Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Market Valuation of Intangible Assets: Evidence from Matched Portfolio Analysis and Regression

Caricato da

Filip JuncuDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Market Valuation of Intangible Assets: Evidence from Matched Portfolio Analysis and Regression

Caricato da

Filip JuncuCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Market Valuation of Intangible Assets

Won W. Choi

DONGGUK UNIVERSITY

Sung S. Kwon

RUTGERS UNIVERSITYCAMDEN

Gerald J. Lobo

SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY

Whether information on intangible assets reported under current financial

reporting requirements conveys information that is relevant to market

participants valuation of firms equity has long been a question of interest

to accounting policymakers and researchers. This study provides empirical

evidence on the relationship between the reported value of intangible

assets, the associated amortization expense, and firms equity market

values. These relationships are examined using a matched pair portfolio

analysis and multiple regression analysis that has been used in prior

research on this topic. The results indicate that the financial market

positively values reported intangible assets. Furthermore, consistent with

theoretical predictions, the markets valuation of a dollar of intangible

assets is lower than its valuation of other reported assets. The results also

indicate that, although the market values amortization expense differently

from other expenses reported in the income statement, it does not negatively

value amortization expense. These results support the current requirement

that intangible assets be reported in firms balance sheets. However,

they do not support the current requirement that intangible assets be

periodically amortized to reflect the assumed decline in their value. J BUSN

RES 2000. 49.3545. 2000 Elsevier Science Inc. All rights reserved

his study examines the relationship between the reported value of intangible assets, the associated amortization expense, and firms equity market values. It is

motivated by the accounting for intangible assets required by

Accounting Principles Board (APB) Opinion No. 17, under

which firms must capitalize the cost of intangible assets and

amortize that cost over a period not to exceed 40 years or

the economic life of the asset, whichever is shorter. These

accounting requirements have long been the subject of controversy. At the core of the controversy is whether the reported

value of intangible assets on the balance sheet reflects the

Address correspondence to Gerald J. Lobo, School of Management, Syracuse

University, 900 S. Crouse Avenue, Syracuse, NY 13244.

Journal of Business Research 49, 3545 (2000)

2000 Elsevier Science Inc. All rights reserved

655 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10010

value of their future economic benefits. A related question is

whether recorded periodic amortization of intangible assets

reflects the decline in their economic value. This research

provides empirical evidence on the extent to which the reported value of intangible assets and its related amortization

expense are reflected in the market value of firms equity.

This evidence is important to users of financial statements for

decision making and to accounting regulators for making

financial reporting policy.

At a more general level, financial statements often have been

criticized for failing to reflect differences in the uncertainty of

future economic benefits and costs associated with different

assets. The balance sheet does not differentially weight assets

that differ in the levels of uncertainty associated with their

related future economic benefits and their related costs. In

addition, the income statement does not differentially weight

different revenue and expense items that have unequal degrees

of uncertainty. Most valuation models, however, indicate that

the value of an asset is inversely related to the uncertainty of

the associated future benefits expected from that asset (Robichek and Myers, 1966; Rubinstein, 1973; Epstein and Turnbull, 1980). This relationship between uncertainty and asset

value is ignored in most balance sheet and income statement

measures and is the primary reason for this criticism of financial statements. It is especially relevant to intangible assets

because of the significantly greater uncertainty associated with

the amount and timing of their future economic benefits.1

Egginton (1990) and Hodgson, Okunev, and Willett (1993)

indicated that flat rate amortization (e.g., straight-line amortization over 40 years) of a particular type of intangible asset

across all firms ignores potentially significant economic differ-

For example, Rabe and Reilly (1996), and Reilly (1996) reported that the

valuation of intangible assets has become an increasingly more integral and

more complex part of the current health care environment and the corporate

bankruptcy and reorganization environment, respectively.

ISSN 0148-2963/00/$see front matter

PII S0148-2963(98)00121-0

36

J Busn Res

2000:49:3545

ences, thereby resulting in the periodic decline in the value

of the intangible asset being reported in the income statement

with considerable error. The periodic consumption of an intangible asset depends on the nature of the asset, its economic

life, and the pattern of consumption of its future economic

benefits. Unlike tangible assets, there is considerably greater

uncertainty involved in determining lifetime duration during

which the assets economic benefit will be consumed and

the periodic reduction pattern of the assets service potential,

because it is unclear what the specific benefit is.2 This greater

degree of uncertainty results in a reduction in the accuracy

of the amortization of the intangible asset that is reported in

the income statement.

We provide empirical evidence that is relevant to the controversies and criticisms discussed above. We use a matched

portfolio approach to examine these issues in addition to using

the regression analysis approach that has been employed in

prior research. First, we examine whether firms equity market

values reflect reported values of intangible assets and their

associated amortization expense. To test the balance sheet

(income statement) valuation of intangible assets, we compare

book-to-market (earnings-to-market) values for a portfolio of

firms that have significant and stable amounts of intangible

assets (amortization expense) on their balance sheets (income

statements) to a matched portfolio of control firms that have

no intangible assets (amortization expense). The results of this

analysis provide evidence on the markets perception of the

value-relevance of the reported information on intangible

assets. Second, we examine whether the market valuation of

intangible assets and amortization expense differs from its

valuation of other balance sheet items and income statement

items, respectively. Consistent with the differential uncertainty

explanation, we test the hypothesis that the book-to-market

(earnings-to-market) value ratio of a portfolio of firms that

have significant and stable amounts of intangible assets and

include book values of such assets (amortization expense) on

their balance sheets (income statements) to a matched portfolio of control firms that report no intangible assets (amortization expense). The results of this analysis provide evidence

on the valuation implications of financial statements failure

to reflect differences in the levels of uncertainty across their

different elements. We also conduct tests by using regression

analysis to assess the robustness of our results and to provide

a basis for comparison of our results with those of prior

research.

Our portfolio tests indicate that firms equity market values

reflect reported values of intangible assets. However, no decline in market value is associated with reported amortization

expense. They also indicate that intangible assets and other

An intangible asset, such as goodwill, has no limited term of existence

and is not utilized or consumed in the earnings process. Consequently, its

amortization reduces the reliability of the income statement. (Johnson and

Tearney, 1993).

W. W. Choi et al.

balance sheet elements are not differentially valued. However,

we observe differences in the markets valuation of amortization expense and other income statement items. The results

of the regression analysis are consistent with the portfolio

results. They confirm the evidence of prior research concerning the value-relevance of reported intangible assets and the

price-irrelevance of the related amortization expense. These

results indicate that the market valuation does not reflect

significant differences in uncertainty between intangible assets

and other balance sheet elements. However, it does value

amortization expense related to intangible assets differently

from other income statement elements.

The rest of this article is organized as follows. Section 2

presents the background and identifies the issues addressed

in this article. Section 3 discusses the methodology and the

hypotheses examined. Section 4 describes the data collection

and portfolio formation. Section 5 presents the results of the

empirical analysis, and section 6 contains a summary and

conclusions of the study.

Background

Under APB Opinion No. 17 (American Institute of Certified

Public Accountants, 1970), intangible assets are accounted

for in a manner similar to the accounting required for property,

plant, and equipment. An intangible asset is recorded at historical cost and amortized over the period that the firm expects

to benefit from its use. However, unlike fixed assets, the

uncertainty in the degree and timing of future benefits expected from intangible assets is considerably greater. Because

of the higher levels of uncertainty associated with future benefits to be derived from intangible assets, many practitioners

and academics have suggested that such expenditures should

be written off in the period in which they are incurred. This

suggestion is consistent with valuation models, which indicate

that the value of an asset will approach zero as the level of

uncertainty of its future economic benefits approaches infinity.3 Whether the higher level of uncertainty associated with

the benefits from intangible assets is significant enough to

cause the market to discount those benefits more than it

does for other asset benefit streams is a question that can be

empirically investigated.

The continuing controversy surrounding the accounting

for intangible assets has drawn the attention of academic researchers. Much of the research has focused on issues related

to goodwill accounting, which is the largest intangible asset

3

The notion that the value of an asset will approach zero as the level of

uncertainty of its future economic benefits nears infinity is consistent with

the FASBs definition of an asset as a probable future economic benefit

controlled by an entity as a result of a past transaction or an event under

Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 3. In other words, if the

future realization of the economic benefits resulting from the use of the

intangible asset is not probable, then it should not be classified as an asset.

Market Valuation of Intangible Assets

for most firms.4 Studies by Amir, Harris, and Venuti (1993),

Chauvin and Hirschey (1994), and McCarthy and Schneider

(1995) reported a significant positive relationship between

goodwill and the market value of a firm. Jennings, Robinson,

Thompson, and Duvall (1996) empirically investigated the

relationship between market equity values and purchased goodwill. Consistent with earlier findings, their results indicate that

the market values purchased goodwill as an asset. However,

they find little evidence of a systematic relationship between

goodwill amortization and firms market values.

One explanation for the latter result of Jennings, Robinson,

Thompson, and Duvall (1996) is that goodwill amortization

measures required to be used under generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) do not correctly reflect the decline

in the economic value of the intangible asset during the period.

This results from the considerable amount of uncertainty associated with estimating the period over which the economic

benefit will be realized and the pattern of reduction of the

assets economic benefit. An alternative way of stating this

is that the high levels of uncertainty associated with future

economic benefits from intangible assets result in amortization

measures that contain large amounts of error. While errors

in measuring amortization expense also will affect the reported

asset value on the balance sheet, the effects of such errors will

not impact balance sheet measures as significantly as they do

income statement measures. There are two reasons for this.

First, the size of the error resulting from incorrectly measuring

amortization expense is relatively smaller for the reported

balance sheet asset than the reported income statement expense.5 Second, to the extent that errors in measuring amortization expense are not highly correlated over time, the cumulative error is likely to be smaller than any single periods error.

Therefore, a cross-sectional regression approach such as that

used by Jennings, Robinson, Thompson, and Duvall (1996)

is likely to show significant relationships between market

values and reported balance sheet goodwill assets but not

between market values and reported income statement goodwill amortization expense.

We test two hypotheses in this study. First, we examine

whether reported amounts for intangible assets and amortization expense are value relevant. If the market value of a firm

reflects reported values for intangible assets and amortization

expense, then we can infer that the market perceives the

information provided by APB No.17 to be value-relevant.

Jennings, Robinson, Thompson, and Duvall (1996) also tested

J Busn Res

2000:49:3545

37

this hypothesis by using the regression approach. Second, we

examine whether the market values reported intangible assets

and amortization expenses differently from other components

of the balance sheet and the income statement, respectively.

Evidence of differential valuation will support those who argue

that intangible assets should be treated differently from other

elements of the balance sheet and income statement. Alternatively, if we find no difference in the markets valuation of

these intangible asset measures, then our results will provide

support for the reporting requirements under APB Opinion

No. 17.

We employ two different approaches in this study. In addition to using cross-sectional regressions as in Jennings, Robinson, Thompson, and Duvall (1996) and others to confirm

the validity of our data in relation to these previous studies,

we also use a portfolio approach that is not as sensitive to

the measurement and econometric problems associated with

intangible assets. Additionally, unlike Jennings, Robinson,

Thompson, and Duvall (1996), we do not impose a linear

structure on the cross-sectional market value-intangible asset

relationship. This is important because the market value assigned to intangible assets is likely to differ across firms because of differential amounts of uncertainty associated with

their future economic benefits. We use a control portfolio as

a benchmark to compare the market values associated with

reported intangible assets and amortization expense. We also

use this portfolio approach to test whether the impact of

intangible assets and amortization expense on firms market

values differs from the impact of other line items in the balance

sheet and income statement, respectively.

Methodology and Hypotheses

Market Valuation of Reported Balance

Sheet Items

We form three portfolios to assess the markets valuation

of intangible assets reported in the balance sheet. The first

portfolio, labeled the experimental portfolio comprises firms

with significant amounts of intangible assets that have been

relatively stable over the past three years. This allows us to

focus on the markets valuation of intangible assets that have

been on the firms books for some length of time rather than

on recently acquired intangible assets.6 The second portfolio

comprises the same firms as the experimental portfolio. However, the book value of intangible assets has been subtracted

from each firms balance sheet. We label this the adjusted

McCarthy and Schneider (1995) reported that their research of the COMPUSTAT database identified 1,451 firms reporting goodwill in the aggregate

amount of $158 billion.

5

Consider an intangible asset costing $100, a life of 10 years, and annual

amortization expense of $10. This asset will be reported at $90 on the balance

sheet at the end of year one. If true amortization expense is $11, then the

error in amortization expense expressed as a percentage of the reported

amount is 10%. The true balance sheet amount is $89; therefore, the error

is approximately 1%.

The book value and market value of recently acquired intangible assets are

likely to be closer to one another because the book value will more closely

reflect the price at which the asset was acquired. Consequently, there will

be little impact of accounting methods on the reported book value of the

asset. By restricting the experimental firms to those that have had intangible

assets for a longer period, we are able to focus on how closely the accounting

for these assets corresponds to the markets assessment of their value.

38

J Busn Res

2000:49:3545

portfolio. The third portfolio comprises firms that do not

report any intangible assets. We label it the control portfolio.

Firms in the control portfolio are pairwise matched with the

adjusted firms based on three financial statement items: total

assets, book value of equity, and earnings.7 Additionally, firms

in each pair are matched in terms of industry and calendar year.

We compare book-to-market value (BM) ratios of control

and adjusted portfolios to test whether the market positively

values intangible assets. Ceteris paribus, if the market value

assigned to intangible assets is zero, then the BM ratios of the

control and adjusted portfolios will be equal. Alternatively, if

the market places a positive value on intangible assets, then

the BM ratio of the adjusted portfolio will be less than that

of the control portfolio. This is so because the market value

of the adjusted portfolio includes the market value assigned to

intangible assets, whereas its book value excludes the reported

intangible asset value. Consistent with the above reasoning,

we test the following hypothesis (stated in its alternate form):

HB1: The book-to-market value ratio of the adjusted portfolio is less than the book-to-market value ratio of

the control portfolio.

Our second hypothesis examines whether the BM ratio of

intangible assets differs from the BM ratio of tangible assets.

We compare BM ratios between the experimental and control

portfolios to test this hypothesis. If the market values each

dollar of intangible assets and tangible assets equally, then

the experimental and control portfolios will have equal BM

ratios. Alternatively, if the market valuation per dollar of intangible assets is lower than its valuation of tangible assets, then

the BM ratio of the experimental portfolio will exceed that

of the control portfolio. We formalize the above discussion

with the following hypothesis (stated in its alternate form):

HB2: The book-to-market value ratio of the experimental

portfolio is greater than the book-to-market value

ratio of the control portfolio.

Market Valuation of

Reported Income Statement Items

We use an analogous procedure to assess the markets valuation of amortization expense related to intangible assets reported in the income statement. Once again, we form three

portfolios. The first portfolio, labeled the experimental portfolio, comprises firms with significant amounts of amortization

expense that have been relatively stable over the past three

years. The second portfolio, labeled the adjusted portfolio,

These three variables allow us to control for size (by total assets), debt-toequity ratio (by book value of equity and total assets), and return-on-equity

(by earnings and book value of equity). Prior research has shown that these

variables are significant in explaining firms equity market values (e.g., Atiase,

1985; Lang, 1991).

W. W. Choi et al.

comprises the same firms as the experimental portfolio; however, the earnings are adjusted to remove the effect of deducting amortization expense related to intangible assets. This

results in the adjusted firms earnings always exceeding the

experimental firms earnings. The third portfolio contains

firms that do not report amortization expense. Firms in this

control portfolio are pairwise matched with the adjusted

firms based on total assets, book value of equity, earnings,

industry, and year.

We compare earnings-to-market value (EM) ratios between

control and adjusted portfolios to examine whether the market

reflects reported amortization expense in its valuation. Ceteris

paribus, if amortization expense has no effect on market value,

them the EM ratios of the control and adjusted portfolios will

be equal. Alternatively, if the market value declines as a result

of the reported amortization expense, then the EM ratio of

the adjusted portfolio will be greater than that of the control

portfolio. This is so because the negative effect of the amortization expense is reflected in the market value of the adjusted

portfolio but not in its earnings. Based upon the above discussion, we test the following hypothesis (stated in its alternate

form):

HI1: The earnings-to-market value ratio of the adjusted

portfolio is greater than the earnings-to-market value

ratio of the control portfolio.

Our second income statement-related hypothesis examines

whether the effect of each dollar of amortization expense on

market value differs from the corresponding effect of other

income statement elements. We compare EM ratios between

experimental and control portfolios to test this hypothesis. If

the market value decrease per dollar of amortization expense

equals the market value decrease per dollar of other income

statement elements, then the experimental and control portfolios will have equal EM ratios. Alternatively, if the reduction

in market value per dollar of amortization expense is less than

it is for other income statement components, then the EM

ratio for the experimental portfolio will be lower than the EM

ratio for the control portfolio. Consistent with this reasoning,

we test the following hypothesis (stated in its alternate form):

HI2: The earnings-to-market value ratio of the experimental portfolio is less than the earnings-to-market value

ratio of the control portfolio.

Data, Sample Selection,

and Portfolio Formation

The test period for our study extends from 1978 to 1994.

Sample firms are selected from among those with available

data in the 1995 COMPUSTAT Industrials Annual file and

the CRSP monthly returns file. We use the following threestep procedure to select firm-year observations for testing our

hypotheses:

Market Valuation of Intangible Assets

1. Selection of firms with significant amounts of intangible

assets (amortization expense) for testing the balance

sheet (income statement) hypotheses. Observations

comprising the experimental portfolios are selected

from among these firms.

2. Selection of firms with no intangible assets (amortization expense). These observations are used to form the

control portfolios.

3. Matching experimental and control observations. These

matched portfolios are used for testing the balance sheet

and income statement hypotheses.

Each of these steps is described in more detail in the remainder of this section.

Portfolio Formation for Balance Sheet Hypotheses

Experimental

firm-year observations are required to satisfy the following

criteria:

SELECTION OF EXPERIMENTAL OBSERVATIONS.

1. The ratio of intangible assets to total assets is greater

than 10%. This criterion ensures that the experimental

observations have significant amounts of intangible

assets. It enhances the power of our tests because we

compare these observations with observations that have

no intangible assets.

2. The ratio of intangible assets to total assets does not

vary by more than 50% over the three-year period ending with the test year. This criterion ensures that the

experimental observations have stable amounts of intangible assets for some length of time prior to the test

year (i.e., the major portion of intangible assets has not

been recently acquired).

3. Data is available on total assets, book value of equity,

and earnings. These variables are used to match experimental observations with control observations. Prior

research indicates that BM ratios (the dependent variable) are related to these three variables. By matching

observations along these three dimensions, we control

for differences in BM ratios that may result from differences in these variables.

4. These observations (for testing the balance sheet

hypotheses) do not overlap with those used for testing

the income statement hypotheses (which are discussed

later). By focusing on observations with significant balance sheet effects but insignificant income statement

effects, differences in BM ratios can more reliably be

attributed to differences in intangible assets reported

on the balance sheet.

These criteria result in a sample of 1,024 firm-year observations over the 17-year period 1978 to 1994. There were 219

different firms represented in the sample.

SELECTION OF CONTROL OBSERVATIONS. Our research design

compares firms with significant and stable amounts of intangi-

J Busn Res

2000:49:3545

39

ble assets to matched firms that have no intangible assets.

Control firms are required to:

1. Have no intangible assets and amortization expenses.

2. Have data available on total assets, book value of equity,

and earnings.

These criteria result in 14,683 firm-year observations that

are matched with the experimental observations for testing

both the balance sheet and income statement hypotheses.

MATCHING EXPERIMENTAL WITH CONTROL OBSERVATIONS. Before matching the experimental with the control observations,

we recalculate the total assets, book value of equity, and

earnings of the experimental firms after eliminating intangible

assets and amortization expenses. We reduce the book value

of equity by the amount of intangible assets removed from

the asset side of the balance sheet. Amortization expenses are

added back to earnings. Each adjusted firm-year observation

is then matched with a control firm-year observation by using

the following criteria:

1. The control and adjusted observations are from the

same year.

2. The control and adjusted firms belong to the same onedigit SIC industry.

3. The total assets, book value of equity, and earnings for

the control observation are each within 15% of the

corresponding measures for the adjusted observation.8

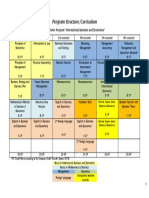

These matching criteria result in 83 matched pairs of adjusted and control firms. Panel A of Table 1 summarizes the

sample distribution by year and industry.

Portfolio Formation for

Income Statement Hypotheses

Experimental

observations are required to satisfy the following criteria:

SELECTION OF EXPERIMENTAL OBSERVATIONS.

1. The ratio of amortization expense to sales is greater

than 0.25%. This criterion ensures that the experimental

firms have significant amounts of amortization expense.9

2. The ratio of amortization expense to sales does not vary

We used various ranges (from 5 to 30%) to control for these three variables.

The wider the range, the less the control, while the narrower the range, the

fewer the number of matched observations. Given this trade-off, we chose

15%, because it provided a sufficient number of observations for conducting

our tests. When more than one control firm satisfied these criteria, we ranked

the deviations of total assets, book value of equity, and earnings between

control and adjusted observations, summed the ranks for each firm, and

selected the firm with the lowest total rank.

9

The choice of 0.25% is derived from criterion (1) for selecting experimental observations for the balance sheet tests (intangible assets must comprise

at least 10% of total assets) and the maximum amortization period for intangible assets of 40 years specified in APB No. 17. This cutoff provides a comparable sample size for the income statement tests to that used for the balance

sheet tests.

40

J Busn Res

2000:49:3545

W. W. Choi et al.

Table 1. Distribution of Sample Observations

Panel A: Sample Observations for Portfolio Tests of Balance Sheet

Hypotheses

Industrya

Year

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

Total

3

2

5

1

1

2

1

1

3

3

2

2

3

1

3

2

5

40

1

1

1

3

1

1

2

3

2

4

18

3

2

1

6

1

2

1

1

1

2

1

9

2

1

2

6

1

1

3

Total

4

3

5

2

1

2

3

1

3

5

10

2

6

4

10

8

14

83

Panel B: Sample Observations for Portfolio Tests of Income Statement

Hypotheses

Industrya

Year

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

Total

2

1

2

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

1

2

2

2

3

2

3

1

2

2

1

3

4

21

4

3

25

1

2

3

2

2

2

1

2

3

4

3

2

2

32

1

1

1

1

3

1

3

1

1

1

2

12

1

1

Total

4

3

3

2

2

5

7

6

8

4

6

10

6

5

5

14

10

100

One-digit SIC codes: 1; mining, oil and gas, and construction; 2; light manufacturingfood, textile, furniture, printing, and chemical; 3; heavy manufacturing

rubber, glass, metal, electric, and measuring instrument; 4; transportation, communication, and utilities; 5; wholesale and retail trading; 6; financebanking, brokers, insurance, real estate, and investment; 7; personal and business servicehotel, repair, motion

picture, and amusement.

by more than fifty% over the three-year period ending

with the test year. This criterion ensures that the experimental firms have stable amounts of amortization expense for some length of time (i.e., the amortization

expense does not primarily result from recently acquired

intangible assets).

3. Data is available on total assets, book value of equity,

and earnings.

4. These observations (for testing the income statement

hypotheses) do not overlap with those used for testing

the balance sheet hypotheses (which were discussed

earlier). By focusing on observations with significant

income statement effects but insignificant balance sheet

effects, we can more reliably attribute differences in EM

ratios to differences in amortization expenses reported

on the income statement.These criteria result in a sample of 755 firm-year observations over the 17-year test

period. There were 241 different firms represented in

the sample.

The same 14,683

firm-year observations described in the balance sheet control

portfolio selection are used.

SELECTION OF CONTROL OBSERVATIONS.

Matching Experimental

with Control Observations

The same adjustments and matching criteria used for the

balance sheet portfolio are employed. These criteria result in

100 matched pairs of adjusted and control observations. Panel

B of Table 1 summarizes the sample distribution by year and

industry.

Empirical Results

We first present the results of the portfolio analyses. These

results are reported in Tables 2 through 5. We compare mean

(panel A) and median (panel B) values of BM ratios and EM

ratios for the experimental, adjusted, and control portfolios.

Tables 2 and 4 present the analyses for portfolios with matched

observations that are within 15% in terms of the three

control variables (total assets, book value of equity, and earnings. To provide an indication of the sensitivity of our results

to the choice of the 15% matching criterion, we report

corresponding results for observations matched on a 10%

criterion in Tables 3 and 5. The portfolio results are followed

by regression analysis results in Table 6. These results serve

as a basis for comparison with prior research and for comparison with the results of the matched portfolio analysis.

Results of Matched Portfolio Analysis

We first present the results of tests of the balance sheet hypotheses. These are followed by test results for the income statement hypotheses.

TESTS OF BALANCE SHEET HYPOTHESES. Consistent with the

sample selection criteria, the experimental firms exhibit significant amounts of intangible assets as shown in Table 2. The

mean (median) proportion of intangible assets to total assets

is 15.78% (18.32%). The results reported in panel A also

provide evidence on the efficacy of the matching procedure.

There is little difference between mean (and median) values

Market Valuation of Intangible Assets

J Busn Res

2000:49:3545

41

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics of Variables for Experimental, Adjusted and Control Samples for Tests of Balance Sheet Hypotheses

Panel A: Analysis of Mean Values

Mean Value

Variables

PIA

PAE

TA

BE

EBX

BM

p-Value from Paired t-Test

Experimental

Portfolio

Adjusted

Portfolio

Control

Portfolio

ExperimentalControl pairs

AdjustedControl pairs

0.1578

0.0017

831

396

51.00

0.6295

705

269

52.26

0.4522

695

275

52.07

0.6195

0.0000

0.0000

0.2399

0.3774

0.1406

0.2875

0.4909

0.0000

Panel B: Analysis of Median Values

Median Value

Variables

PIA

PAE

TA

BE

EBX

BM

p-Value from Signed-Ranks Test

Experimental

Portfolio

Adjusted

Portfolio

Control

Portfolio

ExperimentalControl pairs

AdjustedControl pairs

0.1832

0.0000

319

184

17.16

0.5571

225

122

17.16

0.3965

230

114

16.23

0.5589

0.0000

0.0000

0.3816

0.7966

0.1398

0.3013

0.4653

0.0000

83 matched pairs, control variables are within 15%.

Variable definitions: PIA, proportion of reported intangible assets (IA) to total assets (TA); PAE, proportion of amortization expense (AE) to sales; TA, total assets; BE, book value

of common equity; EBX, earnings before extraordinary items; BM, book-to-market value ratio BE/market value of common equity.

of total assets, book value of equity, and earnings across the

adjusted and control portfolios. This suggests that it is unlikely

that observed differences in BM ratios result from differences

in these control variables. We compare BM ratios for the

adjusted and control portfolios to test hypothesis HB1. Both

the mean and median BM ratios for the adjusted firms are

less than their corresponding values for the control firms.

The parametric paired t-test and the nonparametric Wilcoxon

matched-pairs signed-ranks test indicate that the differences

in BM ratios are significant at the 0.01 level. These results

indicate that the market positively values intangible assets.

To test the second balance sheet hypothesis, we compare

BM ratios between the experimental and control firms. Consistent with the hypothesis, both the mean and median BM

ratios for the experimental portfolio are greater than their

corresponding values for the control portfolio. However, the

differences are not statistically significant. Based on these results, we are unable to reject the null hypothesis that the

market differentially values intangible and tangible assets.

To examine the sensitivity of these results to the matching

criterion of 15% that was used for the control variables, we

repeat the tests by using portfolios that are matched using

a 10% criterion. This stricter criterion enables us to better

match the experimental, adjusted, and control portfolios;

however, it results in a smaller number of matched pairs.

Thus, while the power of our tests increases because of the

better matching, it is reduced by the smaller number of available observations. The results reported in Table 3 are consis-

tent with those reported in Table 2. They suggest that the

earlier conclusions are relatively insensitive to our choice of

matching criteria.

Sample statistics

for testing the two income statement hypotheses are reported

in Table 4. Consistent with the selection criteria, the experimental firms exhibit significant amounts of amortization expense. The adjusted and control portfolios appear well

matched in terms of the control variables. Parametric and

nonparametric tests indicate that there are insignificant differences in total assets, book value of equity, and earnings across

these portfolios. Therefore, it is unlikely that observed differences in EM ratios across these portfolios are attributable to

differences in these control variables.

Hypothesis HI1 indicates that the adjusted portfolio will

have a larger EM ratio than the EM ratio for the control

portfolio. The results reported in panel B show that neither

the mean nor the median EM ratio for the adjusted firms is

greater than its corresponding value for the control firms.

Based on this result, we are unable to reject the hypothesis

that reported amortization expense related to intangible assets

is reflected in firms equity market values. We compare EM

ratios for the experimental and control portfolios to test the

second income statement hypothesis. As predicted, the mean

and median EM ratios for the experimental portfolio are each

significantly lower than their corresponding values for the

control firms. Based on these results, we conclude that the

TESTS OF INCOME STATEMENT HYPOTHESES.

42

J Busn Res

2000:49:3545

W. W. Choi et al.

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics of Variables for Experimental, Adjusted and Control Samples for the Tests of Balance Sheet Hypotheses

Panel A: Analysis of Mean Values

Mean Value

Variables

PIA

PAE

TA

BE

EBX

BM

p-Value from Paired t-Test

Experimental

Portfolio

Adjusted

Portfolio

Control

Portfolio

ExperimentalControl pairs

AdjustedControl pairs

0.1478

0.0018

640

310

39.43

0.6947

543

214

40.62

0.5031

542

216

40.24

0.6610

0.0000

0.0000

0.0420

0.3176

0.9399

0.9212

0.9139

0.0046

Panel B: Analysis of Median Values

Median Value

Variables

PIA

PAE

TA

BE

EBX

BM

p-Value from Signed-Ranks Test

Experimental

Portfolio

Adjusted

Portfolio

Control

Portfolio

ExperimentalControl Pairs

AdjustedControl Pairs

0.1373

0.0000

289

153

16.06

0.5894

247

86

16.06

0.4456

248

81

15.96

0.6224

0.0000

0.0000

0.0510

0.6893

0.8123

0.8838

0.8694

0.0059

32 matched pairs, control variables are within 10%.

Variable definitions: PIA, proportion of reported intangible assets (IA) to total assets (TA); PAE, proportion of amortization expense (AE) to sales; TA, total assets; BE, book value

of common equity; EBX, earnings before extraordinary items; BM, book-to-market value ratio BE/market value of common equity.

Table 4. Descriptive Statistics of Variables for Experimental, Adjusted and Control Samples for Tests of Income Statement Hypotheses

Panel A: Analysis of Mean Values

Mean Value

Variables

PIA

PAE

TA

BE

EBX

EM

p-Value from Paired t-Test

Experimental

Portfolio

Adjusted

Portfolio

Control

Portfolio

ExperimentalControl pairs

AdjustedControl pairs

0.0641

0.0066

1547

609

73.48

0.0733

1467

529

80.59

0.0806

1462

530

79.08

0.0870

0.0000

0.0000

0.0008

0.0364

0.2680

0.5213

0.3227

0.8019

Panel B: Analysis of Median Values

Median Value

Variables

PIA

PAE

TA

BE

EBX

EM

p-Value from Signed-Ranks Test

Experimental

Portfolio

Adjusted

Portfolio

Control

Portfolio

ExperimentalControl pairs

AdjustedControl Pairs

0.0562

0.0043

446

212

25.13

0.0713

399

175

28.66

0.0762

397

172

26.42

0.0776

0.0000

0.0000

0.0000

0.0032

0.4159

0.6695

0.3194

0.8377

100 matched pairs, control variables are within 15%.

Variable definitions: PIA, proportion of reported intangible assets (IA) to total assets (TA); PAE, proportion of amortization expense (AE) to sales; TA, total assets; BE, book value

of common equity; EBX, earnings before extraordinary items; EM, earnings-to-market value ratio EBX/market value of common equity.

Market Valuation of Intangible Assets

J Busn Res

2000:49:3545

43

Table 5. Descriptive Statistics of Variables for Experimental, Adjusted and Control Samples for the Tests of Income Statement Hypotheses

Panel A: Analysis of Mean Values

Mean Value

Variables

PIA

PAE

TA

BE

EBX

EM

p-Value from Paired t-Test

Experimental

Portfolio

Adjusted

Portfolio

Control

Portfolio

ExperimentalControl pairs

AdjustedControl pairs

0.0928

0.0067

2253

911

117.55

0.0723

2119

776

126.52

0.0783

2165

805

126.45

0.0984

0.0007

0.0000

0.0998

0.0145

0.5464

0.4218

0.9686

0.9559

Panel B: Analysis of Median Values

Median Value

Variables

PIA

PAE

TA

BE

EBX

EM

p-Value from Signed-Ranks Test

Experimental

Portfolio

Adjusted

Portfolio

Control

Portfolio

ExperimentalControl Pairs

AdjustedControl Pairs

0.0597

0.0049

554

303

35.29

0.0744

522

184

38.11

0.0801

487

176

37.45

0.0776

0.0002

0.0000

0.0001

0.0214

0.5130

0.6368

0.8489

0.2070

30 matched pairs, control variables are within 10%.

Variable definitions: PIA, proportion of reported intangible assets (IA) to total assets (TA); PAE, proportion of amortization expense (AE) to sales; TA, total assets; BE, book value

of common equity; EBX, earnings before extraordinary items; EM, book-to-market value ratio EBX/market value of common equity.

market differentially values amortization expense and other

income statement items.

Table 5 reports results for matched portfolios based on the

stricter matching criterion of 10%. The results are consistent

with the results reported in Table 4. They indicate that, while

the market differentially values amortization expense and

other income statement items, we are unable to detect the

hypothesized negative effect of amortization expense.

Results of Regression Analyses

We first estimate the market value associated with reported

intangible assets. We then examine the impact of reported

amortization expense on firms market values.

TESTS OF BALANCE SHEET HYPOTHESES. We estimate the following regression model to estimate the relation between reported intangible assets and market value [Eq. (1)]:

MVit 0 1ABPIit 2PPEit

(1)

3IAit 4LIABit et

where MV market value of common equity measured at

the fiscal year end, ABPI book value of total assets minus

property, plant, and equipment and intangible assets, PPE

book value of property, plant, and equipment, IA book

value of intangible assets, and LIAB book value of sum of

liabilities plus book value of preferred stock.

Each of the above variables is scaled by the beginning-ofyear book value of total assets to reduce potential problems

resulting from heteroskedasticity. Model 1 is estimated using

1,024 firm-year observations with available data over the period of study.

The results of estimating model 1 are reported in panel A

of Table 6. They indicate that there is a strong relation between

market values of equity and reported book values of assets

and liabilities, which explain more than 50% of the variation

in market values. The coefficients on the asset variables, 1,

2, and 3, are all significantly greater than zero while the

coefficient on the liabilities variable is significantly negative.

The significant positive value for 3 is consistent with the

market positively valuing intangible assets. This result is consistent with Jennings, Robinson, Thompson, and Duvall

(1996) and McCarthy and Schneider (1995). Consistent with

our hypothesis, our results also show that the coefficient on

IA is less than the coefficients on PPE and ABPI. That 3 is

less than 2 and 1 suggests that the market views the future

benefits associated with IA to be more uncertain than the

future benefits associated with PPE or ABPI. This result differs

from Jennings, Robinson, Thompson, and Duvall (1996) and

McCarthy and Schneider (1995) who report higher valuations

for IA than for PPE and ABPI. One explanation for this difference is that, unlike those studies, our sample is structured to

include firms that have stable intangible assets.10

10

We also estimated model (1) on a year-by-year basis. Inferences from these

estimations are qualitatively similar to those reported in this section.

44

J Busn Res

2000:49:3545

W. W. Choi et al.

Table 6. Results of Regression Analysis

Panel A: Tests of Balance Sheet Hypotheses

Model: MVit b0 b1ABPIit b2PPEit b3IAit b4LIABit et

Coefficient

Estimate

White t

Prob |t|

0

1

2

3

4

1.5629

3.9520

4.5911

3.3326

2.7492

8.6924

12.5049

11.7155

4.2168

9.4544

0.0001

0.0001

0.0001

0.0001

0.0001

Adjusted R2

F-value

N

0.5131

270.25

1024

Panel B: Tests of Income Statement Hypotheses

Model: RETit c0 c1EBDAit c2DEPRit c3AMORit

c4MRETt et

Coefficient

Estimate

White t

Prob |t|

c0

c1

c2

c3

c4

0.0729

1.3053

0.9098

0.8651

0.7176

2.5806

7.4767

2.7507

0.9048

8.5458

0.0100

0.0001

0.0060

0.6342

0.0001

Adjusted R2

F-value

N

0.2438

58.63

755

Variable definitions: RET, annual stock return; EBDA, earnings before extraordinary

items plus depreciation and amortization expenses; DEPR, depreciation expenses of

property, plant, and equipment; AMOR, amortization expenses of intangible assets;

MRET, equally weighted market return adjusted for dividends payout (EBDA, DEPR,

and AMOR are deflated by beginning market value of comon equity.)

We estimate the

following regression model to estimate the relation between

reported amortization expense and market value [Eq. (2)]:

TESTS OF INCOME STATEMENT HYPOTHESES.

RETit 0 1EBDAit 2DEPRit

(2)

3AMORit 4MRETt et

where RET annual stock return over the fiscal year, EBDA

earnings before extraordinary items plus depreciation and

amortization expense, DEPR depreciation expense on property, plant, and equipment, AMOR amortization expense

on intangible assets, and MRET equally weighted market

return adjusted for dividend payout.

EBDA, DEPR, and AMOR are deflated by beginning of year

market value of common equity. Model 2 is estimated using

755 firm-year observations with available data over the period

of study.

The results of estimating model 2 are reported in panel B

of Table 6. They indicate that the income statement variables,

EBDA is significantly positively related to firm return and

DEPR is significantly negatively related to firm return. These

results are consistent with theoretical predictions. The market

positively values EBDA and negatively values DEPR. The re-

sults also indicate that the coefficient on amortization expense,

3, is not significantly related to firm return. This result is

consistent with Jennings, Robinson, Thompson, and Duvall

(1996), who also find that amortization expense is not significantly valued by the market. A probable explanation for this

result is that the measure of amortization expense used in

financial reports measures the decline in the value of intangible

assets with considerable error. The economic value of intangible assets may decline for some firms but increase for others.

However, APB Opinion No. 17 requires that intangible assets

be amortized regardless of whether their economic value increases or decreases with the passage of time. This treatment

could result in significant measurement error, which may

explain the insignificant relation between amortization expense and firm returns observed for our sample firms.

Summary and Conclusions

Financial reporting of intangible assets has long been a source

of controversy. Whether reporting of intangible assets and

their related amortization expense provides information that

is relevant to market participants valuation of firms equity

has been a question of continuing debate among accounting

policymakers and academics. This study provides empirical

evidence on the major issues of that debate.

The empirical results based on portfolio analyses indicate

that the financial market positively values reported intangible

assets on the balance sheet but insignificantly regards their

amortization expenses on the income statement. The markets

valuation of a dollar of intangible assets is, however, not

significantly different from its valuation of other reported balance sheet elements. Therefore, the portfolio tests fail to distinguish intangibles from other balance sheet assets according

to the degree and timing of uncertainty in the realization of

future benefits. Our results also suggest that, although the

market does not significantly value amortization expense, it

differentially values amortization expense related to intangible

assets and other income statement elements. These results are

further supported by regression analyses, which indicate that

there is a positive relation between the book value of intangible

assets and the market value of common equity. Moreover,

consistent with the uncertainty hypothesis, the markets valuation of a dollar of intangible assets is lower than its valuation

of other reported balance sheet items. With regards to the

income statement hypotheses, the regression analyses show

that amortization expense is not significantly related to annual

stock returns. These findings are consistent with those of the

portfolio analyses. They suggest that either the market does

not view intangible assets as wasting assets or that recorded

amortization expense reflects the decline in value of the intangible asset with considerable error.

The results of our study have several important implications. First, that intangible assets are positively valued by the

financial market supports the current GAAP requirement that

Market Valuation of Intangible Assets

these assets be reported on firms balance sheets rather than

being immediately expensed. Second, that amortization expense is not significantly related to stock returns does not

support the current GAAP requirement that reported income

be reduced by the periodic amortization of intangible assets.

The results of this study suggest that the current GAAP requirement of periodic amortization of intangible assets be seriously

questioned. One suggestion is that amortization expense be

based on assessed uncertainty in the degree and timing of

future benefits expected from each intangible asset. Finally,

that the market value per dollar of intangible assets is less

than the market value per dollar of tangible assets, and that

the market value associated with each dollar of amortization

expense is lower than the market value associated with each

dollar of other income statement items, is consistent with

relatively greater levels of uncertainty related to intangible

assets and amortization expense. These results support the

criticism of financial statements failure to reflect differential

levels of uncertainty across their different elements. They suggest that accounting reports would be more informative to

decision makers if they include information on differences in

uncertainty related to future economic benefits (costs) across

their different elements.

We thank John Wild, Douglas Schneider, and the anonymous reviewer for

valuable comments. Won Choi acknowledges financial support from Dongguk

University, Sung Kwon from the School of Business at Rutgers University,

and Gerald Lobo from the George E. Bennett Research Center and the Office

of the Vice President of Research and Computing at Syracuse University.

References

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, Accounting Principle Board. 1970. APB Opinion No.17Intangible Assets. New

York, NY: AICPA.

Amir, A., Harris, T. S., and Venuti, E. K.: A Comparison of the

J Busn Res

2000:49:3545

45

Value-Relevance of US versus Non-US GAAP Accounting Measures Using Form 20-F Reconciliations. Journal of Accounting Research 31 (1993): 230264.

Atiase, R. K.: Predisclosure Information, Firm Capitalization, and

Security Price Behavior around Earnings Announcements. Journal

of Accounting Research (1985): 2135.

Chauvin, K. W., and Hirschey, M.: Goodwill, Profitability, and the

Market Value of the Firm. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy

13 (1994): 159180.

Egginton, D.: Towards Some Principles for Intangible Asset Accounting. Accounting and Business Research 20 (1990): 193205.

Epstein, L. G., and Turnbull, S. M.: Capital Asset Prices and the

Temporal Resolution of Uncertainty. Journal of Finance 35 (June

1980): 627643.

Hodgson, A., Okunev, J., and Willett, R.: Accounting for Intangibles:

A Theoretical Perspective. Accounting and Business Research 23

(1993): 138150.

Jennings, R., Robinson, J., Thompson II, R. B., and Duvall, L.: The

Relation between Accounting Goodwill Numbers and Equity Values. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting 23 (1996): 513

533.

Johnson, J. D., and Tearney, M. G.: GoodwillAn Eternal Controversy. The CPA Journal 53 (April 1993): 5862.

Lang, M.: Time-Varying Stock Price Response to Earnings Induced

by Uncertainty about the Time Series Process of Earnings. Journal

of Accounting Research 29 (Autumn 1991): 229257.

McCarthy, M. G., and Schneider, D. K.: Market Perception of Goodwill: Some Empirical Evidence. Accounting and Business Research

26 (1995): 6981.

Rabe, J. G., and Reilly, R. F.: Valuing Health Care Intangible Assets.

National Public Accountant 41 (March 1996): 1443.

Reilly, R. F.: The Valuation of Intangible Assets. National Public

Accountant 41 (July 1996): 2640.

Robichek, A. A., and Myers, S. C.: Valuation of the Firm: Effects of

Uncertainty in a Market Context. Journal of Finance 21 (June

1966): 215227.

Rubinstein, M. E.: A Mean-Variance Synthesis of Corporate Financial

Theory. Journal of Finance 28 (March 1973): 167181.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Analyzing the Fair Market Value of Assets and the Stakeholders' Investment DecisionsDa EverandAnalyzing the Fair Market Value of Assets and the Stakeholders' Investment DecisionsNessuna valutazione finora

- Equity Investment IntangiblesDocumento51 pagineEquity Investment Intangiblesgj409gj548jNessuna valutazione finora

- Financial Performance Measures and Value Creation: the State of the ArtDa EverandFinancial Performance Measures and Value Creation: the State of the ArtNessuna valutazione finora

- Corporate Life Cycles Impact Cash Flow and Accrual RelevanceDocumento34 pagineCorporate Life Cycles Impact Cash Flow and Accrual Relevancedharmas13Nessuna valutazione finora

- What determines residual incomeDocumento44 pagineWhat determines residual incomeandiniaprilianiputri84Nessuna valutazione finora

- Value Relevance of Operating Income vs. Below-the-Line Items in ChinaDocumento26 pagineValue Relevance of Operating Income vs. Below-the-Line Items in ChinaSyiera Fella'sNessuna valutazione finora

- Evidence that Accounting Conservatism Exists and Has IncreasedDocumento36 pagineEvidence that Accounting Conservatism Exists and Has IncreasedcistoloNessuna valutazione finora

- Litreature ReviewDocumento3 pagineLitreature ReviewAditi SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Measuring and Valuing Intangible AssetsDocumento52 pagineMeasuring and Valuing Intangible AssetsFilip Juncu100% (1)

- Implications of Impairment Decisions and Assets’ Cash-Flow Horizons for Conservatism ResearchDocumento49 pagineImplications of Impairment Decisions and Assets’ Cash-Flow Horizons for Conservatism ResearchBhuwanNessuna valutazione finora

- Active Passive Appreciation ArticleDocumento7 pagineActive Passive Appreciation ArticleaabbotNessuna valutazione finora

- Wiley, Accounting Research Center, Booth School of Business, University of Chicago Journal of Accounting ResearchDocumento12 pagineWiley, Accounting Research Center, Booth School of Business, University of Chicago Journal of Accounting ResearchSafira DhyantiNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study - 1Documento5 pagineCase Study - 1Jordan BimandamaNessuna valutazione finora

- Auditor Going-Concern Opinion Shifts Market ValuationDocumento26 pagineAuditor Going-Concern Opinion Shifts Market Valuationdchristensen5Nessuna valutazione finora

- Fair Value Accounting For FinancialDocumento4 pagineFair Value Accounting For FinancialAashie SkystNessuna valutazione finora

- Capital Markets Research in Accounting 2020-2Documento13 pagineCapital Markets Research in Accounting 2020-2muhammadnoor zainuddinNessuna valutazione finora

- Do stealth restatements convey material information?Documento18 pagineDo stealth restatements convey material information?JeyNessuna valutazione finora

- The Contagion Effects of Accounting Restatements: Cristi A. GleasonDocumento28 pagineThe Contagion Effects of Accounting Restatements: Cristi A. GleasonEdiSukarmantoNessuna valutazione finora

- Accounting TheoryDocumento14 pagineAccounting TheoryDedew VonandaNessuna valutazione finora

- Intermediate Accounting I: Group TaskDocumento9 pagineIntermediate Accounting I: Group TaskxaraprotocolNessuna valutazione finora

- Research Paper 1Documento4 pagineResearch Paper 1kejsi bylykuNessuna valutazione finora

- 1255-Article Text-3796-1-10-20130709Documento6 pagine1255-Article Text-3796-1-10-20130709AbdullahNessuna valutazione finora

- Penman and Yehuda, 2004, The Pricing of Earnings and Cash FlowsDocumento50 paginePenman and Yehuda, 2004, The Pricing of Earnings and Cash FlowsAbdul KaderNessuna valutazione finora

- Accounting Conservatism, Financial Reporting and Stock ReturnsDocumento21 pagineAccounting Conservatism, Financial Reporting and Stock ReturnsChosy FangohoiNessuna valutazione finora

- Financial Statement AnalysisDocumento15 pagineFinancial Statement AnalysisachalaNessuna valutazione finora

- Usefulness of AccountingDocumento17 pagineUsefulness of AccountingMochamadMaarifNessuna valutazione finora

- Kelompok 2 PDFDocumento52 pagineKelompok 2 PDFIrvan Sii CoffeeNessuna valutazione finora

- 11AS04-091-Core CFO PredictionDocumento41 pagine11AS04-091-Core CFO Predictionmunir_18766927Nessuna valutazione finora

- Do Analysts and Auditors Use Information in Accruals?: Journal of Accounting Research Vol. 39 No. 1 June 2001Documento30 pagineDo Analysts and Auditors Use Information in Accruals?: Journal of Accounting Research Vol. 39 No. 1 June 2001Febiola YuliNessuna valutazione finora

- Corporate ReportingDocumento5 pagineCorporate ReportingRishit RawatNessuna valutazione finora

- Balance Sheet Growth and The Predictability of Stock ReturnsDocumento51 pagineBalance Sheet Growth and The Predictability of Stock Returnsdarwin_huaNessuna valutazione finora

- Empirical Evidence of The Role of Accoun 86f1ee80Documento14 pagineEmpirical Evidence of The Role of Accoun 86f1ee80LauraNessuna valutazione finora

- IAS 38 EssayDocumento9 pagineIAS 38 EssayZeryab100% (1)

- Unearned Revenue Liability and Firm ValueDocumento33 pagineUnearned Revenue Liability and Firm Valuethịnh hưngNessuna valutazione finora

- Earning and Equity ValuationDocumento30 pagineEarning and Equity ValuationdegenoidNessuna valutazione finora

- Retrieve (5) - Political ScienceDocumento25 pagineRetrieve (5) - Political ScienceUbaid FarooquiNessuna valutazione finora

- Understand Earnings QualityDocumento175 pagineUnderstand Earnings QualityVu LichNessuna valutazione finora

- SSRN Id1394639Documento21 pagineSSRN Id1394639nardmulatNessuna valutazione finora

- Financial Performance Impact on Stock PricesDocumento14 pagineFinancial Performance Impact on Stock PricesMuhammad Yasir YaqoobNessuna valutazione finora

- Can Asset Revaluation Manipulate Financials? A Case StudyDocumento12 pagineCan Asset Revaluation Manipulate Financials? A Case Studyaryogo restu kuncoroNessuna valutazione finora

- Financial Ratios Classification Impact of Cash Flow MeasurementDocumento11 pagineFinancial Ratios Classification Impact of Cash Flow MeasurementAnonymous O69Uk7Nessuna valutazione finora

- 2016 Arkan Roa Der PerDocumento14 pagine2016 Arkan Roa Der PerBunga DarajatNessuna valutazione finora

- Fair Value Disclosure, External Appraisers, and The Reliability of Fair Value MeasurementsDocumento16 pagineFair Value Disclosure, External Appraisers, and The Reliability of Fair Value MeasurementsRe ZhaNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter - 2 Review of LiteratureDocumento39 pagineChapter - 2 Review of LiteratureMannuNessuna valutazione finora

- Investor Reactions To Disclosures of Material Internal Control WeaknessesDocumento10 pagineInvestor Reactions To Disclosures of Material Internal Control WeaknessesAbeerAlgebaliNessuna valutazione finora

- Intangible Assets: Measurement, Drivers, UsefulnessDocumento33 pagineIntangible Assets: Measurement, Drivers, UsefulnessLaarnie PantinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Earnings and Cash Flow Performances Surrounding IpoDocumento20 pagineEarnings and Cash Flow Performances Surrounding IpoRizki AmeliaNessuna valutazione finora

- Do (Audit Firm and Key Audit Partner) Rotations Affect Value Relevance? Empirical Evidence From The Italian ContextDocumento10 pagineDo (Audit Firm and Key Audit Partner) Rotations Affect Value Relevance? Empirical Evidence From The Italian ContextNguyen Quang PhuongNessuna valutazione finora

- Accounting For Intangible Assets: Suggested Solutions: Accounting and Business ResearchDocumento31 pagineAccounting For Intangible Assets: Suggested Solutions: Accounting and Business ResearchAdanechNessuna valutazione finora

- Fair Value Accounting PDFDocumento8 pagineFair Value Accounting PDFbgq2296Nessuna valutazione finora

- This Is WhatDocumento14 pagineThis Is Whatnila illaNessuna valutazione finora

- Accounting Disclosures, Accounting Quality and Conditional and Unconditional ConservatismDocumento39 pagineAccounting Disclosures, Accounting Quality and Conditional and Unconditional ConservatismNaglikar NagarajNessuna valutazione finora

- FASB Fair Value Exposure Draft InsightsDocumento13 pagineFASB Fair Value Exposure Draft InsightsHonoré DéoulaNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study Ratio AnalysisDocumento6 pagineCase Study Ratio Analysisash867240% (1)

- 2 Debreceny XBRL Ratios 20101213Documento31 pagine2 Debreceny XBRL Ratios 20101213Ardi PrawiroNessuna valutazione finora

- Capital Structure - UltratechDocumento6 pagineCapital Structure - UltratechmubeenNessuna valutazione finora

- 10 - Tema3 - Lafond - Watts - 2008 - 45pDocumento59 pagine10 - Tema3 - Lafond - Watts - 2008 - 45pCristiane TiemiNessuna valutazione finora

- ValueDocumento9 pagineValueDivine ugboduNessuna valutazione finora

- The IPO Derby: Are There Consistent Losers and Winners On This Track?Documento36 pagineThe IPO Derby: Are There Consistent Losers and Winners On This Track?phuongthao241Nessuna valutazione finora

- Value Relevance of Book Value, Retained Earnings and Dividends: Premium vs. Discount FirmsDocumento38 pagineValue Relevance of Book Value, Retained Earnings and Dividends: Premium vs. Discount FirmsSumayya ChughtaiNessuna valutazione finora

- OVGU IBE Program StructureDocumento1 paginaOVGU IBE Program StructureFilip JuncuNessuna valutazione finora

- OVGU IBE Program HandbookDocumento52 pagineOVGU IBE Program HandbookFilip JuncuNessuna valutazione finora

- SSRN Id788927 PDFDocumento6 pagineSSRN Id788927 PDFAmanda PadillaNessuna valutazione finora

- Measuring and Valuing Intangible AssetsDocumento52 pagineMeasuring and Valuing Intangible AssetsFilip Juncu100% (1)

- Measuring the impact of intangible capital investments on productivity and economic growthDocumento6 pagineMeasuring the impact of intangible capital investments on productivity and economic growthFilip JuncuNessuna valutazione finora

- Chatzkel (2002)Documento25 pagineChatzkel (2002)Filip JuncuNessuna valutazione finora

- Pike & Roos (2000) IC Measurement and HVADocumento16 paginePike & Roos (2000) IC Measurement and HVAFilip JuncuNessuna valutazione finora

- IFRS (2013) IFRS Foundation ConstitutionDocumento19 pagineIFRS (2013) IFRS Foundation ConstitutionFilip JuncuNessuna valutazione finora

- IBE Description - OVGUDocumento47 pagineIBE Description - OVGUFilip JuncuNessuna valutazione finora

- Data BaseDocumento25 pagineData BaseFilip JuncuNessuna valutazione finora

- AvP - 2011 01 20 - 16 07 02Documento1 paginaAvP - 2011 01 20 - 16 07 02Filip JuncuNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To Corporate FinanceDocumento26 pagineIntroduction To Corporate Financekristina niaNessuna valutazione finora

- Batangas State University Exam Covers Deferred Tax, Employee BenefitsDocumento11 pagineBatangas State University Exam Covers Deferred Tax, Employee BenefitsLouiseNessuna valutazione finora

- Comprehensive Problem Comprehensive Problem 1Documento2 pagineComprehensive Problem Comprehensive Problem 1marisaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ladies Shoes Manufacturing Unit Rs. 9.93 Million Sep 2014Documento22 pagineLadies Shoes Manufacturing Unit Rs. 9.93 Million Sep 2014Iftekharul IslamNessuna valutazione finora

- Acc Quizzes ZZZDocumento22 pagineAcc Quizzes ZZZagspurealNessuna valutazione finora

- Tally 9 NotesDocumento17 pagineTally 9 NotesAnjali HemadeNessuna valutazione finora

- MAS 2 Responsibility Accounting Part 1Documento4 pagineMAS 2 Responsibility Accounting Part 1Jon garciaNessuna valutazione finora

- First Adoption and Fair Value Demaria DufourDocumento25 pagineFirst Adoption and Fair Value Demaria DufourAhmadi AliNessuna valutazione finora

- Accounting Policies, Changes in Accounting Estimates and ErrorsDocumento6 pagineAccounting Policies, Changes in Accounting Estimates and ErrorsGlen JavellanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Faa IDocumento18 pagineFaa INishtha RathNessuna valutazione finora

- Ifrs at A Glance IFRS 3 Business CombinationsDocumento5 pagineIfrs at A Glance IFRS 3 Business CombinationsNoor Ul Hussain MirzaNessuna valutazione finora

- Specialized Investments - g5Documento15 pagineSpecialized Investments - g5KaonashiNessuna valutazione finora

- SFIN Demo - Configuration DocumentDocumento105 pagineSFIN Demo - Configuration DocumentPavan SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- We Don't Talk About BrunoDocumento5 pagineWe Don't Talk About BrunoSiúnNessuna valutazione finora

- Project Management to Revenue Recognition PrinciplesDocumento3 pagineProject Management to Revenue Recognition PrinciplesbalajicivNessuna valutazione finora

- Test Bank: Theory of AccountsDocumento241 pagineTest Bank: Theory of Accountsdeeznuts100% (1)

- MT1 Ch28Documento9 pagineMT1 Ch28api-3725162100% (1)

- Intellectual Property RightsDocumento34 pagineIntellectual Property RightsLaksha ChibberNessuna valutazione finora

- B.Com Investment FundamentalsDocumento168 pagineB.Com Investment FundamentalsPriyanshu BhattNessuna valutazione finora

- B4 IfaDocumento4 pagineB4 IfaadnanNessuna valutazione finora

- Beams11 ppt04Documento49 pagineBeams11 ppt04Rika RieksNessuna valutazione finora

- September 1 - AndrewDocumento11 pagineSeptember 1 - AndrewDrewNessuna valutazione finora

- SDE Philippines Financial StatementsDocumento41 pagineSDE Philippines Financial StatementsRonaldNessuna valutazione finora

- 4 Audit of InvestmentsDocumento11 pagine4 Audit of InvestmentsMarcus MonocayNessuna valutazione finora

- Cma Data BlankDocumento14 pagineCma Data BlankSonu NehraNessuna valutazione finora

- Sugar Factory CaseDocumento21 pagineSugar Factory CaseNarayan PrustyNessuna valutazione finora

- CFAB Accounting Chapter 12. Company Financial Statements Under IFRSDocumento17 pagineCFAB Accounting Chapter 12. Company Financial Statements Under IFRSHuy NguyenNessuna valutazione finora

- Barth Etal The Relevance of The Value Relevance AnotherviewDocumento28 pagineBarth Etal The Relevance of The Value Relevance AnotherviewMaz ShuliztNessuna valutazione finora

- Financial Statement Analysis TechniquesDocumento50 pagineFinancial Statement Analysis TechniquesTyra Joyce RevadaviaNessuna valutazione finora

- Task of MidtermDocumento10 pagineTask of MidtermNaurah Atika DinaNessuna valutazione finora

- I Will Teach You to Be Rich: No Guilt. No Excuses. No B.S. Just a 6-Week Program That Works (Second Edition)Da EverandI Will Teach You to Be Rich: No Guilt. No Excuses. No B.S. Just a 6-Week Program That Works (Second Edition)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (12)

- The Science of Prosperity: How to Attract Wealth, Health, and Happiness Through the Power of Your MindDa EverandThe Science of Prosperity: How to Attract Wealth, Health, and Happiness Through the Power of Your MindValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (231)

- Excel for Beginners 2023: A Step-by-Step and Quick Reference Guide to Master the Fundamentals, Formulas, Functions, & Charts in Excel with Practical Examples | A Complete Excel Shortcuts Cheat SheetDa EverandExcel for Beginners 2023: A Step-by-Step and Quick Reference Guide to Master the Fundamentals, Formulas, Functions, & Charts in Excel with Practical Examples | A Complete Excel Shortcuts Cheat SheetNessuna valutazione finora

- Finance Basics (HBR 20-Minute Manager Series)Da EverandFinance Basics (HBR 20-Minute Manager Series)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (32)

- How to Start a Business: Mastering Small Business, What You Need to Know to Build and Grow It, from Scratch to Launch and How to Deal With LLC Taxes and Accounting (2 in 1)Da EverandHow to Start a Business: Mastering Small Business, What You Need to Know to Build and Grow It, from Scratch to Launch and How to Deal With LLC Taxes and Accounting (2 in 1)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (5)

- Profit First for Therapists: A Simple Framework for Financial FreedomDa EverandProfit First for Therapists: A Simple Framework for Financial FreedomNessuna valutazione finora

- Financial Accounting For Dummies: 2nd EditionDa EverandFinancial Accounting For Dummies: 2nd EditionValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (10)

- The ZERO Percent: Secrets of the United States, the Power of Trust, Nationality, Banking and ZERO TAXES!Da EverandThe ZERO Percent: Secrets of the United States, the Power of Trust, Nationality, Banking and ZERO TAXES!Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (14)

- Love Your Life Not Theirs: 7 Money Habits for Living the Life You WantDa EverandLove Your Life Not Theirs: 7 Money Habits for Living the Life You WantValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (146)

- Tax-Free Wealth: How to Build Massive Wealth by Permanently Lowering Your TaxesDa EverandTax-Free Wealth: How to Build Massive Wealth by Permanently Lowering Your TaxesNessuna valutazione finora

- LLC Beginner's Guide: The Most Updated Guide on How to Start, Grow, and Run your Single-Member Limited Liability CompanyDa EverandLLC Beginner's Guide: The Most Updated Guide on How to Start, Grow, and Run your Single-Member Limited Liability CompanyValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- Financial Intelligence: A Manager's Guide to Knowing What the Numbers Really MeanDa EverandFinancial Intelligence: A Manager's Guide to Knowing What the Numbers Really MeanValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (79)

- The E-Myth Chief Financial Officer: Why Most Small Businesses Run Out of Money and What to Do About ItDa EverandThe E-Myth Chief Financial Officer: Why Most Small Businesses Run Out of Money and What to Do About ItValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (13)

- Financial Accounting - Want to Become Financial Accountant in 30 Days?Da EverandFinancial Accounting - Want to Become Financial Accountant in 30 Days?Valutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (1)

- Basic Accounting: Service Business Study GuideDa EverandBasic Accounting: Service Business Study GuideValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (2)