Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Human Motivation in The Work Organization:: I. Productivity, Job Satisfaction, and Motivation

Caricato da

ShreekumarTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Human Motivation in The Work Organization:: I. Productivity, Job Satisfaction, and Motivation

Caricato da

ShreekumarCopyright:

Formati disponibili

HUMAN MOTIVATION IN THE WORK ORGANIZATION:

THEORIES AND IMPLICATIONS

Lamp Li

productivity. Generally, we judge managers by two

I. Productivity, Job Satisfaction, and Motivation

important

In a modern society, one of the central pro-

considerations

of

production

and

people, which in turn are based on the three factors

blems is to provide jobs for all those who want and

of

are able to work. But once people get jobs, it is

interpersonal

for the management of any organization, business

driven mainly by the need for self-actualization,

motivation, participative management, and

competence. Good managers are

or governmental, to worry about employee motiva-

and are deeply interested in both people and pro-

tion: because employee motivation or motivation of

duction. They are both high-task and high-relation-

organizational members is one of the critical func-

ship oriented. Average managers are concerned with

tions of a manager, and because there is a persist-

ego status, and are high-task, low-relationship

ently increasing pressure for increased productivity

oriented. Poor managers are preoccupied by safety

in order to meet competition, to best utilize scarce

resources, and to provide goods and services to

and ego-status needs, they are of low-task, lowrelationship kind of people. Their guides are

more and more people at less and less cost.

personnel manual and SOPs, and their goal is simply

In fact, employee motivation has been very

self-preservation.

popular in management circles. Motivation, in its

traditional

sense

among

management

writers,

Motivation is often mistakenly teamed with

job

satisfaction,1

resulting

in misconceptions

means a process of stimulating people to action to

about the relationships between productivity, job

accomplish desired goals. It is a crucial factor in

satisfaction and motivation.

judging management style as well as in determining

-253-

Traditional views treat employee satisfaction

NEW ASIA COLLEGE ACADEMIC ANNUAL VOL. XIX

as an input that contributes to productivity. How-

Thus, employee satisfaction does not neces-

ever, researches by industrial relations people

sarily lead to high employee performance, while

since early 1950s suggest that it is rather an output

highly productive employees are not necessarily

in the short run, although in the long run a

the

minimum level of satisfaction is considered neces-

management can provide both productivity and

sary and should be maintained. This change in

satisfaction. In fact, productivity and satisfaction

thinking is best seen in the following theoretical

are determined by different sets of factors. This

model on productivity-satisfaction relationships as

may be seen from the following brief listing:

highly

satisfied employees.

But

effective

developed by Porter and Lawler. (See Figure 1 .)

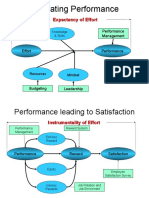

Figure 1. The Performance-Reward-Satisfaction Model

Perceived equitable

rewards

Employee's perceptions

of both his worth and

rewards

Intrinsic rewards

(Rewards an employee gives

himself for doing a good job)

People like to do a good job;

The employee himself gives

and controls the reward;

so

Very closely related to

performance;

Extrinsic rewards

(Pay, promotion, employee

benefits, . . .)

Organizationally controlled;

Given through performance

appraisalwhich at best

is an art, so

Not so closely related to

performance as intrinsic

rewards

Adapted from: Edward E. Lawler, III and Lyman W. Porter,

Managerial Attitudes and Performance, Irwin,

1968, p. 165.

-254

HUMAN MOTIVATION IN THE WORK ORGANIZATION

Figure 2. Determinants of Productivity and Job Satisfaction

Determinants of productivity

Determinants of job satisfaction

Resource utilized

Technology (plant, equipment, process, . . . . )

Raw materials

Job or work situation:

Pay and promotion

Degree of job specialization

Job level

Supervision

Recognition of ability

Fair evaluation of work

Work groups

Employee's job performance

Ability to perform:

Skills

Knowledge

Motivation to perform

Physical conditions

job layout, safety, lighting, ventilation, rest

periods, music,...

Social conditions

status and role, group dynamics, influence

systems, leadership,...

Individual's needs

physiological, social, egoistic, . . .

Personal characteristics:

Age

Sex

Education

Personality

Health

Social, cultural and situational environments:

Family relationship

Social status

Recreational outlets

Activities in the Organization (labor, political,

purely social, etc.)

Economic characteristics of the community

(poor or wealthy)

In general, productivity depends on 3 things:

resources utilized, employee's ability to perform,

and employee's willingness to work or motivation to

perform. Although motivation is not the sole

determinant of productivity, it is a determinant of

crucial importance. Without motivation, resources

and ability will be of little avail, or may even result

in undesirable behavior.

II. Motives Behind Human Behavior

-255-

A theory on motivation-to-work must at

least answer the following questions:

Why do people work in the first place? (the

decision to work)

Why do people choose a particular occupation?

(the occupation choice)

Why do individuals join a particular organization? (the decision to join an organization)

Why do some individuals decide to use their

abilities to the maximum? (the decision

NEW ASIA COLLEGE ACADEMIC ANNUAL VOL. XIX

siological needs), sex (restaurant provides a meeting

to use abilities to the maximum)

Why do some people leave an organization in

place for extra-marital affair), status (you want to

search of other position? (the decision to

be seen in a prestigious restaurant), or else. Further-

leave an organization)

more, motivation is but one of the three psycho-

Each decision or

choice has its own set of

logical processes or causes that explain the human

behavior.

What we are interested in is employee motivation on

learning.

determinants which we will not elaborate here.

the job and in an organizational context.

The other two being perception and

The basic drives or motives behind human

Motivation is a general

behavior are needs.6 There are many kinds or

term applying to the entire class of drives, desires,

categories of needs. The first writer who related

What is motivation?

needs, and wishes. It is essentially a process by

human needs within a need-hierarchy framework is

which an individual attempts to satisfy certain

Abraham Maslow7 But this hierarchy refers to the

needs by engaging in various behaviors. A motivated

motivational scale of normal, healthy people living

behavior is goal-directed, sustained, and is a result

in a relatively highly developed society. Moreover,

from internal needs and drives. Not all behavior is

Maslow did not apply his need hierarchy directly

motivated, but most of work behavior is motivated.

to work motivation until about 20 years later.8

A motive is an internal drive that "arouses, directs,

In the meantime, his propositions have been subject

and integrates a person's behavior." Psychologists

to many criticisms and modifications.9 Despite this,

like to classify motives or drives into Primary,

his need hierarchy concept has been widely used as

General,

and Secondary

categories.

However,

a theoretical foundation for management approach

motives may be quite complex and often conflict-

to motivation, especially managerial motivation.

ing. They cannot be seen or observed directly, they

can only be inferred from the behavior, or simply

III. Theories of Motivation

assumed to exist in order to explain the behavior.

Based on the concept of needs, and employ-

But alas, motives cannot always be inferred from

the behavior.5 For example, you eat at a restau-

ing the valence-expectancy

rant, what is your motive? It may be hunger (phy-

process may be presented as follows:

formulation,

and

instrumentality

a basic model of the motivation

Figure 3. A Basic Model of the Motivation Process

Need

(motive,

tension)

<>

Valence (the strength of an individual's preference for a particular

outcome)

1

Perception and selection of outcomes

which have potential for need satis-

faction

t

Expectancy (probability that a particular action will lead to a particular

outcome)

Action r*

Motivation

-256 -

First level

outcomes

(rewards):

Pay

Recognition

Promotion

Internal

satisfaction

Instrumentality

Second level

outcomes

(need satisfaction):

Power

Security

Esteem

Social

HUMAN MOTIVATION IN THE WORK ORGANIZATION

From this basic process which is more or less

generally accepted to-day, it should be obvious

that the important driving force is the degree to

which the individual values certain rewards or

second-level outcomes or, what needs are

operating at what strength to motivate the individual's behavior. Against the background of the

relatively highly developed Western societies,

modern behaviorists would say that the lower-level

(physiological and safety) needs are generally

satisfied in modern industry. What is neglected

or less explored is the higher-level needs, so they

put much more emphasis on higher-level need

satisfaction in the work organization.

But their approaches to or concepts about

motivators are different. Such differences are only

natural when we consider the fact that in the-study

of employee motivation, the role of money (compensation systems), leadership, technology, job

content, work environment, etc. have all to be

considered.10 Management literature abounds with

different formulations of theories and empirical

studies about motivation. While full descriptions of

them are readily available elsewhere, it may be

worth while to briefly note here some of the

differences, bearing in mind the important point of

agreement that individual employees attempt to

satisfy many needs through their work and through

their relationship with an organization.

Somewhat along the traditional line of viewing motivation as something imposed on an

employee, Douglas McGregor and Rensis Likert

put much emphasis on management style. They

opined11 that leadership (manager) behavior based

on Theory Y assumption or system 4 management

would lead to management practice that provides

-257-

democratic leadership and employee participation,

making employees feel real responsibility for organization's goals. This management (leadership) style

is asserted to produce better results in productivity

and job satisfaction, as it motivates the subordinates

to achieve job objectives. Several points need be

made clear here. First, Theory Y is not permissive!

In fact, it is even sterner than Theory X because

it has to achieve what Theory X achieved, and then

do a good deal more. Secondly, while leadership

style and management practice influences employee

motivation, the latter also influences the former.

Thirdly, Likert's motivational forces include both

economic rewards and the higher-level needs.

Indeed, his approach embraces the entire need

hierarchy and considers the whole man. And he

cautioned that application of the basic principles

of system 4 management should take into account

the differences in the kind of work, industry tradition, and skills and values of employees of a particular company.

Similar in nature to, but broader in scope

than, the above line of thinking is the call for an

organization structure and work environment that

would provide opportunity for internal and external

integration, employee participation, self-expression,

and self-actualization. Authors like Bakke, Argyris,

Bennis, Litwin and Stringer12 opined that the

traditional structure of rigid specialization, welldesigned jobs, and standard operating procedures

(so-called bureaucratic-mechanistic structure) can

hardly provide such work environment whose

basic ingredients consist of nature of task (involving technology and social and psychological processes), work group, and leadership. Only an

adaptive-organic system can provide a high degree

NEW ASIA COLLEGE ACADEMIC ANNUAL VOL. XIX

of job flexibility, initiative, variety, and enrichment

nally

to match the varied interests and multiple talents

behavior on the job, but not "motivate" behavior.

of modern man.

13

installed

generators,

they

"determine"

This adaptive-organic structure

Without proper provisions for them, they will cause

and environment is especially suitable for organi-

job dissatisfaction or negative motivation. However,

zations using dynamic technologies.

even with adequate provisions, they can only

On the other hand, there are behaviorists

prevent dissatisfaction, but cannot lead to positive

who seek to search for the inner forces which

and persistent motivation. So they are "dissatis-

energize and move the individual into goal-directed

fiers" by nature. The motivators, on the other

behavior. Among them, Frederick Herzberg is

hand, are the inner generators and are strongly

perhaps the most widely known author.

motivating. Since they are strongly motivating,

Herzberg differentiated two sets of needs:

they can't also be demotivating when they are not

Animal need and uniquely human need. He applied

provided. So they are "satisfiers" by nature. 14

these sets of need to work situations and made a

Herzberg's framework may be shown in the follow-

clear-cut

ing figure:

distinction

between

motivators

and

hygiene factors. The hygiene factors are the exterFigure 4: Herzberg's Two-Factot Theory of Motivation

Uniquely human need

Animal need

corresponds to

corresponds to

Maslow's lower-level needs

Maslow's higher-level needs

taken care by

taken care by

Hygiene or maintenance factors

(Dissatisfiers):

Company policy & adm.

Quality of supervision

Interpersonal relationship

Working conditions

Salary & fringe benefits

Status

Security

Real motivators

(Satisfiers):

Achievement

Recognition of achievement

Intrinsic interest of the work

Job responsibility

Growth or advancement

Related to

Related to

Job content: directly related to the job

itself

Job context or job environment: peripheral

to the job

Herzberg's theory has been subject to heavy

criticism by academicians, and evidence against his

- 258 -

HUMAN MOTIVATION IN THE WORK ORGANIZATION

theory

for

seems

to

evidence

become a widely known theory that describes the

it. For one thing, his theory is strictly

motivation process (refer to Figure 3), and has been

uni-dimensional:

be

factor

than

either be

supported by most of the studies that have tested

a satisfier or a dissatisfier, but cannot be both.

it. The theory takes into account individual differ-

But

there are

ences in the prediction of motivated behavior, but

job factors which lead to both satisfaction and

it offers little help for actually motivating employ-

dissatisfaction. Money and inter-personal relation-

ees.

many

a job

greater

can

research findings show

ship are good examples. Even fear of punishment

continues to be a strong motivator. Also, his theory

IV. Practical Implications

assumes that the motivator and hygiene factors

From the foregoing, we may say that needs

operate in the same fashion for everyone. This is

are the origin of much of human motivation. Motiv-

just not true. Furthermore, his theory is somewhat

ators are the inner generators of an employee. The

method-bound (he used the critical incident tech-

generators have to be incited or ignited by an

nique which generate results supporting his theory).

appropriate organizational climate.17 The logic of

Despite these criticisms, his theory has made some

all this sounds rather simple, but the implications

major contributions toward our understanding of

for action are quite complex and delicate. In what

motivation by applying need hierarchy concept to

follows, the author will attempt to raise some

the work setting. Indeed, he is the one who is

questions in regard to the translation of conceptual

truly concerned with the role of job content in

knowledge into practice.18

employee

of job

First, exactly what are the motivators? There

principles may be over-simplifying

is no definite answer despite Herzberg's assertion

matters, but they do provide practical ways for

to the contrary. It would depend on different

enrichment

motivation.

His applications

motivating employees, and have greatly influenced

societies, different individuals, and different organi-

managerial practices in the modern business world.

zational or job levels. There is probably no universal

Victor Vroom, after criticizing Herzberg's

motivator for all mankind, nor is there a single

theory as merely a theory of job satisfaction, deve-

motivating force for any one individual. It is a

loped an alternative valence-expectancy theory of

problem of what mixture of needs for what kind of

motivation. According to Vroom, the strength (or

people in what kind of society. In Hong Kong, for

force) of the motivation to act or to behave is a

example, there is no doubt that money is a predo-

function of the algebraic sum of the products of

minant motivator with regard to both the lower-

valences multiplied by expectancies or probabilities

level need satisfaction and the fulfillment of status

(i.e., SViPi). The valence refers to one's feelings;

and achievement goals.

it may be zero, negative, or positive, depending on

Secondly, in motivating employees, managers

the individual,15 In recent years, there have been

have to identify the operative needs and job-related

many

goals of the employees. Or, they have to devise

elaborations

Vroom's theory.

16

or

reconceptualizations of

Generally

speaking, it has

-259-

some goal-setting process with employees' partici-

NEW ASIA COLLEGE ACADEMIC ANNUAL VOL. XIX

pation. This is already a formidable job. Moreover,

after the operative needs and job-related goals are

identified in a particular situation, there is the

problem of availability of rewards to satisfy the

needs through goal fulfillment. In other words,

does each and every employee perceive the rewards

as available, not just what management says is

available? Many rewards necessary to insure

employee motivation and goal-fulfillment just do

not exist in many organizations. In such organizations, rewards are provided for, or focused on, lower

level needs, so that the higher level needs never

become active.

A closely related problem is how consistent

is the linkage between high performance and the

attainment of desired rewards. If the linkage is

inconsistent and the employee sees a low probability of achieving a desired reward, a motivation

problem will arise and performance-related

behavior will be reduced, even though the reward is

clearly shown as available by the management.

Thirdly, achievement is generally recognized

as an important motivator for higher level performance. But in many organizations, there are no welldefined, achievable task objectives set by management or mutually agreed upon between management and employees, nor is there clear identification of group task objectives and their linkage to

task-responsibilities of individuals in the group.

Under such circumstances, the employee would

lose his direction and his achievement motivation

would be deprived of its very pre-requisite. Moreover, employee's performance must be evaluated

against the set task objectives, and there must have

open, accurate, specific (not generalized) feedback

available to the employee as to how he is doing.

-260-

Many managers and company managements have

failed in the implementation of employee motivation, because they failed to recognize the importance of goal or objective setting and performance

feedback as motivational tools.

Lastly, something need be said about the

motivational possibilities intrinsic to the work

itself. This is the job enrichment theme, so much

stressed by Herzberg and associates and also so

popular and controversial. 19 Job enrichment is to

enrich the job content by providing more varied and

challenging content in the work so as to change

employee's behavior directly. Its essential elements

are: (1) Design the work module to give the

employee or work group a natural unit of work and

responsibility, (2) Considerable or complete control

of the work module by the employee or work

group, (3) Sufficient direct feedback of work

results to the employee or work group, and (4)

Appropriate standards for measuring performance.

While job enrichment programs have been widely

applied in many countries and industries, management writers and practitioners still question their

real effectiveness.

Conceptually, job enrichment, by itself alone,

provides only a partial answer to the innovative

efforts to re-design the total work organization, and

has typically failed in its limited objective because

the organizational system often returns to its earlier

equilibrium.20 Moreover, individuals differ vastly.

Many employees prefer low-level competency,

security, and relative independence to responsibility, growth, and team participation. To them, job

content is' not automatically related to job satisfaction, and motivation not necessarily a function

of job satisfaction. They often find higher-level

HUMAN MOTIVATION IN THE WORK ORGANIZATION

need satisfaction outside the work environment.

Also, there is the difficulty of continuously

supplying "challenges."

Practically, there are many questions about

implementation. Managers often do not know what

is necessary to implement a job enrichment program, or don't like (resist) to change their role or

thinking. Since many meaningful tasks must be

added and boredsome ones removed, good, intellectualized learning (e.g., training programs and

classes) cannot be the substitute for practice and

experience. Do managers carefully study what kind

of work can be enriched? Are key, responsible

individuals assigned to attack the many tough

issues involved beforehand? Have the employees

participated in the work re-design project so that it

is not imposed on them? Has the work itself not

actually changed after the redesign due to resist-

-261

ance, confusion, or bureaucratic practice? Does the

top management gives support and commitment

such as budget overruns, rewards for extra efforts,

. . . ? Is there systematic and continuous evaluation

of the work re-design project once it is undertaken?

Such questions are very crucial to the success of

any job enrichment program, even if we concede

conceptually that job enrichment is the most

effective motivating technique.

The author has briefly reviewed several motivation theories and discussed some of the practical

implications for managerial action. It seems that the

difficulty lies not so much in theorizing as in

actual implementation. Thus what is the appropriate approach and action program toward

employee motivation in a particular organization

remains therefore the toughest job for its

managers to accomplish.

NEW ASIA COLLEGE ACADEMIC ANNUAL VOL. XIX

'Job satisfaction refers to the feeling(s) which an employee has about his total job situation, including other job alternatives available besides his present job.

2

See Dunn and Stephens, Management of Personnel, Manpower Management and Organizational Behavior, McGraw-Hill,

1972, pp. 164-174.

3

Some psychologists classify three main categories of behavior:

Motivated behavior characterized by persistent goal orientation;

Frustration-instigated behavior or behavior without a goal;

Reflexes and automatic behavior determined only by neural connections.

"Primary - unlearned and physiologically based, such as hunger, thirst, sleep, sex.

General also unlearned, but not physiologically based, such as motives for competence, curiousity, manipulation,

activity, affection.

Secondary - learned and most relevant to organizational behavior, such as power, achievement, affiliation, security,

status.

5

Ernest R. Hilgard & Richard C. Atkinson in their Introduction to Psychology (4th ed., Harcourt, Brace & World, 1967,

pp. 141-142) summarized 5 reasons for this difficulty:

The expression of human motives differ from culture to culture and from person to person within a culture.

Similar motives may be manifested through unlike behavior.

Unlike motives may be expressed through similar behavior.

, Motives may appear in disguised forms.

Any single act of behavior may express several motives.

6

But recent studies by biological scientists indicated that needs are not always the cause of human behavior, but a result

of it. They say behavior is often what we do, not why we do it.

'Abraham Maslow, "A Theory of Human Motivation," Psychological Review, July 1943, pp.370-396; also,Motivation

and Personality, Harper & Row, 1954.

8

See Maslow, Eupsychian Management, Irwin & the Dorsey Press, 1965. In a very rough manner, Maslow's need

hierarchy theory can be converted into a content model of work motivation, as follows:

Needs:

Contents:

Self Actualization \

Ego needs

Social needs

Achievement feeling

\

Titles, status symbols, promotions, banquets

\

Safety needs

Basic or physiological needs

Formal & informal work groups

\

Seniority plans, union, severance pay

\

Pay

Maslow estimated that 85% of basic needs, 70% of security needs, 50% of belonging needs, 40% of esteem needs, and 10% of

self-actualization needs are satisfied in organizations generally (in western societies).

'The following indicate some of the criticisms and modifications:

The specific 5-category system and its internal ordering have little empirical validity, not every one follows exactly

that pattern;

The theory tells us very little about how to activate motivation;

Some management writers classify needs into "higher needs" and "lower needs" (M.A. Wahba and L.G. Bridwell),

or "achievement need" (n Ach), "power need" (n Pow), and "affiliation need" (n Aff) (D.C. McClelland and associates); or "existence," "relatedness," and "growth" (C.P. Aldefer); or "animal need" and "uniquely human need"

(F. Herzberg).

'"See E.E. Lawler, 111,Motivation in Work Organizations, Brooks/Cole publishing Co., 1973, pp. 5-7.

-262-

HUMAN MOTIVATION IN THE WORK ORGANIZATION

11

"See Douglas McGregor, The Human Side of Enterprises, McGraw-Hill, 1960. pp. 47-49; Rensis Likert, The Human

Organization, McGraw-Hill, 1967.

12

See, for example, E. Wight Bakke, "The Function of Management", in E.M. Hugh-Jones (ed.) Human Relations and

Modern Management, North Holland PubL Co., 1958; Chris Argyris, Personality and Organization, Harper & Row, 1957;

Warren Bennis, Changing Organizations, McGraw-Hill, 1966; G.H. Litwin and R.A. Stringer, Jr. Motivation and Organizational Climate, Harvard Business School, 1968.

13

For a comparison of some of the characteristics between the adaptive-organic organization structure and the mechanistic-bureaucratic structure, see Ralph M. Hower and Jay W. Lorsch, "Organization Inputs," in John A. Seller, Systems Analysis

in Organizational Behavior, Irwin, 1967, p. 168.

14

See Frederick Herzberg, Bernard Mausner, and Barbara Snyderman, The Motivation to Work, Wiley, 1959, pp. 20-62,

141; Frederick Herzberg, Work and the Nature of Man, The World Publishing Co., 1966, pp. 92-129; "One More Time: How

Do You Motivate Employees?" Harvard Business Review, Jan. Feb. 1968.

15

Victor H. Vroom, Work and Motivation, Wiley, 1964, pp. 14-15, 128.

"See John Camphell, Marvin Dunnette, Edward Lawler III, and Karl Weick, Managerial Behavior, Performance, and

Effectiveness, McGraw-Hill, 1970; Anthony Biglan and Terence Mitchell, "Instrumentality Theories", and Terence Mitchell,

"Expectancy Model of Job Satisfaction, Occupational Preference and Effort: A Theoretical, Methodological and Empirical

Appraisal,"Psychology Bulletin, 82, 1974.

17

Organizational climate is a set of properties of the work environment perceived directly or indirectly by the employees.

Its important dimensions include: leadership patterns, goal-direction, size and structure of the organization, communication

networks, amount of challenge and responsibility, degree and nature of conflict, nature of reward and punishment systems,

etc. There is no unique set of organizational climate dimensions, nor is there one best value for each of those dimensions.

18

In this connection, the reader may refer to "Motivation: Good Theory Poor Application," by Joel K. Leidecker and

James J. Hall, Training and Development Journal, June 1974.

"See, for example, Paul, Robertson and Herzberg, "Job Enrichment Pays Off," Harvard Business Review, Mar.-Apr.

1969; Robert Ford, "Job Enrichment Lessons from AT & T," Harvard Business Review, Jan.-Feb. 1973; William Reif and

Fred Luthans, "Does Job Enrichment Really Pays Off?" California Management Review, Fail 1972; and J. Richard Hackman,

"Is Job Enrichment Just a Fad?" Harvard Business Review, Sept.-Oct. 1975.

2

"See Richard Walton, "How to Counter Alienation in the Plant," Harvard Business Review, Nov.-Dec. 1972.

-263-

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Performance Appraisal Essentials: A Practical GuideDa EverandPerformance Appraisal Essentials: A Practical GuideNessuna valutazione finora

- Ruth Velien Ni Nyoman Maylina Triastuti Stasya MonifaDocumento42 pagineRuth Velien Ni Nyoman Maylina Triastuti Stasya Monifahelena danNessuna valutazione finora

- HRM Hospital Unit 4Documento35 pagineHRM Hospital Unit 4nicevenuNessuna valutazione finora

- Human Resource Management: Class AssignmentDocumento15 pagineHuman Resource Management: Class AssignmentchikaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Employee Experience Index by IBMDocumento14 pagineThe Employee Experience Index by IBMJoão RibeiroNessuna valutazione finora

- Context of HRM PresentationDocumento21 pagineContext of HRM PresentationBhavi Solanki100% (1)

- TMS Final Cheat SheetDocumento2 pagineTMS Final Cheat SheetMarie GualtieriNessuna valutazione finora

- Building Internal EquityDocumento38 pagineBuilding Internal EquitySaurabh Kulkarni 23Nessuna valutazione finora

- Building Internal EquityDocumento38 pagineBuilding Internal EquityPK AAMIRNessuna valutazione finora

- Business Mrs - Rehab CH 6Documento7 pagineBusiness Mrs - Rehab CH 6mohammed mahdyNessuna valutazione finora

- APPLIED MOTIVATIONAL PRACTICES (Sanyo Sunny)Documento30 pagineAPPLIED MOTIVATIONAL PRACTICES (Sanyo Sunny)Rahul RajeshNessuna valutazione finora

- Employee MotivationDocumento4 pagineEmployee MotivationCarlMonteroyoApuyanNessuna valutazione finora

- Block 3 MS 27 Unit 2Documento13 pagineBlock 3 MS 27 Unit 2Suparna2Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Employee Experience IndexDocumento16 pagineThe Employee Experience Indexuday_kendhe9005100% (1)

- Applied Performance Practices2Documento11 pagineApplied Performance Practices2Marvielyn Mercado MorilloNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 7-Step1-4Documento3 pagineChapter 7-Step1-4punzalanalvin526Nessuna valutazione finora

- Employees' Job Satisfaction in Vietnamese Organization: Group 1Documento16 pagineEmployees' Job Satisfaction in Vietnamese Organization: Group 1Dương HồngNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 7Documento2 pagineChapter 7Shairrah SainzNessuna valutazione finora

- 11 - Performance Evaluation and Appraisal Feedback - SEKITODocumento7 pagine11 - Performance Evaluation and Appraisal Feedback - SEKITOMika SaldanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Module 3 HRMDocumento27 pagineModule 3 HRMRajesh ChedaNessuna valutazione finora

- Hbo Midterm2Documento5 pagineHbo Midterm2Michelle Go100% (2)

- Mmfa13 - Human Resource: Compensation ManagementDocumento15 pagineMmfa13 - Human Resource: Compensation ManagementShan MiawNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 8Documento10 pagineChapter 8Peter ImmanuelNessuna valutazione finora

- Motivation: Processes and TheoriesDocumento17 pagineMotivation: Processes and TheoriesramanmaNessuna valutazione finora

- IO Reviewer Chapter 9Documento4 pagineIO Reviewer Chapter 9luzille anne alertaNessuna valutazione finora

- MotivationDocumento7 pagineMotivationrajat1311Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lunenburg, Fred C Motivating by Enriching Jobs IJMBA V15 N1 2011Documento11 pagineLunenburg, Fred C Motivating by Enriching Jobs IJMBA V15 N1 2011HafsaNessuna valutazione finora

- Say Stay or Strive Health AonDocumento6 pagineSay Stay or Strive Health AonDoris YanNessuna valutazione finora

- HRM - Unit 2 - PPT - VJDocumento14 pagineHRM - Unit 2 - PPT - VJVijay prasadNessuna valutazione finora

- HRM - Unit 2 - PPT - VJDocumento14 pagineHRM - Unit 2 - PPT - VJVijay prasadNessuna valutazione finora

- MPO PresentationDocumento20 pagineMPO Presentationrajat1311Nessuna valutazione finora

- Motivation - Applied Performance PracticesDocumento12 pagineMotivation - Applied Performance Practicesphamhuynh nhulyNessuna valutazione finora

- Compensation Policy - Chapter 02 Compensation Administration Process Principles of Administration of CompensationDocumento6 pagineCompensation Policy - Chapter 02 Compensation Administration Process Principles of Administration of CompensationSanam PathanNessuna valutazione finora

- Tiwari Unit 4Documento13 pagineTiwari Unit 4DUSHYANT KUMAR SINGHNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 3 Workforce FocusDocumento24 pagineChapter 3 Workforce FocuscynangelaNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 7Documento3 pagineChapter 7Shairrah SainzNessuna valutazione finora

- Engineering SubjectsDocumento29 pagineEngineering Subjectseutikol69Nessuna valutazione finora

- Herzberg's Dual Factor TheoryDocumento18 pagineHerzberg's Dual Factor TheoryShahida SshamsNessuna valutazione finora

- S&C 2Documento25 pagineS&C 2Mustafa LakhaniNessuna valutazione finora

- CH 5 - Compensation MGTDocumento28 pagineCH 5 - Compensation MGTGetnat BahiruNessuna valutazione finora

- Motivation: From Concepts To Applications: "Money Is Better Than Poverty, If Only For Financial Reasons"Documento24 pagineMotivation: From Concepts To Applications: "Money Is Better Than Poverty, If Only For Financial Reasons"masoodNessuna valutazione finora

- Week012 Staffing2Documento9 pagineWeek012 Staffing2Joana MarieNessuna valutazione finora

- Paper 1 Unit 7Documento7 paginePaper 1 Unit 7Ruchi MishraNessuna valutazione finora

- HR Thoeries at A GlanceDocumento4 pagineHR Thoeries at A GlanceZahra RahimNessuna valutazione finora

- Nature of Job SatisfactionDocumento17 pagineNature of Job SatisfactionParas Jain100% (4)

- HRM NotesDocumento9 pagineHRM NotesElla MaeNessuna valutazione finora

- 10bus 2Documento4 pagine10bus 2yebinNessuna valutazione finora

- Final Exam Human Resource ManagementDocumento10 pagineFinal Exam Human Resource ManagementIvy PulidoNessuna valutazione finora

- Job and JOB AnalysisDocumento38 pagineJob and JOB Analysisebrar totoNessuna valutazione finora

- Motivation: From Concepts To Applications: SevenDocumento33 pagineMotivation: From Concepts To Applications: SevenAnkur LohanNessuna valutazione finora

- HR Systems Related To Performance Management: Managing Employee Performance and Performance AppraisalDocumento16 pagineHR Systems Related To Performance Management: Managing Employee Performance and Performance Appraisalerine5995Nessuna valutazione finora

- TeamDocumento4 pagineTeamjamilepscuaNessuna valutazione finora

- Human Resource Management: Supervised By: MR - Ait CherkiDocumento40 pagineHuman Resource Management: Supervised By: MR - Ait CherkiHiba jerraNessuna valutazione finora

- Mo Exam NotesDocumento20 pagineMo Exam Notessherylphua87Nessuna valutazione finora

- ABM11 - Organization and Management - Q2 - W3-4Documento5 pagineABM11 - Organization and Management - Q2 - W3-4Emmanuel Villeja LaysonNessuna valutazione finora

- (PSY 225) 4th Examination ReviewerDocumento7 pagine(PSY 225) 4th Examination Reviewermariyvonne01Nessuna valutazione finora

- Faiza - 1334 - 16064 - 2 - Lecture 3 - Organization - Individual Relations and RetentionsDocumento20 pagineFaiza - 1334 - 16064 - 2 - Lecture 3 - Organization - Individual Relations and RetentionsUrooj MustafaNessuna valutazione finora

- Motivation: From Concepts To Applications: SevenDocumento33 pagineMotivation: From Concepts To Applications: SevenpRiNcE DuDhAtRaNessuna valutazione finora

- Human Behavior in Organization: "Motivation"Documento36 pagineHuman Behavior in Organization: "Motivation"Mark Kevin SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Reward Management Internal and External Equity Spirit of New PayDocumento40 pagineReward Management Internal and External Equity Spirit of New PayJulia LegaspiNessuna valutazione finora

- Cultural Tourism in Gjirokastra: Mimoza Kotollaku Magdalena Margariti, MSCDocumento23 pagineCultural Tourism in Gjirokastra: Mimoza Kotollaku Magdalena Margariti, MSCandrawes222Nessuna valutazione finora

- 3 Liesure and Entertainment InsightsDocumento4 pagine3 Liesure and Entertainment Insightsandrawes222Nessuna valutazione finora

- Tourism and Globalization in The Arab WorldDocumento12 pagineTourism and Globalization in The Arab WorldWiwik RachmarwiNessuna valutazione finora

- Tourism and Globalization in The Arab WorldDocumento12 pagineTourism and Globalization in The Arab WorldWiwik RachmarwiNessuna valutazione finora

- 3 The Impact of Cultural Distance On Local ResidentsDocumento18 pagine3 The Impact of Cultural Distance On Local Residentsandrawes222Nessuna valutazione finora

- 3 Culture - Workstyles - DubaiDocumento7 pagine3 Culture - Workstyles - Dubaiandrawes222Nessuna valutazione finora

- Job - WALK - in International Non Voice Process at Mphasis, Bangalore - Bengaluru - Bangalore - MphasiS Limited - 0 Years of Experience - Jobs IndiaDocumento3 pagineJob - WALK - in International Non Voice Process at Mphasis, Bangalore - Bengaluru - Bangalore - MphasiS Limited - 0 Years of Experience - Jobs IndiaMohan LalNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction of Apple. Inc.: (Nature and Experiences)Documento11 pagineIntroduction of Apple. Inc.: (Nature and Experiences)Vi AtilanoNessuna valutazione finora

- Job Order PracticeDocumento3 pagineJob Order PracticeAnna Mae SanchezNessuna valutazione finora

- English AssignmentDocumento5 pagineEnglish AssignmentMira AmiraNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 2 TestDocumento4 pagineChapter 2 TestNaved Naddie100% (1)

- Assignment Safety Report WALTON Factory Mahmudul HaqueDocumento28 pagineAssignment Safety Report WALTON Factory Mahmudul Haquepunter07Nessuna valutazione finora

- CourseDocumento3 pagineCourseKNessuna valutazione finora

- Memorandum of Association & Articles of Association OFDocumento25 pagineMemorandum of Association & Articles of Association OFAmeer SiddiquiNessuna valutazione finora

- Factors Influencing Job Satisfaction of The Employees of Tannery Industry in BangladeshDocumento6 pagineFactors Influencing Job Satisfaction of The Employees of Tannery Industry in BangladeshRitesh shresthaNessuna valutazione finora

- SM5-Case 10-Vick's Pizza CorpDocumento3 pagineSM5-Case 10-Vick's Pizza CorpMohamed ZakaryaNessuna valutazione finora

- Eric Weinstein Migration For The Benefit of All International Labour Review Vol 141 2002 No 3Documento29 pagineEric Weinstein Migration For The Benefit of All International Labour Review Vol 141 2002 No 3Colin DuffyNessuna valutazione finora

- ITB 07 - Human Resource ManagementDocumento24 pagineITB 07 - Human Resource ManagementNeesha NazNessuna valutazione finora

- Resume Construction PDFDocumento8 pagineResume Construction PDFafiwhwlwx100% (2)

- US Social Security Form (Ssa-7050) : Wage Earnings CorrectionDocumento4 pagineUS Social Security Form (Ssa-7050) : Wage Earnings CorrectionMax PowerNessuna valutazione finora

- Survey ON Status of Coir Industry in Kerala: The ConsultantsDocumento176 pagineSurvey ON Status of Coir Industry in Kerala: The ConsultantsShameerNessuna valutazione finora

- ROHITDocumento66 pagineROHITRohit John MambalilNessuna valutazione finora

- 112 HSE Interview Questions and AnswersDocumento14 pagine112 HSE Interview Questions and AnswersMuhammad Ramzan100% (3)

- HR Planning For Alignment and Change: School of Business Marketing Ms - KomlavathiDocumento19 pagineHR Planning For Alignment and Change: School of Business Marketing Ms - KomlavathiKomlavathiNessuna valutazione finora

- Royal Plant Workers V Coca Cola BottlersDocumento4 pagineRoyal Plant Workers V Coca Cola BottlersinvictusincNessuna valutazione finora

- Accenture Creating Talent in Aerospace and Defense RevDocumento34 pagineAccenture Creating Talent in Aerospace and Defense RevArchana SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Cover LetterDocumento3 pagineCover LetterTcer ItaNessuna valutazione finora

- ATOS, ARK, Eugenics, One Page Flier.Documento1 paginaATOS, ARK, Eugenics, One Page Flier.Cazzac111Nessuna valutazione finora

- Assignments Part I Papers of ISTD Diploma Programme, 2012 January BatchDocumento20 pagineAssignments Part I Papers of ISTD Diploma Programme, 2012 January Batchrukmanbgh12100% (1)

- Job Satisfaction Among Long Term Care Staff Bureaucracy Isn T Always BadDocumento11 pagineJob Satisfaction Among Long Term Care Staff Bureaucracy Isn T Always BadKat NavarroNessuna valutazione finora

- Employees' Provident Funds and Miscellaneous Provisions Act, 1952 (EPF&MP Act, 1952)Documento17 pagineEmployees' Provident Funds and Miscellaneous Provisions Act, 1952 (EPF&MP Act, 1952)bhargaviNessuna valutazione finora

- Operations Manager or Director of Operations or Warehouse ManageDocumento3 pagineOperations Manager or Director of Operations or Warehouse Manageapi-121367305Nessuna valutazione finora

- Labor Bar Syllabus 2020Documento13 pagineLabor Bar Syllabus 2020Ronaldo ValladoresNessuna valutazione finora

- Preventing SH at WORKPLACEDocumento46 paginePreventing SH at WORKPLACEarpitNessuna valutazione finora

- Research ProjectDocumento55 pagineResearch ProjectRio De LeonNessuna valutazione finora

- Papua New Guinea - Assessment of Agricultural Information NeedsDocumento64 paginePapua New Guinea - Assessment of Agricultural Information NeedsJan GoossenaertsNessuna valutazione finora

- Spark: How to Lead Yourself and Others to Greater SuccessDa EverandSpark: How to Lead Yourself and Others to Greater SuccessValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (132)

- Summary of Noah Kagan's Million Dollar WeekendDa EverandSummary of Noah Kagan's Million Dollar WeekendValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- The First Minute: How to start conversations that get resultsDa EverandThe First Minute: How to start conversations that get resultsValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (57)

- The Coaching Habit: Say Less, Ask More & Change the Way You Lead ForeverDa EverandThe Coaching Habit: Say Less, Ask More & Change the Way You Lead ForeverValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (186)

- Scaling Up: How a Few Companies Make It...and Why the Rest Don't, Rockefeller Habits 2.0Da EverandScaling Up: How a Few Companies Make It...and Why the Rest Don't, Rockefeller Habits 2.0Valutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- Coach the Person, Not the Problem: A Guide to Using Reflective InquiryDa EverandCoach the Person, Not the Problem: A Guide to Using Reflective InquiryValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (64)

- The 7 Habits of Highly Effective PeopleDa EverandThe 7 Habits of Highly Effective PeopleValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (2564)

- How to Talk to Anyone at Work: 72 Little Tricks for Big Success Communicating on the JobDa EverandHow to Talk to Anyone at Work: 72 Little Tricks for Big Success Communicating on the JobValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (36)

- Transformed: Moving to the Product Operating ModelDa EverandTransformed: Moving to the Product Operating ModelValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1)

- Billion Dollar Lessons: What You Can Learn from the Most Inexcusable Business Failures of the Last Twenty-five YearsDa EverandBillion Dollar Lessons: What You Can Learn from the Most Inexcusable Business Failures of the Last Twenty-five YearsValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (52)

- Leadership Skills that Inspire Incredible ResultsDa EverandLeadership Skills that Inspire Incredible ResultsValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (11)

- Only the Paranoid Survive: How to Exploit the Crisis Points That Challenge Every CompanyDa EverandOnly the Paranoid Survive: How to Exploit the Crisis Points That Challenge Every CompanyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (122)

- How to Lead: Wisdom from the World's Greatest CEOs, Founders, and Game ChangersDa EverandHow to Lead: Wisdom from the World's Greatest CEOs, Founders, and Game ChangersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (95)

- The Little Big Things: 163 Ways to Pursue ExcellenceDa EverandThe Little Big Things: 163 Ways to Pursue ExcellenceNessuna valutazione finora

- 25 Ways to Win with People: How to Make Others Feel Like a Million BucksDa Everand25 Ways to Win with People: How to Make Others Feel Like a Million BucksValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (36)

- The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: 30th Anniversary EditionDa EverandThe 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: 30th Anniversary EditionValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (337)

- The Effective Executive: The Definitive Guide to Getting the Right Things DoneDa EverandThe Effective Executive: The Definitive Guide to Getting the Right Things DoneValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (469)

- The 12 Week Year: Get More Done in 12 Weeks than Others Do in 12 MonthsDa EverandThe 12 Week Year: Get More Done in 12 Weeks than Others Do in 12 MonthsValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (411)

- Radical Candor by Kim Scott - Book Summary: Be A Kickass Boss Without Losing Your HumanityDa EverandRadical Candor by Kim Scott - Book Summary: Be A Kickass Boss Without Losing Your HumanityValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (40)

- Work the System: The Simple Mechanics of Making More and Working Less (4th Edition)Da EverandWork the System: The Simple Mechanics of Making More and Working Less (4th Edition)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (23)

- 7 Principles of Transformational Leadership: Create a Mindset of Passion, Innovation, and GrowthDa Everand7 Principles of Transformational Leadership: Create a Mindset of Passion, Innovation, and GrowthValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (52)

- Management Mess to Leadership Success: 30 Challenges to Become the Leader You Would FollowDa EverandManagement Mess to Leadership Success: 30 Challenges to Become the Leader You Would FollowValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (27)

- Transformed: Moving to the Product Operating ModelDa EverandTransformed: Moving to the Product Operating ModelValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1)

- The Introverted Leader: Building on Your Quiet StrengthDa EverandThe Introverted Leader: Building on Your Quiet StrengthValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (35)

- The Power of People Skills: How to Eliminate 90% of Your HR Problems and Dramatically Increase Team and Company Morale and PerformanceDa EverandThe Power of People Skills: How to Eliminate 90% of Your HR Problems and Dramatically Increase Team and Company Morale and PerformanceValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (22)

- Work Stronger: Habits for More Energy, Less Stress, and Higher Performance at WorkDa EverandWork Stronger: Habits for More Energy, Less Stress, and Higher Performance at WorkValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (12)

- Escaping the Build Trap: How Effective Product Management Creates Real ValueDa EverandEscaping the Build Trap: How Effective Product Management Creates Real ValueValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (71)

- The E-Myth Revisited: Why Most Small Businesses Don't Work andDa EverandThe E-Myth Revisited: Why Most Small Businesses Don't Work andValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (709)

- The 12 Week Year: Get More Done in 12 Weeks than Others Do in 12 MonthsDa EverandThe 12 Week Year: Get More Done in 12 Weeks than Others Do in 12 MonthsValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (90)