Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Soto Et Al. 2015. An Ecological Perspective On Diabetes Self-Care Support, Self-Management Behaviors, and Hemoglobin A1C Among Latinos

Caricato da

Natalia MocTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Soto Et Al. 2015. An Ecological Perspective On Diabetes Self-Care Support, Self-Management Behaviors, and Hemoglobin A1C Among Latinos

Caricato da

Natalia MocCopyright:

Formati disponibili

569078

research-article2015

TDEXXX10.1177/0145721715569078Diabetes Support, A1C, and Self-management BehaviorsSoto et al

The Diabetes EDUCATOR

214

An Ecological Perspective on

Diabetes Self-care Support,

Self-management

Behaviors, and Hemoglobin

A1C Among Latinos

Purpose

Sandra C. Soto, MPH

Sabrina Y. Louie, MPH

Andrea L. Cherrington, MD, MPH

Humberto Parada, MPH

Lucy A. Horton, MPH, MS

Guadalupe X. Ayala, PhD, MPH

From San Diego State University/University of California, San Diego Joint

Doctoral Program in Public Health (Health Behavior) and the Institute for

Behavioral and Community Health, San Diego, California (Ms Soto);

Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California (Ms Louie); University

of Alabama at Birmingham, School of Medicine, Division of Preventive

Medicine, Birmingham, Alabama (Dr Cherrington); University of North

Carolina, Chapel Hill, Gillings School of Global Public Health, Chapel Hill,

North Carolina (Mr Parada); Institute for Behavioral and Community

Health, San Diego, California (Ms Horton); and San Diego State University,

Graduate School of Public Health, Division of Health Promotion and

Behavioral Science, and the Institute for Behavioral and Community

Health, San Diego, California (Dr Ayala).

Correspondence to Sandra Soto, MPH, San Diego State University/

University of California, San Diego Joint Doctoral Program in Public Health

(Health Behavior) and the Institute for Behavioral and Community Health,

9245 Sky Park Court, Suite 221, San Diego, CA 92123, USA (Sandra.

soto@mail.sdsu.edu).

Financial Support: Puentes hacia una mejor vida (Bridges to a better life)

was funded by the Peers for Progress network and sponsored by the

American Academy of Family Physicians Foundation (SOOOII24OIGEL).

The authors have no relevant conflict of interest to disclose.

DOI: 10.1177/0145721715569078

2015 The Author(s)

The purpose of this study was to examine the role of self,

interpersonal (ie, family/friend), and organizational (ie,

health care) support in performing diabetes-related selfmanagement behaviors and hemoglobin A1C (A1C)

levels among rural Latinos with type 2 diabetes.

Methods

Cross-sectional data from baseline interviews and medical records were used from a randomized controlled trial

conducted in rural Southern California involving a clinic

sample of Latinos with type 2 diabetes (N = 317). Selfmanagement behaviors included fruit and vegetable

intake, fat intake, physical activity, glucose monitoring,

daily examination of feet, and medication adherence.

Multivariate linear and logistic regression models were

used to assess the relationships of sources of support

with self-management behaviors and A1C.

Results

Higher levels of self-support were significantly associated with eating fruits and vegetables most days/week,

eating high-fat foods few days/week, engaging in physical activity most days/week, daily feet examinations, and

self-reported medication adherence. Self-support was

also related to A1C. Family/friend support was significantly associated with eating fruits and vegetables and

engaging in physical activity most days/week. Health

Volume 41, Number 2, April 2015

Downloaded from tde.sagepub.com at Bobst Library, New York University on May 25, 2015

Diabetes Support, A1C, and Self-management Behaviors

215

care support was significantly associated with consuming fats most days/week.

Conclusions

Health care practitioners and future interventions should

focus on improving individuals diabetes management

behaviors, with the ultimate goal of promoting glycemic

control. Eliciting family/friend support should be encouraged to promote fruit and vegetable consumption and

physical activity.

ype 2 diabetes is widespread in the US, with

an estimated 25.8 million people living with

diabetes and an additional 79 million living

with prediabetes.1 Diabetes disproportionately affects Latinos, who are nearly 2 times

more likely to have diabetes compared to non-Latino

whites.2 Moreover, Latinos tend to be diagnosed with diabetes at younger ages than non-Latino whites, indicating a

greater risk of developing diabetes-related complications

earlier in life (median age of 49 vs 55, respectively).3 A

meta-analysis revealed that compared with non-Latino

whites with diabetes, Latinos with diabetes have approximately 0.5% higher A1C levels.4 Self-management behaviors including consuming a healthy diet and engaging in

regular physical activity, among others, can improve glycemic control and reduce the risk of diabetes-related complications.5 However, Latinos with diabetes generally

report lower rates of self-management behaviors than

non-Latino whites with diabetes.6 Hence, an investigation

into the factors that influence self-management behaviors

in Latinos is warranted.

The social ecological framework (SEF) depicts multiples sources of influence on self-management behaviors (see Figure 1).5 These sources of support range from

the individual to the media each exerting their direct and

indirect influence on a persons ability to engage in diabetes-related self-management behaviors.7,8 According to

the SEF, sources of support for diabetes-related selfmanagement behaviors include the individual with diabetes, interpersonal support (eg, family and friends),

health care professionals, the neighborhood, community

organizations, the workplace, health insurance, and the

media (Figure 1).9 For instance, those with diabetes can

Figure 1. Socio ecological framework of sources of support for diabetes

self-care.

engage in goal setting, a form of self-management support.10 Interpersonal support has also been found to promote self-management behaviors. For example, Fisher et

al11 found that family cohesion was more strongly related

to healthier diet intake and exercise among Latinos than

non-Latino whites with diabetes. Higher levels of support from friends12 and health care professionals13 have

also been associated with improved diabetes management and glycemic control in Latinos and non-Latinos.

The literature also supports the important role that environmental and community sources of support have on

self-management behaviors.14 Individuals with diabetes

who live in neighborhoods with suitable environments

for physical activity and healthy food options are more

likely to engage in physical activity and consume healthier foods.15 Community organizations that provide health

education and promote disease management have also

been linked to improved self-management behaviors

among those with diabetes.16,17 While the literature suggests relationships of various sources of support with

self-management behaviors and A1C, there is limited

evidence for which sources of support are most influential in specific self-management behaviors.

The purpose of this study was to examine the role of

self, interpersonal (ie, family/friend), and organizational

(ie, health care) support in performing diabetes-related

self-management behaviors and A1C levels among rural

Latinos with type 2 diabetes.

Soto et al

Downloaded from tde.sagepub.com at Bobst Library, New York University on May 25, 2015

The Diabetes EDUCATOR

216

Methods

Measures

Study Design

Diabetes Self-management Behaviors

This cross-sectional study used baseline data from a

randomized controlled trial in rural southern California

that included 336 clinic patients with diabetes.18 Data

came from Puentes hacia una mejor vida (Puentes;

Bridges to a Better Life), 1 of 8 international studies testing models of peer support for diabetes control (ie, Peers

for Progress). Puentes was conducted in Imperial County,

the southeastern most county in California along the

US-Mexico border, where 81% of county residents are

Latino and 32% are foreign-born.19

Fruit and vegetable intake, fat intake, physical activity,

glucose monitoring, and foot examinations were measured

using the Summary of Diabetes Self-care Activities scale

previously used with Latino populations.20-22 These behaviors are recommended by the American Association of

Diabetes Educators and the American Diabetes Association

and are the standard of care for self-management education.5 Self-management behaviors were analyzed separately given the low inter-item correlations seen among the

behaviors20 and each behaviors potentially distinct associations with sources of support. Each self-management

behavior was assessed by a single item as follows: On

how many of the last 7 days did you (a) eat 5 or more servings of fruits and vegetables, (b) eat high-fat foods, such as

red meat or full-fat dairy products, (c) participate in at least

30 minutes of physical activity (do not count physical

activity as part of your work), (d) test your blood sugar,

and (e) check your feet? Because there are no firm recommendations for fruit, vegetable, or fat intake related to diabetes control,23 these variables were dichotomized into

whether participants reported consuming these foods a few

days a week (0-3 days) versus most days of the week (4-7

days). Physical activity was dichotomized based on recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention to exercise 5+ days per week versus fewer.24

The blood sugar testing and feet exam items were dichotomized as 7 days per week versus <7 days per week.

Sample and Setting

Between April 2010 and January 2011, participants

were randomly sampled using the medical charts from 3

of 9 clinics that are part of Clnicas de Salud del Pueblo,

Inc, a federally qualified health center with clinic sites

located in Imperial and Riverside counties. All patients

who met these criteria were sampled: (a) a diagnosis of

type 1 or type 2 diabetes, (b) at least 18 years of age, (c)

a recent (within 3 months) A1C value over 7.0%, and (d)

seen at 1 of the 3 clinics within the past 3 months. Fifty

percent of the patients on this list were randomly sampled

and mailed letters of invitation followed by a telephone

call from a research staff member. Patients who agreed

were then screened for eligibility confirming the aforementioned criteria, the patients ability to read in English

or Spanish, and their intention to reside in the study area

for the duration of the study (12 months). Patients were

excluded if they had participated in an intensive diabetes

education program in the past 6 months or if they had a

significant physical or developmental disorder that would

limit participation. All eligible participants signed an

informed consent form and a medical chart release form.

Study instruments and protocols were approved by the

Institutional Review Board of San Diego State University.

Following enrollment and consenting procedures, a

research assistant administered a questionnaire in Spanish

or English based on the patients preference. A research

staff member abstracted the most recent values of A1C

from the patients medical chart.

Fifteen participants were excluded because they did

not self-identify as Latino. Four participants with type 1

diabetes were excluded given differences in the regimens

required for managing these 2 types. The final sample

size for this study was 317.

Medication Adherence

This self-management behavior was assessed using

the 4-item Morisky Medication Adherence scale.25 The

scale has yes/no response options to items such as, Do

you ever forget to take your diabetes medicine?

Consistent with a previous study with this sample,18 medication adherence was dichotomized into adherent (no

report of nonadherence to any item) versus nonadherent

(affirmative response to at least 1 item). Internal consistency with the current sample was .52 compared with .61

previously reported by Morisky and colleagues.25

Hemoglobin A1C

This continuous measure of percentage value for A1C

was obtained from the most recent lab result in the participants medical record within the previous 3 months.

Volume 41, Number 2, April 2015

Downloaded from tde.sagepub.com at Bobst Library, New York University on May 25, 2015

Diabetes Support, A1C, and Self-management Behaviors

217

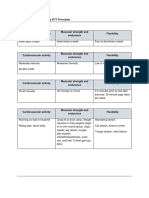

Sources of Support for Diabetes Self-care

Demographic Characteristics

Frequency of support received was assessed using the

Chronic Illness Resource Survey (CIRS),9 previously

translated and validated in a Spanish-speaking sample

with at least 1 chronic disease by Eakin et al.26 The

22-item CIRS assesses the frequency of support from 7

sources in the past 3 months ranging from those closest to

the individual to more distal sources of support: (a) self

(3 items), (b) family/friends (3 items), (c) health care (3

items), (d) neighborhood (4 items), (e) community organizations (3 items), (f) workplace (3 items), and (g) health

insurance/media (3 items; see Table 1). Participants were

asked to respond to items using the following stem: In

the past 3 months..., and response options were on a

5-point Likert scale ranging from none of the time to

all of the time.

To determine whether the sources of support assessed

by the CIRS accurately assessed the sources of support of

the study sample, a factor analysis was conducted using

the samples responses to the CIRS. Principal components analysis using varimax rotation was used to explore

the factors. The variance accounted for by the solution,

the variance accounted for by each individual factor, and

the interpretability of the factors were all evaluated to

initially determine the factor structure. To further confirm

the factor structure, a parallel analysis was used. Based on

a factor analysis in this sample, several changes were

made to the scoring of the CIRS. First, workplace support

was omitted because only 24% of our sample was

employed. Second, the distal sources of support were

removed because of poor factor loadings. As a result, the

following 3 sources of support were examined in this

study: (a) self, (b) family/friends, and (c) health care.

Third, 2 items from the neighborhood support subscale

had high factor loadings on the family/friends subscale

and were therefore included with this subscale (Did you

go to parks for picnics, walks, or other outings? and Did

you eat at a restaurant that had low-fat food choices?).

This is consistent with previous research showing that

park use and going out to eat are social behaviors that

occur most frequently with family and friends.27,28 The

self and health care subscales remained as originally proposed by Eakin and colleagues.26 Mean subscale scores

were obtained, ranging from 1 to 5, with higher scores

indicating more frequent support. Internal consistency for

the self, family/friend, and health care support subscales

were .81, .62, and .62, respectively.

These included age (< 50, 51-57, 58-64, and 65),

gender, marital status (married or living with a partner vs

single, divorced, widowed, or separated), employment

status (employed vs not employed, retired, homemaker,

student), education level (less than high school education

vs high school graduate or greater), and monthly household income (less than $1000 vs $1000 or greater).

Country of birth (Mexico or other country vs US) was

used as a proxy for acculturation. Finally, duration of diabetes diagnosis was included due to its potential influence on self-management behaviors and A1C.29

Data Analyses

Outcome variables included self-management behaviors (treated as categorical) and A1C (treated as continuous). Self-management behaviors were dichotomized as

follows: fruit and vegetable intake and fat intake were

dichotomized into consuming these foods a few days a

week (0-3 days) versus most days of the week (4-7 days),

physical activity was dichotomized into 5 or more days

per week versus <5 days per week, blood glucose monitoring and foot examinations were dichotomized as

7days per week versus <7 days per week, and medication

adherence was dichotomized into adherent versus nonadherent. Because daily glucose monitoring is recommended for those who are prescribed insulin but not

always for those who are not taking insulin,30,31 analyses

with glucose testing as the outcome variable were only

conducted using participants who were prescribed insulin

(n = 91).

Univariate logistic regression models were used to

calculate unadjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence

intervals of the self-management behaviors with self,

family/friend, and health care sources of support.

Univariate linear regression was used to calculate unadjusted parameter estimates and P values for the association of A1C with self, family/friend, and health care

sources of support and covariates. Because HbA1C was

not normally distributed, it was log-transformed for

analyses. The only variables included in the unadjusted

models were the outcome variables and the sources of

support, without the inclusion of any demographic characteristics (e.g., covariates). Covariates associated with

self-management behaviors and A1C at P < .20 were

included in multivariate models.

Soto et al

Downloaded from tde.sagepub.com at Bobst Library, New York University on May 25, 2015

218

Downloaded from tde.sagepub.com at Bobst Library, New York University on May 25, 2015

Item

Did you think about good things you did to take care of your diabetes?

Did you make time to take care of your diabetes?

Did you think about the goals you set for yourself to take care of your

diabetes?

Did your family/friends exercise with you?

Did your family/friends make food for you that was healthy?

Did you share healthy low-fat recipes with family/friends?

Did your doctor/health care provider involve you in making decisions about

your diabetes?

Did your doctor/health care provider listen to what you had to say about your

diabetes?

Did your doctor/health care provider tell you the results of any tests in a way

you could understand?

Did you go to parks for picnics, walks, or other outings?

Did you eat at a restaurant that had low-fat food choices?

Did you walk/exercise outdoors in your neighborhood?

Did you walk/exercise with your neighbors?

Did you go to a local health program or health club?

Did you go to free or low-cost meetings about your diabetes, such as church

groups or community programs?

Did you volunteer at a local organization or for an interest/cause?

Did you have a work schedule that you could change to meet your health

needs?

Were there rules/policies at work that made it easier for you to take care of

your diabetes?

Did you have control over your job duties so that you could still take care of

your diabetes?

Did you have health insurance that covered most of the costs of your medical

care and medicines?

Did you read articles in newspapers/magazines about taking care of your

diabetes?

Have you seen ads about not smoking, eating low-fat foods or getting regular

exercise?

Eakin et al.26

Factor scores not reported if less than .250.

Health insurance/

media

Workplace

Community

organizations

Neighborhood

Health care (HC)

Family/friend (FF)

Self

CIRS Subscalesa

Chronic Illness Resource Survey (CIRS) Factor Analysis Results

Table 1

.753

.430

.392

.792

.677

.597

.313

.262

.258

.843

.837

.817

.456

.705

.714

.753

.296

.718

.575

.323

.804

.760

.740

.293

.296

Factorb

.302

.784

.470

.333

.300

.353

.599

.277

.765

.302

.288

.660

.416

.275

.556

FF

FF

HC

HC

FF

FF

FF

HC

Self

Self

Self

Scales

Diabetes Support, A1C, and Self-management Behaviors

219

Separate multivariate logistic and linear regression

models examined whether sources of support were associated with self-management behaviors and A1C, respectively, after adjusting for covariates. Each multivariate

model controlled for other sources of support. For

example, the model assessing the association between

self-support and physical activity controlled for both

family/friend and health care support. Statistical significance was established at P < .05. Statistical analyses

were performed using SAS Version 9.2 (Cary, North

Carolina, USA).

Results

Participants were, on average, 57 years old (12), primarily female (64%), married (61%), and foreign-born

(79%). Only 24% were currently employed, most had

less than a high school education (70%), and almost half

reported a monthly household income of less than $1000.

The average (SD) A1C in this sample was 8.53% (70

mmol/mol) (1.63% [17.8 mmol/mol]). Half of all participants reported consuming 5 or more servings of fruits

and vegetables on most days of the week. Most participants reported consuming high-fat foods on few days of

the week. One-third reported engaging in at least 30 minutes of physical activity at least 5 days per week. Over

70% of individuals prescribed insulin tested their blood

glucose daily, and of all participants, nearly 70% examined their feet daily. Forty percent of participants were

adherent to their medication regimen. Mean scores for

support were highest for self, followed by health care and

family/friend support (Table 2).

Table 3 provides the logistic regression findings on

the association of sources of support with self-management behaviors. Self-support was consistently and

strongly associated with most self-management behaviors. For example, higher levels of self-support were

associated with 87% higher odds of being adherent to

diabetes medications, 55% higher odds of consuming

fats less frequently, 30% to 40% higher odds of eating

fruits and vegetables on 4 or more days/week, engaging

in physical activity on 5 or more days/week, and conducting daily foot examinations, after adjusting for relevant covariates. Family/friend support was significantly

associated with 70% higher odds of physical activity on

5 or more days/week and eating fruits and vegetables on

4 or more days/week. Health care support was only associated with fat intake. Specifically, after adjusting for

other sources of support and covariates, health care support was associated with more frequent fat intake.

Sources of support were not statistically related to glucose monitoring in participants who were prescribed

insulin in adjusted models.

Self-support was the only source of support that was

significantly associated with lower A1C levels before

and after controlling for covariates ( = 0.16; P = .01)

(Table 4). The exponentiated coefficient for the adjusted

relationship between self-support and A1C was 1.17,

indicating that for a 1-unit increase in self-support, there

was a 17% decrease in A1C.

Discussion

Results indicated that higher levels of self-support

were related to more frequent fruit and vegetable intake,

less frequent fat intake, physical activity on most days of

the week, daily feet examination, improved medication

adherence, and lower A1C in a clinical sample of Latinos

with diabetes. These findings are consistent with previous research indicating that higher self-support for diabetes self-management is associated with a healthier

diet,32,33 physical activity,32-34 and lower A1C.35 However,

most previous research has been conducted with nonLatino populations.32,34,35 Findings for glucose monitoring showed no relationship with sources of support in

multivariate models, though it is possible that the sample

size of 91 was too small to detect significance.

Higher levels of family/friend support were related to

more frequent fruit and vegetable intake and physical

activity. In previous studies with older Mexican

Americans33 and in a mixed-ethnicity sample,14 family

support was also related to improved diet and physical

activity. However, other studies have demonstrated

mixed results. For instance, in a multi-ethnic sample,

Shaw et al36 did not find an association between family

support and fruit, vegetable, and fat intake using the

same measures and cutoff scores used in this study.

Moreover, in an Australian sample, the association of

family support with diet and physical activity was no

longer significant when self-efficacy, an indicator of selfsupport according to the authors, was included in the

model.32 It is notable that fruit and vegetable intake and

physical activity tend to be more socially bound than

other self-management behaviors assessed in this study,

such as daily feet examinations and medication adherence.37 As Sherbourne and colleagues37 observed, social

Soto et al

Downloaded from tde.sagepub.com at Bobst Library, New York University on May 25, 2015

The Diabetes EDUCATOR

220

Table 2

Participant Characteristics (N = 317).

Demographics

% (n) or Mean (SD or lower-upper quartiles)

Female

Age in years

Marital status

Married/living with partner

Single, divorced, windowed, or separated

Employment status

Employed

Unemployed, retired, student, or homemaker

Education

< High school/GED

High school/GED

Household monthly income

<$1,000

$1,000

Country of birth

Mexico or other

US

Diabetes-related

Years with diabetes diagnosis

Hemoglobin A1C% (mmol/mol)

Self-management behaviors

Fruit and vegetable intake (4-7 days/week)

Fat intake (0-3 days/week)

Physical activity (30 min 5 days/week)

Glucose monitoring (7 days/week)a

Daily feet examinations (7 days/week)

Medication adherence (adherent)

Sources of supportb

Self

Family/friend

Health care

64 (202)

57 (12)

61 (192)

39 (125)

24 (76)

76 (240)

70 (222)

30 (94)

47 (144)

53 (160)

79 (249)

21 (67)

13 (11)

8.53 (1.63) (70 [17.8])

50 (158)

80 (252)

33 (104)

74 (67)

69 (219)

39 (123)

3.52 (2.67-4.67)

1.98 (1.25-2.50)

3.28 (2.33-4.00)

Glucose testing among those prescribed insulin (n = 91).

Scores range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating more support.

behaviors including those that are diet related impact the

entire family and therefore require their support for

change. Our findings appear to support the idea that

interpersonal support is important for social behaviors.

In this sample, higher levels of health care support

were related to more frequent fat intake. King et al14

found the same counterintuitive result in a Colorado

sample comprised of 21% Latino participants (N = 463).

In a separate study with 695 Norwegian adults with

diabetes, greater health care support was associated with

poor diet management, although the measure of diet did

not include fat intake.38 The authors suggested that more

supportive health care providers perhaps do not exert

sufficient external pressure to consume a healthful diet.

In the current study, the health care support subscale

contained items reflecting shared decision making and

patient-centered care. It may be that patients who are

active participants in their health care choose not to focus

on fat consumption in their discussions on self-management behaviors with their health care providers. It also

may be the case that health care providers focus on

carbohydrates, specifically, fruit, vegetable, and fiber

intake, and exclude fat intake in their patient counseling.

Given that this is a reoccurring finding, future studies

Volume 41, Number 2, April 2015

Downloaded from tde.sagepub.com at Bobst Library, New York University on May 25, 2015

Downloaded from tde.sagepub.com at Bobst Library, New York University on May 25, 2015

221

OR

95% CI

aOR

95% CI

OR

95% CI

aOR

95% CI

OR

95% CI

aOR

95% CI

1.31**

1.08-1.59

1.26*

1.02-1.57

1.61*

1.21-2.13

1.66**

1.21-2.29

1.10

0.91-1.33

1.00

0.81-1.23

1.43**

1.13-1.81

1.55*

1.17-2.06

1.07

0.77-1.50

1.07

0.73-1.57

0.76*

0.60-0.98

0.71*

0.54-0.94

Fat Intake

0-3 Days/Week

(Reference =

4-7 days)b

1.52***

1.22-1.89

1.29*

1.02-1.63

1.92***

1.43-2.59

1.74***

1.26-2.41

1.2

0.98-1.48

1.14

0.91-1.44

Physical activity

30 Minutes 5

Days/Week

(Reference = 0-4

Days)c

1.71*

1.06-2.94

1.27

0.69-2.34

1.57

0.80-3.06

1.81

0.78-4.21

0.85

0.54-1.33

0.88

0.53-1.44

Glucose

Monitoring 7

Days/Week

(Reference = <7

Days)d

Abbreviations: 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; OR, odds ratio.

a

Adjusted model controlling for other sources of support, gender, and country of birth.

b

Adjusted model controlling for other sources of support, age, education, and gender.

c

Adjusted model controlling for other sources of support and education.

d

Adjusted model controlling for other sources of support and age. Glucose testing analysis only conducted with those who were prescribed insulin (n = 91).

e

Adjusted model controlling for other sources of support, age, and country of birth.

f

Adjusted model controlling for other sources of support and gender.

*P < .05. **P < .01. ***P < .001.

Health care support

Family/friend support

Self support

Fruit and

Vegetable Intake

4-7 Days/Week

(Reference = 0-3

days)a

1.45***

1.18-1.78

1.36*

1.07-1.72

1.48*

1.08-2.02

1.34

0.95-1.90

1.11

0.91-1.37

1.08

0.86-1.36

Daily Feet

Examinations 7

Days/Week

(Reference = <7

Days)e

The Association Between Sources of Support and Self-management behaviors (Logistic Regression Crude and Adjusted Findings).

Table 3

1.70***

1.37-2.10

1.87***

1.47-2.38

1.13

0.86-1.49

0.89

0.65-1.23

1.06

0.87-1.28

0.95

0.76-1.18

Medication

Adherence

(Reference =

Nonadherent)f

The Diabetes EDUCATOR

222

Table 4

The Association Between Sources of Support and the Log of Hemoglobin A1C (Linear Regression Crude and Adjusted

Findings).

Adjusted Modelsa

Crude Models

Self support

Family/friend support

Healthc are support

Standardized B (SE)

P Value

Standardized (SE)

P Value

.17 (.01)

.02 (.01)

.11 (.01)

.002

.72

.05

.16 (.01)

.04 (.01)

.08 (.01)

.01

.49

.14

Adjusted models controlling for education and age.

should explore the qualities of the patient-provider relationship and how they impact patients dietary habits.

Causal inferences cannot be made from this crosssectional study. Longitudinal studies are rare but necessary

for testing the causal path between the relationships examined here.37 Another limitation is that only 3 sources of

support were investigated in this study. Although the CIRS

has worked well in other studies involving Latinos,26,39 the

full scale performed poorly in this sample, and the low

rates of employed participants precluded us from examining workplace support. However, a strength of our study is

that sources of support and self-management behaviors

were examined separately, instead of grouping sources of

support14,39 or self-management behaviors.36,37 Creating

groups has the potential to mask relationships and inflate

others. A second strength of this study was that it involved

rural Latinos, an understudied population with one of the

highest prevalence rates of diabetes in the US.

Implications

This study is one of the first to examine the relationship of self-management behaviors and A1C with multiple sources of support among Latinos. Practitioners

should reinforce self-management behaviors to improve

A1C. However, when targeting diet and physical activity,

interpersonal support should also be promoted in both

research and clinical practice. Health care providers can

encourage these socially based behaviors by inviting and

engaging family members and friends during clinic visits

and diabetes-related counseling sessions.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes

Fact Sheet: National Estimates and General Information on

Diabetes and Prediabetes in the United States. Atlanta, GA:

CDC; 2011.

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Diabetes and

Hispanic Americans. http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/

content.aspx?ID=3324. Updated 2011. Accessed July/17, 2013.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for

Health Statistics, Division of Health Interview Statistics, data

from the National Health Interview Survey. Age-Adjusted incidence of diagnosed diabetes per 1,000 population Aged 1879

years, by race/ethnicity, United States, 1997-2011. http://www.

cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/incidence/fig6.htm. Updated 2013.

Accessed April 2014.

4. Kirk JK, Passmore LV, Bell RA, et al. Disparities in A1C levels

between Hispanic and non-Hispanic white adults with diabetes: a

meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(2):240-246.

5. Funnell MM, Brown TL, Childs BP, et al. National standards for

diabetes self-management education. Diabetes Care. 2011;

34(suppl 1):S89-96.

6. Nwasuruba C, Khan M, Egede LE. Racial/ethnic differences in

multiple self-care behaviors in adults with diabetes. J Gen Intern

Med. 2007;22(1):115-120.

7. Bronfenbrenner U, Bronfenbrenner U. The Ecology of Human

Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge,

MA: Harvard University Press; 2009.

8. Sallis JF, Owen N, Fisher EB. Ecological models of health behavior. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research,

and Practice. 2008;4:465-485.

9. Glasgow RE, Strycker LA, Toobert DJ, Eakin E. A social-ecologic approach to assessing support for disease self-management:

the Chronic Illness Resources Survey. J Behav Med.

2000;23(6):559-583.

10. DeWalt DA, Davis TC, Wallace AS, et al. Goal setting in diabetes

self-management: taking the baby steps to success. Patient Educ

Couns. 2009;77(2):218-223.

Volume 41, Number 2, April 2015

Downloaded from tde.sagepub.com at Bobst Library, New York University on May 25, 2015

Diabetes Support, A1C, and Self-management Behaviors

223

11. Fisher L, Chesla CA, Skaff MM, et al. The family and disease

management in Hispanic and European-American patients with

type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(3):267-272.

12. Gleeson-Kreig J, Bernal H, Woolley S. The role of social support

in the self-management of diabetes mellitus among a Hispanic

population. Public Health Nursing. 2002;19(3):215-222.

13. Delamater AM. Improving patient adherence. Clin Diabetes.

2006;24(2):71-77.

14. King DK, Glasgow RE, Toobert DJ, et al. Self-efficacy, problem

solving, and social-environmental support are associated with

diabetes self-management behaviors. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(4):

751-753.

15. Auchincloss AH, Roux AVD, Mujahid MS, Shen M, Bertoni AG,

Carnethon MR. Neighborhood resources for physical activity and

healthy foods and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus: the multiethnic study of atherosclerosis. Arch Intern Med. 2009; 169(18):1698.

16. Castillo A, Giachello A, Bates R, et al. Community-based diabetes education for Latinos The Diabetes Empowerment Education

Program. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36(4):586-594.

17. Lorig K, Gonzlez VM. Community-based diabetes self-management education: definition and case study. Diabetes Spectrum.

2000;13(4):234-238.

18. Parada H Jr, Horton LA, Cherrington A, Ibarra L, Ayala GX.

Correlates of medication nonadherence among Latinos with type

2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2012;38(4):552-561.

19. U.S. Census Bureau. State and county quickfacts. Imperial

County, California. http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/

06/06025.html. Updated 2012. Accessed May 2014.

20. Toobert DJ, Hampson SE, Glasgow RE. The summary of diabetes

self-care activities measure: results from 7 studies and a revised

scale. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(7):943-950.

21. Ell K, Katon W, Xie B, et al. Collaborative care management of

major depression among low-income, predominantly Hispanic

subjects with diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes

Care. 2010;33(4):706-713.

22. Sarkar U, Fisher L, Schillinger D. Is self-efficacy associated with

diabetes self-management across race/ethnicity and health literacy? Diabetes Care. 2006;29(4):823-829.

23. Wheeler ML, Dunbar SA, Jaacks LM, et al. Macronutrients, food

groups, and eating patterns in the management of diabetes: a

systematic review of the literature, 2010. Diabetes Care.

2012;35(2):434-445.

24. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Facts about physical

activity. 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/data/facts.

html. Accessed January 15, 2015.

25. Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive

validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med

Care. 1986;24(1):67-74.

26. Eakin EG, Reeves MM, Bull SS, Floyd S, Riley KM, Glasgow

RE. Validation of the Spanish-language version of the Chronic

Illness Resources Survey. Int J Behav Med. 2007;14(2):76-85.

27. Child ST, McKenzie TL, Arredondo EM, Elder JP, Martinez SM,

Ayala GX. Associations between park facilities, user demographics, and physical activity levels at San Diego County parks. J

Park Recreation Admin. 2014;32(4).

28. Ayala GX, Rogers M, Arredondo EM, et al. Away-from-home

food intake and risk for obesity: examining the influence of context. Obesity. 2008;16(5):1002-1008.

29. Selvin E, Coresh J, Brancati FL. The burden and treatment of

diabetes in elderly individuals in the US. Diabetes Care.

2006;29(11):2415-2419.

30. Farmer AJ, Perera R, Ward A, et al. Meta-analysis of individual

patient data in randomised trials of self monitoring of blood glucose in people with non-insulin treated type 2 diabetes. BMJ.

2012;344.

31. Malanda UL, Welschen L, Riphagen II, Dekker JM, Nijpels G,

Bot S. Self-monitoring of blood glucose in patients with type 2

diabetes mellitus who are not using insulin. Cochrane Database

Syst Rev. 2012;1.

32. Williams K, Bond M. The roles of self-efficacy, outcome expectancies and social support in the self-care behaviours of diabetics.

Psychol, Health Med. 2002;7(2):127-141.

33. Wen LK, Shepherd MD, Parchman ML. Family support, diet, and

exercise among older Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes.

Diabetes Educ. 2004;30(6):980-993.

34. Gleeson-Kreig J. Social support and physical activity in type 2

diabetes: a social-ecologic approach. Diabetes Educ. 2008;

34(6):1037-1044.

35. Ahia CL, Holt EW, Krousel-Wood M. Diabetes care and its association with glycosylated hemoglobin level. Am J Med Sci.

2014;347(3):245-247.

36. Shaw BA, Gallant MP, Riley-Jacome M, Spokane LS. Assessing

sources of support for diabetes self-care in urban and rural

underserved communities. J Community Health. 2006;31(5):

393-412.

37. Sherbourne CD, Hays RD, Ordway L, DiMatteo MR, Kravitz RL.

Antecedents of adherence to medical recommendations: results

from the Medical Outcomes Study. J Behav Med. 1992;15(5):447468.

38. Oftedal B, Bru E, Karlsen B. Social support as a motivator of

self-management among adults with type 2 diabetes. J Nurs

Healthcare Chronic Illness. 2011;3(1):12-22.

39. Fortmann AL, Gallo LC, Philis-Tsimikas A. Glycemic control

among Latinos with type 2 diabetes: the role of social-environmental support resources. Health Psychology. 2011;30(3):

251.

For reprints and permission queries, please visit SAGEs Web site at http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav.

Soto et al

Downloaded from tde.sagepub.com at Bobst Library, New York University on May 25, 2015

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Lovelylesh Gains Workout GuideDocumento40 pagineLovelylesh Gains Workout Guideyashaira acevedo100% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- 12 Week 100 200m Workouts PDFDocumento12 pagine12 Week 100 200m Workouts PDFCorrado De Simone91% (32)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Family Stories and The Life Course Across Time and Generations - FieseDocumento451 pagineFamily Stories and The Life Course Across Time and Generations - FieseNatalia Moc100% (1)

- SBH 2016Documento360 pagineSBH 2016Julia ChinyunaNessuna valutazione finora

- P.E. 8 Module 3Documento21 pagineP.E. 8 Module 3Glydel Mae Villamora - SaragenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Use of Glycated Haemoglobin (Hba1C) in The Diagnosis of Diabetes MellitusDocumento25 pagineUse of Glycated Haemoglobin (Hba1C) in The Diagnosis of Diabetes MellitusSiskawati Suparmin100% (1)

- (Ronald J. Angel, Laura Lein, Jane Henrici) Poor F PDFDocumento270 pagine(Ronald J. Angel, Laura Lein, Jane Henrici) Poor F PDFNatalia MocNessuna valutazione finora

- Denham, Manoogian y Schuster. 2007.managing Family Support and Dietary Routines Type 2 Diabetes in Rural Appalachian FamiliesDocumento17 pagineDenham, Manoogian y Schuster. 2007.managing Family Support and Dietary Routines Type 2 Diabetes in Rural Appalachian FamiliesNatalia MocNessuna valutazione finora

- Use of Glycated Haemoglobin (Hba1C) in The Diagnosis of Diabetes MellitusDocumento25 pagineUse of Glycated Haemoglobin (Hba1C) in The Diagnosis of Diabetes MellitusSiskawati Suparmin100% (1)

- García Et Al. 2015. Hierarchical Clusters in Families With Type 2 DiabetesDocumento8 pagineGarcía Et Al. 2015. Hierarchical Clusters in Families With Type 2 DiabetesNatalia MocNessuna valutazione finora

- Jimenezlopez 2014Documento13 pagineJimenezlopez 2014Natalia MocNessuna valutazione finora

- (Christopher G. Ellison, Robert A. Hummer) Religio PDFDocumento481 pagine(Christopher G. Ellison, Robert A. Hummer) Religio PDFNatalia MocNessuna valutazione finora

- Reutrakul Et Al. 2015. Relationships Among Sleep Timing, Sleep Duration and Glycemic Control in Type 2 Diabetes in ThailandDocumento9 pagineReutrakul Et Al. 2015. Relationships Among Sleep Timing, Sleep Duration and Glycemic Control in Type 2 Diabetes in ThailandNatalia MocNessuna valutazione finora

- Jones Et Al. 2014. Jones, McDonald, Hattersley & Shields. Effect of The Holiday Season in Patients With Diabetes Glycemia and Lipids Increase Postholiday, BDocumento3 pagineJones Et Al. 2014. Jones, McDonald, Hattersley & Shields. Effect of The Holiday Season in Patients With Diabetes Glycemia and Lipids Increase Postholiday, BNatalia MocNessuna valutazione finora

- Camara. 2015.poor Glycemic Control in Type 2 Diabetes in The South of The SaharaDocumento6 pagineCamara. 2015.poor Glycemic Control in Type 2 Diabetes in The South of The SaharaNatalia MocNessuna valutazione finora

- Thompson. 2014.occupations, Habits, and Routines Perspectives From Persons With DiabetesDocumento8 pagineThompson. 2014.occupations, Habits, and Routines Perspectives From Persons With DiabetesNatalia MocNessuna valutazione finora

- Wainstein Et Al. 2011. Jewish New Year Associated With Decreased Point of Care Glucose in Hospitalised Patient PopulationDocumento5 pagineWainstein Et Al. 2011. Jewish New Year Associated With Decreased Point of Care Glucose in Hospitalised Patient PopulationNatalia MocNessuna valutazione finora

- Mayberry y Osborn. 2012.family Support, Medication Adherence, and Glycemic Control Among Adults With Type 2 DiabetesDocumento7 pagineMayberry y Osborn. 2012.family Support, Medication Adherence, and Glycemic Control Among Adults With Type 2 DiabetesNatalia MocNessuna valutazione finora

- Yoon. 2012. The Role of Family Routines and Rituals in The Psychological Well Being of Emerging AdultsDocumento98 pagineYoon. 2012. The Role of Family Routines and Rituals in The Psychological Well Being of Emerging AdultsNatalia MocNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Create A Journal Article From A ThesisDocumento6 pagineHow To Create A Journal Article From A ThesisNatalia MocNessuna valutazione finora

- Fiese Et Al. 2002. A Review of 50 Years of Research On Naturally Occurring Family Routines and Rituals Cause For CelebrationDocumento10 pagineFiese Et Al. 2002. A Review of 50 Years of Research On Naturally Occurring Family Routines and Rituals Cause For CelebrationNatalia MocNessuna valutazione finora

- National Council On Family Relations and Wiley Are Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Family RelationsDocumento3 pagineNational Council On Family Relations and Wiley Are Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Family RelationsNatalia MocNessuna valutazione finora

- RutinasDocumento19 pagineRutinasNatalia MocNessuna valutazione finora

- Zisberg, Young, Schepp y Zysberg. 2007.a Concept Analysis of Routine Relevance To NursingDocumento12 pagineZisberg, Young, Schepp y Zysberg. 2007.a Concept Analysis of Routine Relevance To NursingNatalia MocNessuna valutazione finora

- Glycemic Control Rate of T2DM Outpatients in China: A Multi-Center SurveyDocumento7 pagineGlycemic Control Rate of T2DM Outpatients in China: A Multi-Center SurveyNatalia MocNessuna valutazione finora

- Stopford, Winkley y Ismail. 2013.social Support and Glycemic Control in Type 2 Diabetes A Systematic Review of Observational StudiesDocumento10 pagineStopford, Winkley y Ismail. 2013.social Support and Glycemic Control in Type 2 Diabetes A Systematic Review of Observational StudiesNatalia MocNessuna valutazione finora

- Kanjanawetang, Yunibhand, Chaiyawat, Wu y Denham. 2009.thai Family Health Routines Scale Development and Psychometric TestingDocumento15 pagineKanjanawetang, Yunibhand, Chaiyawat, Wu y Denham. 2009.thai Family Health Routines Scale Development and Psychometric TestingNatalia MocNessuna valutazione finora

- Harkness 1994Documento10 pagineHarkness 1994Natalia MocNessuna valutazione finora

- 10.0000@etd - Ohiolink.edu@generic B9A7336B0428Documento133 pagine10.0000@etd - Ohiolink.edu@generic B9A7336B0428Natalia MocNessuna valutazione finora

- Aprendiendo A AprenderDocumento8 pagineAprendiendo A AprenderNatalia MocNessuna valutazione finora

- The DevelopmentDocumento28 pagineThe DevelopmentSoulyogaNessuna valutazione finora

- Cohen's Kappa MethodDocumento27 pagineCohen's Kappa Methodshoba0811Nessuna valutazione finora

- Family Nursing ProcessDocumento12 pagineFamily Nursing ProcessChristine CornagoNessuna valutazione finora

- Nursing Care Plan For StrokeDocumento5 pagineNursing Care Plan For Strokerusseldabon24Nessuna valutazione finora

- Exercise For Fitness Study GuideDocumento4 pagineExercise For Fitness Study GuideYraNessuna valutazione finora

- JMDH 14 1977Documento10 pagineJMDH 14 1977Mariano PadillaNessuna valutazione finora

- TFN 2ND UeDocumento15 pagineTFN 2ND UeLorenz Jude CańeteNessuna valutazione finora

- How Is A Middle Range Nursing Theory Applicable To Your PracticeDocumento7 pagineHow Is A Middle Range Nursing Theory Applicable To Your PracticeSheila KorirNessuna valutazione finora

- Training Zone Calculations: Run Cycle SwimDocumento7 pagineTraining Zone Calculations: Run Cycle SwimMoreno LuponiNessuna valutazione finora

- Vi. SOAL PASDocumento6 pagineVi. SOAL PASMTs Al IstiqomahNessuna valutazione finora

- Weight ManagementDocumento50 pagineWeight Managementzia ullahNessuna valutazione finora

- Overweight RatesDocumento2 pagineOverweight RatesGiáng My PianistNessuna valutazione finora

- Individual Assignment 3 13 MarksDocumento2 pagineIndividual Assignment 3 13 MarksKazuraba KenNessuna valutazione finora

- Vertimax Phase 2 WorkoutDocumento1 paginaVertimax Phase 2 Workoutkbhtgq5t5rNessuna valutazione finora

- Luffy Workout Routine PDFDocumento10 pagineLuffy Workout Routine PDFTriistanNessuna valutazione finora

- (H.I.I.T) HIGH-Intensity Interval Training: Tabata Xercise: Pahfit 2Documento18 pagine(H.I.I.T) HIGH-Intensity Interval Training: Tabata Xercise: Pahfit 2ArianaNessuna valutazione finora

- TFN OremDocumento2 pagineTFN OremChristine QuejadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Week 2 DLP Physical FitnessDocumento12 pagineWeek 2 DLP Physical FitnessjingNessuna valutazione finora

- HCGives You Wings WorkoutDocumento1 paginaHCGives You Wings Workoutbadboyop101Nessuna valutazione finora

- EnglishDocumento23 pagineEnglishCarine TanNessuna valutazione finora

- The Big Squeeze LabDocumento3 pagineThe Big Squeeze Labjett deanNessuna valutazione finora

- Chronic Pain Clinic Referral Form Jpocsc: Fax: (604) 582-4591 PH: (604) 582-4587Documento2 pagineChronic Pain Clinic Referral Form Jpocsc: Fax: (604) 582-4591 PH: (604) 582-4587Muhammed SamiNessuna valutazione finora

- Action PlanDocumento3 pagineAction PlanKathrine Garcia-MendozaNessuna valutazione finora

- Yearly Planner Training Primary & Secondary 2023Documento5 pagineYearly Planner Training Primary & Secondary 2023Faradilah RaznieNessuna valutazione finora

- Muscle FictionDocumento2 pagineMuscle Fictionhollowtip0504Nessuna valutazione finora

- Family Case Study.Documento4 pagineFamily Case Study.sleep what100% (1)

- Fitt ProDocumento9 pagineFitt Proapi-308056028Nessuna valutazione finora

- PEH Q2 Long Quiz 1 (Performance Task 1)Documento8 paginePEH Q2 Long Quiz 1 (Performance Task 1)Lourince Æ SeguisabalNessuna valutazione finora