Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Bastiat

Caricato da

Paul-ishDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Bastiat

Caricato da

Paul-ishCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Frédéric Bastiat

BY THOMAS J. DILORENZO

C

laude Frédéric Bastiat was a French economist, legisla-

tor, and writer who championed private property, free

markets, and opposed all government intervention.

The main underlying theme of Bastiat’s writings was that the

free market was inherently a source of “economic harmony”

among individuals, as long as government was restricted to

the function of protecting the lives, liberties, and property of

citizens from theft or aggression. To Bastiat, governmental

coercion was only legitimate if it served “to guarantee security

of person, liberty, and property rights, to cause justice to reign

over all.”

Bastiat emphasized the plan-coordination function of the

free market, a major theme of the Austrian School, because his

thinking was influenced by some of Adam Smith’s writings

and by the great French free-

market economists Jean-Baptiste

Say, François Quesnay, Destutt

de Tracy, Charles Comte, Richard

Cantillon (who was born in Ire-

land and emigrated to France),

and Anne Robert Jacques Turgot.

Thomas J. DiLorenzo teaches econom-

ics at Loyola College in Maryland.

2 Who is Frédéric Bastiat?

These French economists were among the precursors to

the modern Austrian School, having first developed such con-

cepts as the market as a dynamic, rivalrous process, the free-

market evolution of money, subjective value theory, the laws

of diminishing marginal utility and marginal returns, the mar-

ginal productivity theory of resource pricing, and the futility

of price controls in particular and of the government’s eco-

nomic interventionism in general.

Bastiat was orphaned at age ten, and was raised and edu-

cated by his paternal grandparents. He left school at age 17 to

work in the family exporting business in the town of Bay-

onne, where he learned firsthand the evils of protectionism

by observing all the closed-down warehouses, the declining

population, and the increased poverty and unemployment

caused by trade restrictions.

When his grandfather died, Bastiat, at age 25, inherited

the family estate in Mugron, which enabled him to live the life

of a gentleman farmer and scholar for the next 20 years. Bas-

tiat hired people to operate the family farm so he could con-

centrate on his intellectual pursuits. He was a voracious

reader, and he discussed and debated with friends virtually

all forms of literature.

Bastiat’s first published article appeared in April of 1834.

It was a response to a petition by the merchants of Bordeaux,

Le Havre, and Lyons to eliminate tariffs on agricultural prod-

ucts but to maintain them on manufacturing goods. Bastiat

praised the merchants for their position on agricultural prod-

ucts, but excoriated them for their hypocrisy in wanting pro-

tectionism for themselves. “You demand privilege for a few,”

he wrote, whereas “I demand liberty for all.” He then

explained why all tariffs should be abolished completely.

Bastiat continued to hone his arguments in favor of eco-

nomic freedom by writing a second essay in opposition to all

domestic taxes on wine, entitled “The Tax and the Vine,” and

a third essay opposing all taxes on land and all forms of trade

Who is Frédéric Bastiat? 3

restrictions. Then, in the summer of 1844, Bastiat sent an unso-

licited manuscript on the effects of French and English tariffs

to the most prestigious economics journal in France, the Jour-

nal des Economistes. The editors published the article, “The

Influence of English and French Tariffs,” in the October 1844

issue, and it unquestionably became the most persuasive

argument for free trade in particular, and for economic free-

dom in general, that had ever appeared in France, if not all of

Europe.

After 20 years of intense

intellectual preparation, articles

began to pour out of Bastiat, The way in which

and soon took the form of his Bastiat described

first book, Economic Sophisms, economics as an

which to this day is still intellectual endeavor is

arguably the best literary virtually identical to what

defense of free trade available. modern Austrians label

He quickly followed with his the science of human

second book, Economic Har- action, or praxaeology.

monies, and his articles were

reprinted in newspapers and

magazines all over France.

In 1846, he was elected a corresponding member of the

French Academy of Science, and his work was immediately

translated into English, Spanish, Italian, and German. Free-

trade associations soon began to sprout up in Belgium, Italy,

Sweden, Prussia, and Germany, and were all based on Bas-

tiat’s French Free Trade Association.

While Bastiat was shaping economic opinion in France,

Karl Marx was writing Das Kapital, and the socialist notion of

“class conflict” that the economic gains of capitalists necessar-

ily came at the expense of workers was gaining in popularity.

Bastiat’s Economic Harmonies explained why the opposite is

true that the interests of mankind are essentially harmonious

if they can be cultivated in a free society where government

confines its responsibilities to suppressing thieves, murderers,

4 Who is Frédéric Bastiat?

and special-interest groups who seek to use the state as a

means of plundering their fellow citizens.

The way in which Bastiat described economics as an intel-

lectual endeavor is virtually identical to what modern Austri-

ans label the science of human action, or praxaeology. While

establishing the inherent harmony of voluntary trade, Bastiat

also explained how governmental resource allocation is neces-

sarily antagonistic and destructive of the free market’s natural

harmony.

Bastiat also saw through the phony “philanthropy” of the

socialists who constantly proposed helping this or that person

or group by plundering the wealth of other innocent members

of society through the aegis of the state. All such schemes are

based on “legal plunder, organized injustice.”

Bastiat’s writing constitutes an intellectual bridge

between the ideas of the pre-Austrian economists and the

Austrian tradition of Carl Menger and his students. He was

also a model of scholarship for those Austrians who believed

that general economic education, especially the kind of eco-

nomic education that shatters the myriad myths and supersti-

tions created by the state and its intellectual apologists, is an

essential function (if not duty) of the economist.

To this day, Bastiat’s work is not appreciated as much as it

should be because, as Murray Rothbard explained, today’s

intemperate critics of economic freedom “find it difficult to

believe that anyone who is ardently and consistently in favor

of laissez-faire could possibly be an important scholar and eco-

nomic theorist.”

The Ludwig von Mises Institute

518 West Magnolia Avenue, Auburn, Alabama 36832

phone 334-321-2100 • fax 334-321-2119

email info@mises.org • web mises.org

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- WORK STUDY (WORK MEASUREMENT & METHOD STUDY) of PRODUCTION TECHNOLOGYDocumento72 pagineWORK STUDY (WORK MEASUREMENT & METHOD STUDY) of PRODUCTION TECHNOLOGYvvns451988885% (131)

- Intellectual Property Code Edited RFBTDocumento135 pagineIntellectual Property Code Edited RFBTRobelyn Asuna LegaraNessuna valutazione finora

- Evaluating SOWsDocumento1 paginaEvaluating SOWsAnonymous M9MZInTVNessuna valutazione finora

- Zen and The Art of SellingDocumento4 pagineZen and The Art of Sellingbobheuman100% (6)

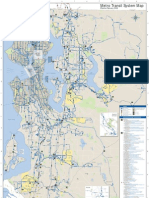

- SystemMapback 907Documento1 paginaSystemMapback 907Paul-ish100% (1)

- Coke U.S. Frozen Beverages Nutrition InformationDocumento1 paginaCoke U.S. Frozen Beverages Nutrition InformationPaul-ish100% (1)

- Pepsi Nutrition InformationDocumento11 paginePepsi Nutrition InformationPaul-ish100% (1)

- SystemMap 208Documento1 paginaSystemMap 208Paul-ishNessuna valutazione finora

- The Benefits and Hazards of The Philosophy of Ayn RandDocumento18 pagineThe Benefits and Hazards of The Philosophy of Ayn RandPaul-ish100% (4)

- Coke U.S Fountain Beverages Nutrition InformationDocumento1 paginaCoke U.S Fountain Beverages Nutrition InformationPaul-ish100% (4)

- Coke Soft Drink Nutrition InformationDocumento1 paginaCoke Soft Drink Nutrition InformationPaul-ish100% (1)

- Coke Hybrids Nutrition InformationDocumento1 paginaCoke Hybrids Nutrition InformationPaul-ishNessuna valutazione finora

- Coke Seagrams Nutrition InformationDocumento1 paginaCoke Seagrams Nutrition InformationPaul-ish100% (2)

- POWERade Nutrition InformationDocumento1 paginaPOWERade Nutrition InformationPaul-ish86% (7)

- Minute Maid Nutrition InformationDocumento1 paginaMinute Maid Nutrition InformationPaul-ish100% (1)

- Coke Energy Drinks Nutrition InformationDocumento2 pagineCoke Energy Drinks Nutrition InformationPaul-ish100% (3)

- Nestea Nutrition InformationDocumento2 pagineNestea Nutrition InformationPaul-ish100% (2)

- Dasani Nutrition InformationDocumento1 paginaDasani Nutrition InformationPaul-ish100% (3)

- McDonald's Specialty CoffeesDocumento2 pagineMcDonald's Specialty CoffeesPaul-ish100% (3)

- Value Freedom, Laissez Faire, Mises and Rothbard: A Comment On Prof. JonesDocumento22 pagineValue Freedom, Laissez Faire, Mises and Rothbard: A Comment On Prof. JonesPaul-ish100% (2)

- Burger King Nutritional BrochureDocumento6 pagineBurger King Nutritional BrochurePaul-ish100% (3)

- Socialism PDFDocumento21 pagineSocialism PDFTay Chye Lee RichardNessuna valutazione finora

- McDonald's Nutrition FactsDocumento10 pagineMcDonald's Nutrition FactsPaul-ish100% (4)

- A Critical Analysis of Murray Rothbard's Model For Common Law Juridical Systems in The Free SocietyDocumento56 pagineA Critical Analysis of Murray Rothbard's Model For Common Law Juridical Systems in The Free SocietyPaul-ishNessuna valutazione finora

- Wendy's NutritionDocumento8 pagineWendy's NutritionPaul-ish100% (6)

- Bo6e29 1Documento606 pagineBo6e29 1Paul-ish100% (1)

- Death, Wealth, and Taxes: Bruce BartlettDocumento13 pagineDeath, Wealth, and Taxes: Bruce BartlettPaul-ishNessuna valutazione finora

- A Private Property Reflection On Investment in Professional Football ClubsDocumento38 pagineA Private Property Reflection On Investment in Professional Football ClubsPaul-ish100% (1)

- BetrayalDocumento256 pagineBetrayalPaul-ish100% (2)

- BernardiniDocumento16 pagineBernardiniPaul-ishNessuna valutazione finora

- Economic Development: An Individualist Methodology: Amir AzadDocumento13 pagineEconomic Development: An Individualist Methodology: Amir AzadPaul-ishNessuna valutazione finora

- Azad 2Documento14 pagineAzad 2Paul-ishNessuna valutazione finora

- Austrian Theory Trade Cycle: Ludwig Von Mises Gottfried Haberler Murray N. Rothbard Friedrich A. HayekDocumento111 pagineAustrian Theory Trade Cycle: Ludwig Von Mises Gottfried Haberler Murray N. Rothbard Friedrich A. HayekPaul-ishNessuna valutazione finora

- Personal Characteristics of An Entrepreneur: Department of Management SciencesDocumento32 paginePersonal Characteristics of An Entrepreneur: Department of Management Sciencesshani27100% (1)

- Advertisment For Consultant Grade-I in VAC VerticalDocumento2 pagineAdvertisment For Consultant Grade-I in VAC VerticalSiddharth GuptaNessuna valutazione finora

- Entry Strategy and Strategic Alliances: Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinDocumento40 pagineEntry Strategy and Strategic Alliances: Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinMardhiah RamlanNessuna valutazione finora

- 10 Proven Templates For Writing Value Propositions That WorkDocumento6 pagine10 Proven Templates For Writing Value Propositions That WorkGeo GlennNessuna valutazione finora

- Feb 16th 2015 PDFDocumento60 pagineFeb 16th 2015 PDFPeter K NjugunaNessuna valutazione finora

- January 2019 1546422160 241kanagaDocumento3 pagineJanuary 2019 1546422160 241kanagaArtem ZenNessuna valutazione finora

- BADM6020 Train&Dev Quiz Ch3 1Documento3 pagineBADM6020 Train&Dev Quiz Ch3 1Jasmin FelicianoNessuna valutazione finora

- Maslows Hierarchy of Needs in The Business Setting PDFDocumento4 pagineMaslows Hierarchy of Needs in The Business Setting PDFKim Taehyung0% (1)

- Report in Oral CommDocumento6 pagineReport in Oral CommellieNessuna valutazione finora

- Innovative Teaching and Learning StrategiesDocumento3 pagineInnovative Teaching and Learning StrategiesMornisaNessuna valutazione finora

- 9.chapter 06 PDFDocumento18 pagine9.chapter 06 PDFIshrahaNessuna valutazione finora

- Narrative Report - TalaDocumento3 pagineNarrative Report - TalaRichmond Lloyd Menguito JavierNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Prepare For MCAT (Study Schedule)Documento28 pagineHow To Prepare For MCAT (Study Schedule)Maria SmithNessuna valutazione finora

- Its 2011Documento359 pagineIts 2011BogdanAncaNessuna valutazione finora

- U.S. Wheat Associates: Weekly Price ReportDocumento4 pagineU.S. Wheat Associates: Weekly Price ReportSevgi BorayNessuna valutazione finora

- Marketing PDFDocumento64 pagineMarketing PDFEstefania DiazNessuna valutazione finora

- 2nd Part of XXCDocumento21 pagine2nd Part of XXCKarolina KosiorNessuna valutazione finora

- Salesmanship: A Form of Leadership: Dr. Dennis E. MaligayaDocumento22 pagineSalesmanship: A Form of Leadership: Dr. Dennis E. MaligayaDennis Esik MaligayaNessuna valutazione finora

- Wa0008Documento19 pagineWa0008YashasiviNessuna valutazione finora

- Design Improvement: Phase I. Design and Construction Phase - Testing (Functionality) Phase - Software CodeDocumento10 pagineDesign Improvement: Phase I. Design and Construction Phase - Testing (Functionality) Phase - Software CodeAbdifatah mohamedNessuna valutazione finora

- 3314-06-03-Student AssignmentDocumento4 pagine3314-06-03-Student AssignmentSkye BeatsNessuna valutazione finora

- BSBCMM401 Assessment SolutionDocumento9 pagineBSBCMM401 Assessment Solutionsonam sharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- 2 - Template - Report and ProposalDocumento6 pagine2 - Template - Report and ProposalAna SanchisNessuna valutazione finora

- Impact of ILO On Labor Laws in IndiaDocumento24 pagineImpact of ILO On Labor Laws in IndiaCacptCoachingNessuna valutazione finora

- Docking Bays PDFDocumento72 pagineDocking Bays PDFnitandNessuna valutazione finora

- Magallona Vs Exec. Secretary DigestDocumento4 pagineMagallona Vs Exec. Secretary DigestJerome LeañoNessuna valutazione finora