Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

LGBT Interviewing Poster

Caricato da

rohitabraham2012Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

LGBT Interviewing Poster

Caricato da

rohitabraham2012Copyright:

Formati disponibili

Healthcare interviewing of LGBTQ patients: Bridging the gap for medical education

Nafeeza Hussain1, Anahita Mostaghim2, Genevieve Gill-Wiehl3, Rohit Abraham4, Sagar Chawla5

1Marshall University

School of Medicine; 2Eastern Virginia Medical School; 3University of Miami Miller School of Medicine; 4Michigan State University College of Human Medicine; 5Mayo Medical School

Introduction

The LGBTQ community composes nearly 5% of the

US population1, and yet many healthcare providers feel

uncomfortable interacting with and/or providing care for

them2.

Despite laws prohibiting discrimination3, many

LGBTQ persons have been turned away or receive

suboptimal treatment from physicians4.

These experiences with healthcare services have

marginalized the LGBTQ population, preventing many

from seeking and receiving adequate healthcare.

There is a lack of LGBTQ training in medical

curricula6.

Methods

1-hr education panel and interactive training session

was given in a national setting with attendance by 28

medical students leaders from across the United States.

The open question-and-answer session followed by an

interactive session with a volunteer standardized

transgender patient allowed students to familiarize

themselves with barriers LGBTQ patients encounter in a

clinical setting, and how best to provide a supportive

environment.

A follow up survey was administered at the conclusion

of the event in order to ascertain participant feedback.

Pla

Results

Conclusions

Recruitment

Establish student

Leadership

Survey needs

Syllabus

Create curricula

Incorporate local

resources

Administrative Approval

Communicate

AAMC

guidelines

Propose LGBTQ

elective offering

Implement Coursework

Serve as local

LGBTQ training

advocate

Disseminate

training

Figure 1. From Journal of the Society of Academic Emer. Med. (2014)

Comparison of distribution of actual versus desired hours of LGBTQ health

topics by frequency in Emergency Medicine residencies (actual hours,

n = 115, SD 1.38; desired hours, n = 107, SD 2.10).

Figure 2. Attendance at LGBTQ session, which totaled at 28

medical students leaders from various schools across the nation.

Figure 4. Our model to disseminating LGBTQ training to medical

school leaders, who can then systematically integrate it at their schools

Expert panel and simulation training shows potential

as a replicable model for integration of healthcare

interviewing for LGBTQ populations in medical

education.

Students and supportive faculty can adopt the

proposed model at medical schools across the country.

AAMC Recommendations7

1. Provide education about LGBTQ health needs and role of academic

medicine in healthcare system in supporting these populations

2. Support medical schools by discussing how to integrate content into

medical education focusing on role of institutional climate

3. Provide framework to facilitate assessment of learners, curricula, and

institutions

4. Highlight national resources and curricular innovations within academic

medicine

Additional Recommendations

1. Partnering with local LGBTQ advocacy organizations to aid in planning

process and provide expert resources

2. Implementing serial/follow-up training sessions to better reinforce and

add to previous knowledge

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

Objective

5.

To demonstrate a replicable model for medical

education to include LGBTQ specific healthcare

interviewing training

6.

To disperse this model to medical student leaders

across the country

To inspire similar training at the medical school level

through student-run elective coursework focused on

LGBTQ healthcare

7.

Figure 3. LGBTQ Panel Volunteers, who also served in national

leadership positions within the American Medical Association

Figure 5. Attendee evaluations of LGBT training session

Scored on Likert Scale of 1-5, where 5 being high educational quality

and high belief there is a national need in medical education

Gates, G. J., & Newport, F. (2013, February 15). Gallup Special Report:

New Estimates of the LGBT Population in the United States.

Rubin, R. (2015). Minimizing Health Disparities Among LGBT

Patients. JAMA, 313(1), 15.

Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services. (2012, March 26). Emergency

Medical Treatment & Labor Act (EMTALA).

Ewton, T. A., & Lingas, E. O. (2015). Pilot Survey of Physician Assistants

Regarding Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Providers Suggests Role

for Workplace Nondiscrimination Policies. LGBT Health, 2(4), 357-361.

Obedin-Maliver, J., Goldsmith, E. S., Stewart, L., White, W., Tran, E.,

Brenman, S., Well, M., Fetterman, D., Garcia, G., & Lunn, M. R. (2011).

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and TransgenderRelated Content in Undergraduate

Medical Education. JAMA,306(9). Retrieved February 10, 2016.

Moll, J., Krieger, P., Moreno-Walton, L., Lee, B., Slaven, E., James, T., Hill,

D., Podolsky, S., Corbin, T., & Heron, S. L. (2014). The Prevalence of

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Education and Training in

Emergency Medicine Residency Programs: What Do We Know? Acad

Emerg Med Academic Emergency Medicine,21(5), 608-611.

Association of American Medical Colleges, AAMC Advisory Committee on

Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, and Sex Development.

(2014). Implementing Curricular and Institutional Climate Changes to

Improve Health Care for Individuals Who Are LGBT, Gender

Nonconforming, or Born with DSD [Press release]. Retrieved March 22,

2016

Potrebbero piacerti anche

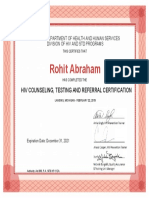

- MDHHS HIV Test Counselor CertificationDocumento1 paginaMDHHS HIV Test Counselor Certificationrohitabraham2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- AMA MedEd Innovation AbstractDocumento2 pagineAMA MedEd Innovation Abstractrohitabraham2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- Interim Teaching CertificateDocumento1 paginaInterim Teaching Certificaterohitabraham2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- Mental Heath First Aid CertificateDocumento1 paginaMental Heath First Aid Certificaterohitabraham2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- 08.23 RohitAbraham LinkedInDocumento8 pagine08.23 RohitAbraham LinkedInrohitabraham2012Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Detailed Lesson PlanDocumento6 pagineDetailed Lesson PlanLara Michelle Sanday Binudin50% (2)

- 20 Fair Trade Porn Niche Markets Feminist Audience PDFDocumento5 pagine20 Fair Trade Porn Niche Markets Feminist Audience PDFFran DonosoNessuna valutazione finora

- Psychological CriticismDocumento2 paginePsychological CriticismJohn DoeNessuna valutazione finora

- Same Sex Civil UnionDocumento6 pagineSame Sex Civil UnionVal Justin DeatrasNessuna valutazione finora

- GaramnaukraaniDocumento17 pagineGaramnaukraanigoudtsriNessuna valutazione finora

- Discussion Text 2Documento5 pagineDiscussion Text 2Faustina KadjuNessuna valutazione finora

- The FuriesDocumento16 pagineThe FuriesJoan VillanuevaNessuna valutazione finora

- My Sexual Autobiography Vol 1Documento218 pagineMy Sexual Autobiography Vol 1megan fisher50% (2)

- Finding The Power of The Erotic in Japanese Yuri MangaDocumento65 pagineFinding The Power of The Erotic in Japanese Yuri MangaDaniela HimemiyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Dowry Systems in Complex SocietiesDocumento17 pagineDowry Systems in Complex SocietiesbaredineNessuna valutazione finora

- Ultrasonography in Pregnancy: Clinical Management Guidelines For Obstetrician-Gynecologists Number 58, December 2004Documento30 pagineUltrasonography in Pregnancy: Clinical Management Guidelines For Obstetrician-Gynecologists Number 58, December 2004KamenriderNessuna valutazione finora

- Uts Lesson 9Documento6 pagineUts Lesson 9Genaro Jr. LimNessuna valutazione finora

- PrepositionDocumento5 paginePrepositionGulshanNessuna valutazione finora

- Love Systems Insider: Guide To Dates & Dating PART 1Documento4 pagineLove Systems Insider: Guide To Dates & Dating PART 1Love SystemsNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Identity Wheel Handout RevisedDocumento2 pagineSocial Identity Wheel Handout Revisedapi-563955428Nessuna valutazione finora

- Violence Against Women ViewpointsDocumento208 pagineViolence Against Women ViewpointsDanny GoldstoneNessuna valutazione finora

- Chemicals of LoveDocumento3 pagineChemicals of LoveSabina DiacNessuna valutazione finora

- Ca Form 19-10Documento128 pagineCa Form 19-10Panneer SelvamNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is EnglishDocumento1 paginaWhat Is EnglishSon Burnyoaz100% (1)

- 3 Compresssed Notes Selection & SpeciationDocumento7 pagine3 Compresssed Notes Selection & SpeciationLIM ZHI SHUENNessuna valutazione finora

- Marisol Pagan v. Alberto Gonzalez, 3rd Cir. (2011)Documento4 pagineMarisol Pagan v. Alberto Gonzalez, 3rd Cir. (2011)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Perna - Viridis - Asian Green MusselDocumento4 paginePerna - Viridis - Asian Green MusselJanet ManuelNessuna valutazione finora

- Gender-Fair Media Guidebook Revised Edition FinalDocumento75 pagineGender-Fair Media Guidebook Revised Edition FinalallenNessuna valutazione finora

- A Semiotics Analysis of A Guess AdvertDocumento8 pagineA Semiotics Analysis of A Guess AdvertCaoimhe CoyleNessuna valutazione finora

- Digest - PP vs. Ramirez (Prostitution) January 30 CaseDocumento3 pagineDigest - PP vs. Ramirez (Prostitution) January 30 CaseSam LeynesNessuna valutazione finora

- Basic Spanish Guide PDFDocumento32 pagineBasic Spanish Guide PDFRogério Nistico100% (1)

- 26 Supremo Amicus 378Documento7 pagine26 Supremo Amicus 378smera singhNessuna valutazione finora

- Manual On Quality Standads For HIV Testing Laboratories NacoDocumento137 pagineManual On Quality Standads For HIV Testing Laboratories NacoMohandoss Murugesan0% (1)

- Poem For Your Sprog - Collected WorksDocumento1.082 paginePoem For Your Sprog - Collected WorksTomas Weisbek100% (1)

- Chromosomal Karyotyping Chromosomal KaryotypingDocumento14 pagineChromosomal Karyotyping Chromosomal KaryotypingTimothy23 SiregarNessuna valutazione finora