Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Photius' Bibliotheca in Byzantine Literature

Caricato da

ibasic8-1Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Photius' Bibliotheca in Byzantine Literature

Caricato da

ibasic8-1Copyright:

Formati disponibili

Photius' "Bibliotheca" in Byzantine Literature

Author(s): Aubrey Diller

Source: Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Vol. 16 (1962), pp. 389-396

Published by: Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1291167

Accessed: 01/12/2008 07:25

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless

you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you

may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=doaks.

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed

page of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the

scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that

promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to Dumbarton Oaks Papers.

http://www.jstor.org

PHOTIUS' BIBLIOTHECA

IN BYZANTINE LITERATURE

AUBREYDILLER

THE

Bibliotheca of Photius is probably

the most famous work in mediaeval

Byzantine literature. At least it is unique. The

modern special dictionaries of literature are

perhaps the nearest parallel, but Photius

deals only with books, not authors or types or

schools, and he makes no attempt to be

systematic or complete. The work was a

turning point in that it directed attention to

the treasures of ancient classical literature,

which had almost been forgotten at that

time; but this was not its special purpose, for

it includes just as much Christian literature,

which had not been forgotten. Photius has

been called a literary Columbus,1 with some

exaggeration, since he only rediscovered the

old world of literature. Nevertheless the

importance of his work is immense. Its current reputation is due in large part to the

notices of books that have since been lost, but

this is incidental. Its original value lies in the

expression of the idea of wide reading with

critical intelligence.2

In this article we intend to deal, not with

the composition of Photius' work, but with

its history from the moment it left the

author's hands, presumably A.D. 855, until it

became the common property of scholarship

at the end of the fifteenth century. A large

part of this history has already been written

in Edgar Martini's Textgeschichte (I9II),

which gives a complete account of the MSS

of the Bibliotheca.3We will supplement this

1 Krumbacherin Die Kultur der Gegenwart,

I, 8 (I905),

271, cited in Hermes, 79 (I944), 44,

note.

2 F. Dvornik, "Patriarch Photius, Scholar

and Statesman,"

3-I8;

3

I4 (I960),

Classical Folia,

13 (I959),

3-22.

E. Martini, Textgeschichte der Bibliotheke

des Patriarchen Photios von Konstantinopel,

I. Teil: Die Handschriften, Ausgaben und Ubertragungen (Abhandl. der phil.-hist. Kl. der k. sdchsischen Gesellsch. der Wissensch.,

28, 6 [I9II]).

The second part, "der die unseren Handschriften vorausliegende Phase bis zum Urexemplar des Werkes zum Gegenstand haben

from excerpts and other traces in Byzantine

literature, many of which were collected by

Martini himself, Heseler,4 and others. In a

very keen investigation of certain evidence of

this kind, bearing on Proclus' Chrestomathy

(Photius' cap. 239), Albert Severyns threw a

flood of light on the early history of the

Bibliotheca.5 The new edition, begun auspiciously by Rend Henry in I959, provides, as

far as it goes, the one prerequisite for an

effective evaluation of the testimonia for the

history of the work, that is, a critical apparatus of variant readings. But unfortunately

it goes only as far as cap. 185 at present; for

the remaining two thirds we are in almost

total darkness, the old edition of Bekker being

of no use for this purpose.

Martini found that there are only two

primary MSS of the Bibliotheca. Both were

among the 482 Greek codices Cardinal Bessarion presented to the Venetian Republic in

1468, and both are now in the Biblioteca

Marciana in Venice. Codex A (Marc. gr. 450)

is the older. Martini, following Bruno Keil,

ascribed it to the second half of the tenth

century, but if I am not mistaken it is

somewhat earlier. In the thirteenth century

it was copied in codex B (see infra) and soon

after was corrected extensively by Theodore

soll," was never published. See also "Studien

zur Textgeschichte der Bibliotheke ..., I. Der

alte Pinax," '0 ?v Kova-av-rvovTrr6oXE

'EM?AV1K6S

cOIXOXoylK6S

1A0aoyos,

lTe-rrrKovTaST-lpiS,I86I-

giving a critical text of

the table of contents that precedes the text

in the MSS. Also "Zurhandschr.Uberlieferung

der Bibl. des Photios," CharisteriaAlois Rzach

1911

(I92I),

297-318,

(1930), I36-4I,

on codex Vat. gr. I930-3I,

apograph of Vat. gr. I89,

author in 19I1.

4 P. Heseler, review

an

unknown to the

of Martini in Berliner

philol. Wochenschr., 33 (I9I3), 585-98.

5 A. Severyns, Recherchessur la Chrestomathiede Proclos, Premierepartie: le codex239

de Photius, I, Atude paleographiqueet critique

(Bibl. de la Fac. de Philos. et Lettresde 1'Univ.de

Ligge, 78 [I938]).

AUBREY DILLER

390

Scutariotes of Cyzicus6 in Constantinople.7

Bessarion acquired it from the heirs of

Giovanni Aurispa in I459. Codex M (Marc.

gr. 45I) is ascribed to the twelfth century. In

the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries it was

in the monastery of the Theotokos in Thessalonica. It was sent to Ambrogio Traversari

from Chios in I435.8 Codex B (Paris. gr. 1266),

bombycine of the thirteenth century, is an

apograph of codex A. It was seen in Chalkeby

Stephan Gerlach in 1577 and was among the

125 Greek codices acquired in the East for the

Royal Library by Francois Sevin in 1728-32.

Aside from excerpts, these are the only MSS

of the Bibliotheca earlier than the I46o's,

when A and M came together in Bessarion's

library.9 Soon after that the Bibliotheca

became more widely known through recent

copies.

Codex A begins with the heading in

Kcovaravmajuscule (icoriov apXtErriTiO6rou

T-rvouTro67EcoS

Kai OiKOUpEVIKOV

-rraTpltpXov,

followed by the letter to Tarasius (fol. Ir) and

the pinax (fols. Iv-4v). The text itself has the

heading (5r): &Troypacpi Kai (ovapieTonrl

TCOvavsyvcooyVCivv fiTv P3it3PAcov,&v EiS

I Siayvcotiv 6 ilyaTrrlpevos ilpcov

KEqcpaAailcOC

&a65eqp6Tap&atos ETrlc-raTaro'Er0l 5E TaTroa

EiKOaCl EOVTCOV

E)' Evi TplaK6oCia. Codex M

probably had the same contents in the same

order, but the first leaf is missing and the MS

begins now with item 44 of the pinax. The

titles Myriobiblonand Bibliothecaare late and

spurious (see infra). The statement of the

number of books read as 279 is correct; the

number 280 found in the MSS and editions is

due to the omission of 89 and the subsequent

division of cap. 88. There are other errors of

6 Other

codices possessed by Theodore

Scutariotes are Marc. gr. 407, Paris gr. 1234,

174I, Bodl. Cromwell i9.

7 Martini

(p. I5) supposes that codex A

passed from Cyzicusto Athos after the death of

Scutariotesand the fall of Cyzicusto the Turks.

I do not think so. Scutariotes was active in

Constantinopleand probably resided there, and

and the presence of A there in the fourteenth

century seems to be required by the excerpts,

although we must reckon with codex B, which

was also in Constantinople.

8

G. Mercati in Studi e Testi, 90 (I939),

19-21,

28.

9 The oldest of the Italian MSS of the

Bibliotheca, Martini's hypothetical codex A,

was already a joint apographof A and M.

enumeration in the MSS, especially in A.

Codices AB omit capp. i85 and 279 in the

text and the pinax and put cap. 239 after 233

in the text but not in the pinax. Codex M

omits cap. 202 in the text but not in the

pinax. All three old codices have suffered

material mutilations: codex B is only a half,

containing

capp. 230-280,

but it preserves

the text of two quaternions lost at the end of

A. Both A and M have been worked over by

several later hands. Severyns found that the

primary text of M differs remarkably from

AB and is the product of arbitrary revision.

In spite of considerable acumen, the reviser

was not thorough or consistent and seldom

improved matters. The text of A is generally

superior.'0

The earliest trace of Photius' Bibliotheca

that has been found is an excerpt from

cap. 239 in a scholion on Plato's Republic

394C in codex Paris. gr. I807. This codex is to

be attributed to the ninth century and so is

contemporary with Photius. For various

reasons it has often been supposed that the

scholia in Paris. 1807 emanated directly or

indirectly from Photius himself. The hypothesis is attractive, but not demonstrable.

The text of the scholion is correct in one

reading (68lepcp) where ABM are corrupt

(Steup6acpcw).Perhaps it was taken from

Photius' autograph, while AM derive from an

early apograph.1

The next traces of the Bibliothecaare more

extensive and more interesting. They are

autograph scholia of Arethas of Caesarea

(ca. 850-935)12 found in two codices written

for him by the scribe Baanes in 912-914, viz.

Harley 5694 (Lucian) and Paris. gr. 451

(Clement, Justin, Eusebius, etc.). There are

large excerpts from capp. 239 and 279 and

slight traces of capp. 244 and 250. Cap. 209

also was used by Arethas in scholia on Dion

10A.

Severyns, "Les vies paralleles de

Plutarque dans la Bibliotheque de Photius,"

Melanges

Desrousseaux

(I937),

435-50,

found

the same general difference between AB and M

in cap. 245 also, and it seems to hold throughout

the Bibliotheca.

11 Severyns, pp. 261-77, takes great pains to

correct previous errors in the history of this

scholion. His own conslusions are still valid,

although we now know more about the early

Plato codices.

12 S. G. Kugeas, 'O

KaioapEias'ApkOasKat -rT

Epyov aOUro (1913).

PHOTIUS'

Chrysostom, but the autograph codex has not

survived. Arethas does not cite Photius by

name. In cap. 239 the excerpts agree constantly with codex M against A. (In 209 the

readings of A and M are not available; 279 is

omitted in AB.) This fact led Severyns to

identify Arethas with the corrector who

produced the peculiar text of M.13The characteristics of Arethas as known from autograph

work in his own codices seem to agree well

with the characteristics observed in the work

of the corrector. Presumably codex M was

copied from a lost codex owned and revised

by Arethas like others that are preserved.

Unfortunately the name of Arethas does not

occur in M, but in lieu of that is the agreement

of his autograph scholia with the text of M.

Next is a long excerpt from Photius'

cap. 250 (Agatharchides) in the Sylloge de

historia animalium14 of the scholar-emperor

Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (905-959),

who is well known for works of this kind.

Neither Photius nor Agatharchides is named.

There are also some excerpts from Ctesias,

but they do not seem to be from Photius'

cap. 72.15Although the readings of A and M

are not available for cap. 250, Constantine's

text seems to be independent of Arethas'

revision in codex M.

There are other anonymous excerpts from

Photius' cap. 250 in codex Marc. gr. 299, of

the tenth or eleventh century, the oldest

Greek alchemical codex, fols. I38r-I4ov'16

collated the three MSS in Venice sufficiently

to ascertain that the text is independent of M

and probably of A also.17

13

Severyns, pp. 279-95,

339-57,

364-74,

esp. 343f. That Arethas,as a discipleof Photius,

acquired a copy of the Bibliotheca at an early

age seems to me to be a mere assumption. All we

know is that he had it after 9I4.

14 Sp. P. Lambros ed., Excerptorum Constantini de natura animalium libri duo (Supplementum Aristotelicum, ed. Acad. litt. reg.

Boruss. I, I [I885]), pp. 44-52,

cap. 250 (45obI2-454a32).

15 Lambros, p. XIV.

from Photius

p. I4, from Photius

cap. 250

(447b6-449aIo and 457b36-458bi). The excerpts occur in some other MSS also, probably

apographs of Marc. 299, e.g. Marc. 598 (ibid.,

P. 32).

For example 447b29 yvio1icov A, xpvaicov

Marc. 299.

M, XpvuopvXicov

17

A long notice of the acts of Nicaea against

Arius, which occurs in several MSS of the

tenth century and later, has been shown by

Heseler to be copied from Photius' cap. 256

with some retouching to conceal its source and

character.18Heseler adds that capp. 257 and

258 also occur separately in some early

menologia.19In all three cases, he says, "hat

zweifellos das Bestreben, an die Stelle der

grossen vormetaphrastischen Viten kiirzere

Texte zu setzen, mitgewirkt." The relation

of these large excerpts to codices A and M of

the Bibliothecaremains to be determined.

Several old MSS of the works of Athanasius

of Alexandria, the oldest attributed to the

eleventh century, have a notice excerpted

partly, but not quite wholly, from Photius'

capp. I39-I40. The heading has been understood to say that the excerpt is from a lost

letter of Photius to his brother Tarasius,20but

I think it is rather a citation of the untitled

Bibliotheca itself with its initial letter to

Tarasius. The extra information can have been

added by the excerptor on his own. This is the

only citation of Photius by name that we have

before the thirteenth century.

The so-called Etymologicum Magnum has

an article on AEsyoS

entitled EKTOJ TrEpi

XPparopiaOias

TTp6Koou,which is excerpted from

Photius' cap. 239, and P. Becker21found four

other tiny bits excerpted from 239 and three

from 279 (532b27-8) widely distributed in the

Etymologicum.Severyns shows that in cap. 239

they agree with A against M even in errors.

Cap. 279, however, is lacking in A, and it may

be doubted that it was the source for these

excerpts. This Etymologicumis attributed to

18 P. Heseler, "Die Vita

(Metrophaniset

Alexandri)des Photius und die Acta in Nicaea

(BHG2 I280)," Byz.-neugr. Jahrbiicher, 13 (I937),

81-92.

19 Bibliotheca

hagiographica

graeca I472 and

I84; A. Ehrhard, Uberlieferung und Bestand der

hagiographischen und homiletischen Literatur der

griechischen Kirche, I, I (Texte und Untersuchungen,

16J. Bidez et al., Catalogue des Mss. alchim.

grecs, 2 (I927),

391

BIBLIOTHECA

50 [I937]),

483f.,

497,

625. These

excerpts, too, do not mention Photius; on this

point Mr. Nigel G. Wilson, of the Bodleian

Library, kindly inspected codex Barocci 240

fol. 9v for me.

20 H. G. Opitz, Untersuchungen zur

berlieferung der Schriften des Athanasius (I935),

212-4.

21

P. Becker, De Photio et Aretha lexicorum

scriptoribus (Diss. I909)

62-5.

392

AUBREY DILLER

the early twelfth century. Our excerpts

appear to be interpolations in the original

text, but very early ones, as they are in all

the MSS.22

Two other scholars of the twelfth century,

Michael Italicus and Eustathius, have each a

single passage in which they draw on Photius'

cap. 239. Severyns (pp. 319-36) examines

them carefully and concludes that both

depend on the revised text of codex M, itself

of the twelfth century. If that is so, these

excerpts have no connection with those in the

Etymologicum.

These are all the traces of Photius'

Bibliotheca in the middle Byzantine period

(fromthe ninth to the twelfth century) I know

of. They show that the work was well known

from an early time. In fact some of them may

be due to Photius himself. Two copies of the

Bibliotheca survive from this period, exhibiting a pure and an impure text respectively. However, some of the traces at least are

independent of both texts and seem to attest

the existence of a third. We hope the situation

will become clearer when the critical apparatus for the latter part of the Bibliotheca

is available.

In the late Byzantine period (after the

recovery of the metropolis in 1261) the

situation is changed. The traces of the Bibliotheca are more frequent, but at least most of

them derive from one or the other of the two

old copies. Codex M was in Thessalonica.

Unfortunately the location of codex A is not

attested, but I think it was in Constantinople.

Codex B was copied from A at the beginning

of this period and probably remained in Constantinople too. In the fifteenth century both

A and M made their way to Italy and finally,

by 1468, into the possession of Bessarion.

Given this location of the sources the proliferation of traces in the fourteenth century

should be more from AB than from M,

followed by an outburst in Italy towards the

end of the fifteenth century.

We may begin our survey of the late

Byzantine traces with the most interesting

22

Severyns, pp. 297-318, deals at length with

previouserrorsregardingthese excerpts. Becker

and Severynsthink the excerptorfoundcap. 239

(and 279) in a separate pamphlet, but I think the

TOuin the title can refer just as well to the

chapter in the Bibliotheca.

of all. These are excerpts in various codices,

but all with the same heading (or nearly so)

and probably all in the same handwriting.

The heading supplies an old lack in the Bibliotheca, presenting us for the first time with a

title for the nameless work, and that a bold

one. It reads: -TOUayltCoTrou (DCOTiOU?KTTjS

XEyoogvrS lupiopirrpay/atias auOou -rTTS

The participle suggests

pAou KEapXatov...

that the author found this title already current, but the emphasis and the repetition

suggests that it is of his own coinage. It is

still used as an alternate.

Under this heading in codex Paris. suppl.

gr. 256, fols. 239-47, which are a separate MS

in the codex, in a different hand and ending

abruptly, we have quite a corpus of excerpts

from the Bibliotheca: capp.

212,

211, 232, 214,

251, 249, 278, 245, all more or less abridged.23

Some of the chapters have numbers, and

they agree with those of the second hand in

codex A of the Bibliotheca (thus 251 is cv').

Martini (pp. 45, io6) found that the text of

the excerpts also agrees with codex A after it

was corrected by the third hand. Codex Paris.

suppl. 256 belonged to Theodore Sophianus

(d. I456)24and later to Pierre Pantin (d. 16II)

and Andreas Schott (d. 1629), both of whom

resided in Spain in the latter part of the

sixteenth century.25

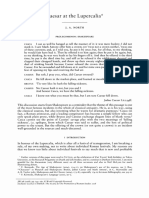

With the same heading and in the same

handwriting Photius' cap. 187 occurs as an

introduction to Nicomachus' Arithmetica in

codex Vat. gr. I98, fol. Ir (fig. i). It has the

incorrect number p-rs' given to this chapter

by the second hand in codex A because of the

omission of cap. 185 (Martini, p. 8). The age

and milieu of Vat. 198 are suggested by its

contents,26 which include citations of Nice23Capp.

214,

251 in Paris.

gr. I772

and

capp. 251, 249 in Vindob. phil. gr. 336 (Lam-

beck 80) were probably copied from Paris.

suppl. 256.

24 L. Petit et al. edd., Oeuvres complRtesde

Georges Scholarios, I (1928), 278. Theodore

Sophianus also possessed codices Vat. gr. I434,

Ambr. gr. 230, 291, and part of Monac. gr. 36I.

25

I46f.

26

II

J. E. Powell in Class. Quart., 30 (1936),

J. L. Heiberged., Claudii Ptolemaei opera,

(I907),

pp.

XXI-IV;

G. Mercati

and P.

Franchi de' Cavalieri, Codices Vaticani Graeci,

I (1923), 236-40;

I. During ed., Die Harmonie-

lehre des Klaudios Ptolemaios (GdteborgsHogskolas Arsskrift, 36, i [1930]), pp. XXXVI, LXII.

PHOTIUS'

393

BIBLIOTHECA

phorus Gregoras (fol. 88v) and Nicolaus

Cabasilas (fol. 318r) by the primary hand, and

notes referring to the year 6882 (1373-4) by

a secondary hand (fols. 468V,516v). Gregoras

and Cabasilas were active controversialists in

Constantinople in the middle of the fourteenth

century. So the codex was probably written

in the capital in the third quarter of the

century. Ingemar During attributes it to the

school of Gregoras himself, rightly rejecting

Heiberg's attribution to Mt. Athos.

With an equivalent, but not quite the

same heading, Photius' cap. 125 occurs as an

introduction to the genuine works of Justin

in codex Paris. gr. 450, dated A.D. I363.27 A

quaternion from the beginning of a similar

codex is found in codex 86 (now 60) in the

library of the Patriarchate in Alexandria

(formerly in Cairo), fols. 4-II.28 Paris. 450

is not in the same handwriting as the excerpts

in Paris. suppl. 256 and Vat. 198, but the

quaternion in Alexandria may be. In that

case it would be the head of the lost codex

from which Paris. 450 was copied.

Since the numerous other late Byzantine

traces of the Bibliothecaare mostly anonymous

and undated, I shall arrange them in the

order of the Bibliothecaitself.

Cap. 26 occurs in main part in at least two

early MSS as an introduction to epistles of

Synesius: Vat. gr. 64, dated I270, fol. 85r, and

Paris. gr. 2988, fol. 8V. The text is not from

codex M.29

Capp. 4I and 42 occur without headings in

codex Barocci 142, fols. 240v-24Ir, added by

a different hand after Theodore Lector and

followed in the same hand by a similar notice

of an unknown church history of the early

tenth century.30The Barocci codex appears to

27

J. C. Th. von Otto ed., Justini philosophi

et martyris opera, I, I (I876), pp. XXI-III. An

apographof Paris. 450 is codex Phillipps 3081

(Claromont.82, Meermann57), now on deposit

in the British Museumfrom the Fenwick Trust.

28 J.

Bidez ed., Philostorgius Kirchengeschichte (I913), p. XXXII; idem ed., Sozomenus Kirchengeschichte (I960), p. XIV; Th. D.

Moschonas, Korca&oyolT-fis1TacTpapXiKiS

3pi3pAlo-

be the collectanea of Nicephorus Callistus

Xanthopulus for his church history (ca. 1320).31

Nicephorus says he found his sources in the

great church of S. Sophia32, which suggests

that the codex of Photius he used was at least

not M. The text of the Barocci MS, however,

agrees now with A now with M, though more

substantially with A.33

From cap. 57 a list of books of Appian's

history was compiled, with some confusion,

by a second hand in codex Laur. 70-5, of the

fifteenth century, fol. 5r.34 The same hand

wrote bits from capp. 57 (I7a2I) and 64

(26a28) on fol. Ir and drew on cap. 83 for

notices of the histories of Dionysius and

Polybius on fols. 230r and 248r. There are also

large excerpts from capp. 224 and 244 in

different hands in this codex (see infra).

Photius is never cited by name. The excerpt

from cap. 57 does not share the slight errors

of codex M of the Bibliotheca.This codex is a

primary MS for Appian and other texts it

contains. It was acquired by Janus Lascaris

for Lorenzo de' Medici in Candia (Crete) in

I492.35

Cap. 70 occurs in main part on a leaf

inserted at the head of codex Vat. gr. 130 as

an introduction to Diodorus' history, in a

fourteenth-century hand (fig. 2).36 The text

agrees with codex A against M.

Cap. I60 occurs at the end of codex Matrit.

N-IOI (now 4641) as an epilogue to the works

of Choricius of Gaza, with a remarkable

31 G. Gentz and K. Aland, "Die

Quellender

Kirchengeschichte des Nicephorus," Zeitschr.

fuii die neutest. Wissensch., 42

32 Patrologia

(I949),

104-4I.

graeca, I45, p. 609C.

33 Here are the readings of Barocci 142

agreeing with A or M, according to Henry's

cavO'riM, 24 TOV

apparatus: 9a3 v?ou A, 8 ETr'

-rlv M (sed -Thvper correct.), 27 -iE1 A, 28 s. non

om. A, 35 eOpaKadvapp. M, 35 ypaCqI A, 9b4

Kac 20 om. M, 8 ovvyayayTv M.

34 Bandini, Cat. codd.

graec. bibl. Laurent., II

(I768), 659f.; Schweighauser ed., Appiani

Alexandrini quae supersunt (I785), III, I2f.;

L. Mendelssohn in Rhein. Museum, 31 (I876),

2Iof. There are several apographs of Laur. 70-5

containing this excerpt: Breslau Rehdiger 14,

O1KilS, I (Alexandria, I945), p. 68.

29 W. Fritz, "Die handschr.

Vat. gr. I42, Paris. gr. 1682, etc.

35 Rivista di

filologia classica, 2 (I874), 413,

phil.-hist. Abteil. der bayer. Akad. der Wissensch.,

422.

36

Uberlief. der

Briefe des Bischofs Synesios," Abhandl. der

23 (I905), 324, 365.

30 Edited by C. de

(I896), I6f.

G. Mercati and P. Franchi de' Cavalieri,

Codices

Boor in Byz. Zeitschr., 5

Vaticani

Graeci,

(I923),

158.

The

excerpt was copied from this MS in codex

Vat. gr. 996.

394

AUBREY

heading and incipit:

TOJ aytlcoTArou

Kai

OiKOUVpEVIKOU

TwaTptiPXoU TC)iovU 1TiToX

'TrpoSrECopylov PrlrpoTroiTrrtlvNIKOIr8Ei?oas'

oiTOS, OVTErp

XopiKIOSXacpEtIpJv

TlrrlTcaS,

letters to George of

Several

KrTX.37

EUKpIVEi

Nicomedia are found in the correspondence

of Photius, but nothing like this. It seems

necessary to agree with Iriarte that the

epistolary form of this excerpt is a literary

fraud, suggested by the epistle to Tarasius.

The text agrees once at least with A against

M. The Madrid codex, or another like it, was

used by Macarius Chrysocephalus (ca. I350)

in his fpocovia preserved in codex Marc.

gr. 452, where the epistle to George occurs on

fol. 96r preceding works of Choricius.

The beginning of cap. 167 was excerpted in

the introduction to a selection from Joannes

Stobaeus preserved in codex Bruxell. II360

fols. I-66 of the fourteenth century.38

The epigram on Apollodorus' Bibliotheca

at the end of cap. I86 was copied by a later

hand at the end of Planudes' Anthology in

codex Marc. gr. 481 fol. Ioor, with a false

VTa P3tpXiaTov itroplheading E1ST-r EVTrTKO

KOU

Kcbvcovosfrom the beginning of cap.

I86.39 (Photius has Conon and Apollodorus in

one chapter.) In line 5, I read iK86 EX'aOpcov,

an attempt to make scan the corrupt reading

of codex M EK Eusx0pcov. Perhaps this excerpt

was made after Marc.gr. 451 (M)and 481 were

brought together by Bessarion.

Cap. I92 occurs in codex Marc. gr. 504, of

the fourteenth century, at the end as an

epilogue on the works of Maximus.40

Capp. 222 and 223 occur in codex Vindob.

theol. gr. 2Io (266 Lambeck), fols. 239

(233)v-324

(317)v.

The

history

of

these

excerpts is precise. A colophon on fol. 408

(398)r says the codex was written for Isidore

metropolitan of Thessalonica, who held that

office late in the fourteenth century. The text

of the excerpts agrees with codex M of the

37 J.

Iriarte, Regiae bibliothecae Matritensis

codices

graeci

manuscripti

(I769),

394-406;

J. B. C. d'Ansse de Villoison, Anecdota graeca

(I78I), II, i6-8; R. Foerster and E. Richtsteig

edd., Choricii Gazaei opera (I929), pp. V-XII.

38 0. Hense, De Stobaei

florilegii excerptis

Bruxellensibus (I882).

39 K. Radinger in Rhein. Museum, 58

(I903),

303.

40

A.

M. Zanetti

and

A.

Bongiovanni,

Graeca D. Marci bibliotheca (I740), 268, cited by

Heseler p. 590.

DILLER

Bibliotheca,which was in Thessalonica late in

the thirteenth century (Martini, 19, 44f.,

105f.). The excerptor quotes part of the

original long heading of the Bibliotheca,

replacing lpiivwith Photius' name and title,

which he must have found on the lost first

leaf of codex M. The Vienna codex was

bought in Constantinople by Busbeck. A

similar heading is quoted by Janus Lascaris

from a MS he saw in Galata in I49I: K -TCOV

rrapa TOUTraTrpiapxouOcrioTu dvayvcocrOvTCOVKai aCvoyiaeowvrcoV.41 This MS is not

known to exist now. It seems to have been an

excerpt, and the only early excerpt that

preserves the original heading is Vindob. 21O.

Large excerpts from capp. 224 (Memnon's

history of Heraclea, 222b9-229b35) and 244

(Diodorus' histories, 377b7-379a33) occur in

codex Laur. 70-5 (see supra on cap. 57),

fols. 226V-229v and 63v-64v, written on blank

leaves by two slightly later hands of the

fifteenth century.42A citation and quotation,

reworded, from the end of the same portion

of cap. 224 (229b28-35) occurs in a letter of

Nicephorus Gregoras (ca. I335)43

Capp.229 (265a38-bI7) and 230 (275a5-33)

are quoted by Gregory Mamme patriarch of

Constantinople, 1445-145 , in his letter to the

p3i3AloEmperorof Trebizond.44He cites EKTT-rS

TravovXuAKTrou

aveoXoyiaSc45 coriou KcovHis text seems to agree

ocravTivouAroXEcos.

with AB against M. Perhaps he had codex B,

since A was probably already in Italy.

Cap. 230 (279bI2-28oa3o) is quoted by

Isaac Argyrus (fourteenth century) in an

unedited opusculum in codex Vat. gr. II02,

fol. 29v, citing Photius by name.46

Cap. 239, Proclus' Chrestomathy, occurs

separately in many MSS, the oldest being

Marc. gr. 53I, of the fifteenth century, item

41

396.

42

Centralblattfur Bibliothekswesen, i (I884),

Copies of these excerpts are in codices

Marc. gr. 523, Monac. gr. IoI, Vindob. phil. gr. 14

(Lambeck I25).

43 R. Guilland, Correspondance de Nicephore

Gregoras (I927),

163.

44 Patrologia graeca, I6o, pp. 232C-233C. The

letter was written while Gregory was patriarch

(2I6C).

45The same monstrous title occurs in another

connection in codex Athous 37I4 Dionysiu I8o,

of the thirteenth or fourteenth century.

46 G. Mercati in Studi e Testi, 56 (I93I), 231

note 2.

PHOTIUS'

479 in Bessarion's donation of 1468, fols.

253V-257v. Others are Vat. gr. 1408, Vallicell.

gr. 39, Scorial. gr. Y.I.I3. From the last, it

was edited by Andr. Schott in Tarragona in

1585. The text is that of codex M. Probably it

was copied in Marc.531 from M in Bessarion's

library, like cap. I86 in Marc. 481 (see supra).

The heading cites Proclus, but not Photius.

Severyns ignores these MSS.47

Cap. 244 occurs with cap. 224 in codex

Laur. 70-5 (see supra).

An excerpt from cap. 278 (528a40-b22)

occurs in codex Vatic. gr. 2222, fols. 317-318,

of the fourteenth century.

Cap. 279, Helladius' Chrestomathy,occurs

in main part without title in codex 0. 1.5

(I029) in Trinity College, Cambridge, of the

fourteenth

century,

fols.

53r-56V.

Since

cap. 279 is omitted in codices AB, this MS

must derive from codex M in Thessalonica,

like capp. 222 and 223 in Vind. theol. 2Io

(see supra). Since codex M is now partly

illegible toward the end, the Cambridge MS

has a primary value. It belonged to Henry

Scrimger and Patrick Young. A copy of it,

mistakenly entitled Atovvoiov 'ArrtKlcrrov,

was sent to Joannes Meursius by Patrick

Young in I62448and cited often by Meursius

in his notes on Helladius published posthumously in I687. Martini and Heimannsfeld49

overlooked this MS.

We may close the series of later traces of

Photius' Bibliotheca with another case of

extensive excerpting like that in codex Paris.

suppl. 256. In two codices under the same

heading ?K TrfS DcorloU TroOaocpco-rTTou rra-

rTpapXouKcovcrrav-rvourT6oAcos

avOoXoyias

occur larger excerpts than any we have

noticed so far. The codices are Riccardi

gr. I250 and Vat. gr. 2240. The excerpts

47The copies of cap. 239 by Andr. Darmarius

in the late sixteenth century are in a different

category, and I omit them here (see infra, note 55).

48 Fabricius, Bibl. graeca VII, p.

42; J. Lami

ed., Joan. Meursii opera omnia, XI (1763),

426B. A copy of this excerpt is in Trin. Coll.

MS 0. 5.23 (I304).

49 H.

Heimannsfeld,"ZumText des Helladius

bei Photius (cod. 279)," Rhein. Museum, 69

(19z4), 570-4.

50 Studi ital., 2 (I894),

482; 1:oerster and

Richtsteig (see supra, note 37) p. XV. The

excerpts from Photius in Paris. gr. 2957, Regin.

gr. 13I, Marc. gr. II, 13 (Henry, II, p.

note 2) appear to be copied from this MS.

I2I,

395

BIBLIOTHECA

coincide in part (both have capp. 259-268

et al.), but each has much that is lacking in

the other. They seem to derive from codex A

of the Bibliotheca.Both look like original MSS

of the excerptor. Nevertheless Riccardi 12 is

attributed to the fifteenth century, while

Vat. 2240 appears to have been written in

Venice about 1535.51

We have reached the limit set for this

article and will not pursue the traces of the

Bibliothecain the sixteenth century except to

investigate the new and final title it acquired

at that time. Conrad Gesner, in his great

bibliography entitled Bibliotheca universalis

(I545), knows Photius' work only by the

traditional heading: Photii patriarchae descriptiones et enumerationesauthorumquotquot

ipse legerat (fol. 562r). Not long after Pierre

Gilles (d. 1555), in his little book De Bosporo

Thracio, gives a hint of the new title: Temporibus Phocionis (Photii), qui hypotheses

praecipuorumscriptorumvelutindices antiquae

bibliothecae conscripsit ....52 The new title is

not quite full-fledged in Franc. Turrianus'

Prolegomena ad Constitutiones Apostolicas

(1563): Photius Constantinopolitanusin Bibliothecasua, sic enim appellat [sic] volumeningens

de libris a se lectis. In I577 Stephan Gerlach

described a codex he saw in Chalke as (co-riov

wrcTptipxou 33lpAiov3acxliKivov,

PEya&rT pipAIoOiKrl.

AEYOEvrT

He surely did not find

this title in the original MS, if it was bombycine, and if it was codex B, as Martinithought

(p. 22).

Andr.

Schott,

in his edition

of

Proclus' Chrestomathy (1585) says, Bibliothecam autem inscripsisse putant exemplo

Diodori Siculi.... Apollodoriitem Atheniensis

exemplo, cuius extat Deorum Bibliotheca.

David Hoeschel, in the editio princeps of the

whole Bibliotheca (I601), is more correct:

Opus hocmultiplicis eruditionisalioqui P1iXlAoOriKV,alioqui splendidius pUpi6tplpAov,53 ob

51 G. Mercati

in Rhein. Museum, 65 (I9IO),

3I8.

52 P.

Gillii, De Bosporo Thracio, lib. III,

cap. IX, p. 347, ed. Elzevir (I632); C. Muller,

Geographi graeci minores, II (I86I), p. 92b.

53 I surmise that Hoeschel learned the title

pupiopipAovfrom Andr. Schott, and he from

codex Paris. suppl. 256 (see supra, note 25).

The title appears in Spain as early as I568,

perhaps from the same source; see Ch. Graux,

Essai sur les origines du fonds grec de l'Escurial

(I880), 44, 426, 428.

AUBREY DILLER

396

argumenti varietateminscripserunt: nos, autorem secuti, Excerpta & Censuras librorum,

quos Photius legerit (p. 92oa). This Latin

heading appears on the title page of the

edition, preceded, however, by BIBAIOOHKH

TOY (L)TIOY. Meanwhile the title P3tp3XoeilKrl had appeared in manuscript copies of

the whole work by Joannes Sanctamaura54

and of cap. 239 (Proclus) by Andreas Darmarius,55both writing in the latter part of the

sixteenth century.

54 Vat.

gr.

II89

and

I930-3I

(see supra,

note 3).

55 Ottob.

gr. 163, Ambr. gr. 336, Taurin.

gr. 264, Monac. gr. 306, Old Royal i6.C.XIII;

also a copy of cap. I90 in Jerusalem patr. 85

(Martini, p. 47).

While the title Bibliotheca was a Latin

coinage of the sixteenth century, pupti6pl3pov

was Greek of the fourteenth. The Greeks

made good use of Photius' work, excerpting

some chapters as aids to the study of the

respective books and others for the sake of

historical information. The idea of the work,

however, did not take root among them.

There were no successors or redactions of the

Bibliotheca, such as there were, for instance,

of the Chroniclesof Theophanes and Georgius

Monachus or of the EtymologicumMagnum.

The Bibliotheca remained the only work

Byzantium produced on the history of

literature.

* Ik

'' "

'-"

./

!g

. up

o,

, ':K,,

if

r_

AJ M

<^

~., .C .: '

^

;at*+

,t#1

. ..C

^? '-Z

.....

o,

;Iqru*l~

AfS(rti

~oJ?

P^^';'.'

~'!

Ko J " A

.,,

,j-r^

-1-+'^

Vtc

4^H ea,^

r7 ,r^

^?^r&^

.. ,r, ,

,? .r..P

l:\.:AA

&- -

.' 'l

(t

~.

'.: '

!f?'

t#^.

,A, . ~

sv ,o&r

.

l'- s'rt(T

-tTJ a

0 t,

..

~.. _r

p. $

*t

jIt

pe*a

'"JIA',

t*

r,-T,--

'4

tEtvA

K-

.'

? :...:?Pw

~

-n

r,.

;' t * ;T T

--O.,

-.

,1

'

'

I&

e, ~,..~ ~.:...

LT O

1.

t %.,,:

,

_-

'~

j(;

wo

04WV,

. ....

.

.,,

~

~,,:-~.'~~.

~,,,-p.

~-',"r''r~p~--~..-,r.Lr:

'

C,

.TA^O

"

aj

.A

,KiP

ft,

b

*6wX?

Y. .f .

~.

'

ON

<. .

,.

qi

A

S

-t ;

..,''.'

CiX

io

#*, mAi.0r

..

t~*R,.,'

~,t.

'

^. c "

-o?? r s

'

T^t'% '*;" '>

OV ?P

... r f;

A

l.) *4 ^??<^

^ii;z^

<Y,.h'?

^^yY

Yox,^<eu

* J,-

.f .

j .'-,

.,)'~

0EoT OLctEt

^ r^

..

e..

i

.~.

,*. - "* f..* <<. ;,?>* r ,,

ne f

' *

.t... vd,i

,,. ::

'~3

..:..?0

4-:

'

'

* ** "

f^*e.

,"

'

.o

piC

" .':7,,<t. h 31:r

" n r *^^ 9cm t

- < :,

,j,Z-

',

,?

A-

' ., ,'

K..

n /

'

9 *

< IF;

o ;:

I

~l

..

~e~

^i~,

"7e........A-*sr

~

"; k.. 'P,

at >sS

"-r'rt^^-^

^ ^y^_oe^^.

S.r,>

"I

rc"~ .r~,~.,7r

'

<

;

A

ti

'

...~

"nblw,^

: ... .

..............

,.,%,

,?

,1%

T ...?,

r-.

..

* < T

< ^/ *'.

; \ ,p

oc^,,,yoA .,<">ottF;

'

r.^

:,.: ?v-

te

,:.,S;

. .. :

e S b;3, T,

t}5

l,

-S

AS

? i., ...

,,,,:'

s,%

' 4' .

i'

.,

', '"

,

,i ?*'' 2

'

S

i*:'

*r

ffi^^&?^

$}

:"

?.:

....

Vaticanus Gr. 198, fol. Ir

.*.

* i-.-<'

UWi

a,

??:

ar,

...'

*;,SS:-':

::

_e

ii

?7'

taY7(JrC.t^7w,J3,NSaJ Sr4 A91

..

&t

1^

VWCAI

C

4Iv&

12AS

^Z@W:Cc

^^i^r^^<

q^4?b?9CC.v

?KJe

n ? ^

<*,

6^ZeG~~0~

4 iu^^

Px' 4"

px"4@|ci"

\

ji

'uv><<T^, crC

x '

^A"r)?-ctff'W

Go

. i

,:

wb

t*

t'r

C,

't

1 4^

k'

'"":""~~

tpx

A~ ~~~ ~~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~

C/

7ifo^", t'c^C'1"

^y ^v

nm

^ AT^^I^T^^C*

C,

.'... ', ,,

:'",'.'

:,,,,''

%t&

r

,~

%~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~'t

,?%:'

rQ

>...,,:

.-v

....

-...-i'^

,,

COY ,,

..

Vaticanus Gr. 130, fol. l

..- ?

-A

t.~<

2.

.r

'v

*.

'/

,

W^' ,..

.

,<

.*

?In,(P

4

.

.

.7,

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Varro varius: The polymath of the Roman worldDa EverandVarro varius: The polymath of the Roman worldD.J. ButterfieldNessuna valutazione finora

- RUNIA DAVID VC 2016 Philo in Byzantium An Exploration PDFDocumento23 pagineRUNIA DAVID VC 2016 Philo in Byzantium An Exploration PDFivory2011100% (1)

- Macarius Magnes ApocriticusDocumento60 pagineMacarius Magnes ApocriticusChaka AdamsNessuna valutazione finora

- George Pachymeres: Georgius Pachymeres (Greek: Γεώργιος Παχυμέρης) (1242 - c. 1310), a Byzantine GreekDocumento2 pagineGeorge Pachymeres: Georgius Pachymeres (Greek: Γεώργιος Παχυμέρης) (1242 - c. 1310), a Byzantine GreekhakosiusNessuna valutazione finora

- CAMERON, Averil. Late Antiquity and Byzantium An Identity ProblemDocumento11 pagineCAMERON, Averil. Late Antiquity and Byzantium An Identity ProblemIgor Oliveira de SouzaNessuna valutazione finora

- Methodius of Olympus Fragments On The ResurrectionDocumento2 pagineMethodius of Olympus Fragments On The ResurrectionChaka AdamsNessuna valutazione finora

- Lloyd P. Gerson, PlotinusDocumento9 pagineLloyd P. Gerson, PlotinusPrendasNessuna valutazione finora

- Byzantine Philosophers of The 15 TH Century On IdentityDocumento34 pagineByzantine Philosophers of The 15 TH Century On IdentityAdam Lorde-of HostsNessuna valutazione finora

- Philo's Role As A Platonist in AlexandriaDocumento22 paginePhilo's Role As A Platonist in AlexandriaEduardo Gutiérrez GutiérrezNessuna valutazione finora

- Freeman, Ann - Theodulf of Orleans and The Libri CaroliniDocumento48 pagineFreeman, Ann - Theodulf of Orleans and The Libri CarolinihboesmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Ousterhout Byzantine - Architecture - A - Moving - Target PDFDocumento18 pagineOusterhout Byzantine - Architecture - A - Moving - Target PDFAndrei DumitrescuNessuna valutazione finora

- (Richard Sorabji (Editor) ) Philoponus and The Rejection To The Aristotelian ScienceDocumento292 pagine(Richard Sorabji (Editor) ) Philoponus and The Rejection To The Aristotelian ScienceMónica MondragónNessuna valutazione finora

- Epigraphy Liturgy Justinianic Isthmus CaraherDocumento23 pagineEpigraphy Liturgy Justinianic Isthmus Caraherbillcaraher100% (1)

- A New Archilochus PoemDocumento10 pagineA New Archilochus Poemaristarchos76Nessuna valutazione finora

- On Nativity #1 by Romanos The MelodistDocumento12 pagineOn Nativity #1 by Romanos The MelodistHerb Wetherell100% (1)

- (Patristische Texte Und Studien 32) Miroslav Marcovich - Pseudo-Iustinus. Cohortatio Ad Graecos, de Monarchia, Oratio Ad Graecos-Walter de Gruyter (1990)Documento171 pagine(Patristische Texte Und Studien 32) Miroslav Marcovich - Pseudo-Iustinus. Cohortatio Ad Graecos, de Monarchia, Oratio Ad Graecos-Walter de Gruyter (1990)Anonymous MyWSjSNessuna valutazione finora

- Hock, Simon The Shoemaker As An Ideal CynicDocumento13 pagineHock, Simon The Shoemaker As An Ideal CynicMaria SozopoulouNessuna valutazione finora

- Bibliotheca Scriptorum Graecorum Et Latinorum TeubnerianaDocumento27 pagineBibliotheca Scriptorum Graecorum Et Latinorum TeubnerianaPS1964scribdNessuna valutazione finora

- David, The Life of The Patriarch IgnatiusDocumento39 pagineDavid, The Life of The Patriarch IgnatiusManu PapadakiNessuna valutazione finora

- The Mixed Life of Platos Philebus in Psellos The Contemplation in Saint Maximus The ConfessorDocumento11 pagineThe Mixed Life of Platos Philebus in Psellos The Contemplation in Saint Maximus The ConfessorBogdan VladutNessuna valutazione finora

- The Chronicle of MarcellinusDocumento238 pagineThe Chronicle of MarcellinusSahrian100% (1)

- Classics Catalogue 2012Documento36 pagineClassics Catalogue 2012bella_williams7613Nessuna valutazione finora

- North - 2008 - Caesar at The LupercaliaDocumento21 pagineNorth - 2008 - Caesar at The LupercaliaphilodemusNessuna valutazione finora

- Edward Courtney - The Fragmentary Latin Poets (2003, Oxford University Press, USA)Documento564 pagineEdward Courtney - The Fragmentary Latin Poets (2003, Oxford University Press, USA)Sb__100% (1)

- Bibliographical Bulletin For Byzantine Philosophy 2010 2012Documento37 pagineBibliographical Bulletin For Byzantine Philosophy 2010 2012kyomarikoNessuna valutazione finora

- Christian Conversion in Late AntiquityDocumento30 pagineChristian Conversion in Late Antiquitypiskota0190% (1)

- Ferrari - The Ilioupersis in AthensDocumento33 pagineFerrari - The Ilioupersis in AthenspsammaNessuna valutazione finora

- Euripides Bacchae (Richard Seaford) (Z-Library)Documento290 pagineEuripides Bacchae (Richard Seaford) (Z-Library)matteo liberti100% (1)

- Romanos The Melodist: On Adam and Eve and The Nativity': Introduction With Annotated Translation1Documento22 pagineRomanos The Melodist: On Adam and Eve and The Nativity': Introduction With Annotated Translation1Birsan Marilena GianinaNessuna valutazione finora

- AGAPITOS, Literature - and - Education in NicaeaDocumento40 pagineAGAPITOS, Literature - and - Education in NicaeaoerwoudtNessuna valutazione finora

- Norris, Frederick W. Poemata ArcanaDocumento14 pagineNorris, Frederick W. Poemata ArcanaadykuuunNessuna valutazione finora

- Ficino's Praise of Georgios Gemistos PlethonDocumento10 pagineFicino's Praise of Georgios Gemistos PlethonaguirrefelipeNessuna valutazione finora

- S. Cooper The Platonist Christ. of M. VictorinusDocumento24 pagineS. Cooper The Platonist Christ. of M. VictorinusAnonymous OvTUPLm100% (1)

- Tim Riggs - On The Absence of The Henads in The Liber de Causis: Some Consequences For Procline SubjectivityDocumento22 pagineTim Riggs - On The Absence of The Henads in The Liber de Causis: Some Consequences For Procline SubjectivityDereck AndrewsNessuna valutazione finora

- Archilochus: First Poet After HomerDocumento115 pagineArchilochus: First Poet After Homeraldebaran10000100% (1)

- Gregory Palamas and The Making of Palamism in The Modern AgeDocumento236 pagineGregory Palamas and The Making of Palamism in The Modern AgeJeremiah CareyNessuna valutazione finora

- Finkelberg A Anaximander's Conception of The ApeironDocumento29 pagineFinkelberg A Anaximander's Conception of The ApeironValentina Murrocu100% (1)

- L215-St. Basil Letters II:59-185Documento510 pagineL215-St. Basil Letters II:59-185Freedom Against Censorship Thailand (FACT)100% (1)

- An Annotated Date-List of The Work of Maximus The ConfessorDocumento71 pagineAn Annotated Date-List of The Work of Maximus The Confessorbogdanel90100% (2)

- Sergei Mariev Byzantine Perspectives On NeoplatonismDocumento296 pagineSergei Mariev Byzantine Perspectives On NeoplatonismLeleScieri100% (5)

- The Fragmentary Latin Histories of Late Antiquity (Ad 300-620)Documento342 pagineThe Fragmentary Latin Histories of Late Antiquity (Ad 300-620)Jordan PickettNessuna valutazione finora

- Reumann - Oikonomia, Studia Patristica 3, 1961Documento10 pagineReumann - Oikonomia, Studia Patristica 3, 1961123KalimeroNessuna valutazione finora

- Theodore Metochites 1981 Greek Orthodox Theological ReviewDocumento47 pagineTheodore Metochites 1981 Greek Orthodox Theological ReviewMatt BrielNessuna valutazione finora

- CSEL 100 Prosper Aquitanus Liber Epigrammatum PDFDocumento170 pagineCSEL 100 Prosper Aquitanus Liber Epigrammatum PDFNovi Testamenti LectorNessuna valutazione finora

- Adolph Von Menzel - Historical and Literary Studies Pagan Jewish and Christian Cd6 Id471145024 Size80Documento19 pagineAdolph Von Menzel - Historical and Literary Studies Pagan Jewish and Christian Cd6 Id471145024 Size80HotSpireNessuna valutazione finora

- Edward Watts Justinian Malalas and The EndDocumento16 pagineEdward Watts Justinian Malalas and The EndnmdrdrNessuna valutazione finora

- Ancient LibrariesDocumento13 pagineAncient Librariesfsultana100% (1)

- A Comentary On Solon's PoemsDocumento246 pagineA Comentary On Solon's PoemsCarolyn SilvaNessuna valutazione finora

- Jouanna 2012 PDFDocumento417 pagineJouanna 2012 PDFfranagraz100% (1)

- THOMSON, Ian. Manuel Chrysolaras and The Early Italian Renaissance.Documento20 pagineTHOMSON, Ian. Manuel Chrysolaras and The Early Italian Renaissance.Renato MenezesNessuna valutazione finora

- Woodstock College and The Johns Hopkins UniversityDocumento56 pagineWoodstock College and The Johns Hopkins UniversityvalentinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Lössl - Augustine in Byzantium 8Documento1 paginaLössl - Augustine in Byzantium 8hickathmocNessuna valutazione finora

- MILLER Pindar in PlatoDocumento27 pagineMILLER Pindar in Platomegasthenis1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Philippides - 2016 - Venice, Genoa, and John VIIIDocumento21 paginePhilippides - 2016 - Venice, Genoa, and John VIIIKonstantinMorozovNessuna valutazione finora

- Ovid TextsDocumento2 pagineOvid TextsPatriBronchalesNessuna valutazione finora

- Ashgate Research Companion To Byzantine Hagiography - Stephanos EfthymiadisDocumento537 pagineAshgate Research Companion To Byzantine Hagiography - Stephanos EfthymiadisHristijan CvetkovskiNessuna valutazione finora

- ProtrepticusDocumento93 pagineProtrepticusalados100% (1)

- Heidel 1909 - The ἄναρμοι ὄγκοι of Heraclides and AsclepiadesDocumento17 pagineHeidel 1909 - The ἄναρμοι ὄγκοι of Heraclides and AsclepiadesVincenzodamianiNessuna valutazione finora

- Heidegger and Religion From Neoplatonism To The PosthumanDocumento84 pagineHeidegger and Religion From Neoplatonism To The PosthumanGeorge CarpenterNessuna valutazione finora

- Sami Aydin - Sergius of Reshaina - Introduction To Aristotle and His Categories, Addressed To Philotheos-BRILL (2016)Documento340 pagineSami Aydin - Sergius of Reshaina - Introduction To Aristotle and His Categories, Addressed To Philotheos-BRILL (2016)Doctrix MetaphysicaeNessuna valutazione finora

- Marmore Lavdata BrattiaDocumento28 pagineMarmore Lavdata Brattiaibasic8-1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Fanoula Papazoglou 1917-2001 A Life Dedi PDFDocumento19 pagineFanoula Papazoglou 1917-2001 A Life Dedi PDFibasic8-1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lowe 1914Documento432 pagineLowe 1914ibasic8-150% (2)

- Mapping Maritime Networks Preiser-Kapeller 2013 PDFDocumento38 pagineMapping Maritime Networks Preiser-Kapeller 2013 PDFibasic8-1Nessuna valutazione finora

- 2017 Symposium Final ProgramDocumento2 pagine2017 Symposium Final Programibasic8-1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Vedris AA6Documento20 pagineVedris AA6ibasic8-1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Late Antique Divi and Imperial Priests oDocumento23 pagineLate Antique Divi and Imperial Priests oibasic8-1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Albu-Imperial Geography and The Medieval Peutinger MapDocumento15 pagineAlbu-Imperial Geography and The Medieval Peutinger Mapibasic8-1Nessuna valutazione finora

- UrohinziDocumento2 pagineUrohinziibasic8-1Nessuna valutazione finora

- ICP DAS WISE User Manual - V1.1.1en - 52xxDocumento288 pagineICP DAS WISE User Manual - V1.1.1en - 52xxYevgeniy ShabelnikovNessuna valutazione finora

- Table 1. Encrypt/Decrypt: Decoded Hexval Decoded Hexval Decoded Hexval Decoded HexvalDocumento5 pagineTable 1. Encrypt/Decrypt: Decoded Hexval Decoded Hexval Decoded Hexval Decoded Hexvaldusko ivanNessuna valutazione finora

- Allpile ManualDocumento103 pagineAllpile ManualKang Mas WiralodraNessuna valutazione finora

- 0028 1 VBA Macros and FunctionsDocumento5 pagine0028 1 VBA Macros and FunctionsKy TaNessuna valutazione finora

- Full Issue Literature 2 2014Documento261 pagineFull Issue Literature 2 2014sahara1999_991596100% (1)

- AMEB Theory Terms and Signs - InddDocumento9 pagineAMEB Theory Terms and Signs - InddRebekah Tan100% (3)

- R FundamentalsDocumento41 pagineR FundamentalsAryan KhannaNessuna valutazione finora

- Link It 2 Word ListDocumento5 pagineLink It 2 Word ListOwesat MohammedNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction À La PragmatiqueDocumento51 pagineIntroduction À La PragmatiquesatchejoasNessuna valutazione finora

- Pattern Based Indonesian Question Answering SystemDocumento6 paginePattern Based Indonesian Question Answering SystemEri ZuliarsoNessuna valutazione finora

- Obser 1Documento4 pagineObser 1api-307396832Nessuna valutazione finora

- Climbingk 4Documento50 pagineClimbingk 4api-303486884Nessuna valutazione finora

- KMA002 - Applied Mathematics Foundation: Linear AlgebraDocumento33 pagineKMA002 - Applied Mathematics Foundation: Linear AlgebramikeyNessuna valutazione finora

- The Mystery of The LettersDocumento6 pagineThe Mystery of The Lettersroseguy7Nessuna valutazione finora

- William Shakespeare WebQuestDocumento4 pagineWilliam Shakespeare WebQuestapi-18087631Nessuna valutazione finora

- De Thi Hoc Sinh Gioi Mon Tieng Anh Lop 7 Co File Nghe Va Dap AnDocumento11 pagineDe Thi Hoc Sinh Gioi Mon Tieng Anh Lop 7 Co File Nghe Va Dap Antrinh tuNessuna valutazione finora

- Akarshan Gupta: Work Experience SkillsDocumento1 paginaAkarshan Gupta: Work Experience SkillsAkarshan GuptaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Hospitals / Residents Problem (1962 Gale, Shapley)Documento6 pagineThe Hospitals / Residents Problem (1962 Gale, Shapley)tassoshNessuna valutazione finora

- Women, Jung and The Hebrew BibleDocumento23 pagineWomen, Jung and The Hebrew BibleArnold HailNessuna valutazione finora

- PM130 PLUS Powermeter Series PM130P/PM130E/PM130EH: Installation and Operation ManualDocumento161 paginePM130 PLUS Powermeter Series PM130P/PM130E/PM130EH: Installation and Operation ManualdracuojiNessuna valutazione finora

- Report Sem 7Documento25 pagineReport Sem 7Hitesh PurohitNessuna valutazione finora

- E82EV - 8200 Vector 0.25-90kW - v3-0 - ENDocumento548 pagineE82EV - 8200 Vector 0.25-90kW - v3-0 - ENMr.K ch100% (1)

- Chapters - M.Shovel-Making Sense of Phrasal Verbs PDFDocumento95 pagineChapters - M.Shovel-Making Sense of Phrasal Verbs PDFMartinNessuna valutazione finora

- MSTE-Plane and Spherical TrigonometryDocumento5 pagineMSTE-Plane and Spherical TrigonometryKim Ryan PomarNessuna valutazione finora

- CHRISTMAS CAROLS - SINHALA - SLCiSDocumento24 pagineCHRISTMAS CAROLS - SINHALA - SLCiSiSupuwathaNessuna valutazione finora

- GDPR 2 LogsDocumento5.212 pagineGDPR 2 LogsSaloni MalhotraNessuna valutazione finora

- POLITY 1000 MCQs With Explanatory NoteDocumento427 paginePOLITY 1000 MCQs With Explanatory NotePrabjot SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- OOPSDocumento14 pagineOOPSPriyanshu JaiswalNessuna valutazione finora

- Best Practices For OPERA Client Side Setup Windows 7 FRM11G PDFDocumento20 pagineBest Practices For OPERA Client Side Setup Windows 7 FRM11G PDFSpencer SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Tutorial Problems: Bipolar Junction Transistor (Basic BJT Amplifiers)Documento23 pagineTutorial Problems: Bipolar Junction Transistor (Basic BJT Amplifiers)vineetha nagahageNessuna valutazione finora