Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Memorandum Opinion and Order

Caricato da

Albuquerque JournalCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Memorandum Opinion and Order

Caricato da

Albuquerque JournalCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Case 1:16-cv-00252-KG-KBM Document 132 Filed 07/29/16 Page 1 of 14

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEW MEXICO

COALITION OF CONCERNED CITIZENS

TO MAKEARTSMART, an Unincorporated

Association, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION OF

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION,

an Agency of the United States, et al.,

Defendants.

Civ. No. 16-252 KG/KBM

Consolidated With

Civ. No. 16-354 KG/KBM

and

MARIA BAUTISTA, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

FEDERAL TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION OF

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION,

an Agency of the United States, et al.,

Defendants.

MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER

This matter comes before me upon Plaintiffs Coalition to Make ART Smart, et al.s

Motion for a Preliminary Injunction and Bautista Plaintiffs Motion for Preliminary Injunction

(collectively, Motions for Preliminary Injunction). (Docs. 45 and 48). Both Motions are

completely briefed. (Docs. 49, 50, 68, 70, 72, 79, 80, 82, 83). I held a three-day hearing on the

Motions for Preliminary Injunction on July 27-29, 2016.

Case 1:16-cv-00252-KG-KBM Document 132 Filed 07/29/16 Page 2 of 14

In applying for a Federal Transit Authority (FTA) Small Starts grant to fund, in part, the

Albuquerque Rapid Transit (ART) project, the City applied for a documented categorical

exclusion (CE). A CE would exclude the City of Albuquerque (City) from engaging in the

environmental assessment or environmental impact statement processes under the National

Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). The Coalition of Concerned Citizens to Make ART Smart

Plaintiffs (Coalition Plaintiffs) contest the FTAs approval of the Citys application for a CE as a

violation of NEPA.

Also, in reviewing a Small Starts application, the FTA is required under Section 106 of

the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) to identify historic properties that are eligible for

the National Register listing, assess the projects effects on those properties, and avoid or

mitigate any adverse effects. 36 C.F.R. 800.2 and 800.4-800.6. In this case, the FTA, in

consultation with the State Historic Preservation Officer (SHPO), concluded that there would be

no adverse effects to the area of potential effect (APE) related to the ART project. The Coalition

and Bautista Plaintiffs (collectively, Plaintiffs) contest the FTAs finding of no adverse effect as

a violation of the NHPA.1

Plaintiffs now seek a preliminary injunction to halt the start of the ART project while the

Court considers the merits of their lawsuit. Prior to the evidentiary hearing, I reviewed the

Preliminary Administrative Record (ABQ PAR) and briefs. Furthermore, I have considered

testimony of witnesses and the argument of counsel.

If or when the ART project is constructed and put into operation, there may be a day

when I will utilize it and fully realize everything the system now is envisioned to be: a speedy,

convenient, environmentally smart transportation system that, in addition, spurs necessary

1

Plaintiffs have brought other claims against Defendants, but Plaintiffs focused on the NEPA

and NHPA claims during the hearing on the Motions for Preliminary Injunction.

2

Case 1:16-cv-00252-KG-KBM Document 132 Filed 07/29/16 Page 3 of 14

economic development into an area of Albuquerque that needs it. Today, however, and from a

personal standpoint, I cannot be certain that I buy in. It means changes to an area of

Albuquerque that I may not be ready to accept. But to resolve this matter, I must set aside my

personal opinion and employ the correct legal standards. Indeed, this Court is bound by those

standards. And after objectively applying the correct legal standards and considering all the

aforementioned submissions, I must DENY the motions.

A. Standards

1. Preliminary Injunction

To obtain a preliminary injunction under Fed. R. Civ. P. 65, the moving party

bears the burden of showing: (1) a substantial likelihood of success on the merits; (2) irreparable

harm unless the injunction is issued; (3) the threatened injury outweighs the harm that the

preliminary injunction may cause the opposing party; and (4) the injunction, if issued, will not

adversely affect the public interest. Fed. Lands Legal Consortium ex rel. Robart Estate v. United

States, 195 F.3d 1190, 1194 (10th Cir. 1999) (citing Chemical Weapons Working Group, Inc. v.

United States Dep't of the Army, 111 F.3d 1485, 1489 (10th Cir.1997)). As a preliminary

injunction is an extraordinary remedy, the [requesting partys] right to relief must be clear and

unequivocal. Prairie Band of Potawatomi Indians v. Pierce, 253 F.3d 1234, 1246 (10th Cir.

2001) (citing SCFC ILC, Inc. v. Visa USA, Inc., 936 F.2d 1096, 1098 (10th Cir.1991)).

2. The Administrative Procedures Act (APA)

Both the NEPA and NHPA claims are brought under the APA. Under the APA, any

person suffering legal wrong because of agency action, or adversely affected or aggrieved by

agency action within the meaning of a relevant statute, is entitled to judicial review thereof. 5

Case 1:16-cv-00252-KG-KBM Document 132 Filed 07/29/16 Page 4 of 14

U.S.C. 702. The reviewing court shall set aside the agency action under 5 U.S.C. 706(2)(A)

if it is arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, or otherwise not in accordance with law.

Under 706(2)(A) of the APA, an agency's action is arbitrary and capricious if the

agency ... entirely failed to consider an important aspect of the problem, offered an explanation

for its decision that runs counter to the evidence before the agency, or is so implausible that it

could not be ascribed to a difference in view or the product of agency expertise. Utah Envtl.

Cong. v. Bosworth, 443 F.3d 732, 739 (10th Cir. 2006) (quoting Motor Vehicle Mfrs. Ass'n v.

State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins. Co., 463 U.S. 29, 43 (1983)). Likewise, an agency's decision is

arbitrary and capricious if the agency failed to base its decision on consideration of the relevant

factors, or if there has been a clear error of judgment on the agency's part. Id.

When courts consider such challenges, an agency's decision is entitled to a presumption

of regularity, and the challenger bears the burden of persuasion. San Juan Citizens Alliance v.

Stiles, 654 F.3d 1038, 1045 (10th Cir.2011) (citations omitted). The Courts deferential review

is especially strong where the challenged decisions involve technical or scientific matters within

the agency's area of expertise. Utah Envtl. Cong. v. Russell, 518 F.3d 817, 824 (10th Cir.2008)

(citing Marsh v. Or. Natural Res. Council, 490 U.S. 360, 378 (1989)); see also San Juan Citizens

Alliance v. Stiles, 654 F.3d 1038, 1045 (10th Cir. 2011) ([W]hen specialists express conflicting

views, an agency must have discretion to rely on the reasonable opinion of its own qualified

experts, even if, as an original matter, a court might find contrary views more persuasive.

(quotations omitted)). The Court recognizes that the arbitrary and capricious standard along with

the deference to the agency impose a high barrier for Plaintiffs to clear in order to show a

likelihood of success on the merits of the NEPA and NHPA claims. Indeed, for Plaintiffs, this is

an unavoidable tall order.

Case 1:16-cv-00252-KG-KBM Document 132 Filed 07/29/16 Page 5 of 14

B. Requirements for a Preliminary Injunction

1. Likelihood of Success on the Merits

a. NEPA Claim

Class II actions are actions which do not individually or cumulatively have a significant

environmental effect and are excluded from EIS or EA requirements, i.e., they are categorically

excluded in a CE. 23 C.F.R. 771.115(b). A CE designation is appropriate if an action does not

involve significant environmental impacts. 23 C.F.R. 771.118(a). More specifically, a CE

designation is appropriate if an action does not have a significant impact on natural, cultural, and

historical resources or does not significantly impact travel patterns. Id. An action which the

FTA would normally consider a CE but could involve unusual circumstances will require the

FTA, in cooperation with the applicant, to conduct environmental studies to determine if the CE

classification is proper. Id. at 771.118(b). Such an unusual circumstance includes when there

is [s]ubstantial controversy on environmental grounds. Id. at 771.118(b)(2).

When examining an agencys CE determination under NEPA, the Court must heed the

Tenth Circuits explanation of an agencys obligations under NEPA:

NEPA places upon federal agencies the obligation to consider every significant aspect of

the environmental impact of a proposed action. Baltimore Gas & Elec. Co. v. Natural

Res. Defense Council, 462 U.S. 87, 97, 103 S.Ct. 2246, 76 L.Ed.2d 437 (1983). It also

ensures that an agency will inform the public that it has considered environmental

concerns in its decision-making process. Id. The Act does not require agencies to

elevate environmental concerns over other appropriate considerations, however; it

requires only that the agency take a hard look at the environmental consequences

before taking a major action. Id. In other words, it prohibits uninformed-rather than

unwise-agency action. Custer County Action Ass'n. v. Garvey, 256 F.3d 1024, 1034

(10th Cir.2001). The role of the courts in reviewing compliance with NEPA is simply to

ensure that the agency has adequately considered and disclosed the environmental impact

of its actions and that its decision is not arbitrary and capricious. Baltimore Gas &

Elec., 462 U.S. at 97-98, 103 S.Ct. 2246.

Utah Shared Access All. v. U.S. Forest Serv., 288 F.3d 1205, 1207-08 (10th Cir. 2002).

5

Case 1:16-cv-00252-KG-KBM Document 132 Filed 07/29/16 Page 6 of 14

Plaintiffs argue first that the FTA did not take a hard look at the Citys CE application

and that the FTAs decision to approve the CE application was arbitrary and capricious. A brief

approval of a CE application, like in this case, does not necessarily constitute a failure to take a

hard look. Defendants cite Wilderness Watch & Pub. Employees for Envtl. Responsibility v.

Mainella, 375 F.3d 1085, 1095 (11th Cir. 2004) (Documentation of reliance on a categorical

exclusion need not be detailed or lengthy. It need only be long enough to indicate to a reviewing

court that the agency indeed considered whether or not a categorical exclusion applied and

concluded that it did.). In fact, upon questioning of Defendant Donald Koski, Director of

Planning and Program Development of Region VI of the FTA, Koski indicated that his staff

reviewed a draft of the CE application, communicated with the City regarding its project

development request, consulted with the SHPO, and reviewed the final CE application as did

Koski. FTA Exs. 1-5. These actions demonstrate that the FTA took the required hard look at

the CE application.

Plaintiffs also argue that the FTAs action was arbitrary and capricious because the Citys

CE application did not consider economic impacts on businesses or traffic issues such as

congestion and diversion of traffic to neighborhoods adjacent to Central Avenue. The City,

however, did provide the FTA with a business access technical supplement and a traffic

assessment technical supplement in response to the CE worksheets request for information

related to economic environment and traffic patterns. (Doc. 54-1) at 6-7. Those supplements

indicate that no business will lose access, congestion will be minimalized with signalized left and

u-turns, and that diversion into neighborhoods would amount to 250 vehicles daily. The

diversion number is supported by a traffic engineers expert opinion. I note that although traffic

congestion will increase at intersections in 2035, the CE application only required a traffic

Case 1:16-cv-00252-KG-KBM Document 132 Filed 07/29/16 Page 7 of 14

congestion projection to 2017. Even with an increase in traffic in 2035, the City provided

mitigation actions to alleviate that congestion. I conclude that the FTA considered relevant

factors, like economic environment and traffic patterns. The FTAs actions would only be

arbitrary and capricious if it entirely failed to consider those factors. I cannot find that the

FTA entirely failed here. Moreover, the Court presumes that the FTAs action was regular, a

presumption Plaintiffs did not rebut. Finally, the Court gives strong deference to the FTAs

technical expertise in this matter.

Next, Plaintiffs argue that because there was a substantial controversy on environmental

grounds, the FTA should not have approved the CE application. It is quite clear to me there is

opposition to this project. Opposition, however, does not necessarily mean a substantial

controversy. As one court explained,

[The mere existence of opposition does not trigger the [agency's] duty to prepare an

environmental review. West Houston Air Committee v. FAA, 784 F.2d 702, 705 (5th

Cir.1986). Courts long ago rejected the suggestion that controversial must necessarily

be equated with opposition. North Carolina v. FAA, 957 F.2d 1125, 113334 (4th

Cir.1992). Otherwise, opposition, and not the reasoned analysis set forth in the

environmental assessment, would determine whether a[ ][CE] would have to be

prepared. Id. Thus, the outcome would be governed by a heckler's veto. North

Carolina, 957 F.2d at 1134 (quoting River Road Alliance, Inc. v. Corps of Eng'rs of

United States Army, 764 F.2d 445, 451 (7th Cir.1985)); see also Friends of Richards

Gebaur Airport v. FAA, 251 F.3d 1178, 1187 (8th Cir.2001) (upholding CE based in part

on determination that 65 letters opposing the project [most of which did not voice

environmental concerns] did not constitute a substantial controversy on environmental

grounds).

Aquifer Guardians in Urban Areas v. Fed. Highway Admin., 779 F. Supp. 2d 542, 572 (W.D.

Tex. 2011).

The CE application includes a detailed summary of comments, including negative

comments, but those comments do not suggest substantial controversy on environmental

grounds. General concerns and even economic impacts are not environmental grounds for

purposes of assessing public controversy. See Hells Canyon Pres. Council v. Jacoby, 9 F. Supp.

7

Case 1:16-cv-00252-KG-KBM Document 132 Filed 07/29/16 Page 8 of 14

2d 1216, 1242 (D. Or. 1998) (general remarks regarding concerns not enough to establish

substantial controversy). Moreover, the negative comments did not identify a substantial

controversy over the size, nature or effect of the environmental impacts. See Hillsdale Envtl.

Loss Prevention, Inc. v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 702 F.3d 1156, 1181 (10th Cir. 2012)

(Controversy in this context does not mean opposition to a project, but rather a substantial

dispute as to the size, nature, or effect of the action.) (citation omitted). Instead, many people

complained about cost, access to businesses, lost parking, removal of the median, and preferred

alignments. These complaints do not meet the legal test.

b. NHPA Claim

Plaintiffs complain that the FTA defined the APE too narrowly and argue that the ART

project will directly or indirectly cause alterations in the character or use of historic properties

beyond just the bus stations. See 36 C.F.R. 800.16(d). In addition, Plaintiffs argue that the

FTA ignored the fact that the ART project will introduce visual, atmospheric or audible

elements that will diminish the historical nature of properties. See 36 C.F.R. 800.5(a)(2)(v).

Plaintiffs contend that the City must consider the cumulative impact of ART in determining

whether ART will adversely affect historic resources. 36 C.F.R. 800.5(a)(1) (Adverse effects

may include reasonably foreseeable effects caused by the undertaking that may occur later in

time, be farther removed in distance or be cumulative.).

The FTA, in consultation with the SHPO, defined the APE and considered potential

effects of ART, and so concluded that they would not have an adverse effect on any historic

resource. Moreover, the eclectic nature of Central Avenue does not lend itself to being

designated a historic district. As Jeff Fredine testified, historic districts are comprised of a

similarly aged and designed cluster of properties. This testimony is in line with David

Case 1:16-cv-00252-KG-KBM Document 132 Filed 07/29/16 Page 9 of 14

Kammers 2003 study, relied on by the City in its CE application: Route 66, as an individual

property type, through the current project area does not retain enough integrity to convey its

historic significance and is recommended not eligible to the National Register of Historic Places

(NRHP). ABQ PAR 03011-12. Although, Kammer states that the Historic Preservation

Department and others should collectively address the possibility of nominating Route 66related historic districts in urban areas including in Albuquerque, that possibility has not been

addressed and planners such as Fredine continue to concur with Kammers conclusion that Route

66 in Albuquerque, though historic and much loved by Albuquerqueans and tourists alike, would

not be eligible for inclusion on the NRHP. Route 66 Resurvey Pt. 2, pg. 19-20. Indirect effects,

like a change in the feeling or setting of Central Avenue after the ART project is built, would

also not necessarily affect the historic integrity of Central Avenue when one considers the lack of

cohesive design in properties.

Plaintiffs also note that the FTA did not provide the SHPO with the Citys traffic study.

See Pueblo of Sandia v. United States, 50 F.3d 856, 862 (10th Cir. 1995) (Affording the SHPO

an opportunity to offer input on potential historic properties would be meaningless unless the

SHPO has access to available, relevant information.). The SHPO knew what the ART design

would be, including median stations. Plaintiffs, however, have not sufficiently established how a

study showing a diversion of 250 cars per day and possible increased congestion at intersections

in 2035 would affect the SHPOs decision, which was based on a narrow APE and was

concerned with visual issues.

In addition, Plaintiffs contend that the FTA failed to engage the public or seek public

comment as required by the NHPA. The regulations do not specify the form of public outreach

required under NHPA, but do state that the need for public outreach can be adjusted to account

Case 1:16-cv-00252-KG-KBM Document 132 Filed 07/29/16 Page 10 of 14

for the nature and complexity of the undertaking and its effects on historic properties. 36

C.F.R. 800.2(d)(1). The City, nonetheless, conducted public outreach which provided an

opportunity to allow comment under the NHPA. See 36 C.F.R. 800.2(d)(3).

(The agency official may use the agency's procedures for public involvement under the National

Environmental Policy Act or other program requirements in lieu of public involvement

requirements . , if they provide adequate opportunities for public involvement consistent with

this subpart.).

Michael Riordan, City Chief Operations Officer, testified the outreach included numerous

one-on-one contacts with the public, door hangers, neighborhood meetings, other public

meetings, and various other modes of outreach. From the testimony elicited at the hearing, it is

clear that some people did not get the word. Many of those that did, nevertheless, do not believe

that they were heard. And those that commented, believed they were ignored. But what also is

clear from the testimony and the record is that the Citys submission to the FTA included

sizeable numbers of comments. The FTA could conclude from the CE application that the City

engaged in public outreach which would have included comment required by the NHPA.

The Court cannot say that the FTAs decision to rely on the SHPOs concurrence as to

the scope of the APE and ultimate no-adverse effect conclusion was a clear error of judgment or

that the FTA entirely failed to consider relevant information. Consequently, the FTAs NHPA

determination was not arbitrary and capricious.

2. Irreparable Harm

The Tenth Circuit has held that harm to the environment may be presumed when an

agency fails to comply with the required NEPA procedure. Davis v. Mineta, 302 F.3d 1104,

1115 (10th Cir. 2002). However, plaintiffs must still make a specific showing that the

10

Case 1:16-cv-00252-KG-KBM Document 132 Filed 07/29/16 Page 11 of 14

environmental harm results in irreparable injury to their specific environmental interests. Id. A

plaintiff must show he will suffer an injury that is not merely serious or substantial but

certain, great, actual and not theoretical. Vill. of Logan v. U.S. Dep't of Interior, 577 F. App'x

760, 766 (10th Cir. 2014).

Plaintiffs, in this case, have presented evidence that businesses and neighborhoods will be

harmed by traffic congestion, safety issues, aesthetic and cultural loss, and loss of business.

Indeed, testimony from witnesses Steve Paternoster, Anthony Anella, and Buck Buckner, for

example, suggests a loss of business as a result of ART. However, Plaintiffs have not

demonstrated that the asserted harms are irreparable. The City states in its briefing that the ART

lanes could be redesignated as general use lanes without much trouble. Moreover, economic

injuries are not irreparable, because they are typically compensable with monetary damages. See

Heideman v. S. Salt Lake City, 348 F.3d 1182, 1189 (10th Cir. 2003) (It is also well settled that

simple economic loss usually does not, in and of itself, constitute irreparable harm; such losses

are compensable by monetary damages.).

Furthermore, the evidence shows any harm will also not be certain or great. No

business will close and at least one lane of Central will be open during construction. Once ART

is built, left-hand turns will be restricted but it is not expected they will not prevent customer

access. Moreover, the evidence indicates that over all access will improve with ART. The

witness testimony about business decline, while sincere, does not meet the legal test: Plaintiffs

have not provided any specific numbers or hard projections, for example, to show how much

business will be lost. Also, any loss of foot traffic during construction would be temporary and

foot traffic is expected to actually increase after ART is built due to improved streetscape. In

11

Case 1:16-cv-00252-KG-KBM Document 132 Filed 07/29/16 Page 12 of 14

addition, the City will implement several mitigation actions during construction to minimize

impact such as construction notices, low-or no-interest loans, and business consultants.

In addition, conclusory assertions of aesthetic harm are not sufficient to establish

irreparable harm. See Vill. of Logan, 577 F. App'x at 767 (Logan makes no attempt to appraise

this court of any evidence showing what aesthetic damage will occur, where it will occur, how it

will occur, or when it will occurit merely posits that such harm will result. Such ipse dixit,

however, is an insufficient basis to enjoin a project.).

Finally, I note that, as Judge Browning stated, the invocation of an environmental statute

such as NEPA does not alter these traditional rules for injunctive relief, and there is no

presumption that an injunction automatically follows if there is any violation of an

environmental statute. Cty. of Los Alamos v. U.S. Dep't of Energy, 2006 WL 1308305, at *8

(D.N.M. Jan. 13, 2006) (citing Amoco Prod. Co. v. Village of Gambell, 480 U.S. 531, 542

(1987); Weinberger v. Romero-Barcelo, 456 U.S. 305, 313 (1982)). Plaintiffs must demonstrate

a significant risk of environmental harm [that would] result[] in irreparable injury to their

specific environmental interests. Davis, 302 F.3d at 1115. The operative word here is

significant. Moreover, economic injuries are not environmental injuries. See Moyle

Petroleum v. LaHood, 969 F. Supp. 2d 1332, 1336 (D. Utah 2013). A presumption of

environmental harm also only applies in cases where NEPA violations are likely to have

occurred. Vill. of Logan, 577 F. App'x at 767. As discussed supra, Plaintiffs have not shown

that NEPA violations likely occurred. In sum, Plaintiffs have not satisfied the irreparable harm

requirement for a preliminary injunction.

12

Case 1:16-cv-00252-KG-KBM Document 132 Filed 07/29/16 Page 13 of 14

3. Whether Threatened Injury to Plaintiffs Outweighs the Harm the Preliminary Injunction

May Cause Defendants

Plaintiffs argue that the threatened injuries, i.e., traffic congestion, safety issues, and loss of

business, outweigh the inconvenience of complying with NEPA procedures, including an EA or

possible EIS. Plaintiffs cite the Ninth Circuit: The balance of equities and the public interest

favor issuance of an injunction because allowing a potentially environmentally damaging

program to proceed without an adequate record of decision runs contrary to the mandate of

NEPA. Sierra Club v. Bosworth, 510 F.3d 1016, 1033 (9th Cir. 2007). Plaintiffs harms,

understandably, reflect personal preferences, but also do not meet the legal test. See Amoco

Prod. Co. v. Vill. of Gambell, AK, 480 U.S. 531, 545 (1987) (where injury to environment not at

all probable and large expenditure of money on project, economic investment outweighs

environmental harm). Furthermore, not allowing ART to go forward will keep the City from

building a project to revitalize the area and address pedestrian safety and improve transit

efficiency. Also, the evidence sufficiently indicates that delaying ART will lead to increased

construction costs because the City will have to pay its contractors to keep them mobilized

during cold weather and for any period of delay caused by an injunction. (Doc. 72) at 50.

Riordan testified that costs could amount to $7,500 per day should work stop. Moreover, the

Citys current construction schedule is such that it will minimize impacts to businesses and

residents, especially during peak shopping times during Christmas, Summerfest, Balloon Fiesta,

and State Fair. Plaintiffs have not persuaded me that this third preliminary injunction

requirement favors a preliminary injunction.

4. Whether an Injunction Would be Adverse to the Public Interest

Because building ART will have devastating consequences on Centrals economy, area

travel patterns, and historical resources, Plaintiffs argue that the public interest favors an

13

Case 1:16-cv-00252-KG-KBM Document 132 Filed 07/29/16 Page 14 of 14

injunction. (Doc. 50) at 53. The City argues that the public interest requires denying an

injunction. I agree. Completing the ART project on time will address existing safety concerns

sooner and save the public money due to construction delays. Also, I note that an injunction

will, in part, serve Plaintiffs private interests, i.e., their business and financial interests, rather

than the publics interest at large. Finally, I acknowledge that at least a majority of the City

Council, the Mayor, and other elected officials have investigated the ART project and have

determined that it is in the publics interest. A preliminary injunction, on the whole, would be

adverse to the public interest.

IT IS ORDERED that Plaintiffs Coalition to Make ART Smart, et als Motion for a

Preliminary Injunction and Bautista Plaintiffs Motion for Preliminary Injunction (Docs. 45 and

48) are denied.

_______________________________

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE

14

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Motion To Fix BailDocumento5 pagineMotion To Fix BailCompos Mentis100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- FBI Teams Hit Bandidos Across NM With Search WarrantsDocumento173 pagineFBI Teams Hit Bandidos Across NM With Search WarrantsAlbuquerque Journal100% (3)

- Ruling - Findings of Facts and Conclusions of Law in Redistricting CaseDocumento14 pagineRuling - Findings of Facts and Conclusions of Law in Redistricting CaseAlbuquerque JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- Mountainair RD Capilla PILE RX Map 2023Documento1 paginaMountainair RD Capilla PILE RX Map 2023Albuquerque JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- PED - Public School Support Request FY25Documento3 paginePED - Public School Support Request FY25Albuquerque Journal0% (1)

- Passive Rainwater Harvesting GuideDocumento32 paginePassive Rainwater Harvesting GuideAlbuquerque JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- NRAKozuch Letter 1Documento1 paginaNRAKozuch Letter 1Albuquerque JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- NRA2023 09 14 2023petitionDocumento34 pagineNRA2023 09 14 2023petitionAlbuquerque JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- What To Do If Someone Goes MissingDocumento1 paginaWhat To Do If Someone Goes MissingAlbuquerque JournalNessuna valutazione finora

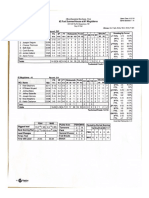

- Sandia VV 5 A Boys FinalDocumento1 paginaSandia VV 5 A Boys FinalAlbuquerque JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- Gallup KC 4 A Girls FinalDocumento1 paginaGallup KC 4 A Girls FinalAlbuquerque JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- Executive Order 2023-130Documento3 pagineExecutive Order 2023-130Albuquerque JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- NMSU Basketball Players Sue Coaches, Teammates, RegentsDocumento28 pagineNMSU Basketball Players Sue Coaches, Teammates, RegentsAlbuquerque JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- Executive Order 2023-132Documento3 pagineExecutive Order 2023-132Albuquerque JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- Joint Motion For Stip Dismissal of Appeal and RemandDocumento7 pagineJoint Motion For Stip Dismissal of Appeal and RemandAlbuquerque JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- Full Day PD OptionDocumento4 pagineFull Day PD OptionAlbuquerque JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- Magdalena Fort Sumner HouseDocumento1 paginaMagdalena Fort Sumner HouseAlbuquerque JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- Hope AAClass 4 ABoys FinalDocumento1 paginaHope AAClass 4 ABoys FinalAlbuquerque JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- Roy Mosquero To'hajiileeDocumento1 paginaRoy Mosquero To'hajiileeAlbuquerque JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- Hobbs Volcano Vista Girls 5 A FinalDocumento1 paginaHobbs Volcano Vista Girls 5 A FinalAlbuquerque JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- Robertson Navajo PrepDocumento1 paginaRobertson Navajo PrepAlbuquerque JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- Pecos ATCDocumento1 paginaPecos ATCAlbuquerque JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- ST Mikes Robertson 3 A Boys FinalDocumento1 paginaST Mikes Robertson 3 A Boys FinalAlbuquerque JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- Texico Escalante Girls 2 A FinalDocumento1 paginaTexico Escalante Girls 2 A FinalAlbuquerque JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- UNM USU BoxDocumento23 pagineUNM USU BoxAlbuquerque JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- VV Organ MountainDocumento1 paginaVV Organ MountainAlbuquerque JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- Menaul PecosDocumento1 paginaMenaul PecosAlbuquerque JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- Tohatchi SFIS3 AGirls FinalDocumento1 paginaTohatchi SFIS3 AGirls FinalAlbuquerque JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- ATCTexicoDocumento1 paginaATCTexicoAlbuquerque JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- ST Mikes Sandia PrepDocumento1 paginaST Mikes Sandia PrepAlbuquerque JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- Texico LaDocumento10 pagineTexico LaAlbuquerque JournalNessuna valutazione finora

- Support Pendente Lite Week7 DIGESTDocumento21 pagineSupport Pendente Lite Week7 DIGESTjpoy61494Nessuna valutazione finora

- CIVIL PROCEDURE Answer Updated 7 26 19 11.08pmDocumento51 pagineCIVIL PROCEDURE Answer Updated 7 26 19 11.08pmJess KaNessuna valutazione finora

- Leopoldo P. Dela Rosa For Petitioner. Emiterio C. Manibog For Private Respondent. City Fiscal of Manila For Public RespondentDocumento42 pagineLeopoldo P. Dela Rosa For Petitioner. Emiterio C. Manibog For Private Respondent. City Fiscal of Manila For Public RespondentBatang Yagit KrisTininayNessuna valutazione finora

- United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: No. 656. Docket 34180Documento4 pagineUnited States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: No. 656. Docket 34180Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- 14 Five Star Bus, Co. vs. CA-G.R. No. 120496Documento6 pagine14 Five Star Bus, Co. vs. CA-G.R. No. 120496DeniseNessuna valutazione finora

- AppealDocumento13 pagineAppealkaiaceegeesNessuna valutazione finora

- Manacop Vs CADocumento3 pagineManacop Vs CAana ortizNessuna valutazione finora

- Rule 28 - Physical and Mental Examination of PersonsDocumento4 pagineRule 28 - Physical and Mental Examination of PersonsAnonymous GMUQYq8Nessuna valutazione finora

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocumento31 pagineUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- CrimPro Codal Memory Aid FinalsDocumento33 pagineCrimPro Codal Memory Aid FinalsMartin EspinosaNessuna valutazione finora

- 128) People vs. Hernandez (99 Phil. 515 (1956) )Documento62 pagine128) People vs. Hernandez (99 Phil. 515 (1956) )Carmel Grace KiwasNessuna valutazione finora

- Hontiveros vs. RTCDocumento10 pagineHontiveros vs. RTCInna LadislaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Rodriguez Vs CADocumento4 pagineRodriguez Vs CAcarinokatrina100% (2)

- Paul Winfield Memo in SupportDocumento9 paginePaul Winfield Memo in Supportthe kingfishNessuna valutazione finora

- Sales 1Documento29 pagineSales 1I.F.S. VillanuevaNessuna valutazione finora

- 2017 Rules On Administrative Cases in The Civil Service (2017 RACCS)Documento187 pagine2017 Rules On Administrative Cases in The Civil Service (2017 RACCS)Bonny CalizoNessuna valutazione finora

- Letter To Hazel (Redacted)Documento2 pagineLetter To Hazel (Redacted)AaronWorthingNessuna valutazione finora

- Conradt v. NBC Universal, Inc. - Document No. 5Documento1 paginaConradt v. NBC Universal, Inc. - Document No. 5Justia.comNessuna valutazione finora

- PopMatters Motion For Attorney FeesDocumento21 paginePopMatters Motion For Attorney FeesbrancronNessuna valutazione finora

- Corpo Full TextDocumento188 pagineCorpo Full TextnylorjayNessuna valutazione finora

- Additional Cases Obli ConDocumento18 pagineAdditional Cases Obli ConMary Louise VillegasNessuna valutazione finora

- Abaoag Vs Diretor of LandsDocumento5 pagineAbaoag Vs Diretor of Landsem_balagteyNessuna valutazione finora

- Vilas County News-Review, March 7, 2012 - SECTION ADocumento16 pagineVilas County News-Review, March 7, 2012 - SECTION ANews-ReviewNessuna valutazione finora

- People V Rolly EspejonDocumento5 paginePeople V Rolly EspejonLizzette Dela PenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Bajaj Electricals Limited Vs Metals & Allied Products and Anr. On 4 August, 1987Documento8 pagineBajaj Electricals Limited Vs Metals & Allied Products and Anr. On 4 August, 1987RajesureshNessuna valutazione finora

- A Motion To Dismiss Is An Omnibus Motion Because It Attacks A PleadingDocumento3 pagineA Motion To Dismiss Is An Omnibus Motion Because It Attacks A PleadingNonoy D VolosoNessuna valutazione finora

- ABPA v. Ford - Appellant BriefDocumento101 pagineABPA v. Ford - Appellant BriefSarah BursteinNessuna valutazione finora

- 3 Concerned Citizens v. Judge ElmaDocumento3 pagine3 Concerned Citizens v. Judge ElmaryanmeinNessuna valutazione finora

- US V ScottDocumento2 pagineUS V ScottAnonymous hS0s2moNessuna valutazione finora