Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Discussion 2 TG Athirah

Caricato da

Anita VkTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Discussion 2 TG Athirah

Caricato da

Anita VkCopyright:

Formati disponibili

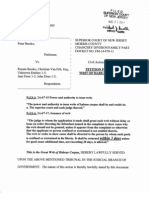

TENGKU ATHIRAH BINTI TENGKU AZHAR

A146465

QUESTION 1

Argument for Bersih:

The absence of specified period in the search warrant would raise

doubt as to the originality of the evidence tendered since there

could be a possibility of planting of evidence at the search place.

Further, it is immaterial whether such evidence is obtained illegally

or otherwise. As such, in in Wong Liang Nguk v PP, the appellant

was convicted of assisting in carrying on a public lottery contrary to

section 4(i)(c) of the Common Gaming Houses Ordinance. The

charge was that, she was knowingly carrying in a motor car, of

which she was the sole occupant, a number of books containing the

records of stakes relating to 1000 character lottery. The evidence

against the appellant consisted of three books which the police had

seized from her possessions when he stopped and searched her car

such a search was clearly unlawful because the police officer was

not authorised to do so under the Common Gaming Houses

Ordinance.

The judge held that the fact that the evidence is unlawfully

obtained will not affect its admissibility. If the police officer had no

authority to search then no doubt he would have been open to some

sort of civil action, but the question of his authority to search is

completely irrelevant to the admissibility of the evidence. Also, in

the landmark case Kuruma v The Queen, the appellant was

convicted of being in unlawful possession of 2 rounds of ammunition

contrary to Regulation 8A(1)(b) of Emergency Regulations, 1952. He

was sentenced to death. The issue was whether the evidence of

possession of ammunition had been illegally obtained. The court

held that the test to be applied in considering whether the evidence

is admissible is whether it is relevant to the matters in issue. If it is,

it is admissible and the court is not concerned with how the

evidence was obtained.

Therefore, pertaining to the facts, the failure on the part of the

prosecutor to ensure that the search warrant specifies the time of its

enforcement would raise doubt on the evidence tendered, since this

would cause prejudice to Bersih because the duration from 4 th to

15th July is deemed to be long enough for the police inspector to

plant any evidence at the search place. Plus, even if Bersih is

charged for an offence of retaining stolen property under the Penal

Code, the cases had shown that although the evidence was

unlawfully obtained, the court would not be concern with that so

long as it is relevant.

Argument against Bersih:

Generally, provisions of search warrants can be found under section

54 until section 64 of the CPC. Section 54 mentions that a court may

be issued if it has reason to believe that a person will not produce

the property or document when summoned, if it is not known to be

in the possession of any person and if a general search will serve

the purpose of justice or of any inquiry, trial or other proceeding.

Further, section 56 of CPC provides that a magistrate may issue a

warrant if upon information and after such inquiry as he thinks

necessary, he has reason to believe that anything regarding the

offence or the evidence/thing may be found in any place. Section 57

provides for the form of search. One of its requirements is to specify

the period of how long the search warrant would be in force.

Nevertheless, despite this general rule, the judge in the case of Lam

Chiak v PP states that the paper does not state what is the

reasonable number of days to be in forced however it must be

subject to one limitation, it must be reasonable. What is reasonable

would depend on facts of case. The court emphasized that it is

directory and not mandatory to have the number of days in the

warrant. In the case, the warrant was valid when it was issued and

remained valid for a reasonable number of days, notwithstanding

that such number of days was not stated therein. Thus, pertaining to

the facts, Aman, the police inspector was justified in conducting the

search warrant at the premise although it did not specify the time it

shall remain in force as required by the provision, because the

period from 4th to 15th July would still be considered as reasonable,

as in the case mentioned.

QUESTION 2

The issue is whether Mary has to abide by ASP Lilys request, which

is for the recording of her statement. Basically, section 112 of CPC

is concerned with the examination of witnesses by the police.

Section 112(1) provides that the investigating officer (IO) may

examine orally any person acquainted with the facts and

circumstances of the case and shall reduce into writing any

statement made, whereas clause (2) states that the person is bound

to answer all questions asked by IO, except if those statements

would expose him to criminal charge or penalty or forfeiture he may

refuse to answer. Further, section 112(3) requires the person to

state the truth, whether or not such statement is made wholly or

partly in answer to question. Next, the IO must give general caution

under sub(2) and (3). Lastly, the statement shall whenever possible

be taken down in writing and signed by the maker or affixed with his

thumb print after reading it to him in the language he made it and

after giving him an opportunity to correct it.

Pertaining to the situation, ASP Lily has the right to examine Mary

orally regarding the offence alleged. Since the provision mentions

any person, Mary is compelled to produce herself for the purpose

of the investigation and further answer the questions given by ASP

Lily. She is also compelled to state the truth of the matter. The only

exception to this is if the questions asked would likely expose Mary

to criminal charge, penalty or forfeiture. Plus, if Mary happens to

give false information, she may be liable under Section 193 and 203

of the Penal Code.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Go Vs CA, GR No. 101837, February 11,1992Documento4 pagineGo Vs CA, GR No. 101837, February 11,1992AngelNessuna valutazione finora

- Notes On Unlawful Arrest by The PoliceDocumento15 pagineNotes On Unlawful Arrest by The PolicezurainaNessuna valutazione finora

- 16 - Chapter 5 PDFDocumento116 pagine16 - Chapter 5 PDFKrishanParmarNessuna valutazione finora

- School Climate QuestionnaireDocumento1 paginaSchool Climate QuestionnaireAnna-Maria BitereNessuna valutazione finora

- Bresko Habeas Corpus 8-26-11Documento132 pagineBresko Habeas Corpus 8-26-11pbresko100% (1)

- Jenks High School QB ManualDocumento34 pagineJenks High School QB ManualCoach Brown90% (10)

- Examination Under Law of EvidenceDocumento22 pagineExamination Under Law of Evidencechanakyanationallaw100% (1)

- Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia: Subject-Criminal Procedure Code - IDocumento23 pagineFaculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia: Subject-Criminal Procedure Code - IDeepanshu ShakargayeNessuna valutazione finora

- Remand Workshop Papers SummaryDocumento20 pagineRemand Workshop Papers Summarycarl vonNessuna valutazione finora

- How to Hack Wireless Internet ConnectionsDocumento10 pagineHow to Hack Wireless Internet ConnectionsSamibloodNessuna valutazione finora

- Procedure and Ethics (Suggested Answers) - RSEDocumento19 pagineProcedure and Ethics (Suggested Answers) - RSEShy100% (1)

- SEARCH AND SEIZURE - Power PointDocumento51 pagineSEARCH AND SEIZURE - Power PointMitz Zaidonn Francisco100% (1)

- Opposition To Motion To QuashDocumento8 pagineOpposition To Motion To QuashGinn EstNessuna valutazione finora

- Criminal Procedure Code NotesDocumento68 pagineCriminal Procedure Code NotesMudit Gupta100% (2)

- Criminal Procedure Code - CRPC NotesDocumento65 pagineCriminal Procedure Code - CRPC NotesSirajum Munira100% (4)

- German Replacement ArmyDocumento86 pagineGerman Replacement Armyfinriswolf2Nessuna valutazione finora

- Search and seizure rules under Philippine lawDocumento3 pagineSearch and seizure rules under Philippine lawCecilio Chiong Garciano Jr.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lopez vs De Los Reyes: House has power to punish for contemptDocumento6 pagineLopez vs De Los Reyes: House has power to punish for contemptSofia MoniqueNessuna valutazione finora

- CRPC Crash Course LLBDocumento63 pagineCRPC Crash Course LLBRahul parasar100% (1)

- Civil Suit for Specific Performance of Agreement to Sell PropertyDocumento18 pagineCivil Suit for Specific Performance of Agreement to Sell PropertyHimani YadavNessuna valutazione finora

- Given To The Goddess South Indian Devadasi PDFDocumento3 pagineGiven To The Goddess South Indian Devadasi PDFMuslim MarufNessuna valutazione finora

- Yolanda Mercado Vs AMA, DigestDocumento1 paginaYolanda Mercado Vs AMA, DigestAlan Gultia100% (1)

- Ooi Poh EanDocumento22 pagineOoi Poh EanAnita VkNessuna valutazione finora

- Discussion 2 CPCDocumento2 pagineDiscussion 2 CPCAnita Vk100% (1)

- Criminal Procedure On Rights of Arrested PersonDocumento9 pagineCriminal Procedure On Rights of Arrested PersonGrace Lim OverNessuna valutazione finora

- Search and Seizure Criminal Procedural CodeDocumento2 pagineSearch and Seizure Criminal Procedural CodeLina KhalidaNessuna valutazione finora

- Criminal Procedure Quiz 5 ReviewDocumento4 pagineCriminal Procedure Quiz 5 ReviewBalindoa JomNessuna valutazione finora

- Malaysia Legal System 2Documento6 pagineMalaysia Legal System 2MohdIzwanNessuna valutazione finora

- Right to Counsel in Police CustodyDocumento9 pagineRight to Counsel in Police CustodymusheilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Evidence Obtained in Violation of NDPS ActDocumento28 pagineEvidence Obtained in Violation of NDPS ActAnushka PratyushNessuna valutazione finora

- CrPC Search and Seizure PresentationDocumento14 pagineCrPC Search and Seizure PresentationYuvan Sharma100% (1)

- Criminal Law Practice QuestionsDocumento12 pagineCriminal Law Practice QuestionsdunmNessuna valutazione finora

- Stages of A Murder TrialDocumento7 pagineStages of A Murder TrialGautam KrishnaNessuna valutazione finora

- Everything You Need to Know About Criminal Investigation ProceduresDocumento86 pagineEverything You Need to Know About Criminal Investigation ProceduresOJASWANI DIXITNessuna valutazione finora

- LAW OF EVIDENCE Lesson 1-7Documento91 pagineLAW OF EVIDENCE Lesson 1-7Kamugisha JshNessuna valutazione finora

- Tito Douglas Lyimo V. R 1978 L.R.T N.55Documento13 pagineTito Douglas Lyimo V. R 1978 L.R.T N.55Frank marereNessuna valutazione finora

- "Cognizance" As Per Section 190 of CRPCDocumento4 pagine"Cognizance" As Per Section 190 of CRPCAshiNessuna valutazione finora

- Arrest SlidesDocumento96 pagineArrest SlidesTanvi RamdasNessuna valutazione finora

- CRPC Case LawsDocumento16 pagineCRPC Case LawsIshita SethiNessuna valutazione finora

- CRPCDocumento11 pagineCRPCdeekshaNessuna valutazione finora

- Arrest: Sections 41 To 60ADocumento96 pagineArrest: Sections 41 To 60ATanvi RamdasNessuna valutazione finora

- Topic 5 Investigation of CrimesDocumento16 pagineTopic 5 Investigation of Crimesyeo8joanneNessuna valutazione finora

- Tutorial CPCDocumento4 pagineTutorial CPCAkmal Safwan100% (1)

- Illegally Obtained Evidence-Brief NotesDocumento5 pagineIllegally Obtained Evidence-Brief NotesDickson Tk Chuma Jr.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Investigation Process - Role of Courts in Protecting RightsDocumento12 pagineInvestigation Process - Role of Courts in Protecting RightsSyed Rumi AliNessuna valutazione finora

- MsigwaDocumento47 pagineMsigwaPhilbert Bobbyne FerdinandNessuna valutazione finora

- Stop and SearchDocumento6 pagineStop and SearchJabachi NwaoguNessuna valutazione finora

- Name-Aishwarya Monu Semester - Iv ENROLLMENT NO - 20180401008 Subject - Criminal Procedure CodeDocumento10 pagineName-Aishwarya Monu Semester - Iv ENROLLMENT NO - 20180401008 Subject - Criminal Procedure CodeAishwarya MathewNessuna valutazione finora

- Crimpro CDDocumento11 pagineCrimpro CDUrbano, Trinie Anne E.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 3Documento28 pagineUnit 3dineshNessuna valutazione finora

- Assignment CPCDocumento5 pagineAssignment CPCadibah nabilahNessuna valutazione finora

- 2B 2019133218Documento3 pagine2B 2019133218Benilde DungoNessuna valutazione finora

- Advanced Criminal Procedure I - Assignment IDocumento12 pagineAdvanced Criminal Procedure I - Assignment IKhairul IdzwanNessuna valutazione finora

- InvestigationDocumento18 pagineInvestigationSw sneha 18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Preliminary Investigation EssentialsDocumento28 paginePreliminary Investigation EssentialsNHASSER PASANDALANNessuna valutazione finora

- Police powers to break doors for liberationDocumento2 paginePolice powers to break doors for liberationmahnoor tariqNessuna valutazione finora

- Retracted Confessions and the Afsal Guru CaseDocumento11 pagineRetracted Confessions and the Afsal Guru CaseVishesh TyagiNessuna valutazione finora

- CRPCDocumento16 pagineCRPCSw sneha 18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Who May AppealDocumento31 pagineWho May AppealHeren meNessuna valutazione finora

- Remand Power of MagistrateDocumento8 pagineRemand Power of MagistratePratap C.E0% (1)

- Preliminary Investigation Requirements and ProceduresDocumento16 paginePreliminary Investigation Requirements and ProceduresAJDV AJDVNessuna valutazione finora

- Criminal Procedure Code - SearchDocumento2 pagineCriminal Procedure Code - Searchebby1985100% (1)

- Warrant Trail ProcedureDocumento2 pagineWarrant Trail Procedurerrahuldeshpande9Nessuna valutazione finora

- Right of The Arrested PersonDocumento3 pagineRight of The Arrested PersonMush EsaNessuna valutazione finora

- Dr. Devendra Kumar Arora and Dr. Vijay Lakshmi, JJ.: Equivalent Citation: 2017 (5) ALJ 71Documento5 pagineDr. Devendra Kumar Arora and Dr. Vijay Lakshmi, JJ.: Equivalent Citation: 2017 (5) ALJ 71Ankit parasharNessuna valutazione finora

- General Principles of Fair Trial CH Vivek AnandDocumento13 pagineGeneral Principles of Fair Trial CH Vivek AnandsarayusindhuNessuna valutazione finora

- Evidence ProjectDocumento26 pagineEvidence ProjectSiddharthSharma100% (2)

- Answer Sheet: Shaheed Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto University of Law, KarachiDocumento10 pagineAnswer Sheet: Shaheed Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto University of Law, KarachiMuhammad Daud KalhoroNessuna valutazione finora

- Answers of CRPC PYQsDocumento15 pagineAnswers of CRPC PYQsVivek VibhushanNessuna valutazione finora

- Evidence Summarrised Notes Moi CampusDocumento83 pagineEvidence Summarrised Notes Moi Campusjohn7tago100% (1)

- EcofirstDocumento23 pagineEcofirstAnita VkNessuna valutazione finora

- Appadurai A/l Ponnusamy v. Pentadbir Harta Pesaka Appalasamy A/l Nookiah, Deceased & AnorDocumento12 pagineAppadurai A/l Ponnusamy v. Pentadbir Harta Pesaka Appalasamy A/l Nookiah, Deceased & AnorAnita VkNessuna valutazione finora

- CLJ 2018 9 449 Puukm1Documento35 pagineCLJ 2018 9 449 Puukm1Anita VkNessuna valutazione finora

- CLJ 2018 3 635 ChrislailawDocumento20 pagineCLJ 2018 3 635 ChrislailawAnita VkNessuna valutazione finora

- CLJ 2010 5 83 ChrislailawDocumento26 pagineCLJ 2010 5 83 ChrislailawAnita VkNessuna valutazione finora

- Oral agreements to secure projects for commissions found illegalDocumento22 pagineOral agreements to secure projects for commissions found illegalAnita VkNessuna valutazione finora

- CLJ 2021 7 755 ChrislailawDocumento39 pagineCLJ 2021 7 755 ChrislailawAnita VkNessuna valutazione finora

- Requirements for pleadings in court casesDocumento1 paginaRequirements for pleadings in court casesAnita Vk100% (1)

- The Future of Digital Lockers : (2015) 1 LNS (A) Lxvi Legal Network Series 1Documento11 pagineThe Future of Digital Lockers : (2015) 1 LNS (A) Lxvi Legal Network Series 1Anita VkNessuna valutazione finora

- Authorization Letter for DisputeDocumento2 pagineAuthorization Letter for DisputeAnita VkNessuna valutazione finora

- Personal Injury Quantum Tables: Abdomen Liver by Award High To Low Abdomen#Liver#H2L#2007 - 2009Documento1 paginaPersonal Injury Quantum Tables: Abdomen Liver by Award High To Low Abdomen#Liver#H2L#2007 - 2009Anita VkNessuna valutazione finora

- Contract of RetainerDocumento1 paginaContract of RetainerAnita VkNessuna valutazione finora

- Kumpulan Tutorialsenarai Kumpulan Tutorial Uuuk4033 Sesi 1 2016 2017Documento4 pagineKumpulan Tutorialsenarai Kumpulan Tutorial Uuuk4033 Sesi 1 2016 2017Anita VkNessuna valutazione finora

- CLJ 2010 6 24 Puukm1Documento10 pagineCLJ 2010 6 24 Puukm1Anita VkNessuna valutazione finora

- 12 JSSH Vol 23 (S) Oct 2015 - pg153-168Documento16 pagine12 JSSH Vol 23 (S) Oct 2015 - pg153-168Anita VkNessuna valutazione finora

- Hearsay in Malaysia The Case For RekkformDocumento8 pagineHearsay in Malaysia The Case For RekkformAnita VkNessuna valutazione finora

- Ryn Present Cyber LawDocumento30 pagineRyn Present Cyber LawAnita VkNessuna valutazione finora

- Case - (1938) 1 LNS 32Documento4 pagineCase - (1938) 1 LNS 32Anita VkNessuna valutazione finora

- Ap41s 81 2009Documento11 pagineAp41s 81 2009Anita VkNessuna valutazione finora

- Appellant's SubmissionDocumento2 pagineAppellant's SubmissionAnita VkNessuna valutazione finora

- Case - (1938) 1 LNS 32Documento4 pagineCase - (1938) 1 LNS 32Anita VkNessuna valutazione finora

- CLJ 2010 6 24 Puukm1Documento10 pagineCLJ 2010 6 24 Puukm1Anita VkNessuna valutazione finora

- The Indian Tolls (Army and Air Force) Act, 1901-15 Sep2004Documento7 pagineThe Indian Tolls (Army and Air Force) Act, 1901-15 Sep2004Prr RaoNessuna valutazione finora

- 144,000 Foundation.Documento4 pagine144,000 Foundation.Kerjiokchuol bothNessuna valutazione finora

- ObliconDocumento12 pagineObliconagent_rosNessuna valutazione finora

- Preview of " ATF To Spy On Gun Owners Via "Massive" Database Alex Jones' Infowars - There's A War On For Your Mind!"Documento15 paginePreview of " ATF To Spy On Gun Owners Via "Massive" Database Alex Jones' Infowars - There's A War On For Your Mind!"winterrossNessuna valutazione finora

- HRW Japan0720 - WebDocumento73 pagineHRW Japan0720 - WebsofiabloemNessuna valutazione finora

- Wembley Stadium ScheduleDocumento1 paginaWembley Stadium SchedulewembleystadiumeventsNessuna valutazione finora

- Native AmericaDocumento6 pagineNative AmericaAí NguyễnNessuna valutazione finora

- Buenaventura V Ca PDFDocumento19 pagineBuenaventura V Ca PDFbrida athenaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Sniper by Liam ODocumento2 pagineThe Sniper by Liam OWasif ZaNessuna valutazione finora

- Prudential Bank Vs NLRCDocumento2 paginePrudential Bank Vs NLRCErika Mariz CunananNessuna valutazione finora

- TalesoftheOtherSide FinalwebDocumento90 pagineTalesoftheOtherSide FinalwebKo ZanNessuna valutazione finora

- Philippine National Oil Company vs. Court of AppealsDocumento121 paginePhilippine National Oil Company vs. Court of AppealsMark NoelNessuna valutazione finora

- Yogesh Dr. ListDocumento1 paginaYogesh Dr. ListJeremymartinsNessuna valutazione finora

- A.C. No. 5305 March 17, 2003 Marciano P. Brion, JR., Petitioner, FRANCISCO F. BRILLANTES, JR., Respondent. Quisumbing, J.Documento10 pagineA.C. No. 5305 March 17, 2003 Marciano P. Brion, JR., Petitioner, FRANCISCO F. BRILLANTES, JR., Respondent. Quisumbing, J.KP Gonzales CabauatanNessuna valutazione finora

- Money Receipt: Kogta Financial (India) LimitedDocumento2 pagineMoney Receipt: Kogta Financial (India) LimitedMARKOV BOSSNessuna valutazione finora

- Stok Tanggal 10 November 2023Documento3 pagineStok Tanggal 10 November 2023Nita FitriNessuna valutazione finora

- General Conference Fishing GameDocumento2 pagineGeneral Conference Fishing Gameamleef100% (5)

- Comparing Common Law and Civil Law TraditionsDocumento10 pagineComparing Common Law and Civil Law TraditionsMuhammad FaizanNessuna valutazione finora

- Questions and Notes On LandDocumento15 pagineQuestions and Notes On LandReal TrekstarNessuna valutazione finora

- Philippine Organic Act of 1902Documento44 paginePhilippine Organic Act of 1902rixzylicoqui.salcedoNessuna valutazione finora

- 4 1 23 McLaughlin DJTFP24 Polling MemoDocumento3 pagine4 1 23 McLaughlin DJTFP24 Polling MemoBreitbart NewsNessuna valutazione finora