Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Rethinking Religious Education and Plurality: Issues in Public Religious Education

Caricato da

patricioafCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Rethinking Religious Education and Plurality: Issues in Public Religious Education

Caricato da

patricioafCopyright:

Formati disponibili

This article was downloaded by: [University of Lethbridge]

On: 19 August 2014, At: 08:22

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House,

37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Religion & Education

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/urel20

Rethinking Religious Education and Plurality: Issues in

Public Religious Education

Robert Jackson

Published online: 11 Nov 2010.

To cite this article: Robert Jackson (2005) Rethinking Religious Education and Plurality: Issues in Public Religious Education,

Religion & Education, 32:1, 1-10, DOI: 10.1080/15507394.2005.10012346

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15507394.2005.10012346

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the Content) contained

in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no

representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the

Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and

are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and

should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for

any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever

or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of

the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic

reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any

form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://

www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Rethinking Religious Education and Plurality:

Issues in Public Religious Education

Downloaded by [University of Lethbridge] at 08:22 19 August 2014

Robert Jackson

I was delighted to be invited to speak at the American Academy of

Religion meeting in San Antonio, Texas, in November 2004, about some of

the issues raised in my recent book Rethinking Religious Education and

Plurality: Issues in Diversity and Pedagogy.1 Although I wrote the book

primarily in relation to the English educational scene, I took account of

some developments in other parts of Europe (in particular, Norway, the

Netherlands, Germany and France) and also gave some attention to recent

developments in South Africa. I am pleased that there is now the opportunity

to receive some responses and reactions to the book, especially in relation

to the debate about religion and public education in the USA.

This opening paper will give a brief rsum of the main themes in the

text. The book reflects developments in religious education in England and

Wales (Scotland and Northern Ireland have different systems), and readers

need to understand that religious education in publicly funded community

schools is fundamentally about giving pupils a knowledge and understanding

of religions, and the opportunity to reflect on their learning. The subject has

evolved over time to the extent that its current aims are very different from

those in the past. In England and Wales, at least until the late 1950s, religious

education in fully publicly funded schools2 was a form of Christian instruction

that had moral and civic as well as spiritual goals. The place of religions

within state schools in England reflects Britains particular history in becoming

a multicultural society. The aims and content of religious education (RE),

part of the statutory school curriculum since 1944, are determined by local

conferences within the constraints of successive education acts.3 Currently,

pupils in fully state funded community schools must learn about Christianity

and other principal religions represented in Great Britain in an open and

liberal manner.4 According to the new non-statutory National Framework

5

for religious education, the subject should also promote inter-cultural

understanding and social cohesion, and should thereby contribute to education

for democratic citizenship.6 Multifaith religious education in the majority,

community, schools reflects something of the plurality of society and

provides an opportunity for dialogue appropriate to a multicultural society.

Religion & Education, Vol. 32, No. 1 (Spring 2005)

Copyright 2005 by the University of Northern Iowa

Downloaded by [University of Lethbridge] at 08:22 19 August 2014

2 Religion & Education

In recent times, the complexity of the issues concerning plurality has

become increasingly evident, and recent debates about religious and values

education have taken account of this wider understanding of plurality. In his

discussion of plurality as a descriptive concept, the Norwegian scholar Geir

8

Skeie7 distinguishes between two types, traditional and modern. Skeie

also distinguishes pluralityan essentially descriptive conceptfrom the

normative concept of pluralism. Plurality, within limits, can be described

impartially, but there are different ideological stances on pluralism.

Traditional plurality corresponds to the observable cultural diversity

present in many western societies. In the case of Britain, especially since

the early 1950s, migrants moved from South Asia, East Africa and the

Caribbean, bringing significant numbers with, for example, Muslim, Hindu

and Sikh family backgrounds and minorities of other backgrounds such as

Pentecostal Christian and Rastafarian. In some countries such as South

Africa, Norway, Canada, the USA or Australia, that religious plurality also

includes the religious ways of life of indigenous peoples. These might have

been marginalized for a variety of reasons, but are once again a focus of

attention. The emergence of new religious movements and various new

age phenomena can also be seen as part of the religious and ideological

9

plurality of western societies. One also needs to take account of plurality at

local levels in societies which have appeared on the surface to be culturally

homogeneous. Research conducted by Anthony Cohen and his colleagues

shows, for example, how people from local communities can re-process

symbols, sharing some common features with the rest of the nation, but

10

overlaying them with local meaning.

Modern or postmodern plurality relates to the variegated intellectual

climate of late modernity or postmodernity. In Skeies analysis, modern

plurality points to the diversity of modern societies in the sense of being

fragmented, with various groups having competing and often contradictory

rationalities, and the growth of individualism and the privatization of religion.

Such trends are exemplified in debates about truth and meaning, knowledge

and power and personal and social identity. Critiques of assumptions, ideas

and values that characterized the European Enlightenment have led to a

plurality in contemporary thought that is often pictured as a move from

11

modernity to late modernity or high modernity or from modernity to

12

postmodernity. The very mention of these concepts opens up a huge debate,

full of terminological confusion and disagreement. I attempt a brief, general

account of the processes involved in chapter one of the book. The capacity

for instant communication across continents and the potential for access to

multiple cultural resources via the internet and other technologies are potent

symbols of modern plurality.

Downloaded by [University of Lethbridge] at 08:22 19 August 2014

Rethinking Religious Education 3

Skeies concept of modern plurality covers the terrain on which neomodernist and postmodernist positions are situated. His key point is about

the relationship between the plurality of different groups and systems and

the individual in society. The effectiveness of modern communications

ensures that individuals are exposed to a more or less constant flow of

ideas, values and ideals, each offering a different choice for action. Thus,

the competing rationalities of different groups, systems and structures

influence individuals and appear as contradictions within each person. As

Skeie remarks, We are impelled to question our identity and self13

understanding over and over again.

He makes two further points. The first is to emphasize the intertwined

relationship between traditional and modern plurality. Thus, changes and

developments within a religious tradition have to be seen not just in terms of

traditional plurality, but under influences from modern plurality. Attention to

modern plurality accentuates the inner diversity of religions and shows, for

example, the complexity of the idea of the transmission of a religion from

one generation to the next. The second (a point already made above) is to

distinguish between plurality as a descriptive concept and pluralism as a

normative one. Perhaps we can all agree that there is plurality; the stance

we take on delimiting and interpreting that plurality that is our stance on

pluralism is a matter of judgement.

This way of looking at plurality helps in the analysis of key concepts

that relate to religion in society, such as ethnicity, nationality and culture.

The debates show a range of positions from, at one extreme, closed views

that reify the concepts to postmodern views, at the other, offering complete

deconstructions. The key educational task is to engage learners, over the

years of schooling, in a critical analysis of how such ideas are used, both in

relation to their own experience and with regard to examples from a variety

of other sources. By participating in such discussions, students should also

be helped to examine their own and their peers assumptions and gradually

to formulate and clarify their own positions. Such a religious education goes

beyond simply giving information about different religions, and engages young

people at a personal level in the democratic context of the school. Different

positions within the debates (rather than their technical detail) can be used

to clarify, challenge or illuminate positions advanced by students. Obviously,

the precise content of a religious education that deals with these issues, and

the methods used, will depend on the age and aptitude of children and young

people and on other contextual factors especially the particular history of

religion and state and the related pattern of civil religion within particular

societies.

4 Religion & Education

Downloaded by [University of Lethbridge] at 08:22 19 August 2014

Responses to Plurality

In chapters two through eight of the book I discuss some different

reactions and responses to plurality, mainly in the context of the debate

about religious education in publicly funded schools in England. The most

defensive (discussed in chapter two) lies in various nostalgic attempts to

return to earlier and more secure positions, and to deny the impact of plurality

on social and personal identity. I use source material from educational debates

14

in the political sphere and from the literature on religious education to

discuss the arguments of those who wish to promote the association of

morality, religion and citizenship by nurturing a British cultural and national

identity or by arguing that Christian indoctrination is an educationally valid

approach to religious education in the common school. I argue against the

position that religious education in state-funded community schools should

be taught from a Christian perspective in order to inculcate Christian belief,

and also against the views that it is justifiable in such schools to teach

Christianity as true in order to foster a particular brand of personal and

social morality or for historical and cultural reasons. I argue that the view

that religious education should be confined to the study of Christianity is

unsustainable in the light of both social plurality locally and nationally and

the forces of globalization. With regard to the role of the Christian teacher

of religious education in the publicly funded school, I reject the view that the

only possible professional stances are Christian confessionalism on the one

hand, and procedural neutrality in which the teacher never refers to her

own personal beliefs on the other, pointing to pedagogies which have enabled

teachers to use examples from their own and their pupils experience in a

fully professional way. I conclude that arguments for traditionalist Christian

approaches to religious education in publicly funded schools are a nostalgic

attempt to insulate young people in the common school from the inevitable

influences of plurality, rather than helping pupils to engage with them, and

as over-emphasizing the influence of schools and teachers on the formation

of pupils identity.

Another response (discussed in chapter three) recognizes the reality of

plurality, but takes religion and education into private or semi-private space

in the form of schools with a particular religious character. There is no

space here to discuss the complex history of state funded religiously based

schools in England and Wales (I summarize this history in the book). Suffice

it to say that Government policy has shifted to provide active encouragement

for the extension and broadening of mainly state funded faith based

education. This has coincided with a push by the Church of England to

expand its secondary school provision within the state sector very

Downloaded by [University of Lethbridge] at 08:22 19 August 2014

Rethinking Religious Education 5

significantly, against a background of falling church attendances. Similarly,

in a climate in Britain in which the numbers engaged actively in Jewish

religious practice have been declining and an increasing number of Jews

have been marrying non-Jews, there has been a significant expansion of the

number of Jewish state funded schools. Lobbying by other minority religious

groups has also influenced Government policy, and England now has a small

number of state-funded Muslim and Sikh schools.

For children who attend such schools, particular religious values can be

allowed to permeate the whole of their education. Here, in general terms,

the aim of religious education is to nurture children into a particular religious

world view. This view is sometimes coupled with the argument that religious

education should only take place in such schools and is an anachronism in

the secular, common school. I interpret the trend towards an increase in the

provision of faith-based schools as a second type of reaction to plurality.

Although there are important arguments against such provision (and these

are aired regularly in British newspapers and other media), I take the view

that forms of faith-based education that respect the voice of the child and

maintain a stance of openness to others in society are legitimate. I argue

against forms of faith based education that isolate children from other voices

and opinions within society, and commend initiatives that link children from

different kinds of schools. I advance the view that all schools should promote

social justice (including religious tolerance), knowledge about religions, the

development of pupils skills of criticism and independent thinking as well as

dialogue and interaction between young people from different backgrounds.

A third approach (considered in chapter four) takes a radically different

view, adopting a normative postmodernist pluralism, rejecting even the study

15

of religions as the imposition of oppressive constructions. This position

rejects the introduction of textbooks and other resources about religions,

taking the view that childrens personal faith and values should be promoted

purely through the exploration of childrens personal stories. In this case,

the distinction between religious education and other forms of related

education spiritual education, education in the emotions and values

education, for example is collapsed, and the aim is to help pupils to develop

their own sets of personally constructed beliefs and values that are personally

satisfying. I argue that the fundamental problem with this approach is the

stipulation of a thoroughgoing anti-realism as its epistemological foundation.

The anti-realist ideology suffuses its pedagogy, discriminating against children

holding realist views of religious language, and depriving pupils of opportunities

to scrutinize published resources introduced by the teacher.

A fourth position (discussed in chapter five) also recognizes plurality,

but attempts to retain the integrity of different religions as discrete systems

Downloaded by [University of Lethbridge] at 08:22 19 August 2014

6 Religion & Education

of belief, distinct sources of spirituality, and as ideologies with universal

16

claims to truth. This stance seeks to promote religious literacy and to help

each pupil to identify with and argue for a particular religious or non-religious

position. The aim here is to turn out young people able to handle religious

language and claims with intelligence and informed judgement. The strength

of this version of the religious literacy approach is that it responds to plurality

in an inclusive way, seeking to help young people from all backgrounds to

clarify, criticize, formulate and justify their own positions. Its deficiency lies

principally in portraying the religions as discrete systems of belief, playing

down the diversity within religions experienced by so many pupils from

religious backgrounds.

A fifth position the interpretive approach acknowledges plurality

17

but attempts to keep the various debates associated with it open. Pupils

are encouraged to participate in those debates at their own level, through a

reflexive study of source materials in relation to personal concerns (chapter

six). The interpretive approach also aims to develop religious literacy through

helping children and young people to find their own positions within the key

debates about religious plurality. However the interpretive approach also

recognizes the inner diversity, permeable boundaries and contested nature

of religious traditions as well as the complexity of cultural expression and

change from individual and social perspectives. Having originated in

ethnographic studies of children and young people from different religious

backgrounds, the interpretive approach reflects debates within cultural or

social anthropology, emphasizing issues of representation, interpretation and

reflexivity. It utilizes pupils own beliefs and values as a resource and

encourages their active involvement in the design and evaluation of learning

activities. The process of reflexivity, for example, includes pupils reflecting

on their understanding of their own way of life through encountering

difference, criticizing constructively religious material studied at a distance,

and developing a running critique of study methods. Case studies are used

to illustrate how the approach can be adapted to meet the needs of children

in different situations and combined with elements from other pedagogies.

In the classroom situation, teaching and learning can begin according to

need at any point on the hermeneutic circle with, for example, a critical

overview of key concepts, a particular representation of a religion, case

studies of individuals or groups, or pupils experiences, concerns, questions

or interactions within the school. This approach is discussed in some detail

18

in the Fall 2004 issue of Religion and Education.

While the interpretive approach provides a pedagogy which can be

used with children who might not encounter many young people of different

faiths directly, some closely related dialogical approaches emphasise the

Downloaded by [University of Lethbridge] at 08:22 19 August 2014

Rethinking Religious Education 7

interaction of children from different religious and cultural backgrounds.

Three related dialogical approaches are introduced in chapter seven, and

are seen to utilize pupils personal knowledge and experience as sources of

19

material for study, exchange and reflection. However, in contrast to the

postmodernist personal narrative approach, these methodologies all agree

that further source material should be introduced by teachers, such as locally

based material, textual and historical sources, material relating to ethical

and human rights issues or existential questions. The relative autonomy of

individual pupils is acknowledged in these approaches, but in the context of

influences from the family and other social groups. A key element is an

emphasis on the agency of pupils in selecting and reviewing topics and

methods of study, and in being given opportunities to reflect critically both

on content and methods of study. As with the interpretive approach, much

attention is given to the development of skills and appropriate attitudes for

the study of religions and religious and values issues. Pupils are seen as colearners, joint designers of methods of study and as co-researchers with

their teachers.

In chapter eight, issues in the relationship between religious education,

multicultural (or intercultural) education, citizenship education and values

education are discussed, as is a sixth response to plurality, namely that religious

education should be removed from the curriculum of the common school,

on the grounds that society is now deeply secular. A variant on this argument

that the retention of religious education as a separate subject is unjustified

because studies of a variety of religions are irrelevant to the experience of

most pupils is also considered and rejected. The theme of the chapter is

that, while it can be argued that the study of religion is an autonomous

realm, a great deal of mutual benefit can be gained by bringing the dimension

of religious diversity and the expertise of specialists in religion to fields such

as education for democratic citizenship, intercultural education and values

education. Examples of the ways in which the study of religions is enhancing

20

international projects on intercultural education and human rights

21

education are given in chapters eight and ten.

Chapter nine adds some reflections on the relevance and contribution

of different types of theoretical and empirical research to the debates about

religious education and its practice in schools. Examples of British and

international research in religious education are considered, as are issues

such as the involvement of practitioners in RE research, training for research,

the quality of research, the provision of research funding and the dissemination

of research. The internationalization of religious education research through

the establishment of research networks within and beyond Europe is also

considered.

Downloaded by [University of Lethbridge] at 08:22 19 August 2014

8 Religion & Education

Chapter ten summarizes the argument of the book as a whole, suggesting

that the most appropriate pedagogical responses to plurality in the common

school provide a framework of democratic values which respect diversity

within the law and allow pupils to clarify and refine their own positions on

religion. In this respect, interpretive, dialogical and religious literacy

approaches are all considered to be appropriate to the situation of England

and Wales.

Epistemological, political and ethical foundations for such a pluralistic

religious education are considered, as is the broader issue of whole school

policy towards plurality, and the question as to which constituencies (teachers,

pupils, representatives of religions etc) might be involved in negotiating

syllabus content. Some primary and secondary aims for the subject are

discussed in relation to REs potential role in dealing with issues of social

cohesion. This leads to an account of the contribution of religious education

to international projects on intercultural education and education for freedom

of religion or belief. A discussion about the relationship between patterns of

civil religion in relation to education in religion, with reference to France and

England, leads to a final consideration of possible ways in which current

policy towards religious education in England and Wales might evolve.

Conclusion

Clearly, the histories of religion and state relationships and of civil religion

in different countries are key factors in shaping policy for the study of

religions in the education systems of particular states. It is no accident that

law and policy with regard to the study of religion in schools in England and

Norway have more in common with each other than with either France or

the USA. However, the arguments for developing appropriate ways of

informing young people about religious diversity based on local and global

plurality, and engaging them with the issues at a personal level, are applicable

to all democratic states. I hope that some of the issues raised in Rethinking

Religious Education and Plurality will at least help to take the debate forward

in the USA.

Notes

1. R. Jackson, Rethinking Religious Education and Plurality: Issues in

Religious Diversity and Pedagogy (London: RoutledgeFalmer, 2004).

2. Fully publicly funded schools were called county schools by the 1944

Education Act. Since 1988, they have been known as community schools.

The state also mainly funds some schools which have a religious character.

Downloaded by [University of Lethbridge] at 08:22 19 August 2014

Rethinking Religious Education 9

3. In law, the subject was called religious instruction (RI). Although the

term religious education (RE) was used widely in schools from the late

1960s, the law changing the name officially was introduced in 1988.

4. Education Reform Act 1988, Section 8.3 (Education Reform Act 1988,

London: HMSO)

5. Religious Education: The Non-statutory Framework (London:

Qualifications and Curriculum Authority, 2004).

6. Religious Education: The Non-statutory Framework (London:

Qualifications and Curriculum Authority), 2004. This document sets out to

provide information to help those with responsibility for the provision and

quality of religious education throughout the whole of the maintained system

of education.

7. The name Skeie is pronounced Shyer in English.

8. Geir Skeie, Plurality and pluralism: a challenge for religious education,

British Journal of Religious Education, 25(1) (1995): 47-59. Geir Skeie,

The concept of plurality and its meaning for religious education, British

Journal of Religious Education, 25(2) (2002): 47-59.

9. James A. Beckford, Cult Controversies: The Societal Response to the

New Religious Movements (London: Tavistock, 1985). James A. Beckford,

(ed.), New Religious Movements and Rapid Social Change (London:

Sage, 1986). P. Heelas, The New Age Movement: The Celebration of

Self and the Sacralization of Modernity (Oxford: Blackwell, 1996).

10. Anthony Cohen, (ed.), Belonging: Identity and Social Organization

in British Rural Cultures (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1982).

11. A. Giddens, The Consequences of Modernity (Cambridge: Polity Press,

1990).

12. Jean-Francois Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition: A Report on

Knowledge, trans. Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi (Manchester:

Manchester University Press, 1984).

13. Geir Skeie, Plurality and pluralism: a challenge for religious education,

British Journal of Religious Education, 25(1) (1995): 87.

14. For example, J. Burn and C. Hart, The Crisis in Religious Education

(London: Educational Research Trust, 1988).

15. C. Erricker and J. Erricker, Reconstructing Religious, Spiritual and

Moral Education (London: RoutledgeFalmer, 2000).

16. A. Wright, Religious Education in the Secondary School: Prospects

for Religious Literacy (London: David Fulton, 1993).

17. R. Jackson, Religious Education: An Interpretive Approach (London:

Hodder and Stoughton, 1997).

18. R. Jackson, Studying Religious Diversity in Public Education: An

Interpretive Approach to Religious and Intercultural Understanding, Religion

and Education 31(2) (2004): 1-20.

Downloaded by [University of Lethbridge] at 08:22 19 August 2014

10 Religion & Education

19. J. Ipgrave, Pupil to Pupil Dialogue in the Classroom as a Tool for

Religious Education, Warwick Religions and Education Research Unit

Occasional Papers II (University of Warwick, Institute of Education, 2001).

H. Leganger-Krogstad, Developing a contextual theory and practice of

religious education, Panorama: International Journal of Comparative

Religious Education and Values, 12(1) (2002): 94-104. W. Weisse,

Approaches to religious education in the multicultural city of Hamburg, in

W. Weisse (ed.) Interreligious and Intercultural Education:

Methodologies, Conceptions and Pilot Projects in South Africa,

Namibia, Great Britain, the Netherlands and Germany (Mnster:

Comenius Institut, 1996) 83-93.

20. R. Jackson, Intercultural Education and Religious Diversity: Interpretive

and Dialogical Approaches from England in Council of Europe (Ed), The

Religious Dimension of Intercultural Education (Strasbourg: Council of

Europe Publishing, 2004) pp 39-50.

21. L. Larsen and I. T. Plesner, Teaching for Tolerance and Freedom of

Religion or Belief (Oslo: The Oslo Coalition on Freedom of Religion and

Belief, University of Oslo, 2002).

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Faithful Narratives: Historians, Religion, and the Challenge of ObjectivityDa EverandFaithful Narratives: Historians, Religion, and the Challenge of ObjectivityNessuna valutazione finora

- Reconsidering Religion, Law, and Democracy: New Challenges for Society and ResearchDa EverandReconsidering Religion, Law, and Democracy: New Challenges for Society and ResearchNessuna valutazione finora

- Christianity and Education: Shaping of Christian Context in ThinkingDa EverandChristianity and Education: Shaping of Christian Context in ThinkingNessuna valutazione finora

- Social-Cultural Anthropology: Communication with the African SocietyDa EverandSocial-Cultural Anthropology: Communication with the African SocietyNessuna valutazione finora

- Science and Religion: Fifty Years After Vatican II: A Time of Peace and ReconciliationDa EverandScience and Religion: Fifty Years After Vatican II: A Time of Peace and ReconciliationNessuna valutazione finora

- What Matters?: Ethnographies of Value in a (Not So) Secular AgeDa EverandWhat Matters?: Ethnographies of Value in a (Not So) Secular AgeNessuna valutazione finora

- Learning for Life: An Imaginative Approach to Worldview Education in the Context of DiversityDa EverandLearning for Life: An Imaginative Approach to Worldview Education in the Context of DiversityNessuna valutazione finora

- Christianity and Religious Diversity: Clarifying Christian Commitments in a Globalizing AgeDa EverandChristianity and Religious Diversity: Clarifying Christian Commitments in a Globalizing AgeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1)

- Immigration and Social Cohesion in the Republic of IrelandDa EverandImmigration and Social Cohesion in the Republic of IrelandNessuna valutazione finora

- Effective Intercultural Communication (Encountering Mission): A Christian PerspectiveDa EverandEffective Intercultural Communication (Encountering Mission): A Christian PerspectiveValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (2)

- Understanding Religious Pluralism: Perspectives from Religious Studies and TheologyDa EverandUnderstanding Religious Pluralism: Perspectives from Religious Studies and TheologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Europa - Different ApproachesDocumento8 pagineEuropa - Different Approachesrichard.musondaNessuna valutazione finora

- Religious Identity and Renewal in the Twenty-first Century: Jewish, Christian and Muslim ExplorationsDa EverandReligious Identity and Renewal in the Twenty-first Century: Jewish, Christian and Muslim ExplorationsNessuna valutazione finora

- Mission and PostmodernitiesDa EverandMission and PostmodernitiesRolv OlsenNessuna valutazione finora

- College Identity Sagas: Investigating Organizational Identity Preservation and Diminishment at Lutheran Colleges and UniversitiesDa EverandCollege Identity Sagas: Investigating Organizational Identity Preservation and Diminishment at Lutheran Colleges and UniversitiesNessuna valutazione finora

- The Multicultural Leader: Developing a Catholic Personality, Second EditionDa EverandThe Multicultural Leader: Developing a Catholic Personality, Second EditionNessuna valutazione finora

- The Quiet Revolution: The Emergence of Interfaith ConsciousnessDa EverandThe Quiet Revolution: The Emergence of Interfaith ConsciousnessValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (2)

- Lonergan, Social Transformation, and Sustainable Human DevelopmentDa EverandLonergan, Social Transformation, and Sustainable Human DevelopmentNessuna valutazione finora

- Religion and American Education: Rethinking a National DilemmaDa EverandReligion and American Education: Rethinking a National DilemmaNessuna valutazione finora

- A Historical and Theoretical Guide to Studying ReligionDa EverandA Historical and Theoretical Guide to Studying ReligionNessuna valutazione finora

- (Robert Jackson) Rethinking Religious Education AnDocumento232 pagine(Robert Jackson) Rethinking Religious Education AnadybudimanNessuna valutazione finora

- Inclusive Populism: Creating Citizens in the Global AgeDa EverandInclusive Populism: Creating Citizens in the Global AgeNessuna valutazione finora

- Fundamentalism or Tradition: Christianity after SecularismDa EverandFundamentalism or Tradition: Christianity after SecularismNessuna valutazione finora

- Theology in the Public Sphere: Public Theology as a Catalyst for Open DebateDa EverandTheology in the Public Sphere: Public Theology as a Catalyst for Open DebateNessuna valutazione finora

- Globalizing Theology: Belief and Practice in an Era of World ChristianityDa EverandGlobalizing Theology: Belief and Practice in an Era of World ChristianityValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (2)

- Philosophy and Religion: From Plato to PostmodernismDa EverandPhilosophy and Religion: From Plato to PostmodernismValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- Six Degrees of Separation: A Curriculum on World ReligionDa EverandSix Degrees of Separation: A Curriculum on World ReligionNessuna valutazione finora

- Religion and Political Conflict in Latin AmericaDa EverandReligion and Political Conflict in Latin AmericaNessuna valutazione finora

- Democracy, Culture, Catholicism: Voices from Four ContinentsDa EverandDemocracy, Culture, Catholicism: Voices from Four ContinentsNessuna valutazione finora

- Hybridizing Mission: Intercultural Social Dynamics among Christian Workers on Multicultural Teams in North AfricaDa EverandHybridizing Mission: Intercultural Social Dynamics among Christian Workers on Multicultural Teams in North AfricaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Forward Movement: Evangelical Pioneers of 'Social Christianity'Da EverandThe Forward Movement: Evangelical Pioneers of 'Social Christianity'Nessuna valutazione finora

- Religious Education at Schools in Europe: Part 2: Western EuropeDa EverandReligious Education at Schools in Europe: Part 2: Western EuropeNessuna valutazione finora

- Educating People of Faith: Exploring the History of Jewish and Christian CommunitiesDa EverandEducating People of Faith: Exploring the History of Jewish and Christian CommunitiesValutazione: 3 su 5 stelle3/5 (2)

- Triple Jeopardy for the West: Aggressive Secularism, Radical Islamism and MulticulturalismDa EverandTriple Jeopardy for the West: Aggressive Secularism, Radical Islamism and MulticulturalismNessuna valutazione finora

- Multiculturalism: A Shalom Motif for the Christian CommunityDa EverandMulticulturalism: A Shalom Motif for the Christian CommunityNessuna valutazione finora

- Understanding the Sacred: Sociological Theology for Contemporary PeopleDa EverandUnderstanding the Sacred: Sociological Theology for Contemporary PeopleNessuna valutazione finora

- Divine Perspectives: Exploring the Contrasts and Convergence of Polytheism and MonotheismDa EverandDivine Perspectives: Exploring the Contrasts and Convergence of Polytheism and MonotheismNessuna valutazione finora

- Asians and the New Multiculturalism in Aotearoa New ZealandDa EverandAsians and the New Multiculturalism in Aotearoa New ZealandNessuna valutazione finora

- Interactive Pluralism in Asia: Religious Life and Public SpaceDa EverandInteractive Pluralism in Asia: Religious Life and Public SpaceNessuna valutazione finora

- Religious Education in Schools Ideas andDocumento62 pagineReligious Education in Schools Ideas andsastra damarNessuna valutazione finora

- Challenges of Postmodernity To Religious EducationDocumento12 pagineChallenges of Postmodernity To Religious EducationelmerwilsonNessuna valutazione finora

- Mission in The Context of ReligiousDocumento9 pagineMission in The Context of ReligiousJasmine SornaseeliNessuna valutazione finora

- Coping With Diversity in Religious Education An Overview HighlightedDocumento21 pagineCoping With Diversity in Religious Education An Overview Highlightedsastra damarNessuna valutazione finora

- Concerning Victims, Sexuality, and Power: A Reflection On Sexual Abuse From Latin AmericaDocumento15 pagineConcerning Victims, Sexuality, and Power: A Reflection On Sexual Abuse From Latin AmericapatricioafNessuna valutazione finora

- Revisions of Homosexuality The Catechism and "Always Our Children"Documento10 pagineRevisions of Homosexuality The Catechism and "Always Our Children"patricioafNessuna valutazione finora

- The Queer GodDocumento5 pagineThe Queer Godpatricioaf100% (1)

- Is Quarantine Related To Immediate Negative Psychological Consequences During The 2009 H1N1 Epidemic?Documento3 pagineIs Quarantine Related To Immediate Negative Psychological Consequences During The 2009 H1N1 Epidemic?patricioafNessuna valutazione finora

- Understanding, Compliance and Psychological Impact of The SARS Quarantine ExperienceDocumento11 pagineUnderstanding, Compliance and Psychological Impact of The SARS Quarantine ExperiencepatricioafNessuna valutazione finora

- Homosexual Orientation and AntDocumento12 pagineHomosexual Orientation and AntpatricioafNessuna valutazione finora

- 2017AMProgramBookSessions PDFDocumento152 pagine2017AMProgramBookSessions PDFpatricioafNessuna valutazione finora

- Theology Gay TodayDocumento19 pagineTheology Gay TodaypatricioafNessuna valutazione finora

- The Future of Liberal Theology PDFDocumento3 pagineThe Future of Liberal Theology PDFpatricioafNessuna valutazione finora

- Embodiment As Incarnation: An Incipient Queer ChristologyDocumento22 pagineEmbodiment As Incarnation: An Incipient Queer ChristologypatricioafNessuna valutazione finora

- Addressing Ethnicity Via Biblical Studie PDFDocumento214 pagineAddressing Ethnicity Via Biblical Studie PDFpatricioafNessuna valutazione finora

- Cartographies of Experience Rethinking The Method of Liberation TheologyDocumento25 pagineCartographies of Experience Rethinking The Method of Liberation TheologypatricioafNessuna valutazione finora

- Geographies of SexualitiesDocumento67 pagineGeographies of Sexualitiespatricioaf100% (1)

- Queer Theory and Historical-Critical Exe PDFDocumento6 pagineQueer Theory and Historical-Critical Exe PDFpatricioafNessuna valutazione finora

- Religion and Spirituality Across CulturesDocumento363 pagineReligion and Spirituality Across Culturespatricioaf67% (6)

- British Journal of Religious Education: An Option For South Africa inDocumento9 pagineBritish Journal of Religious Education: An Option For South Africa inpatricioafNessuna valutazione finora

- Gay Lesbian and Queer Theologies Origins Contributions and Challenges PDFDocumento13 pagineGay Lesbian and Queer Theologies Origins Contributions and Challenges PDFpatricioafNessuna valutazione finora

- At La 0001466984Documento14 pagineAt La 0001466984patricioafNessuna valutazione finora

- President Duterte SONA 2019Documento4 paginePresident Duterte SONA 2019Benaiah ValenzuelaNessuna valutazione finora

- PIL ReviewerDocumento23 paginePIL ReviewerRC BoehlerNessuna valutazione finora

- The Origins and Development of The Ottoman-Safavid ConflictDocumento214 pagineThe Origins and Development of The Ottoman-Safavid ConflictAbid HussainNessuna valutazione finora

- Uralungal Labour ContractDocumento18 pagineUralungal Labour ContractDaliya Manuel0% (1)

- Introduction To The Study of GlobalizationDocumento32 pagineIntroduction To The Study of GlobalizationHoney Kareen50% (2)

- PT3MIDYEAR2016Documento11 paginePT3MIDYEAR2016Hajariah KasranNessuna valutazione finora

- Pak Studies History NotesDocumento5 paginePak Studies History Noteshussain aliNessuna valutazione finora

- Reaction PaperDocumento2 pagineReaction Papermitsuki_sylphNessuna valutazione finora

- De Cap Tinh Lop 10Documento8 pagineDe Cap Tinh Lop 10hasuhyangg0% (1)

- Chapter 4 - 6Documento56 pagineChapter 4 - 6kankirajesh100% (1)

- Blur MagazineDocumento44 pagineBlur MagazineMatt CarlsonNessuna valutazione finora

- Race, Class & MarxismDocumento11 pagineRace, Class & MarxismCritical Reading0% (1)

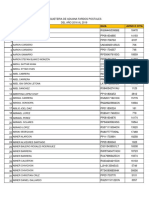

- 3 Years GENERAL POINT AVERAGE GPA PER CORE SUBJECT BY SCHOOLDocumento143 pagine3 Years GENERAL POINT AVERAGE GPA PER CORE SUBJECT BY SCHOOLRogen VigilNessuna valutazione finora

- Real-World Economics ReviewDocumento182 pagineReal-World Economics Reviewadvanced91Nessuna valutazione finora

- Course plan-LING2056Documento2 pagineCourse plan-LING2056連怡涵Nessuna valutazione finora

- Election Law CasesDocumento75 pagineElection Law CaseskkkNessuna valutazione finora

- Moef&cc Gazette 22.12.2014Documento4 pagineMoef&cc Gazette 22.12.2014NBCC IPONessuna valutazione finora

- Listado de Paqueteria de Aduana Fardos Postales PDFDocumento555 pagineListado de Paqueteria de Aduana Fardos Postales PDFyeitek100% (1)

- (B.M. No. 986.april 13, 2000) in Re 1999 Bar Examinations en Banc GentlemenDocumento1 pagina(B.M. No. 986.april 13, 2000) in Re 1999 Bar Examinations en Banc GentlemenBGodNessuna valutazione finora

- Selyem CasesDocumento20 pagineSelyem CasesMichael Cisneros100% (1)

- Edward Badgette (@acrimonyand) Nitter 9Documento1 paginaEdward Badgette (@acrimonyand) Nitter 9MichaelNessuna valutazione finora

- Islam and Human Rights: Revisiting The DebateDocumento16 pagineIslam and Human Rights: Revisiting The DebateGlobal Justice AcademyNessuna valutazione finora

- Mcod Template Paper Reslife Jameco MckenzieDocumento16 pagineMcod Template Paper Reslife Jameco Mckenzieapi-283137941Nessuna valutazione finora

- Dashnaksutyun PartyDocumento39 pagineDashnaksutyun PartyOrxan SemedovNessuna valutazione finora

- Gendered PoliticsDocumento30 pagineGendered PoliticsTherese Elle100% (1)

- Simple Citizenship InterviewDocumento2 pagineSimple Citizenship Interviewapi-250118528Nessuna valutazione finora

- DM 068, S. 2023-DbNH1KqHMdmtngf8qGznDocumento1 paginaDM 068, S. 2023-DbNH1KqHMdmtngf8qGznJAYNAROSE IBAYANNessuna valutazione finora

- USNORTHCOM FaithfulPatriotDocumento33 pagineUSNORTHCOM FaithfulPatriotnelson duringNessuna valutazione finora

- Rdo 39Documento4 pagineRdo 39Aljohn Sebuc100% (1)

- Harold Covington - The March Up CountryDocumento122 pagineHarold Covington - The March Up CountryLee McKinnisNessuna valutazione finora