Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

1901 St. Louis First Modern Medical Disaster

Caricato da

namename99999Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

1901 St. Louis First Modern Medical Disaster

Caricato da

namename99999Copyright:

Formati disponibili

The 1901 St Louis Incident: The First Modern Medical Disaster

Ross E. DeHovitz

Pediatrics 2014;133;964; originally published online May 26, 2014;

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2013-2817

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

located on the World Wide Web at:

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/133/6/964.full.html

PEDIATRICS is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

publication, it has been published continuously since 1948. PEDIATRICS is owned,

published, and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point

Boulevard, Elk Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright 2014 by the American Academy

of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0031-4005. Online ISSN: 1098-4275.

Downloaded from pediatrics.aappublications.org at HAM-TMC Library on June 17, 2014

a,b

AUTHOR: Ross E. DeHovitz, MD

a

Palo Alto Medical Foundation, Palo Alto, California; and bDepartment of

Pediatrics, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California

Address correspondence to Ross E. DeHovitz, MD, Palo Alto Medical Foundation,

795 El Camino Real, Palo Alto, CA 94301. E-mail: dehovir@pamf.org

Accepted for publication Nov 6, 2013

KEY WORDS

antitoxin, diphtheria, tetanus

doi:10.1542/peds.2013-2817

The 1901 St Louis Incident: The First Modern

Medical Disaster

On October 19, 1901, Dr R.C. Harris, a

St Louis physician, attended to a young

girl named Bessie Baker who was suffering from advanced diphtheria. As was

his routine, he injected diphtheria antitoxin into the child and, as a preventive,

her 2 younger siblings and concluded that

she would soon be entirely well. But 4

days later he was called back to the

Bakers home to a terrifying discovery:

There I found that the little girl was

suffering from tetanus (lockjaw). I could

do nothing for her. The poison was

injected so thoroughly into her system

that she was beyond medical aid.1

Bessie died of tetanus the following

day, as did her 2 siblings within the

week. So began one of the worst safety

disasters in the history of American

public health, in which, by the time it

was over, some 13 children had died of

tetanus from contaminated antisera.

Diphtheria was a scourge throughout

the 19th century. It primarily affected

children, and it killed through the release of an exotoxin that creates

a pseudomembrane inside the throat of

affected patients. When death occurred,

which it did in 10% to 40% of patients, it

did so primarily through asphyxiation.

In 1884, Friedrich Loefer, a scientist in

Berlin, discovered how to culture diphtheria in the laboratory and he grew it

in guinea pigs. Loefers colleagues in

964

Germany and Paris developed experiments proving that a diphtheria toxin

when injected into guinea pigs, and

later dogs and horses, produced a substance in their blood that could be used

to treat diphtheria in another species.2

In September 1894, Emile Roux in Paris

announced that his horse antiserum

had cut diphtheria mortality from 56%

to 24% in his Paris hospital. There was

great interest in bringing this new

treatment to America. Consequently,

the rst horse antitoxin factory was

established in New York and produced

its rst doses in January 1895 (Supplemental Figure 1).2

The Health Commission in St Louis,

Missouri, decided to bring this technology to the people of their city as

well. They established a factory/farm

in late 1894, with the rst doses becoming available in September 1895.

Amand Ravold, a local physician and

trained bacteriologist, was hired by

the city to direct this project.

Dr Ravold studied in Paris as a pupil of

Louis Pasteur in the developing science of bacteriology. Antitoxin was

becoming available to the city from

private rms, but the health commissioner wanted the city to establish its

own supply of antitoxin to be able to

offer it free to the poor.

By 1901, 6 years after its introduction in

the St Louis area, the use of antitoxin for

the treatment of diphtheria had become

very successful. It became the standard

treatment of presumptive pharyngeal

diphtheria. It was in this environment that

the seeds of a tragedy began to take form.

On September 30, 1901, Dr Ravold bled

a horse named Jim and acquired 2

asks of serum. Jim had been an

ambulance horse, and he was turned

over to the stables in 1898 for antitoxin

production (Supplemental Figure 5).

On October 2nd, Jim became ill with

tetanus and was killed. The antiserum

obtained on September 30th was ordered to be destroyed.

On October 26, 1901, the health department was notied by a physician

that he had under observation 2 cases

of tetanus after the use of diphtheria

antiserum. Veronica ONeill Keenan was

the rst case reported. Bessie and May

Baker died shortly thereafter. Jacob

Senturia, like the others, had initially

responded to the diphtheria antiserum, but then 6 days later his physician found the patient suffering

from trismus sardonicus: There was

a rigid spine, rigid neck and the patient rested on his occiput and heels

and he was cyanotic.3 Jacob died on

October 30th.

DEHOVITZ

Downloaded from pediatrics.aappublications.org at HAM-TMC Library on June 17, 2014

MONTHLY FEATURE

Over the next few days, as more children died, the health department

recalled the existing bottles of antitoxin and began an investigation. By

November 7th, the 13th death had

been reported (Supplemental Figures 2

and 4).

The incident was reported nationwide,

and the public became fearful. In

Chicago, the diphtheria case fatality

rate increased by one-third. In the

Journal of the American Medical Association, an editorial was published

with the title Unjustiable Distrust of

Diphtheria Antitoxin. The editorial

warned of signicantly more deaths

unless physicians demand [from the

manufacturers] a guaranteed purity

of antitoxin and are thus enabled to

speak with the condence of denite

knowledge and so inspire the anxious

parent with their own condence.4

Back in St Louis, the Tetanus Court of

Inquiry began on December 17th. Dr

Ravold had insisted that he and Henry

Taylor, the colored janitor as the

newspapers referred to him, had disposed of the September 30th serum

after the horse died. But Taylors story

began to change after he was closeted with the Chief of Detectives by

order of Mayor Wells.5 After this prolonged interrogation, Taylor was

promptly placed back on the stand

where he stated that he did release

some of the serum dated September

30th (Supplemental Figure 3). He released it, he stated, because he

thought it was safe and because the

August 24th serum was exhausted.5

On February 13, 1902, the commission

issued their verdict stating that the 13

children died of tetanus-contaminated

vials dated September 30th. Second,

the commission found that Henry

Taylor, the janitor, bottled the serum

but was not fully aware of its poisonous nature. Conversely, Dr Ravold

was aware of the dangerous nature of

the September 30th serum but was

negligent in ensuring that it was

destroyed. Last, both Dr Ravold and

Taylor were to be dismissed from the

Health Department (Supplemental

Figure 6).5

Dr Ravold responded to the verdict

stating that the Board had wrongly

dismissed Taylor: Taylor, a man of 65,

honest and faithful, was not supposed

to be competent to look after the professional affairs of the ofce. He was

simply a good servant and this discharge will leave him in hard times.5

After the incident, the city ceased all

antitoxin production. Yet, it was largely

because of the St Louis incident, and

a similar incident in Camden, New

Jersey, where there were 9 deaths,

that Congress would pass the Biologics

Control Act in the spring of 1902.

Among the arguments made was

a statement that individual states were

powerless to protect themselves

against impure and impotent materials6 because most of them consumed biologics made out of state.

The act took effect on July 1, 1902, and

subjected any company making antitoxin or vaccines to inspections and

regulations. Many companies went out

of business under this increased

scrutiny. But the result of this legislation, and legislation a few years

later that created the Food and Drug

Administration, was to increase the

safety and public condence in these

lifesaving new therapies.6

There would be other medical disasters over the course of the 20th

century. But this 1901 incident was

arguably the rst ever using a modern medical therapy. Antitoxin, now

cleared from suspicion, continued to

drive down the death rate of this

terrifying disease until a vaccine using a formalin-inactivated toxin or

toxoid became available in 1922.7

Dr Ravold went on to have a distinguished career as a bacteriologist, and

he was elected president of the St

Louis Medical Society. When he died at

age 83 in 1942, his obituary made no

mention of the diphtheria antitoxin

incident of 1901.

After Henry Taylor was red from the

St Louis Health Department, he found

work as a waiter and caterer. He died

on June 6, 1907, from chronic nephritis

and cancer. The physician who signed

his death certicate was Dr Ravold.

REFERENCES

1. Interview with Dr. R. C. Harris. St Louis Post

Dispatch. October 30, 1901: 1

2. Allen A. Vaccine, the Controversial Story of

the Worlds Greatest Lifesaver. New York, NY:

W.W. Norton and Company; 2007:123124

3. Golland M. Report of coroners inquest, Jacob

Senturia, October 30, 1901

4. Unjustiable distrust of diphtheria antitoxin.

J Am Med Assoc. 1901;37:13961397

5. St Louis Republic. December 27, 1901, February 13, 1902

6. Willrich M. Pox: An American History. New

York, NY: Penguin Press; 2011:200

7. Colgrove J. State of Immunity. Berkeley, CA:

University of California Press; 2006:109112

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The author has indicated he has no nancial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: No external funding.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The author has indicated he has no potential conicts of interest to disclose.

PEDIATRICS Volume 133, Number 6, June 2014

Downloaded from pediatrics.aappublications.org at HAM-TMC Library on June 17, 2014

965

The 1901 St Louis Incident: The First Modern Medical Disaster

Ross E. DeHovitz

Pediatrics 2014;133;964; originally published online May 26, 2014;

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2013-2817

Updated Information &

Services

including high resolution figures, can be found at:

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/133/6/964.full.ht

ml

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material can be found at:

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/suppl/2014/05/2

0/peds.2013-2817.DCSupplemental.html

Permissions & Licensing

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures,

tables) or in its entirety can be found online at:

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xh

tml

Reprints

Information about ordering reprints can be found online:

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

PEDIATRICS is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly

publication, it has been published continuously since 1948. PEDIATRICS is owned, published,

and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point Boulevard, Elk

Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright 2014 by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All

rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0031-4005. Online ISSN: 1098-4275.

Downloaded from pediatrics.aappublications.org at HAM-TMC Library on June 17, 2014

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Da Silva - On Matter Beyond The Equation of ValueDocumento11 pagineDa Silva - On Matter Beyond The Equation of Valuenamename99999Nessuna valutazione finora

- 0 McKittrick - Dear ScienceDocumento198 pagine0 McKittrick - Dear Sciencenamename99999Nessuna valutazione finora

- 0 James Concerning Violence Fanon Black CyborgDocumento15 pagine0 James Concerning Violence Fanon Black Cyborgnamename99999Nessuna valutazione finora

- Flowers On Mt. Tam by Bola SeteDocumento5 pagineFlowers On Mt. Tam by Bola Setenamename99999Nessuna valutazione finora

- Stark - On Esposito - Network of ObserversDocumento11 pagineStark - On Esposito - Network of Observersnamename99999Nessuna valutazione finora

- OnlineHebrewTutorialEnglish PDF LNK PDFDocumento36 pagineOnlineHebrewTutorialEnglish PDF LNK PDFnamename99999Nessuna valutazione finora

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Smith CV IptecDocumento6 pagineSmith CV Iptecapi-447191360Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan ScenarioDocumento2 pagineLesson Plan Scenarioapi-247663890Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cost Break Down For Kaluthra Kalu, Mahrgama Nine Puppies and DeltaDocumento10 pagineCost Break Down For Kaluthra Kalu, Mahrgama Nine Puppies and DeltaAdopt a Dog in Sri LankaNessuna valutazione finora

- Microbiology Last Moment RevisionDocumento16 pagineMicrobiology Last Moment RevisionDeepak MainiNessuna valutazione finora

- 3 HIV Vidas Duo UltraDocumento7 pagine3 HIV Vidas Duo UltraAndri HaryonoNessuna valutazione finora

- Coagulase TestDocumento3 pagineCoagulase TestVanandiNessuna valutazione finora

- EYE Emergency Manual An Illustrated Guide: Second EditionDocumento56 pagineEYE Emergency Manual An Illustrated Guide: Second Editionmanleyj5305Nessuna valutazione finora

- DIAGNOSTICS (Student Copy)Documento59 pagineDIAGNOSTICS (Student Copy)Abigail Mayled LausNessuna valutazione finora

- BDDocumento10 pagineBDtorajasaNessuna valutazione finora

- Non-Priority: This Is Not A Boarding CardDocumento2 pagineNon-Priority: This Is Not A Boarding CardHa My PhamNessuna valutazione finora

- Daily Shouko #543Documento15 pagineDaily Shouko #543Joshua TercenoNessuna valutazione finora

- RockerDocumento2 pagineRockerwan hseNessuna valutazione finora

- FCM National-Rabies-Control-ProgramDocumento15 pagineFCM National-Rabies-Control-ProgramMaikka IlaganNessuna valutazione finora

- NICU Standing Orders KFAFHDocumento36 pagineNICU Standing Orders KFAFHallysonviernes100% (1)

- ENT Deferential Diagnosis MEDADDocumento22 pagineENT Deferential Diagnosis MEDADReham AshourNessuna valutazione finora

- Pharma QuestionsDocumento5 paginePharma QuestionsLey BeltranNessuna valutazione finora

- Biliary AtresiaDocumento9 pagineBiliary AtresiaPrabhakar KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Communicable Disease: List of Communicable DiseasesDocumento13 pagineCommunicable Disease: List of Communicable DiseasesjasmineNessuna valutazione finora

- Generic Name: Quinupristin/Dalfopristin - Injection (Kwin-ue-PRIS-tin/DAL-foe-PRIS-tin)Documento4 pagineGeneric Name: Quinupristin/Dalfopristin - Injection (Kwin-ue-PRIS-tin/DAL-foe-PRIS-tin)Jrose CuerpoNessuna valutazione finora

- Cap Guidelines 2010Documento42 pagineCap Guidelines 2010Marion Andrea PoblacionNessuna valutazione finora

- Who Guidelines Blood Donor Selection 2012Documento126 pagineWho Guidelines Blood Donor Selection 2012Dananjaya Junior100% (1)

- Catalogue Lsi 2010 UKDocumento72 pagineCatalogue Lsi 2010 UKNesak1980Nessuna valutazione finora

- Concepts Theory EpidemiologyDocumento48 pagineConcepts Theory EpidemiologyStephanie Wong100% (1)

- Infection Control Risk Assessment Tool 1208Documento7 pagineInfection Control Risk Assessment Tool 1208Ama AhyarNessuna valutazione finora

- The Microbiology of Wounds: Neal R. Chamberlain, PH.D., Department of Microbiology/Immunology KcomDocumento31 pagineThe Microbiology of Wounds: Neal R. Chamberlain, PH.D., Department of Microbiology/Immunology KcomFhaliesha Zakur100% (1)

- Australia Visa PDFDocumento6 pagineAustralia Visa PDFminjiew50% (2)

- Self-Amplifying RNA Vaccines For Infectious DiseasesDocumento13 pagineSelf-Amplifying RNA Vaccines For Infectious DiseasesRicardo SousaNessuna valutazione finora

- Babesia MicrotiDocumento9 pagineBabesia MicrotiFrancene Ac-DaNessuna valutazione finora

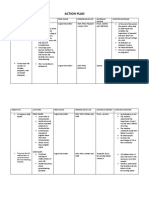

- Action PlanDocumento4 pagineAction PlanJosette Mae Atanacio67% (3)