Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

SCMS Vol 32 No 2 Emotional Stress

Caricato da

Fitrianto Dwi UtomoCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

SCMS Vol 32 No 2 Emotional Stress

Caricato da

Fitrianto Dwi UtomoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Emotional Stress as a Trigger

for Inflammatory Skin Disorders

Monica Huynh, BA,* Rishu Gupta, BS, and John Y.M. Koo, MD

Dermatologic disorders comprise 15% to 20% of complaints seen in general practice. Skin

disorders result in a negative impact to the patient not only physically but also psychologically, socially, and occupationally. The most common trigger for several inflammatory skin

disorders, including psoriasis, is emotional stress. Understanding the significance of

emotional triggers to common inflammatory dermatologic disorders is critical to the optimal

management of these conditions. This article will provide an overview of the effects of

emotional stress on skin disorders and psychotherapeutic options.

Semin Cutan Med Surg 32:68-72 2013 Frontline Medical Communications

KEYWORDS psoriasis, eczema, atopic dermatitis, acne, stress, anxiety, psychotherapy

ermatologic disorders comprise 15%-20% of complaints

seen in general practice.1 Common inflammatory skin disorders include psoriasis, acne, and eczema. Psoriasis alone affects 2%-3% of the US population. Acne affects 30%-100% of

school age children, if one were to include acne in all its severity.2-4 Dermatologic disorders negatively affect patients physically, psychologically, psychosocially, and occupationally. They

may harm the patients well-being and cause significant hardship such as an impaired capacity to socialize from stigma or

depression; or a reduction in cash flow due to missed work

and/or the cost of treatment. Moreover, the fact that skin disorders are so prevalent makes the negative impact on quality of life

a significant social issue. One of the most common triggers for

many inflammatory skin disorders is emotional stress. Understanding the significance of emotional triggers to common inflammatory dermatologic disorders is critical for optimal management of these conditions.

Prevalence of Stress as a Trigger

for Inflammatory Skin Disorders

Stress comes in a multitude of forms and may be conceptualized into 3 main categories:

*Chicago College of Osteopathic Medicine, Illinois.

Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

Department of Dermatology, University of California, San Francisco.

Disclosures: Dr Koo is a clinical researcher for Amgen, Pfizer, Janssen, Novartis, and Eli Lily. He is a consultant for Abbott, Leo, and Photomedex.

Ms Huynh and Ms Gupta have no conflicts to report.

Correspondence: Monica Huynh, BA, Chicago College of Osteopathic Medicine,515SpruceStreet,SanFrancisco,CA94118.E-mail:monicahuynh@

gmail.com

68

major stressful life events (eg, separation, death or illness of a loved one, and financial difficulties);

psychological (intrapsychic) or personality difficulties;

and

lack of social support.5

Fortune et al conducted a study in which 60% of the study

subjects reported that stress was strongly associated as a

causal factor for their psoriasis.6 In a prospective study of 801

atopic dermatitis patients, 50% to 67% of atopic dermatitis

patients reported psychological stress to be the principal aggravating factor in their disease.7 Green et al conducted a

survey of 215 medical students with acne, 67% of whom

identified stress as a trigger of their acne flare.8 Moreover,

74% of patients with acne reported that anxiety was an exacerbating factor in their disease.9 Chiu et al observed 20 subjects and found those with the greatest increase in perceived

stress also displayed the greatest exacerbation of acne severity

in a proportional and predictable manner.10 These findings

suggest that patients generally recognize stress as a major

contributing factor to their disease state. The particular type

of stress may not be critical, as stress in its entire spectrum has

been implicated as a precipitating factor for a variety of inflammatory skin conditions such as psoriasis, acne, and

atopic dermatitis.2,10,11

Significance of Stress

and Physiologic Response

Normal physiologic response to stress involves activation of

the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic adrenomedullary (SAM) axis, both of which regulate

1085-5629/13/$-see front matter 2013 Frontline Medical Communications

DOI: 10.12788/j.sder.0003

Emotional stress as a trigger

the immune system. The interaction between the axes modulates immune function. Overall health is maintained when

these systems work in harmony. During normal response to

stress, there is an elevation of stress hormones, which serve a

protective role. When the normal response to stress is impaired, the defect may have a downstream effect, which flares

inflammatory skin conditions.

One such dysfunction is reduced responsiveness of the

HPA axis and an increased reactivity of the SAM system in

atopic patients. Atopic dermatitis patients showed altered

HPA-axis response with significantly attenuated cortisol and

adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) levels when exposed

to a standardized laboratory stressor. There was also an altered SAM-system response that was exhibited by significantly elevated catecholamine levels.12,13 Similar findings

have been reported in psoriasis patients. A study of 50 psoriasis and 20 control patients demonstrated statistically significant prolongation of the sympathetic skin response latency as compared to the control group. This prolonged

response appeared to result from the dysfunction of the sympathetic nervous system.14 When patients were experimentally stressed, psoriasis patients were found to have lower

plasma cortisol levels and higher epinephrine and norepinephrine levels when compared to controls.2,12,15 In a study

of 40 psoriasis patients with 40 age-matched controls, Richards et al found that acute experimental social stressors resulted in significantly lower serum cortisol responses for psoriasis patients who classified their psoriasis as being

responsive to stress.16 In another study of 66 psoriasis patients, Evers et al found that after 1 month peak levels of daily

stressors were associated with an increase in disease severity

and were significantly associated with lower cortisol levels.17

Consistently lower cortisol levels also suggest the HPA axis

was hypoactive in stress-reactive patients or in those who

persistently experienced higher levels of daily stressors.18-20

The impaired cortisol response to stress resulted in an upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines.21 This evidencebased data complements the clinical observation that systemic glucocorticosteroids may effectively treat psoriasis and

the withdrawal of such treatment may result in severe rebound or a pustular flare. The effect of the psychological

stress described above in skin disorders is also in line with

observations made in other noncutaneous inflammatory processes, such as rheumatoid arthritis, which exhibit similar

impaired responses.22 These findings suggested daily stressors were an influential factor and low cortisol levels had a

role in the patients disease outcome. It is therefore plausible

that dysregulation of the HPA axis and the SAM system is

involved in stress-induced onset, exacerbation, and relapse of

chronic inflammatory skin disorders such as psoriasis, atopic

dermatitis, and acne.

Early stress is postulated to result in persistent sensitization of the HPA axis, which may subsequently increase the

vulnerability to stress and pave the way for HPA axis hyporesponsiveness.11,23 Burke-Kirschbaum et al demonstrated

that neonates with a disposition to atopy (at least one parent

with atopic dermatitis) and elevated cord IgE levels had sig-

69

nificantly elevated cortisol responses to the heel prick stress

(a well-known significant stressor for the newborn) compared to controls. There was a positive correlation between

the cord IgE levels to the basal cortisol levels and the degree

of elevation in the cortisol levels in response to the stressor. A

potential link between the observations of hyperactivity in

atopic-prone newborns and hyporeactivity of the HPA axis in

long-term atopic dermatitis patients exists. In explaining the

link, it has been postulated that with the onset and/or chronification of the disease the HPA axis may switch from a hyperto a hypo-reactive state. Therefore the initial impaired hyperreactivity of the HPA axis to stressors may increase the subjects vulnerability to develop a manifestation of atopy later in

life.24 To demonstrate the latter phenomenon, children aged

9 to 14 years, with at least a 5-year history of atopic dermatitis, were subjected to a public speaking stress test. The

children with atopic dermatitis demonstrated a blunted cortisol response while the age-matched controls demonstrated

the expected elevated cortisol levels in response to stress.25

The temporal factor on disease manifestation has been suggested in psoriasis as well. It has been observed that approximately one-third of psoriasis patients manifest their disease

by the age of 15 years.24 Ferrandiz et al performed an epidemiologic study in Spain and concluded that there are 2 different groups of patients with psoriasis. Early onset psoriasis

(younger than 30 years) seemed to follow an unstable course

and showed a tendency to become severe with more extensive body surface involvement and higher Psoriasis Area and

Severity Index (PASI) scores over time compared to lateonset psoriasis.26 In another study, Gupta et al found that

psoriasis patients who exhibited early onset psoriasis (before

the age of 40 years) seemed more prone to psoriasis flares

than patients with late onset psoriasis. In 2010, Simonic et al

explored whether psoriasis was related to positive and negative traumatic life events and investigated differences between early and late onset psoriasis. The findings showed that

many psoriatic patients had histories of child and adult

abuses; and in comparison to controls, these patients had

significantly higher negative experiences. Early onset patients

had significantly higher incidents of emotional abuse, alcohol/drug abuse, and other trauma compared to the control

group. Also, late onset psoriasis patients had higher levels of

traumatic events compared to the control group. Gupta et al

found that early onset psoriasis was more often triggered by

environmental factors such as an external stress, in contrast

to late onset psoriasis. He postulated that younger populations may have greater difficulty with assertion and expression of anger, which adversely affects their ability to cope

with stress.27

Additional theories about the effect of psychological stress

exist. For example, in acne, investigators believe there is an

increased release of glucocorticoids and adrenal androgens.

Both hormones are known to worsen acne and induce sebaceous hyperplasia during emotional stress.28 In addition, it

has been postulated that the stress-induced release of neuroactive substances within the epidermis can activate inflammatory processes in the skin. Research on stress is progressing and

M. Huynh, R. Gupta, and J.Y.M. Koo

70

evidence that psychological stress corresponds with a pathological physiologic response continues to grow.

Stress Evaluation

Indications for evaluation include a history of stress that acts

as a trigger to the skin disorder, psychiatric comorbidities, or

significantly decreased quality of life. An effective and simple

question to initiate this conversation would be to inquire if

the patient has experienced stress and if this worsens the

severity of their skin condition. Additional questions about

stressful life events, depression, anxiety, feelings of fatigue or

helplessness, the existence of an adequate support system, or

experience with stress management strategies, will help the

physician determine how the patient is susceptible to the

pathophysiologic effects of stress. Patients should also be

taken through the assessment to uncover underlying psychiatric disorders, such as major depression or generalized anxiety, as described by the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders (4th edition) published by the American Psychiatric

Association.29 Patients with diagnosable psychiatric disorders should be advised to see a mental health professional.

Management of

Psychologic Symptoms With

Nonpharmacologic Approaches

Psychologic symptoms may be addressed with nonpharmacologic treatments. Options include cognitive behavioral

therapy, biofeedback, guided imagery, and relaxation training. It may be worthwhile to pursue psychologic treatments

in patients whose dermatologic disease remains unresponsive to treatment and an underlying emotional cause is suspected. For example, Waxman described a woman with a

20-year history of psoriasis that went unresolved until she

received 15 weeks of treatment under hypnosis incorporating analysis and discussion; and interpretive psychotherapy

and desensitization by reciprocal inhibition. At a 10-month

follow-up, she continued to remain clear.30 In a study of 72

patients with eczema, patients with emotional or psychiatric

disturbance had improved outcomes with the addition of

psychiatric treatment devised specifically for the study patient. In comparison, those who did not have additional psychiatric treatment did not have improved outcomes.31 Stewart et al studied 18 adults with atopic dermatitis who had

been resistant to conventional topical therapies and antihistamines. The subjects were treated with the addition of psychological treatment such as relaxation and stress management. They showed statistically significant improvement of

itching and scratching, sleep disturbance, and mood.32

Children and adolescents, in particular, may benefit from

psychologic intervention. Psychologic disorders and comorbidities may impair growth during the developmental period.

In cases where psychological causes have yet to be discovered, psychological intervention may still be beneficial in

guiding behavioral development in children and demonstrat-

ing appropriate parental attitudes and educational techniques to parents.33

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) addresses dysfunctional thought patterns, which lead to actions that may harm

the skin or interfere with dermatologic therapy.34 Shenefelt et

al outlined the steps of CBT:

identify specific maladaptive patterns through the patients verbalization of thoughts and feelings or by direct observation of behavior;

determine the goals of therapy;

develop a hypothesis for underlying beliefs or triggers

that provoke maladaptive thought patterns and behavior;

test the hypothesis by altering cognition, behavior, or

environment and observe the effects; and

revise the hypothesis if desired results are not obtained.

The purpose of this method is to overcome negative

thoughts, establish positive thoughts, and reframe their perspective toward an optimistic outlook. For example, the itchscratch cycle in atopic dermatitis patients may develop from

a conditioned response associated with feelings of anxiety or

hostility. During the anxiety provoked moments that urge

them to scratch their itch, atopic dermatitis patients may

learn constructive activities to use as a substitute for their

scratching behavior (ie, sports, music, or artwork). In a casecontrolled study of 40 CBT patients compared with 53 controls who received standard treatment alone, Fortune et al

demonstrated that a 6-week course of adjunctive CBT improved both the psoriatic lesions and psychopathology (ie,

anxiety, depression, stress).35

Biofeedback is a technique that provides feedback of the

biologic response. Patients are provided information regarding vital functions, such as heartbeat, muscle tone, skin temperature and resistance, and/or electric potential of the brain

registered by an electroencephalogram. This information is

provided as evidence of the subjects physiologic response to

their emotional state.36 Patients are then taught simple techniques, such as structured or rhythmic breathing, to modify

and control physiologic activity. Individuals learn how to

alter their autonomic response and, with enough repetition,

there may be a remodeling of behavior and an establishment

of new habits. Shenefelt regards dermatologic disorders with

an autonomic nervous system component as conditions that

can be improved by biofeedback.34 For example, biofeedback

of muscle tension via electromyography may enhance the

teaching of relaxation.34

Guided imagery is a technique that directs thoughts toward a relaxed, focused state. This is typically facilitated with

the clinician, a third-party facilitator, tapes, or scripts. The

purpose is to produce an imagination of pleasant images and

sensations resulting in a subsequent reduction of sympathetic activity and an enhancement of parasympathetic activity. Relaxation techniques (such as meditation, breathing exercises, or journal writing) may also be practical adjunctive

therapies for patients as these therapies are convenient because training and special skills are unnecessary.

Emotional stress as a trigger

Management with

Pharmacologic Approaches

When appropriate, pharmacologic agents may be beneficial

to patients. Pharmacologic therapies may be considered if

nonpharmacologic therapies were inadequate for treatment,

if the patient does not have the time to carry out a nonpharmacologic approach, or if the combination of treatment

approaches may yield better results. A collaborative effort

between clinicians managing the patient (for example, a dermatologist and a psychiatrist) may help guide treatment.

However, some patients may resist seeking management

from psychiatric care. Therefore, clinicians, such as dermatologists or general practitioners, may need to provide treatment alone. Prior to starting therapy, an initial psychiatric

evaluation may help clinicians choose the most appropriate

category of psychopharmacologic agents.

Antidepressants include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclics, monoamine oxidase inhibitor,

and buproprion. There are reports regarding positive results

with the use of SSRIs in dermatology. DErme et al found

statistically significant improvement in psycho-diagnostic

test scores in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis treated with anti-TNF agents receiving adjunct treatment with escitalopram (Lexapro) in comparison to control

groups with only anti-TNF. Although the study did not

observe a noticeable reduction in clinical severity of psoriasis,

psychological intervention led to perceived improvements in

symptom severity, quality of life, and compliance to treatment.37 In another study, Mitra et al found patients who were

receiving fluoxetine (Prozac) in addition to PUVA treatment

had enhanced response and quicker remission as compared

to the patients receiving PUVA alone.38 Moussavian reported

improvement of acne in depressed patients (2 adults and 5

adolescents) treated with paroxetine (Paxil).39 Stnder et al

evaluated the effect of paroxetine and fluvoxamine (Luvox) in

72 pruritic patients and found that the best antipruritic response with these agents was observed in patients with atopic

dermatitis, systemic lymphoma, and solid carcinoma.40 SSRIs

are also preferred because of greater tolerability and the safety

profile in comparison to other antidepressants. However, it

should be mentioned that there are also rare case reports,

which associate SSRIs with flares in psoriasis.41-43

Buproprion-SR (Welbutrin) may be effective for nondepressed individuals. Modell et al treated 10 nondepressed

atopic dermatitis patients and 10 nondepressed psoriasis patients. Six of 10 atopic dermatitis patients and 8 of 10 psoriasis patients responded to 150 mg/day for 3 weeks followed

by 300 mg/day for 3 more weeks. Baseline measures improved after 6 weeks of therapy and average body surface

area involvement was reduced by roughly 50% in both

groups. The therapeutic effect was further supported when

the 8 responders discontinued buproprion-SR and disease

severity worsened within 3 weeks.44 Gonzlez reported on an

individual in their study suffering from severe atopic dermatitis without psychiatric symptoms who was treated with buproprion and had a very good response.45

71

Some tricyclic antidepressants are effective for symptomatic relief of pruritic symptoms due to the histamine H1

blocking effect46 but caution needs to be exercised due to the

potential for a lethal overdose.

Anti-anxiety medication could be potential treatment options for short-term use during stressful situations. Alprazolam (Xanax) is a rapid-acting medication with both antidepressant and antianxiety effects. The combined effect may

be beneficial and, with a shorter and more predictable halflife, would lead to less risk and concern for systemic accumulation over time and subsequent side effects. However,

alprazolam may be sedating (depending on the dose used)

and potentially addictive.

Conclusion

Emotional stress is commonly accepted as an exacerbating

factor in the disease state of inflammatory skin disorders.

Many clinical studies continue to document its role in the

onset and exacerbation of skin disorders such as psoriasis,

eczema, and acne. Management of skin disorders may be

optimized by nonpharmacological- or pharmacological-psychological intervention.

References

1. Julian CG. Dermatology in general practice. Br J Dermatol. 1999;

141(3):518-520.

2. Heller MM, Lee ES, Koo JY. Stress as an influencing factor in psoriasis.

Skin Therapy Lett. 2011;16(5):1-4.

3. Kilkenny M, Merlin K, Plunkett A, Marks R. The prevalence of common

skin conditions in Australian school students: 3. acne vulgaris. Br J

Dermatol. 1998;139(5):840-845.

4. Barankin B, DeKoven J. Psychosocial effect of common skin diseases.

Can Fam Physician. 2002;48:712-716.

5. Gupta MA, Gupta AK, Kirkby S, et al. A psychocutaneous profile of

psoriasis patients who are stress reactors. A study of 127 patients. Gen

Hosp Psychiatry. 1989;11(3):166-173.

6. Fortune DG, Richards HL, Main CJ, Griffiths CE. What patients with

psoriasis believe about their condition. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2

Pt 1):196-201.

7. Lammintausta K, Kalimo K, Raitala R, Forsten Y. Prognosis of atopic

dermatitis. A prospective study in early adulthood. Int J Dermatol.

1991;30(8):563-568.

8. Green J, Sinclair RD. Perceptions of acne vulgaris in final year medical

student written examination answers. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42(2):

98-101.

9. Rasmussen JE, Smith SB. Patient concepts and misconceptions about

acne. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119(7):570-572.

10. Chiu A, Chon SY, Kimball AB. The response of skin disease to stress:

changes in the severity of acne vulgaris as affected by examination

stress. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(7):897-900.

11. Arndt J, Smith N, Tausk F. Stress and atopic dermatitis. Curr Allergy

Asthma Rep. 2008;8(4):312-317.

12. Buske-Kirschbaum A, Hellhammer DH. Endocrine and immune responses to stress in chronic inflammatory skin disorders. Ann N Y Acad

Sci. 2003;992:231-240.

13. Buske-Kirschbaum A, Jobst S, Wustmans A, Kirschbaum C, Rauh W,

Hellhammer D. Attenuated free cortisol response to psychosocial stress

in children with atopic dermatitis. Psychosom Med. 1997;59(4):419426.

14. Haligr BD, Cicek D, Bulut S, Berilgen MS. The investigation of autonomic functions in patients with psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51(5):

557-563.

15. Arnetz BB, Fjellner B, Eneroth P, Kallner A. Stress and psoriasis: psy-

M. Huynh, R. Gupta, and J.Y.M. Koo

72

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

choendocrine and metabolic reactions in psoriatic patients during

standardized stressor exposure. Psychosom Med. 1985;47(6):528-541.

Richards HL, Ray DW, Kirby B, et al. Response of the hypothalamicpituitary-adrenal axis to psychological stress in patients with psoriasis.

Br J Dermatol. 2005;153(6):1114-1120.

Evers AW, Verhoeven EW, Kraaimaat FW. How stress gets under the

skin: cortisol and stress reactivity in psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2010;

163(5):986-991.

Heim C, Ehlert U, Hellhammer DH. The potential role of hypocortisolism in the pathophysiology of stress-related bodily disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2000;25(1):1-35.

Fries E, Hesse J, Hellhammer J, Hellhammer DH. A new view on hypocortisolism. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30(10):1010-1016.

Miller GE, Chen E, Zhou ES. If it goes up, must it come down? Chronic

stress and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis in humans.

Psychol Bull. 2007;133(1):25-45.

Kunz-Ebrecht SR, Mohamed-Ali V, Feldman PJ, Kirschbaum C, Steptoe

A. Cortisol responses to mild psychological stress are inversely associated with proinflammatory cytokines. Brain Behav Immun. 2003;17(5):

373-383.

Chikanza IC, Grossman AS. Hypothalamic-pituitary-mediated immunomodulation: arginine vasopressin is a neuroendocrine immune mediator. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37(2):131-136.

Heim C, Newport DJ, Heit S, et al. Pituitary-adrenal and autonomic

responses to stress in women after sexual and physical abuse in childhood. JAMA. 2000;284(5):592-597.

Buske-Kirschbaum A, Fischbach S, Rauh W, Hanker J, Hellhammer D.

Increased responsiveness of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA)

axis to stress in newborns with atopic disposition. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29(6);705-711.

Buske-Kirschbaum, Jobst S, Hellhammer DH. Altered reactivity of the

hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis in patients with atopic dermatitis:

pathologic factor or symptom? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;840:747-754.

Ferrandiz C, Pujol RM, Garca-Patos, Bordas X, Smanda JA. Psoriasis of

early and late onset: a clinical and epidemiologic study from Spain. J Am

Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(6):867-873.

Gupta MA, Gupta AK, Watteel GN. Early onset ( 40 years age) psoriasis is comorbid with greater psychopathology than late onset psoriasis: a study of 137 patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 1996;76(6):464-466.

Arora MK, Yadav A, Saini Vl. Role of hormones in acne vulgaris. Clin

Biochem. 2011;44(13):1035-1040.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of

Mental Disorders. 4th ed, Text Revision. Washington, DC; 2000.

30. Waxman D. Behaviour therapy of psoriasisa hypnoanalytic and counter-conditioning technique. Postgrad Med J. 1973;49(574):591-595.

31. Brown DG, Bettley FR. Psychiatric treatment of eczema: a controlled

trial. Br Med J. 1971;2(5764):729-734.

32. Stewart AC, Thomas SE. Hypnotherapy as a treatment for atopic dermatitis in adults and children. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132(5):778-783.

33. Janowski K, Pietrzak A. Indications for psychological intervention in

patients with psoriasis. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21(5):409-411.

34. Shenefelt PD. Biofeedback, cognitive-behavioral methods, and hypnosis in dermatology: is it all in your mind? Dermatol Ther. 2003;16(2):

114-122.

35. Fortune DG, Richards HL, Griffiths CE, Main CJ. Psychological stress,

distress and disability in patients with psoriasis: consensus and variation in the contribution of illness perceptions, coping and alexithymia.

Br J Clin Psychol. 2002;41(Pt 2):157-174.

36. Sarti MG. Biofeedback in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 1998;16(6):711714.

37. DErme AM, Zanieri F, Campolmi E. Therapeutic implications of adding the psychotropic drug escitalopram in the treatment of patients

suffering from moderate-severe psoriasis and psychiatric comorbidity:

a retrospective study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012. doi: 10.1111/

j.1468-3083.2012.04690.x.

38. Mitra A, Dubey A, Mittal A. Role of anti-depressant fluoxetine in the

puva treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol.

2003;69(2):168-169.

39. Moussavian H. Improvement of acne in depressed patients treated with

paroxetine. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(5):505-506.

40. Stnder S, Bckenholt, Schrmeyer-Horst F. Treatment of chronic pruritus with the selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors paroxetine and

fluvoxamine: results of an open-labelled, two-arm proof-of-concept

study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89(1):45-51.

41. Tan Pei Lin L, Kwek SK. Onset of psoriasis during therapy with fluoxetine. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):446.e9-446.e10.

42. Hemlock C, Rosenthal JS, Winston A. Fluoxetine-induced psoriasis.

Ann Pharmacother. 1992;26(2):211-212.

43. Osborne SF, Stafford L, Orr KG. Paroxetine-associated psoriasis. Am J

Psychiatry. 2002;159(12):2113.

44. Modell JG, Boyce S, Taylor E, Katholi C. Treatment of atopic dermatitis

and psoriasis vulgaris with bupropion-SR: a pilot study. Psychosom

Med. 2002;64(5):835-840.

45. Gonzlez E, Sanguino RM, Franco MA. Bupropion in atopic dermatitis.

Pharmacopsychiatry. 2006;39(6):229.

46. Gupta MA, Guptat AK. The use of antidepressant drugs in dermatology.

J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15(6):512-518.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Psoriasis + StressDocumento8 paginePsoriasis + StressNiatazya Mumtaz SagitaNessuna valutazione finora

- Stress and Periodontal Disease PDFDocumento7 pagineStress and Periodontal Disease PDFDaniela RusnacNessuna valutazione finora

- Psychodermatological Aspects of Atopic DermatitisDocumento6 paginePsychodermatological Aspects of Atopic DermatitisEdu SajquimNessuna valutazione finora

- Orion 2013Documento5 pagineOrion 2013Elaine MedeirosNessuna valutazione finora

- Cohen 2007 Stress and DiseaseDocumento3 pagineCohen 2007 Stress and DiseaseBilly CooperNessuna valutazione finora

- Psychological Stress and Psoriasis: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocumento12 paginePsychological Stress and Psoriasis: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisFitrianidilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Acute Multiple Sclerosis RelapseDocumento16 pagineAcute Multiple Sclerosis RelapseHabib G. Moutran BarrosoNessuna valutazione finora

- Stress On ItchDocumento14 pagineStress On Itchdr putriNessuna valutazione finora

- Effects of Stress and Psychological Disorders On The Immune SystemDocumento7 pagineEffects of Stress and Psychological Disorders On The Immune SystemTravis BarkerNessuna valutazione finora

- Psychophysiological Effects of Stress Management in Patients With Atopic Dermatitis: A Randomized Controlled TrialDocumento6 paginePsychophysiological Effects of Stress Management in Patients With Atopic Dermatitis: A Randomized Controlled TrialsnrarasatiNessuna valutazione finora

- Task Resume Article - B InggrisDocumento3 pagineTask Resume Article - B Inggrisalfian khoirun nizamNessuna valutazione finora

- Art:10.1186/s12895 015 0026 XDocumento8 pagineArt:10.1186/s12895 015 0026 XjesikaNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 A 092 F 0382 Bceb 13Documento5 pagine1 A 092 F 0382 Bceb 13kamel abdiNessuna valutazione finora

- Does Stress Increase The Risk of Atopic Dermatitis in Adolescents? Results of The Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-Based Survey (KYRBWS-VI)Documento10 pagineDoes Stress Increase The Risk of Atopic Dermatitis in Adolescents? Results of The Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-Based Survey (KYRBWS-VI)Hildy IkhsanNessuna valutazione finora

- Medical Hypotheses 9: 331-335, 1982Documento5 pagineMedical Hypotheses 9: 331-335, 1982Omar DaherNessuna valutazione finora

- Psychosocial Support ofDocumento13 paginePsychosocial Support ofJEFFERSON MUÑOZNessuna valutazione finora

- Ulcera Duodenal y PsicosomtaciaDocumento4 pagineUlcera Duodenal y PsicosomtaciaLuis Fernando Segura LeivaNessuna valutazione finora

- PRD 12036Documento12 paginePRD 12036Rolando Jorge TerrazasNessuna valutazione finora

- AA Bidirectional Relationship Between Psychosocial Factors and Atopic Disorders A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocumento15 pagineAA Bidirectional Relationship Between Psychosocial Factors and Atopic Disorders A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisOlga Rib AsNessuna valutazione finora

- Depression and ObesityDocumento7 pagineDepression and Obesityetherealflames5228Nessuna valutazione finora

- Feb 6 Introd Results Disc GPSY 513 Research Paper References AbstractDocumento6 pagineFeb 6 Introd Results Disc GPSY 513 Research Paper References AbstractEva MartinNessuna valutazione finora

- Department of Dermatology Ospital NG Maynila Medical Center Pamantasan NG Lungsod NG MaynilaDocumento21 pagineDepartment of Dermatology Ospital NG Maynila Medical Center Pamantasan NG Lungsod NG MaynilaAndrean LinataNessuna valutazione finora

- Affective DisordersDocumento37 pagineAffective Disordersveronicaine91Nessuna valutazione finora

- Stressand Autoimmunity: Courtney J. Mccray,, Sandeep K. AgarwalDocumento18 pagineStressand Autoimmunity: Courtney J. Mccray,, Sandeep K. Agarwaltitis dwi tantiNessuna valutazione finora

- Depressive SintomysDocumento6 pagineDepressive SintomysBráulio LimaNessuna valutazione finora

- tmp458B TMPDocumento16 paginetmp458B TMPFrontiersNessuna valutazione finora

- Factores Psicosomaticos en PruritoDocumento10 pagineFactores Psicosomaticos en PruritoMarcos Domic SiedeNessuna valutazione finora

- In Uence of Psychological Stress On Upper Respiratory Infection-A Meta-Analysis of Prospective StudiesDocumento11 pagineIn Uence of Psychological Stress On Upper Respiratory Infection-A Meta-Analysis of Prospective StudiesThang LaNessuna valutazione finora

- Herbal Remedies For Insomnia/anxietyDocumento27 pagineHerbal Remedies For Insomnia/anxietySriram RamamurthyNessuna valutazione finora

- Stress and CopingDocumento7 pagineStress and CopingHrvoje CvitanovicNessuna valutazione finora

- Gelfand 2012Documento5 pagineGelfand 2012gyyygNessuna valutazione finora

- Pathophysiology and Psychodynamics of Disease Causation NewDocumento10 paginePathophysiology and Psychodynamics of Disease Causation NewgemergencycareNessuna valutazione finora

- Jurnal Psiko 6Documento6 pagineJurnal Psiko 6ruryNessuna valutazione finora

- Major Depressive Disorder - New Clinical, Neurobiological, and Treatment PerspectivesDocumento11 pagineMajor Depressive Disorder - New Clinical, Neurobiological, and Treatment PerspectivesArthur KummerNessuna valutazione finora

- Psoriasis and Vascular Disease: An Unsolved Mystery: ReviewDocumento6 paginePsoriasis and Vascular Disease: An Unsolved Mystery: ReviewkendinceNessuna valutazione finora

- Epidemiology: Dr. Siswanto, M.SCDocumento66 pagineEpidemiology: Dr. Siswanto, M.SCArinTa TyArlieNessuna valutazione finora

- tmp33F4 TMPDocumento7 paginetmp33F4 TMPFrontiersNessuna valutazione finora

- Medical News in The World of Atopic Dermatitis First Quarter 2016Documento5 pagineMedical News in The World of Atopic Dermatitis First Quarter 2016anon_384025255Nessuna valutazione finora

- 625Documento8 pagine625thn2u7676Nessuna valutazione finora

- Psoriasis NATURE AYFinlayDocumento48 paginePsoriasis NATURE AYFinlayMelly SyafridaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Role of Inflammation in Depression and Fatigue 2019Documento12 pagineThe Role of Inflammation in Depression and Fatigue 2019Zoltán GöndörNessuna valutazione finora

- Stress Pshycology - B InggrisDocumento4 pagineStress Pshycology - B Inggrisalfian khoirun nizamNessuna valutazione finora

- The Neurobiology of Stress and Gastrointestinal Disease: ReviewDocumento10 pagineThe Neurobiology of Stress and Gastrointestinal Disease: ReviewEstefanía Páez CoyNessuna valutazione finora

- Psycho PsoriasisDocumento61 paginePsycho PsoriasisKhiem Tran DuyNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Cope With PsoriasisDocumento7 pagineHow To Cope With PsoriasisGe NomNessuna valutazione finora

- Important NotesDocumento6 pagineImportant NotesJustabidNessuna valutazione finora

- Burnout Syndrome in Physicians-Psychological Assessment and Biomarker ResearchDocumento11 pagineBurnout Syndrome in Physicians-Psychological Assessment and Biomarker ResearchCarlos Roberto Bautista GuerreroNessuna valutazione finora

- De Ce Ne Imbolnavim (Engleza)Documento9 pagineDe Ce Ne Imbolnavim (Engleza)Ramona BunescuNessuna valutazione finora

- Thesis PsoriasisDocumento4 pagineThesis PsoriasisDereck Downing100% (2)

- 4851-Article Text-14655-2-10-20170116 PDFDocumento14 pagine4851-Article Text-14655-2-10-20170116 PDFKIMNessuna valutazione finora

- 1st LectureDocumento6 pagine1st LectureNoreen FæţįmæNessuna valutazione finora

- Skapinakis Covid 2020Documento11 pagineSkapinakis Covid 2020MicMatzNessuna valutazione finora

- Research Article Depression and Its Relationship With Coping Strategies and Illness Perceptions During The COVID-19 Lockdown in Greece: A Cross-Sectional Survey of The PopulationDocumento11 pagineResearch Article Depression and Its Relationship With Coping Strategies and Illness Perceptions During The COVID-19 Lockdown in Greece: A Cross-Sectional Survey of The PopulationNur FadillaNessuna valutazione finora

- Stress As Bodily ResponseDocumento3 pagineStress As Bodily ResponseRebekah Louise Penrice-RandalNessuna valutazione finora

- Stress and The Periodontium: Review Article 10.5005/jp-Journals-10031-1005Documento3 pagineStress and The Periodontium: Review Article 10.5005/jp-Journals-10031-1005Herpika DianaNessuna valutazione finora

- Impact of Stress On Physical and Mental Health of An IndividualDocumento7 pagineImpact of Stress On Physical and Mental Health of An IndividualNik 19Nessuna valutazione finora

- Mizokami 2004Documento9 pagineMizokami 2004jiadev85Nessuna valutazione finora

- Nstemi + Af RVRDocumento16 pagineNstemi + Af RVRFitrianto Dwi UtomoNessuna valutazione finora

- COVER ForensikDocumento1 paginaCOVER ForensikFitrianto Dwi UtomoNessuna valutazione finora

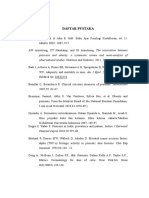

- Daftar PustakaDocumento2 pagineDaftar PustakaFitrianto Dwi UtomoNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Report: ST Elevation Miocard Infarction AnteroseptalDocumento14 pagineCase Report: ST Elevation Miocard Infarction AnteroseptalFitrianto Dwi UtomoNessuna valutazione finora

- Daftar PustakaDocumento2 pagineDaftar PustakaFitrianto Dwi UtomoNessuna valutazione finora

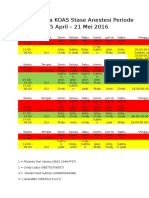

- Jadwal Jaga KOAS Stase Anestesi Periode 25 April - 21 Mei 2016Documento2 pagineJadwal Jaga KOAS Stase Anestesi Periode 25 April - 21 Mei 2016Fitrianto Dwi UtomoNessuna valutazione finora

- CC 9312Documento10 pagineCC 9312Fitrianto Dwi UtomoNessuna valutazione finora

- Daftar Pustak Dr. ArifDocumento4 pagineDaftar Pustak Dr. ArifFitrianto Dwi UtomoNessuna valutazione finora

- Psychophysiological Effects of Stress Management in Patients With Atopic Dermatitis: A Randomized Controlled TrialDocumento6 paginePsychophysiological Effects of Stress Management in Patients With Atopic Dermatitis: A Randomized Controlled TrialsnrarasatiNessuna valutazione finora

- BOOK LIST (Not Complete)Documento12 pagineBOOK LIST (Not Complete)Fitrianto Dwi UtomoNessuna valutazione finora

- Digestive Disease Stats 508 2 PDFDocumento6 pagineDigestive Disease Stats 508 2 PDFFitrianto Dwi UtomoNessuna valutazione finora

- Digestive Disease Stats 508 2 PDFDocumento6 pagineDigestive Disease Stats 508 2 PDFFitrianto Dwi UtomoNessuna valutazione finora

- Gnrs 584 Cduc Mphi Dap Presentation Schizoaffective DisorderDocumento17 pagineGnrs 584 Cduc Mphi Dap Presentation Schizoaffective Disorderapi-437250138Nessuna valutazione finora

- Objective Personality Assessment Class 8Documento87 pagineObjective Personality Assessment Class 8lpiechphdNessuna valutazione finora

- 2020 Eating DisordersDocumento13 pagine2020 Eating DisordersNathália CristimannNessuna valutazione finora

- AnxietyDocumento4 pagineAnxietyAnn DassNessuna valutazione finora

- Attention Deficit Hyperactivity DisorderDocumento10 pagineAttention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorderapi-3797941100% (1)

- Diseases Written by Harriet Bailey in 1920 and The First Psychiatric Nursing TheoristDocumento2 pagineDiseases Written by Harriet Bailey in 1920 and The First Psychiatric Nursing TheoristNaifah AbdullahNessuna valutazione finora

- GENERALIZED ANXIETY DISORDER (Script)Documento3 pagineGENERALIZED ANXIETY DISORDER (Script)Kian Justin HidalgoNessuna valutazione finora

- Hoarding DisorderDocumento22 pagineHoarding Disorderrumela.kunduNessuna valutazione finora

- Research LiteratureDocumento1 paginaResearch LiteratureThe Seafarer RamNessuna valutazione finora

- Material On Theme of Adolescent Problem - Amrutha S - 1st B.ed EnglishDocumento26 pagineMaterial On Theme of Adolescent Problem - Amrutha S - 1st B.ed EnglishAmruthaNessuna valutazione finora

- 1.3.+delusions+ +hallucinations-1Documento24 pagine1.3.+delusions+ +hallucinations-1Anonymous sSR6x6VC8aNessuna valutazione finora

- Essay - Adhd RSDDocumento12 pagineEssay - Adhd RSDapi-549234312Nessuna valutazione finora

- ScriptDocumento1 paginaScriptSherlyn Miranda GarcesNessuna valutazione finora

- Mental Status Examination - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocumento9 pagineMental Status Examination - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfGRUPO DE INTERES EN PSIQUIATRIANessuna valutazione finora

- PPPD HandoutDocumento3 paginePPPD HandoutBryanNessuna valutazione finora

- Rosewood Centers For Eating Disorders Strengthens Offerings With Co-Occurring Disorders CareDocumento3 pagineRosewood Centers For Eating Disorders Strengthens Offerings With Co-Occurring Disorders CarePR.comNessuna valutazione finora

- Hronis Et Al. (2019) Fearless Me!© - A Feasibility Case Series of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy For Adolescents With Intellectual DisabilityDocumento15 pagineHronis Et Al. (2019) Fearless Me!© - A Feasibility Case Series of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy For Adolescents With Intellectual DisabilityPhilip BeardNessuna valutazione finora

- Psychopaths 2Documento23 paginePsychopaths 2api-283565717100% (1)

- D.I.D BrochureDocumento1 paginaD.I.D Brochurehbanafsh2119Nessuna valutazione finora

- Risk For Acute Confusion 1-4Documento2 pagineRisk For Acute Confusion 1-4DewiRestiNazullyQiran100% (1)

- Psychological Analysis of Girl InterruptedDocumento2 paginePsychological Analysis of Girl InterruptedGeorge Baywong100% (1)

- QuestionDocumento8 pagineQuestionBire Rohidas SureshNessuna valutazione finora

- Handbook of Chronic Depression Diagnosis and Therapeutic Management Medical Psychiatry 25Documento470 pagineHandbook of Chronic Depression Diagnosis and Therapeutic Management Medical Psychiatry 25Milos100% (1)

- EZCare Clinic Now Offers ADD or ADHD Treatment. Diagnostic Exam For New Patients and Prescription Refills Available Today.Documento3 pagineEZCare Clinic Now Offers ADD or ADHD Treatment. Diagnostic Exam For New Patients and Prescription Refills Available Today.PR.comNessuna valutazione finora

- BorderlineDocumento12 pagineBorderlineksqvrkz4dmNessuna valutazione finora

- H-Unit 05-B.Pharmacy 4th Semester - Pharamcology.Documento3 pagineH-Unit 05-B.Pharmacy 4th Semester - Pharamcology.raviomj100% (1)

- Could It Be ADHD - ADHD Self Assessment Workbook (The Mini ADHD Coach)Documento61 pagineCould It Be ADHD - ADHD Self Assessment Workbook (The Mini ADHD Coach)andres mena100% (1)

- DSM Iv TRDocumento5 pagineDSM Iv TRTri Bunda AqshoNessuna valutazione finora

- Dyslexia and Specific Learning Disorders New International Diagnostic CriteriaDocumento6 pagineDyslexia and Specific Learning Disorders New International Diagnostic CriteriaTimothy Eduard A. SupitNessuna valutazione finora

- Child Adolescent Psychological EvaluationDocumento38 pagineChild Adolescent Psychological EvaluationdrrajivmohtaNessuna valutazione finora