Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

1 s2.0 S0148296315003409 Main

Caricato da

lucianaeuTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

1 s2.0 S0148296315003409 Main

Caricato da

lucianaeuCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Journal of Business Research 69 (2016) 314322

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Business Research

The impact of attitude functions on luxury brand consumption: An

age-based group comparison

Michael Schade a,, Sabrina Hegner b,1, Florian Horstmann a,2, Nora Brinkmann a,3

a

b

Chair of innovative Brand Management, University of Bremen, Hochschulring 4, 28359 Bremen, Germany

Faculty of Behavioural Sciences, Marketing Communication and Consumer Psychology, University of Twente, 7500 AE Enschede, the Netherlands

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 1 September 2014

Received in revised form 1 December 2014

Accepted 1 January 2015

Available online 13 August 2015

Keywords:

Luxury brands

Attitude functions

Identity development process

Purchase intention

Age

a b s t r a c t

The main purpose of this study is to understand the consumption of luxury brands in different age groups.

Attitude functions (social-adjustive, value-expressive, hedonic, utilitarian) explain luxury brand consumption

among three age groups. A total of 297 respondents between the age of 16 and 59 participated in a survey.

Using structural equation modeling, this study shows that the hedonic and utilitarian attitude functions are

relevant across all age groups, while the impact of the social functions greatly differs among the target groups.

Whereas the social-adjustive function strongly enhances luxury brand purchase behavior of late adolescents

(1625 years), value-expressiveness only impacts the luxury consumption of young adults (2639 years). The

social functions do not determine the acquisition of luxury brands by middle-aged adults (4059 years).

2015 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Young consumers are the fastest-growing segment of luxury brand

purchases. These consumers have increased their spending on luxury

goods outpacing any other demographic group (Halpert, 2012). According to a study by Roland Berger Strategy Consultants (2012), young

consumers are developing an increasingly positive attitude toward

luxury consumption. Still, more mature consumers are currently of the

greatest economic relevance in the luxury segment. According to Bain

& Co, middle-aged luxury consumers are the highest spenders (each

consumer spends an average of 1600 a year on luxury items), while

older luxury consumers make up more than 50% of luxury sales

(Roberts, 2014). To sum up, not only the established target groups of

middle-aged and older consumers but also young consumers have become a relevant target group for luxury brand managers. Consequently,

understanding the motivations of consumers' engagement in luxury

consumption in different age groups is crucial for both management

and academic research.

According to the Identity Development Process, age is an important factor that inuences personal motivations (Diehl & Hay, 2011;

Corresponding author. Tel.: +49 421 218 66583; fax: +49 421 218 66573.

E-mail addresses: mschade@uni-bremen.de (M. Schade), s.hegner@utwente.nl

(S. Hegner), fhorstmann@uni-bremen.de (F. Horstmann), limsekr@uni-bremen.de

(N. Brinkmann).

1

Tel.: +31 53 489 2730; fax: +31 53 489 4259.

2

Tel.: +49 421 218 66580; fax: +49 421 218 66573.

3

Tel.: +49 421 218 66572; fax: +49 421 218 66573.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.08.003

0148-2963/ 2015 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Erikson, 1963). Following this theory, the increasing sense of one's

identity from adolescence to adulthood leads to value changes during

lifetime, and consequently, to a modication of the importance of individual needs and motivations (Gutman, 1982; Sheldon & Kasser, 2001).

Hellevik (2002) states that differences in value orientation between

age groups are larger than the differences found for any other social

background variable (p. 286). Assuming that identity-based motives

are particularly moderated by age (Erikson, 1963) and additionally assuming that those identity-based motives hold a strong reference with

luxury consumption (Bian & Forsythe, 2012; Stockburger-Sauer &

Teichmann, 2013), we expect that age inuences the motivations of

luxury brand purchasing in a very meaningful way. So far, research

does not provide adequate knowledge about the inuence of age on

luxury brand consumption.

In order to investigate the motivations for luxury consumption in

different age groups, the authors apply the Functional Theories of Attitudes as a conceptual framework (Eagly & Chaiken, 1998; Grewal,

Mehta, & Kardes, 2004; Katz, 1960; Shavitt, 1990; Smith, Bruner, &

White, 1956; Snyder & DeBono, 1989). These theories suggest that individuals possess attitudes due to the psychological benets they derive

from them (Gregory, Much, & Peterson, 2002; Grewal et al., 2004) and

that attitudes can serve different functions like expressing one's self

(Katz, 1960). The functional view of attitudes suggests that in order

for attitudes to change, brands need to appeal to the functions that a

particular attitude serves for the individual. Thus, the features of the

attitude object and their relationship to need satisfaction act as the

motivational underpinnings of attitudes (Lutz, 1978). Therefore, a

M. Schade et al. / Journal of Business Research 69 (2016) 314322

strong link between attitude functions and motivation exists (Sheth,

Newman, & Gross, 1991).

The Functional Theories of Attitudes are suitable for our study due

to the established fact that attitudes are an underlying variable that inuences behavior (e.g. consumer behavior) (Katz, 1960; Shavitt, 1989;

Smith et al., 1956). Prior studies have shown the relevance of attitude

functions (value-expressive, social-adjustive, hedonic, utilitarian) in

explaining consumer behavior (Grewal et al., 2004; Shavitt, 1990;

Wilcox, Kim, & Sen, 2009). In the context of luxury brand consumption,

several authors have proven the applicability of the Functional Theories of Attitudes as a conceptual framework (e.g. Bian & Forsythe,

2012; Seung-A, 2012; Wilcox et al., 2009). In order to reect the complexity of the attitude functions, we adopt the encompassing denition

of luxury brands by Hudders (2012, p. 609): Luxuries are brands with a

premium quality and/or an esthetically appealing design. In addition,

luxury brands are exclusive, which implies expensiveness and/or

rarity.

The objective of the present study is to analyze luxury brand responses (attitude functions and purchase behavior) with a special

focus on age groups. Thus, the following question arises: Which attitude

functions are particularly relevant for determining luxury brand consumption in different age groups? This research regards both similarities and differences in the inuence of attitude functions on luxury

brand responses among different age groups. Consequently, this study

will provide practical implications for the positioning of luxury brands

adapted to specic target groups in order to increase the efciency of

marketing activities.

The next section presents the Identity Development Process and

the Functional Theories of Attitudes. Connecting the two conceptual

frameworks, hypotheses are derived, followed by a presentation of the

research method and the results of the empirical study. The paper concludes with a discussion of the key ndings, management implications,

as well as limitations and directions for further research.

2. Conceptual framework

2.1. Identity development process

In order to investigate differences between age groups, most

researchers draw on life span research (e.g. Lesser & Kunkel, 1991;

Simpson & Licata, 2007; Waterman, 1982). The stage theory by

Erikson (1963), focusing on the Identity Development Process, is

one of the most accepted frameworks for life span research (Sheldon

& Kasser, 2001; Simpson & Licata, 2007; Waterman, 1982). Consequently, the present study uses this theory as conceptual foundation.

Personal identity is dened as the totality of one's self-construal

(Weinreich, 1986, p. 317). The basic assumption of identity development (Erikson, 1963; Sheldon & Kasser, 2001; Waterman, 1982) is

that the transition from adolescence to adulthood involves a progressive strengthening in the sense of identity. (Waterman, 1982, p. 342).

This increasing sense of one's identity leads to value changes during lifetime and to a modication of the relevance of human needs (Gutman,

1982; Sheldon & Kasser, 2001).

Based on the Identity Development Process (Erikson, 1963;

Sheldon & Kasser, 2001), the following periods of identity development

are present in Western societies: childhood (011 years), early and

middle adolescence (1215 years), late adolescence (1625 years),

young adulthood (2639 years), middle-aged adulthood (4059

years), and older adulthood (60 years and older). These age limits are

in line with a study by Lesser and Kunkel (1991) investigating consumer

behavior across the life span.

According to Kapes and Strickler (1975) as well as Rokeach

(1972), values and human needs tend to change considerably during

adolescence and young adulthood; however, they are generally quite

stable during middle and older adulthood due to the fact that in most

cases, the sense of identity remains stable after the age of 40 (Erikson,

315

1963; Sheldon & Kasser, 2001). Kapes and Strickler (1975) as well as

Rokeach (1972) come to the conclusion that only minor differences regarding the relevance of needs for middle-aged (4059 years) and older

adults (60 years and older) exist. As minor differences between these

two age groups might appear, the authors exclude older adults from

their sample and focus on the difference between late adolescents,

young adults, and middle-aged adults. Consequently, the present

study considers individuals with a minimum age of 16, as younger people mostly dispose a considerable low income, and therefore have limited possibilities to acquire luxury brands. Thus, this study investigates

the following life span periods: late adolescence, young adulthood,

and middle-aged adulthood. The focus is on the most relevant personal

differences among the considered three age groups.

In late adolescence (1625 years), humans search for their identity

and show mostly a weak sense of their own identity (Belk, 1988;

Erikson, 1963). Thus, individuals in their late adolescence primarily

strive for approval of their peer group. They feel pressured to conform

to the opinion and behavior of their social group in order to avoid an

outsider position (so-called peer pressure; Gil, Kwon, Good, &

Johnson, 2012; Wooten, 2006). Because of their weak sense of own

identity, late adolescents do not have the need to communicate their

own identity to others, if this identity is not in line with the peer group.

Contrary to late adolescents, young adults (2639 years) show a

stronger sense of their own identity and their behavior focuses less on

peer group acceptance (Erikson, 1963; Waterman, 1982). Due to the increased sense of identity, individuals in the young adulthood feel the

need to present their own identity to others and particularly to their reference or aspiration group (Erikson, 1963). Further, this age group

shows a relatively high willingness to take risks (Lambert-Pandraud &

Laurent, 2010; Lesser & Kunkel, 1991). Based on the Identity Development Process, young adults have especially the need to express their

own identity (Erikson, 1963). This assumption is in line with other theorists who state that young adults have a strong desire to demonstrate

personal achievement (Buhler, 1968; Kuhlen, 1964; Lesser & Kunkel,

1991). In this context, Stevenson (1977) uses the term active mastery

to describe these individuals' motivations to demonstrate their identity

and personal achievement.

Contrary, middle-aged adults (4059 years) are in most cases aware

and consolidated in their own identity (Erikson, 1963; Sheldon &

Kasser, 2001). Furthermore, Buhler (1968) argues that middle-aged

adults begin to accept their self-limitations by adopting a more passive perspective about their environment (Lesser & Kunkel, 1991).

As a consequence, these individuals are less concerned with identity

and the need to present their identity to others is less pronounced

(Erikson, 1963). Sheldon and Kasser (2001) empirically conrmed

this assumption by showing that the need for presenting the own

identity is on a lower level among middle-aged adults in comparison

to younger age groups.

Values and needs change during life span. Value orientations are

conceptions of the desirable (Kluckhorn, 1951). Parks and Guay

(2009) dene values as learned beliefs that serve as guiding principles about how individuals ought to behave (p. 676). Following

Gutman (1982), personal values determine the importance of

human needs. For example, if security is a personal value, as a consequence the need for group membership is of high importance. In

addition to values and needs, attitudes and motivations play an important role in determining consumer behavior. Attitudes and motivations distinguish from values and needs in the following way;

while attitudes and motivations specically relate to a given object,

person, behavior, or situation, values and needs are more ingrained,

more stable, and more general (England & Lee, 1974; Parks & Guay,

2009). Consequently, values and needs are inuencing object-related attitudes and motivations. In line with previous research, this

study analyzes motivations for luxury brand consumption based on

the Functional Theories of Attitudes (e.g. Bian & Forsythe, 2012;

Wilcox et al., 2009). The authors draw hypotheses based on the

316

M. Schade et al. / Journal of Business Research 69 (2016) 314322

changing value structures during lifetime by combining those general ndings with research on attitude functions to the specic context

of luxury consumption.

2.2. Functional theories of attitudes

The proposition in the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) that attitudes guide or inuence behavior applies to luxury brand consumption

(Ajzen, 1991). Fishbein and Ajzen (1975, p. 6)) dene attitude as a

learned predisposition to respond in a consistently favorable or unfavorable manner with respect to a given object. Similarly, the Functional Theories of Attitudes consider attitudes as an important variable in

order to explain consumer behavior and classies attitudes according

to the psychological functions that they serve (Grewal et al., 2004;

Katz, 1960; Shavitt, 1990; Smith et al., 1956; Wang, 2009; Wilcox

et al., 2009). While the TPB provides a framework for the relationship

between attitudes and behavior, the Functional Theories of Attitudes

enrich the model by differentiating several facets of attitudes (Wang,

2009). Therefore, our study applies the Functional Theories of Attitudes as conceptual framework in order to analyze different facets of

attitude as relevant underlying constructs that inuence consumer

behavior.

Social attitude functions (Shavitt, 1990) differ from more personally orientated functions like hedonic and utilitarian (Shavitt, 1990).

Social attitude functions are directly linked to personal identity and

play an important role in social interaction and self-expression.

Through those functions individuals express central values, establish their identity, and gain social approval (Katz, 1960; Shavitt,

1989; Smith et al., 1956). The social functions can be further distinguished in two dimensions: social-adjustive and value-expressive

(Grewal et al., 2004; Katz, 1960; Shavitt, 1989; Wilcox et al., 2009).

Literature links the social-adjustive function to the compliance

with peer pressure, while the value-expressive function is closely

related to the expression of one's own identity to a reference or aspiration group (Grewal et al., 2004; Katz, 1960; Shavitt, 1989; Wilcox

et al., 2009).

2.2.1. Social-adjustive function

The social-adjustive function is dened as a tendency to purchase

and use brands to gain approval in social situations and to maintain

relationships (Bian & Forsythe, 2012; Wilcox et al., 2009). This function is particularly relevant for consumers striving to meet the expectation of a peer group and gaining approval in social settings

(Grewal et al., 2004; Wilcox et al., 2009). According to Bearden,

Netemeyer, and Teel (1989,p. 474), the social-adjustive function is

essential for individuals with a tendency to conform to expectations

of others. Consumers with such a tendency are striving to purchase

the right brands which are accepted by their peer group. In Western societies, luxury brands are often the right brands and are

therefore used as a status symbol (Vigneron & Johnson, 2004;

Wilcox et al., 2009). Following the Identity Development Process

especially late adolescents (1625 years) experience the need to

align with their peer group (Belk, 1988; Erikson, 1963; Wooten,

2006), including purchasing the right brands their peers consume

(Gil et al., 2012). Consequently, the social-adjustive function is of

high predictive value for explaining luxury brand purchase behavior

of late adolescents. In contrast to this presumption, young adults

(2639 years) as well as middle-aged adults (4059 years) have a

stronger sense of their own identity and therefore place less emphasis on the expectations of peer groups (2011; Erikson, 1963; Sheldon

& Kasser, 2001).

H1. The relation between the social-adjustive function and luxury

brand purchase intention is stronger for late adolescents (1625

years) than a) for young adults (2639 years) and b) middle-aged

adults (4059 years).

2.2.2. Value-expressive function

A value-expressive function is dened as a tendency to purchase and

use brands to communicate one's self-identity (beliefs, attitudes,

values) to others (Bian & Forsythe, 2012; Wilcox et al., 2009). Consumers holding a value-expressive attitude toward a brand are motivated to consume it as a form of self-expression (Wilcox et al., 2009).

Hence, the value-expressive function is of high relevance for individuals

striving for communicating their self-identity to others, even if this is

not in line with the expectations of their peer group (Grewal et al.,

2004; Shavitt, 1990; Wilcox et al., 2009). Those consumers intend to

purchase brands that possess characteristics representing their identity

(Bian & Forsythe, 2012). Due to their outstanding value-expressive

function, luxury brands in particular enable consumers to communicate

specic facets of their identity (e.g. success, sophistication) to others

(Hudders, 2012; Vigneron & Johnson, 1999). According to the Identity

Development Process, young adults (2639 years) experience a strong

motivation for expressing their own identity (Erikson, 1963). Therefore,

the value-expressive function is of high importance for explaining luxury brand consumption of young adults. In contrast to this statement, late

adolescents (1625 years) show mostly a weak sense of their identity

and hence do not have the need to communicate their (widely unclear)

identity to others (Belk, 1988; Erikson, 1963). Middle-aged adults (40

59 years) begin to accept their self-limitations by adopting a more passive perspective about their environment (Lesser & Kunkel, 1991).

Therefore, the motivation for presenting their own identity is on a

lower level in comparison to young adults.

H2. The relation between the value-expressive function and luxury

brand purchase intention is stronger for young adults (2639 years)

than for a) late adolescents (1625 years) and b) middle-aged adults

(4059 years).

2.2.3. Hedonic function

Consumers purchasing brands for hedonic reasons enjoy sensory

pleasure, esthetic beauty, or excitement and consequently, arousing

feelings and affective states receiving personal rewards and fulllment

(Dubois & Laurent, 1994; Sheth et al., 1991; Voss, Spangenberg, &

Grohmann, 2003; Wiedmann, Hennigs, & Siebels, 2009). Dubois and

Laurent (1994) have shown that the hedonic function is of crucial importance for luxury brand consumption as it reects gratication and

sensory pleasure based on experience with the product. According to

the Identity Development Process, no indication exists that the need

for arousing feelings and affective states is more or less relevant for different age groups. In contrast, Dubois and Laurent (1994) point out that

a vast majority subscribes to the hedonic motive (p. 275). Therefore,

the relevance of the hedonic function should not differ among the age

groups.

H3. No signicant difference occurs between the age groups regarding

the inuence of the hedonic function on luxury brand purchase

intention.

2.2.4. Utilitarian function

Grewal et al. (2004) combine utilitarian and hedonic consequences

of consumption, while Voss et al. (2003) as well as Batra and Ahtola

(1990) call for a distinction of the utilitarian and hedonic function.

This suggestion is in line with recent luxury brand research investigating hedonic and utilitarian dimensions discretely in order to explain

luxury brand consumption (Shukla & Purani, 2012; Vigneron &

Johnson, 2004; Wiedmann et al., 2009).

The utilitarian dimension is derived from functions performed by

products (Voss et al., 2003). While the hedonic function focuses on providing an emotional experience, the utilitarian function relates to the

quality of goods and focuses on rational purposes (Batra & Ahtola,

1990; Tynan, McKechnie, & Chhuon, 2010; Voss et al., 2003). It is

M. Schade et al. / Journal of Business Research 69 (2016) 314322

mirrors the demographic composition of German adult population

concerning education and income.

concerned with how a brand performs a desired product- or servicerelated function (e.g. durability) (Voss et al., 2003). In the eld of luxury

consumption, it is assumed that luxury brands offer greater quality and

performance than non-luxury brands (Wiedmann et al., 2009). Shukla

and Purani (2012) show in an empirical study that the utilitarian function strongly inuences the purchase intention of luxury brands in

Western societies. Following the Identity Development Process, no

indication exists that the utilitarian function is more or less relevant

for different age groups. Therefore, the authors propose:

3.2. Construct development and equivalence

Development of the survey instrument began with a careful review

of the extant literature to identify relevant measures for attitude functions of luxury brands. These measures divide the survey into two different sections: the rst section contains attitude functions and luxury

purchase intention, while the second section focuses on demographics.

The study consists of items relating to the social-adjustive and valueexpressive functions of attitudes from Grewal et al. (2004). To measure

the hedonic and utilitarian functions, the validated scale of Voss et al.

(2003) applies. The authors do not draw on the measurement of the

utilitarian function by Grewal et al. (2004) due to the fact that these researchers merge the utilitarian and the hedonic function. The purchase

intention was measured within a time frame of 2 months using the scale

from Bansal and Taylor (2004). The true predictive validity of intentions

might get biased over time (Kalwani & Silk, 1982). In order to limit the

consequences of such a bias, the authors decided to apply a time frame

of 2 months. A complete list of items can be found in Table 1. For the

measures, the authors implemented a ve-point Likert-type response

format, with 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. To provide content validity of the survey, the authors followed the recommendation of Zaichkowsky (1985) by presenting the questionnaire to 5

researchers. Initially, the original questionnaire was in English, then

translated to German and modied as necessary to eliminate discrepancies between the two versions to verify the accuracy of the translation.

Translation back-translation method applies to ensure semantic

equivalence.

H4. No signicant difference occurs among the age groups regarding

the inuence of the utilitarian function on luxury brand purchase

intention.

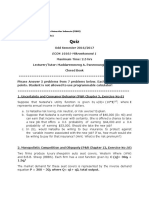

Fig. 1 summarizes the conceptual model of the present study.

3. Method

3.1. Sample and procedure

To determine product categories capturing the luxury brand domain, the authors conducted exploratory interviews with marketing researchers (n = 3) and luxury brand managers (n = 5). We provided our

denition of luxury brands (Hudders, 2012) to the experts. Based on

this denition, the experts stated product categories for luxury consumption, which are frequently purchased and consumers are familiar

with and have experience in. In addition, the experts mentioned prototypical luxury brands belonging to these categories (e.g. Hermes, Chanel, Fendi as typical luxury brands in the category clothes; Patek

Philippe, Rolex, and Breitling as typical luxury brands in the category

watches; Bugatti, Ferrari, Lamborghini as typical luxury brands in the

category cars). This list was provided to the respondents of the main

study for two reasons: (1) in order to communicate our understanding

of luxury brands to the participants and (2) to exclude participants who

have no luxury consumption experience in any of the categories.

In August and September 2013, a total of 576 respondents (main

study) participated in an online panel from a large pan-European market research agency. The sample of participants was actual luxury

brand consumers. After deleting cases with more than 10% missing

values, we had an effective sample size of 297 people. Of these,

20.3% were late adolescents (1625 years, n = 90), 35.3% were

young adults (2639 years, n = 105), and 34.4% middle-aged adults

(4059 years, n = 102) with a mean age of 34.1. The sample is well

balanced in terms of gender across the age groups and closely

Social-adjustive

function of attitudes

317

4. Analyses and ndings

Partial least square (PLS) path modeling tests the hypothesized

research model. PLS method is a non-traditional alternative to

covariance-based structural equation modeling (Lohmller, 1989;

Ringle, Wende, & Will, 2005). In PLS, structural models use an iterative

procedure which maximizes the strength of the relationship between

independent and dependent variables. Unlike covariance-based approaches, PLS works well with small samples (Chin, 1998; Wold,

1982). SmartPLS 2.0 estimates the hypothesized model (Ringle et al.,

2005). In addition, a bootstrap resampling procedure tests the model

stability (297 cases, 5000 samples).

Age

Value-expressive

function of attitudes

Luxury brand purchase

intention

Hedonic

function of attitudes

Utilitarian

function of attitudes

Fig. 1. Conceptual model.

318

M. Schade et al. / Journal of Business Research 69 (2016) 314322

Table 1

Reliability and convergent validity.

Variables

Item

t-statistics CR

loading

Social-adjustive function

SA1: It is important for my friends to know the

.62

11.71

luxury brands I possess.

SA2: Luxury brands are a symbol of social status. .67

12.95

SA3: Luxury brands help me in tting into

.74

15.29

important social situations.

SA4: I like to be seen with my luxury brands.

.85

34.74

SA5: The luxury brand that a person owns, tells me .31

2.97

a lot about that person.a

SA6: My luxury brand indicates to others the

.73

14.70

kind of person I am.

Value-expressive function

VE1: Luxury brands reect the kind of person I

.83

27.20

see myself to be.

VE2: Luxury brands ascertain my self-identity.

.80

23.25

VE3: Luxury brands make me feel good about

.80

28.07

myself.

VE4: Luxury brands are an instrument of my

.84

36.00

self-expression.

VE5: Luxury brands play a critical role in dening .76

17.55

my self-concept

VE6: Luxury brands help me to establish the kind .84

26.38

of person I see myself to be.

Hedonic function

Luxury brands offer the following characteristics to me

HD1: not fun / fun

.85

44.64

HD2: dull / exciting

.86

45.30

HD3: not delightful / delightful

.85

37.82

HD4: not thrilling / thrilling

.86

44.29

HD5: enjoyable / unenjoyable

.70

15.44

Utilitarian function

Luxury brands offer the following characteristics to me

UT1: effective / ineffective

.74

17.84

UT2: helpful / unhelpful

.76

18.86

UT3: functional / not functional

.66

11.09

UT4: necessary / unnecessary

.64

11.46

UT5: practical / impractical

.72

15.73

Purchase intention

How likely is it that you purchase a luxury brand within the next 2

months?

PI1: unlikely / likely

.94

66.44

PI2: no chance / certain

.93

77.82

PI3: improbable / probable

.95

109.84

AVE

.85 .53

.92 .66

.92 .68

in the measure range from .62.95, and exceed the threshold. At the

construct level, Hair et al. (2006) recommend to regard composite reliability instead of Cronbach's alpha. Additionally, average variance extracted measures the amount of variance captured by the construct in

relation to the amount of variance attributable to measurement error

(Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Together, these measures represent a good indication of the convergent validity of the constructs. The average variance extracted (AVE) is adequate for all the factors (N.50) (Fornell &

Larcker, 1981). Additionally, composite reliabilities (CR) are all higher

than .60 (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988) and therefore exceed the threshold. The

measures fulll the FornellLarcker criterion as all squares of parameter

estimates between factors are less than their average variance extracted

estimates. For adequate discriminant validity, the diagonal elements in

Table 2 should be greater than the off-diagonal elements (Fornell &

Larcker, 1981). Comparing all correlation coefcients with square

roots of AVEs in Table 2, the results suggest evidence of discriminant validity. Additionally, all constructs positively relate to each other.

Bivariate correlations between each of the variables are measured

(see Table 3). The results show that all correlations are signicant

(p b .01). Bollen and Lennox (1991) recommend high or moderate correlations of effect indicators within a latent variable. In the presented

study, most of the correlations of the effect indicators within a latent

variable show a high correlation (exceeds .4). No correlation of these indicators within a latent variable is under the level of .2 (low correlation).

4.2. Structural model and multi-group analysis

.83 .50

.96 .88

CR = composite reliability; AVE = average variance extracted

a

Excluded from further analysis

4.1. Measurement model

Prior to testing the structural relationships, exploratory and conrmatory factor analyses serve to pretest the measures and ensure the robustness of the selected scale structures. Conrmatory factor analysis

establishes convergent and discriminant validity. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics as well as reliability and validity measures of the constructs social-adjustive (SA), value-expressive (VE), hedonic (HD),

utilitarian (UT), and purchase intention (PI). During this process, the authors eliminated one item (SA5) due to very low factor loading. Hair,

Black, Babin, and Anderson (2006) propose that an item is signicant

if its factor loading is greater than .50. The factor loadings of the items

R2 estimates, standardized path coefcients (), and signicance

level (t-statistic) evaluate the structural model. R2 values measure the

structural model's predictive power, while path loadings indicate the

strength between independent and dependent variables. R2 coefcients

exceed the recommended .10 value (Falk & Miller, 1992) suggesting the

structural model exhibits adequate explanatory power. Specically, the

explained percentage of purchase intention in the late adolescent

segment is R2 = .31, in the young adults segment R2 = .26, and in the

middle-aged adults segment R2 = .19. A PLS algorithm and

bootstrapping procedure calculates path loadings and t-statistics for

the hypothesized relationships.

To compare the ndings from three distinct samples, namely, late

adolescents (1625 years), young adults (2639 years), and middleaged adults (4059 years) of the inuence of attitude functions on luxury brand purchase intention, the authors performed a multi-group

analysis (see Table 3).

In order to test the moderator hypotheses, the authors analyze

whether the observed path coefcients of each function signicantly

differ from each other among the three age groups. The authors applied

the PLS-MGA approach of Henseler (2007) to test for differences between the age groups. Table 4 provides the signicance level of the

group comparisons for each function.

The results show that the path coefcient regarding the relationship

between the social-adjustive function and purchase intention is signicantly higher (p b .01) in the late adolescent ( = .26, p b .05) compared

to the young adult sample ( = .17, p N .05) conrming H1a. While

the social-adjustive function shows the highest impact on purchase intention in the late adolescent group, a negativethough not statistically

Table 2

Discriminant validity: inter-construct correlations.

Construct

Social-adjustive

Value-expressive

Hedonic

Utilitarian

Purchase intention

Social-adjustive

Value-expressive

Hedonic

Utilitarian

Purchase intention

.73

.69

.42

.42

.31

.81

.44

.42

.34

.82

.58

.39

.71

.38

.94

All correlations are signicant at p b 0.01. Bold data indicates the square roots of AVE.

M. Schade et al. / Journal of Business Research 69 (2016) 314322

319

Table 3

Correlation matrix of all variables.

PI1

PI2

PI3

VE1

VE2

VE3

VE4

VE5

VE6

UT1

UT2

UT3

UT4

UT5

HED1

HED2

HED3

HED4

HED5

SA1

SA2

SA3

SA4

SA5

PI1

PI2

PI3

VE1

VE2

VE3

VE4

VE5

VE6

UT1

UT2

UT3

UT4

UT5

HED1

.79

1

.86

.80

1

.23

.24

.25

1

.18

.18

.21

.65

1

.34

.36

.37

.52

.51

1

.28

.25

.30

.68

.63

.57

.21

.16

.21

.58

.56

.51

.55

.22

.15

.23

.70

.65

.58

.62

.61

.25

.24

.24

.17

.24

.9

.17

.19

.24

.29

.30

.33

.13

.15

.33

.24

.19

.26

.39

.19

.18

.21

.29

.19

.30

.21

.20

.31

.42

.38

.29

.24

.24

.27

.19

.34

.27

.28

.30

.27

.44

.24

.22

.26

.23

.18

.24

.28

.20

.20

.20

.56

.33

.46

.25

1

.27

.39

.30

.23

.22

.38

.23

.21

.24

.36

.43

.27

.25

.40

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

HED2

.27

.38

.29

.26

.27

.40

.23

.19

.29

.30

.37

.25

.26

.30

.67

1

HED3

HED4

.30

.36

.30

.36

.36

.53

.34

.27

.35

.40

.37

.32

.34

.41

.62

.66

1

.28

.32

.29

.28

.28

.49

.26

.20

.33

.32

.49

.30

.30

.39

.66

.71

.70

1

signicantimpact of social-adjustiveness occurs for the young

adults. No signicant difference (p N .05) on this parameter between

the late adolescents and the middle-aged adults ( = .06, p N .05) exists (Table 5). Thus, H1b cannot be conrmed. In the consumer group

of middle-aged adults, the social-adjustive function is not relevant

for the purchase intention of luxury brands. Thus, a signicant difference between the young adults and the middle-aged adults exists.

Regarding the path coefcients between the value-expressive

function and purchase intention, signicant differences between

the age segments are present. The young adults ( = .39, p b .05)

group shows signicantly stronger effects than the two other

samples. Therefore, the results conrm H2a and b. The valueexpressive function even has the highest impact of all functions on

purchase intention for the young adults. Both for late adolescents

( = .03, p N .05) and middle-aged consumers ( = .08, p N .05),

the impact of value-expressiveness on purchase intention is not

signicant.

The inuence of hedonism and utilitarianism on purchase intention

is equally strong in all three groups, conrming H3 and H4. While the

hedonic function shows a signicant impact on purchase intention for

the late adolescents ( = .21, p b .05) and the middle-aged adults

( = .21, p b .05), no signicant effect exists for the young adults

( = .13, p N .05). The utilitarian function is highly signicant for the

purchase intention in all three segments. For the middle-aged adults

( = .19, p b .05), the utilitarian function is the most relevant of all functions for their purchase intention. But also in the late adolescent ( =

.25, p b .05) and young adult ( = .24, p b .05) segment, the signicance

level is below .05 and therefore highly signicant.

HED5

SA1

SA2

SA3

SA4

SA5

.21

.26

.26

.19

.12

.33

.18

.13

.16

.30

.36

.38

.12

.36

.54

.48

.50

.48

1

.18

.10

.22

.25

.37

.33

.32

.34

.28

.07

.18

.12

.17

.11

.08

.10

.18

.09

.05

1

.13

.18

.17

.31

.28

.35

.33

.37

.31

.19

.28

.29

.22

.16

.25

.26

.29

.30

.21

.25

1

.15

.14

.21

.40

.31

.42

.33

.38

.40

.21

.26

.14

.23

.09

.21

.16

.31

.26

.21

.42

.40

1

.30

.29

.33

.50

.50

.61

.46

.48

.49

.28

.30

.27

.31

.22

.34

.38

.49

.43

.25

.40

.45

.53

1

.21

.15

.22

.52

.46

.41

.53

.46

.49

.17

.23

.26

.22

.22

.20

.18

.27

.23

.15

.33

.47

.44

.47

1

5. Discussion

According to life span research, individuals' motivations change

through their lifetime. Previous research on luxury brand consumption

neglected this phenomenon. Based on the ndings of this study, the results conrm that the relevance of attitude functions for luxury brand

purchase differs among age groups. This research is the rst study empirically proving a moderation effect of age in the context of luxury

brand consumption.

Furthermore, the aim of this study is the identication of differences

and commonalities of the relevance of attitude functions on luxury consumption in different age groups. While the utilitarian attitude function

shows a high relevance for all age groups, the hedonic function seems to

be particularly of inuence on purchase intention for late adolescents

(1625 years) and middle-aged adults (4059 years). In contrast to

this nding, social-adjustive function is only signicant for late adolescents and the value-expressive function only signicant for young

adults.

The social-adjustive function seems to be exclusively relevant for

late adolescents supporting the theoretical assumption that peer pressure is particularly shaping the behavior of this target group. Contrary,

for young adults, a negative though not statistically signicant effect of

this function on purchase intention is evident. The strong focus on identity expression of young adults indicates a need for distinction from

their peer group. For middle-aged adults, complying to peer pressure

is of no inuence on luxury consumption. No indication that socialadjustiveness has any relevance for middle-aged consumers occurs,

while it seems of great importance for late adolescents. The small

Table 4

Summary of the standardized parameter estimates, t-statistics, and p-values of the structural model for the overall sample as well as the three age groups.

Social-Adjustive Purchase Intention

Value-Expressive Purchase Intention

Hedonic Purchase Intention

Utilitarian Purchase Intention

Note: Values in parentheses are t-values and p-values.

Late adolescents

Young adults

Middle-aged adults

.26 (2.04; .04)

.03 (.39; .70)

.23 (2.38; .02)

.25 (2.54; .01)

.17 (1.50; .10)

.39 (2.71; .01)

.13 (1.53; .10)

.24 (2.46; .02)

.06 (1.15; .25)

.08 (1.12; .27)

.21 (2.91; .00)

.19 (2.70, .01)

320

M. Schade et al. / Journal of Business Research 69 (2016) 314322

Table 5

Comparative results of the multi-group analysis represented by p-values.

Social-Adjustive Purchase Intention

Value-Expressive Purchase Intention

Hedonic Purchase Intention

Utilitarian Purchase Intention

Late adolescents vs. young adults

Late adolescents vs. middle-aged adults

Young adults vs. middle-aged adults

.01

.02

.22

.49

.14

.09

.41

.24

.01

.01

.20

.29

Bold data indicates p b 0.05.

sample size might have an inuence on the fact that this study shows no

signicant differences between late adolescents and middle-aged adults

concerning the inuence of social-adjustiveness. Future research needs

to explore this effect in greater detail.

The value-expressive function is only of inuence for young adults.

This nding conrms the underlying theory of the Identity Development Process showing that in a period of experiencing a stronger consciousness of one's own self-identity, individuals have especially the

need to express themselves.

Bian and Forsythe's (2012) study shows only a marginally signicant

effect for a combined social function in the late adolescent group. As the

ndings of this study demonstrate, a separation of the social-adjustive

and value-expressive function is advisable. While the social-adjustive

function inuences luxury brand purchase intention in late adolescents,

young adults reject peer pressure, and therefore the only social function

that shows signicance is value-expressiveness in this group.

The study of Dubois and Laurent (1994) claims a strong inuence of

the hedonic function on luxury consumption across target groups. The

ndings only partially support this claim as the impact does not hold

true in the young adult group. Given the fact that identity expression

dominates the luxury consumption behavior in this target group, the

hedonic function becomes less relevant.

Grewal et al. (2004) stated that the utilitarian function plays a less

prominent role for luxuries. In contrast to this, Tynan et al. (2010)

come to the conclusion that a high standard of quality is essential for

all luxury goods. Based on the results of our study the utilitarian function shows a high relevance across all three age groups. A possible explanation can be found drawing on Herzberg's (1959) motivation

hygiene theory. Adopting this theory, quality can be perceived as a

hygiene factor for luxury brands (Brun & Castelli, 2013); therefore, consumers expect an outstanding quality. In case those high expectations

stay unfullled, consumers might be dissatised and refrain from

(re)purchasing the brand. Concluding, quality seems necessary but not

sufcient. Thus, quality might not in itself drive luxury purchase behavior, brand positioning should always be complemented by social and

hedonic aspects.

To conclude, the personal attitude functions (hedonic and utilitarian) are in principle relevant across all age groups, while the impact of

the social functions greatly differ among the target groups. Whereas

the social-adjustive function strongly enhances luxury brand purchase

behavior of late adolescents, value-expressiveness only impacts the luxury consumption of young adults. Social functions do not determine the

acquisition of luxury brands for middle-aged adults. Based on the results, luxury brands are identity supporting brands for late adolescents and young adults; however, these social functions do not show

any relevance for middle-aged adults.

6. Practical implications

The ndings suggest that managers need to develop an age group

specic competitive marketing strategy concerning the positioning of

luxury brands, particularly focusing on age group specic adjustments

of the social functions.

As the results show, brand positioning should always be a specic

combination of utilitarian, social, and hedonic aspects to address the different age groups. As mentioned above, the utilitarian function (quality)

might act as a hygiene factor for luxury brands, thus in order to reach a

competitive advantage, a brand should additionally be positioned on

the hedonic and/or social functions. Especially to address late adolescents and young adults, the social function could provide a decisive

competitive advantage. To position a luxury brand particularly the social functions offer versatile options for designing brand communication

along the brand personality (e.g. elegant, sportive, or trendy).

This study provides evidence that luxury shopping motives of late

adolescents are highly inuenced by the social-adjustive function.

Luxury brand manufacturers can use this nding to leverage their

brands by popularizing their trademark through the use of testimonials,

idols, or role models to reach the opinion leaders of this target group.

Carrying the well-known Monogram canvas bags by famous celebrities

like Rihanna, Kim Kardashian, and Lady Gaga from the French manufacturer, Louis Vuitton has strengthened its positive image to attract late

adolescents all over the world.

Young adults communicate their self-identities to others by using

brands serving the value-expressive function. For luxury companies,

understanding the identity of this target group and communicating

the corresponding characteristics are essential. Concerning the socialadjustive and the value-expressive function, highlighted signatures

like logos, brand names, or predominant designs that identify luxury

brands deliver consumers' desire to satisfy these social needs.

For middle-aged adults, only hedonic and utilitarian aspects of the

brand are important for purchasing luxury goods. The desire to express

their self-identity or their expectations of how others will react to their

purchase decisions does not direct their luxury brand consumption.

Luxury brand managers face the challenge to address this target group

with a hedonic and utilitarian function which is part of the product

characteristics. Patek Philippe targets this age group by offering watches

with outstanding longevity (utilitarian) and unique design (hedonic).

Besides focusing on one age group in luxury brand positioning, managers face the opportunity to include sub-brands incorporating a specific target group in their brand portfolio. For example, the Polo Ralph

Lauren Corporation has become one of the most famous luxury brands

in the world by launching age group specic brands. By establishing

the Polo Ralph Lauren line with the polo player as explicit logo, they

were able to serve the social aspirations of their young consumers.

Introducing the purple and black label for more mature consumers in

1996 with the focus on quality and hedonic aspects, Polo Ralph Lauren

made a deliberate decision not to use a visible brand logo.

7. Limitations and further research

The goal of our study was the identication of underlying motives

for luxury brand consumption among age groups. Our ndings show

that the impact of the social functions greatly differs among the groups.

It is conceivable that age not only moderates motives for luxury

consumption but also the actual perception of what luxury constitutes.

In literature various facets of the luxury concept are discussed, e.g.

conspicuousness, uniqueness, craftsmanship, scarcity, ancestral heritage, long history (Dubois, Laurent, & Czellar, 2001; Kapferer, 1998;

Vigneron & Johnson, 1999). For instance, the perception of conspicuousness as a constituting facet of the concept of luxury might change over

the life span. As identity development research suggests, elderly individuals begin to accept their self-limitations by adopting a more

M. Schade et al. / Journal of Business Research 69 (2016) 314322

passive perspective about their environment including a strong focus

on the private (Lesser & Kunkel, 1991). Following this argument, elderly

consumers are likely to have more personal and private associations

with luxury. Therefore, conspicuousness might not be a facet that elderly consumers automatically associate with luxury. Whether age actually

inuences the perception of the luxury concept would offer an interesting research question for future studies.

Furthermore, not only does the interplay between motivations of

luxury consumption and the perception of the concept of luxury represent an appealing eld of research, but it would also be interesting to investigate the inuence of values and needs on motivations and the

perception of luxury among age groups. For instance, analyzing whether

attitude functions and the perception of luxury mediate the relationship

between values/needs and luxury purchase behavior seems to be an interesting venue.

Additionally, the vast majority of prior research on luxury brand

consumption takes a rather narrow focus regarding their age samples.

The present study broadens this perspective by including participants

from 16 to 59 years. Considering the great inuence of age on the relation between attitude functions and luxury brand purchase intention,

further research has to take age as a moderator into account. Especially

middle-aged adults represent an under-researched age group and,

therefore, might be of interest for further research. Based on theoretical

considerations, the authors assume no difference in the inuence of

attitude functions on luxury brand purchase intention between

middle-aged and older adults. Future research needs to conrm this

assumption.

Based on the results of the presented study, the relation between social functions and purchase intention is particularly moderated by age

(Erikson, 1963; Sheldon & Kasser, 2001). Our research focuses on the

luxury context only. Assuming that identity-based motives (social functions) might also hold a reference with non-luxury brand consumption,

it can be expected that age inuences the relevance of the social functions for non-luxury brand purchasing as well. In future research, investigating the inuence of age on the behavioral relevance of attitude

functions comparing luxury and non-luxury brands seems to be an interesting venue.

Furthermore, the application of a wide range of product categories

allows us to draw generalizable conclusions. However, for future

research, an investigation of the interplay between age and luxury product categories offers exceeding, more specic insights. Similarly, different luxury product categories have different purchase cycles. In our

study, purchase intention was measured within a time frame of 2

months. In future research, an adaptation of the purchase intention

time frame to the specic purchase cycle of the product would be advisable. Thereby, distinguishing buying behavior based on impulse versus

long-term planning could additionally be considered in future research.

The present study includes the assumption that the buyer and consumer of the luxury brand is one and the same person. The relevance of the

attitude functions might change if the buyer purchases luxury brands

for another person of different age (e.g. a father purchases a luxury

brand for his daughter's birthday). Comparing the relevance of attitude

functions for the two conditions (buying for yourself and buying for another person) offers a possibility for future research.

The present study demarcates the life spans according to age. To be

even more precise in differentiating life spans, researchers might consider characteristics like family status and career status. Cultural setting

is an additional factor for future research, as life span classications

might vary across different cultures. Further, the systematic exploration

of the inuence of culture on the relationship between attitude function

and luxury brand consumption is advisable.

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human

Decision Processes, 50, 179211.

321

Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of

the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 7494.

Bansal, H. S., & Taylor, S. F. (2004). A three-component model of customer commitment to service providers. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 32(3),

234250.

Batra, R., & Ahtola, O. T. (1990). Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian sources of consumer attitudes. Marketing Letters, 2(2), 159170.

Bearden, W. O., Netemeyer, R. G., & Teel, J. E. (1989, March). Measurement of consumer

susceptibility to interpersonal inuence. Journal of Consumer Research, 15, 473481.

Belk, R. W. (1988, September). Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer

Research, 15, 139168.

Bian, Q., & Forsythe, S. (2012). Purchase intention for luxury brands: A cross cultural comparison. Journal of Business Research, 65, 14431451.

Bollen, K., & Lennox, R. (1991). Conventional wisdom on measurement: A structural

equation perspective. Psychological Bulletin, 110(2), 305314.

Brun, A., & Castelli, C. (2013). The nature of luxury: A consumer perspective. International

Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 41(11/12), 823847.

Buhler, C. (1968). The general structure of human life cycle. In C. Buhler, & F. Mossarik

(Eds.), The Course of Human Life: A Study of Goals in the Humanistic Perspective

(pp. 1226). New York: Springer.

Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In

G. A. Marcoulides (Ed.), Modern Methods for Business Research (pp. 295328).

Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erbaum Associates.

Diehl, M., & Hay, E. L. (2011). Self-concept differentiation and self-concept clarity across

adulthood: Associations with age and psychological well-being. International Journal

of Aging and Human Development, 73(2), 125152.

Dubois, B., & Laurent, G. (1994). Attitudes toward the concept of luxury: An exploratory

analysis. Asia-Pacic Advances in Consumer Research, 1(2), 273278.

Dubois, B., Laurent, G., & Czellar, S. (2001). Consumer rapport to luxury: Analyzing complex and ambivalent attitudes. HEC School of Management, Jouy-en-Josas: Working

Paper (pp. 736).

Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1998). Attitude structure and function. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T.

Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of Social Psychology (pp. 269322). New York:

McGraw-Hill.

England, G. W., & Lee, R. (1974). The relationship between managerial values and managerial success in the United States, Japan, India, and Australia. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 59, 411419.

Erikson, E. (1963). Childhood and society. New York: Norton.

Falk, R. F., & Miller, N. B. (1992). A primer for soft modelling. Akron, OH: University of Akron

Press.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to

theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981, August). Structural equation models with unobservable

variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing

Research, 18, 382388.

Gil, L. A., Kwon, K. -N., Good, L. K., & Johnson, L. W. (2012). Impact of self on attitudes toward luxury brands among teens. Journal of Business Research, 65, 14251433.

Gregory, G. D., Much, J. M., & Peterson, M. (2002). Attitude functions in consumer research: comparing value-attitude relations in individualistic and collectivistic cultures. Journal of Business Research, 55, 933942.

Grewal, R., Mehta, R., & Kardes, F. R. (2004, February). The timing of repeat purchases of

consumer durable goods: The role of functional bases of consumer attitudes. Journal

of Marketing Research, 41, 101115.

Gutman, J. (1982, Spring). A meansend chain model on consumer categorization processes. Journal of Marketing, 46, 6072.

Hair, J. F., Jr., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2006). Multivariate data analysis

(6th ed.). Upper Sadle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall International.

Halpert, J. (2012). Millennials: young, broke, and spending on luxury. The Fiscal Times.

http://www.thescaltimes.com (26.08.2014)

Hellevik, O. (2002). Age differences in value orientation life cycle or cohort effects?

International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 14(3), 286302.

Henseler, J. (2007). A new and simple approach to multi-group analysis in partial least

squares path modeling. In H. Martens, & T. Ns (Eds.), Causalities explored by indirect

observation. Oslo: Proceedings of the 5th international symposium on PLS and related

methods. (pp. 104107).

Herzberg, F. M. (1959). The motivation to work. New York: Wiley.

Hudders, L. (2012). Why the devil wears Prada: Consumers purchase motives for luxuries. Journal of Brand Management, 19(7), 609622.

Kalwani, M. U., & Silk, A. J. (1982). On the reliability and predictive validity of purchase

intention measures. Marketing Science, 1(3), 243286.

Kapes, J. T., & Strickler, R. E. (1975). A longitudinal study of change in work values between 9th and 12th grades. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 6, 8193.

Kapferer, J. -N. (1998). Why are we seduced by luxury brands ? Journal of Brand

Management, 6, 4449.

Katz, D. (1960). The functional approach to the study of attitudes. Public Opinion

Quarterly, 24(2), 163204.

Kluckhorn, C. (1951). Values and value orientations in the theory of action. In Shils

Parsons (Ed.), Toward a general theory of action (pp. 388433). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kuhlen, R. G. (1964). Personality change with age. In P. Worckel, & D. Byrne (Eds.), Personality Change (pp. 524555). New York: Wiley.

Lambert-Pandraud, R., & Laurent, G. (2010, July). Why do older consumers buy older

brands? The role of attachment and declining innovativeness. Journal of Marketing,

74, 104121.

Lesser, J. A., & Kunkel, S. R. (1991). Exploratory and problem-solving consumer behavior

across the life span. Journal of Gerontology, 46(5), 259269.

322

M. Schade et al. / Journal of Business Research 69 (2016) 314322

Lohmller, J. B. (1989). Latent variable modelling with partial least squares. Heidelberg:

Physica-Verlag.

Lutz, R. J. (1978). A functional approach to consumer attitude research. Advances in

Consumer Research, 5, 360369.

Parks, L., & Guay, R. P. (2009). Personality, values, and motivation. Personality and

Individual Differences, 47(7), 675684.

Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Will, S. (2005). SmartPLS 2.0 (M3) Beta. Hamburg. http://www.

smartpls.de

Roberts, A. (2014). Luxury Growth at Risk as Shoppers Become More Diverse, Bain Says.

Bloomberg. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-01-14/luxury-growth-at-riskas-shoppers-become-more-diverse-bain-says.html (26.08.2014)

Rokeach, M. (1972). Beliefs, attitudes, and values: A theory of organization and change. San

Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc.

Roland Berger Strategy Consultants (2012). Roland Berger study on the luxury goods

market: Germany has the biggest potential in Europe. http://www.rolandberger.

com/press_releases/512-press_archive2012_sc_content/Roland_Berger_study_on_

luxury_goods_market.html (01.09.2014)

Seung-A, A. J. (2012). The potential of social media for luxury brand management.

Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 30(7), 687699.

Shavitt, S. (1989). Products, personalities and situations in attitude functions: Implications for consumer behavior. Advances in Consumer Research, 16, 300305.

Shavitt, S. (1990). The role of attitude objects in attitude functions. Journal of Experimental

Social Psychology, 26, 124148.

Sheldon, K. M., & Kasser, T. (2001). Getting older, getting better? Personal strivings and

psychological maturity across the life span. Development Psychology, 37(4), 491501.

Sheth, J. N., Newman, B. I., & Gross, B. L. (1991). Why we buy what we buy: A theory of

consumption values. Journal of Business Research, 22, 159170.

Shukla, P., & Purani, K. (2012). Comparing the importance of luxury value perceptions in

cross-national contexts. Journal of Business Research, 65, 14171424.

Simpson, P. M., & Licata, J. W. (2007). Consumer attitudes toward marketing strategies

over adult life span. Journal of Marketing Management, 23(3-4), 305326.

Smith, M. B., Bruner, J. S., & White, R. W. (1956). Opinions and personality. New York:

Wiley.

Snyder, M., & DeBono, K. G. (1989). A functional approach to attitudes and persuasion. In

M. P. Zanna, J. M. Olson, & C. Herman (Eds.), Social Inuence: The Ontario Symposium,

Vol. 5. (pp. 107128). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates.

Stevenson, J. S. (1977). Issues and crises during middlescence. New York: Appleton

Century-Crofts.

Stockburger-Sauer, N. E., & Teichmann, K. (2013). Is luxury just a female thing? The role

of gender in luxury brand consumption. Journal of Business Research, 66, 889896.

Tynan, C., McKechnie, S., & Chhuon, C. (2010). Co-creating value for luxury brands. Journal

of Business Research, 63, 11561163.

Vigneron, F., & Johnson, L. W. (1999). A review and a conceptual framework of prestige

seeking consumer behavior. Academy of Marketing Science Review, 1, 115.

Vigneron, F., & Johnson, L. W. (2004). Measuring perceptions of brand luxury. Journal of

Brand Management, 11(6), 484508.

Voss, K. E., Spangenberg, E. R., & Grohmann, B. (2003). Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian dimensions of consumer attitude. Journal of Marketing Research, 40, 310320.

Wang, X. (2009). Integrating the theory of planned behavior and attitude functions: Implications for health campaign design. Health Communication, 24, 426434.

Waterman, A. S. (1982). Identity development from adolescence to adulthood: An extension of theory and a review of research. Developmental Psychology, 18(3), 341358.

Weinreich, P. (1986). The operationalisation of identity theory in racial and ethnic relations. In J. Rex, & D. Mason (Eds.), Theories of Race and Ethnic Relations

(pp. 99320). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Wiedmann, K. -P., Hennigs, N., & Siebels, A. (2009). Value-based segmentation of luxury

consumption behavior. Psychology & Marketing, 26(7), 625651.

Wilcox, K., Kim, H. M., & Sen, S. (2009, April). Why do consumers buy counterfeit luxury

brands? Journal of Marketing Research, 46, 247259.

Wold, H. (1982). Soft modeling: The basic design and some extensions. In H. G. Jreskog,

& H. Wold (Eds.), Systems under indirect observation, part II (pp. 154). New York:

North-Holland Publishing.

Wooten, D. B. (2006). From labeling possessions to possessing labels: Ridicule and socialization and adolescents. Journal of Consumer Research, 33(2), 188198.

Zaichkowsky, J. L. (1985). Measuring the involvement construct. Journal of Consumer

Research, 12(3), 341352.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Nciii Bookkeeping PDFDocumento28 pagineNciii Bookkeeping PDFStephanie Cruz100% (9)

- 2018 11 30 - RecoilDocumento204 pagine2018 11 30 - RecoilTom Well0% (2)

- Schwartz Portrait Values QuestionnaireDocumento61 pagineSchwartz Portrait Values Questionnairepeterjeager100% (3)

- Cross Cultural EthicsDocumento23 pagineCross Cultural EthicsSerap CaliskanNessuna valutazione finora

- Career Counseling: Holism, Diversity, and StrengthsDa EverandCareer Counseling: Holism, Diversity, and StrengthsNessuna valutazione finora

- Pestle AnalysisDocumento4 paginePestle AnalysisRizza PanicanNessuna valutazione finora

- Aaker 1997 Brand PersonalityDocumento38 pagineAaker 1997 Brand PersonalityMichelle BuergerNessuna valutazione finora

- The Mcdonaldsindia: Optimizing The French Fries Supply ChainDocumento10 pagineThe Mcdonaldsindia: Optimizing The French Fries Supply ChainNaman TuliNessuna valutazione finora

- Dall MillDocumento27 pagineDall Millatulfamily0% (1)

- The Role and Measurement of Attachment in Consumer BehaviourDocumento20 pagineThe Role and Measurement of Attachment in Consumer BehaviourCarolinneNessuna valutazione finora

- Comparision Between Online & Offline ShoppingDocumento57 pagineComparision Between Online & Offline ShoppingSarita Sonar93% (15)

- Spain Consumer Values & SegmentationDocumento32 pagineSpain Consumer Values & Segmentationsheeba_roNessuna valutazione finora

- 7 - Imr2018-Individual-LevelculturalcestylesDocumento39 pagine7 - Imr2018-Individual-LevelculturalcestylesFajrillah FajrillahNessuna valutazione finora

- Impact of Self On Attitudes Toward Luxury Brands Among TeensDocumento10 pagineImpact of Self On Attitudes Toward Luxury Brands Among TeensLuciana De Araujo GilNessuna valutazione finora

- 10 1016-j Annals 2006 01 006Documento20 pagine10 1016-j Annals 2006 01 006weal_h_nNessuna valutazione finora

- Elderly Consumers in Marketing Research A Systematic Literature Review andDocumento25 pagineElderly Consumers in Marketing Research A Systematic Literature Review andsaddamNessuna valutazione finora

- Value Differences Betwen Generation X and Millennials: Arief - Helmi@unpad - Ac.idDocumento8 pagineValue Differences Betwen Generation X and Millennials: Arief - Helmi@unpad - Ac.idJogie SuhermanNessuna valutazione finora

- Elderly Consumers in Marketing Research A SystematDocumento25 pagineElderly Consumers in Marketing Research A SystematXUEYAN SHENNessuna valutazione finora

- Conceptual Framework and Hypothesis DevelopmentDocumento7 pagineConceptual Framework and Hypothesis DevelopmentSaba QasimNessuna valutazione finora

- Literature Review Culture ChangeDocumento6 pagineLiterature Review Culture Changejyzapydigip3100% (1)

- Cultural Dimensions and the Interchangeability of CSR and CE ConceptsDocumento23 pagineCultural Dimensions and the Interchangeability of CSR and CE ConceptsPeerzada BasimNessuna valutazione finora

- The Correlation of CSR and Consumer Behavior: A Study of Convenience StoreDocumento15 pagineThe Correlation of CSR and Consumer Behavior: A Study of Convenience StoreTrina GoswamiNessuna valutazione finora

- Consumer Behavior StylesDocumento14 pagineConsumer Behavior StylesMichelle LimNessuna valutazione finora

- Materialism and Its Associated ConceptsDocumento26 pagineMaterialism and Its Associated ConceptsGAYATHIRI MUNIANDYNessuna valutazione finora

- What We Know and Don't Know About Corporate Social Responsibility A Review and Research AgendaDocumento39 pagineWhat We Know and Don't Know About Corporate Social Responsibility A Review and Research AgendaAndra ComanNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Cues Effect on Customer Behavior Mediated by Emotions and CognitionDocumento12 pagineSocial Cues Effect on Customer Behavior Mediated by Emotions and CognitionhendraNessuna valutazione finora

- ContentServer With Cover Page v2Documento15 pagineContentServer With Cover Page v2Sonam GuptaNessuna valutazione finora

- Paradigm Shifts in Consumer Behavior Meta-AnalysisDocumento12 pagineParadigm Shifts in Consumer Behavior Meta-AnalysisjuansNessuna valutazione finora

- An Empirical Investigation of The Relationships Among A Consumer's Personal Values, Ethical Ideology and Ethical BeliefsDocumento19 pagineAn Empirical Investigation of The Relationships Among A Consumer's Personal Values, Ethical Ideology and Ethical BeliefsMomina AbbasiNessuna valutazione finora

- Comparing The Importance of Luxury Value Perceptions in Cross-National ContextsDocumento8 pagineComparing The Importance of Luxury Value Perceptions in Cross-National Contextsajn05Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sustainable Luxury Current Status and Perspectives For Future ResearchDocumento61 pagineSustainable Luxury Current Status and Perspectives For Future ResearchAngrboda SobNessuna valutazione finora

- Ethical Consumers Among The Millennials. A Cross-National StudyDocumento20 pagineEthical Consumers Among The Millennials. A Cross-National StudyfutulashNessuna valutazione finora

- Cross Cultural DifferencesDocumento32 pagineCross Cultural DifferencesKwan KaaNessuna valutazione finora

- Impact of Brand Credibility and Consumer Values On Consumer Purchase Intentions in PakistanDocumento10 pagineImpact of Brand Credibility and Consumer Values On Consumer Purchase Intentions in Pakistanمحمد اکرام الحقNessuna valutazione finora

- Consumer Identity Work As Moral Protagonism: How Myth and Ideology Animate A Brand-Mediated Moral ConflictDocumento17 pagineConsumer Identity Work As Moral Protagonism: How Myth and Ideology Animate A Brand-Mediated Moral Conflictmgiesler5229Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ahmadi Et Al., 2012Documento14 pagineAhmadi Et Al., 2012diana_vataman_1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Beyond Demographic Boundary: Determining Generational Values by CohortsDocumento10 pagineBeyond Demographic Boundary: Determining Generational Values by CohortsLee NicoNessuna valutazione finora

- FinalDocumento10 pagineFinalSabyasachi RoutNessuna valutazione finora

- CHAPTER 2 - ResearchDocumento7 pagineCHAPTER 2 - Researchdaniel terencioNessuna valutazione finora

- Cultural Dimensions of Mexican Footwear CompanyDocumento14 pagineCultural Dimensions of Mexican Footwear CompanyHarshraj ChavanNessuna valutazione finora

- 2020 Arielisagivroccas2Documento46 pagine2020 Arielisagivroccas2Ja LuoNessuna valutazione finora

- Fashion Marketing of Luxury BrandsDocumento4 pagineFashion Marketing of Luxury BrandsOlaru Sabina100% (1)

- Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services: Ajay Kumar, Justin Paul, Slađana Star Cevi CDocumento12 pagineJournal of Retailing and Consumer Services: Ajay Kumar, Justin Paul, Slađana Star Cevi CVarinder Pal SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Literature Review On CultureDocumento8 pagineLiterature Review On Culturexvszcorif100% (1)

- Cerpen Cinta Ahmad MutawakkilDocumento18 pagineCerpen Cinta Ahmad MutawakkilYang QammarinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Emerging Research Trends in Sustainable Development StudiesDocumento7 pagineEmerging Research Trends in Sustainable Development StudiesInternational Journal of Advance Study and Research WorkNessuna valutazione finora

- Consumers and Brands Across The Globe: Research Synthesis and New DirectionsDocumento22 pagineConsumers and Brands Across The Globe: Research Synthesis and New DirectionsHjasbslabhxdkNessuna valutazione finora

- 106 PDFDocumento10 pagine106 PDFlestat stephyNessuna valutazione finora

- A Conceptual Culture Model For Design Science Research: March 2016Documento20 pagineA Conceptual Culture Model For Design Science Research: March 2016arif munandarNessuna valutazione finora

- Literature Review For Organizational Culture and EnvironmentDocumento6 pagineLiterature Review For Organizational Culture and EnvironmentsgfdsvbndNessuna valutazione finora

- 2021 Carrington Article ConsumptionEthicsAReviewAndAnaDocumento24 pagine2021 Carrington Article ConsumptionEthicsAReviewAndAnaCarlosNessuna valutazione finora

- Drivers of Brand Commitment: A Cross-National Investigation: Andreas B. Eisingerich and Gaia RuberaDocumento16 pagineDrivers of Brand Commitment: A Cross-National Investigation: Andreas B. Eisingerich and Gaia RuberaFiaz MehmoodNessuna valutazione finora

- Impact of Marital Status On Purchase Behaviour of Luxury BrandsDocumento12 pagineImpact of Marital Status On Purchase Behaviour of Luxury BrandsIOSRjournalNessuna valutazione finora

- How Generations, Gender and Attitudes Impact Fashion SpendingDocumento10 pagineHow Generations, Gender and Attitudes Impact Fashion SpendingNil BilgenNessuna valutazione finora

- Cross-Cul Tural Dif Fer Ences in Con Sumer de Ci Sion-Mak Ing StylesDocumento31 pagineCross-Cul Tural Dif Fer Ences in Con Sumer de Ci Sion-Mak Ing Stylesann2020Nessuna valutazione finora

- Unethical BehaviourDocumento16 pagineUnethical BehaviourJoaoPinto100% (1)

- A Study of Clothing Purchasing Behavior by Gender With Respect To Fashion and Brand AwarenessDocumento15 pagineA Study of Clothing Purchasing Behavior by Gender With Respect To Fashion and Brand AwarenessJanah Beado PagayNessuna valutazione finora

- Consumer Behaviour in Luxury Shopping.Documento12 pagineConsumer Behaviour in Luxury Shopping.Manzil MadhwaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Cross-Cultural Perspectives on the Value of Luxury ConsumptionDocumento17 pagineCross-Cultural Perspectives on the Value of Luxury Consumptionuswah razakNessuna valutazione finora

- 1Documento31 pagine1Suhendra HidayatNessuna valutazione finora

- Hofstede Organization SudiesDocumento18 pagineHofstede Organization SudiesErtunc YesilozNessuna valutazione finora

- Consumer Behavior Towards PersDocumento25 pagineConsumer Behavior Towards PersAnurag PalNessuna valutazione finora

- Gökhan TekinDocumento24 pagineGökhan Tekinchinmay gandhiNessuna valutazione finora

- The Influence of Personality Types On The Impulsive Buying Behavior of A ConsumerDocumento9 pagineThe Influence of Personality Types On The Impulsive Buying Behavior of A ConsumerSilky GaurNessuna valutazione finora

- Corporate Social Responsibility at IKEADocumento39 pagineCorporate Social Responsibility at IKEASook Kuan YapNessuna valutazione finora

- Bib .Rakesh PuniaDocumento16 pagineBib .Rakesh Puniasarkiawalia84Nessuna valutazione finora