Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Ebook Closed Download 17 HumanResource

Caricato da

Jasmeet SinghTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Ebook Closed Download 17 HumanResource

Caricato da

Jasmeet SinghCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Dudo von Eckardstein and Julia Brandl

Human Resource Management in Nonprofit

Organizations

1. Theoretical Foundations and Related Research

Human resource management (HRM) as a discipline within economic

research has developed over the past 30 to 50 years with the focus being

primarily on business enterprises. In the meantime, many enterprises,

especially larger ones, have become highly professional in doing HRM.

Following this trend, the role that HRM plays within scientific research has

also increased. This development was mainly driven by two forces. First, the

expenditures for personnel especially in nonproductive industries often

consume more than half of the revenue or total costs. Second, personnel has

an enormous influence on organizational performance. In a situation of

intense competition, it is therefore important for companies to concentrate on

HRM in order to improve their own performance and to reduce their costs.

As far as nonprofit organizations (NPOs) and public sector organizations

are concerned, forces of competition, limited access to resources and need for

performance improvement have, although with some delay, become highly

relevant (Horack/Heimerl, 2002: 180f.; Zimmer/Priller/Hallmann, 2003:

40f.). In general, responsible managers in NPOs realized much later the need

for implementing professional HRM, even though NPOs have relatively

higher expenditures for personnel than their forprofit counterparts due to their

service orientation. In the meantime, the pressure for rationalization has also

grown in many NPOs. As a result, personnel is increasingly regarded as a

valuable resource, and HRM, in turn, has become a critical instrument for

organizational success. As a further consequence, institutionalized HRM, i.e.,

the HR function per se, is becoming more professional in NPOs.

Following these developments, academic research interest increasingly

focuses on examining HRM (or the effort to implement HRM) in NPOs at

different levels. At the conceptual level it is asked if and how HRM, which

was originally conceptualized for business enterprises, can be transferred to

NPOs. The transferability of management instruments to the specific case of

NPOs is discussed widely for almost every management function. Conclusions at this point differ and depend on the specific functions under

examination. For accounting systems, for example, a transfer seems to be

298

Dudo von Eckardstein and Julia Brandl

possible without fundamental changes. Other functions such as financing, on

the other hand, require more in-depth analysis. For the field of financing,

existing instruments must be expanded in order to account for specific aspects

of NPOs such as fundraising. For the HR function, additional questions arise

as well. Mayerhofer (2003), for example, discusses whether volunteers, who

are an important if not a constitutive element of NPOs, should be regarded as

personnel at all. A positive answer to this question would be a precondition

for the application of HRM instruments. Other authors wonder whether the

unique character of NPOs (especially their non-economic values, which also

affect the treatment of personnel) can be retained when HRM instruments

inspired by forprofit companies management strategies are applied (see

also Krnes 2001 with respect to the Protestant Church). There is fear that as

a result of increasing commercialization, NPOs might lose their specific

character, such as the trust that they enjoy (especially in the area of social

services) and their ability to recruit and keep volunteers (Simsa, 2002: 138f.)

Purpose of This Chapter

In general, the central task of human resource management is to secure

quantitatively the availability of human resources and to ensure quality levels

of the work carried out by employees (in proportion to cost). If HRM is

neglected, the efficiency of the organization could be endangered. More than

any other type of organization, NPOs depend on their employees

performance so that they can fulfill quality expectations. They also need to

ensure that labor costs are at an acceptable level. Therefore, excellent employee performance is the most basic condition for the survival of any organization (Capelli/Crocker-Hefter, 1996). Increasing competition for employees

as well as for funds will force NPOs to rethink their current HRM activities in

order to become more cost-sensitive, efficient, and effective.1 It is therefore

worth asking whether and how the principles of human resource management

can be transferred to NPOs in the same way they were developed for profitoriented organizations over the past 20 years.

The purpose of this chapter is to outline the ways HRM can stabilize and

increase the efficiency of NPOs. To do so, special attention must be paid to

the specific characteristics of NPOs. As the technical term human resource

management already indicates, the management perspective will be the focus.

The management perspective implies that the viewpoint of the top

management of the NPOs will be adopted (e.g., the one of a secretary general,

managing director, or executive committee). It only seems sensible to adopt

1

The extent to which these challenges affect NPOs and the necessity to become more

professional in terms of HRM varies between NPOs. As this article aims at giving a general

overview, we will focus on aspects which are relevant for different types of NPO.

Human Resource Management

299

this perspective for the case of relatively large NPOs. If NPOs are relatively

small (especially when they are still in their formation process), there does not

seem to be much room for strategic personnel management. This is mainly

due to the special ad hoc character of management decisions in smaller

organizations.

2.

Special Conditions for HRM in NPOs

NPOs can be described by a number of characteristics that allow them to be

distinguished from profit-oriented enterprises and public sector organizations.

These aspects must be taken into account whenever HRM tools are designed

or converted to fit the NPO case. In recent years HRM in NPOs also has

become a matter of particular interest to many researchers. Research in this

area is primarily concerned with the effects that specific characteristics of

NPOs (which will be examined below) have on the development and

implementation of HRM concepts.

Mission Instead of Profit as an Institutional Goal

A particular characteristic of NPOs is their pursuit of a mission, in the

fields of, for example, culture, sports, politics or social service. In contrast to

profit-oriented enterprises, the highest goal of the nonprofit organization is

the fulfillment of this mission, not the maximization of profit. Thus, within

the organization, attention is focused on the realization of non-economic

values. These values must be expressed in strategic plans. They also need to

be transferred into the daily application of HRM in order to secure, both

internally and externally, the success of the NPO. The Protestant Church is a

good example at this point (Krnes, 2001). This idea completely rules out a

predominantly instrumental use of employees. Instead, within NPOs the

individual as such can claim benefits or satisfaction from the realization of the

organizational mission.

Structure of Employees in NPOs

Many NPOs differ from profit-oriented enterprises and public sector

organizations due to the particular composition of their labor force. A main

characteristic of profit-oriented enterprises and public sector organizations is

that employees almost exclusively work for remuneration (i.e., in order to

earn a living). For many NPOs it is common that volunteers are active in

addition to paid employees (who themselves often receive a much smaller

300

Dudo von Eckardstein and Julia Brandl

remuneration than the prevailing market rate). Due to their status, volunteers

do not receive any remuneration at all (Badelt, 1985; Wehling, 1993). In most

social service NPOs, community service workers must be added as a third

group of employees. These community service workers are often required by

law to work in NPOs. As a result of this complex situation, HRM must adjust

itself to the respective combination of paid workers, volunteers and those

carrying out community service. It is a strategic HRM decision to choose an

appropriate combination of these groups (in terms of size).

Motivation Structure of NPOs Employees

Following what has been said previously regarding the importance of

voluntary employment in NPOs, it can be concluded that NPO management

needs to implement motivational tools that substantially differ from the ones

typically employed in profit-oriented enterprises. This has consequences for

HRM practices, too. First of all, voluntary activity means that an activity is

done for its own sake (honors sake). The aim of such an activity is to reach

a goal or to create an externality that derives from the NPOs mission. The

motivation of employees in NPOs is predominately intrinsic. The usual

function of management as motivators or stimulators of performance is

therefore unnecessary because the employees are already highly motivated.

On the one hand, this results in less pressure for managers, especially if

one assumes that many employees in the forprofit sector do not feel at all

motivated by their tasks, but only by the payment they receive. On the other

hand, the possibility is not given in NPOs to stimulate a desired behavior

through money and other incentives. Volunteers themselves determine

whether, how, with what intensity, and how long they want to be active in

their organization. Therefore, if looked at under the aspect of influence

possibilities, this situation creates at the same time both problems and

opportunities. Current empirical research about the commitment motives of

volunteers offers a more differentiated picture of the motivation. It can be

concluded from recent findings in the literature that apart from the activity

itself, employees are motivated by their desire for a meaningful use of spare

time, social networking, their desire to gain valuable experiences, and the

wish to extend their own range of knowledge through learning (see, e.g.,

Gensicke, 2000: 78).

Summing up, special requirements for HRM in NPOs result from the

parallel existence of mostly income-related motivational structures (for paid

employees) and non-income-related motivational structures (for volunteers

and possibly for community service workers).

Human Resource Management

301

Specific Restrictions on the Use of Volunteers

Voluntary activity is subject to certain restrictions that have special relevance

for the HRM of NPOs. Taking on volunteers implicitly presumes that the

person hired has a reliable income that covers living expenses. Volunteers

therefore have to receive other income from third parties (such as full-time

employment income, pensions, or support from employed husband, wife or

parents). Only in some cases are volunteers wealthy enough to cover their

living expenses completely. Furthermore, voluntary service commitments in

combination with other duties can lead to a degree of involvement that is

com-parable to full-time employment. As a consequence, volunteers usually

only work a limited amount of time per week or month for the NPO due to

other pressing activities.

Limited Availability of Performance Benchmarks and Cost Standards

NPOs often develop in areas where there are no market rules to regulate

economic activity. Clients of the services often have no clear expectations

about the quality, quantity, and cost of the services they receive. If NPO

managers cannot refer to market standards as reference cases, they will find it

difficult to value their employees achievements. Under these circumstances,

the NPO itself needs to define service standards, e.g., on the basis of direct

agreements between the provider and the recipient of the goods and services.

The lack of reference cases often also applies to personnel expenditure.

A significant number of NPOs either have no or only low personnel costs

because their employees do not receive any remuneration for their activities.

In other NPOs, personnel costs can be quite high. In this case, costs crucially

depend on the proportion of volunteers and paid employees. In a third case,

personnel costs exist and can be compared to other firms. In this case,

however, personnel costs have no effect on the organizations performance

because they are directly refunded by other organizations, e.g., by the

community or the state.

3. Instruments of HRM

Choosing the Appropriate Mix of Employees Within an NPO

A large number of NPOs can be characterized by a mix of different types of

employees, such as full-time and part-time employees, unpaid volunteers,

302

Dudo von Eckardstein and Julia Brandl

fully remunerated employees and, in certain cases, even community service

workers. This being the case, management has to choose the right mix of

employees (in terms of the composition of all workforce categories). Choices

need to be made regarding the proportions or the representation of certain

groups of employees in relation to the overall structure of employees depending on the kind of activities that are to be carried out (Wehling, 1993).

Thus far, no general rules regarding the optimal mix or composition of

employees in an organization have emerged. The following recommendations

offer practical guidelines. In general, as in any organization, key criteria for

employees are their availability, their qualifications and the overall cost level.

Availability refers to the recruitment possibilities on the external job

market. The availability of the various types of employees will affect the

mix. For example, the potential for part-time employees, volunteers and

community service workers on the external job market is limited, especially

since NPOs compete for these groups of employees among themselves. The

criterion of availability also covers the fact that part-time employees and

especially volunteers tend to quit their engagement for the NPO after a

relatively short employment time.

Volunteers and community workers in particular are not always in

possession of the required qualifications for the field in which they are

working. Therefore, specific training is necessary at the beginning of the

employment period. If no such training is carried out, the NPO risks lowquality performance. If neither qualified adequately nor trained appropriately,

these groups of employees are often assigned simple tasks. Over a longer

period of time, it might lead to a decrease of their intrinsic motivation.

The aspect of cost economies relates to labor costs. In relation to unpaid

volunteers or community workers, labor cost levels in NPOs can be quite high

for those parts of the workforce that are fully compensated. The use of

volunteers can lead to cost advantages, which in turn is an argument in favor

of employing relatively large numbers of volunteers (in terms of their

proportion to total workforce, cf. Gaskin, 1996; von Eckardstein/

Mayerhofer/Raberger, 2001). As the proportion of volunteers increases, paid

employees often tend to worry about their job security. In order to avoid

competition among different groups of employees, management might adopt

dysfunctional personnel strategies for volunteers. Another cost factor can be

derived from personnel structure: Training volunteers and community workers means relatively high worktime-specific costs of qualification because of

the generally short payback periods for these education investments. This

makes education investments for full-time employees more economical.

Finally, coordination and interface problems contribute to the limited use

of volunteer staff. On the other hand the volunteer staffing policy must be

seen from the perspective of creating potential opportunities for highly

motivated part-time employees in the future. Coordination problems and other

Human Resource Management

303

difficulties thus should be seen related to this potential.

Structuring can be done also giving consideration to other criteria, e.g.,

by aiming at a mixed age structure in order to avoid obsolescence with its

unfavorable consequences or by aiming at an appropriate gender structure

within the different fields of work.

Recruitment

Recruiting serves to create the personnel structure or to maintain it. Basically

the importance of diligent recruitment rises with the length of employment,

requirements for qualification and motivation as well as the wage demands.

Staff selection procedures are based on the existence of applicants.

Therefore recruiting actually starts with external communication to increase

the number of potential applicants. It is advisable to broaden the applicant

pool by target group marketing over different communication channels

(advertisements, articles in newspapers, contacts made by existing employees).

The most common instrument for staff selection is the interview, which is

based on an analysis of the application documents or a personnel questionnaire. Interviews are an opportunity to become acquainted with the applicant

personally. On the other hand applicants need information as well, which

influences their decision-making, and wrong decisions can be reduced on

both sides. To reduce subjectivity, it is helpful to include a second interviewer

or to assign an additional interview. The interview can be also standardized

by asking every applicant the same questions in the same order so that one

can compare the response behavior.

Especially for the recruitment of management staff the so-called

assessment center is recommended. Information about the applicants is obtained by observing how candidates behave under simulated work conditions.

For this purpose applicants have to accomplish different tasks (e.g.,

presentations, discussions), which reflect their future work situation.

Afterwards the observers compare their perceptions and decide which

candidate fulfilled the duties best. The use of assessment centers in selection

procedures is relatively time-consuming, but leads to a high-quality prognosis

for the future suitability of the proven applicant. They are used at present in

many large profit-oriented enterprises (see, e.g., Fisseni/Fennekels, 1995).

Sometimes organizations use knowledge, behavior and personality tests

for their candidate selection. Such tests can be useful in pre-selection if there

are large numbers of applicants. Since the connection between task fulfillment

in real work situations and test results is not discussed, the quality of their

prognoses remains still undefined.

By now, staff selection procedures for full-time paid employees in NPOs

304

Dudo von Eckardstein and Julia Brandl

are a matter of course. For volunteers by contrast, the use of selection

procedures is less widely accepted. A frequently mentioned argument for this

fact refers to the donation aspect of voluntary work, which cannot be rejected

even if the volunteers are not always reliable or qualified. Some NPOs stress

that volunteers are not only employees but also members on which they are

dependent. A further argument reflects the low costs of unpaid employees.

From a HRM perspective it is to be said that volunteers contribute to the

quality of performance as much as other employees. Applying professional

selection procedures could therefore improve performance quality and lower

costs.

Organization of Work

The organization of work consists of two steps, both having strategic

importance: First, the tasks are specified for each employee, second, it must

be decided whether the employee accomplishes these tasks individually or

within a group structure.

Task definition is critical for job requirement levels, for demands (von

Eckardstein et al., 1995: 192), and for the attractiveness of the job activity. A

general rule is: The narrower the task is defined, the lower are the job

requirements for the activity and the smaller is the attractiveness of the work

for the identification possibilities, which are connected with the task, and also

regarding remuneration. On the other hand, the advantage of narrowly defined

tasks resides in the fact that they can be done by a relatively large number of

employees after only a short briefing.

The second organizational parameter is the decision between individual

or group work. Recent trends in the profit-oriented economy show that

numerous enterprises strongly promote group work as they increasingly

discover the advantages of group work concepts and seek to use them for

improved productivity.

The advantages can be explained best based on the model of the semiautonomous working group, which also represents the preferential model for

the introduction of group work. In semi-autonomous groups the members

decide about internal task distributions, sometimes also about output quantity,

about their schedule, about the replacement of temporarily absent members,

etc. The main advantages lie in the rapid, briefly closed self-management

without superiors, in quick replacement when group members leave, and in

the very effective social control of individual group members, which is

realized over task execution and problem-solving as well as learning together.

The mechanism of working groups is based on a less hierarchical organization, which makes it possible to use the advantages of self-organization in a

hierarchically structured organization without questioning hierarchy as a

Human Resource Management

305

coordination principle itself. Such group work normally presupposes that

each member controls substantial elements of the entire task assigned to the

group. Besides semi-autonomous groups, there are several other concepts for

team work (e.g., quality circles, continuous improvement processes, project

groups), which are all based on comparable principles.

Most NPOs have implemented elements of group concepts. The question

is whether the success of this concept can be further increased by intensified

shaping and additional implementation of such groups (e.g., by intensified

group socialization). The advantages of group concepts in the forprofit sector

are so highly convincing that managers of NPOs cannot really even consider

the absence of group concepts.

Cooperation between full-time employees and volunteers is a special

topic of work organization (von Eckardstein/Mayerhofer/Raberger, 2001: 144

ff.). Conflicts arise mostly as a result of the fact that volunteers feel

insufficiently informed or gerrymandered by full-time employees, so they

reject responsibility for their own duties. To improve cooperation between

both, specific solutions for each organization are needed, which can also lead

to a group-specific task separation.

Leadership

Leadership covers personal communication between unit managers and the

persons employed within an organizational unit. The purpose of this

communication is to affect the employees behavior so as to achieve the

respective goals of the organization. Under this condition, leadership makes

sense only if goals were expressly formulated for the organization. Unit

managers have to break down the goals so that they are translated into clear

actions. Leadership is an indispensable function in every organization,

although there are substantial differences between organizations concerning

the intensity of this control instrument.

The practice and theory of leadership defines important leadership

instruments each supervisor should know: feedback, employee evaluation,

and performance discussions. Feedback is communication about the evaluation of behavior as soon as possible after an observation. This happens in

positive cases in the form of acknowledgement, in negative cases as criticism.

For practical purposes, numerous rules are helpful, how such feedback

discussions can be led as effectively as possible. Employee evaluation

represents a systematic procedure to collect comprehensive information about

the achievement and the behavior of the employee being evaluated (von

Eckardstein/Schnellinger, 1978: 302). This information should be made

accessible to the employee and be discussed in detail, typically in the context

of personnel development interviews. Performance discussions constitute the

306

Dudo von Eckardstein and Julia Brandl

place to exchange assessments of past achievements and behavior and are

mostly conducted at least annually. Transparency in the process and an

orientation for future behavior are important for both participants.

In practice, leadership follows very different principles in which the

respective individuality of the involved persons as well as specific organizational aspects are reflected. Some organizations create leadership

guidelines, which include statements about the desired leadership behavior of

the superiors.

For NPOs the question of whether and how volunteers should be

integrated into leadership processes has not been convincingly answered so

far. Some organizations enter into agreements in which mutual expectations,

rights and obligations are outlined (Biedermann, 2000: 118). In hierarchically

oriented organizations such as fire brigades and rescue organizations, clear

instructions exist and have to be applied. In the context of regular interactions

(goal agreement, feedback, performance discussions), leadership has only

modest value.

HR Development

Qualification of employees refers to activities conducted by an organization

to improve the abilities of its employees to increase the quality and quantity

of output. Qualification can be called HR development if such activities

follow a longer development concept (Mayerhofer, 1999).

Important qualification components are professional education and

professional training. The goal of professional education is to enable particularly young graduates in the practice of a qualified vocational activity by

conducting an official training program that meets a set of national standards.

The aim of professional training is to enlarge and deepen vocational abilities

already acquired. In contrast to professional education, professional training

is not regulated. Its main purpose is to adapt the employees qualifications to

the qualification requirements that are necessary for the respective job or

tasks.

In the context of increasing professionalism in numerous NPOs, HR

development is very much appreciated. In considering the intensity and the

goals of qualification activities, it is essential to differentiate between a

minimum qualification for the execution of the tasks at hand and a more

general qualification. In the case of the first, the main advantage results from

cost economy; in the case of the second, a greater flexibility for new tasks is

acquired. Especially in situations that require high personal responsibility, a

broad qualification level is obligatory.

If volunteers and community service workers are active in an NPO in

addition to paid personnel, the strategic question arises whether the NPO

Human Resource Management

307

should expand its qualification programs toward these two groups. Economic

facts argue rather against including unpaid employees because they generally

work a smaller number of hours in relation to the paid employees and - in the

case of community service workers - remain only a relatively short time in the

organization. In this case the worktime-specific expenditures for the

qualification noticeably exceed those of the paid employees.

However, if investment in the qualification of unpaid workers is

systematically less, a two-class system is generated because the unpaid

employees can be assigned generally only simpler work or auxiliary activities.

From this again, the organizations inclination might be to reduce voluntary

activities and to allow unpaid employees to remain a shorter time within the

organization. One should ask instead whether a qualification policy could

increase the attractiveness of unpaid activities to the volunteer labor

market. Thus, the integration of unpaid workers could be improved, their

proportion in the organization could be increased, and conflicts between paid

and unpaid workers over the often-proclaimed lack of acknowledgement of

the latter would be reduced.

Remuneration

Within the realm of paid work, remuneration is usually regarded as a main

incentive for performance. A salary is the price for which the employees give

their work to the organization. In this market-oriented view, the amount of

payment naturally has a substantial role, since it represents a cost factor for

the organization and is generally the most important source of income for the

persons employed. Numerous organizations use payment as a main instrument for performance management. In the context of NPOs, two questions in

particular are raised: How can the amount of remuneration be determined,

and should the remuneration system be used for the control of performance?

The question about the amount of remuneration must be treated

differently for the different segments of people employed in NPOs. For paid

employees, the NPO will try to pay a wage that corresponds to the usual

market conditions for the respective activity category in order to survive in

the competition for qualified workers. Otherwise organizational performance

could be jeopardized. However it is to be pointed out that many persons

employed in NPOs are satisfied with a smaller remuneration than they would

receive in a profit-oriented enterprise for a comparable activity, due to a

strong identification with the mission of the NPO (Badelt, 2002: 124).

Improved goal-orientation is the aim of performance-oriented remuneration systems. An additional payment is connected with the achievement

of special quantitative and/or qualitative performance goals. Pay-forperformance systems generally seem to be less common in NPOs than in

308

Dudo von Eckardstein and Julia Brandl

profit-oriented enterprises. To motivate performance, their application should

be considered also for NPOs. In the context of mixed personnel structures,

however, caution is indicated since conflicts between value orientation and

income orientation are to be expected there. The remuneration of management presents a special problem: Should their compensation vary according

to their contribution to the organizations performance as is the case for highlevel personnel in forprofit enterprises (von Eckardstein, 2001)?

With paid employees, by definition the payment in cash is the main focus.

This does not generally apply for unpaid volunteers. For volunteers a nonmaterial return by representatives of the NPO in the form of

acknowledgement of their achievements holds more importance. Apart from

this, non-material privileges such as access to reasonable purchase possibilities, training and other qualification opportunities, etc. come into consideration for the acknowledgement of voluntary activity as well. Privileges for

volunteers - for instance within the social security system could also be

justified from the social context of voluntary work (e.g., Biedermann, 2000:

123 f.; Gensicke, 2000: 85).

4. HR Strategies

Concept of HR Strategy

The different instruments of HRM outlined above are interdependent and

cannot be seen without considering their context. Human resource managers

have to assume that employees are affected not so much by individual

instruments but rather by all instruments as a whole. Therefore a consistent

total concept in which the individual instruments can be arranged is needed.

These instruments represent an action program that the participants in HRM

pursue for a longer term. It is defined here as human resource strategy.

With the development of such a concept, a fit of instruments is to be

aimed at in the sense that individual instruments mutually strengthen each

others effect, or at least do not obstruct each other (horizontal fit). The

question of a vertical fit also arises: This includes the harmonizing of the

personnel strategy with relevant contextual conditions on the one hand and

the strategic goals of the NPO on the other hand. It is evident that a fit of

relevant contextual conditions and organizational goals with the personnel

strategy is more favorable for the performance of the NPO than an

independent personnel strategy. Nevertheless fits in the horizontal and

vertical dimensions cannot be monitored regularly (von Eckardstein, 2003:

392f.). Human resource strategies are not controlled by logic, by developing

Human Resource Management

309

action programs on the basis of relevant contextual factors and organizational

goals, which must then just be converted by the responsible persons. They

rather reflect the subjective logic of the participants and the culture of an

organization (von Eckardstein/Mayerhofer, 2001: 227f.). Human resource

strategies depend on whether and how conditions are assessed and how they

are converted from organization goals into action programs (von

Eckardstein/Mayerhofer, 2001). Every human resource strategy is connected

with a basic idea, a philosophy, which the participants share and put into

action. Basic ideas or philosophies of the participants as well as the organizational culture do not change on short notice; they are longer-term stable

constructs. Their function in the context of HRM is to put the complexity of

HRM action and appropriate planning into a frame of reference and thereby

to make it describable. Thus the classification of individual instruments

within a general context is made easier. The responsible person has to ask

whether and to what extent these instruments are compatible with organizational goals, circumstantial factors, and the philosophy and organizational

culture (see Eckardstein/Simsa: Strategic management, in this book).

Designing HR Strategies

The following section outlines prescriptive and empirical aspects of HR

strategies in NPOs. The prescriptive perspective offers organizational

recommendations, while the empirical perspective focuses on the practical

shape of HR strategies in NPOs.

From a prescriptive viewpoint, numerous recommendations regarding

instruments and measures can be found in the literature, primarily with

reference to paid personnel in enterprises (see, e.g., Pfeffer, 1994; Berthel,

2000; Drumm, 2000; Oechsler, 1997; Klimecki/Gmuer, 2001). These

recommendations express the best practice of HRM without regard to

sector-specific conditions. Beyond that, more NPO-specific recommendations

exist in the literature about NPO management (e.g., Herman, 1994;

Naehrlich/Zimmer, 2000, therein esp. Biedermann; Pidgeon, 1998 with

reference to volunteers). These volumes recommend highly proven HR

strategies with a general validity. However, they lack any link with situational

conditions such as participants, pursued goals or types of NPOs. This is not to

diminish the value of these recommendations because they contain numerous

valuable suggestions. Nevertheless, they are often too general for direct

application and include too little information about how to set priorities under

specific conditions. In this context the findings of Simsa (2001) appear

remarkable. Simsa describes different influence strategies NPOs can exert on

other organizations based on two dimensions: divergence of logic and

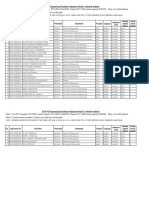

interpretation tendencies and extent of coupling. The four HR strategies

310

Dudo von Eckardstein and Julia Brandl

that result from the matrix of these two dimensions in the picture below can

be assigned to specific types of NPOs. Simsa differentiates between influence

strategies based on confron-tation, which apply to human rights

organizations, for example. To ensure acceptance by their surroundings and

to fulfill background activities, these organizations should offer internal

career brackets, also with a focus on older employees. Cooperative influence

strategies are typical for membership associations, which try to exert

influence through negotiations with other organizations. For them HRM must

concentrate on the selection of personnel and employee development to

strengthen the employees commitment to the organizations goals. Damage

limiting strategies are focused on the reduction of negative effects and are

very appropriate for aid organizations. HRM should concentrate on protecting

employees from burnout effects and loss of motivation through coaching and

team development. The dominance of service provision, which applies mainly

to NPOs in the cultural and social fields, requires high professionalism of the

NPO personnel because of the competitive environment. HRM can support

this, for example, by defining quality standards for employees. There are only

a few empirical studies about HR strategies pursued by NPOs. Empirical

research in HR strategies still is at the beginning in general, and this is true

particularly for NPOs. Ridder/Neumann (2001) find in an exploratory study

(hospitals and nursing facilities in Lower Saxony/Germany) that the vertical

fit between general management and institutional HRM is only weakly

evident, since responsible HR managers are rarely consulted for strategic

questions with impact on HRM. They concentrate on the operational activities

of HRM instead. For quantitative personnel planning as well as for qualitative

staffing, they follow instructions from external sponsors. Management by

objectives as a leadership tool is seldom found. A HR strategy taking

horizontal fit into account does not exist.

Another exploratory investigation based on twelve case studies of social

service NPOs in eastern Austria (von Eckardstein/Mayerhofer, 2001) with a

focus on volunteers found a different staffing pattern for voluntary

employees. They are assigned within the operational range as either

additional to paid employees in order to support the work of the

latter and/or

equivalent, i.e., with the same tasks as paid employees, or

exclusively for the execution of operational tasks, while paid

employees concentrate their activities on management tasks.

A second finding shows substantial differences for the development level of

HRM. On one hand, there are NPOs using only few HR instruments and

mostly not in a purposeful and systematic way (lacking in particular HR

development). On the other side of the spectrum, a highly developed HRM

can be observed, characterized by the use of comprehensive instruments that

Human Resource Management

311

are coordinated among themselves (horizontal) as well as with the organizations goals (vertical). While the first case is found very often in smaller

NPOs, the latter mostly applies to large NPOs in the sector of social services.

A third set of findings refers to whether the NPO sees differences in

qualification and achievement among volunteers and how these differences

are handled. This perspective is important for the maintenance and

improvement of performance quality and highlights the question how NPOs

react to differences in their volunteers performance and qualification. From

the combination of two criteria (development level and handling differences),

a four-field matrix can be developed with four types of HR strategy (selective,

harmonizing, differentiating, leveling). The sample allows a first empirical

insight into HRM strategies in NPOs. Results show that on one hand NPOs

with a highly developed HRM emphasize performance and quality

orientation; on the other hand there are NPOs stressing the community of

volunteers and the acknowledgement of the donated work (harmonizing

human resource strategy). Both developments reflect specific philosophies

of participants and organizational culture. In terms of strategy development

these conceptual frameworks can be used as analytical tools for selfdescription of the actual HR strategy as well as for the definition of strategic

goals.

Human Resource Management Dependent on the Type of NPO?

The NPO sector as such is quite heterogeneous. NPOs can be classified according to a number of criteria (Badelt, 2002a: 70f.), for example, the purpose of the NPO (membership, service, advocacy, or support), its stage of development, its size, and its proximity to private sector companies, to public

sector organizations or to society as a whole (Zauner, 2002: 174). A classification of NPOs could be carried out also according to their geographic

affiliation (e.g., Eastern European countries, transition economies, Western

European countries, U.S.A.). Following this idea of heterogeneity among

NPOs, the question arises whether HRM should be differentiated, too,

according to the type of NPO. A second question is whether there is even

empirical evidence for potential differences in HR strategies.

As far as the main functions of personnel management are concerned

(such as the recruitment, management, and remuneration of employees), it is

suggested that from a purely prescriptive perspective, these functions are the

same for any kind of organization (i.e., regardless of its nonprofit or forprofit

nature). Mayrhofer/Scheuch explicitly point this out saying that management

functions need to be carried out regardless of the specific character of an

NPO (Mayrhofer/Scheuch, 2002: 100). Employees need to be recruited, managed, and remunerated independent of whether they work in a hospital or for

312

Dudo von Eckardstein and Julia Brandl

a political party. Volunteers need to be recruited, too. By definition, however,

they do not receive any remuneration (in monetary terms). Following these

considerations, it is therefore not controversial to assume that NPOs carry out

their HRM functions (such as recruitment or management) with a varying intensity. Recruitment in NPOs might be a less complex task if there are volunteers that approach the NPO themselves with the intention to work for it (in

comparison to the case where the NPO needs to engage actively in costly recruitment activities). As far as the objectives pursued with these HR functions

are concerned, there are potential differences among NPOs, however. It is

suggested that NPOs should treat their employees in the same manner or with

the same set of values as they proclaim themselves. A religious order that is

itself obliged to dutifulness should therefore apply this itself as a key governance principle. v. Eckardstein/Ridder have formulated, with the necessary

precaution, a number of hypotheses regarding the relationship of NPO types

and the focus of their personnel strategies (v. Eckardstein/Ridder, 2003: 18f.).

Simsa, too, recommends differentiating personnel strategies in NPOs according to type of NPO (Simsa, 2001; cf. 6.4.2 Designing HR Strategies). From

an empirical viewpoint, there is no information as to whether personnel strategies in NPOs clearly depend on the type of NPO. It seems more to be the

case that there are significant differences between organizations of the same

type. These differences can most likely be explained by differences in orientations of human resource managers (e.g., their own opinions or priorities) or

other situational factors.

5. Conclusion

HRM has a substantial influence on the performance and the expenditures of

NPOs. There exists an extensive body of knowledge and recommendations,

which were originally developed for profit-oriented organizations and which

can be applied in different ways to NPOs as well. However, the special characteristics of these organizations must be considered. HRM practices vary

from NPO to NPO. Single observations and case studies show that several

NPOs already use instruments for recruiting and long-term planning or develop HR strategies. But there still is a need for increased professionalism. If

the application of professional HRM instruments remains behind expectations

and needs, the question of why arises. In this area there is a lack of knowledge

about practical problems NPOs face when they implement existing recommendations for HRM. Because intensive empirical research is missing, there

are substantial gaps in this field, which are difficult to fill because of the

heterogeneity of these organizations.

Human Resource Management

313

Suggested Readings

Badelt, Ch. (ed.) (2002): Handbuch der Nonprofit Organization. Stuttgart

Berthel, J. (2002): Personal-Management, Grundzge fr Konzeptionen betrieblicher

Personalarbeit. Stuttgart

von Eckardstein, D./Ridder, H.-G. (eds.) (2003): Personalmanagement als Gestaltungsaufgabe im Nonprofit und Public Management. Mnchen

Hermann, R.D. (ed.) (1994): The Jossey-Bass Handbook of Nonprofit Leadership and

Management. San Francisco

References

Badelt, Ch. (2002a): Der Nonprofit Sektor in sterreich. In: Badelt, Ch. (ed.):

Handbuch der Nonprofit Organization. Stuttgart, pp. 63-105

Badelt, Ch. (2002b): Zwischen Marktversagen und Staatsversagen? Nonprofit

Organisationen aus soziokonomischer Sicht. In: Badelt, Ch. (ed.): Handbuch

der Nonprofit Organization. Stuttgart, pp. 107-128

Badelt, Ch. (1985): Politische konomie der Freiwilligenarbeit. Frankfurt

Berthel, J. (2000): Personal-Management. Stuttgart

Biedermann, Ch. (2000): Was heit Freiwillige managen? Grundzge des Freiwilligen-Managements. In: Nhrlich, St./Zimmer, A. (eds.): Management in Nonprofit Organisationen. Opladen, pp. 107-128

Capelli, P./Crocker-Hefter, A. (1996): Distinctive Human Resources are Firms Core

Competencies. In: Organizational Dynamics, 24/3, pp. 7-22

Drumm, H.J. (2000): Personalwirtschaftslehre. Berlin

von Eckardstein, D. (2003): Personalmanagement, in Kasper, H./Mayerhofer, W.

(eds.): Personalmanagement, Fhrung, Organisation. Wien, pp. 361-446

von Eckardstein, D. (2001): Variable Vergtung fr Fhrungskrfte als Instrument

der Unternehmensfhrung. In: von Eckardstein, D. (ed.) (2001): Handbuch Variable Vergtung fr Fhrungskrfte. Mnchen, pp. 1-25

von Eckardstein, D. (1995): Zur Modernisierung betrieblicher Entlohnungssysteme in

industriellen Unternehmen. In: von Eckardstein, D./Janes, A. (eds.) (1995): Neue

Wege der Lohnfindung fr die Industrie. Wien, pp. 1539

von Eckardstein D./Mayerhofer, H. (2001): Personalstrategien fr Ehrenamtliche in

sozialen NPOs. In: Zeitschrift fr Personalforschung, No. 3, pp. 225-242

von Eckardstein, D./Mayerhofer, H./Raberger, M.-Th. (2001): Personalstrategien fr

Ehrenamtliche in sozialen NPOs. Projektbericht, Wien

von Eckardstein, D./Ridder, H.G. (2003): Anregungspotenziale fr Nonprofit Organisationen aus der wissenschaftlichen Diskussion ber strategisches Personalmanagement. In: von Eckardstein, D./Ridder, H.G. (eds.): Personalmanagement

als Gestaltungsaufgabe im Nonprofit und Public Management. Mnchen, pp. 1131

von Eckardstein, D./Schnellinger, F. (1978): Betriebliche Personalpolitik. Mnchen

Fisseni, H.-J./Fennekels, G.P. (1995): Das Assessment-Center. Gttingen

Gaskin, K. et al. (1996): Ein neues brgerschaftliches Europa. Untersuchung zur Verbreitung und Rolle von Volunteering in Europa. Freiburg

314

Dudo von Eckardstein and Julia Brandl

Gensicke, Th. (2000): Freiwilliges Engagement in den neuen und alten Lndern. In:

Bundesministerium fr Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend (ed.): Freiwilliges

Engagement in Deutschland (No.2). Stuttgart, pp. 22-113

Hermann, R.D. et al. (1994): The Jossey-Bass Handbook of Nonprofit Leadership and

Management. San Francisco

Horak, Ch./Heimerl, P. (2002): Management von NPOs eine Einfhrung. In: Badelt,

Ch. (ed.): Handbuch der Nonprofit Organization. Stuttgart, pp. 181-195

Klimecki, R.G./Gmr, M. (2001): Personalmanagement. Stuttgart

Krnes, G.V. (2001): Personalmanagement in der Evangelischen Kirche. In: Zeitschrift fr Personalforschung, No. 3, pp. 321-335

Mayerhofer, H. (2003): Der Stellenwert Ehrenamtlicher als Personal in Nonprofit

Organization. In: v. Eckardstein, D./Ridder, H.G. (eds.): Personalmanagement als

Gestaltungsaufgabe im Nonprofit und Public Management. Mnchen, pp. 97-118

Mayerhofer, H. (1999): Qualifikationsmanagement. In: v. Eckardstein, D./Kasper,

H./Mayerhofer, W. (ed.): Management. Stuttgart, pp. 489-520

Mayerhofer, W./Scheuch, F. (2002): Zwischen Ntzlichkeit und Gewinn: Nonprofit

Organisationen aus betriebswirtschaftlicher Sicht. In: Badelt, Ch. (ed.): Handbuch der Nonprofit Organisation. Stuttgart, pp. 87-105

Nhrlich, St./Zimmer, A. (eds.) (2000): Management in Nonprofit Organisationen.

Opladen

Oechsler, W.A. (1997): Personal und Arbeit. Mnchen

Pfeffer, J. (1994): Competitive Advantage through People. Boston

Pidgeon, W.P. jr. (1998): The Universal Benefits of Volunteering. New York

Ridder, H.-G./Neumann, P. (2001): Personalwirtschaft im Umbruch? Empirische

Ergebnisse und theoretische Erklrung. In: Zeitschrift fr Personalforschung, No.

3, pp. 243-262

Simsa, R. (2002): NPOs und die Gesellschaft: Eine vielschichtige und komplexe

Beziehung Soziologische Perspektiven. In: Badelt, Ch. (ed.): Handbuch der

Nonprofit Organisation. Stuttgart, pp. 129-152

Simsa, R. (2001): Einflussstrategien von Nonprofit-Organisationen: Ausprgungen

und Konsequenzen fr das Personalmanagement. In: Zeitschrift fr Personalforschung, No. 3, pp. 284-305

Wehling, M. (1993): Personalmanagement fr unbezahlte Arbeitskrfte. BergischGladbach

Zauner, A. (2002): ber Solidaritt zu Wissen. Ein systemtheoretischer Zugang zu

Nonprofit Organisationen. In: Badelt, Ch. (ed.): Handbuch der Nonprofit

Organization. Stuttgart, pp. 153-177

Zimmer, A./Priller, E./Hallmann, Th. (2003): Zur Entwicklung des Nonprofit Sektors

und zu den Auswirkungen auf das Personalmanagement seiner Organisationen.

In: v. Eckardstein, D./Ridder, H.G. (ed.): Personalmanagement als Gestaltungsaufgabe im Nonprofit und Public Management. Mnchen, pp. 3352

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Ebook Closed Download 23 MarketingDocumento31 pagineEbook Closed Download 23 MarketingJasmeet SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- 9.1 Banking Law - ProfessionalDocumento394 pagine9.1 Banking Law - ProfessionalMaryam KhalidNessuna valutazione finora

- BCGPPTDocumento21 pagineBCGPPTSourav PaulNessuna valutazione finora

- Indian Partnership Act essentialsDocumento19 pagineIndian Partnership Act essentialstedaaNessuna valutazione finora

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Declaration On Schools As Safe SanctuariesDocumento3 pagineDeclaration On Schools As Safe SanctuariesFred MednickNessuna valutazione finora

- Reflective Essay 2Documento2 pagineReflective Essay 2api-356760616Nessuna valutazione finora

- FS 2 - Episode 2 Intended Learning Outcomes Lesson Objectives As My Guiding StarDocumento12 pagineFS 2 - Episode 2 Intended Learning Outcomes Lesson Objectives As My Guiding StarHenry Kahal Orio Jr.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Llb-3-Ledger 14022023Documento147 pagineLlb-3-Ledger 14022023Sujata ChaskarNessuna valutazione finora

- HSIR14 Professional EthicsDocumento7 pagineHSIR14 Professional EthicsAjeeth BNessuna valutazione finora

- Format PORTFOLIO IN THE TEACHER AND THE SCHOOL CURRICULUMDocumento24 pagineFormat PORTFOLIO IN THE TEACHER AND THE SCHOOL CURRICULUMJohn Lloyd Jumao-asNessuna valutazione finora

- The Inner Life of TeachersDocumento2 pagineThe Inner Life of TeachersRodney Tan67% (3)

- Taguig Integrated School: Name of StudentsDocumento8 pagineTaguig Integrated School: Name of StudentsSherren Marie NalaNessuna valutazione finora

- School Action Plan in Altenative Learning SystemDocumento2 pagineSchool Action Plan in Altenative Learning SystemROXANNE PACULDARNessuna valutazione finora

- Goal Statement Walden University PDFDocumento2 pagineGoal Statement Walden University PDFVenus Makhaukani100% (1)

- Kellogg's Career Development CaseDocumento2 pagineKellogg's Career Development CaseSnigdhaNessuna valutazione finora

- Improving The Teaching of Personal Pronouns Through The Use of Jum-P' Language Game Muhammad Afiq Bin IsmailDocumento5 pagineImproving The Teaching of Personal Pronouns Through The Use of Jum-P' Language Game Muhammad Afiq Bin IsmailFirdaussi HashimNessuna valutazione finora

- Impulse and Momentum Collision Science ClassDocumento4 pagineImpulse and Momentum Collision Science ClassJenny PartozaNessuna valutazione finora

- Tracer Study Reviews Literature on Graduate EmploymentDocumento17 pagineTracer Study Reviews Literature on Graduate EmploymentMay Ann OmoyonNessuna valutazione finora

- Technology Philosophy StatementDocumento3 pagineTechnology Philosophy Statementapi-531476080Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lucas Edenfield Resume AdminDocumento3 pagineLucas Edenfield Resume Adminapi-239363393Nessuna valutazione finora

- Maths PedagogyDocumento30 pagineMaths PedagogyNafia Akhter100% (1)

- Argument Writing Claim Reasons Evidence PDFDocumento9 pagineArgument Writing Claim Reasons Evidence PDFEam Nna SerallivNessuna valutazione finora

- .Sustainable Tourism Course OutlineDocumento8 pagine.Sustainable Tourism Course OutlineAngelica LozadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Anecdotal RecordDocumento11 pagineAnecdotal RecordJake Floyd Morales100% (1)

- Metacognition-Based Reading Program Boosts ComprehensionDocumento10 pagineMetacognition-Based Reading Program Boosts ComprehensionLeo Vigil Molina BatuctocNessuna valutazione finora

- 0610 w04 Ms 1Documento4 pagine0610 w04 Ms 1Hubbak Khan100% (4)

- 171934210Documento4 pagine171934210Henry LimantonoNessuna valutazione finora

- Educational Problem of SC and STDocumento4 pagineEducational Problem of SC and STSubhendu GhoshNessuna valutazione finora

- Tuli Co Application FormDocumento9 pagineTuli Co Application FormchinkiNessuna valutazione finora

- Learning Plans in The Context of The 21 CenturyDocumento62 pagineLearning Plans in The Context of The 21 CenturyAnna Rica SicangNessuna valutazione finora

- Letter For Work ImmersionDocumento4 pagineLetter For Work ImmersionAne SierasNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter Four The Audio-Lingual MethodDocumento6 pagineChapter Four The Audio-Lingual Methodapi-274521031Nessuna valutazione finora

- White FB 2 LP Weaving Le Revised 1Documento12 pagineWhite FB 2 LP Weaving Le Revised 1api-600746476Nessuna valutazione finora

- Unit 3 (WPH03) June 2014Documento21 pagineUnit 3 (WPH03) June 2014Web BooksNessuna valutazione finora