Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Srpska Srednjovekovna Vojska PDF

Caricato da

Marko AleksićTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Srpska Srednjovekovna Vojska PDF

Caricato da

Marko AleksićCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Marko Aleksi (Belgrad)

One exceptional example of mediaeval sword find

from Southeastern Europe

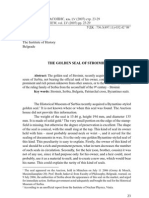

The museum in the town of Pljevlja, northern Montenegro, kept

a remarkable nding of medieval weapon. It is a sword with the two-edged

blade, hilt for one hand and mushrooms shaped pommel. This sword is a sole

nd, which means that data or the archaeological context that could directly or

indirectly indicate the time or circumstances under which this object fall to soil

are missing. According to the information from museum documentation, sword

was discovered by chance at the fort of Pirlitor at the mountain Durmitor in 19561.

The basic features of the sword hilt for one hand, slender blade with a long and

narrow fuller and long and straight cross-guard generally refer to the typological

characteristics that were present in much of Europe in the 11th and 12th century.

Those general characteristics of swords from Pirlitor could be best understood

as the youngest stage in the development of spate the type of weapon that was

dominant in most of the continent during the early middle Ages.

The sword is preserved almost in its entirety, and apart that the grip,

which was of an organic material, is missing, possibly only missing is the very top

of the blade in the length of less than one centimeter. Blade is the right, doubleedged and moderate to severe narrowing slightly towards the top. The sword is

forged of steel, and on both sides of the blade there is an ornament made by

inlaying of bronze wire. The total measured length of the weapon is 101.5 cm of

which the length of the blade is 88, and of hilt is 13.5 cm. Maximum width of the

blade, under the cross-guard, is 4.5 cm and 60 cm from it, 3.4 cm. The fuller is

72 cm long while its maximum width is 1.2 cm, and 40 cm from the cross-guard

it is 1 cm width. Cross-guard is straight, with square-section and its length is

26 cm, while its thickness is 0.8 cm. Tang of the hilt is 10 cm long. Pommel is

2.6 cm height, 4.8 cm width and 2.4 cm thick. On both sides of the blade, there

are ornaments in the form of circular medallions and a long tendrils. Medallions

have a diameter of 3.2 cm and are located about 7.5 cm from cross-guard, while

the tendrils, in a form of series of spiral motifs, 64 cm long. On the one side of

the blade the spiral ornament is of a simple, geometric shapes, 0.8 cm width, and

from the other side there is a series of simple oral motifs, about 0.7 cm width.

By its form, pommel of sword from Pirlitor mach with Oakeshotts type

B which is dated in the 11th and 12th century (Oakeshott 1981, 93). In the division

1 I thank Mr. Radoman Risto Manojlovic which has enabled me to personally review this sword during my

stay in Pljevlja in August 2009.

43

44

One exceptional example of mediaeval sword nd from Southeastern Europe

of the pommel shapes which was made by Alfred Gajbig, this shape corresponds

to his Combinationtype 15 III, which is dated from the second half of the 10th to

the third quarter of the 12th century (Geibig 1991, 66-68, 146-147, 151). Although

the shape of this pommel corresponds exactly to this type as it is conrmed also

by the relationships of all three dimensions of pommels, for the dimensions of the

pommel of the sword from Pirlitor can be said that are small, i.e. that are in all

three parameters below the values measured by Gajbig for this type (Table 1).

Sword

Pommel

width

(PW)

Pommel

height (PH)

PW/PH

PH/PT

PW/PT

Pirlitor

4.8

2.6

1.85

1.08

Geibig 15 III

5.17

2.84

1.661.97

0.881.2

1.782.36

Tab. 1. Dimensions of pommel of sword from Pirlitor and Geibigs Combination type 15 III.

Blade of the sword from Pirlitor is very slender, with a fuller which

occupies about four-fths of its length and which with is small, as well the width

of the blade. Such blades of slender silhouette Oakeshott marked as type XI and

dated its greatest popularity in the 12th century, altrought they were produced in

something smaller number in the previous and next centuries (Oakeshott 1981,

31). By typology of Alfred Gajbig, this blade would belonged to his type 9 which is

also dated in the 12th century (Geibig 1991, 153-154, Abb. 40).

Mushroom-shaped pommels of Oakeshotts type B, as well as those of

lens-shaped forms which are marked as type A, are the most common form of the

pommels on the European swords from around the end of the 10th to 12th century.

Generally speaking, older specimens of swords with pommels of type A and B

usually have blades of Oakeshotts type X, while the younger specimens have

mostly blade-types Xa and XI. These circumstances generally indicated that the

sword from Pirlitor belongs to the younger specimens of swords with pommels of

type B, which would generally indicate the 12th century.

The youngest specimens of lense- and mushrom-shaped pommels (types

A and B), from about the second half of the 12th century, are often characterized

by a slightly larger size than usual for these types (Aleksi 2007, 37-38). These

metrological variations of late pommels of types A and B can be best understood

as a consequence of increase of the general size of swords at the time. In addition

to blades, which shows a mild tendency of increasing their length which also

resulted in the increase of their weight, the period around the second half of the

12th century is also characterised for the occurrence of extended hilts, for oneand-a-half hand (Oakeshott 1981, 43-45). In contrast to these general tendencies

in the development of a European sword in the second half of the 12th century,

Marko Aleksi

45

hilt of Durmitor sword is for one hand, and his pommel-type B is remarkably

small. These characteristics are especially important because this sword, by all its

typological characteristics, shows a clear relationship with the general tendencies

of European swordsmithies of the time.

In contrast to the small dimensions of the pommel and hilt for one hand,

the extremelly long cross-guard is indicating the time around the nal decades

of the 12th or even the rst decades of the 13th century. According to its value of

26 cm, it is among some of the largest cross-guards which are older than 13th

century. As examples of some of the earliest cross-guards whose length exceeds

25 cm, can be mentioned a sword from the river Ljubljanica, site Crna Vas, in

Slovenia (Nabergoj 1997, 224-300, 262, 263, cat. no 66.1, g. 38a, pl. 18:2. Crossguard lenght is 26 cm) or, for example, from unknown sites from the Hungarian

National Museum in Budapest (Gosek 1984, 174, cat. 460, pl. XXVIII:2. Lenght

of this cross-guard is 27.7 cm) and in the Military Museum in Belgrade (Petrovi

1976, 210, g. 2; 1996, 149, g. 6,; 1993, 8, 24, cat. 5. Cross-guard

lenght is 27 cm) and from the site Seehausen in upper Bavaria (Seehausen am

Staffelsee, Geibig 1991, 53, cat. No 47, pl. 33. Lenght of cross-guard is 26.6 cm).

All of these swords are, however, dated to the rst half or mid-13th century. This

is even more interesting becouse the length of the hilt of the Durmitor sword

is small, for one hand, causing the entire length of the weapon is just slightly

larger than one meter, which the overall silhouette of weapons makes very crossshaped.

The lenght of the cross-guard as a features of the sword which could

indicate the time of theirs production was considered in a many of ways.

However, this process could be followed up in a general terms. Alfred Gajbig

made a general framework of the lenghts of the cross-guards during the period

9-13 century. He noted that at the beginning of this period their maximum length

does not exceeded 13-14 cm, during the 10th century is was not more than 16 cm,

and in the 11th and 12th century appears the cross-guards whose length can reach

20 cm and even more. The greatest length of the cross-guards, and up to 28 cm,

reaching swords from the end of the 12th and the 13th century. As it can be seen

from this outline of the calculation of this parameter, the length of the Durmitor

sword cross-guard corresponding to the values that are characteristic for the

youngest part of this period, and that is the late 12th and 13th century. In relation

to this it should be noted that, despite the fact that from the middle of 13th century

in Europe emerging swords with hilts long enough for both hands, i.e. the twonaded swords in the true sense of the word, the tendency of increasing the length

of cross-guards almost stopped. The largest number of cross-guards from the 14th

and 15th century were long between 20 and 25 cm and rarely surpass this value.

In any case, we could conclude that this extremely long cross-guard of Pirlitor

sword, whose value exceeds 25 cm, is feature that almost does not allow its dating

before around the mid 12th century, and even for this period is to some extent

an exception.

46

One exceptional example of mediaeval sword nd from Southeastern Europe

Basic typological features of the sword from Pirlitor, particularly its blade

type, points to the rst half or the middle of the 12th century. Small size of its

pommel and grip which is still for the one hand, indirectly referring to its dating

prior to the rst decades of this century. On the other hand, extremely long crossguard chronologically refers to the second half of 12th or even the rst decades

of the 13th century. However, considering that the length of the cross-guard is

chronologically secondary criterion, and the fact that nding place of the sword

and some elements of its decoration allow the assumption that it originates

from the workshops that are not strictly followed all typological tendencies of

the Western swords of this time, this criterion could be relatived as sole younger

chronological indications. Therefore, the sword could be primarilly dated to the

decades around the middle of the 12th century.

***

Sword from Pirlitor bears an ornament, inlayed with yellow metal wire,

which covers a large part of his blade. Ornamet on both sides consist of circular

medallion and decorative long tendril. The medallions are the representations of

faces framed with four wings that match the performance of Cherub characteristic

for Byzantine artistic tradition. Unlike the Byzantine art, in which the Cherub is

presented only in this way, in Western Europe this, one of the supreme angel, is

portrayed as a gurative representation, usually as a boy. Four wings are clearly

visible on both medallions, and the eyes on the face of an angel in the center of

the representation can be detected in one of them.

Figure and other more complex motifs in the medallion are extremely

rare motif on medieval swords. The elements of circular medallions motif of

medieval swords may be required in simple signs which are inscribed within

a circle. The most numerous are the representations of the cross inscribed in

a circle, and is not a rare case of letters, usually the letter S, inscribed in a circle.

Sometimes inscribed cross may be more or less complex or stylished, and there

are also examples of oral motifs, owers or rosettes, in medallions. A unique

example is the sword discovered in the River Danube at the island Tahi, not far

from Budapest, which has, inlayed by a yellow and silver wire, representations

of female gure and owers on one side of the blade, while on the other, there

are two medallions with motifs of rosettes2. As an example of the medallion with

more complex representation can be quoted the blade from an unknown site that

is housed in a museum in Komarno, south Slovakia3. On one side of the blades,

2 Hungarian National Museum, Budapest (inv. nr. 67.8521). The sword has a pommel of type A. It should

be mentioned that hilt length and blade length of this sword is close to those of the sword from Pirlitor

(L = 98.1 cm; BL = 84.7 cm; HL = 13.4; TL = ca 9.8 cm). The sword is dated to the 13th century (Gosek

1984, 173, cat. 443).

3 Danube Museum in Komrno (inv. nr. III-2062). Ruttkay 1975/76, 165, 198, 203, 278, Abb. 13:1, 25:1,

27:3 a, b.

Marko Aleksi

47

inlayed with bronze wire, there is a representation of an eagle in the medallion

and letters TADS, and the other side shows a lion in a medallion, letters NIC and

latin cross. Based on these representations, which are actually heraldic motifs,

sword is attributed to the Czech king Ottokar II (1253-1278) (Gosek 1984, 141,

cat. 50), (Fig. 3).

In contrast to the obvious Christian symbolism, the representation of

Cherub on sword from Pirlitor is a unique phenomenon so far. Cherub is one

of the highest rank heavenly angels in Christianity. The only concrete sword

mentioned in the Bible is a aming sword. When Adam and Eve expelled from

Paradise, Cherub took the aming sword and stood at the entrance of heaven

preventing entry into it (The book of Genesis, 1 Book of Moses, chapter 3, verse

24). Crucial importance of Christianity for European medieval society is reected

in numerous representations of the cross, religious inscriptions and other

Christian motifs on medieval swords. Considering the importance of Cherub

in the Christian tradition that could be easily and obviously be connected with

a only concrete sword from Bible, the fact that nding from Pirlitor is for now

only one which bears such motif, suggests its exellence.

Decorative motif of long tendrils on the blade is not so rare on the

mediaeval swords, but their number is not too large. Geometric ornament on

one side of the blade of the sword from Pirlitor, as intertwined with a series of

S-motives, is quite simple. Ornament on the other side of the blades consists of

a series of trifoil oral motives which make tendrils. As an analogy for this motif,

it may be cited two ndings from eastern Germany (Gosek 1984, cat 138, 173). In

these cases, on the other side of the blade is a long Latin inscription. The fact that

this complex and long ornament on the sword from Pirlitor do not follow the latin

letters, which is a common case with similar ndings in Europe, could possibly

also indirectly indicate the origin of this ornaments from the Byzantine cultural

tradition. However, in this case remains evident effort of artists to follow, by this

motif, the general aesthetic and symbolic principles of decoration of Western

swords of this time.

Based on morphological analysis of this weapon it can be concluded that

according to the typological characteristics, the Pirlitor sword belongs to the

general Western European traditions of sword production. On the other hand,

the representation of Cherub in the Byzantine and not Western artistic tradition,

could indicated that the sword was decorated by an artist from the East or that it

was a result of the wish of its owner. The fact that this is a high quality art work,

indicate that the artist most likely belonged to some signicant cultural center.

Based on these circumstances, we may conclude that the sword from Pirlitor is

very representative object, in fact, one of the most lavish 12th century swords from

this region. How such luxurious and unique object came to this epic highlands?

48

One exceptional example of mediaeval sword nd from Southeastern Europe

***

Pirlitor medieval fortress, where the sword was found, is located on the

left bank of the middle ow of the river Tara. This is a central part of the gorge

of river Tara, the largest gorge in Europe and second in the world (after the

Colorado River canyon in the U.S.). Pirlitor fort, the most famous fortress of the

Serbian mediaeval epics, is situated on the hill, above the left bank of the Tara

River gorge. It lies on the route of the Roman and medieval road that went from

the Adriatic coast, via Onogot (roman Anagastum, todays Niki), arrived to the

area Jezera, and then, crossing the river Tara, goes to the Pljevlja and further to

the north in the Balkan hinterland. One of the two main roads which was used

by caravans of the Dubrovnik merchants during the Middle Ages, went to the

interior of Serbia using this route and was called via Jesera or via Anagasti

( 1978, 311). The dominant position of the Pirlitor fortress, close the place

where the road crossed the river near the present village Lever Tara, indicate

that its main role was to control this ancient communication. In fact, on the left

side of this part of the river ow, in an area which was called Jezera (Lakes) in

Middle Ages, Pirlitor is only known fortied place (Mijovi, Kovaevi 1975, 126;

Srednjevjekovni... 2004, 36-37). The historical Pirlitor is not mentioned under

this name, but in the area Jezera in 1399 is mentioned the court of the Bosnian

nobleman Sandalj Hranic and in the Jezera took place the negotiations between

the Sandaljs sucesor, Herceg Stjepan Vukic Kosaa (by which the Herzegovina

got its name) and Dubrovnik in 1453 (Mijovi, Kovaevi 1975, 126; irkovi

1964, 202). It is most likely that the court and place of negotiation are the same

site and that it was in fortress Pirlitor or in its vicinity.

Area of River Tara belonged to the core territory of early mediaeval

Serbia. The boundary between the two major Serbian early mediaeval states,

Dioklea and Rascia, in 11th century was a little further south from Jezera, in

the area between the rivers Tara and Piva (... 1981, 162, fn. 14 .

). One of the few writen evidences about this area in early middle ages

is from the dokument called Chronicle of the Priest of Dioclea or Gesta Regum

Sclavorum that describes the territory of Dioclea from the time of king Bodin

(1081-1099). It is in this area is mentioned only upa (counties) Komarnica

(Comarniza, Comerniza), which was undoubtedly located in the region of river of

the same name, right (northern) tributary of the River Piva ( 1928, 327,

453; 2009, 118-119). However, the area Jezera, including the fortress

Pirlitor, is located outside of the presumed territory of this counties, northwest

from it. In todays city Mojkovac, about 40 kilometers upstream the river Tara,

was situated Brskovo, the important mine of mediaeval Serbia, but historical data

about it comes just from 13th century.

Marko Aleksi

49

There is a possibility that one signicant military conict took place in this

area, and just in time when the sword could reach into the ground. It is a battle

on the river Tara, in which the Byzantine emperor Manuel Comnenus defeated

the joint Serbian and Hungarian troops under the command of Serbian grand

upan Uro II in 1150 ( ... 1971, 33, fn. 65 . ; about

use of swords in this batle: 2010). This battle has attracted much

scientic attention and today, there is no single opinion on whether the battle

took place on the river Tara in Montenegro, or near another river of the same

name, tributary of the river Kolubara near the todays town Valjevo in Serbia, some

250 km northern ( 1976). Anywhere that was the site of this battle,

it and the military operations that followed, could be an rare example of

circumstances under which this remarkable sword could reach such areas. The

old Roman road and place of its crossing the river Tara near the fortication of

Pirlitor, had a denite strategic importance also in the 12th century and becouse

of that could be the place which was used by the armies.

Although there is no much knowledge about where the battle took place and

its surviving material traces are missing, there is one item of military equipment

that could possibly be linked to it. It is a gilden spur which was discovered in the

tomb of a upan of Trebinje, Grd ( around 1170) at the site Poljice near Trebinje

in eastern Herzegovina (Aneli 1962, 173-175; about the time of the death of

the upan Grd 1963, 256-257; 2006, 459-460)4. Grd is

identied with the upan Grdea (Gerdesa, Gerdessa) that was mentioned as a

witness in two charters of the prince of Zachlumia (Zahumlje), Desa from 1151

( 1928, 201, 237-238; ivkovi 2009, 327; Foreti 1952. upan Grdea

is mentioned and in one another charter, of some ban Slavogost, 1928,

191-192; 2009, 327). upan Grdea () which is mentioned

as a participant in the battle on the river Tara is usually identied with the same

Gerdes(s)a and Grd from Herzegowina ( ... 1971, 33, fn. 65,

. ). Regardless of whether the sword from Pirlitor and a golden spur from

Herzegovina actually met during the Battle of the 1150 in the gorge of Tara, or

not, remains the fact that these are two unique ndings of representative weapons

and military equipment from this area and from the same period.

This sword could reach the slopes of the Tara gorge and in various other

circumstances. The old Roman road did not used only by the armies, but also, above

all, by traders, people who had also, in certain circumstances, be in position to

carry such a luxury object. During the very tumultuous intensive political turmoil

in Doclea and Rascia during the 12th century, this road could have been used by

some of the many members of royal families and high nobles who, in the struggle

for power, moved between those Serbian states with armies or just with theirs

escorts (more about these tumultuous political circumstances: 2006,

4 This tombstone is now kept in the Museum of Herzegovina, Trebinje: http://muzejhercegovine.org/

pages/inline2/arheologija/zupan_grd.htm [12.05.2010].

50

One exceptional example of mediaeval sword nd from Southeastern Europe

458-461). The lack of historical sources about this areas in 12th century does not

exclude the possibility that the Pirlitor fortress, which is still not archaeologically

investigated, could be signicant strategic of administrative center even in the

12th century. The sword from Pirlitor is an exceptional archaeological nd from

the time in which the political, cultural and other impacts from the West and

East were dynamically intertwined in this region. This unique object represent

a vividly testimony of the intertwining of these inuences.

Bibliography

Sources:

...

1971

(Fontes Byzantini historiam

populorum Jugoslaviae spectantes), T. 4, ed. G. Ostrogorsky, F. Barii, .

.

1928 , .

Literature:

Aleksi M.

2007 Mediaeval Swords from Southeastern Europe, Belgrade.

Aneli P.

1962

Mamuza trebinjskog upana Grda, Glasnik zemaljskog muzeja u Sarajevu, 17,

173-175.

.

1976

, (Setzenitza, Strymon et Tara dans

loeuvre de Jean Kinnamos), (Byzantine Studies), 17, 69-75.

irkovi S.

1964

Herceg Stefan Vuki Kosaa i njegovo doba, Beograd.

.

1978

(Dubrovniks Medieval Caravan

Trade), [in:] . , , .

.

2010 Srpsko naoruanje i taktika u delu Jovana Kinama, Vojno-istorijski glasnik, 2, 9-19

Foreti V.

1952

Dvije isprave Zahumskog kneza Dese o Mljetu iz 1151. godine, Anali Historijskog Instituta JAZU, 1, 65-72.

Geibig A.

1991

Geibig, Beitrge zur morphologischen Entwicklung des Schwertes im Mittelalter, Neumnster.

Marko Aleksi

51

Gosek M.

1984 Miecze rodkowoeuropejskie z X-XV w., Warszawa.

...

1981

1, ed. S. irkovi, .

Mijovi P., Kovaevi M.

1975

Gradovi i utvrenja u Crnoj Gori (Towns and fortresses in Montenegro), Beograd.

.

1993

XIV XX , catalogue, .

Oakeshott R.E.

1981

The Sword in the Age of Chivlary, London.

Nabergoj T.

1997

[in:] D. Svoljak, P. Bitenc, J. Isteni, T. Knic, T. Nabergoj, Novo gradivo v Arheolokem

oddelku Narodnega muzeja v Ljubljani (pridobljeno v letih 1987 do 1993), Varstvo

spomenikov 36/94-95, Ljubljana, 224-300.

Petrovi .

1976

Dubrovako oruje u XIV veku, Beograd.

1996

XII-XIV , [in:] , ed. S. Terzi .

. .

1963

, (Byzantine Studies), 8 (1), 255-259.

Ruttkay A.

1975/76 Waffen und Reiterasrstung des 9. bis zur ersten halfte des 14. Jahrhunderts in der

Slowakei I, Slov. Arch. XXIII-1, 1975, 119-216, XXIV-2, Nitra 1976, 245-395.

Srednjevjekovni...

2004 Srednjevjekovni gradovi Crne Gore (Medieval Towns of Montenegro), Kotor.

.

2006 XII (Dioclea between

Rascia and Byzantium in the rst half of the twelfth century),

(Byzantine Studies), 43, Beograd, 359-460.

ivkovi T.

2009 Gesta Regum Sclavorum, Beograd.

52

One exceptional example of mediaeval sword nd from Southeastern Europe

Fig. 1. Sword from site Pirlitor,

northern Montenegro, Museum

in Pljevlja (phot. M. Aleksi).

Marko Aleksi

Fig. 2. Sword from site Pirlitor, northern Montenegro, Museum in Plljevlja

(phot. M. Aleksi).

53

54

One exceptional example of mediaeval sword nd from Southeastern Europe

Fig. 3. Sword of king Ottokar II (1253-1278), Danube Museum in Komrno (pic. M. Aleksi).

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Late Roman KnivesDocumento6 pagineLate Roman KnivesMárk György Kis100% (1)

- Medieval Armor in BulgariaDocumento14 pagineMedieval Armor in BulgariaMatthew LewisNessuna valutazione finora

- Arma AleksicDocumento19 pagineArma AleksicMatthew LewisNessuna valutazione finora

- Gift of The River A Late Bronze Age SworDocumento10 pagineGift of The River A Late Bronze Age SworDjura RehNessuna valutazione finora

- Marko Aleksic - Swords With Pommels of Type NDocumento26 pagineMarko Aleksic - Swords With Pommels of Type NungernsternbergNessuna valutazione finora

- Iron Spearhead and Javelin From Four CrossesDocumento4 pagineIron Spearhead and Javelin From Four CrossesStanisław DisęNessuna valutazione finora

- Evidence From Dura Europos For The Origins of Late Roman HelmetsDocumento29 pagineEvidence From Dura Europos For The Origins of Late Roman Helmetssupiuliluma100% (1)

- Illustratedhisto 00 DemmrichDocumento616 pagineIllustratedhisto 00 DemmrichVincenzoM1980100% (1)

- AralicaIlkicKriznicaNin2012 ENGL NMP LEKT SH NMP FINAL NMPDocumento16 pagineAralicaIlkicKriznicaNin2012 ENGL NMP LEKT SH NMP FINAL NMPNina Matetic PelikanNessuna valutazione finora

- Sword and Dagger Pommels Associated With Crusades Part I The Metropolitan Museum Journal V 46 2011Documento12 pagineSword and Dagger Pommels Associated With Crusades Part I The Metropolitan Museum Journal V 46 2011leongorissenNessuna valutazione finora

- Roman Belt-Fittings From BurgenaeDocumento14 pagineRoman Belt-Fittings From BurgenaealexandrecolotNessuna valutazione finora

- Sandars 1993 - Later Aegean Bronze SwordsDocumento46 pagineSandars 1993 - Later Aegean Bronze SwordsMaria-Magdalena Stefan100% (1)

- Armour of The Goths in The 3rd 7th CentuDocumento6 pagineArmour of The Goths in The 3rd 7th CentuCorrado ReNessuna valutazione finora

- Sarmatian Swords 2 - ROMECDocumento12 pagineSarmatian Swords 2 - ROMECkulcsarv100% (2)

- Strojimirov PecatDocumento6 pagineStrojimirov PecatКонстантин БодинNessuna valutazione finora

- The Medieval SwordDocumento2 pagineThe Medieval SwordSteven Till100% (3)

- Ancient Brimmed Helmets As Introduction To Medieval Kettle Hats? (2021, Fasciculi Archaeologiae Historicae) by Daniel GoskDocumento14 pagineAncient Brimmed Helmets As Introduction To Medieval Kettle Hats? (2021, Fasciculi Archaeologiae Historicae) by Daniel GoskJohnNessuna valutazione finora

- Military Sabers of The QingDocumento9 pagineMilitary Sabers of The QingpaulijuhaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Historical Evolution of Swords, Knives, DaggersDocumento2 pagineHistorical Evolution of Swords, Knives, DaggersGurpreet SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Stojimirov Zlatni PecatDocumento7 pagineStojimirov Zlatni Pecatvisual18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Byzantine Lamellar ArmourDocumento9 pagineByzantine Lamellar ArmourGuillermo Agustin Gonzalez Copeland100% (1)

- The Golden Seal of StroimirDocumento8 pagineThe Golden Seal of Stroimirtibor zivkovic100% (1)

- The Serpent in The Sword: Pattern-Welding in Early Medieval SwordsDocumento6 pagineThe Serpent in The Sword: Pattern-Welding in Early Medieval SwordsMariella GiorginiNessuna valutazione finora

- FAB 02.26. Spasova, D. - The Roman Legionary From Ohrid CitadelDocumento13 pagineFAB 02.26. Spasova, D. - The Roman Legionary From Ohrid Citadelboshko angelovskiNessuna valutazione finora

- Za Tipologiju StrelicaDocumento14 pagineZa Tipologiju StrelicaSasa ZivanovicNessuna valutazione finora

- Dalian Forklift CPCD Cpd20 Parts Manual ZhenDocumento22 pagineDalian Forklift CPCD Cpd20 Parts Manual Zhenjerryroberts051291ixe100% (25)

- What S The Bloody Point Swordsmanship inDocumento22 pagineWhat S The Bloody Point Swordsmanship inGianfranco BongioanniNessuna valutazione finora

- Handbook Archery App 1Documento7 pagineHandbook Archery App 1Deniver VukelicNessuna valutazione finora

- A Fourteenth Century Sword From MoldovenDocumento6 pagineA Fourteenth Century Sword From MoldovenFrancsico FerrerNessuna valutazione finora

- Steel Viking SwordDocumento6 pagineSteel Viking Swordsoldatbr4183Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Evolution of Splint ArmourDocumento36 pagineThe Evolution of Splint ArmourpimpzillaNessuna valutazione finora

- Short Owerview of Roman SwordsDocumento7 pagineShort Owerview of Roman SwordsVinnyNessuna valutazione finora

- Sabre FencingDocumento4 pagineSabre FencingasdjhgfghNessuna valutazione finora

- Playing by The Rules: Swords and Swordfighters in The Mycenaean Society, Alexandra TarleaDocumento26 paginePlaying by The Rules: Swords and Swordfighters in The Mycenaean Society, Alexandra TarleaFlorea Mihai StefanNessuna valutazione finora

- Tsubajapaneseswo00coop BWDocumento48 pagineTsubajapaneseswo00coop BWPRILK2011Nessuna valutazione finora

- 15th Century Sheaths From The City of LeidenDocumento14 pagine15th Century Sheaths From The City of LeidenHugh KnightNessuna valutazione finora

- And Other European Polearms 1300-1650: The HalberdDocumento17 pagineAnd Other European Polearms 1300-1650: The HalberdBiciin MarianNessuna valutazione finora

- Medieval ArrowsDocumento11 pagineMedieval Arrowsbbs_silvaNessuna valutazione finora

- Knightly Art LibreDocumento7 pagineKnightly Art LibreIacob GabrielaNessuna valutazione finora

- Pozlaćena Fibula SirmiumDocumento12 paginePozlaćena Fibula SirmiumPero68Nessuna valutazione finora

- New Light On The Old Bow #1 PDFDocumento17 pagineNew Light On The Old Bow #1 PDFFERNANDITONessuna valutazione finora

- Applications of Physics To ArcheryDocumento11 pagineApplications of Physics To ArcheryLuribayNessuna valutazione finora

- Bullet Dents in Armour Proof Marks or BaDocumento37 pagineBullet Dents in Armour Proof Marks or BaAirish FNessuna valutazione finora

- The Medieval Archer's Reading ListDocumento9 pagineThe Medieval Archer's Reading ListAlfieNessuna valutazione finora

- A Lead Sling Bullet of The Macedonian King Philip V (221 - 179 BC) - Metodi ManovDocumento11 pagineA Lead Sling Bullet of The Macedonian King Philip V (221 - 179 BC) - Metodi ManovSonjce Marceva100% (1)

- Middle Byzantine Period Weapons From TheDocumento20 pagineMiddle Byzantine Period Weapons From TheVladan VidosavljevićNessuna valutazione finora

- A. Badescu, M. Negru, R. Avram - The Amphorae of Kapitan II Type in Dacia (RCRF Acta 38, 2003, 209-213)Documento6 pagineA. Badescu, M. Negru, R. Avram - The Amphorae of Kapitan II Type in Dacia (RCRF Acta 38, 2003, 209-213)Dragan GogicNessuna valutazione finora

- Clad in Steel - The Evolution of Plate Armor in Medieval EuropeDocumento42 pagineClad in Steel - The Evolution of Plate Armor in Medieval EuropeRWWT RWWTNessuna valutazione finora

- Mamuka Tsurtsumia: Komunikaty - AnnouncementsDocumento14 pagineMamuka Tsurtsumia: Komunikaty - AnnouncementsTobi VlogNessuna valutazione finora

- Haithabu Knives PDFDocumento6 pagineHaithabu Knives PDFTheo PrinsNessuna valutazione finora

- ARCHERY Magyar Archery PDFDocumento7 pagineARCHERY Magyar Archery PDFDoso DosoNessuna valutazione finora

- ELTE Bölcsészettudományi Kar Történettudományi Doktori Iskola Régészet ProgramDocumento6 pagineELTE Bölcsészettudományi Kar Történettudományi Doktori Iskola Régészet ProgramMassimo CenniNessuna valutazione finora

- Products of The Blacksmith in Mid-Late Anglo-Saxon England, Part 2Documento16 pagineProducts of The Blacksmith in Mid-Late Anglo-Saxon England, Part 2oldenglishblogNessuna valutazione finora

- Milanese XVDocumento12 pagineMilanese XVMatthew LewisNessuna valutazione finora

- Weapons of The 17th CenturyDocumento17 pagineWeapons of The 17th CenturyAna TorresNessuna valutazione finora

- Hladno Oružje Iz Bosne I Hercegovine U Arheologiji Razvijenog I Kasnog Srednjeg Vijeka (Cold-Steel Mediaeval Weapons From Bosnia and Herzegovina)Documento27 pagineHladno Oružje Iz Bosne I Hercegovine U Arheologiji Razvijenog I Kasnog Srednjeg Vijeka (Cold-Steel Mediaeval Weapons From Bosnia and Herzegovina)pomel777767% (3)

- Longsword and Saber: Swords and Swordsmen of Medieval and Modern Europe: Knives, Swords, and Bayonets: A World History of Edged Weapon Warfare, #9Da EverandLongsword and Saber: Swords and Swordsmen of Medieval and Modern Europe: Knives, Swords, and Bayonets: A World History of Edged Weapon Warfare, #9Valutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- The Dates of Variously-shaped Shields, with Coincident Dates and ExamplesDa EverandThe Dates of Variously-shaped Shields, with Coincident Dates and ExamplesNessuna valutazione finora

- V Ivanishevic HeradlikaDocumento22 pagineV Ivanishevic HeradlikaSnezhana FilipovaNessuna valutazione finora

- Milanese XVDocumento12 pagineMilanese XVMatthew LewisNessuna valutazione finora

- Pravilnik o Utvrdjivanju Telesnih OstecenjaDocumento18 paginePravilnik o Utvrdjivanju Telesnih OstecenjaMatthew LewisNessuna valutazione finora

- Pravilnik o Utvrdjivanju Telesnih OstecenjaDocumento18 paginePravilnik o Utvrdjivanju Telesnih OstecenjaMatthew LewisNessuna valutazione finora

- Coat of Plates BulgariaDocumento16 pagineCoat of Plates BulgariaMatthew LewisNessuna valutazione finora

- Janos Thuroczy Chronicle of The Hungarians Medievalia Hungarica Series, V. 2 1991 PDFDocumento235 pagineJanos Thuroczy Chronicle of The Hungarians Medievalia Hungarica Series, V. 2 1991 PDFMatthew Lewis75% (4)

- Dj. Petrovic Dubrovacko Oruzje U XIV VekuDocumento116 pagineDj. Petrovic Dubrovacko Oruzje U XIV VekuMatthew Lewis25% (4)