Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Psychology of Value

Caricato da

filsoofDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Psychology of Value

Caricato da

filsoofCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Values, De!

elopment of

perspectives on their parents socialization efforts.

How do children interpret, resist, and negotiate

parental messages? Lastly, the phenomenon of bidirectional influence needs to be better understood.

This is because the processes underlying childrens

receptivity and resistance to parental influence and of

parental receptivity and vulnerability to childrens

influence are still largely unexplored.

See also: Altruism and Prosocial Behavior, Sociology

of; Ethics and Values; Kohlberg, Lawrence (192787);

Moral Development: Cross-cultural Perspectives;

Moral Education; Moral Reasoning in Psychology;

Piaget, Jean (18961980); Piagets Theory of Human

Development and Education; School Outcomes:

Cognitive Function, Achievements, Social Skills, and

Values; Values: Psychological Perspectives; Values,

Sociology of

Bibliography

Bandura A, Walters R H 1963 Social Learning and Personality

De!elopment. Holt Rinehart and Winston, New York

Bugental D B, Goodnow J J 1998 Socialization processes. In:

Damon W, Eisenberg N (eds.) Handbook of Child Psychology,

5th edn. Wiley, New York, pp. 389462

Grolnick W S, Deci E L, Ryan R M 1997 Internalization within

the family: A self-determination theory perspective. In: Grusec

J E, Kuczynski L (eds.) Parenting and Childrens Internalization of Values: A Handbook of Contemporary Theory.

Wiley, New York, pp. 13561

Grusec J E 1997 A history of research on parenting strategies.

In: Grusec J E, Kuczynski L (eds.) Parenting and Childrens

Internalization of Values: A Handbook of Contemporary

Theory. Wiley, New York, pp. 322

Grusec J E, Goodnow J J 1994 Impact of parental discipline

methods on the childs internalization of values: A reconceptualization of current points of view. De!elopmental

Psychology 30: 419

Hoffman M L 1970 Moral development. In: Mussen P H (ed.)

Carmichaels Manual of Child Psychology, 3rd edn. Wiley,

New York, pp. 261360

Kuczynski L 1984 Socialization goals and mother-child interaction: Strategies for long-term and short-term compliance.

De!elopmental Psychology 20: 106173

Kuczynski L, Harach L, Bernardini S C 1999 Psychologys child

meets sociologys child: Agency, influence and power in

parentchild relationships. In: Shehan C L (ed.) Through the

Eyes of the Child: Re!isioning Children as Acti!e Agents of

Family Life. JAI Press, Stanford, CT, pp. 2152

Kuczynski L, Hildebrandt N 1997 Models of conformity and

resistance in socialization theory. In: Grusec J E, Kuczynski L

(eds.) Parenting and Childrens Internalization of Values: A

Handbook of Contemporary Theory. Wiley, New York,

pp. 22756

Kuczynski L, Marshall S, Schell K 1997 Value socialization in a

bidirectional context. In: Grusec J E, Kuczynski L (eds.)

Parenting and Childrens Internalization of Values: A Handbook of Contemporary Theory. Wiley, New York, pp. 2350

Lawrence J A, Valsiner J 1993 Conceptual roots of internalization: From transmission to transformation. Human

De!elopment 36: 15067

16150

Maccoby E E, Martin J A 1983 Socialization in the context of

the family: parent-child interaction. In: Hetherington E M

(ed.) Handbook of Child Psychology: Socialization, Personality

and Social De!elopment. Wiley, New York, pp. 1101

Schwartz S 1992 Universals in the content and structure of

values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20

countries. In: Zanna M (ed.) Ad!ances in Experimental

Social Psychology. Academic Press, Orlando, FL, pp. 165

Smetana J 1997 Parenting and the development of social

knowledge reconceptualized: A social domain analysis. In:

Grusec J E, Kuczynski L (eds.) Parenting and Childrens

Internalization of Values: A Handbook of Contemporary

Theory. Wiley, New York, pp. 16292

Wrong D H 1961 The oversocialized conception of man in

modern society. American Sociological Re!iew 26: 18393

L. Kuczynski

Values: Psychological Perspectives

1. O!er!iew

This article asks the following questions: what are

values and how are values distinguishable from related

concepts like motives, goals and attitudes? Are values

located within individuals or social structures?

Values are difficult to study and persistent questions

arise as to whether they are real, whether they

actually can be shown to have causal influence on

behavior. Yet much of everyday life is cast in terms of

valuesthink of ethics, law, religion, politics, art,

child rearing, and more. Abstract value judgments are

embodied in seeming gut reactions that something is

right, moral, or natural vs. wrong, immoral, or

unnatural. Another way to see values in action is to

contrast cultures or subcultures in what seems right,

natural, or moral. One of the great contributions of

cultural and cross-cultural research is the way that it

brings Western cultural values into sharp relief.

Americans are said to value life, liberty, and the

pursuit of happiness. But what does value mean?

Implicitly or explicitly we evaluate or assign value to

everythingregarding things as good or bad, a truth

or falsity, a virtue or a vice. How do we know? One

important means is through values. Values can be

thought of as priorities, internal compasses or springboards for actionmoral imperatives. In this way,

values or mores are implicit or explicit guides for

action, general scripts framing what is sought after

and what is to be avoided.

2. Definitions

Modern theories of values are grounded in the work of

Kohn (class and values), Rokeach (general value

systems), and Kluckhohn (group level). Values can be

Values: Psychological Perspecti!es

conceptualized on the individual and group level. At

the individual level, values are internalized social

representations or moral beliefs that people appeal to

as the ultimate rationale for their actions. Though

individuals in a society are likely to differ in the

relative importance assigned to a particular value;

values are an internalization of sociocultural goals

that provide a means of self-regulation of impulses

that would otherwise bring individuals in conflict with

the needs of the groups and structures within which

they live. Thus, discussion of values is intimately tied

with social life. At the group level, values are scripts or

cultural ideals held in common by members of a

group; the groups social mind. Differences in these

cultural ideals, especially those with a moral component, determine and distinguish different social

systems. In this sense Webers Protestant ethic and

spirit of capitalism describe value systems.

Values, to which individuals feel they owe an

allegiance as members of a particular group or society,

are seen as the glue that makes social life possible

within groups. Yet, they also set the stage for frictions

and lack of consensual harmony in intergroup interactions. Values are thus at the heart of the human

enterprise; embedded in social systems, they are what

makes social order both possible and resistant to

change. Values are not simply individual traits; they

are social agreements about what is right, good, to be

cherished.

What is common to all value phenomena? At the

individual level, values contain cognitive and affective

elements and have a selective or directional quality;

they are internalized. Preference, judgment, and action

are commonly explained in terms of values. Individuals take on values as part of socialization into a

family, group and society. Once taken on, values are

assumed relatively fixed over time (see Values, De!elopment of ). Indeed, values that are individually

endorsed and highly accessible to the individual do

predict that individuals behavior. Conversely, even

personally endorsed values wont influence action

when they are not made salient to the individual at the

time of action. Moreover, in any given situation more

than one personally endorsed value may apply, and

the behavioral choice appropriate for one value may

conflict with the behavioral choice appropriate to

another value.

Values are codes or general principles guiding

action, they are not the actions themselves nor are they

specific checklists of what to do and when to do it.

Thus, two societies can both value achievement but

differ tremendously in their norms as to what to

achieve, how to achieve, and when pursuing achievement is appropriate. Values underlie the sanctions for

some behavioral choices and the rewards for others. A

value system presents what is expected and hoped for,

what is required and what is forbidden. It is not a

report of actual behavior but a system of criteria by

which behavior is judged and sanctions applied.

Values scaffold likes and dislikes, what feels pleasant

and unpleasant, and what is deemed a success or

failure. Values and value systems are often evoked as

rationales for action; for example, values of freedom

and equality were evoked to elicit American support

for the Civil Rights movements. Values differ from

goals in that values provide a general rationale for

more specific goals and motivate attainment of goals

through particular methods.

3. History and Current De!elopments

Initially viewed with suspicion by Western social

scientists as too subjective for scientific study, the

concept of values found increasing use beginning with

The Polish Peasant in Europe and America (Thomas

and Znaniecki 1921). Impetus for the study of cultural

values comes from the work of Alfred Kroeber, Clyde

Kluckhohn, Talcott Parsons, Charles Morris, Robert

Redfield, Ralph Linton, Raymond Firth, A. I.

Hallowell, and more currently Milton Rokeach and

Shalom Schwartz.

Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck (1961) proposed that

cultural value systems are variations of a set of basic

value orientations that flow from answers to basic

questions about being: (a) What is human nature

evil, neutral, mixed, or good? (b) How do we relate to

nature or supernaturalsubjugation, harmony, or

mastery? (c) What is the nature of timepast, present,

future? (d) What is the nature of human activity

being, being-in-becoming, doing? (e) What is the

nature of our relationship to othersare we joined

vertically, horizontally or are we simply separate

individuals? They also organized a system for comparing values in terms of their level of generalization and

function in discourse and conduct, proposing that

values fit into a pyramid of ascending generalization.

For each society, a few central or focal values were

proposed to constitute a mutually interdependent set

of what makes for the good life. These include the

unquestioned, self-justifying premises of the value

system and definitions of basic and general value

terms; for example, happiness, virtue, beauty, and

morality.

Since American researchers dominated values research, much early work focused on documenting

American values. Need for achievement as an American value, and concern over decline in the centrality of

this orientation appear as early as 1944 (Spates 1983).

Values studies documented the influence of education,

age, type of employment, and socioeconomic status on

value preferences of Americans, adding to Webers

thesis of the influence of religion (Protestantism vs.

Catholicism) on achievement and work values in

Europe. Kohn (1977) was responsible for a number of

important values surveys documenting that in various

European countries and the US, parents of higher

socioeconomic status value self-direction in their

16151

Values: Psychological Perspecti!es

children more than parents of lower educational and

occupational levels. These findings have been verified

cross-nationally in 122 societies.

Extending the documentation of American values,

Rokeach (1973) validated empirically 36 values related

to preferred end states and preferred ways of behaving.

Using Rokeachs scale, value differences tied to class,

age, race, subculture, and level of differences were

documented in many countries. Building on Rokeach,

Schwartz (1992) delineates values as ways of articulating universal requirements of human existenceto

survive physically, have social interchange, and provide group continuity. For Schwartz, values represent

operationalizations of these needs as goals that fit

together in meaningful clusters (achievement, selfdirection, stimulation, hedonism, universalism, benevolence, tradition, conformity, security, and power).

Some clusters are compatible (e.g., stimulation and

hedonism) and others compete (e.g., self-direction and

conformity).

Using mostly data from teachers and college students in 20 primarily Western countries, Schwartz

shows that, with the exception of China, specific values

mostly do cluster and compete as expected. Thus,

honest, forgiving, and helpful cluster together as

benevolence, and self-direction, and stimulation

cluster far from conformity, tradition, and security. These data suggest important universality to

how values are organized cross-culturally and that

societies differ in which clusters of values predominate

public life.

4. Contro!ersies

Key tensions in the values literature focus on the

conditions under which they may influence behavior,

and the appropriate level of analyses for seeing values

in action. Interest in values as a research focus has

ebbed in the past as each paradigm for studying values

has been criticized for lack of specificity of findings as

due to values and not other social norms, attitudes or

situational constraints. Current cultural psychology

focuses attention on social structures as the repository

of values such as personal freedom, group harmony,

personal happiness, and duty or filial piety.

How do we know that values exist? A number of

options are available: (a) Individual testimony

people say what values they hold.Yet, self-reports of

values are subject to pronounced context effects (see

Attitudes and Beha!ior). (b) Behavioral choiceseither

in naturalistic or laboratory settings, value differences

may be imputed from behavior. Yet, behavior is

influenced by many variables other than values. At the

individual level, values themselves are assumed to link

to behaviors via their influence on norms and attitudes,

but people may infer their values from their behavior,

reversing the causal relationship. (c) Cultural and

social structuresexpenditure of resources, time,

energy and structuring of the natural environment;

16152

cultural products can be seen as concrete residues of

value-based choices (see Cross-cultural Psychology;

Cultural Psychology). (d) Social interchange

observation of behavior in situations of conflict, and

more generally observation of what is rewarded or

punished, praised or vilified provides data for identifying what is socially valued. Here, too, the question

of appropriate evidence arises. To what extent is it

appropriate to assume that differences in social structures and societies are evidence of value differences?

Political and economic influences and simple inertia

may set the stage for behaviors, without a causal

influence of necessarily values.

5. Future Directions

Cross-cultural perspectives are currently becoming

increasingly central to values discussion. For example

Inglehart (1990) documented values and value change

in a large multinational study, and a large number of

two-nation comparison studies has emerged. Another

important topic of research is the connection between

values of individuals, values of subcultural groups,

and values of larger cultural systems and methods for

identifying and studying each of these. Perhaps in

addition to identifying value vocabularies at each

level, it is time to begin to ask whether values

appropriately are studied as fixed traits of individuals

or as embodied in groups, and to what extent values

research is synonymous with cultural and crosscultural research.

Given that any particular behavior importantly is

influenced by context effects that make certain information salient at the moment of action, it is not

surprising that the effects of individual value endorsements on behavior have a sometimes you see it,

sometimes you dont quality about them. But focusing

on individual endorsement of values may miss much

of the power of value systems to influence everyday

life. That is, individuals may not need to personally

endorse or have salient particular values in order for

their influence to be felt. The most profound influence

of values may be through the ways that they influence

rules, norms, procedures within a society, and in this

way structure the everyday life choices for individuals

within a society.

Thus, whereas previous researchers have documented values using survey techniques in which

individuals rated the extent to which various values

were important to them, future assessment of values

may need to consider more indirect approaches such as

what services a society provides its members, what

behaviors are rewarded or sanctioned and so on.

See also: School Outcomes: Cognitive Function,

Achievements, Social Skills, and Values; Values,

Anthropology of; Values, Development of; Values,

Sociology of; Vocational Interests, Values, and

Preferences, Psychology of

Values, Sociology of

Bibliography

Darley J, Shultz T 1990 Moral rules: Their content and

acquisition. Annual Re!iew of Psychology 41: 52556

Inglehart R 1990 Culture Shift in Ad!anced Industrial Society.

Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

Kluckhohn F, Strodtbeck F 1961 Variations in Value Orientations. Row, Peterson, Evanston, IL

Kohn M 1977 Class and Conformity. University of Chicago

Press, Chicago

Rokeach M 1973 The Nature of Human Values. Free Press, New

York

Schooler C 1996 Cultural and social-structural explanations of

cross-national psychological differences. Annual Re!iew of

Sociology 22: 32349

Schwartz S 1992 Universals in the content and structure of

values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Ad!ances in Experimental Social Psychology 25: 166

Spates J 1983 The sociology of values. Annual Re!iew of

Sociology 9: 2749

Sullivan J, Transue J 1999 The psychological underpinnings of

democracy: A selective review of research on political tolerance, interpersonal trust, and social capital. Annual Re!iew

of Psychology 50: 62550

Thomas W, Znaniecki K 1921 The Polish Peasant in Europe and

America. Chicago University Press, Chicago

D. Oyserman

Values, Sociology of

Everything social actors appreciate, appraise, wish to

obtain, recommend, set up or propose as an ideal, can

be considered as a value. Ideas, emotions, moral

deeds, acts, attitudes, institutions, material things, etc.

may possess this special quality by virtue of which they

are appraised, desired, or recommended. But what is

attractive for some, can be repulsive to others. Thus,

to values correspond countervalues which are underrated, disapproved, rejected. Nationalism and internationalism, private and public property, freedom and

equality, etc., may be, according to diverse actors,

values or countervalues.

1. Dimensions of the Concept

Four main dimensions of the concept can be distinguished:

(a) Each value has an object, i.e. what is valued,

prized. The nation, Moslem faith, work, profit, instruction, leisure, honesty, the family, etc., may become values. Any element of social reality, of the

spiritual and moral world, can have a value aspect

insofar it is praised or refused, advocated, or condemned.

(b) This object is qualified by a judgment as valuable

or contemptible, as good or bad, as useful or useless,

as true or false, as desirable or not, as beautiful or

ugly, etc. The sentence expressed is a value judgment.

One will say, e.g., that ones country is inviolable and

its enemies are unkind, that Moslem faith is true

and unbelievers are mistaken, that work is sacred and

profits are unjust, that honesty is a virtue while robbery

is dishonest, and so on. Value judgments answer to a

large set of principles and criteria whereby opinions,

beliefs, convictions are shaped, choices are made.

(c) Values become norms when they command

and!or regulate conducts, prescribe a course of action.

Norms tend to conform behavior and commitments to

the values confessed. If your country is inviolable, you

should defend it, if Islam is true, you must comply with

its prescriptions, if profits are unjust, you must fight

against them, if instruction is important, you must

learn, if honesty is a virtue, you are not allowed to

misappropriate funds. Values provide the grounds for

accepting or rejecting particular norms, and norms are

standards for actual conduct.

(d) The !alue holders are either individual or

collective actors or social groups. Therefore one can

speak of the values of such and such person, of the

liberals, of the middle class, of the teenagers, of the

Russians, or of Bantu culture.

The concept of value is inseparable from the notion

of preference. To value one object rather than another

(e.g. to prefer a party of cards to the theater) means

that in a given situation the value inducing the

choice was adopted or inculcated to the detriment of

another.

2. Value Systems: Definition

The values of an individual or a collectivity do not

appear as sharply separated and independent units.

Instead, they are bound together, are interdependent,

they form a system. When a new value is acquired or

an old one is lost, when a value is weakening (lowering)

or strengthening (rising), the whole system will be

affected.

A system of values is hierarchically built up. It is

also a scale of values. Often the difference between

actors does not proceed from the content of their

systems, but from their difference in ranking their

values. For example, in the abortion debate, all

participants may highly prize the value of life, but

some will emphasize the conceived childs future while

others will take into account the mothers decision.

The actor is more or less tied to certain values than

to others. Values contain not only cognitive elements,

they involve strong affective components too. The

more a value is deeply rooted, the more it takes a

central place in the system and the more it is lived

intensely, arouses emotions, and mobilizes vehement

energies. There are values men are ready to die for.

The mode of organizing a system of values varies

from one culture to another. Its inner logic does not

obey the same rules. This fact is undoubtedly the main

reason why misunderstanding prevails between

peoples pertaining to different cultures, each one

interpreting the world in its own terms.

16153

Copyright ! 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved.

International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences

ISBN: 0-08-043076-7

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- DebatabaseDocumento241 pagineDebatabaseMukhlisa AnvarovaNessuna valutazione finora

- Roh 1Documento97 pagineRoh 1Hemantha KumarNessuna valutazione finora

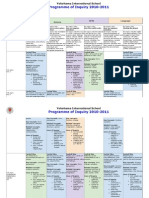

- Yokohama International School Programme of InquiryDocumento5 pagineYokohama International School Programme of Inquiryvaibhav_shukla_9Nessuna valutazione finora

- Research MethodologyDocumento353 pagineResearch MethodologyJohny86% (59)

- Week 6 - The Quantitative MethodDocumento5 pagineWeek 6 - The Quantitative MethodIsrael PopeNessuna valutazione finora

- Day 3 - Handout For Problem Objectives TreeDocumento6 pagineDay 3 - Handout For Problem Objectives TreePaolo Gerard TolentinoNessuna valutazione finora

- Business Research Methods Important 2 MarksDocumento7 pagineBusiness Research Methods Important 2 MarksDaniel Jk100% (4)

- English-For-Acad G12 q1Documento91 pagineEnglish-For-Acad G12 q1Nicole Hernandez100% (9)

- Muhammad Al-GhazaliDocumento7 pagineMuhammad Al-Ghazaliapi-247725573Nessuna valutazione finora

- 490 (23) Shoemaker Self-ReferenceDocumento4 pagine490 (23) Shoemaker Self-ReferencefilsoofNessuna valutazione finora

- B. Smith, 'Christian Von Ehrenfels On Value'Documento18 pagineB. Smith, 'Christian Von Ehrenfels On Value'Santiago de ArmaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Metaphysics of Value: Subjective/Objective TheoriesDocumento4 pagineThe Metaphysics of Value: Subjective/Objective TheoriesfilsoofNessuna valutazione finora

- CognitivityDocumento33 pagineCognitivityfilsoofNessuna valutazione finora

- CognitivityDocumento33 pagineCognitivityfilsoofNessuna valutazione finora

- Germino Fact-ValueDocumento5 pagineGermino Fact-Valuetinman2009Nessuna valutazione finora

- Neurophilosophy of MindDocumento4 pagineNeurophilosophy of MindfilsoofNessuna valutazione finora

- Germino Fact-ValueDocumento5 pagineGermino Fact-Valuetinman2009Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ofphilosophyinth 00 StiruoftDocumento52 pagineOfphilosophyinth 00 StiruoftfilsoofNessuna valutazione finora

- Germino Fact-ValueDocumento5 pagineGermino Fact-Valuetinman2009Nessuna valutazione finora

- Germino Fact-ValueDocumento5 pagineGermino Fact-Valuetinman2009Nessuna valutazione finora

- PHIL398Documento7 paginePHIL398filsoofNessuna valutazione finora

- PHIL398Documento7 paginePHIL398filsoofNessuna valutazione finora

- Contemporary WarfareDocumento16 pagineContemporary WarfareASUPREMEANessuna valutazione finora

- Cause and EffectDocumento6 pagineCause and EffectVengelo CasapaoNessuna valutazione finora

- BOHMAN - New Philosophy of Social Science PDFDocumento9 pagineBOHMAN - New Philosophy of Social Science PDFAnna PinheiroNessuna valutazione finora

- Data Science and Its Relationship To Big Data and Data-Driven Decision MakingDocumento19 pagineData Science and Its Relationship To Big Data and Data-Driven Decision MakinggomehhNessuna valutazione finora

- Understanding Compensatory Internet UseDocumento4 pagineUnderstanding Compensatory Internet UseEsperanza TorricoNessuna valutazione finora

- Glossary of Philosophical TermsDocumento34 pagineGlossary of Philosophical TermsPleasant KarlNessuna valutazione finora

- Nursing Research (1day) BAVDocumento274 pagineNursing Research (1day) BAVCzarina Rae Ü CahutayNessuna valutazione finora

- Technical Communication With 2016 Mla Update 11th Edition Markel Test BankDocumento10 pagineTechnical Communication With 2016 Mla Update 11th Edition Markel Test Bankfuneralfluxions48lrx100% (31)

- Inductive and Deductive Method of ResearchDocumento3 pagineInductive and Deductive Method of ResearchDinesh KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- To Build A FireDocumento7 pagineTo Build A FireMarta ECNessuna valutazione finora

- Research Methodology Notes - Unit 1Documento19 pagineResearch Methodology Notes - Unit 1parag nimjeNessuna valutazione finora

- Predictive Safety From Near Miss and Hazard Reporting: Written by Bernard Borg, CSPDocumento18 paginePredictive Safety From Near Miss and Hazard Reporting: Written by Bernard Borg, CSPChristian Olascoaga MoriNessuna valutazione finora

- FanboysDocumento1 paginaFanboysYeliz KelesNessuna valutazione finora

- Nagarjuna by John DunneDocumento5 pagineNagarjuna by John DunneTim HardwickNessuna valutazione finora

- Vanajenahalli Layout Plan-24!07!2023 - OddDocumento1 paginaVanajenahalli Layout Plan-24!07!2023 - Oddhrtechnologies.vendorsNessuna valutazione finora

- Aqm AssignmentDocumento8 pagineAqm AssignmentJyoti RawalNessuna valutazione finora

- TME351 Part I - L5 - 13rd Oct 2019Documento26 pagineTME351 Part I - L5 - 13rd Oct 2019Firas Abu talebNessuna valutazione finora

- The Material Life of Human Beings: Artifacts, Behavior, and Communication. Michael Brian Schiffer With Andrea RDocumento2 pagineThe Material Life of Human Beings: Artifacts, Behavior, and Communication. Michael Brian Schiffer With Andrea RinlovewithmyselfNessuna valutazione finora

- Research Aptitude by Talvir PDFDocumento27 pagineResearch Aptitude by Talvir PDFPranit Satyavan Naik50% (2)

- Jerry Fodor SurveyDocumento9 pagineJerry Fodor SurveyluisimbachNessuna valutazione finora

- Metacritic of KantDocumento9 pagineMetacritic of KantCamilo Torres MestraNessuna valutazione finora