Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Implicit Leadership Theories-Offermann

Caricato da

GloryCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Implicit Leadership Theories-Offermann

Caricato da

GloryCopyright:

Formati disponibili

IMPLICIT LEADERSHIP THEORIES:

CONTENT, STRUCTURE,

AND GENERALIZABILITY

Lynn R. Offermann*

George Washington

University

John K. Kennedy, Jr.

Management

Decision

Systems

Philip W. Wirtz

George Washington

University

Although recent research has clearly demonstrated

the effects of peoples naive conceptions,

or

implicit theories, of leadership (ILTs) on leader ratings, there has been a lack of attention to the

content of such theories and whether there is systematic variation of ILTs across leader stimuli and

perceiver characteristics,

The current research assessed the content and factor structure variation of

ILTs for male and female perceivers (separately and combined) across three stimuli: leaders, effective

leaders, and supervisors.

Results suggest eight distinct factors of 1LTs (Sensitivity, Dedication,

Tyranny, Charisma, Attractiveness,

Masculinity,

Intelligence, and Strength) that remain relatively

stable across both perceiver sex and stimuli. Implicit theories for leaders and effective leaders were

typically more favorable than for supervisors. These findings suggest that implicit theories of leadership

may vary in systematic ways, and underscore the importance of reaching beyond mere recognition

of the existence of such theories toward an understanding

of variations in both the content and the

structure of the implicit ways that people view leaders.

Implicit theories of leadership (ILTs) have received increasing attention in recent years

as a means of understanding

leader attributions

and perceptions (e.g., Lord, Foti, &

DeVader, 1984) as well as a source of error in the measurement

of leader behavior

*

Direct all correspondence

to: Lynn R. Offermann,

Department

University, 2125 Cl St., N.W., Washington,

D.C. 20052.

Leadership Quarterly, S(l), 43-58.

Copyright @ 1994 by JAI Press Inc.

All rights of reproduction

in any form reserved.

ISSN: 1048-9843

of Psychology,

George

Washington

44

LEADERSHIP

QUARTERLY

Vol. 5 No. 1 1994

(e.g., Eden & Leviatan,

1975; Gioia & Sims, 1985). Although psychologists

have

difficulty in agreeing on what leadership really is, the general public seems to have little

trouble with the term. Individuals possess their own naive, implicit theories of leadership

and are readily willing to determine

their boundaries

and characteristics.

For

psychologists

lacking accepted definitions

of constructs on which to base explicit

theories of leadership, implicit theories can assist in providing a framework for the

development

of explicit theories. The present study uses a cognitive categorization

perspective to determine the content and structure of ILTs as well as to assess their

generalizability

across different targets and perceivers.

Based on the classic work of Eleanor Rosch (1978) on cognitive categorization,

Lord

and his associates (e.g., Lord, Foti, & DeVader, 1984; Lord, Foti, & Phillips, 1982)

have developed a theory of leadership categorization.

They maintain that implicit

theories of leadership reflect the structure and content of cognitive categories used

to distinguish

leaders from nonleaders.

According to this model, leadership is a

cognitive category in memory, organized hierarchically,

like all other categories, into

three levels. At the highest, most general level, called the superordinate

level, the

perceiver

makes a simple dichotomous

distinction

of leader or nonleader.

Theoretically,

there should be few characteristics that characterize all leaders, and very

little overlap between leaders and nonleaders. At the level below, the basic level, Lord

proposes that perceivers classify stimulus persons into one of eleven different types

of leader based on their setting, such as business leader, sports leader, media leader,

and so forth. These categorizations

are made by comparing the stimulus person with

the best example

of the category,

the category

prototype.

Such basic-level

categorizations

are believed to be the most important

level in that they convey the

most information

and typically reflect the names used to identify objects (Mervis &

Rosch, 1981). Thus, small red edible objects tend to be identified as apples(a basiclevel designation)

rather than fruit (a superordinate

term). The lowest and most

specific level of categorization

is the subordinate,

where apples could be broken down

into variants such as Macintosh or Rome Beauty.

But what of the leaders most people work with-their

supervisors? Unlike the

superordinate

term leader, the term supervisor likely reflects the basic level of

categorization,

akin to Lords business leader (Lord, Foti, & DeVader, 1984). Yet

the term supervisor also connotes a certain type of interpersonal relationship between

people in a way that the more generic, setting-oriented

term business leader does not,

and reflects the more common term people use for their immediate hierarchical superior.

If a basic-level category, supervisor would be expected to be richer in detail and less

inclusive than its superordinate

leader.l Because supervisors are typically studied as

subjects in leadership research, it is important

to examine the commonalities

and

differences between perceptions of leaders and supervisors.

In addition to potential categorical distinctions

between leaders and supervisors,

cognitive research in leadership argues strongly for the importance

of perceived

effectiveness on leader perceptions and evaluations. For example, Foti, Fraser, and Lord

(1982) found differences between ratings of political leaders and effective political

leaders, with positive items being rated as more prototypic of effective political leaders

than of political leaders in general. Rush, Thomas, and Lord (1977) also found

differences between ratings of effective and ineffective leaders. Based on these findings,

Implicit Leadership Theories

45

determining perceptions of effective leaders, and whether they differ from leaders,

would also be instructive.

Separate examination

of ILTs by stimulus targets such as leader, effective leader,

and supervisor, can answer two questions, one dealing with the issue of factor stability

across stimulus objects and the other with differences in levels of rating within a

particular stimulus object across different groups of perceivers. The first question

addresses the commonality

of characteristics used to describe leaders, effective leaders,

and supervisors. Although researchers have typically made the tacit assumption

that

factor structure does not vary significantly as a function of stimulus target (as evidenced

by a common willingness to transpose the terms leader and supervisor), there are reasons

to question this assumption

(Schneider,

1973). Correlations

among traits have been

shown to differ both as a function of stimulus person and relevance of trait (Koltuv,

1962). In the case of leadership stimuli, it is possible, for example, that raters see

characteristics

of sensitivity

and dedication

as descriptive

of both leaders and

supervisors, but positively related in leaders and negatively related in supervisors (or

vice versa).

The questions of factor structure differences across raters highlights the importance

of considering perceiver characteristics as well as stimulus characteristics in ILTs. Bieri

et al. (1966) and Goldstein and Blackman (1978) argue that there are systematic,

measurable differences in peoples implicit personality theories. Borman (1987) makes

a similar claim about implicit theories of subordinate

performance.

Peoples implicit

theories do not simply appear, fully formed, out of nowhere. Rather, they are generated

and refined over time as a result of peoples experiences

with actual leaders or

descriptions of leaders. Given that people have different exposure to and experiences

with leaders, there may be interesting and important differences in their implicit theories.

Because sex is a variable that may be reflective of differences in socialization history

and experiences

with leaders, it is possible that men and women structure their

perceptions of leaders differently. For example, Ayman (1993) suggests that respondent

sex may affect expectations

of leaders. Yet, previous research studies with ILTs have

typically collapsed male and female responses under untested assumptions of similarity.

We propose to test the assumption

of similar factor structures for male and female

perceivers.

In addition to understanding

the differences between perceptions of leaders, effective

leaders, and supervisors, information

on the content of ILTs may advance knowledge

in two ways. First, the content of ILTs may help us to better understand and ultimately

predict their effect on ratings of leader behavior. Second, and most importantly,

leadership researchers

may find that certain aspects of leadership are commonly

understood or inferred (as indicated by their presence in ILTs) that are not taken into

account in current theories and models of leadership. The study of implicit theories

can provide clues that will help in the development

of explicit theories to understand

the phenomenon

called leadership.

Sternberg (1985) has employed just such an approach to differentiate the concepts

of intelligence, creativity, and wisdom. His results indicate that people have well-defined

implicit theories of these three constructs and that they use them in their ratings of

both themselves and others. Furthermore,

Sternbergs results illustrate both the overlaps

and omissions between explicit theory and practice and laypersons conceptions.

For

46

LEADERSHIP

QUARTERLY

Vol. 5 No. 1 1994

example, peoples conceptions

of intelligence were shown to overlap but go beyond

skills measured by traditional intelligence tests, with laypersons including more practical

aspects of intelligence such as the ability to apply intelligence in worldly settings, to

balance information,

and to be goal-oriented,

in addition to standard reasoning,

vocabulary, and problem solving. Subsequent work by Sternberg (1988) has built on

these results by trying to incorporate

such domains

of practical intelligence

as

represented by laypersons implicit theories into a new explicit theory of intelligence.

Our approach with leaders, effective leaders, and supervisors parallels Sternbergs.

It is based on the cognitive categorization

approach, yet extends it in several important

ways. The traditional

approach to eliciting implicit theories asks people to generate

lists of characteristics in response to a single cue (e.g., leader). Indeed, we begin this

way as well. Others then have used these lists with the tacit assumption

that

characteristics

not generated spontaneously

are not present in the persons implicit

theory. However, while the spontaneously

generated items may reflect the characteristics

most salient at the time and perhaps, though arguably, the most central to the implicit

theory, certain characteristics of the implicit theory may still exist without spontaneously

surfacing, due to poor memory search or lack of involvement in the procedures. Yet,

if asked whether an ungenerated characteristic is prototypic of a target, individuals could

easily identify whether or not the characteristic fits their implicit theory.

The notion that implicit theories can contain far more than their spontaneously

expressed content is similar to the well-documented

finding in memory research that

recognition

memory results in retrieval of information

that might not be available

through recall (e.g., Klatzky, 1980). That is, people typically recognize items as fitting

or not fitting a particular set with far greater accuracy than they can recall them. In

a similar vein, the content of ILTs may far exceed the content that surfaces in

spontaneous

production

sessions. Thus, our approach begins with individual

item

generation,

but then combines the listed characteristics

of numerous individuals

to

produce an inclusive, collective list. This list of attributes can then be given to other

people who are asked to indicate which, if any, of the items are characteristic,

a

recognition task functioning here to produce prototypicality

ratings. Past research has

shown that items rated most typical of a target are the same items that are most often

supplied through open-ended questions (Mervis, Catlin, & Rosch, 1976).

These prototypicality

ratings can not only reveal the content of ILTs and the degree

of shared expectations that go beyond only the most salient, but they also allow for

the application of more powerful statistical techniques to understand them. One such

technique is factor analysis. In past attempts to maintain the valuable idiosyncrasies

of individual

perceptions,

the ability to produce useful summaries

of common

perceptions may have been lost. While the individual approach has greatly increased

our knowledge of ILT processes, there is a need to move beyond idiosyncratic

perceptions and into collective perceptions.

For example, in response to the cue of

leader one person may spontaneously

produce dependable

while another may

respond with reliable. While semantically

distinct, in terms of expectations

about

leadership, they convey the same message. Thus, our approach statistically reduces

individually generated prototypical characteristics into classes or factors that represent

collectively held expectations while still allowing individuals to express unique patterns

in their acceptance or endorsement of factors. These collective expectations, rather than

Implicit Leadership Theories

47

their individually held subcomponents,

may hold the most practical promise for leaders

in understanding

what their subordinates

as a group expect of them.

The present study examines both the content of ILTs and whether that content differs

as a function of characteristics of the stimulus target (leader, effective leader, supervisor)

and of the perceivers sex. It was hypothesized

that the factor structure of ILTs

themselves differ across stimulus conditions

and/or rater sex, and that differences

between the prototypicality

ratings of different leader targets would be found. In keeping

with past research, effective leaders were expected to receive higher ratings than leaders

or supervisors.

METHOD

AND RESULTS

The current research was carried out in five stages. Using undergraduate

samples, the

first stage consisted of generating a pool of items for our test instrument;

the second

attempted to identify the underlying factor structure of implicit theories of leadership;

the third focused on verifying the item content validity of the resulting factors; and

the fourth tested the research hypotheses. As a test of generalizability,

the fifth stage

involved the administration

of the instrument developed to a sample of working adults

for further validation.

Item Generation

Sample

The sample for item development

consisted

of 192 student volunteers

from

undergraduate

psychology courses at two large eastern universities. A questionnaire

was administered

during regular class periods, and required approximately

5 minutes

to complete.

Procedure

Respondents

(n = 115) were provided with a sheet of paper with instructions

and

25 blank lines and were asked to list up to 25 traits or characteristics

of a leader. No

definition of the term leader was provided in the instructions; subjects with questions

on this issue were instructed to use whatever definition was meaningful to them. Using

the same procedure, 77 participants listed traits associated with the term supervisor.

Results

Working first with the responses to the term leader, a total of 455 unique items

were obtained. The frequency with which each item was nominated was then computed.

Those items that were clearly behaviors (e.g., gives orders), and those items that were

only nominated

once or twice (e.g., religious) were deleted. Several items which were

clearly synonyms (e.g., funny-humorous)

were combined in order to reduce the number

of items to a reasonable size. On this basis, a pool of 160 items was retained.

Comparison

of our resulting items with Lord, Foti, and DeVaders (1984) attributes

generated to basic-level leader categories showed that over half of their 59 items were

represented exactly in our 160. As would be expected, these items had high family

resemblance scores (thus represented multiple categories of basic-level leaders). Some

48

LEADERSHIP

QUARTERLY

Vol. 5 No. 1 1994

of Lords attributes were represented by synonyms or multiple items on our scale (e.g.,

Lords verbal skills could be represented in our items by articulate, good

communicator, and eloquent). Items found by Lord but unrepresented in our item pool

were those with low family resemblance scores, indicating relevance to particular basiclevel leader domains rather than multiple leader categories (e.g., minority and patriotic).

This absence in our item pool would be expected given the items probable relevance

to certain types of leaders (i.e., political, minority, or military leaders) rather than leaders

in general.

Responses to the term supervisor were then compared to those of leader. Since

the superordinate term 1eadershould theoretically contain more items than the basiclevel term supervisor, our particular concern was to check on whether there were

items generated by the supervisor cue that were not reflected in the 160 items selected

for leader. The most typical supervisor responses were well reflected in the pool

of 160 items, either as elicited or by clear synonyms or by their opposite, as in patient

(generated to leader) and impatient (generated to supervisor?. There was one notable

exception-30 respondents generated the term leader to the supervisorcue, whereas

respondents to leader naturally did not repeat the cue as a response. In order to use

the same instrument for the different stimulus categories, which included leader, the

term leader was not used as an item in the final questionnaire, Thus, the 160 items

originally generated were retained. Based on our data from terms elicited by

supervisor, we believe that these 160 items included perceptions of supervisors as well

as leaders.

Factor Identification

The subjects for this phase were 763 undergraduate volunteers enrolled in

introductory psychology courses at the same two universities. Subjects received course

credit for their participation.

The 160 trait items were combined in random order into a single measure with lopoint response scales indicating the extent to which each trait was considered

characteristic of a stimulus person, where 1 was not at all characteristic and 10 was

extremely characteristic. Using this scale, subjects were asked to indicate how

characteristic each of the trait items was for one of three different stimulus persons:

either a leader, an effective leader, or a supervisor. Again, no explicit definitions of

the terms were provided. Respondents were also asked to indicate their sex. Subjects

were run in large groups of approximately 100 and were randomly assigned to one

of the stimulus person conditions. They were allowed to complete the ratings at their

own pace. Subjects who left more than 10 of the 160 items blank were omitted from

the analysis. Means were substituted for any blank items for the remaining subjects.

Complete scale data were obtained from 686 subjects (267 males, 379 females, 40 of

unknown sex).

49

implicit Leadership Theories

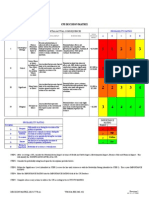

Table 1

Factor Names, Sample Items, and Reliabilities

Leadership Theory Factors

Factor Names/

Number of Items

Sample Items

Sensitivity

Sympathetic,

(10)

Dedication

Tyranny

(10)

(10)

Charisma

Domineering,

(10)

Attractiveness

Dedicated,

Charismatic,

(5)

Attractive,

Reliability

sensitive, compassionate,

disciplined,

inspiring,

Male, masculine

Intelligence

(6)

Intelligent,

(4)

Strong,

pushy, manipulative

.90

involved,

dynamic

26

.78

tall

.88

clever, knowledgeable,

forceful,

.94

.90

classy, well-dressed,

(2)

understanding

hard-working

prepared,

power-hungry,

Masculinity

Strength

of Implicit

bold, powerful

wise

.85

.74

Results

In order to capture as much of the total variation in the original set of 160 items

as possible, subject ratings were submitted to principal components

factor analysis

rotated to a varimax solution. Initial factor analyses were performed separately for each

of the three stimulus objects. A parallel analysis was run combining the data from the

three targets into a single merged file. Since examination

of the three separate and single

combined solution revealed no differences in high-loading items across stimulus type,

results of the combined analysis are subsequently

reported below. Six interpretable

factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.00 were obtained and were identified as indicating

dimensions

measuring Sensitivity, Dedication,

Tyranny, Charisma, Intelligence,

and

Attractiveness.

Exploratory

analyses of the data conducted separately for male and

female respondents suggested the presence of an additional meaningful factor measuring

Strength and that the Attractiveness

factor should be split into two separate factors

(one consisting of items related to gender and the other consisting of items more clearly

reflecting

attractiveness).

In order not to prematurely

eliminate

any potential

dimensions of peoples implicit theories of leadership, the eight factors were tentatively

retained for further analysis.

The first four factors were composed of a large number of items (20 or more items

with factor loadings greater than .40). In these instances, the 10 items with the highest

loadings on the factor were considered to comprise the factor. For the smaller factors,

all items with loadings greater than .40 were used to name the factor. Using these criteria,

57 items representing eight factors were retained from the initial 160. Table 1 presents

the names, number of items, some representative

items, and the coefficient alphas for

each of the eight factors.

50

LEADERSHIP

QUARTERLY

Vol. 5 No. 1 1994

Content Validation of Factors

Subjects

The 44 subjects (21 males, 23 females) for this phase of the study were introductory

psychology students. All subjects were native English speakers and received course credit

for their participation.

Procedure

Descriptive definitions of the eight implicit leadership theory factors identified in the

previous section were derived by the consensus of six subject matter experts. Each of

the 57 trait items comprising the factors was put on an individual card. Subjects were

run in groups of four but completed the task individually. The task consisted of sorting

each of the 57 trait cards into the factor definition considered most appropriate.

No

definitions of the trait adjectives were provided. Subjects completed the task at their

own pace. After all of the items had been assigned to factors, subjects were given an

opportunity

to look back over their work and make any changes that seemed

appropriate. The subjects were then debriefed as to the purpose of the study.

Results

The data were analyzed using a modified version of the procedure employed by

Hinkin and Schriesheim (1986). Data were aggregated to indicate the relative frequency

with which each trait item was assigned to each of the factor definitions. An item was

considered to be a useful representation

of a particular dimension if 70% of the subjects

assigned it to the factor it was intended to represent. Forty-one of the 57 items exceeded

this criterion. Because the trait-sorting task involved multiple judgments across multiple

raters, a measure of the extent to which raters agreed that certain groups of traits

belonged within each of the eight dimensions was indicated (Tinsley & Weiss, 1975).

Fleisss (1971) modified version of Cohens Kappa was employed. This coefficient

indicates the probability,

beyond chance, that a second, independent

rater will assign

an item to the same category as the initial rater. Kappa was computed for each of the

eight dimensions.

In general, agreement among raters that trait items belonged in

the a priori dimensions was strong. Agreement was greatest for the Sensitivity factor

and lowest for the Strength factor. However, intra-category agreement was well beyond

chance for all eight factors. No significant differences between female and male raters

in intra-category

agreement were found. On this basis, 41 items comprising eight factors

were retained for hypothesis testing (see Figure 1). Table 2 presents the intercorrelations

of the eight revised factors in the sample from which they were derived. Whereas some

of the factors were found to be moderately intercorrelated,

the data from the sorting

task indicate that individuals can, and do, make clear conceptual distinctions among

these dimensions.

Tests of the Research Hypotheses

With the 41 items comprising

eight factors emerging from the sorting task, a

confirmatory

factor analysis was performed to test the hypothesis of different factor

structures across the two levels of rater sex and the three stimulus conditions for our

likelihood

parameter estimates of factor loadings.

Factor Structure of Implicit Leadership Theory Model Derived from Entire Sample

Numbers adjacent to manifest variable names represent maximum

Figure 1.

Note:

LEADERSHIP

52

QUARTERLY

Vol. 5 No. 1 1994

Table 2

Intercorrelations, Means, and Standard Deviations

of Implicit Leadership Theory Factors

Facfors

I. Sensitivity

2. Dedication

3. Tyranny

4. Charisma

5. attractiveness

6. Masculinity

7. Intelligence

8. Strength

(.93)

.47

-.38

.53

.I6

-23

.52

.I9

(.8U

c.911

.oQ

32

.48

-.07

.38

C%

.33

-.05

.58

.48

f.75)

.35

.31

.33

f.88)

-.04

.20

(.W

.42

(.6@

4.58

1.77

7.58

1.35

5.15

1.84

3.65

2.61

7.73

1.36

6.94

i.80

-.OI

.62

.21

-.07

.58

.3s

Mean

6.83

8.16

S.D.

1.69

1.22

Note: Numbersin parenthesesrepresent the

reliibilities

of each factor based on the reduced set of 41 items

Table 3

Summary of Models

Chfsqccare

Model

4f

MO: Null

2654.8

751

MI,:

3587.1

1502

-MIX: Separately by sex grouping, constrained

3661.0

1571

jMzB: Separately by stimulus type, unconstrained

4544.7

2253

iMZb: Separately by stimulus type, constrained

4706.2

2391

Separately by sex grouping, unconstrained

Note: Allps <

.OoOl.

original 686 subjects. Given that the original factor structure was derived from 160 items,

it was deemed prudent to test for possible differences in factor structures using the

reduced number of variables (Joreskog, 1971; Joreskog & Sorbom, 1979, 1980). The

formal statistical test for invariant factor structures compares the chi-square value

associated with an unconstrained model to the chi-square value associated with a

nested (i.e., more constrained) model in which corresponding factor loadings are

required to be identical across the groupings. Under the null hypothesis of invariant

factor structures across groups, this difference in chi-square values would, itself, be

expected to follow a chi-square distribution with an expected value equal to the

difference in the degrees of freedom of the constrained versus unconstrained models.

As Tables 3 and 4 show, significant differences in factor structure across groups were

not found, either across sex or across stimuIus groups. The comparatively high factor

loadings reflected in Figure 1 (which reflects the factor structure of the constrained

stimulus condition model) supports the tenability of the proposed model.

Given the invariance of factor structures across stimulus condition, a test of the

hypothesis of no level differences by stimulus condition and rater sex was conducted.

Implicit Leadership Theories

53

Table 4

Summary of Model Comparisons

Model Comparison

MO versus

MO versus

MI, versus

ML, versus

Now

Chi-square

df

932.3

1889.9

73.9

161.5

751

1502

69

138

<.Ol

<.Ol

.33

.08

MI,

M20

M,b

Mzb

See Table 3 for an explanation

of the models.

Table 5

Mean Factor Ratings of Leaders, Effective Leaders, and Supervisors

Stimulus Condition

Factor Name

Leaders

Effective Leaders

Sensitivity**

Dedication**

Tyranny*

Charisma**

Attractiveness

Masculinity

Intelligence**

Strength**

7.05

8.35

4.78

7.96

5.11

3.58

7.97

7.51

7.26

8.31

4.15

7.79

5.03

3.50

7.95

7.07

Nom:

Supervisors

6.22

7.8 1

4.69

6.99

5.25

3.79

7.27

6.28

p<.Ol.

** p < .ooOl

A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) performed on the eight factors revealed

significant main effects of stimulus condition, F(16,1262) = 9.84, p < .OOOl. Univariate

analyses revealed a significant stimulus condition effect on six factors: Sensitivity (F

= 22.50, p < .OOOl), Dedication (F= 18.59, p < .OOOl), Tyranny (F= 6.86, p < .Ol),

Charisma (F = 38.49, p < .OOOl), Intelligence (F = 17.45, p < .OOOl), and Strength

(F = 24.57, p < .OOOl). For four of these factors (Sensitivity, Dedication,

Charisma,

and Intelligence), leaders and effective leaders were viewed similarly, with both types

of leaders seen as possessing more of these characteristics than supervisors. Both leaders

and supervisors were considered more tyrannical than effective leaders. There was a

stepped pattern on the Strength factor, with leaders seen as stronger than effective

leaders, who were, in turn, viewed as stronger than supervisors.

Factor means by

stimulus condition are presented in Table 5.

Working Sample Validation

With our scale reduced

across target or perceiver

with working adults. Our

factors would generalize

more firsthand experience

to 41 items, and no evidence that the factor structure differed

sex, it was now feasible to validate the scale and its factors

particular concern was the extent to which the scale and its

to a noncollege sample of employed people who may have

with leaders, effective leaders, and supervisors.

54

LEADERSHIP

QUARTERLY

Vol. 5 No. 1 1994

Sample

Individual volunteers were solicited in public waiting areas of a large airport. Only

those indicating

full-time employment

were asked to participate.

There were 260

participants:

177 males and 83 females. Their mean age was 39.3 years, and they had

been employed full-time an average of 16.2 years. Individuals were employed in a range

of categories, notably professional (39%), managerial (300/o), sales (8%), and technical

(6%).

Procedure

The 41-item version of the scale was administered

to participants

individually.

Individuals were asked to rate how characteristic each of the traits were of a leader,

again with no explicit definition of the terms provided. Respondents

also were asked

to provide the demographic information

summarized above.

Results

A confirmatory factor analysis testing the hypothesis that each of the 41 items would

be significantly related to the same factor for working adults as was previously found

for undergraduates

was performed. No significant differences between samples were

found.

DISCUSSION

The present findings show eight primary dimensions

of peoples implicit theories of

leadership: Sensitivity, Dedication,

Tyranny, Charisma, Attractiveness,

Masculinity,

Intelligence, and Strength. Of these eight, those traits deemed most characteristic of

leaders, effective leaders, and supervisors (viz., Dedication, Charisma, Intelligence, and

Sensitivity) are all typically seen as positive attributes. Thus, these data support the

view that people generally view leaders, effective leaders, and supervisors in a positive

fashion and hold them up to high standards. However, our data also show that people

acknowledge

the possibility that individuals

in leadership positions may use their

positions to dominate,

control, and manipulate,

as well as inspire, motivate, and

support.

It was suggested that examining ILTs separately by nature of leader stimulus targets

and perceiver could yield information

about both factor stability across targets and

perceiver categories, and information

about differences in the level of ratings within

stimulus target. In terms of factor stability, the factor structure of implicit theories about

leaders did not differ across stimulus targets of leaders, effective leaders, and supervisors,

indicating that people use similar dimensions

for their perceptions

of these three

leadership targets. Likewise, ILT factors were similar for men and women perceivers,

and for student and worker groups. Since worker groups did not participate in item

generation,

it is possible that worker ILTs contain additional

unique elements

unrepresented

in our student-generated

item sample. This would not, however, alter

our findings of similar worker endorsement

of the student-generated

items, but rather

indicate that future research might be undertaken

to determine whether increased

exposure to target stimuli (as in a workers possibly greater exposure to multiple

organizational

superiors) significantly affects the richness of ILTs. The present research

Implicit Leadership Theories

55

indicates

that factors

used in considering

leader targets can show considerable

generalizability.

This generalizability

provides support for a view of ILTs as collectively

held expectations that are widely shared.

However, differences in level of rating between raters using these same factors were

found. As predicted, respondents perceived the three stimulus targets as possessing these

attributes to different extents. The largest difference was between supervisors and the

other two stimuli (leaders and effective leaders) with supervisors viewed as possessing

less of those characteristics typically considered most favorable, including Sensitivity,

Dedication, Charisma, Intelligence, and Strength. These results may contribute to the

ongoing debate among psychologists (e.g., Zaleznik, 1977) by suggesting that people

do not differ in the categories they use to think about leaders and supervisors but that

they do differentiate between supervisors and leaders in terms of prototypicality

ratings.

Expectations appear generally lower for supervisors than for leaders, with the exception

of the characteristic

represented by the Tyranny factor. Leaders and supervisors are

both seen as more likely to exhibit tyrannical tendencies than are effective leaders. These

data do not support an overall differentiation

in the perception of leaders versus effective

leaders, with leaders and effective leaders rated similarly on six of the eight factors.

It is possible that the cue of 1eadernaturally

calls forth the image of an effective leader.

Only when the leader cue includes a modifier presenting other information (e.g., political

leader) does the addition of the effectiveness cue appear to augment ratings (Foti et

al., 1982).

One goal of the present research was to determine how well explicit theories of

leadership reflect the salient issues raised in peoples ILTs, or whether some aspects

of leadership as evidenced by ILTs are neglected by existing explicit leadership theories.

Happily, a number of our factors are represented in present theory and research. Our

Sensitivity factor is similar to longstanding

concerns with leader consideration

(e.g.,

Fleishman,

1973). Charisma has a long history of study, and is currently enjoying a

resurgence of interest both within and apart from its key role in transformational

leadership (e.g., Bass, 1985). Physical characteristics summarized in our Attractiveness

factor were heavily researched by early theorists, with typically low positive relationships

found between leadership and attractiveness (see Bass, 1981, for a review). Intelligence,

although often found to be only weakly related to leader performance (e.g., Stogdill,

1974), or moderated by such variables as interpersonal

stress (e.g., Fiedler & Garcia,

1987) is nonetheless

strongly related to leader expectations

in the present study.

Research in the area of masculinity/femininity

and leadership continues to generate

interest, particularly

in regard to leader emergence. A recent study showed that

regardless of their sex, group members with masculine characteristics emerged as leaders

significantly

more than those with feminine,

androgynous,

or undifferentiated

characteristics,

and emergent

leaders received significantly

higher ratings

on

interpersonal

attractiveness (Goktepe & Schneier, 1989).

However, the key role of dedication, our most strongly endorsed factor, is not as

thoroughly researched. The importance of the hard work, diligence, preparation,

and

commitment

by leaders that is so strongly expected by others needs to be further

integrated into models of leadership. This is not the same as the well-researched areas

of task-orientation

(e.g., Fiedler, 1967) or initiating structure (e.g., Fleishman,

1973)

which reflect more of a concern with valuing task over people or getting the work done

56

LEADERSHIP

QUARTERLY

Vol. 5 No. 1 1994

through organizing or directing the work of others, respectively. For our participants,

dedication appears to be more centered within the leader, reflecting the leaders own

work ethic and motivation.

In this respect, our findings are consistent with Boyatzis

(1982) concept of efficiency orientation for effective leaders.

Strength and Tyranny also appear to be conceptually distinct and less well-integrated

into leadership theory. Tyranny, and perhaps Strength as well, may relate to feelings

of abuse of power, suggesting that a closer integration of models of power and leadership

is needed (Hollander & Offermann,

1990). Current work on the so-called dark side

of charismatic leadership (Hogan, Raskin, & Fazzini, 1990) may also be tapping the

same type of concerns we see in our Tyranny factor. Increased research attention is

needed to better understand this fearful view of leadership in the way it is commonly

understood by perceivers.

But perhaps the most important

research consideration

needs to be given to the

integration

of these different factors into a comprehensive

view of leadership rather

than as separate areas of study. Not only do we know less about some of these factors

than desirable, but we also have not considered them in conjunction

with all that we

do know about leadership. Lay perceivers may be the key to such integration, as these

various components of their implicit theories exist simultaneously.

These data support the utility of considering implicit theories of leadership for what

their content and structure can tell us, rather than treating such theories merely as

sources of rating error. The ultimate importance of ILTs may lie not only in how they

can bias our questionnaire

measures of leadership but also in the way in which they

ILTs are undoubtedly

reflected in the

structure the leader/follower

interaction.

expectations

that followers bring to the leader/follower

relationship.

Subsequent

research is needed to understand

how these expectations

affect the course of the

developing leader/follower

exchange. For example, one key area of future application

would be in the area of effective diversity management.

Different cultural groups may

have different conceptions of what leadership should be (Bass, 1990; Hofstede, 1993).

The English word leader does not even translate directly into languages such as

French, Spanish, or German, where available words such as le meneur, el jefe, or de

Fuhrer tend to connote only leadership that is directive (Graumann,

1986). The ILTs

of individuals from such backgrounds might differ dramatically from the United Statesfollowers

who expect

leader

based findings

presented

here. For example,

authoritarianism

may view leader sensitivity as a sign of weak leadership and evaluate

such behavior negatively. Understanding

ILTs might be useful in linking different

follower expectations with responses to leader behavior.

The present research has shown that differences in implicit theories across leadership

targets and across raters can be systematically examined. Using a different methodology

from previous research, the results are nonetheless consistent with Lords leadership

categorization

theory, and further serve to highlight areas where leadership theory,

research, and practice needs to integrate important areas of leader perceptions.

Acknowledgments:

Thanks are due to Elaine Belansky and Audrey Goldman for

collecting the working sample data, to Don Gallo for conducting the content validation,

and to Larry James, Bob Lord, and George Rebok for comments on an earlier draft

of the manuscript.

57

Implicit Leadership Theories

NOTE

1. Similar results might be expected with the use of the word manager, when that term

clearly connotes the immediate superior. Because the term manager may be used by individuals

to identify superiors at several different hierarchical levels above them, whereas supervisor more

clearly refers to the immediate superior, we chose to use the term supervisor in this study to

provide greater clarity about the target.

REFERENCES

Ayman, R. (1993). Leadership perception: The role of gender and culture. In M.M. Chemers

& R. Ayman (Eds.), Leadership theory and research: Perspectives and directions. New

York: Academic.

Bass, B.M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. New York: Free Press.

Bass, B.M. (1981). Stogdillk handbook of leadership. New York: Free Press.

Bieri, J., Atkins, A.L., Briar, S., Leaman, R.H., Miller, H., & Tripodi, T. (1966). Clinical and

social judgement. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Borman, W.C. (1987). Personal constructs,

performance

schemata, and folk theories of

subordinate effectiveness: Explorations in an army officer sample. Organizational Behavior

and Human Decision Processes, 40. 307-322.

Boyatzis, R.E. (1982). The competent manager. New York: John Wiley.

Eden, D., & Leviatan, U. (1975). Implicit leadership theories as a determinant

of the factor

structure underlying supervisory behavior scales. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60, 736741.

Fiedler, F.E. (1967). A theory of leadership effectiveness. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Fiedler, F.E., & Garcia, J.E. (1987). New approaches to leadership: Cognitive resources and

organizational performance. New York: Wiley.

Fleishman, E.A. (1973). Twenty years of consideration and initiating structure. In E.A. Fleishman

and J.G. Hunt (Eds.), Current developments in the study of leadership (pp. l-37).

Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Fleiss, J.L. (1971). Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychological

Bulletin, 76, 378-382.

Foti, R.J., Fraser, S.L., & Lord, R.G. (1982). Effects of leadership labels and prototypes on

perceptions of political leaders. Journal of Applied Psychology, 67, 326-333.

Goldstein, K.M., & Blackman, S. (1978). Cognitive style. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Gioia, D.A., & Sims, H.P., Jr. (1985). On avoiding the influence of implicit leadership theories

in leader behavior descriptions. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 45.217-232.

Goktepe, J.R., & Schneier, C.E. (1989). Role of sex, gender roles, and attraction in predicting

emergent leaders. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 165-167.

Graumann, C.F. (1986). Changing conceptions of leadership: An introduction. In C.F. Graumann

& F. Moscovici (Eds.), Changing conceptions of leadership. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Hinkin, T.R., & Schriesheim, C.A. (1986, August). Influence tactics used by subordinates:

A

theoretical and empirical analysis and refinement of the Kipnis, Schmidt, and Wilkinson

subscales. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Academy of Management,

Chicago, Illinois.

Hofstede, G. (1993). Cultural constraints in management theories. 7he Executive, 7, 81-94.

Hogan, R., Raskin, R., & Fazzini, D. (1990). The dark side of charisma. In K.E. Clark & M.B.

Clark (Eds.), Measures of leadership (pp. 343-354). West Orange, NJ: Leadership Library

of America.

LEADERSHIP QUARTERLY

58

Vol. 5 No. 1 1994

Hollander, E.P., & Offermann, L.R. (1990). Power and leadership in organizations: Realtionships

in transition. American Psychologist, 4.5, 179-189.

Joreskog, K.G. (1971). Simultaneous factor analysis in several populations. Psychometrika,

36,

409-426.

K.G., & Sorbom, D. (1979). Advances in factor analysis and structural equation

Cambridge, MA: Abt Associates.

Joreskog, K.G., & Sorbom, D. (1980). LZSREL-IV users guide. Chicago: National Educational

Resources.

Klatzky, R.L. (1980). Human memory: Structure andprocesses.

San Francisco: Freeman.

Koltuv, B.B. (1962). Some characteristics

of intrajudge train intercorrelations.

Psychological

Monographs,

76(33, whole no. 552).

Lord, R.G., Foti, R.J., & DeVader, CL. (1984). A test of leadership categorization

theory:

Internal structure, information

processing, and leadership perceptions.

Organizational

Joreskog,

models.

Behavior

and Human

Performance,

34, 343-378.

Lord, R.G., Foti, R.J., & Phillips, J.S. (1982). A theory of leadership categorization.

In J.G.

Hunt, U. Sekaran, & C.A. Schriesheim (Eds.), Leadership: Beyond establishment views.

Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Mervis, C.B., Catlin, J., & Rosch, E. (1976). Relationships among goodness-of-example,

category

norms, and word frequency. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 7, 283-284.

Mervis, C.B., & Rosch, E. (1981). Categorization

of natural objects. Annual Review of

Psychology,

32, 89-

115.

Phillips, J.S., & Lord, R.G. (1982). Notes on the practical and theoretical consequences of implicit

leadership theories for the future of leadership measurement. Journal of Management,

12,

31-41.

Rosch, E. (1978). Principles of categorization.

In E. Rosch & B.B. Lloyd (Eds.), Cognition and

categorization.

Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Rush, M.C., Thomas, J.C., Kc Lord, R.G. (1977). Implicit leadership theory: A potential threat

to the validity of leader behavior questionnaires.

Organizational Behavior and Human

Performance,

20, 93-l 10.

Schneider, D.J. (1973). Implicit personality theory: A review. Psychological Bulletin, 79, 294309.

Sternberg,

R.J. (1985). Implicit

Personality

theories

and Social Psychology,

of intelligence,

creativity,

and wisdom.

Journal

of

49, 607-627.

Sternberg, R.J. (1988). The triarchic mind: A new theory of human intelligence. New York:

Viking.

Tinsley, H.E.A., & Weiss, D.J. (1975). Interrater

reliability and agreement of subjective

judgments. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 22, 358-376.

Zaleznik, A. (1977). Managers and leaders: Are they different? Harvard Business Review, 5.5,

67-78.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Infosys Class NotesDocumento1 paginaInfosys Class NotesGloryNessuna valutazione finora

- Business ConsiderationsDocumento1 paginaBusiness ConsiderationsGloryNessuna valutazione finora

- Stakeholder Engagement PlanDocumento1 paginaStakeholder Engagement PlanGloryNessuna valutazione finora

- The Entrepreneur's Roadmap: A Guide to Business Launch, Growth and Global AmbitionDocumento5 pagineThe Entrepreneur's Roadmap: A Guide to Business Launch, Growth and Global AmbitionGloryNessuna valutazione finora

- Learning Points - Business LawDocumento1 paginaLearning Points - Business LawGloryNessuna valutazione finora

- Corporate PersonalityDocumento1 paginaCorporate PersonalityGloryNessuna valutazione finora

- Change Management D V F R I Do Too Much Communication (One-Way) and Little EngagementDocumento1 paginaChange Management D V F R I Do Too Much Communication (One-Way) and Little EngagementGloryNessuna valutazione finora

- Online Video Rentals in Lekki to Decline 18Documento1 paginaOnline Video Rentals in Lekki to Decline 18GloryNessuna valutazione finora

- O Leadership o People ManagementDocumento1 paginaO Leadership o People ManagementGloryNessuna valutazione finora

- Career ManagementDocumento1 paginaCareer ManagementGloryNessuna valutazione finora

- Mis Learning PointsDocumento1 paginaMis Learning PointsGloryNessuna valutazione finora

- SafeguardsDocumento1 paginaSafeguardsGloryNessuna valutazione finora

- Digital Transformation of First Bank 1Documento2 pagineDigital Transformation of First Bank 1GloryNessuna valutazione finora

- Managing Your CareerDocumento1 paginaManaging Your CareerGloryNessuna valutazione finora

- Leading People Through ChangeDocumento1 paginaLeading People Through ChangeGloryNessuna valutazione finora

- Leadership Challenges in The 21st CenturyDocumento1 paginaLeadership Challenges in The 21st CenturyGloryNessuna valutazione finora

- EMBA 21 - Assessing a Company's New Product ProcessDocumento1 paginaEMBA 21 - Assessing a Company's New Product ProcessGloryNessuna valutazione finora

- E CommerceDocumento1 paginaE CommerceGloryNessuna valutazione finora

- Paul in Magna LimitedDocumento1 paginaPaul in Magna LimitedGlory100% (1)

- Mrs Maiya and Clinton Health AccessDocumento1 paginaMrs Maiya and Clinton Health AccessGloryNessuna valutazione finora

- Creating Dynamic Competitive AdvantageDocumento1 paginaCreating Dynamic Competitive AdvantageGloryNessuna valutazione finora

- The Concept of StrategyDocumento3 pagineThe Concept of StrategyGloryNessuna valutazione finora

- Strategy Learning PointsDocumento1 paginaStrategy Learning PointsGloryNessuna valutazione finora

- Responsibility of Regulatory Authorities Responsibility of Collaborators With EddieDocumento1 paginaResponsibility of Regulatory Authorities Responsibility of Collaborators With EddieGloryNessuna valutazione finora

- Earnings Management at CadburyDocumento1 paginaEarnings Management at CadburyGloryNessuna valutazione finora

- Wal-Mart's Competitive AdvantageDocumento1 paginaWal-Mart's Competitive AdvantageGloryNessuna valutazione finora

- Leading People Through ChangeDocumento1 paginaLeading People Through ChangeGloryNessuna valutazione finora

- Digital Business TransformationDocumento1 paginaDigital Business TransformationGloryNessuna valutazione finora

- Steel Screen - B2B ExchangesDocumento92 pagineSteel Screen - B2B ExchangesGloryNessuna valutazione finora

- SteelscreenDocumento1 paginaSteelscreenGloryNessuna valutazione finora

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Appointment Letter JobDocumento30 pagineAppointment Letter JobsalmanNessuna valutazione finora

- IS BIOCLIMATIC ARCHITECTURE A NEW STYLE OF DESIGNDocumento5 pagineIS BIOCLIMATIC ARCHITECTURE A NEW STYLE OF DESIGNJorge DávilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Manzano's and Kendall Taxonomy of Cognitive ProcessesDocumento5 pagineManzano's and Kendall Taxonomy of Cognitive ProcessesSheena BarulanNessuna valutazione finora

- McKinsey & Co - Nonprofit Board Self-Assessment Tool Short FormDocumento6 pagineMcKinsey & Co - Nonprofit Board Self-Assessment Tool Short Formmoctapka088100% (1)

- Navid DDLDocumento7 pagineNavid DDLVaibhav KarambeNessuna valutazione finora

- Fazlur Khan - Father of Tubular Design for Tall BuildingsDocumento19 pagineFazlur Khan - Father of Tubular Design for Tall BuildingsyisauNessuna valutazione finora

- Tiger Facts: Physical Characteristics of the Largest CatDocumento14 pagineTiger Facts: Physical Characteristics of the Largest CatNagina ChawlaNessuna valutazione finora

- HTTP - WWW - Aphref.aph - Gov.au - House - Committee - Pjcis - nsl2012 - Additional - Discussion Paper PDFDocumento61 pagineHTTP - WWW - Aphref.aph - Gov.au - House - Committee - Pjcis - nsl2012 - Additional - Discussion Paper PDFZainul Fikri ZulfikarNessuna valutazione finora

- Activity Emcee Mid-Year INSET 2021Documento3 pagineActivity Emcee Mid-Year INSET 2021Abegail A. Alangue-Calimag67% (6)

- Tutor Marked Assignment (TMA) SR Secondary 2018 19Documento98 pagineTutor Marked Assignment (TMA) SR Secondary 2018 19kanna2750% (1)

- NX569J User ManualDocumento61 pagineNX569J User ManualHenry Orozco EscobarNessuna valutazione finora

- Subject and Power - FoucaultDocumento10 pagineSubject and Power - FoucaultEduardo EspíndolaNessuna valutazione finora

- ArrayList QuestionsDocumento3 pagineArrayList QuestionsHUCHU PUCHUNessuna valutazione finora

- Capitalism Communism Socialism DebateDocumento28 pagineCapitalism Communism Socialism DebateMr. Graham Long100% (1)

- Embedded Systems - RTOSDocumento23 pagineEmbedded Systems - RTOSCheril MehtaNessuna valutazione finora

- QQQ - Pureyr2 - Chapter 3 - Sequences & Series (V2) : Total Marks: 42Documento4 pagineQQQ - Pureyr2 - Chapter 3 - Sequences & Series (V2) : Total Marks: 42Medical ReviewNessuna valutazione finora

- Decision MatrixDocumento12 pagineDecision Matrixrdos14Nessuna valutazione finora

- Servo Magazine 01 2005Documento84 pagineServo Magazine 01 2005dangtq8467% (3)

- RealPOS 70Documento182 pagineRealPOS 70TextbookNessuna valutazione finora

- Light Body ActivationsDocumento2 pagineLight Body ActivationsNaresh Muttavarapu100% (4)

- Literary Text Analysis WorksheetDocumento1 paginaLiterary Text Analysis Worksheetapi-403444340Nessuna valutazione finora

- Rolfsen Knot Table Guide Crossings 1-10Documento4 pagineRolfsen Knot Table Guide Crossings 1-10Pangloss LeibnizNessuna valutazione finora

- Remapping The Small Things PDFDocumento101 pagineRemapping The Small Things PDFAme RaNessuna valutazione finora

- Structural Testing Facilities at University of AlbertaDocumento10 pagineStructural Testing Facilities at University of AlbertaCarlos AcnNessuna valutazione finora

- Design Theory: Boo Virk Simon Andrews Boo - Virk@babraham - Ac.uk Simon - Andrews@babraham - Ac.ukDocumento33 pagineDesign Theory: Boo Virk Simon Andrews Boo - Virk@babraham - Ac.uk Simon - Andrews@babraham - Ac.ukuzma munirNessuna valutazione finora

- Signal Processing Problems Chapter 12Documento20 pagineSignal Processing Problems Chapter 12CNessuna valutazione finora

- NMIMS MBA Midterm Decision Analysis and Modeling ExamDocumento2 pagineNMIMS MBA Midterm Decision Analysis and Modeling ExamSachi SurbhiNessuna valutazione finora

- Studies On Diffusion Approach of MN Ions Onto Granular Activated CarbonDocumento7 pagineStudies On Diffusion Approach of MN Ions Onto Granular Activated CarbonInternational Journal of Application or Innovation in Engineering & ManagementNessuna valutazione finora

- NAVMC 3500.35A (Food Services)Documento88 pagineNAVMC 3500.35A (Food Services)Alexander HawkNessuna valutazione finora

- The Basics of Hacking and Pen TestingDocumento30 pagineThe Basics of Hacking and Pen TestingAnonNessuna valutazione finora