Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Omeprazole-Mg 20.6 MG Is Superior To Lansoprazole 15 MG For Control of Gastric Acid: A Comparison of Over-The-Counter Doses of Proton Pump Inhibitors

Caricato da

rahmaDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Omeprazole-Mg 20.6 MG Is Superior To Lansoprazole 15 MG For Control of Gastric Acid: A Comparison of Over-The-Counter Doses of Proton Pump Inhibitors

Caricato da

rahmaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics

Omeprazole-Mg 20.6 mg is superior to lansoprazole 15 mg for

control of gastric acid: a comparison of over-the-counter doses

of proton pump inhibitors

P. B. MINER JR*, L. A. MCKEAN, R. D . GIBB, G. N. E RASALA, D. L. RAMSEY & J. W. MCRORIE

*Oklahoma Foundation for Digestive

Research, Oklahoma City, OK, USA;

The Procter & Gamble Company,

Cincinnati, OH, USA

Correspondence to:

Dr J. W. McRorie, The Procter &

Gamble Company, 8700 Mason

Montgomery Road, Mason, OH 45040,

USA.

E-mail: mcrorie.jw@pg.com

Publication data

Submitted 25 January 2010

First decision 29 January 2010

Resubmitted 4 February 2010

Accepted 5 February 2010

Epub Accepted Article 8 February

2010

SUMMARY

Background

Over-the-counter (OTC) proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) relieve heartburn

by decreasing the production of gastric acid, but may not do so with

equal effectiveness. It is important for healthcare professionals to compare the ability of OTC PPIs to control gastric acid when recommending

them for patients with frequent heartburn.

Aim

To compare the effects of omeprazole-Mg 20.6 mg and lansoprazole

15 mg (OTC doses in the US) on 24-h steady state gastric acid suppression.

Methods

This single-centre, randomized, double-blind clinical study compared

the steady-state gastric acid control of omeprazole-Mg 20.6 mg vs. lansoprazole 15 mg, dosed before breakfast. Volunteers were enrolled in a

3-period, cross-over design (ABB, BAA) with 24-h gastric pH monitoring on dosing day 5. The primary efficacy variable was the percentage

time intragastric pH was >4.0 over 24 h on day 5 of dosing.

Results

Forty subjects were enrolled; all completed the study. The mean (SE)

percentage time pH was >4.0 was 45.7% (3.45%) for omeprazole-Mg

20.6 mg and 36.8% (3.45%) for lansoprazole 15 mg, an absolute difference of 8.9% (P < 0.0001), and a relative difference of 24.2%. Both

drugs were well tolerated.

Conclusion

Omeprazole-Mg 20.6 mg provided a statistically significantly

(P < 0.0001) greater acid control than lansoprazole 15 mg.

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 31, 846851

846

2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04258.x

O T C O M E P R A Z O L E V S . L A N S O P R A Z O L E I N A C I D C O N T R O L 847

INTRODUCTION

Frequent heartburn is widely treated with acid suppression therapies.1 Consumer surveys show that a significant proportion of consumers with frequent

heartburn are dissatisfied with their current OTC products.2 It is commonly assumed that histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) are superior to proton pump

inhibitors (PPIs) for acid suppression over the first day

of therapy, but a recent head-to-head clinical study

demonstrated that this assumption is inaccurate.3 That

three-treatment, 3-period cross-over study compared

gastric acid suppression efficacy of a PPI, omeprazoleMg 20.6 mg, dosed once daily, vs. an H2RA, famotidine, dosed as 10 mg twice daily and 20 mg twice

daily, for 14 days. The study demonstrated that omeprazole-Mg 20.6 mg provided gastric acid suppression

that was superior to famotidine 10 mg (P = 0.032),

comparable to famotidine 20 mg on the first day of

dosing, and superior to both famotidine doses thereafter over the 14-day dosing period.

Dosed before meal times, PPIs are the most effective

acid inhibitors currently available, and the most

widely prescribed class of gastrointestinal medications.4 Most pharmacodynamic studies assessing gastric acid control have evaluated high-dose prescription

strength PPIs. With the emergence of OTC PPIs, it is

important for healthcare professionals to understand

the relative ability of the available OTC doses to control gastric acid when making recommendations to

patients. This study represents one of the largest crossover studies to date to compare the relative gastric

acid control of omeprazole-Mg 20.6 mg and lansoprazole 15 mg (the OTC doses in the US).

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Subjects

Male and female subjects were considered eligible for

enrolment if they were between 18 and 65 years of age

and generally healthy with no unstable medical conditions; had a Body Mass Index (BMI) less than 32; were

Helicobacter pylori-negative; and, if women, were postmenopausal or were using an acceptable method of

contraception. Subjects were excluded from the study if

they were pregnant or nursing; had a significant medical or mental illness that would contraindicate participation in the study; had current significant

gastrointestinal disease or a history of gastrointestinal

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 31, 846851

2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

disease other than frequent heartburn. During the

study, subjects were instructed not to use medications

that could affect gastric pH or gastrointestinal motility.

Study design

This single-centre, double-blind, randomized, twotreatment, 3-period cross-over study was conducted by

the Oklahoma Foundation for Digestive Research in

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma between April and June,

2009. During each dosing period, each subject received

1 of 2 study treatments daily: omeprazole-Mg 20.6 mg

tablet (Prilosec OTC, Astra Zeneca, Lund, Sweden) or

lansoprazole 15 mg capsule (Prevacid, Takeda Pharmaceuticals America, Deerfield, IL, USA). Although the

prescription product was used in this study, this product is the same formulation now available OTC as

Prevacid24 Hr. Subjects were randomized to one of

two treatment sequences (ABB, BAA), so that the treatment subjects received during the second period was

repeated during the third period. A randomization

schedule was generated by the sponsor using a series

of computer-generated random numbers and provided

to the investigator. This 3-period design provides for a

more robust statistical analysis of the data than is possible with the standard 2-period AB BA design. More

specifically, if carryover is detected in the AB BA

design, it is impossible to both model the carryover

effect and perform a within-subject test for treatment.

Consequently, one must discard the data from period 2

and analyse the period 1 data as a parallel-groups

design. In contrast, our 3-period design provides for a

within-subject test for treatment even if carryover is

detected. The 3-period design also has a greater statistical power to differentiate treatment for the same

number of subjects.5 Study treatment was taken under

study site supervision for five consecutive days during

each dosing period. On days 1 through 4, subjects

reported to the site for dosing, followed by breakfast

and then were dismissed for the rest of the day. Subjects reported to the study facility on the evening prior

to day 5 of each treatment period for an overnight

stay and then remained at the site throughout the 24-h

period of gastric pH monitoring on day 5. Day 5 was

considered an appropriate time point for measurement

of gastric pH because the onset of acid inhibition with

PPIs is generally considered to be at steady-state by

that time.6, 7 There was a 10-day washout period

between treatment period. The subjects, investigator,

and study personnel were blinded to the treatment.

848 P . B . M I N E R J R et al.

The treatment blind was maintained by having all

study doses provided to subjects at the time of dosing

in an opaque envelope by a pharmacist who had no

other involvement with the study.

After reporting to the site on the evening prior to

day 5, subjects were not allowed to consume food or

drink after midnight. On day 5, subjects were awakened at approximately 5 AM for placement of the calibrated pH probe, which was connected to a pH data

acquisition device (ZepHr pH monitor with ComforTEC

disposable catheters, Sandhill Scientific, Highlands

Ranch, CO, USA). Confirmation of the gastric location

of the digital electrode was determined by a direct

reading of an acidic pH from the pH monitor. The

monitor was put in standby mode until approximately

7:00 AM when the pH data collection began. The pH

measurements were recorded every 5 s for 24 h.

Immediately after beginning the pH recordings, subjects received their assigned treatment according to

the study randomization sequence for the period followed by a standardized breakfast meal. Standard

meals were also supplied for lunch (12:30 PM) and dinner (6:00 PM). At the end of the 24-h gastric pH data

collection, the catheters were removed and the subjects

were allowed to leave with a reminder to return at

their next scheduled appointment. The process was

repeated for periods 2 and 3.

This study was approved by the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center Institutional Review

Board and conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) Harmonized

Tripartite Guideline for Good Clinical Practice and the

ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to undergoing any study-related

procedure, subjects provided written informed consent.

Subjects were queried about any adverse events during

each study visit and all adverse events, whether solicited or volunteered, were recorded. This clinical trial

was registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov (Registration number: NCT 00903448).

Statistical methods

The primary efficacy variable was the percentage time

that gastric pH was greater than 4.0 during 24-h monitoring on day 5 of dosing. The percentage time that

gastric pH is greater than four is a parameter that has

been used frequently to predict the clinical efficacy of

gastric acid-suppression therapies.3, 6 The secondary

efficacy endpoint was the percentage time that gastric

pH was greater than 4.0 during the period from

10:00 PM to 6:00 AM. Only subjects who had at least 1

period of pH data for each treatment were included in

the efficacy analysis. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) for

cross-over designs was carried out separately on the

primary and secondary endpoints data using the

Mixed procedure of SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute,

Cary, NC, USA). The statistical model included treatment, period, and carryover as fixed effects and subject as a random effect. The significance of Carryover

was determined for the model and was found to be

statistically insignificant (primary, P = 0.99; secondary, P = 0.22). As per the protocol, a reduced model

without Carryover was used to compare treatments.

Both the mean absolute difference (omeprazole-Mg

lansoprazole) and the mean relative percentage difference [100% (omeprazole-Mg lansoprazole)

lansoprazole] between treatments were calculated from

the treatment means. Hypotheses were tested at a significance level of 5%.

The following post hoc analyses were also performed. ANOVA was used to compare treatments with

respect to the following 24-h endpoints: percentage

time pH was greater than 2.0, percentage time pH was

greater than 3.0, percentage time pH was greater than

5.0, and median gastric pH. A histogram of the

within-subject treatment ratio (omeprazole-Mg divided

by lansoprazole) of the percentage time pH was greater

than 4.0 was prepared.

Forty subjects were planned for enrolment to ensure

that at least 30 subjects would have complete data for

all three treatment periods. It was estimated that this

sample size would provide at least 80% power to detect

an absolute treatment difference of 6.5%, e.g. 50% vs.

43.5%, in two-sided testing at the 5% significance level.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics and subject

disposition

The subjects were generally young and predominantly

male and Caucasian (Table 1). Forty subjects were randomized to treatment sequence. All subjects completed

the study with at least 1 period of pH data for each

treatment. Data in Period 3 for 2 subjects were incomplete because of equipment failure and were excluded

from the analysis. As a result, the analysis included

data from all 40 subjects and 118 of a potential 120

dosing periods (98.3%).

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 31, 846851

2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

O T C O M E P R A Z O L E V S . L A N S O P R A Z O L E I N A C I D C O N T R O L 849

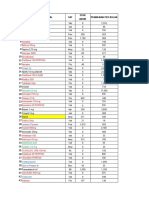

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of subjects (n = 40)

Age (years)

Mean (s.d.)

Range

Gender

Female

Male

Race

Caucasian

Hispanic

Black

28

20

n

12

28

n

37

2

1

(6.65)

to 51

(%)

(30)

(70)

(%)

(93)

(5)

(3)

Efficacy

The mean percentage time that gastric pH was greater

than 4.0 over 24 h during day 5 of dosing was highly

significantly greater for omeprazole-Mg 20.6 mg

(mean, 45.7%; S.E., 3.45%) than for lansoprazole

15 mg (mean, 36.8%; S.E., 3.45%) (P < 0.0001). The

absolute mean difference between treatments was

8.9% (S.E., 2.10%) and the mean relative percentage

difference was 24.2%. The mean (S.E.) percentage time

that gastric pH was greater than 4.0 from 10 PM to

6 AM was 24.3% (3.91%) with omeprazole-Mg 20.6 mg

and 21.8% (3.91%) with lansoprazole 15 mg

(P = 0.28). When median pH values were plotted over

time, a clear majority of post-prandial median pH values were higher with omeprazole-Mg 20.6 mg than

with lansoprazole 15 mg (Figure 1).

Subjects receiving omeprazole-Mg experienced more

time above any given gastric acid pH value than subjects receiving lansoprazole across the range of pH

values (Figure 2). The difference between treatments

was highly statistically significant (P 0.0023) regardless of the pH value chosen (Table 2).

The mean median (S.E.) gastric pH was 3.685 (0.20)

with omeprazole-Mg and 3.058 (0.20) with lansoprazole (P < 0.0001).

The distribution of within-subject omeprazole-tolansoprazole ratios for the percentage time that gastric

pH was greater than 4.0 is shown Figure 3. For 29 of

40 (72.5%) subjects, the percentage time pH was

greater than 4.0 was larger with omeprazole-Mg than

with lansoprazole.

Safety

There were no serious adverse events in the study. No

adverse event required treatment or caused the subject

to discontinue treatment.

Figure 2. Mean percentage

time that gastric pH was

greater than a given value by

treatment. Data are for 40 subjects, 118 24-h pH recordings.

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 31, 846851

2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

4

3

2

1

Lansoprazole 15 mg

Omeprazole-Mg 20.6 mg

0

7 am

10 am

1 pm

4 pm

7 pm

10 pm

1 am

4 am

7 am

Time

Mean % time pH > pH level

Figure 1. Median gastric pH at

each time point (every 5 s)

over the 24-h treatment period. Mealtimes were 7 AM,

12:30 PM and 6:00 PM. Data

are for 40 subjects, 118 24-h

pH recordings.

Median gastric pH

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Lansoprazole 15 mg

Omeprazole-Mg 20.6 mg

4

pH level

850 P . B . M I N E R J R et al.

Table 2. Percentage time that gastric pH was greater than specified pH threshold. Data are for 40 subjects, 118 24-h pH

recordings

Mean (S.E.)*

pH

threshold

Omeprazole-Mg

20.6 mg

Lansoprazole

15 mg

Difference

mean (S.E.)*

P-value*

Relative percentage

difference

>2.0

>3.0

>4.0

>5.0

72.6

58.5

45.7

30.9

62.8

47.7

36.8

25.2

9.8

10.8

8.9

5.8

<0.0001

<0.0001

<0.0001

0.0023

15.6%

22.7%

24.2%

23.0%

(2.81)

(3.33)

(3.45)

(3.32)

(2.81)

(3.33)

(3.45)

(3.32)

(1.89)

(2.17)

(2.10)

(1.83)

* Calculated from cross-over ANOVA model.

Calculated as [(Omeprazole-Mg)Lansoprazole) Lansoprazole]100%.

Prospectively defined primary endpoint.

Number of subjects

10

Omeprazole-Mg better

Lansoprazole better

8

6

4

2

0

0.0

0.5

1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0 3.5

Treatment ratio % time pH > 4

4.0

4.5

Figure 3. Distribution of within subject treatment ratios

for the percentage time pH >4.0 in 24 h. For each subject,

a ratio (omeprazole-Mg effect lansoprazole) was calculated for percentage time pH >4. The figure is a histogram

of these ratios for all 40 subjects, with a total of 118 24h pH recordings. For 29 subjects, the ratio was >1 (i.e. the

percentage time pH >4 was greater for omeprazole-Mg

than for lansoprazole). For 10 subjects, the ratio was <1

(i.e. percentage time pH >4 was less for omeprazole-Mg

than for lansoprazole). One subject had an equal response

to both drugs.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that omeprazole-Mg 20.6 mg

provided a statistically significantly (P < 0.0001)

greater control of gastric acid production at steady state

than lansoprazole 15 mg. Both drugs were dosed daily

before breakfast, consistent with OTC label instructions,

with all 40 subjects completing the cross-over study and

98% of the 24-h gastric pH recordings included in the

data analysis. The primary variable, percentage of time

gastric pH was greater than 4.0 over 24-h on day 5 of

dosing, was significantly greater with omeprazole-Mg

(45.7%) on average than with lansoprazole (36.8%), an

absolute difference of 8.9% (P < 0.0001) and a relative

difference of 24.2%. For perspective, the absolute treatment difference of 8.9% observed in the current study is

comparable to the differences reported in a previous

study that compared percentage time gastric pH was

greater than four for esomeprazole 40 mg (58%) vs. lansoprazole 30 mg (48%), omeprazole 20 mg (49%) and

rabeprazole 20 mg (51%).6

This difference in gastric acid control for omeprazole-Mg vs. lansoprazole was evident across the 24-h

period when median gastric pH was plotted by treatment (Figure 1). Note that the median pH for omeprazole-Mg was higher than lansoprazole for a clear

majority of the post-prandial periods. The 24-h median gastric pH was maintained at a significantly higher

level for omeprazole-Mg (3.685) vs. lansoprazole

(3.058) (P < 0.0001).

At least two factors may have contributed to the

superior acid control observed for omeprazole-Mg over

lansoprazole. The first factor is the relative doses

tested in this study, which are the approved OTC doses

in the United States. Omeprazole was approved for

OTC use at the same level as the most commonly used

prescription dose )20 mg. Although more than 90% of

the prescriptions for lansoprazole were for a 30 mg

dose, the approved OTC dose of 15 mg lansoprazole is

only half of that level. A second possible contributing

factor is the relative potency of the two drugs. A

recent meta-analysis of 57 clinical studies assessed the

relative potency of marketed PPIs.8 Using omeprazole

as the test standard (relative potency 1.0), the authors

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 31, 846851

2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

O T C O M E P R A Z O L E V S . L A N S O P R A Z O L E I N A C I D C O N T R O L 851

concluded that, milligram for milligram, lansoprazole

(0.9) was relatively less potent than omeprazole.

Three previous, smaller cross-over gastric pH studies

ranging in sample size from 9 to 28 have assessed the

percentage of time gastric pH was greater than 4.0 as

a measure of the relative pharmacodynamic efficacy

of omeprazole 20 mg and lansoprazole 15 mg.911

These studies assessed the effects of omeprazole and

lansoprazole when dosed 1 h before a meal10, 11 and

after a meal.9 The current study was designed to assess

the relative efficacy of the two OTC PPIs while administering the drugs in a manner consistent with OTC

label dosing instructions. The absolute difference

between treatments (omeprazole > lansoprazole) in the

percentage time that pH was maintained above 4.0 in

these studies was between 2% to 3% in the earlier

studies10, 11 and 14% in the most recent study.9 Our

larger cross-over study completed 40 subjects and

employed a 3-period design wherein subjects dosed

with one treatment for one period and the other treatment for two periods. Our study found an absolute

treatment difference of 8.9% and a relative difference

of 24.2% in favour of omeprazole-Mg and is within

the range of previously reported results.

The distribution of within-subject omeprazole-tolansoprazole ratios for the percentage time pH was

greater than 4.0 (Figure 3), which indicates that nearly

3 of 4 subjects experienced a greater acid control with

omeprazole-Mg 20.6 mg than with lansoprazole 15 mg.

Another way to visualize the acid control treatment

REFERENCES

1 Eisen G. Epidemiology and natural history

of GERD. Am J Gastroenterol 2001; 96(8,

supplement): S168.

2 AC Nielsen SmithKlineBeecham Survey.

Profile of consumers in need: people with

sour stomachs, by demographics. Progressive Groc 1995; 74: 989.

3 Miner PB, Allgood LD, Grender JM. Comparison of gastric pH with omeprazole

magnesium 20.6mg (Prilosec OTC) o.m. famotidine 10mg (Pepcid AC) b.d. and famotidine 20mg b.d. over 14 days of treatment.

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006; 25: 1039.

4 Schubert ML, Peura DA. Control of gastric

acid secretion in health and disease. Gastroenterol 2008; 134: 184260.

Aliment Pharmacol Ther 31, 846851

2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

difference is to examine the percentage of time each

therapy kept pH above a certain level. Omeprazole-Mg

maintained a higher percentage of time above each pH

level across the entire range of pH values. We pre-specified a pH value of 4.0 for our efficacy analyses; this

value is known to be compatible with healing of gastric

damage and is well established in the literature for

studies of this type. It is noteworthy that our data indicate that the superior gastric acid control of omeprazole-Mg 20 mg vs. lansoprazole 15 mg we observed

was not dependent upon the specific pH chosen, but

was observed across the range of pH values (Figure 2).

In conclusion, this head-to-head comparison of currently available OTC PPIs indicates that omeprazoleMg 20.6 mg is more effective than lansoprazole 15 mg

with respect to 24-h gastric acid suppression.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declaration of personal interests: J. W. McRorie, L. A.

McKean, R. D. Gibb, G. N. Erasala and D. L. Ramsey are

employees and shareholders of Procter & Gamble. P. B.

Miner Jr. has received research funding from Procter &

Gamble. The authors acknowledge the assistance of Lisa

Bosch in the preparation of the manuscript. Declaration

of funding interests: This study was funded in full by

Procter & Gamble. Writing support was provided by Lisa

Bosch, an employee of Procter & Gamble. Statistical

analyses were performed by authors (R. D. Gibb, D. L.

Ramsey) who are employees of Procter & Gamble.

5 Ratkowsky DA, Evans MA, Alldredge JR.

Cross-over Experiments: Design, Analysis,

and Application. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc., 1993.

6 Miner P, Katz PO, Chen Y, Sostek M. Gastric acid control with esomeprazole, lansoprazole, omeprazole, pantoprazole, and

rabeprazole: a five-way crossover study.

Am J Gastroenterol 2003; 98: 261620.

7 Howden CW. Optimizing the pharmacology of acid control in acid-related

disorder. Am J Gastroenterol 1997; 92:

17S21S.

8 Kirchheiner J, Glatt S, Fuhr U, et al. Relative potency of proton-pump inhibitorComparison of effects on intragastric

pH. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2009; 65: 19

31.

9 Shimatani T, Inoue M, Kuroiwa T, et al.

Acid-suppressive effects of rabeprazole,

omeprazole, and lasoprazole at reduced

and standard doses: a crossover comparative study in homozygous extensive metabolizers of cytochrome P450 2C19. Clin

Pharmacol Ther 2006; 79: 14452.

10 Tolman KG, Sanders SW, Buchi KN, et al.

The effects of oral doses of lansoprazole

and omeprazole on gastric pH. J Clin

Gastroenterol 1997; 24: 6570.

11 Blum RA, Shi H, Karol MD, Greski-Rose

PA, Hunt RH. The comparative effects of

lansoprazole, omeprazole, and ranitidine

in suppressing gastric acid secretion. Clin

Ther 1997; 19: 101323.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Top Trials in Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 2nd EditionDa EverandTop Trials in Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 2nd EditionNessuna valutazione finora

- Top Trials in Gastroenterology & HepatologyDa EverandTop Trials in Gastroenterology & HepatologyValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (7)

- Relative Potency of Proton-Pump Inhibitors-ComparisonDocumento13 pagineRelative Potency of Proton-Pump Inhibitors-ComparisonTonii SoberanisNessuna valutazione finora

- Effect of Methadone Dose Contingencies ON Urinalysis Test Results of Polydrug-Abusing Methadone-Maintenance PatientsDocumento8 pagineEffect of Methadone Dose Contingencies ON Urinalysis Test Results of Polydrug-Abusing Methadone-Maintenance PatientsWao wamolaNessuna valutazione finora

- Antimicrobial Peptides in Gastrointestinal DiseasesDa EverandAntimicrobial Peptides in Gastrointestinal DiseasesChi Hin ChoNessuna valutazione finora

- Carditone Herb Clinical StudyDocumento8 pagineCarditone Herb Clinical StudyDr Sreedhar TirunagariNessuna valutazione finora

- AGA 2022 - AGA Clinical Practice Update On De-Prescribing of Proton Pump InhibitorsDocumento9 pagineAGA 2022 - AGA Clinical Practice Update On De-Prescribing of Proton Pump InhibitorsBigPharma HealtcareNessuna valutazione finora

- Clinical Assessment of The Use of Propinox HydrochDocumento8 pagineClinical Assessment of The Use of Propinox HydrochKary HuertaNessuna valutazione finora

- Miwa 2016Documento13 pagineMiwa 2016asri nurul ismiNessuna valutazione finora

- A New Approach To The Prophylaxis of Cyclic Vomiting TopiramateDocumento5 pagineA New Approach To The Prophylaxis of Cyclic Vomiting TopiramateVianNessuna valutazione finora

- Polyethylene Glycol 3350 in The Treatment of Chronic IdiopathicDocumento8 paginePolyethylene Glycol 3350 in The Treatment of Chronic IdiopathicJose SalazarNessuna valutazione finora

- Relative Potency of Proton-Pump Inhibitors of Effects On Intragastric PHDocumento13 pagineRelative Potency of Proton-Pump Inhibitors of Effects On Intragastric PHbbmguyNessuna valutazione finora

- Ppi h2 AntagonisDocumento10 paginePpi h2 Antagonismercy taniaNessuna valutazione finora

- Histopathology of Preclinical Toxicity Studies: Interpretation and Relevance in Drug Safety EvaluationDa EverandHistopathology of Preclinical Toxicity Studies: Interpretation and Relevance in Drug Safety EvaluationNessuna valutazione finora

- Proton-Pump Inhibitors Therapy and Blood Pressure ControlDocumento6 pagineProton-Pump Inhibitors Therapy and Blood Pressure ControlTeky WidyariniNessuna valutazione finora

- Article CritiqueDocumento5 pagineArticle Critiqueapi-437831510Nessuna valutazione finora

- Safety and Efficacy of Lorcaserin: A Combined Analysis of The BLOOM and BLOSSOM TrialsDocumento12 pagineSafety and Efficacy of Lorcaserin: A Combined Analysis of The BLOOM and BLOSSOM TrialsRosemarie FritschNessuna valutazione finora

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 6: Liver and GallbladderDa EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 6: Liver and GallbladderNessuna valutazione finora

- CreonDocumento12 pagineCreonNikola StojsicNessuna valutazione finora

- Double-Blind Randomized Study Comparing Brand-Name and Generic Phenytoin MonotherapyDocumento7 pagineDouble-Blind Randomized Study Comparing Brand-Name and Generic Phenytoin MonotherapySergio Guadalupe Dévora RamírezNessuna valutazione finora

- Presystemic Drug Elimination: Butterworths International Medical Reviews: Clinical Pharmacology and TherapeuticsDa EverandPresystemic Drug Elimination: Butterworths International Medical Reviews: Clinical Pharmacology and TherapeuticsCharles F. GeorgeValutazione: 1 su 5 stelle1/5 (1)

- Apt 12695Documento13 pagineApt 12695Hadi KuriryNessuna valutazione finora

- Olanzapine For The Prevention of Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and VomitingDocumento9 pagineOlanzapine For The Prevention of Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and VomitingAdina NeagoeNessuna valutazione finora

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocumento14 pagineNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptPutri Septiana PratiwiNessuna valutazione finora

- Boghossian Et Al-2017-Cochrane Database of Systematic ReviewsDocumento4 pagineBoghossian Et Al-2017-Cochrane Database of Systematic ReviewsrisdalNessuna valutazione finora

- Ijrms-12947+r+ (2) 240116 200810Documento11 pagineIjrms-12947+r+ (2) 240116 200810devanganduNessuna valutazione finora

- Pi Is 0002937805008914Documento5 paginePi Is 0002937805008914Diyah RahmawatiNessuna valutazione finora

- Efficacy of Buspirone, A Fundus-Relaxing Drug, in Patients With Functional DyspepsiaDocumento7 pagineEfficacy of Buspirone, A Fundus-Relaxing Drug, in Patients With Functional DyspepsiaIndra AjaNessuna valutazione finora

- V37-4 Art 3 pp186-193Documento8 pagineV37-4 Art 3 pp186-193wikka94Nessuna valutazione finora

- Nutrition Journal: Nutrition Support in Cancer Patients: A Brief Review and Suggestion For Standard Indications CriteriaDocumento5 pagineNutrition Journal: Nutrition Support in Cancer Patients: A Brief Review and Suggestion For Standard Indications CriteriaSunardiasihNessuna valutazione finora

- JCO-2002-de Lemos-3040-2Documento6 pagineJCO-2002-de Lemos-3040-2KabronazoNessuna valutazione finora

- 2008 - Nancy M Tofil - Histamine2receptorantagonistsvsintravenousprotonpu (Retrieved 2017-02-01)Documento6 pagine2008 - Nancy M Tofil - Histamine2receptorantagonistsvsintravenousprotonpu (Retrieved 2017-02-01)adsadassddNessuna valutazione finora

- Ondansetron Compared With Doxylamine And.13Documento8 pagineOndansetron Compared With Doxylamine And.13Satria Panca KartaNessuna valutazione finora

- Renal Pharmacotherapy: Dosage Adjustment of Medications Eliminated by the KidneysDa EverandRenal Pharmacotherapy: Dosage Adjustment of Medications Eliminated by the KidneysNessuna valutazione finora

- Part 3 - Huang Qin Tang at Yale Medical SchoolDocumento3 paginePart 3 - Huang Qin Tang at Yale Medical SchoolCarleta StanNessuna valutazione finora

- Limitations of Using A Single Postdose Midazolam Concentration To Predict CYP3A-Mediated DrugDocumento11 pagineLimitations of Using A Single Postdose Midazolam Concentration To Predict CYP3A-Mediated DrugLuciana OliveiraNessuna valutazione finora

- Gastrico Vs TranspiloricaDocumento6 pagineGastrico Vs TranspiloricaMagali FloresNessuna valutazione finora

- Itopride and DyspepsiaDocumento9 pagineItopride and DyspepsiaRachmat AnsyoriNessuna valutazione finora

- Safety and Feasability of Muslim Fasting While Receiving ChemotherapyDocumento6 pagineSafety and Feasability of Muslim Fasting While Receiving ChemotherapyIOSR Journal of PharmacyNessuna valutazione finora

- Bhumyamalaki Panchanga ChurnaDocumento7 pagineBhumyamalaki Panchanga ChurnaMulayam Singh YadavNessuna valutazione finora

- Article Wjpps 1435058037Documento10 pagineArticle Wjpps 1435058037dhananjayNessuna valutazione finora

- Pi Is 0025619611601213Documento5 paginePi Is 0025619611601213FarmaIndasurNessuna valutazione finora

- Breast-Cancer Adjuvant Therapy With Zoledronic Acid: Methods Study PatientsDocumento11 pagineBreast-Cancer Adjuvant Therapy With Zoledronic Acid: Methods Study PatientsAn'umillah Arini ZidnaNessuna valutazione finora

- Metformin Versus Acarbose Therapy in Patients With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) : A Prospective Randomised Double-Blind StudyDocumento9 pagineMetformin Versus Acarbose Therapy in Patients With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) : A Prospective Randomised Double-Blind StudyIam MaryamNessuna valutazione finora

- Presented By: Vina Yuliawati Julia Pertiwi Lizahra Maulina Preseptor: Dr. Hj. Yunita, SP. PD FINASIMDocumento26 paginePresented By: Vina Yuliawati Julia Pertiwi Lizahra Maulina Preseptor: Dr. Hj. Yunita, SP. PD FINASIMSonia jolandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Innovative in Vitro Methodologies For Establishing Therapeutic EquivalenceDocumento6 pagineInnovative in Vitro Methodologies For Establishing Therapeutic EquivalenceAnonymous 6OPLC9UNessuna valutazione finora

- Acetatode Medroxiprogesterona PDFDocumento5 pagineAcetatode Medroxiprogesterona PDFG Chewie CervantesNessuna valutazione finora

- Efficacy of Transoral Fundoplication Vs Omeprazole For Treatment of Regurgitation in A Randomized Controlled Trial-1Documento15 pagineEfficacy of Transoral Fundoplication Vs Omeprazole For Treatment of Regurgitation in A Randomized Controlled Trial-1-Yohanes Firmansyah-Nessuna valutazione finora

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 8: UrologyDa EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 8: UrologyValutazione: 3 su 5 stelle3/5 (1)

- 11 JCO-2005-Ravasco-1431-8Documento8 pagine11 JCO-2005-Ravasco-1431-8Samuel Kyei-BoatengNessuna valutazione finora

- Bazedoxifane Dan IbuprofenDocumento7 pagineBazedoxifane Dan Ibuprofendita novia maharaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Parasympathomimetics SR Pre-ProofDocumento28 pagineParasympathomimetics SR Pre-ProofaxxoNessuna valutazione finora

- Pi Is 0016508517307163Documento1 paginaPi Is 0016508517307163Ponpimol Odee BongkeawNessuna valutazione finora

- Comparative Bioavailability Study of Phenytoin inDocumento4 pagineComparative Bioavailability Study of Phenytoin inHuydiNessuna valutazione finora

- Poster Template 1Documento1 paginaPoster Template 1Jose Angel Valdez Jr.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Systematic Review: The Effects of Fibre in The Management of Chronic Idiopathic ConstipationDocumento7 pagineSystematic Review: The Effects of Fibre in The Management of Chronic Idiopathic Constipationadinny julmizaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lactobacillus Reuteri Helicobacter PyloriDocumento8 pagineLactobacillus Reuteri Helicobacter PyloriSrisailan KrishnamurthyNessuna valutazione finora

- Quality Improvement Project.Documento7 pagineQuality Improvement Project.rhinoNessuna valutazione finora

- 8 10Documento57 pagine8 10rahmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Denah LokasiDocumento2 pagineDenah LokasirahmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Guidelines VertigoDocumento16 pagineGuidelines VertigoririnNessuna valutazione finora

- Lactulose Improves Cognitive Functions and Healthrelated Quality of Life in Patients With Cirrhosis Who Have Minimal Hepatic EncephalopathyDocumento1 paginaLactulose Improves Cognitive Functions and Healthrelated Quality of Life in Patients With Cirrhosis Who Have Minimal Hepatic EncephalopathyrahmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lactulose Improves Cognitive Functions and Healthrelated Quality of Life in Patients With Cirrhosis Who Have Minimal Hepatic EncephalopathyDocumento1 paginaLactulose Improves Cognitive Functions and Healthrelated Quality of Life in Patients With Cirrhosis Who Have Minimal Hepatic EncephalopathyrahmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Template For Individual Asignment English 2015Documento1 paginaTemplate For Individual Asignment English 2015rahmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Structural Analysis Cheat SheetDocumento5 pagineStructural Analysis Cheat SheetByram Jennings100% (1)

- Mendezona vs. OzamizDocumento2 pagineMendezona vs. OzamizAlexis Von TeNessuna valutazione finora

- Certified Quality Director - CQD SYLLABUSDocumento3 pagineCertified Quality Director - CQD SYLLABUSAnthony Charles ANessuna valutazione finora

- Jerome Bruner by David R. OlsonDocumento225 pagineJerome Bruner by David R. OlsonAnthony100% (4)

- Hemzo M. Marketing Luxury Services. Concepts, Strategy and Practice 2023Documento219 pagineHemzo M. Marketing Luxury Services. Concepts, Strategy and Practice 2023ichigosonix66Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Effect of Carbon Black On The Oxidative Induction Time of Medium-Density PolyethyleneDocumento8 pagineThe Effect of Carbon Black On The Oxidative Induction Time of Medium-Density PolyethyleneMIRELLA BOERYNessuna valutazione finora

- Turn Taking and InterruptingDocumento21 pagineTurn Taking and Interruptingsyah malengNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Digest 1-4.46Documento4 pagineCase Digest 1-4.46jobelle barcellanoNessuna valutazione finora

- Criminal Law Book 2 Titles 1-8Documento146 pagineCriminal Law Book 2 Titles 1-8Minato NamikazeNessuna valutazione finora

- Nift B.ftech Gat PaperDocumento7 pagineNift B.ftech Gat PapergoelNessuna valutazione finora

- MLB From 3G SideDocumento16 pagineMLB From 3G Sidemalikst3Nessuna valutazione finora

- Mercado Vs Manzano Case DigestDocumento3 pagineMercado Vs Manzano Case DigestalexparungoNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 2: Demand, Supply & Market EquilibriumDocumento15 pagineChapter 2: Demand, Supply & Market EquilibriumRaja AfiqahNessuna valutazione finora

- Effective Leadership Case Study AssignmentDocumento5 pagineEffective Leadership Case Study AssignmentAboubakr Soultan67% (3)

- The AmazonsDocumento18 pagineThe AmazonsJoan Grace Laguitan100% (1)

- Case Presentation 1Documento18 pagineCase Presentation 1api-390677852Nessuna valutazione finora

- DLP IN LitDocumento9 pagineDLP IN LitLotis VallanteNessuna valutazione finora

- 17.5 Return On Investment and Compensation ModelsDocumento20 pagine17.5 Return On Investment and Compensation ModelsjamieNessuna valutazione finora

- How Cooking The Books WorksDocumento27 pagineHow Cooking The Books WorksShawn PowersNessuna valutazione finora

- TE.040 S T S: General LedgerDocumento32 pagineTE.040 S T S: General LedgerSurya MaddiboinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Cambridge International Advanced Subsidiary LevelDocumento12 pagineCambridge International Advanced Subsidiary LevelMayur MandhubNessuna valutazione finora

- The Relationship Between Emotional Intelligence and Job Performance of Myanmar School TeachersDocumento16 pagineThe Relationship Between Emotional Intelligence and Job Performance of Myanmar School TeachersAmadeus Fernando M. PagenteNessuna valutazione finora

- Basic English: Unit 14 Guidelines Leisure ActivitiesDocumento5 pagineBasic English: Unit 14 Guidelines Leisure ActivitiesDeyan BrenesNessuna valutazione finora

- Information Technology SECTORDocumento2 pagineInformation Technology SECTORDACLUB IBSbNessuna valutazione finora

- Caldecott WinnersDocumento1 paginaCaldecott Winnersbenanas6Nessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To SAP Business OneDocumento29 pagineIntroduction To SAP Business OneMoussa0% (1)

- Growth PredictionDocumento101 pagineGrowth PredictionVartika TripathiNessuna valutazione finora

- Financial Reporting For Financial Institutions MUTUAL FUNDS & NBFC'sDocumento77 pagineFinancial Reporting For Financial Institutions MUTUAL FUNDS & NBFC'sParvesh Aghi0% (1)

- Unit 9Documento3 pagineUnit 9LexNessuna valutazione finora

- Anatomy - Nervous System - Spinal Cord and Motor and Sensory PathwaysDocumento43 pagineAnatomy - Nervous System - Spinal Cord and Motor and Sensory PathwaysYAMINIPRIYAN100% (1)