Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Chen - Teachers As Change Agents PDF

Caricato da

Hidayah RosleeTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Chen - Teachers As Change Agents PDF

Caricato da

Hidayah RosleeCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Teachers as Change Agents: A Study of

In-Service Teachers' PracticalKnowledge

Christine Chen

Association for Early Childhood Educators

Independent Researcher-Learning Society, Singapore

This study investigates in-service early childhood teachers' "practical knowledge"

(Elbaz, 1981) in implementing changes in the classroom in the Republic of Singapore. In Singapore, many early childhood classrooms are teacher directed, where learning takes place in

large groups. As part of the in-service teacher education program, a learner-centered

practicum required teachers to visualize how they can include children's choice through designing learning corners and implementing small group learning. This investigation unveils how

teachers used their "practical knowledge" to implement change and documents evidences of

the change after 3 to 5 years of its initial implementation. It also highlights conditions for

change and offers suggestions to policymakers, curriculum designers, and teacher educators

in educating for change.

ABSTRACT:

This study investigates the "practical knowledge" (Elbaz, 1981) of 17 early childhood

teachers in preschool and child care centers. It

was conducted in Singapore, an island republic, which is about the size of Manhattan. In

Singapore, early childhood is not part of compulsory education that starts when the child

turns seven. As a result, preschools and child

care centers are privately or community

funded.

In terms of teacher education, teachers of

to

1st 12th graders receive their teacher education from the National Institute of Education at the Nanyang Technological University. However, for preschool and child care

teachers, there are about 21 training agencies

to choose from, most of which are private

agencies. Since all three universities in Singapore do not have the Bachelor in Early Childhood Education program, teachers attain

their bachelor's degrees with.Australian universities that fly their professors to Singapore.

However, this is a recent phenomenon, because only since 2000 have teachers been required to have a diploma in teaching (an associate degree equivalent). Prior to that time,

preschool and child care teachers were required only to have about 300 hours of inservice teacher education. Today many professionals in the field are pursuing their

bachelor of education degree not as a requiremeni but as part of their personal and professional development.

This study examined teachers in the inservice program for their diploma in teaching.

These individuals had been teaching for a

number of years after completing their 300

hours in teacher education. As a result, they

come into the program with views quite different from that of what they are expected to

learn. Generally, these teachers come from

early childhood settings that are teacher directed with children learning in large groups.

Therefore, getting teachers to include student-

Address correspondence to: Christine Chen, 50 Bayshore Rd., 4108-05 Bayshore Park, Singapore 469977, Republic of Singapore. E-mail: chchl225@gmail.com.

10

Action in Teacher Education Vol. 26, No. 4

Teachers as Change Agents

centered learning requires them to change

their worldview and become change agents.

Teachers as Change Agents

Many researchers have addressed the issue of

teachers as change agents. According,to Hoban

(2002), "change is in essence, learning to do

something differently, involving adjustments to

many elements of classroom practice" (p. 39).

However, educating teachers as change agents

is a challenge. Lane, Lacefield-Parachini, and

Isken (2003) share their concern as they write

about student teachers and novice teachers as

change agents. They believe that finding ways

to educate teachers so that they "see themselves

as capable of generating substantive change has

been difficult" (p. 55).

11

Dewey (1916/1997) addresses this challenge w.ith his view of the self as being dynamic. Teachers, being dynamic, have the capability of acquiring the quality of plasticity.

Plasticity is "the ability to learn from experience; the power to retain from one experience

something which is of avail in coping with the

difficulties of a later situation" (p. 44). He

adds that "interest, concern, mean that self

and world are engaged with each other in a developing situation" (p. 26) and that "personal

attitudes" toward thinking and acting in the

world (Dewey, 1933, pp. 29-34) paint the image of teachers as active agents of change.

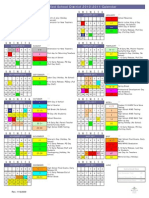

Based on Dewey's concept of interest and concern, as well as "plasticity" and "personal attitudes," a learning model (Figure 1) was developed as part of the practicum for the diploma

in teaching.

. Figure 1. The Learning Model: In the Context of the Classroom

12

CHRISTINE CHEN

The Learning Model

In the learning model (Figure 1), the heart of

the experience is the teachers' concern.

Teachers share with their practicum mentors

their concerns, observations, and reflections

of their classroom situation. The teachers,

with their mentors' guidance, design their

practicum that addresses their individual concerns. This collaborative and constructivist

planning model acts as a "powerful emotional

and intellectual process that creates learning

opportunities for teachers and their students"

(Hargreaves, Earl, Moore, & Manning, 2001,

p. 37). Such a learning experience is based on

learner-centered principles (Pierce & Kalkman, 2003) in that it emerges from the

learner's personal concern or interest. The

learner has to take into consideration his or

her professional stage (Gratz & Boulton,

1996; Katz, 1995) as well as the classroom situation, which includes students, the schedule,

the activities, and the materials, as well as the

management, policies, and philosophy that

determine what goes on in the physical space.

In this study, this learning model is used to

uncover the "practical knowledge" of teachers

and the change process so as to inform policymakers, curriculum designers, and teacher educators on educating for change.

Practical Knowledge

Elbaz (1981) conceived of the concept of

"practical knowledge" through a case study regarding a teacher who taught English literature and writing. Elbaz believes that the

teacher plays a role in "the implementation of

new curricula, adapting and changing the materials which come his or her way" (p. 43).

However, as Lortie (1969) points out, teachers

are not often viewed as possessing expertise in

experiential knowledge, and therefore their

role tends to be underrated from the perspective of the layman. The conception of teachers' "practical knowledge" emphasizes the

processes by which knowledge is being, acquired and put into practice, and is defined as

the "practically-oriented set of understandings

which they use to shape and direct the work of

teaching" (Elbaz, 1983, p. 5).

Practical knowledge is categorized under

four categories: the content, orientations,

structure, and cognitive style (Elbaz, 1981).

The content of practical knowledge refers to

the things that teachers know, such as child

development and how children learn, and

things that they know how to do, such as relating to children. However, the content of

knowledge is acquired and reenacted through

various orientations and structure.

There are five orientations of "practical

knowledge": the situational, theoretical, personal, social, and experiential. It is the interaction of these five orientations that provides

the context for learning and directs the work

of teaching. The orientations attend to the

complexity and variety of the teacher's knowledge, while the structure introduces the order

and structure in "practical knowledg6."

The structure of "practical knowledge" includes "the rule of practice," "practical principle," and "image." Elbaz (1981) elaborates that

"the rule of practice may be followed methodically, while the principle is used reflectively,

and the image guides action in an intuitive

way" (pp. 49-50).

The last category of practical knowledge is

cognitive style, which is developed as the

teacher enacts the various images of self as a

teacher. This notion of enacting teacher images prompted Clandinin (1985) to coin the

term personalpracticalknowledge. According to

Clandinin, "personal'practical knowledge is

not of knowledge which is just content nor

knowledge which is just structure" (p. 362).

Rather, it is knowledge which is "a contextually relative exercise of capacities for imaginatively ordering our experience" (Johnston,

1990, p. 467).

The above paragraphs outline the concept

of practical knowledge that acts as the conceptual framework of this study. It investigates the

process of teachers using their practical knowledge to make changes in their classrooms. This

process was initiated through the practicum

project of the in-service diploma in teaching.

Teachers as Change Agents

Methodology of the Study

As discussed, the conceptual framework of this

investigation is practical knowledge (Elbaz,

1981, 1983), which assumes a dialectic relationship between theory and practice. Teachers give shape to their knowledge in relation

to their situations and purposes, and as such, a

dynamic process develops. In order to study

this dynamic process of,leaming and change, a

qualitative approach was undertaken.

Seventeen teachers were involved in this

study. They were interviewed, their interviews

transcribed, and the observations and field

notes documented. Facts and information

from the different methods of data collection

were triangulated to seek convergence and the

data were analyzed through the lens of Elbaz's

(1983) four categories of practical knowledge.

Finally, the report of the findings was mailed

to the participants for member verification.

Profile of Participants

and Data Collection

Seventeen participants in this study were selected based on their practicum project. The

teachers who opted to make changes in the

physical design of their classroom were selected, as the changes are observable over time

and independent of settings as compared to

those who opted to work with children or staff

relations. These students were contacted and

multiple interviews took place.

The 17 participants were, graduates

(1996-1998) of the in-service diploma program in teaching. Out of the 17, 13 of them

were teachers and 4 were leaders of their early

childhood setting. They embarked on their

practicum to change the physical arrangement

of their classroom to include learning corners

and small group activities. They decided on

the change as a result of their concern over

their classroom situation. The participants described their classroom situations as being

chaotic with frequent occurrences of children

running around "doing nothing" or "doing

things to get attention."

13

I remember the moment, I gained this

knowledge in the course, I found it very

useful and I had-this motivation to want

to right away rearrange the setting.

This supports Earl and Lee's (1998) finding

that the change process typically is prompted

by the sense of urgency to make changes in the

way things are being done.

During the 2001-2002 period of investigation, observation and field notes were taken to

document evidences of learning comers and

small group activities. Participants also took

part in personal interviews, which lasted for

about an hour.

Findings

The findings reflect a change in the profile of

the participants. The 17 participants' characteristics changed from 13 teachers and 4 leaders to 5 teachers and 12 leaders. It appeared

that most of the participants made changes in

their job scope. Also, 8 of them made changes

in their job settings. For those who moved into

leadership positions, they were in the process

of helping their teachers change.

During the visits to the participants' early

childhood settings, evidences of learning corners and small group activities were observed.

Some participants were still developing their

learning comers, while others had learning

comers inside or outside the classrooms. There

was also evidence of small group learning at

different tables, and children were learning on

the floor while others worked at the tables.

It was clear that all 17 participants were

able to sustain the change in one form or other

and that these teachers acted as change

agents. Therefore, a closer look at their "practical knowledge" can uncover the conditions

that promote change. Their practical knowledge is presented in four categories: content,

orientations, structure, and cognitive style.

The Content of Practical Knowledge

In terms of content, the participants appear to

have a good grounding in child development.

14

CHRISTINE CHEN

"You really need to know how children develop before you can plan a curriculum for

them." This knowledge in child development

seemed to guide them in planning and managing the early childhood curriculum.

Besides child development, participants

also had a good understanding of early childhood curriculum. According to the participants, the curriculum is a "framework" that

"guides children through the different development" stages, and it is not "fixed" as "it

should basically be based on ability and also

the kind of children that we have at the particular year." Therefore, with knowledge in

child development and early childhood curriculum, the participants felt empowered to

make necessary changes.

Orientations of Practical Knowledge

very active, it is kind of boring to always

sit in front of the white board.... I have

learnt that there are a lot of advantages

learning through play. I believe that children know what they want to learn....

Even though the curriculum is set, I don't

really follow it.

Third, the optimism of the participants

further promoted change:

I think they will change.... You see right

now, I have about 50% of staff doing the

small group learning .... They are trying

their best actually and I can see that. So

I'm afraid I need some time, and if this

50% of them are doing it then the other

50% will be influenced sooner or later...

based on trial and error.. . try to use different ways to teach them [children] and

then you notice that this is the best way.

Orientations of "practical knowledge" included five subcategories: situational, social,

personal, theoretical, and experiential orientation. First, the participants in this study

worked in social environments in which autonomy is encouraged. One of the leader participants described the autonomy she accorded

to her teachers:

It appears that both the optimistic disposition and the willingness to learn new ways

have resulted in the implementation of

Basically, they have a free hand. I just give

them the guideline of what the kids need

to know and they will plan according to

what they feel the kids can learn from

their planning... because in the diploma

course, I understand that the teacher is

the one who knows what is best for their

children.

same wavelength, thinking [along] the

same wavelength, so it makes things easier.

Second, these teachers had personal orientations in the form of beliefs and preferences that determine how they taught children.

I believe that children at this very young

age, they actually learn through lots of

hands-on, lots of interacting with their

environment, their peers .... I prefer to

learn things through activities and

through experiences rather than through

theories all the time. So, I would understand children, being children, are usually

change. But credit is also given to support rendered by the participants' network of professional colleagues.

One of my teachers, she did the same

diploma with me. So I have people on the

It is important to have a supportive network of teachers (Fullan & Hargreaves, 1996;

Hargreaves, 1994; McLaughlin & Talbert,

1993; Nias, Southworth, & Yeomans, 1989)

who have the same knowledge and under-

standing of early childhood curriculum to implement the necessary changes (Newmann &

Wehlage, 1995; Rosenholtz, 1989) in early

childhood classrooms.

Finally, in terms of the theoretical orientation, it was found that theory, to most participants, is not concrete. Many had difficulties in

defining theory: "I am not very sure how to put

it into words." Few participants were able to

identify Piaget's and Erikson's theories as being

useful. Most participants were skeptical about

the usefulness of theories. One participant remarked, "Theories are dead. Practice is alive."

Teachers as Change Agents

Thus, it revealed that the participants believed that they relied very little on their "theoretical" orientation while implementing

changes.

Structure of Practical Knowledge

The third category of "practical knowledge" is

structure. The structure of practical knowledge refers to the principles and rules of practice held by teachers:

The first guiding principle is responsibility. A person has to be responsible for

everything we do. So this is very important and I stress it to the teachers.

Respect, in tenris of basic manners. I

want them to show respect to their parents ... like greeting, saying thank you,

please. I think these are basic manners

they should have.

Children are very unique, very individual-so we the teachers are supposed

to guide them through and help them in

the different development.

They have to keep their toys after

playing and they have to share.

Thus, it appears that responsibility and respect are the main principles: respecting the

child's uniqueness and the responsibility for

the child's holistic development. These principles set the tone for classroom management.

The children were expected to respect others

by not screaming but speaking one at a time

and being responsible for sharing and cleaning

up after themselves. These principles and rules

guide teacher behavior and a teacher image is

formed. Consequently, teachers enact the images they have of themselves and. develop

their cognitive style.

Cognitive Style of

Practical Knowledge

The fourth category of practical knowledge is

cognitive style. Cognitive style is expressed in

terms of teacher images (Clandinin, 1985;

Johnston, 1990) of themselves as teachers and

as leaders in their early childhood settings.

Participants described themselves as "creators

15

1

of opportunities," models, and good classroom

managers. The other images are presented in

the following statements:

"*A nurturer with love and care for children: "love and care for the childrenthat is my commitment to teaching."

"*A fun-loVing teacher: "As a teacher, I

think I should be fun loving because I

like to do fun things with,the children."

""An "octopus": "At the moment, I am a

bit-rather like an octopus actually,

like trying to do everything at one time,

and I have to change everything, because now 1 am having this new learning."

"*A facilitator: "I was a facilitator, rather

than a teacher. I mean in the local context, we always see ourselves,, as a

teacher, you must always teach, teach.

But at that time, I -was really facilitating, because the children were really

learning on their own."

The findings as presented have unveiled

the practical knowledge of the 17 participants

who acted as change agents. It is evident that

their practical knowledge consists of a solid

foundation in child development with a good

understanding of the early childhood curriculum. They work in an autonomous social environment with optimistic dispositions and personal beliefs that promote change. Their

principles and rules revolve around respect

and responsibility and their cognitive style reflects their commitment to teaching in terms

of being a model, creator of opportunities,

good classroom manager, nurturer, fun-loving

teacher, octopus, and facilitator.

How Teachers

Implemented the Change

The participants approached change in different ways. One participant reported that she

started by observing results. According to Fullan (1991), teachers need to be able to see

how change benefits their students.

16

CHRISTINE CHEN

I think what I did was, before I changed, I

made observations, and I recorded, like

the number of conflicts in certain places.

After I did the changes, I did the same

recording, and I can quantify the benefitseven the improvement. So I learnt that I

can really see the difference.

Another participant reported that she

started the change when she became the principal of the preschool.

Since I took over as principal, I have been

encouraging the teachers to conduct small

group activities. Like during staff meetings, I would encourage, I would first

praise the teachers for consistently doing

small group activities. From the encouragement, hopefully others would catch

on. It is not easy I would say to have small

group activities. They need a lot of

praises, a lot of encouragement. I think

encouragement for the teachers is very

important.

Another way of approaching change was

through approaching the principal and then

working with the teachers.

I spoke to the principal and then I started

it in my classroom first. And then slowly

try to influence my neighbor, which I took

quite a long time to convince her. And after convincing her, I approached the

Kindergarten 1 teacher next to me. Then

the Nursery teachers thought that it was

going on very well, so they approached me

and then we discussed and shared with

them my experience. The following year,

when I was in Kindergarten 2, I managed

to try to influence the Kindergarten 2

teacher who is more senior than me. Yes it

is quite difficult to influence those more

senior, but finally she got the picture and

the whole school got going.

Yet another approach was working with

the parents and having the parents convince

the management:

I called the parents in. I had a meeting

with the parents. I went to research into

the good things about learning corners. I

showed the parents the learning corners.

And I showed them how these learning

comers will enhance the children's development. The listening comer will enhance their oratory and their speech. I informed them that they would not be at

the comers every day. They would be at

the comers only after they have finished

their core subject. If they finish fast, then

only do they go into the learning comers.

It was difficult. It took me at least three

months to convince the parents that

learning comers are good. When we did a

project on learning comers I roped them

in. Then they realized these learning corners do benefit the children. Whenever I

wanted to make a new corner, I ask them,

"What do you think the children can

learn best at this art and craft comer?

What materials should they put in?...

And even for the maths comer, I ask some

of the parents to bring in materials. I invited them in to observe at the comer. I

invited a few of them per day to show

them how I teach and how the comers are

being used by the children. When the

children got to Kindergarten 2, 1 continued with dte learning comers again and

only then did the parents see the difference in the children. So all in all it took

them two years to see results.

When the children left the center, the

teacher requested the parents to write to the

management about the learning center concept. "Eighteen of them, all gave very positive

feedback, and that was 100% of the parents!"

This participant implemented change by using

her knowledge on learning comers to educate

her students and involved the parents in the

change process. Others used their skills in observation or worked with teachers and principals to implement changes.

Summary, Implications,

and Recommendations

It is clear that the process of change started

when the participants observed that things

were not happening the way they would like

for their children. The participants in this

Teachers as Change Agents

study are change agents who changed their

own classroom teaching practice, influenced

other teachers to change, and convinced parents and management that change is beneficial for children. They were able to implement

effective change through using their knowledge of child development and the early

childhood curriculum. They also used their

strong personal orientation of being passionate

in their beliefs about how children learn and

were proactive learners who held optimistic

views about learning and change. They were

autonomous. professionals who work in environments that promote autonomy, and, if they

were not in an autonomous environment, they

created one by working with management to

provide the autonomy for themselves and for

their teachers.

Therefore, this study presents the image of

the teacher as an active agent of change. This

image validates Dewey's assertion of teachers

as thinking and acting in the world and Elbaz's

assumption that teachers possess "practical

knowledge" that "shape and directs the work

of teaching" (Elbaz, 1983, p. 5) in terms of

having the "valuable resources which enable

her to take an active role in shaping her environment and determining the style and ends

of her work" (p. 6).

I believe in myself, that I can do lots of

things. Sometimes, it might not be easy,

in the process, because you might not

have the support that you need from people. But ultimately, I think you can do as

much as you can, so then, slowly, they

will be able to see that whatever you did,

it does work, and then, hopefully, they

will follow.

This statement implies that change is brought

about through working with others. As discussed, these teachers worked with other

teachers, principals, management, and parents. Since the change process is about working with adults, it is important that in educating teachers for change, teacher education

programs should include knowledge and skills

that help teachers feel competent in working

with parents, management, and other teach-

17

ers. Perhaps a c6urse in change management

would be useful in facilitating educational

change.

Another area of focus is ensuring that

teachers have the necessary content that supports a strong foundation in child development and early childhood curriculum. However, since reservations have been expressed

on the usefulness of theories, caution isneeded

in delivering theories. Theories should be

taught in context, together with lots of practical applications and examples, to make the

necessary linkage between theory and 'practice. One way of relating theory to practice is

by using videos and demonstration classrooms

with one-way mirrors. A number of participants shared that videos and visits to settings

with learning comers and learning in small

groups helped them to visualize the change.

It was so fantastic, you see kids ... they

are so interested in what they are doing.

They are actually doing unconscious

learning while they are in the corners and

they are independent learners.

It is in visualizing the change that teachers create "a vision of the desired teacher role"

(Bullough, 1992, p. 240). Also, since the

change process was ignited by the learnercentered practicum based on observations, reflections, and contextualization of concerns,

with the guidance of a practicum mentor, such

a learning model can be replicated to promote.

learning and change. Attention can also be

given to helping teachers become aware of

their orientations in "practical knowledge"

and the structure and cognitive styles that

guide their practice.

In addition, teachers have also acknowledged the supportive role of their professional

network in supporting them through change.

As such, it is recommended that teachers be

encouraged to network and form learning

communities. According to P6uravood

(1997), learning communities assist teachers

to change in a complex world, and Hoban

(2002) states, "Teacher networks enable the

participants to negotiateknowledge according

to their unique contexts" (p. 43). Therefore, it

18

CHRISTINE CHEN

is suggested that teacher education classrooms

include learning in small groups to facilitate

the development of learning communities.

Conclusion

It is evident that the teachers in this study

acted as change agents and apparently change

was ignited through reflecting on concerns.

Therefore, it appears that the learning model

(Figure 1) adopted in the practicum was instrumental to the change process. The learning model was effective because it was conceived based on values of concern and a

nurturing mentoring relationship. Hofstede's

(1997) and Chen's (2000) studies have reported that the culture in Singapore is high on

the femininity dimension. Hence, using a

model appropriate to the culture seemed to

have unleashed the dynamism and plasticity

(Dewey, 1916/1997) of the teachers and empowered them to apply their "practical knowledge" (Elbaz, 1981, 1983) and become "creators of opportunities."

As such, the challenge for teacher educators is to understand the culture that our students are coming from and to apply our "practical knowledge" to design and create learning

opportunities. By taking up this challenge, we

become the starting point of the change

process and, like our students, become change

agents ourselves.IM

References

Bullough, R. (1992). Beginning teacher curriculum

decision

making,

personal

teaching

metaphors, and teacher education. Teaching

and Teacher Education, 8(3), 239-252.

Chen, C. (2000). Formal mentoring relationships of

SingaporeanChinese in two organizations in Singapore. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, George

Washington University, Washington, DC.

Clandinin, D. J. (1985). Personal practical knowledge: A study of teachers' classroom images.

Curriculum Inquiry, 15(4), 361-385.

Dewey, J. (1916/1997). Democracy and education.

New York: Free Press.

Dewey, J. (1933). How we think. New York: D. C.

Heath.

Earl, L., & Lee, L. L. (1998). Evaluation of the Manitoba School Improvement Program. Toronto: International Center for Educational Change at

OISE/UT.

Elbaz, F (1981). The teacher's "practical knowledge": A report of a case study. Curriculum Inquiry, 1](1), 43-71.

Elbaz, E (1983). Teacher thinking: A study of practical knowledge. London: Croom Helm.

Fullan, M. (1991). The meaning of educational

change. New York: Teachers College Press.

Fullan, M., & Hargreaves, A. (1996). What's worth

fighting for in your school? (2nd ed.). New York:

Teachers College Press.

Gratz, R., & Boulton, P. (1996). Erikson and early

childhood educators: Looking at ourselves and

our profession developmentally. Young Children, 51(5), 74-78.

Hargreaves, A. (1994). Changing teachers, changing

times: Teachers' work and culture in the postmodem age. New York: Teachers College Press.

Hargreaves, A., Earl, L., Moore, S., & Manning, S.

(2001). Learning to change. San Francisco:

Jossey-Bass.

Hoban, G. E (2002). Teacher learningfor educational

change. Buckingham, UK: Open University

Press.

Hofstede, 0. (1997). Cultures and organizations:

Software of the mind. London: McGraw-Hill.

Johnston, S. (1990). Understanding curriculum decision-making through teacher images. Journal

of Curriculum Studies, 22(5), 463-471.

Katz, L. (1995). Talks with teachers of young children.

New Jersey: Alex Publishing.

Lane, S., Lacefield-Parachini, N., & Isken, J.

(2003). Developing Novice teachers as change

agents: Student teacher placements "against

the grain." Teacher Education Quarterly, 50,

55-68.

Lortie, D. C. (1969). The balance of control and

autonomy in elementary school teaching.

In A. Etzioni (Ed.), The semi-professions

and their organizations. New York: Free

Press.

McLaughlin, M., & Talbert, J. (1993). Contexts

that matter for teaching and learning. Stanford,

CA: Center for Research on the Context of

Secondary School Teachers.

Newmann, F, & Wehlarge, G. (1995). Successful

school restructuring. Madison, WI: Center on

Organization and Restructuring Schools.

Teachers as Change Agents

Nias, J., Southworth, G., & Yeomans, A. (1989).

Staff relationshipsin the primary school. London:

Cassell.

Pierce, J. W., & Kalkman, D. L. (2003). Applying

learner-centered principles in teacher education. Theory Into Practice, 24(2), 127-132.

Pouravood, R. G. (1997). Chaos, complexity and

learning community: What do they mean for

education? School Community Journal, 7(2),

57-64.

19

Rosenholtz, S. (1989). Teachers' workplace. New

York: Longman.

4*.

-*e.*

Christine Chen is the founder and president

of the Association for Early Childhood Education in Singapore. Her research interests include teacher development and learning,

mentoring relationships, and leadership.

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

TITLE: Teachers as Change Agents: A Study of In-Service

Teachers Practical Knowledge

SOURCE: Action Teach Educ 26 no4 Wint 2005

WN: 0534904813002

The magazine publisher is the copyright holder of this article and it

is reproduced with permission. Further reproduction of this article in

violation of the copyright is prohibited. To contact the publisher:

http://www.siu.edu/departments/coe/ate/

Copyright 1982-2005 The H.W. Wilson Company.

All rights reserved.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Swing ThoughtsDocumento9 pagineSwing Thoughtsodic200250% (2)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Word Practice For SoundsDocumento18 pagineWord Practice For SoundsHidayah RosleeNessuna valutazione finora

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- What Is Student Agency and Should We Care?Documento3 pagineWhat Is Student Agency and Should We Care?Hande ÖzkeskinNessuna valutazione finora

- Chinese Students IELTS WritingDocumento37 pagineChinese Students IELTS Writinggeroniml100% (1)

- The Oliva ModelDocumento1 paginaThe Oliva Modellailazk50% (2)

- Models of TeachingDocumento60 pagineModels of TeachingHidayah Roslee100% (2)

- Management Trainee Application Form Updatedtcm 75270164Documento8 pagineManagement Trainee Application Form Updatedtcm 75270164dilpanaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Peacock and The Crow PDFDocumento3 pagineThe Peacock and The Crow PDFHidayah Roslee100% (1)

- Riddle Time Q and ADocumento2 pagineRiddle Time Q and AHidayah RosleeNessuna valutazione finora

- Positive Vs Negative ReinforcementDocumento3 paginePositive Vs Negative ReinforcementHidayah Roslee100% (1)

- Ngoc Thach Phan Thesis VietnamDocumento381 pagineNgoc Thach Phan Thesis VietnamRené PedrozaNessuna valutazione finora

- English Fun RiddlesDocumento3 pagineEnglish Fun RiddlesHidayah RosleeNessuna valutazione finora

- Toeic ListeningDocumento11 pagineToeic ListeningMartinArciniegaNessuna valutazione finora

- Factors To Choose A StrategyDocumento8 pagineFactors To Choose A StrategySiti Azhani Abu BakarNessuna valutazione finora

- Fall in Love With The Real ThingDocumento4 pagineFall in Love With The Real ThingHidayah Roslee100% (1)

- Popular Topics For Interview SPPDocumento1 paginaPopular Topics For Interview SPPHidayah RosleeNessuna valutazione finora

- Phonics First White PapersDocumento13 paginePhonics First White PapersHidayah RosleeNessuna valutazione finora

- Student Engagement in T&LDocumento59 pagineStudent Engagement in T&LHidayah RosleeNessuna valutazione finora

- Format of Practicum Weekly JournalsDocumento2 pagineFormat of Practicum Weekly JournalsHidayah RosleeNessuna valutazione finora

- Sample Academic Interview QuestionsDocumento5 pagineSample Academic Interview QuestionsHidayah RosleeNessuna valutazione finora

- SJK (C) - Year Three English Language Semester Test 1 201 - Time: 60 MinutesDocumento8 pagineSJK (C) - Year Three English Language Semester Test 1 201 - Time: 60 MinutesMohammad ZulkiflieNessuna valutazione finora

- Gwendolyn The Gorgeous Witch: by Nor Hidayah BT RosleeDocumento17 pagineGwendolyn The Gorgeous Witch: by Nor Hidayah BT RosleeHidayah RosleeNessuna valutazione finora

- Use of WH-Questions in Skimming and ScanningDocumento10 pagineUse of WH-Questions in Skimming and ScanningHidayah RosleeNessuna valutazione finora

- English Year 3 Lesson Plan: Complete Texts With The Missing Word, Phrase or SentenceDocumento4 pagineEnglish Year 3 Lesson Plan: Complete Texts With The Missing Word, Phrase or SentenceNor HidayahNessuna valutazione finora

- Learner and Learning Environment (Compare and Contrast Watson, Pavlov, Thorndike, Skinner)Documento10 pagineLearner and Learning Environment (Compare and Contrast Watson, Pavlov, Thorndike, Skinner)Hidayah Roslee0% (1)

- Activities For ChildrenDocumento4 pagineActivities For ChildrenHidayah RosleeNessuna valutazione finora

- Use of WH-Questions in Skimming and ScanningDocumento10 pagineUse of WH-Questions in Skimming and ScanningHidayah RosleeNessuna valutazione finora

- IGCSE Mathematics 2016 SyllabusDocumento39 pagineIGCSE Mathematics 2016 SyllabusZahir Sher0% (1)

- Animal Needs Lesson PlanDocumento4 pagineAnimal Needs Lesson Planapi-279301695Nessuna valutazione finora

- Edu 532 ReviewerDocumento4 pagineEdu 532 ReviewerLabs YuuuNessuna valutazione finora

- Summary of The Project: To Show The Different Stages of The Project Implementation A. Pre-PlanningDocumento7 pagineSummary of The Project: To Show The Different Stages of The Project Implementation A. Pre-PlanningAntonio B ManaoisNessuna valutazione finora

- Writing Skill Lesson Plan For Year 3 Topic Having FunDocumento6 pagineWriting Skill Lesson Plan For Year 3 Topic Having Funnoorizah92Nessuna valutazione finora

- Everyday Dialogues at The Box Office FiletypepdfDocumento2 pagineEveryday Dialogues at The Box Office FiletypepdfBrendaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lexical Exploitation of TextsDocumento3 pagineLexical Exploitation of TextsZulfiqar AhmadNessuna valutazione finora

- Reseach KoDocumento21 pagineReseach KoAngeloNessuna valutazione finora

- Syllabus English - Grade 3 RicaDocumento5 pagineSyllabus English - Grade 3 RicaRicaSanJose100% (1)

- Fransiskus Daud Try Surya A Bahasa Inggris PTK PPG DALJAB 2Documento47 pagineFransiskus Daud Try Surya A Bahasa Inggris PTK PPG DALJAB 2Pank INessuna valutazione finora

- Division With Remainders Lesson PlanDocumento3 pagineDivision With Remainders Lesson Planapi-237235020Nessuna valutazione finora

- Getting in An Applicant S Guide To Graduate SchoolDocumento14 pagineGetting in An Applicant S Guide To Graduate SchoolliphaellNessuna valutazione finora

- Construction Technology On SKYPARKDocumento17 pagineConstruction Technology On SKYPARKDarrenTofuNessuna valutazione finora

- Needs Analysis Questionnaire For EnglishDocumento10 pagineNeeds Analysis Questionnaire For EnglishRosee LikeblueNessuna valutazione finora

- Analyze The Problems Faced by Primary School Teachers of Booni (Chitral) (Saira Gul)Documento64 pagineAnalyze The Problems Faced by Primary School Teachers of Booni (Chitral) (Saira Gul)Muhammad Nawaz Khan Abbasi50% (6)

- Higley 2010-2011 District CalendarDocumento1 paginaHigley 2010-2011 District CalendarMelissaNewmanMinsonNessuna valutazione finora

- Avalon School Annual Report 2014-2015Documento88 pagineAvalon School Annual Report 2014-2015Tim Quealy0% (1)

- Julia Giordano Resume May 2Documento2 pagineJulia Giordano Resume May 2api-253760877Nessuna valutazione finora

- MCR3U Unit 2 PlanDocumento1 paginaMCR3U Unit 2 PlanSathya NamaliNessuna valutazione finora

- RoblesDocumento4 pagineRoblesapi-447548045Nessuna valutazione finora

- Camilla Justice BrochureDocumento2 pagineCamilla Justice Brochurecjustice1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Varsity Model Presentation - KH 2130Documento10 pagineVarsity Model Presentation - KH 2130api-260132958Nessuna valutazione finora