researchplans,and the resulting

publicationsare orientedtowardfactualaccuracy.The historicalmethodis

well suited to the folklorist seeking folk-culturalinformation.But it

sometimeshappensthat in doing fieldworkwe folkloristsfind ourselves

caughtup with the livesof ourinformants,not so muchbecauseof what they

33

A Singer and Her Songs, ed. Roger Abrahams (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State

University Press,

1970), p. 147.

34 Me

35

36

and Fannie,ed. Wayne Reuel Bean, NortheastFolklore,14 (1973).

Ibid, p. 73.

Bruce Jackson, A ThiefjsPrimer(New York: Macmillan, 1969).

JEFFTODD TITON

288

cando, or what theyknow, but who theyare.In theirstoriesof personalexperience,they try to tell us.

TheLife Storyas a Fiction

Folkloristshavepublishedfew personaldocumentssensitiveto the fictive

situationin whicha persontellsthe storyof hisor

aspectsof the conversational

her life or a significantportion of it. I have arguedthat most personal

documentsin which the informantsupposedlyspeaksin his or herown voice

arehistoricalin nature,the folkloristdestroyingby designor accidentthe ficOne exceptionis Linda

tive potentialinherentin the originalconversations.

a

verbatim

Belt:

Four

Tobacco

the

in

Lives,

publicationof fourlife

Degh's People

stories,with briefanalysesof the stories,storytellers,andtheirbackgrounds.37

herreinterchangeably,

AlthoughDegh usesthe termslifestoryandlifehistory

inher

and

fieldandpublicationmethods

jection of standardanthropological

of converled herto publishthe transcripts

terestin the individualstorytellers

sationsin whichtheytoldher,andusuallya few friendsandfamilymembersas

as Hungarianimmigrantsin Canada.Reviewing

well, abouttheirexperiences

this book in FolkloreForum,Larry Danielson pointed out that "On

occasion... the informant'sremarksindicatethata questionhasbeenasked,

though not includedin the transcription,"and that probably"certain

andpublication.Such

betweentranscription

disappeared

speaker'sdesignations

detailsmaybe trivial,but theyassumeimportanceif we areto relyon texts as

of the

Now of coursethe meretranscription

uneditedand authoritative."38

at the

decide

must

for

one

spokenwordonto theprintedpageinvolvesediting,

very least how to render it, in prose or ethnopoetictranscription,for

example.39And even if one chooses the conventionalrenderingin prose

one must edit to the extent of insertingpunctuation,which, as

paragraphs,

anyonewho haseverdoneit knows, canleadto difficultdecisionsaboutemphasisand meaning.This aside,I take it that sincetherewas no reasonfor

them, the omissionsin Degh's publishedtranscriptwere editorialaccidents,

pureand simple.

life stories in the folkloric

How, then, is the dearthof unadulterated

literatureto be explained?The most insidiousreason,I haveargued,is the

37

See note 25.

38

FolkloreForum,9 (1976), 172-173.

39 For examples of ethnopoetic transcription,see Dennis Tedlock, FindingtheCenter(New York: Dial,

1972). See also the journal Akheringa:Ethnopoetics.

THE LIFESTORY

289

conflationof story with historyand the transformation

of the one into the

other. KennethGoldstein'sA Guidefor Field Workersin Folkloreis an interestingcasein point.Thoroughandusefulthoughit is, it exhibitstheclassic

difficultiesof approaching

fictionas if it were, or ought to be, history.Using

the frameworkof culturalanthropologyto approachthe "data" of folklore,

Goldsteinwrites:"One of the most importantcontributionswhich the field

workercanmaketo folklorestudiesis the gatheringof dataforusein personal

documents.As they applyto the fieldof folklore,suchdocumentsmay

history

be definedas thestoryof thelife(or somepartof it) of anindividualfolkloreinformant.The datafor thesedocumentsareobtainedmainlyby the useof interview methods... ."40(my italics).To be fair,Goldsteinelsewhereis sensitive

to the advantages

of a fictionalstancewhen he advocatesverbatimpublication

of interviewswhen the informantdescribesin detaila topicor activityof interestto folklorists,andwhen he revealshis preference

for the nondirective

interview.41Still, the Guide'sfolk-culturalorientationdominates,and the

would-befield-workercomesawaywith the clearimpression

thatlifestoriesof

traditionbearersought to be treatedas historicaldocuments.

Asidefromthe conflationof storyandhistory,othercausesmaybe citedto

asfichelpexplainthe scarcityof folkloriclife storiespresentedandinterpreted

tions. One is that folkloristsarebetterreadin contemporary

anthropological

verbal-arttheorythanin contemporary

literarytheory.Anotheris the debate

over the folkloristiclegitimacyof the personalexperiencestory.42Anotheris

the hit-and-run

to fieldwork,a methodbasedon the assumptionthat

approach

folkloreconsistsof items to be collectedon field trips.Armedwith findingaidsandeagerfor data,the hit-and-runfield-workeris like the botanistwho

Under

bringsbacka greatvarietyof specimensfor analysisandpreservation.

theseconditionsof efficiency,any life storiescollectedarelikelyto be mined

for traditionalelements,then storedon reelsof tapeuntil they areerasedfor

futurefield trips. Fortunately,this type of field collectingis on the wane,

thoughwhy someof us acceptit from-even encourageit in-our studentsis

beyondme. But as folkloristsincreasinglycome to developfriendshipswith

their informantsover severalmonths', even years', time, the word "informant" becomesinappropriately

impersonal.As thosefriendships

deepen,the

Kenneth S. Goldstein, A Guidefor Field Workersin Folklore(Hatboro, Pa.: Folklore Associates,

1964), p. 121.

40

41

42

Ibid., pp. 123-124, 127.

See, for example, the specialdouble issue of theJournalof theFolkloreInstitute,14:1-2 (1977), which

is devoted to the personal experience story.

290

JEFFTODD TITON

opportunities for life story conversationsincrease. Seeking cultural information, the folklorist is likely to conceive of these conversationsas life history.

But if he is interestedin his friendas a person, and what it is that makeshim or

her a traditionbearer,he will look to the life storyas an expressionof personality and self-conception-the who and why ratherthanjust the what and how

of his friend's life.

Personalityis the main ingredientin the life story. It is a fiction,just like the

story; and even if the story is not factuallytrue, it is always true evidence of

the storyteller'spersonality.43The most interestinglife storiesexpose the inner

life, tell us about motives. Like all good autobiography,as opposed to mere

chronicling, the life story's singularachievementis that it affirmsthe identity

of the storytellerin the act of the telling.44The life story tells who one thinks

one is and how one thinks one came to be that way.

The naive listener might assumea life story to be a truthful, factualaccount

of the storyteller's life. The assumption is that the storyteller has only to

penetratethe fog of the past, and that once a life is honestly rememberedit can

be sincerelyrecounted.But the more sophisticatedlistenerunderstandsthat no

matter how sincere the attempt, rememberingthe past cannot renderit as it

was, not only becausememory is selective, but becausethe life storytelleris a

different person now than he was ten or thirty years ago; and he may not be

able to, or even want to, imagine that he was differentthen. The problem of

how much a person may change without losing his or her identity is the

greatestdifficultyfacing the life storyteller,whose chief concern, afterall, is to

affirm his identity and account for it.45So life storytelling is a fiction, a making, an orderedpast imposed by a present personalityupon a disorderedlife.

"I have changed

Yeats acknowledged in the preface to his Autobiographies,

nothing to my knowledge, and yet it must be that I havechangedmany things

without my knowledge."46We do not turn to Yeats's autobiographiesif we

want to know the facts of Yeats's life; we turn to them if we want to know

Yeats.

We can learn much from life stories. We can learnhow the traditionbearer

thinks of himself, and why he or she continues to make chairsor play the fid43

HarvardUniversityPress,1960),p. 1.

SeeRoy Pascal,DesignandTruthinAutobiography

(Cambridge:

44 See Patricia

45

46

Meyer Spacks, Imagininga Self (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1976), p. 1.

See Spacks, p. 28. Her analysis of autobiography as a genre is outstanding.

Preface to Reveriesover Childhoodand Youth (1914), in The Autobiographyof William Butler Yeats

(New York: Collier Books, 1965).

THELIFESTORY

291

die or preachas the Spirit moves. What is it about this person, we ask, that

makeshim an artistin the face of all the pressuresto stop? What makeshim an

exceptionalartist?Obviously his self-conception,who he thinks he is, is greatly responsiblefor what he does. We get behind the mere facts of his life, the

historicaldata, when we let him tell his story. So conceived, the life story need

not be "used" for folk-culturalinformationor as a "specimen" of oral performance or as "data" for oral history.

The life story need not be "used" for anything, becausein the telling it is a

self-sufficientand self-containedfiction. Fictions go on all the time, as Gertrude Stein pointed out: "I do not cannot believe that anything is or can be

more interesting than the fact that everybodyis always telling everything and

that anybody can in their way go on listening or not go on listening. But

everybodycan feel about telling and about listening like that. Anybodycan."47

We arecurious, and the life story is intrinsicallyinteresting. If not, we do not

listen. If it is interesting and we do listen we are moved with pleasure.Stein

also wrote that, "If you live a daily life every minute of the day the description

of that daily life every day must be moving, it must fill you with complete

emotion, and it must at the same time be soothing."48The life story told to a

sympathetic listener is a fiction complete in itself. The trouble with most

poets, Wordsworth wrote, was that they could not fix their gaze steadily

upon their subject.49They jumped away too quickly, classifiedit, transformed

it, used it. Let us not use the life story too quickly;let us know it first. Charles

Olson had this in mind when he wrote:

... that a thing, any thing, impinges on us by a more important fact, its self-existence,

without referenceto any other thing, in short, the very characterof it which calls our attention to it, which wants us to know more about it, its particularity.That is what we are confronted by, not the thing's "class," any hierarchy,of quality or quantity, but the thing itself,

and its relevanceto ourselveswho are the experienceof it (whatever it may mean to someone

else, or whatever other relations it may have).50

An approachto the life story which recognizes its validity as a fiction, quite

47

GertrudeStein,Narration:FourLectures(Chicago:Universityof ChicagoPress,1935), p. 35.

48

Ibid., pp. 4-5.

"I haveat all timesendeavoured

to look steadilyat my subject,"wrote Wordsworthin the 1805

of concreteexperience,

prefaceto LyricalBallads,implyingthathe took his ideasfromcloseobservation

not fromliteraryconvention.

49

50 Charles

Olson, "HumanUniverse,"in Human Universeand OtherEssays,ed. DonaldAllen(New

York:GrovePress,1967), p. 6.

292

JEFFTODD TITON

apartfrom its value as a historicaldocument, places it squarelyin the human

universeabout which Olson was writing, a universewhich is enlarged,even as

we are enlarged,by the complementarystancesof finding out and making, of

history and fiction.

Tufts University

Medford,Massachusetts

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Book of ShadowsDocumento2 pagineBook of Shadowskrystalkamichi909633% (3)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The English Reformation and The Evidence of FolkloreDocumento29 pagineThe English Reformation and The Evidence of FolkloreLuis FelipeNessuna valutazione finora

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Morgenstern's Guide To AlchemyDocumento15 pagineMorgenstern's Guide To AlchemyMarkus WallNessuna valutazione finora

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- IKSPResearch Agenda UPDil Conf Dec 2012Documento54 pagineIKSPResearch Agenda UPDil Conf Dec 2012Suzaku LeeNessuna valutazione finora

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Indonesian Folktales World Folklore Series by Murti BunantaDocumento7 pagineIndonesian Folktales World Folklore Series by Murti BunantaMiyu Hanata0% (1)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Philippine Oral Traditions Theory and PracticeDocumento22 paginePhilippine Oral Traditions Theory and PracticeChem R. PantorillaNessuna valutazione finora

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Chapter 1 NotesDocumento3 pagineChapter 1 Notesapi-356650705Nessuna valutazione finora

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Tugas B.ingDocumento10 pagineTugas B.ingVivi FebriyantiNessuna valutazione finora

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Borat The TricksterDocumento12 pagineBorat The TricksterNicole Smythe-JohnsonNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan Done 1Documento53 pagineLesson Plan Done 1api-428694239Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

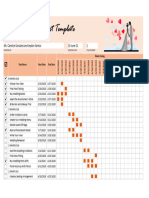

- Wedding Gantt Chart Template TemplateLabDocumento1 paginaWedding Gantt Chart Template TemplateLabqueen07Nessuna valutazione finora

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Niall Brigant Family Tree6Documento6 pagineNiall Brigant Family Tree6True Blood in DallasNessuna valutazione finora

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Evolution of DanceDocumento6 pagineThe Evolution of DanceAvegel Dumagat AlcazarenNessuna valutazione finora

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Aithihyamala: Translating Text in Context: KeywordsDocumento18 pagineAithihyamala: Translating Text in Context: KeywordsAnjanaSankarNessuna valutazione finora

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- School: Rizal High School Teacher: Mary Grace D. Santos Grading Period: 2 Grading Period Learning Area: ENGLISH Grade Level: 8 Date: September 2, 2019Documento4 pagineSchool: Rizal High School Teacher: Mary Grace D. Santos Grading Period: 2 Grading Period Learning Area: ENGLISH Grade Level: 8 Date: September 2, 2019Mary Grace SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Pre-Colonial LiteratureDocumento8 paginePre-Colonial LiteratureDana JoisNessuna valutazione finora

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- KamalaDocumento28 pagineKamalaPunnakayamNessuna valutazione finora

- Phyllis Galembo MaskeDocumento4 paginePhyllis Galembo MaskeLe Jete MarkerNessuna valutazione finora

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Sheekooyin III - Axmed Cartan XaangeDocumento59 pagineSheekooyin III - Axmed Cartan Xaangegaardi100% (1)

- Oral-Written Nexus in Bengali Chharas Over The Last Hundred Years: Creating New Paradigm For Children's LiteratureDocumento37 pagineOral-Written Nexus in Bengali Chharas Over The Last Hundred Years: Creating New Paradigm For Children's LiteratureLopamudra MaitraNessuna valutazione finora

- (Final) CAS 280 - CHARACTERIZING HIGAONON ETHNOMUSICDocumento14 pagine(Final) CAS 280 - CHARACTERIZING HIGAONON ETHNOMUSICJane Limsan PaglinawanNessuna valutazione finora

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- 5 6280298216130873256Documento2 pagine5 6280298216130873256Bobde dadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Iranian NightsDocumento4 pagineIranian NightsNaveed Malik100% (2)

- KENNETHDocumento6 pagineKENNETHPrince AntivolaNessuna valutazione finora

- BELL, Desmond - Found Footage Filmmaking and Popular MemoryDocumento16 pagineBELL, Desmond - Found Footage Filmmaking and Popular Memoryescurridizo20Nessuna valutazione finora

- Integrative Values of Folktales Igbo Folktale ExampleDocumento7 pagineIntegrative Values of Folktales Igbo Folktale ExampleInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Dragons Across Chinese, European, and Korean CulturesDocumento11 pagineDragons Across Chinese, European, and Korean CulturesNasir KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Grimm Book (Great Books)Documento3 pagineGrimm Book (Great Books)julieta fabroNessuna valutazione finora

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Essays in Applied Psycho-Analysis (Vol. II) - E. Jones PDFDocumento402 pagineEssays in Applied Psycho-Analysis (Vol. II) - E. Jones PDFSandra LanguréNessuna valutazione finora

- L3-Class Presentation-Creative Writing - Writing Fairy TalesDocumento46 pagineL3-Class Presentation-Creative Writing - Writing Fairy TalesPlanetSparkNessuna valutazione finora

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)