Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Adult Onset Family History - 2002

Caricato da

Rafael IribarrenCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Adult Onset Family History - 2002

Caricato da

Rafael IribarrenCopyright:

Formati disponibili

This article was downloaded by:[informa internal users]

[informa internal users]

On: 5 July 2007

Access Details: [subscription number 755239602]

Publisher: Informa Healthcare

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954

Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Current Eye Research

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:

http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713618400

Family history and reading habits in adult-onset myopia

Rafael Iribarren; Guillermo Iribarren; Maria M. Castagnola; Alejandra Balsa; Mario

R. Cerrella; Alejandro Armesto; Andrea Fornaciari; Toms Pfrtner

First Published on: 01 November 2002

To cite this Article: Iribarren, Rafael, Iribarren, Guillermo, Castagnola, Maria M.,

Balsa, Alejandra, Cerrella, Mario R., Armesto, Alejandro, Fornaciari, Andrea and

Pfrtner, Toms , (2002) 'Family history and reading habits in adult-onset myopia',

Current Eye Research, 25:5, 309 - 315

To link to this article: DOI: 10.1076/ceyr.25.5.309.13494

URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1076/ceyr.25.5.309.13494

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article maybe used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction,

re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly

forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be

complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be

independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings,

demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or

arising out of the use of this material.

Taylor and Francis 2007

Downloaded By: [informa internal users] At: 16:02 5 July 2007

Current Eye Research

2002, Vol. 25, No. 5, pp. 309315

0271-3683/02/2505-309$16.00

Swets & Zeitlinger

Family history and reading habits in adult-onset myopia

Rafael Iribarren1, Guillermo Iribarren1, Maria M. Castagnola1, Alejandra Balsa1, Mario R. Cerrella1, Alejandro Armesto1,

Andrea Fornaciari2 and Toms Pfrtner 3

Depto. de Oftalmologa, Centro Mdico San Luis, Buenos Aires; 2Facultad de Ciencias Jurdicas, Universidad del Salvador,

Buenos Aires; 3Laboratorio Pfrtner-Cornealent, Buenos Aires, Argentina

1

Abstract

Purpose. A retrospective study was developed to evaluate

risk factors in adult-onset myopia.

Methods. Subjects included were 25 to 35 years old. There

were 116 non-myopic subjects in the control group and 66

myopic subjects with first lens prescription at age 17 or later.

Subjects received a questionnaire about academic achievement, daily hours of reading during years of study, and family

history of myopia.

Results. The level of academic achievement was similar for

myopic and non-myopic groups in this sample. Myopia was

associated with family history (c2 = 6.131, p 0.013) and

with daily hours of reading during years of study (c2 = 3.904,

p 0.048). According to multiple logistic regression analysis, the correlation of myopia with family history adjusted

for daily hours of reading remained significant (p 0.005),

whereas the correlation with daily hours of reading adjusted

for family history was not significant (p 0.061).

Conclusions. After multivariate analysis, adult-onset myopia

was significantly associated only with family history of

myopia.

Keywords: adult-myopia; family history; nearwork

Introduction

Many papers have been published18 regarding prevalence,

evolution and risk factors of myopia development in children

and teenagers, because affected young people can be easily

located and followed through the years. Those studies have

clearly shown that myopia prevalence increases during child-

hood,24 and that family history5,79 and near-work5,7,1015 are

risk factors associated with myopia development. It has

also been reported that myopia prevalence is greater in

the city than in the countryside24,16,17 and that myopia is

associated with high family income and higher academic

achievement.1825

Population studies2531 have showed that myopia prevalence increases with age as new cases are developed, reaching a maximum in young adulthood. Recent work in Norway

by Kinge et al.,3233 and in Denmark by Fledelius26,34 clearly

showed the development of many new cases of myopia after

18 years of age. These new, adult-onset cases could account

for 50% of the prevalence in adulthood. Parssinenn in

Finland35 and Midelfart et al. in Norway36 obtained similar

data. Biometric studies32,3742 have shown that adult-onset

myopia is associated with increased axial length like youth

onset myopia. At least some of adult-onset myopes could

continue increasing refractive error in their late thirties.43

Recent studies have shown that myopia in adults increases

in association with intense nearwork.3233,42 On the other

hand, Bullimore et al.44 did not find any association of

myopia progression with near-work in a group of adult

contact lens users. No studies could be found concerning

family history in this type of myopia. The present retrospective study was developed to evaluate family history of

myopia and the amount of reading hours in subjects with

adult onset myopia.

Materials and methods

As recommended by Grosvenor45 we divide myopes into

youth-onset and adult-onset according to the age at which

Received: July 15, 2002

Accepted: November 20, 2002

Correspondence: Rafael Iribarren, Depto. de Oftalmologa, Centro Mdico San Luis, San Martn de Tours 2980, (1425) Buenos Aires,

Argentina. Tel/Fax: 54-11-4801-8050, E-mail: rafael@ar.inter.net

Downloaded By: [informa internal users] At: 16:02 5 July 2007

310

R. Iribarren et al.

their symptoms begin. This study was conducted in a

Caucasian population of diverse national origins, resident in

Buenos Aires, Argentina. These subjects of both sexes are

participants in prepaid health-care plans and belong to

a well-educated social class having high and medium

family incomes. We followed the tenets of the Declaration of

Helsinki. Subjects for the study were every consecutive

patient between 25 and 35 years of age who came for vision

examination in an ophthalmologists office from July to

November 2001, minus exclusions as detailed below. The

same five ophthalmologists performed all the ophthalmic

examinations. All subjects gave informed consent for the

investigation. They first received a questionnaire with the following questions: 1) How many years have you spent studying at University (after High School)?, 2) How many hours

a day, on average, did you spend reading in those study

years?. Then, myopia was defined with an indirect statement, as the need of lenses for far distance at a young age.

Finally, questions 3) and 4) queried whether father and

mother were myopic (possible answers were yes, no

or dont know). For testing the reliability of these last

two questions, a similar questionnaire was administered to

another group of 59 consecutive subjects who bought contact

lenses at an opticians shop. With the same definition of

myopia, this time we queried each subject whether he was

myopic, with the same three possible answers. Then, the lens

prescription (spherical equivalent) was registered, and thus

the accuracy of the responses was checked.

After each subject answered the four questions, the ophthalmologist (AA, AB, MC, MMC, RI), blind to the answers,

performed the ophthalmic examination. If the patient already

used lenses, a lensometer (Topcon) was used to measure

them for comparison with the actual refraction. Visual acuity

(VA) was obtained using projected Snellen optotypes at 3

meters distance (Topcon). If the patient did not have any previous correction, and reached a VA of 20/25 or better with

either eye, the examiner performed a fogging technique with

a +1 diopter lens to find latent hyperopia. If the patient then

perceived a slight blur in the 20/25 letters he was classified

in the control group; on the other hand, if he did not perceive

blur under fogging or said that he saw better, he was not

included in the study. Patients who were already using positive lenses for reading at this young age were considered

hyperopic and were not included. Also excluded were subjects with astigmatism greater than one diopter, those with

anisometropia greater than one diopter, those who presented

any form of strabismus, and those with best corrected VA

lower than 20/25 in either eye.

If the subject was myopic or could not see the 20/25 VA

line with either uncorrected eye, the examiner used the usual

subjective method to assess distance refractive state, with

trial frame, prescribing the least negative correction necessary to obtain 20/25 visual acuity in each eye. Myopia was

defined as having a myopic error of at least -0.75 diopters

(spherical equivalent) in either eye. The examiner asked the

myopic subjects at what age had they begun using lenses for

far distance. Adult-onset myopia was considered as the one

with onset at age 17 years or later, so 26 myopic subjects who

had their first prescription before age 17 years were excluded.

Thus, 116 subjects remained in the control group and 66

subjects in the myopic group. There were 78 females and

104 males. Both groups were matched by sex (c2 = 0.42,

p 0.52) and age (t-student test, p 0.66).

Regarding family history, subjects were considered positive if they answered that they had either one or two myopic

parents, subjects who answered no with regard to both

parents were considered negative, and subjects who answered

dont know with regard to both parents were considered

dont know responses as well as the ones who answered

no for one parent and dont know for the other.

The myopic and control groups were compared with

respect to family history, hours of reading and years of study.

As presence or absence of myopia is a dichotomous variable,

the continuous exposure variables (hours of reading and

years of study) were converted into dichotomous variables

(i.e., values above or below the median) to perform Chisquare univariate analysis. Then, multivariate analysis (logistic regression) was performed for the significant variables.

The median values for the sample were 6 years of study and

4 hours a day spent reading.

Results

There were 5 hyperopes and 54 myopes in the group of 59

contact lens buyers used for validating the family history

questionnaire. There were no dont know responses to

the question whether they were myopic or not. The myopes

reported their myopic condition accurately after reading our

definition of myopia, because we confirmed the presence of

myopic refractions in 53 out of 54 of them. The 5 hyperopes

were also accurate, as they all answered they were not myopic.

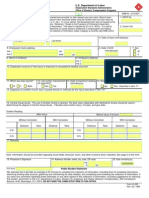

The mean age of onset of myopia for subjects in this study

(n = 66) was 22.06 4.15 years. Figure 1 displays the frequency of each age of myopia onset. The median refractive

error for the myopic group was -1.75 diopters for the right

eye (Fig. 2, range from -0.75 to -5.50). Table 1 shows the

results of univariate analysis. Myopia was found to be associated significantly with family history and with the number

of daily hours of reading, but the years of study were similar

in both groups (Fig. 3).

Regarding the question about family history, the incidence

of dont know responses was low: 18.1% in the control

group, and 4.55% in the myopic group (Fig. 4). The rate

of dont know responses was 11.3% for the whole

sample. A positive family history was present in 50% of the

myopic subjects in contrast with 26.72% of the control group

(Fig. 4).

The myopic group recalled, on average, almost one more

daily hour of reading than the control group (Fig. 5). As

myopia was found to be associated significantly with family

history and hours of reading, multiple logistic regression

Years of Study

Number of subjects

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

311

8.11

7.91

5.72

5.68

3.34

3.45

Controls

Myopes

Age of first lens prescription

Figure 1. Number of subjects for each reported age of first lens

prescription, in years.

35

Figure 3. Average number of years of University study for both

myopic and control groups (standard deviations are represented by

the vertical bars).

100%

30

Number of Subjects

Downloaded By: [informa internal users] At: 16:02 5 July 2007

Family history and reading habits in adult-onset myopia

80%

no family history

25

60%

20

15

40%

10

20%

0%

with family

history

'don't know'

response

controls

0

-4.75 to - -3.75 to - -2.75 to - -1.75 to - -0.75 to 5.5

4.5

3.5

2.5

1.50

Diopters of Spherical Equivalent (right eye)

Figure 2. Number of subjects for each refractive interval in

diopters (myopic group only).

myopes

Figure 4. Percentage of subjects with no family history of myopia

in white, and with at least one myopic parent in gray, for both

myopic and control groups (note the small rate of dont know

responses).

Table 1.

Univariate analysis

Family history vs. myopia

Daily hours of reading

vs. myopia

Years of study vs. myopia

c2

p-value

6.131

3.904

0.013

0.048

Significant

Significant

0.211

0.646

Not significant

analysis was performed. Table 2 shows that family history

adjusted for daily hours of reading remained significant, but

daily hours of reading adjusted for family history, lost significance. Therefore, the most important finding in this study

is a significant association of adult onset myopia with family

history of myopia.

Discussion

The people enrolled for this retrospective study came to a

general Ophthalmologic practice office with vision-related

Figure 5. Average number of reading hours during the study years

for both myopic and control groups (standard deviations are represented by the vertical bars).

symptoms such as headaches, for vision screening or lens

prescription. Most of our patients are older than 40 years of

age, with presbyopia and cataract as their main problems. It

took five months to gather this group of consecutive young

subjects among our patients. In Buenos Aires city, schoolaged children with refractive errors usually go to pediatric

Downloaded By: [informa internal users] At: 16:02 5 July 2007

312

R. Iribarren et al.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis

Family history adjusted for

daily hours of reading

Daily hours of reading adjusted

for family history

Odds-ratio

95% CI

p-value*

2368

(2.14.6)

0.005

Significant

1692

(0.93.23)

0.061

Not significant

* p-value obtained from multiple logistic regression.

ophthalmologists and remain with them as they grow older,

whereas adult-onset myopes usually go to general ophthalmologists when they need lens prescription. This may be the

reason why we found more adult-onset myopes than earlyonset myopes in our sampling.

Fledelius has shown that myopes remember accurately the

age of their first lens prescription.46 It is possible that we

found a high incidence of adult myopia because of delayed

reporting of lens prescription in subjects who develop

myopia slowly and begin lens use after a year or two of symptoms onset. The fact that some myopes in this sample had a

mean spherical equivalent greater than -3.75, and therefore

could be youth-onset myopes who had remained uncorrected

until they were adults, would be consistent with this possibility. However, some adult onset myopes can develop great

amounts of myopia, as indicated by the three subjects with

adult-onset myopia of more than -9 diopters included in the

study of Fedelius.46 In fact, the 10 most myopic subjects in

the present study had an average onset age of 19.7 years and

were 29.7 years old on average when interviewed. They could

easily have developed 4 diopters of myopia in ten years, at a

rate less than -0.50 diopters a year.

The sample has a high level of education (on average 6

years of study at the University). Since many epidemiological studies1825 have shown a higher prevalence of myopia

among well-educated people, we expected to confirm this in

our study, but no significant difference in years of study was

found between the two groups. This can be due to the fact

that the sample belongs to a high-income well-educated

population and not a general one, where one would expect

different levels of education. However, there was a significant difference in the amount of daily hours of reading

during University time: myopes read for more time than

non-myopes. This has been found previously in myopic

children7,11,1314 and military conscripts.5

Retrospective questionnaires are not very reliable because

of recall bias. But the subjects in this study were 25 to 35

years old, so they could remember easily what had happened

during their recent study years. The number of University

study years can be considered a reliable answer. On the contrary, the question about the average number of daily hours

of reading in study years, is likely to be a major source of

bias in this study. Subjects may blame their myopia on near

work, and this could lead to bias in the retrospective report-

ing of near-work habits. To avoid this type of bias, Rah

et al.47 have initiated a prospective study with objective

measurement of near-work activity.

Although students may spend significant time at near

work other than reading, this was the only near-work

task measured in the present study because previous

studies7,34 have showed that reading was the principal

near-work activity associated with myopic progression in

students.

The question about family history of myopia was performed in as reliable a manner as possible: by asking about

myopia after defining it as the need of lenses for far distance at a young age. This kind of question usually has

low rate of dont know response, as shown in a previous

study (8.9%)48 as well as the present one (11.3%). In the

non-myopic group there was a higher rate of dont know

answers, perhaps because these subjects, who were not using

lenses, may not have understood their parents ametropias

(Fig. 4). The fact that most contact lens buyers correctly identified their myopic condition, further confirms the reliability

of reporting of family history by myopes in our population.

It is also possible that our subjects sometimes classified high

hyperopic parents as myopes, simply because they wore corrective lenses of some kind. This last type of bias should be

small, because the prevalence of high hyperopia is very low

(for example, <10% in 15 year-old children in Chile,4 with a

population similar to ours).

Another possible bias against finding an association of

myopia with reading habits in this study, is the fact that in

11 out of the 66 myopes the age of onset was older than 25

years, after the usual period of University study. Subjects in

this group had studied on average 6 years, and their myopia

did not begin until after their years of study had ended.

Besides, some of the youngest subjects in the control group

(now classified as non-myopes) could become myopic in

the near future as a result of genetic or environmental risk

factors. However, as Figure 1 shows, most subjects had

their myopia onset at the same years of study addressed by

the question about reading habits. Therefore, we found an

interesting and significant association between incidence of

myopia development and number of reading hours during the

same stage of life. This association lost significance when

controlling by parental history of myopia, indicating that

the association was due to genetic factors or early rearing

Downloaded By: [informa internal users] At: 16:02 5 July 2007

Family history and reading habits in adult-onset myopia

conditions rather than hours of reading per se. Besides, the

difference between amount of reading by the groups in the

present study was only about 1 hour per day, which seems to

be rather small. It might, however, be of significance over a

long academic study period.

The lower limit proposed for myopia here (-0.75 diopters

spherical equivalent in either eye) is the same used by Zadnik

et al.,7 better for us than the reference value of -0.50 used in

many other myopia studies. In fact, among the 116 subjects

in the control group, 14 had a spherical equivalent of -0.50,

and five of them did not use lenses at all. On the other hand,

in the myopic group, every subject used lenses. In other

words, if we had used a mean spherical equivalent criterion

of -0.50 diopters, we would have included asymptomatic

subjects not using lenses. Future studies could address the

question about which spherical equivalent cut off has clinical relevance.

This study does not compare emmetropes with myopes,

because a small number of hyperopic subjects who could

escape detection by the fogging technique may have been

included in the control group. Family history of hyperopia

is protective against myopia development in children.49 It

is possible that the significance of the difference that we

observed, between family histories of control and myopic

groups, could have been enhanced by the inclusion of some

hyperopic subjects in the control group.

The present study shows that adult-myopia is associated

with family history and reading habits. Regression

analysis showed that the association was more robust

with family history, in a similar manner as Zadnik et al.7

found in children. Although this study does not prove the

hypothesis that reading is a causal factor in adult-myopia,

other prospective studies33,34,43 have provided support for it,

showing that intense nearwork is associated with the earliness of onset and rate of progression of myopia in adults.

Therefore, while it is likely that reading habits are a causal

factor in adult-myopia, genetic influences also must not be

overlooked.

Parental history of myopia has been associated with

myopia in children.79 It has been argued whether this is

an effect of shared genes or whether parents create a

special environment (for example, induce more reading) for

myopic children. The present study has found an association

between parental history and the development of myopia in

adults, for whom their parents habits have far less importance in creating their environment at the time of myopia

onset than when they were children. Therefore it is possible

that parental history represents the genetic aspect of this

disease.

Youth- and adult-onset myopia have been separated

because they could have somewhat different origins.45 The

values of refractive error are generally lower in adult-onset

than in youth-onset myopia,36,45 and myopia that develops

at a younger age stabilizes sooner.44 However, biometric

studies32,3742 have shown that both youth- and adult-onset

myopias are axial in origin, and the present study supports

313

the idea that both have similar risk factors. Therefore we conclude that both types of myopia may be similar in origin, with

similarly predominant roles for family history and genetic

factors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Leon B. Ellwein, National Eye Institute,

Bethesda, Maryland, for his comments and questions,

and William K. Stell, University of Calgary Faculty of

Medicine, Alberta, Canada, for his editorial comments on

the manuscript.

References

1.

Negrel AD, Maul E, Pokharel GP, Zhao J, Ellwein LB.

Refractive Error Study in Children: Sampling and measurement methods for a multi-country survey. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129:421426.

2. Zhao J, Pan X, Sui R, Munoz SR, Sperduto RD, Ellwein

LB. Refractive Error Study in Children: Results from

Shunyi District, China. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129:427

435.

3. Pokharel GP, Negrel AD, Munoz SR, Ellwein LB. Refractive Error Study in Children: Results from Mechi Zone,

Nepal. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129:436444.

4. Maul E, Barroso S, Munoz SR, Sperduto RD, Ellwein

LB. Refractive Error Study in Children: Results from

La Florida, Chile. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129:445454.

5. Saw SM, Wu HM, Seet B, Wong TY, Yap E, Chia KS,

Stone RA, Lee L. Academic achievement, close up work

parameters, and myopia in Singapore military conscripts.

Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:855860.

6. Wu MM, Edwards MH. The effect of having myopic

parents: An analysis of myopia in three generations. Optom

Vis Sci. 1999;76:387392.

7. Zadnik K, Satariano WA, Mutti DO, Sholtz RI, Adams AJ.

The effect of parental history of myopia on childrens eye

size. JAMA. 1994;271:13231327.

8. Pacella R, McLellan J, Grice K, Del Bono EA, Wiggs JL,

Gwiazda JE. Role of genetic factors in the etiology of

juvenile-onset myopia based on a longitudinal study of

refractive error. Optom Vis Sci. 1999;76:381386.

9. Goss DA, Jackson TW. Clinical findings before the onset

of myopia in youth: 4. Parental history of myopia. Optom

Vis Sci. 1996;73:279282.

10. Parssinen O, Leskinen AL, Era P, Heikkinen E. Myopia, use

of eyes, and living habits among men aged 3337 years.

Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1985;63:395400.

11. Hepsen IF, Evereklioglu C, Bayramlar H. The effect

of reading and near-work on the development of myopia

in emmetropic boys: A prospective, controlled, three-year

follow-up study. Vision Res. 2001;41:25112520.

12. Wong L, Coggon D, Cruddas M, Hwang CH. Education,

reading, and familial tendency as risk factors for myopia in

Downloaded By: [informa internal users] At: 16:02 5 July 2007

314

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

R. Iribarren et al.

Hong Kong fishermen. J Epidemiol Community Health.

1993;47:5053.

Zylbermann R, Landau D, Berson D. The influence of study

habits on myopia in Jewish teenagers. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1993;30:319322.

Saw SM, Chua WH, Hong CY, Wu HM, Chan WY, Chia

KS, Stone RA, Tan D. Nearwork in Early-Onset Myopia.

Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:332339.

Adams DW, McBrien NA. Prevalence of myopia and

myopic progression in a population of clinical microscopists. Optom Vis Sci. 1992;69:467473.

Saw SM, Hong RZ, Zhang MZ, Fu ZF, Ye M, Tan D, Chew

SJ. Near-work activity and myopia in rural and urban

schoolchildren in China. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus.

2001;38:149155.

Angle J, Wissmann DA. The epidemiology of myopia. Am

J Epidemiol. 1980;111:220228.

Dunphy EB, Stoll MR, King SH. Myopia among American

male graduate students. Am J Ophthalmol. 1968;65:518

521.

Al-Bdour MD, Odat TA, Tahat AA. Myopia and level of

education. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2001;11:15.

Paritsis N, Sarafidou E, Koliopoulos J, Trichopoulos D.

Epidemiologic research on the role of studying and urban

environment in the development of myopia during schoolage years. Ann Ophthalmol. 1983;15:10611065.

Richler A, Bear JC. Refraction, nearwork and education.

A population study in Newfoundland. Acta Ophthalmol

(Copenh). 1980;58:468478.

Rosner M, Belkin M. Intelligence, education, and myopia

in males. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987;105:15081511.

Wu HM, Seet B, Yap EP, Saw SM, Lim TH, Chia KS.

Does education explain ethnic differences in myopia

prevalence? A population-based study of young adult males

in Singapore. Optom Vis Sci. 2001;78:234239.

Sperduto RD, Seigel D, Roberts J, Rowland M. Prevalence

of myopia in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983;

101:405407.

Wang Q, Klein BE, Klein R, Moss SE. Refractive status

in the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci.

1994;35:43444347.

Klein R, Klein BE, Lee KE, Cruickshanks KJ, Chappell RJ.

Changes in visual acuity in a population over a 10-year

period: The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology.

2001;108:17571766.

National Eye Institute, Bethesda, MD 20892-2510, USA.

Familial aggregation and prevalence of myopia in the Framingham Offspring Eye Study. The Framingham Offspring

Eye Study Group. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:326332.

Aine E. Refractive errors in a Finnish rural population. Acta

Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1984;62:944954.

Fledelius HC. Is myopia getting more frequent? A crosssectional study of 1416 Danes aged 16 years+. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1983;61:545559.

Attebo K, Ivers RQ, Mitchell P. Refractive errors in an older

population: The Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:10661072.

31. Lin LL, Shih YF, Lee YC, Hung PT, Hou PK. Changes

in ocular refraction and its components among medical

students: A 5-year longitudinal study. Optom Vis Sci.

1996;73:495498.

32. Kinge B, Midelfart A, Jacobsen G, Rystad J. Biometric

changes in the eyes of Norwegian university students: A

three-year longitudinal study. Acta Ophthalmol Scand.

1999;77:648652.

33. Kinge B, Midelfart A, Jacobsen G, Rystad J. The influence

of near-work on development of myopia among university

students: A three-year longitudinal study among engineering students in Norway. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2000;

78:2629.

34. Fledelius HC. Myopia profile in Copenhagen medical

students 199698: Refractive stability over a century

is suggested. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2000;78:501

505.

35. Parssinen TO. Relation between refraction, education,

occupation, and age among 26- and 46-year-old Finns.

Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1987;64:136143.

36. Midelfart A, Aamo B, Sjhaug KA, Dysthe BE. Myopia

among medical students in Norway. Acta Ophthalmol

Scand. 1992;70:317322.

37. McBrien NA, Millodot M. A biometric investigation of

late onset myopic eyes. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1987;

65:461468.

38. Grosvenor T, Scott R. Three-year changes in refraction

and its components in youth-onset and early adult-onset

myopia. Optom Vis Sci. 1993;70:677683.

39. Grosvenor T, Scott R. Comparison of refractive components in youth-onset and early adult-onset myopia. Optom

Vis Sci. 1991;68:204209.

40. Fledelius HC. Adult onset myopia: Oculometric features.

Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1995;73:397401.

41. Katz J, Tielsch JM, Sommer A. Prevalence and risk factors

for refractive errors in an adult inner city population. Invest

Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:334340.

42. McBrien NA, Adams DW. A longitudinal investigation of

adult-onset and adult-progression of myopia in an occupational group. Refractive and biometric findings. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:321333.

43. Ellingsen KL, Nizam A, Ellingsen BA, Lynn MJ. Agerelated refractive shifts in simple myopia. J Refract Surg.

1997;13:223228.

44. Bullimore MA, Jones LA, Moeschberger ML, Zadnik K,

Payor RE. A retrospective study of myopia progression in

adult contact lens wearers. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002

Jul;43(7):21102113.

45. Grosvenor T. A review and a suggested classification

system for myopia on the basis of age-related prevalence

and age of onset. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1987;64:545

554.

46. Fledelius HC. Myopia of adult onset: Can analyses be based

on patient memory? Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1995;73:394

396.

47. Rah MJ, Mitchell GL, Bullimore MA, Mutti DO, Zadnik

K. Prospective quantification of near work using the

Downloaded By: [informa internal users] At: 16:02 5 July 2007

Family history and reading habits in adult-onset myopia

experience sampling method. Optom Vis Sci. 2001;78:

496502.

48. Walline JJ, Zadnik K, Mutti DO. Validity of surveys reporting myopia, astigmatism, and presbyopia. Optom Vis Sci.

1996;73:376381.

315

49. Hui J, Peck L, Howland HC. Correlations between familial

refractive error and childrens non-cycloplegic refractions.

Vision Res. 1995;35:13531358.

Downloaded By: [informa internal users] At: 16:02 5 July 2007

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Senses and Emotions in TCMDocumento9 pagineSenses and Emotions in TCMRafael IribarrenNessuna valutazione finora

- Title 100 Cases Histories in Clinical Medicine For MRCP (Part-1) (PDFDrive - Com) - 1 PDFDocumento395 pagineTitle 100 Cases Histories in Clinical Medicine For MRCP (Part-1) (PDFDrive - Com) - 1 PDFশরীফ উল কবীর50% (4)

- Case SheetDocumento5 pagineCase SheetvisweswarkcNessuna valutazione finora

- Learn About CataractsDocumento41 pagineLearn About CataractsRizkyAgustriaNessuna valutazione finora

- KERATOCONUSDocumento22 pagineKERATOCONUSAarush DeoraNessuna valutazione finora

- 2015 7th Jarvis Physical Examination and Health Assessment Chapter 14Documento13 pagine2015 7th Jarvis Physical Examination and Health Assessment Chapter 14addNessuna valutazione finora

- OCT Guide To InterpretingDocumento98 pagineOCT Guide To InterpretingCambed100% (6)

- Accomodation CycloDocumento6 pagineAccomodation CycloRafael IribarrenNessuna valutazione finora

- Pasaje de Los Rayos in Vitro en Un Lente de Un Pez: Jagger - Sands 1999 (Vision Research)Documento2 paginePasaje de Los Rayos in Vitro en Un Lente de Un Pez: Jagger - Sands 1999 (Vision Research)Rafael IribarrenNessuna valutazione finora

- Alendronato 2017Documento1 paginaAlendronato 2017Rafael IribarrenNessuna valutazione finora

- CIEMS - Lens Power - 2012Documento8 pagineCIEMS - Lens Power - 2012Rafael IribarrenNessuna valutazione finora

- Villa Maria - 2016Documento10 pagineVilla Maria - 2016Rafael IribarrenNessuna valutazione finora

- Normal Postnatal Ocular DevelopmentDocumento23 pagineNormal Postnatal Ocular DevelopmentSi PuputNessuna valutazione finora

- Superficial Corneal Injury and Foreign BodyDocumento1 paginaSuperficial Corneal Injury and Foreign BodyandinurulpratiwiNessuna valutazione finora

- AMO AR40 Spec SheetDocumento2 pagineAMO AR40 Spec Sheetmaricelazayda100% (1)

- Differential Diagnosis of Red EyeDocumento1 paginaDifferential Diagnosis of Red EyedsacciNessuna valutazione finora

- Assignment 2022 B213298B OPTC201Documento4 pagineAssignment 2022 B213298B OPTC201Kudzai RusereNessuna valutazione finora

- Relationship Between Accommodative and Vergence DysfunctionsDocumento11 pagineRelationship Between Accommodative and Vergence DysfunctionsPierre A. RodulfoNessuna valutazione finora

- Common Causes of BlindnessDocumento58 pagineCommon Causes of BlindnesskaunaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ophthalmic Administration. ChecklistDocumento4 pagineOphthalmic Administration. ChecklistKobe Bryan GermoNessuna valutazione finora

- Use of Dyes in OphthalmologyDocumento4 pagineUse of Dyes in OphthalmologyMaulana MalikNessuna valutazione finora

- Glaucoma QuizDocumento2 pagineGlaucoma QuizvoodooariaNessuna valutazione finora

- Myopia Updates II Proceedings of The 7th International Conference On Myopia 1998Documento167 pagineMyopia Updates II Proceedings of The 7th International Conference On Myopia 1998Anonymous f8j0UUNessuna valutazione finora

- VISUSDocumento46 pagineVISUSIsmaaNessuna valutazione finora

- Department of Labor: ls-205Documento2 pagineDepartment of Labor: ls-205USA_DepartmentOfLaborNessuna valutazione finora

- Complications of Pediatric Cataract Surgery and Intraocular Lens ImplantationDocumento4 pagineComplications of Pediatric Cataract Surgery and Intraocular Lens ImplantationnurhariNessuna valutazione finora

- Herpetic Keratitis: Jenan GhaithDocumento8 pagineHerpetic Keratitis: Jenan GhaithJenan GhaithNessuna valutazione finora

- CHAPTER I Makalah ZuhryDocumento6 pagineCHAPTER I Makalah ZuhryFaizal IkhsanNessuna valutazione finora

- Retinopathy of PrematurityDocumento3 pagineRetinopathy of PrematurityluckydrewNessuna valutazione finora

- Diabetic Retinopathy Treatment in MumbaiDocumento7 pagineDiabetic Retinopathy Treatment in MumbaiCharvi JainNessuna valutazione finora

- The Pediatric DispenserDocumento12 pagineThe Pediatric DispenserTuan DoNessuna valutazione finora

- Ischemic Optic NeuropathyDocumento52 pagineIschemic Optic NeuropathySriniwasNessuna valutazione finora

- Gambaran Penderita Infeksi Mata Di Rumah Sakit Mata Manado Provinsi Sulawesi Utara Periode Juni 2017 - Juni 2019Documento5 pagineGambaran Penderita Infeksi Mata Di Rumah Sakit Mata Manado Provinsi Sulawesi Utara Periode Juni 2017 - Juni 2019Darwin ThenNessuna valutazione finora

- The Dry EyeDocumento8 pagineThe Dry EyeMohit BooraNessuna valutazione finora

- Ophthalmology Medical Device Sales in Detroit MI Resume Mark ZelenakDocumento2 pagineOphthalmology Medical Device Sales in Detroit MI Resume Mark ZelenakMarkZelenakNessuna valutazione finora

- Common Ophthalmic Eye DropsDocumento13 pagineCommon Ophthalmic Eye DropsYew JoanneNessuna valutazione finora