Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Person Perception and Personality Pathology

Caricato da

Jacobo riquelmeCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Person Perception and Personality Pathology

Caricato da

Jacobo riquelmeCopyright:

Formati disponibili

CURRENT DIRECTIONS IN PSYCHOLOGICAL S CIENCE

Person Perception and

Personality Pathology

Thomas F. Oltmanns1 and Eric Turkheimer2

1

Washington University in St. Louis and 2University of Virginia

ABSTRACTStudies

of person perception (peoples impressions and beliefs about others) have developed important

concepts and methods that can be used to help improve the

assessment of personality disorders. They may also inspire

advances in our knowledge of the nature and origins of these

conditions. Information collected from peers and other

types of informants is reliable and provides a perspective

that often differs substantially from that obtained using

questionnaires and interviews. For some purposes, this information is quite useful. Much remains to be learned about

the incremental validity (and potential biases) associated

with data from various kinds of informants.

KEYWORDSassessment; personality disorders; person

perception; self-knowledge

Personality disorders are enduring patterns of behavior and

emotion that bring a person into repeated conflict with others and

prevent the person from performing expected social and occupational roles. People with personality disorders often make

their own interpersonal problems worse because they are rigid

and inflexible, unable to adapt to social challenges. Nevertheless, they may not see themselves as being disturbed, attributing

their problems instead to the behavior of other people. Many

forms of personality disorder, such as paranoid, narcissistic,

antisocial, and histrionic personality disorder, are defined primarily in terms of problems that people create for others rather

than in terms of the persons own subjective distress (Westen &

Heim, 2003).

Studies of person perception (how people perceive other

people, especially their personality characteristics) raise challenging issues and interesting opportunities for the assessment

of personality disorders (Clark, 2007; Widiger & Samuel, 2005).

There is, at best, only a modest correlation between individuals

descriptions of themselves and descriptions of them provided by

others (Biesanz, West, & Millevoi, 2007; Watson, Hubbard, &

Address correspondence to Thomas F. Oltmanns, Department of

Psychology, Campus Box 1125, One Brookings Drive, Washington

University, St. Louis, MO 63130-4899; e-mail: toltmann@wustl.edu.

32

Weise, 2000). It is therefore surprising that most knowledge of

personality disorders is based on evidence obtained from selfreport measures (questionnaires and diagnostic interviews). The

person is asked to answer questions such as Are you stubborn

and set in your ways?, Do you behave in an arrogant and

haughty way?, and Is it easy for you to lie if it serves your

purpose? Data from these instruments should be supplemented

by other sources of information regarding personality, such

as informant reports, observations of behavior in structured situations, and life-outcome data. The goal of this article is to describe

evidence about the relations among, and relative merits of,

assessments of personality disorders based on self-report measures

and information provided by informants who know that person well.

Our research group has studied interpersonal perception of

pathological personality traits in two large samples of young

adultsapproximately 2,000 military recruits and 1,700 college freshmen (Oltmanns & Turkheimer, 2006). The participants

were identified and tested in groups. Military training groups

included between 27 and 53 recruits, and college dormitory

groups included between 12 and 22 students. Each group was

composed of previously unacquainted young adults who had

many opportunities to observe each others behavior after living

together in close proximity for a standard period of time (6 weeks

for the recruits and 5 to 7 months for the students). Although

these were not clinical samples of patients being treated for

mental disorders, they did include people with significant personality problems. Diagnostic interviews indicated that, consistent with data from other community samples, approximately

10% of our participants qualified for a diagnosis of at least one

personality disorder.

All participants in each group completed self-report questionnaires, and they also nominated members of their group who

exhibited specific features of personality disorders. Everyone

served as both a judge and a possible target. Serving as a judge

for each specific item, the participant rated only those people

whom he or she viewed as showing the characteristics in question. Exactly the same items were included in both the selfreport and peer-nomination scales. All were lay translations

of specific diagnostic features used to define personality disorders in the official psychiatric classification system. Examples

Copyright r 2009 Association for Psychological Science

Volume 18Number 1

Thomas F. Oltmanns and Eric Turkheimer

include: Is stuck up or high and mighty (narcissistic PD),

Needs to do such a perfect job that nothing ever gets finished

(obsessive-compulsive PD), and Has no close friends, other

than family members (schizoid PD).

This design allowed us to examine four issues regarding interpersonal perception: consensus, selfother agreement, accuracy, and metaperception (Funder, 1999; Kenny, 2004).

Consensus is concerned with whether different judges agree in

their perceptions of the target persons personality. Selfother

agreement involves the extent to which people view themselves

in the same ways they are described by other people. Accuracy

refers to the validity of self- and other judgments. In other words,

is either source of information related in a meaningful way

to outcomes in the persons life, such as social adjustment or

occupational impairment? Metaperception describes the extent

to which people are aware of the impressions that other people

have of them. In other words, regardless of my own description of

myself, am I aware of what others think of me?

CONSENSUS AMONG PEERS IS MODEST

Studies of person perception report acceptable levels of consensus among laypeople when making judgments of normal

personality traits, especially when ratings are aggregated across

a large number of judges (Funder, 1999; Vazire, 2006). Data from

our study indicate modest consensus among peers in judgments

of other peoples personality pathology. Reliability of composite

peer-based scoresaveraged across a number of judgeswas

good (Clifton, Turkheimer, & Oltmanns, 2005; Thomas, Turkheimer, & Oltmanns, 2003). Their judgments were presumably

based on opportunities they had had to observe each others

behavior, often in challenging situations, over a period of several

weeks. Peers developed meaningful perspectives on the personality problems of other group members, and they tended to

agree about which members exhibited those problems.

Previous studies indicate that the level of consensus among

judges varies as a function of many considerations, such as the

extent of acquaintance between judges and the target person

(Letzring, Wells, & Funder, 2006). Many decisions about personality disorders, including those made by clinicians, as well as

those made by family members, friends, and the peers in our

studies, are based on thoughtful deliberation following extended

observations of inconsistent, puzzling, annoying, and occasionally

disturbing behaviors. It is also clear, however, that some personality judgments about other people are formed quickly and without

conscious effort or reason (Ambady, Bernieri, & Richeson, 2000).

Data from our lab suggest that, on the basis of minimal information, observers can form reliable impressions of people

who qualify for diagnoses of various types of personality disorder. Untrained raters watched only the first 30 seconds of videotaped interviews with target persons from our study. Based

only on these thin slices of behavior, the raters generated reliable judgments regarding broad personality traits using the Five

Volume 18Number 1

Factor Model, a widely accepted system for describing personality. Higher levels of consensus were found for extraversion,

agreeableness, openness, and conscientiousness, while lower

agreement was found for neuroticism. The judges ratings were

also accurate in some ways. People who were otherwise unacquainted with our target persons detected the low extraversion of

individuals with features of schizoid and avoidant personality

disorders and the high extraversion of individuals with histrionic

personality features. They were also reliable in rating specific

features of personality disorders (such as Is stuck up or high

and mighty with regard to narcissistic personality disorder),

and these judgments were significantly correlated with more

extensive diagnostic information collected from the persons and

from their peers (Friedman, Oltmanns, & Turkheimer, 2007).

Perceptions of pathological personality traits also influenced

the extent to which the thin-slice raters liked the people they had

watched. They were less interested in meeting people with

schizoid and avoidant personality traits and were more interested in getting to know people who exhibited traits associated

with histrionic and narcissistic personality disorders. These

patterns suggest possible mechanisms that may maintain or

exacerbate personality difficulties. To the extent that people who

are avoidant create a negative first impression, they may become

even more anxious about their interactions with other people. On

the other hand, histrionic and narcissistic behaviors may be

perpetuated by the way in which they attract others, at least

temporarily. These traits may not become interpersonally disruptive until relationships become more intimate.

SELFOTHER AGREEMENT IS ALSO MODEST

One primary issue in our study involved the correspondence

between self-report and peer nominations for characteristic

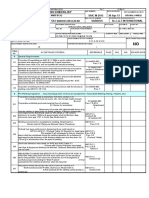

features of personality disorders. Table 1 presents results from

our sample of military recruits using scores based on a factor

analysis of self-report and peer-nomination data (Thomas et al.,

2003). The factors correspond closely to diagnostic categories

for personality disorders: histrionic-narcissistic, dependentavoidant, detachment (similar to schizoid), aggression-mistrust

(similar to paranoia), antisocial, obsessive-compulsive, and

schizotypal (an enduring pattern of discomfort with other people

coupled with peculiar thinking and behavior). The data show a

modest level of convergent and discriminant validity (i.e.,

measures of the same concept are more highly correlated with

each other than measures of different concepts) for peer- and

self-perception on these particular traits. Within-trait crossmethod correlations appear on the diagonal. In every case, the

within-trait cross-method correlation (e.g., between self-report

for antisocial personality features and peer nominations for

antisocial personality features) was higher than any of the crosstrait correlations. The highest correlations fell on the diagonal,

but they were also modest in size, suggesting disagreement

between the ways in which people described themselves and the

33

Personality Pathology

TABLE 1

Correlations Between Peer and Self-Report Scores for

Personality Pathology Factors in a Military Sample

Peer

Self

HN

DA

HN

DA

DET

AM

ANT

OC

STY

.22

.18

.08

.07

.17

.08

.07

.09

.30

.03

.10

.08

.00

.01

DET

.02

.07

.21

.04

.03

.03

.01

AM

.07

.08

.03

.29

.07

.08

.07

ANT

.01

.01

.19

.10

.30

.05

.03

OC

.07

.07

.03

.08

.12

.27

.02

STY

.07

.05

.07

.08

.04

.02

.24

Note. HN 5 Histrionic/Narcissistic; DA 5 Dependent/Avoidant; DET 5 Detachment; AM 5 Aggression/Mistrust; ANT 5 Antisocial; OC 5 Obsessive-Compulsive; STY 5 Schizotypal. Correlations can vary from 0 to 1.0, with 0 meaning that

there is no relationship between two variables and 1.0 meaning that there is a

perfect relationship. Positive correlations indicate that as one variable increases,

the other also increases. Correlations between .10 and .30 are often considered to

be small, and correlations between .30 and .50 are interpreted as being medium in

size. Reprinted from Factorial Structure of Pathological Personality Traits as

Evaluated by Peers, by C. Thomas, E. Turkheimer, & T.F. Oltmanns, 2003,

Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112, p. 8. Copyright 2003, American Psychological Association. Reprinted with permission.

ways in which they were described by their peers. These data and

the results of studies from other labs suggest that self-reports

provide a limited view of personality problems (Furr, Dougherty,

Marsh, & Matthias, 2007; Miller, Pilkonis, & Clifton, 2005).

The level of agreement between self-report and peer report is

fairly good and is actually no better or worse than the level of

agreement between any two specific peers. One advantage of

informant reports is that there are many possible sources.

Composite scores, averaged across several friends, family

members, or peers, are likely to be more reliable than a single

self-report score. But the most important issue is incremental

validity: Do peer reports add important information beyond that

which is provided in self-report measures?

METAPERCEPTIONS ARE NOT BASED EXCLUSIVELY

ON SELF-PERCEPTIONS

The fact that people do not always agree with others perceptions

of them does not necessarily imply that they are unaware of what

others think. They may simply hold a different view. The literature on metaperception for normal personality traits suggests

that people do, in fact, have some accurate, generalized

knowledge of what others think of them (Kenny, 1994).

Participants in our study were asked to anticipate the ways in

which most other members of their group would describe them.

These expected peer scores were highly correlated with the

participants own descriptions of themselves (i.e., What are you

really like?). People believe that others share the same view

that they hold of their own personality characteristics. On the

other hand, we also found that expected peer scores predicted

some variability in peer report over and above self-report for all

34

of the different forms of personality disorder (Oltmanns, Gleason, Klonsky, & Turkheimer, 2005). This finding suggests that

people do have at least some small amount of incremental

knowledge regarding how they are viewed by others. They are

sometimes aware of the fact that other people think they have

personality problems, but they usually dont tell you about it

unless you ask them.

INFORMANT REPORTS ARE ACCURATE FOR SOME

PROBLEMS

Perhaps the most important issue in the field of interpersonal

perception involves accuracy, or validity. Disagreement between

sources of information (self and informant) does not suggest that

one kind of measure is more valid than the other. The most important question is, which source of data is most useful, and for

what purpose? One relevant study examined self- and informant

reports of personality disorders in a follow-up study with depressed patients (Klein, 2003). Both self-report and informant

reports regarding personality disorders were associated with a

worse outcome in terms of depressed symptoms and global

functioning. However, informants reports of personality pathology were the most useful predictor of future social impairment.

Similar results have been found in our research with regard to

job success following successful completion of basic military

training (Fiedler, Oltmanns, & Turkheimer, 2004). All of the

recruits had enlisted to serve for a period of 4 years. At the time

of follow-up, we divided the recruits into two groups: (a) those

still engaged in active duty employment, and (b) those given an

early discharge from the military. Early discharge is typically

granted by a superior officer on an involuntary basis, and is most

often justified by repeated disciplinary problems, serious

interpersonal difficulties, or a poor performance record.

We conducted a survival analysis of time to failurethat is,

an analysis of the predictors of how much time it took recruits to

be discharged early. We used standard rank-based procedures

(using ordinal as opposed to interval data) to estimate the

univariate relations between self- and peer-report of the 10

personality disorders and early discharge from the military.

Results are shown in Figure 1, which illustrates the magnitude of

the relation between each disorder and risk for discharge. For all

of the disorders except obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, higher scores were associated with greater risk of early

discharge. The figure shows that in general, peer reports of

personality disorders were better predictors than self-reports

were. When we combined the self-report and peer-based information, using them together to identify recruits who were discharged early from the military, the best predictor variables were

peer scores for antisocial and borderline personality disorders.

These results point to several general conclusions. Both selfreport and peer nominations were able to identify meaningful

connections between personality problems and adjustment to

military life. Self-report measures emphasized features that

Volume 18Number 1

Thomas F. Oltmanns and Eric Turkheimer

Self-Report

Peer Nomination

Strength of Association

45

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

e

iv

ls

de

pu

en

om

ep

O

bs

es

si

ve

-C

Av

o

id

an

nt

tic

is

ci

ar

N

is

tri

er

rd

Bo

ss

lin

on

ic

l

oc

tis

An

ty

ia

pa

id

zo

hi

Sc

hi

zo

id

Sc

no

ra

Pa

Type of Personality Disorder Features

Fig. 1. Relative strength of self-report and peer report in predicting early separation from military

service, for 10 types of personality-disorder features. (Strength of association between self- and peernominated traits and risk for early termination is expressed as a chi-square test of the log-rank Wilcoxon.)

might be described as internalizing problems (subjective

distress and self-harm) while the peer-report data emphasized

externalizing problems (antisocial traits). Considered together,

the peer-nomination scores were more effective than the selfreport scales were in predicting occupational outcome. The

relative merits of self- and peer reports probably differ with regard to the measure of functioning or outcome that is being

predicted, and future research ought to focus on those comparisons across a wide range of constructs.

SUMMARY AND ISSUES FOR FURTHER

INVESTIGATION

Informants can provide reliable and valid information about an

individual that is largely independent of that obtained from the

persons own self-report. Correlations between self-report and

informant reports are consistently modest, and the independent

information provided by informants tells us something important

about personality problems. This conclusion is consistent with

the more general observation that personality disorders are

frequently defined and experienced in terms of interpersonal

conflict and problems in person perception. Although most investigators rely on self-report measures to assess personality

disorders, a more complete description of the person would be

obtained by also considering data from informants. The most

comprehensive approach would be one that assembled and in-

Volume 18Number 1

tegrated data from many different people, including the self, thus

reflecting the widest possible range of impressions of the target

persons behavior in different contexts.

Of course, it is difficult to collect data from a large number of

people who know the target person, and it is seldom possible to

contact people who are not selected by (and may not like) the

target person. Therefore, to whatever extent they are able to

gather data from informants, most researchers will rely on a

small number of informants chosen by the subject. Future

studies need to investigate these issues. How many informants

are needed in order to provide a useful perspective that complements the persons own description of himself or herself?

What kind of bias is introduced by various kinds of self-selected

informants (parents, spouses, friends)? How are data that these

people provide different from those that might be obtained from

informants who are not selected by the target person? And

perhaps most important, how does the validity of informant

reports compare to that of self-report measures when a broader

range of outcome measures is considered?

Longitudinal studies of person perception in the context of

specific relationships will also be important. Thin-slice studies

suggest that people with different kinds of personality problems

can create marked impressions (both positive and negative) on

others at the outset of a relationship. It will be interesting to learn

how these impressions affect the progression of the relationship

and how such perceptions may change over time.

35

Personality Pathology

Recommended Readings

Achenbach, T.M., Krukowski, R.A., Dumenci, L., & Ivanova, M.Y.

(2005). Assessment of adult psychopathology: Meta-analyses

and implications of cross-informant correlations. Psychological

Bulletin, 131, 361382. A thorough and critical review of issues

regarding limitations of self-report instruments for the purpose of

measuring psychopathology, across many different types of mental

disorder.

Klonsky, E.D., Oltmanns, T.F., & Turkheimer, E. (2002). Informant

reports of personality disorder: Relation to self-reports and future

research directions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 9,

300311. A summary of research evidence from studies that have

specifically compared self- and informant reports of personality

disorders regarding the same target persons.

Wilson, T.D., & Dunn, E.W. (2004). Self knowledge: Its limits, value,

and potential for improvement. Annual Review of Psychology, 55,

493518. A comprehensive summary of evidence regarding the

ability of individuals to understand what others think of them.

REFERENCES

Ambady, N., Bernieri, F.J., & Richeson, J.A. (2000). Toward a histology

of social behavior: Judgmental accuracy from thin slices of the

behavioral stream. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology,

32, 201271.

Biesanz, J.C., West, S.G., & Millevoi, A. (2007). What do you learn

about someone over time? The relationship between length of

acquaintance and consensus and self-other agreement in judgments of personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

92, 119135.

Clark, L.A. (2007). Assessment and diagnosis of personality disorder:

Perennial issues and an emerging reconceptualization. Annual

Review of Psychology, 58, 227257.

Clifton, A., Turkheimer, E., & Oltmanns, T.F. (2005). Self and peer

perspectives on pathological personality traits and interpersonal

problems. Psychological Assessment, 17, 123131.

Fiedler, E.R., Oltmanns, T.F., & Turkheimer, E. (2004). Traits associated with personality disorders and adjustment to military life:

Predictive validity of self and peer reports. Military Medicine, 169,

207211.

Friedman, J.N.W., Oltmanns, T.F., & Turkheimer, E. (2007). Interpersonal perception and personality disorders: Utilization of a thin

slice approach. Journal of Research in Personality, 41, 667688.

36

Funder, D.C. (1999). Personality judgment: A realistic approach to

person perception. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Furr, R.M., Dougherty, D.M., Marsh, D.M., & Mathias, D.W. (2007).

Personality judgment and personality pathology: Self-other

agreement in adolescents with conduct disorder. Journal of

Personality, 75, 629662.

Kenny, D.A. (1994). Interpersonal perception: A social relations analysis.

New York: Guilford.

Kenny, D.A. (2004). PERSON: A general model of interpersonal

perception. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 8, 265

280.

Klein, D.N. (2003). Patients versus informants reports of personality

disorders in predicting 7 1/2-year outcome in outpatients with

depressive disorders. Psychological Assessment, 15, 216222.

Letzring, T.D., Wells, S.M., & Funder, D.C. (2006). Information

quantity and quality affect the realistic accuracy of personality

judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91, 111

123.

Miller, J.D., Pilkonis, P.A., & Clifton, A. (2005). Self- and other-reports

of traits from the five-factor model: Relations to personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders, 19, 400419.

Oltmanns, T.F., Gleason, M.E.J., Klonsky, E.D., & Turkheimer, E.

(2005). Meta-perception for pathological personality traits: Do we

know when others think that we are difficult? Consciousness and

Cognition, 14, 739751.

Oltmanns, T.F., & Turkheimer, E. (2006). Perceptions of self and others

regarding pathological personality traits. In R.F. Krueger & J.L.

Tackett (Eds.), Personality and psychopathology (pp. 71111).

New York: Guilford.

Thomas, C., Turkheimer, E., & Oltmanns, T.F. (2003). Factorial structure of pathological personality traits as evaluated by peers.

Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112, 112.

Vazire, S. (2006). Informant reports: A cheap, fast, and easy method for

personality assessment. Journal of Research in Personality, 40,

472481.

Watson, D., Hubbard, B., & Weise, D. (2000). Selfother agreement in

personality and affectivity: The role of acquaintanceship, trait

visibility, and assumed similarity. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 78, 546558.

Westen, D., & Heim, A.K. (2003). Disturbances of self and identity in

personality disorders. In M.R. Leary & J.P. Tangney (Eds),

Handbook of self and identity (pp. 643664). New York: Guilford.

Widiger, T.A., & Samuel, D.B. (2005). Evidence-based assessment

of personality disorders. Psychological Assessment, 17, 278

287.

Volume 18Number 1

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Black BookDocumento28 pagineBlack Bookshubham50% (2)

- Dumitrascu 2007 - Rorschach Comprehensive System Data For A Sample of 111 Adults From RomaniaDocumento7 pagineDumitrascu 2007 - Rorschach Comprehensive System Data For A Sample of 111 Adults From RomaniaJacobo riquelmeNessuna valutazione finora

- KINGS Merovingians and VisigothsDocumento1 paginaKINGS Merovingians and VisigothsJacobo riquelmeNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is Organization TheoryDocumento24 pagineWhat Is Organization TheoryMohsen JozaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Why Narcissists Are Unwilling To Apologize The Role of Empathy and Guilt-Leunissen2017Documento19 pagineWhy Narcissists Are Unwilling To Apologize The Role of Empathy and Guilt-Leunissen2017Jacobo riquelme100% (1)

- Iranian Normative Reference DataDocumento12 pagineIranian Normative Reference DataJacobo riquelmeNessuna valutazione finora

- ElvishDocumento16 pagineElvishRyan AlexanderNessuna valutazione finora

- IRS Congress 1999Documento8 pagineIRS Congress 1999Jacobo riquelmeNessuna valutazione finora

- Heraldry of The DragonDocumento2 pagineHeraldry of The DragonJacobo riquelmeNessuna valutazione finora

- IRS Congress Boston 1996Documento6 pagineIRS Congress Boston 1996Jacobo riquelmeNessuna valutazione finora

- Moola Mantra Lyrics ChordsDocumento1 paginaMoola Mantra Lyrics ChordsRexinald Bannerington0% (1)

- Shopping Religion and The Sacred BuyosphereDocumento10 pagineShopping Religion and The Sacred BuyosphereJacobo riquelmeNessuna valutazione finora

- Organizational EthnographyDocumento19 pagineOrganizational EthnographyJacobo riquelmeNessuna valutazione finora

- The Races of The Old WorldDocumento545 pagineThe Races of The Old WorldJacobo riquelmeNessuna valutazione finora

- Surfing Fairy Tale-01Documento3 pagineSurfing Fairy Tale-01Jacobo riquelmeNessuna valutazione finora

- The Human Relation With Nature and Technological NatureDocumento6 pagineThe Human Relation With Nature and Technological NatureKristine Joy Mole-RellonNessuna valutazione finora

- Fall of The City of Wolves A Celtic Chariot BurialDocumento11 pagineFall of The City of Wolves A Celtic Chariot BurialJacobo riquelmeNessuna valutazione finora

- IRS Congress 1993Documento2 pagineIRS Congress 1993Jacobo riquelmeNessuna valutazione finora

- Birds Be Safe: Can A Novel Cat Collar Reduce Avian Mortality by Domestic Cats (Felis Catus) ?Documento8 pagineBirds Be Safe: Can A Novel Cat Collar Reduce Avian Mortality by Domestic Cats (Felis Catus) ?Jacobo riquelmeNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Constraints On The Direct PerceptionDocumento15 pagineSocial Constraints On The Direct PerceptionJacobo riquelmeNessuna valutazione finora

- Does Perfectionism Predict Depression AnxietyDocumento8 pagineDoes Perfectionism Predict Depression AnxietyJacobo riquelmeNessuna valutazione finora

- An Affective Model of Action Selection For Virtual HumansDocumento4 pagineAn Affective Model of Action Selection For Virtual HumansJacobo riquelmeNessuna valutazione finora

- Stability and Change in Personality DisorderDocumento5 pagineStability and Change in Personality DisorderJacobo riquelmeNessuna valutazione finora

- The New Person-Specific Paradigm in PsychologyDocumento6 pagineThe New Person-Specific Paradigm in PsychologyJacobo riquelmeNessuna valutazione finora

- Ten Lies of Ethnography Moral DilemmasDocumento29 pagineTen Lies of Ethnography Moral DilemmasJacobo riquelmeNessuna valutazione finora

- Basic Human Values: Inter-Value Structure in MemoryDocumento8 pagineBasic Human Values: Inter-Value Structure in MemoryJacobo riquelmeNessuna valutazione finora

- Triple Helix Networks in A Multicultural ContextDocumento22 pagineTriple Helix Networks in A Multicultural ContextJacobo riquelmeNessuna valutazione finora

- Metacognition in Humans and AnimalsDocumento5 pagineMetacognition in Humans and AnimalsJacobo riquelmeNessuna valutazione finora

- What Are We Measuring? Convergence of Leadership With Interpersonal and Non-Interpersonal PersonalityDocumento16 pagineWhat Are We Measuring? Convergence of Leadership With Interpersonal and Non-Interpersonal PersonalityJacobo riquelmeNessuna valutazione finora

- Enhancing Customer Service and Organizational Learning Through Qualitative ResearchDocumento9 pagineEnhancing Customer Service and Organizational Learning Through Qualitative ResearchJacobo riquelmeNessuna valutazione finora

- CNS Manual Vol III Version 2.0Documento54 pagineCNS Manual Vol III Version 2.0rono9796Nessuna valutazione finora

- The April Fair in Seville: Word FormationDocumento2 pagineThe April Fair in Seville: Word FormationДархан МакыжанNessuna valutazione finora

- To The Owner / President / CeoDocumento2 pagineTo The Owner / President / CeoChriestal SorianoNessuna valutazione finora

- Spine Beam - SCHEME 4Documento28 pagineSpine Beam - SCHEME 4Edi ObrayanNessuna valutazione finora

- Fortigate Fortiwifi 40F Series: Data SheetDocumento6 pagineFortigate Fortiwifi 40F Series: Data SheetDiego Carrasco DíazNessuna valutazione finora

- Immovable Sale-Purchase (Land) ContractDocumento6 pagineImmovable Sale-Purchase (Land) ContractMeta GoNessuna valutazione finora

- Invoice Acs # 18 TDH Dan Rof - Maret - 2021Documento101 pagineInvoice Acs # 18 TDH Dan Rof - Maret - 2021Rafi RaziqNessuna valutazione finora

- For Email Daily Thermetrics TSTC Product BrochureDocumento5 pagineFor Email Daily Thermetrics TSTC Product BrochureIlkuNessuna valutazione finora

- Sena BrochureDocumento5 pagineSena BrochureNICOLAS GUERRERO ARANGONessuna valutazione finora

- Media SchedulingDocumento4 pagineMedia SchedulingShreyansh PriyamNessuna valutazione finora

- Tax Accounting Jones CH 4 HW SolutionsDocumento7 pagineTax Accounting Jones CH 4 HW SolutionsLolaLaTraileraNessuna valutazione finora

- 11 TR DSU - CarrierDocumento1 pagina11 TR DSU - Carriercalvin.bloodaxe4478100% (1)

- Brazilian Mineral Bottled WaterDocumento11 pagineBrazilian Mineral Bottled WaterEdison OchiengNessuna valutazione finora

- 14 CE Chapter 14 - Developing Pricing StrategiesDocumento34 pagine14 CE Chapter 14 - Developing Pricing StrategiesAsha JaylalNessuna valutazione finora

- Learner Guide HDB Resale Procedure and Financial Plan - V2Documento0 pagineLearner Guide HDB Resale Procedure and Financial Plan - V2wangks1980Nessuna valutazione finora

- Industrial Management: Teaching Scheme: Examination SchemeDocumento2 pagineIndustrial Management: Teaching Scheme: Examination SchemeJeet AmarsedaNessuna valutazione finora

- Saic-M-2012 Rev 7 StructureDocumento6 pagineSaic-M-2012 Rev 7 StructuremohamedqcNessuna valutazione finora

- Gowtham Kumar Chitturi - HRMS Technical - 6 YrsDocumento4 pagineGowtham Kumar Chitturi - HRMS Technical - 6 YrsAnuNessuna valutazione finora

- Dreamfoil Creations & Nemeth DesignsDocumento22 pagineDreamfoil Creations & Nemeth DesignsManoel ValentimNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter03 - How To Retrieve Data From A Single TableDocumento35 pagineChapter03 - How To Retrieve Data From A Single TableGML KillNessuna valutazione finora

- BS en 118-2013-11Documento22 pagineBS en 118-2013-11Abey VettoorNessuna valutazione finora

- Spa ClaimsDocumento1 paginaSpa ClaimsJosephine Berces100% (1)

- Annisha Jain (Reporting Manager - Rudrakshi Kumar)Documento1 paginaAnnisha Jain (Reporting Manager - Rudrakshi Kumar)Ruchi AgarwallNessuna valutazione finora

- Expected MCQs CompressedDocumento31 pagineExpected MCQs CompressedAdithya kesavNessuna valutazione finora

- PRELEC 1 Updates in Managerial Accounting Notes PDFDocumento6 paginePRELEC 1 Updates in Managerial Accounting Notes PDFRaichele FranciscoNessuna valutazione finora

- Math 1 6Documento45 pagineMath 1 6Dhamar Hanania Ashari100% (1)

- 7373 16038 1 PBDocumento11 pagine7373 16038 1 PBkedairekarl UNHASNessuna valutazione finora

- Jainithesh - Docx CorrectedDocumento54 pagineJainithesh - Docx CorrectedBala MuruganNessuna valutazione finora

- Module 5 - Multimedia Storage DevicesDocumento10 pagineModule 5 - Multimedia Storage Devicesjussan roaringNessuna valutazione finora