Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Esophagi T Is

Caricato da

Rizaldy KehiTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Esophagi T Is

Caricato da

Rizaldy KehiCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Consultant on Call

GASTROENTEROLOGy

Peer Reviewed

Sally Bissett, BVSc, MVSc, DACVIM

Regional Veterinary Emergency and Specialty Center

Turnersville, New Jersey

Esophagitis

PROFILE

Definition

Esophagitis is inflammation of the esophageal

mucosa.

Prevalence in dogs and cats is unknown, but

underdiagnosis is likely, as clinical signs can be

subtle or frequently confused with vomiting.

Pay particular attention to pets that start vomiting within hours to days of anesthesia, as

anesthesia-associated gastroesophageal reflux

(GER) is a common cause of esophagitis.

Geographic factors are unlikely to influence

most cases unless Spirocerca lupi is endemic.

Signalment

Any dog or cat may develop esophagitis once

esophageal mucosal injury occurs.

Certain canine breeds (eg, brachycephalic

breeds, shar-peis) are at increased risk for

hiatal hernia and abnormal lower esophageal

sphincter (LES) function, placing them at

greater risk for GER-induced esophagitis.

Female dogs are at increased risk for

esophageal strictures (sequela of esophagitis)

compared with males, although the reason is

unclear.

Causes

Chemical or mechanical injury to esophageal

mucosa:

Most frequently results from GER at time

of general anesthesia, although other causes

of GER exist (eg, frequent or persistent

vomiting, abnormal LES function, brachycephalic airway obstruction syndrome

[BAOS]).

Can also result from caustic substance

ingestion (eg, strong alkalis in cleaning

products), retention of certain medications

within the esophageal lumen (pill esophagitis, which is well reported in cats1), and

radiation-induced cellular injury.

Ingestion of abrasive or sharp foreign

material.

In dogs, esophageal inflammation associated

with infection (eg, Pythium insidiosum, S lupi)

and allergy can cause pyogranulomatous and

eosinophilic esophagitis, respectively.2

Retention of hair balls (trichobezoars) within

the esophagus has been associated with

esophageal strictures in cats.

Presumably plays a role in development of

esophagitis.

Risk Factors

GER is associated with anesthesia, frequent

or persistent vomiting, and abnormal LES

function (eg, hiatal hernia, BAOS).

Foreign body ingestion/injury (eg, bones,

plastic, trichobezoars [cats]).

Certain oral medications (eg, doxycycline,

clindamycin, bisphosphonates).

Caustic substance ingestion (eg, strong alkali

or acidic cleaning products).

Radiation therapy in proximity of the esophagus.

CONTINUES

BAOS = brachycephalic airway obstruction syndrome, GER = gastroesophageal reflux, LES = lower esophageal sphincter

Consultant on Call / NAVC Clinicians Brief / June 2012 .......................................................................................................................................................................23

Consultant on Call

CONTINUED

Pathophysiology

For GER-induced chemical injury to

esophageal mucosa, both the character of reflux (pH, bile acids, pepsin,

trypsin content) and length of contact

time are important determinants of

injury.

Clinical Signs

Because most pets with esophagitis

present for vomiting, always attempt

to differentiate vomiting from regurgitation (Table). Unlike vomiting,

regurgitation is a passive process that

typically occurs without warning.

Dysphagia, gagging, ptyalism,

odynophagia (painful swallowing),

exaggerated swallowing or head and

neck movements, lip licking, weight

loss, inappetence, and coughing may

be present.

Owners often underappreciate

these signs.

Cats may present with signs of apparent respiratory distress without evidence of aspiration pneumonia.

Observing the pet while it eats is an

important initial diagnostic investigation when history fails to confirm

regurgitation or vomiting.

Pain Index

General signs of malaise (inappetence, lethargy), ptyalism, and dysphagia may indicate esophageal pain.

DIAGNOSIS

Definitive Diagnosis

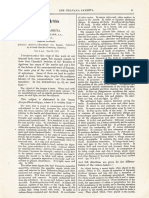

Requires direct examination of the

esophageal mucosa via esophagoscopy.

Mucosa may appear hyperemic;

may contain erosions, ulceration,

exudation, or fibrosis; or may

appear granular or more friable

than normal (Figure 1).

Repetitive damage to distal

esophageal mucosa may result in

Barretts esophagus (replacement of

squamous epithelium with metaplastic columnar epithelia), which

appears more reddish.

Endoscopy-negative esophagitis

described in humans may occur in

dogs or cats.

Term is used when there is no evidence of gross mucosal lesions on

esophagoscopy, but clinical signs

and histopathology of esophageal

biopsies support diagnosis of reflux

esophagitis.

Differential Diagnosis

Other differentials: primary esophageal

motility disorders (eg, idiopathic megaesophagus, myasthenia gravis) and

esophageal masses or obstructive lesions.

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory findings are often unremarkable.

Remarkable findings will not be

specific for esophagitis.

Imaging

Survey Radiography

Survey radiography is always indicated

for initial diagnostic workup of regurgitation or suspected esophagitis.

While sensitive for identifying

esophageal foreign body, radiographs are often unremarkable or

nonspecific for other causes of

esophagitis (eg, regional or generalized megaesophagus).

Radiographic findings include

hiatal hernia, aspiration pneumonia,

or signs of esophageal perforation

(pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, mediastinal fluid).

Contrast Esophagram (Barium Swallow)

Contrast esophagram is more sensitive than survey radiographs for

detecting esophageal obstructive

lesions (strictures, masses, radiolucent

foreign body), motility disorders, and

GER or hiatal hernia that may cause

or contribute to esophagitis.

Typically, start with liquid barium,

followed by barium-coated canned

food, then kibble.

Avoid sedation if possible because

of its effect on esophageal motility

and LES function.

Table. Differentiating Regurgitation from Vomiting

Clinical Sign

Regurgitation

Vomiting

Prodromal nausea

Absent

Present

Abdominal effort*

Absent

Present

Timing of food ejection

Immediate or delayed

Delayed (minutes to hours)

Character of food ejected

Undigested

Partially digested, bile

stained, pH <5

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

For more on differentiating these two

clinical signs, see Regurgitation or

Vomiting? by Dr. Alex Gallagher on

page 33.

*Typically the most reliable sign recognized by owners

24 .......................................................................................................................................................................NAVC Clinicians Brief / June 2012 / Consultant on Call

1

Endoscopic images of (A) smooth, glistening, pale pink normal canine esophageal mucosa

and (B) erythematous and irregular canine esophageal mucosa typical of esophagitis with

retained food material.

Esophagoscopy

Direct mucosal examination via

endoscopy is the most sensitive test

for identifying esophagitis but does

not detect esophageal motility disorders, which are common in dogs.

Perform contrast esophagram

before endoscopy unless the index

of suspicion for esophagitis, foreign

body, or stricture is high.

See Definitive Diagnosis for common gross endoscopic lesions of

esophagitis.

Compared with GER, pill esophagitis

is typically focal, is circumferential,

and involves the proximal third of the

esophagus.

Esophagoscopy may be helpful for

identifying hiatal hernia and provides

a means of obtaining diagnostic

esophageal specimens (brush cytology

or biopsy).

Absence of mucosal abnormalities

does not preclude esophagitis.

Other Diagnostics

Esophageal Cytology or Histopathology

Often necessary for identification of

eosinophilic, infectious, and neoplastic causes of esophagitis.

Biopsy may also be helpful for diagnosing reflux esophagitis when no

gross mucosal lesions are present.

Obtaining esophageal biopsy specimens from dogs and cats can be

difficult and requires new (sharp)

endoscopy pinch biopsy forceps or

suction capsule biopsy instrument.

Distal Esophageal pH & Impedance

Testing

Advanced diagnostics used for diagnosing GER in humans.

Equipment and expertise for use in

veterinary medicine not readily

available.

TREATMENT

In general, almost always medical

treatment on outpatient basis.

Surgical intervention (eg, BAOS,

hiatal hernia, LES dysfunction

unresponsive to medical therapy)

is occasionally required.

Hospitalization may be required for

fluid therapy or nutritional support if

regurgitation is severe or for treatment of aspiration pneumonia.

Medical

Effective gastric acid suppression,

especially if ongoing GER is present,

is the most important aspect of

esophagitis treatment.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are

superior to H2-receptor antagonists

(H2RAs) for managing esophagitis

in humans.

Recent work also supports their

superior antisecretory effects in dogs

(feline studies not yet conducted).

If PPI therapy is cost-prohibitive,

consider high-dose H2RAs.

Time to maximal effect for PPIs

is likely 24 days but suppression

of intragastric pH in dogs is

already superior to H2RAs by day

2 of therapy.

Avoid coadministration of PPIs

and H2RAs, as H2RAs reduce

PPI effectiveness. With severe

esophagitis, antacids may improve

intragastric pH control during

first 2448 hours of PPI therapy.

Prokinetic agents and sucralfate are

frequently used to manage esophagitis

in dogs and cats.

Prokinetic drugs increase LES tone,

accelerate gastric emptying, and

may improve esophageal contractility (cats only).

In humans, cisapride is generally

considered more effective than

metoclopramide.

Sucralfate provides cytoprotective

effects to the esophageal mucosa.

Additional benefits of adding

sucralfate to acid suppression

prokinetic are unclear.

Topical analgesia may be useful to

reduce discomfort associated with

severe forms of esophagitis.

CONTINUES

BAOS = brachycephalic airway obstruction syndrome, GER = gastroesophageal reflux, H2RA = H2-receptor antagonist, LES = lower esophageal sphincter,

PPI = proton pump inhibitor

Consultant on Call / NAVC Clinicians Brief / June 2012 .......................................................................................................................................................................25

Consultant on Call

CONTINUED

Nutritional Aspects

Smaller meal volumes and fat restriction help enhance gastric emptying

and reduce gastric acid production.

Consider gastric feeding tube for animals with poor body condition that

are not eating well or if esophagitis is

severe and the pet is not expected to

eat within next 35 days.

Activity

Restrict activity for 12 hours following meals.

caine or 2% lidocaine jelly at 45

mg/kg (1.82.3 mg/lb) PO q6h for

14 days.

Approximately 0.1 mL/kg (0.05

mL/lb) of 4% lidocaine or 0.2

mL/kg (0.1 mL/lb) of 2% lidocaine.

Aluminum or magnesium hydroxide

antacids: 0.5 mL/kg (0.2 mL/lb) of

regular-strength formulations PO

q46h for first 2448 hours of PPI

therapy (see Treatment, Medical).

IN GENERAL

Relative Cost

Cost of diagnosis and management of

esophagitis varies greatly, depending

on cause and severity and whether

presumptive versus definitive diagnosis is made: $$-$$$$$

Cost Key

FOLLOW-UP

$ = up to $100

$$$$ = $501$1000

$$ = $101$250 $$$$$ = more than $1000

MEDICATIONS

Acid Suppression

PPI (eg, omeprazole, pantoprazole):

12 mg/kg/day (0.50.9 mg/lb/day)

PO or IV, 2030 min before eating

and not broken or chewed (oral form).

Can administer delayed-release

forms of omeprazole q24h.

q12h administration is ideal for

immediate-release liquid forms.

OR

High-dose H2RA (eg, famotidine):

2 mg/kg (0.9 mg/lb) PO q12h.

Prokinetics

Metoclopramide: 0.20.4 mg/kg

(0.10.2 mg/lb) PO q8h.

OR

Cisapride: 0.5 mg/kg (0.2 mg/lb)

PO q8h.

Other Agents

Sucralfate: 0.25 g (cat) or 1 g (large

dog) PO q8h, ideally in liquid form.

Topical analgesia: 4% viscous lido-

Patient Monitoring

Observe for signs of aspiration pneumonia (increased respiratory rate or

effort, cough) and progression of

dysphagia or regurgitation.

Complications

Aspiration pneumonia.

Benign esophageal stricture.

Esophageal perforation (most often

associated with esophageal foreign

body).

At-Home Treatment

Owners should offer small frequent

feedings of a soft, nonabrasive, fatrestricted food.

Future Follow-up

Consider esophagoscopy to detect

(and treat) strictures if regurgitation

persists or progresses in first 12

weeks of therapy.

$$$ = $251$500

Prognosis

Very good to excellent if no complications occur and cause can be

removed.

Good to grave if esophageal perforation or benign esophageal stricture(s)

develop.

Prevention

Use doxycycline liquid versus tablets

when possible.

Advise clients to administer oral

medication with food or follow

medication with a water bolus.

Consider acid suppression (ideally

PPI) with frequent or persistent vomiting and prior to anesthesia for pets

at high risk for GER.3

Avoid prolonged fasting (>18

hours) before anesthesia.4

See Aids & Resources, back page, for

references & suggested reading.

In general, esophagitis can be treated on an outpatient basis,

although surgical intervention is occasionally required.

GER = gastroesophageal reflux, H2RA = H2-receptor antagonist, PPI = proton pump inhibitor

26 .......................................................................................................................................................................NAVC Clinicians Brief / June 2012 / Consultant on Call

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Sds Agk-100 - Drew MarineDocumento13 pagineSds Agk-100 - Drew MarineandreiNessuna valutazione finora

- Nursing Care Planpulmonary TuberculosisDocumento20 pagineNursing Care Planpulmonary Tuberculosisgandhialpit100% (5)

- TomatDocumento1 paginaTomatRizaldy KehiNessuna valutazione finora

- TesDocumento1 paginaTesRizaldy KehiNessuna valutazione finora

- Glaucoma (NW)Documento47 pagineGlaucoma (NW)calvinanang100% (1)

- GerdDocumento18 pagineGerdMeliana OctaviaNessuna valutazione finora

- Gastroesofag RefluxDocumento4 pagineGastroesofag RefluxRizaldy KehiNessuna valutazione finora

- Acid Reflux and OesophagitisDocumento3 pagineAcid Reflux and OesophagitisRizaldy KehiNessuna valutazione finora

- VomitingDocumento2 pagineVomitingPhysiology by Dr RaghuveerNessuna valutazione finora

- Rumination Disorder On DSM VDocumento6 pagineRumination Disorder On DSM VCamilo TovarNessuna valutazione finora

- Greco Roman and Byzantine Views On ObesityDocumento18 pagineGreco Roman and Byzantine Views On Obesityjuanbususto4356Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ketorolac vs. TramadolDocumento5 pagineKetorolac vs. TramadolRully Febri AnggoroNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To Patient - S Medical Chart (2012) PDFDocumento29 pagineIntroduction To Patient - S Medical Chart (2012) PDFFrancinetteNessuna valutazione finora

- AJEERNA (Indigestion)Documento37 pagineAJEERNA (Indigestion)m gouriNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 59 - Antiemetic AgentsDocumento11 pagineChapter 59 - Antiemetic AgentsJonathonNessuna valutazione finora

- Wasting Disease: Erosion! A Diagnosis, Prevention and ManagementDocumento3 pagineWasting Disease: Erosion! A Diagnosis, Prevention and ManagementyulisNessuna valutazione finora

- Indmedgaz71838 0031 PDFDocumento10 pagineIndmedgaz71838 0031 PDFPrasanth mallavarapuNessuna valutazione finora

- Infectious DiseaseDocumento82 pagineInfectious DiseaseMedical videos67% (3)

- NCP - Nausea and VomitingDocumento9 pagineNCP - Nausea and VomitingMikko Anthony Pingol Alarcon77% (13)

- Meknisme MuntahDocumento3 pagineMeknisme MuntahVetlife DvpNessuna valutazione finora

- Drug Study 2Documento7 pagineDrug Study 2Jediale CarcelerNessuna valutazione finora

- Sanguinaria CanadensisDocumento4 pagineSanguinaria CanadensisMuhammad Mustafa IjazNessuna valutazione finora

- Casepres NCPDocumento6 pagineCasepres NCPdencio1992Nessuna valutazione finora

- Differences in PONV Incidence Between Active & Passive SmokersDocumento15 pagineDifferences in PONV Incidence Between Active & Passive SmokersBreinz HydeNessuna valutazione finora

- Dursban 480 Ec LabelDocumento30 pagineDursban 480 Ec LabelJurgen SchirmacherNessuna valutazione finora

- Health Benefits of Drinking Ginger TeaDocumento3 pagineHealth Benefits of Drinking Ginger TeaMarynell ValenzuelaNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 1 Herbs That Release The ExteriorDocumento74 pagineChapter 1 Herbs That Release The ExteriorCarleta Stan100% (2)

- Nursing Care For Patient With HIV AIDSDocumento28 pagineNursing Care For Patient With HIV AIDSDessyana Paulus100% (1)

- Pain Assessment FormDocumento1 paginaPain Assessment FormPipit100% (1)

- Hiatus Hernia - Chinese Herbs, Chinese Medicine, AcupunctureDocumento6 pagineHiatus Hernia - Chinese Herbs, Chinese Medicine, AcupunctureCarlCordNessuna valutazione finora

- 2022 Seminar Nasional Penelitian dan Pengabdian Kepada Masyarakat (SNPPKM) Focuses on PONV Differences in ERACS and Elective C-Section MethodsDocumento6 pagine2022 Seminar Nasional Penelitian dan Pengabdian Kepada Masyarakat (SNPPKM) Focuses on PONV Differences in ERACS and Elective C-Section MethodsNers RidaNessuna valutazione finora

- Faktur Pembelian Obat 2020Documento64 pagineFaktur Pembelian Obat 2020Dinda NugrahanNessuna valutazione finora

- Summary of Face Reading in Chinese MedicineDocumento25 pagineSummary of Face Reading in Chinese MedicineDoña InesNessuna valutazione finora

- TM 55 1905 242 14Documento1.001 pagineTM 55 1905 242 14mercury7k29750Nessuna valutazione finora

- Gastroenteritis in ChildrenDocumento48 pagineGastroenteritis in ChildrenKelsingra FitzChivalry FarseerNessuna valutazione finora

- CopperToxicity PDFDocumento7 pagineCopperToxicity PDFAntonio C. KeithNessuna valutazione finora