Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Wiley American Anthropological Association: Info/about/policies/terms - JSP

Caricato da

Jossias Hélder HumbaneTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Wiley American Anthropological Association: Info/about/policies/terms - JSP

Caricato da

Jossias Hélder HumbaneCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Unofficial Histories: A Vision of Anthropology from the Margins

Author(s): Louise Lamphere

Source: American Anthropologist, Vol. 106, No. 1 (Mar., 2004), pp. 126-139

Published by: Wiley on behalf of the American Anthropological Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3567447

Accessed: 04-03-2016 13:30 UTC

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/

info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content

in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship.

For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Anthropological Association and Wiley are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

American Anthropologist.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 196.11.235.231 on Fri, 04 Mar 2016 13:30:34 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

LOUISE LAMPHERE

PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS

100th AAA ANNUAL MEETING, WASHINGTON, D.C., DECEMBER 2001

Unofficial Histories: A Vision of Anthropology

from the Margins

ABSTRACT Initially given as the Presidential Address at the 100th Meeting of the AAA, this article examines the contributions of

women and minority anthropologists who have struggled to gain a place at the center of the discipline. Despite 25 years of scholarship

on women and minorities, anthropology needs to go further in terms of paying attention to their pioneering efforts and the breadth

of their scholarship. The article explores four currently important areas of creativity: (1) the transformation of field research through

problem-oriented participant observation and "native anthropology," as exemplified by George Hunt, the young Margaret Mead, and

Delmos Jones; (2) the evolution of more dialogical forms of ethnographic writing, as pursued by Elsie Clews Parsons, Gladys Reichard,

Ella Deloria, and Zora Neale Hurston; (3) sources of critique, as embodied in the work of Ruth Benedict and Michelle Rosaldo; and

(4) forms of activism, engaged in by Anita McGee, Benedict, Mead, and Alfonzo Ortiz. [Keywords: history of anthropology, women,

minorities]

IN 2002 THE AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION (AAA) celebrated its 100th anniversary. Cen-

butions of selected women and minorities connected to

them as spouses, students, colleagues, or fieldwork assis-

tennial commemorations occasion two impulses: that of

tants. These women and minority anthropologists either

celebration and that of reevaluation and critique. Our first

struggled to gain a place at the center or remained mar-

impulse is to celebrate-to invoke the important central

ginal relative to their colleagues and mentors during their

life times.

figures in our history and reflect on the dominant theories

and insights that have shaped anthropology as a set of

Each generation of anthropologists revises history,

finding in the past precursors of present-day topics of in-

methodological practices and as a body of knowledge for

understanding humankind. To this end, the AAA, in col-

tense debate and reformulation. But there is also a peda-

laboration with the University of Nebraska Press, publish-

gogical goal in rethinking our history. Whose work gets

ed Celebrating a Century of the American Anthropological As-

taught and how it is connected to other traditions is criti-

sociation: Presidential Portraits. Regna Darnell and Fred

cal to the shaping of anthropology for the next genera-

Gleach (2002) put together a fascinating series of bio-

tion. By stressing the breadth and creativity of the contri-

butions of women and minorities, we can enrich our

graphical sketches along with the presidential photos that

line the wall of our conference room at the AAA headquar-

description of what anthropology has been and continues

ters in Arlington,VA. This volume constitutes a part of our

to be.

My choice of focus reflects our current interest in

"official history."

But the aim of this article is to invoke the second im-

reshaping fieldwork, revising the way ethnography is writ-

ten, providing cultural critique, and opening pathways for

pulse-that of reevaluation and critique. As is fitting for

incorporating activism into anthropology. The figures I

an address on the eve of the AAA Centennial I will begin

have selected made contributions in each of these areas. I

with brief glimpses of several "iconic figures": AAA presi-

will look at three groups of women and minority anthro-

dents who were intellectually and institutionally at the

center of the discipline in their time. My main emphasis is

pologists: (1) elite women who entered the discipline in

the formative period between 1900-45; (2) minorities who

not, however, on these figures but, instead, on the contri-

AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST 106(1):126-139. COPYRIGHT ? 2004, AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

This content downloaded from 196.11.235.231 on Fri, 04 Mar 2016 13:30:34 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Lamphere * Presidential Address 127

were connected to anthropology in the same time period;

and (3) minorities and women who came to the very dif-

ferent institutional and intellectual milieu of anthropol-

tial number of senior women faculty, including minority

women, although perhaps not the same proportion as sen-

ior women in departments nationwide. Minority men

were beginning to achieve tenure in these departments as

ogy after 1960.

Among the representatives of the first group, I will fo-

well. It is no longer unusual for women to be directors of

cus on Elsie Clews Parsons, Ruth Benedict, and Margaret

University Museums of anthropology or chairs of anthro-

Mead: three women who arguably had the greatest impact

pology departments. The AAA itself has had eight female

on the anthropology of their time. All three were from

middle- or upper-class backgrounds, were able to gain ac-

cess to elite colleges and universities, and later became

presidents of the AAA. As such, a focus on these women

presidents, including the first female African American

president (Yolanda Moses). In terms of the institutional

representation and impact on future generations of an-

thropologists through teaching and mentoring, women

initially may not seem to constitute a "view from the mar-

and minorities are in a much stronger position than in the

gins." However, on closer examination, each was excluded

past.

To understand this generation of women and minor-

in subtle ways from important disciplinary rewards or

achieved them at a much later stage in their lives than

their male peers. Until recently, the breadth and creativity

of their work has been unacknowledged, and even today

their contributions are often "pigeonholed" in narrow

ways. Moreover, these three women were exceptions.

Most women interested in anthropology at the beginning

of the 20th century were marginalized. Women members

of the AAA were primarily amateurs without connections

to major institutions.' Some, like Anita McGee, led lives of

service outside of anthropology, combining their interest

in other cultures with activism. Three decades later, most

Ph.D. recipients were likely to find positions in museums,

government service, or small liberal arts colleges. Gladys

ity anthropologists, I focus on Michelle Zimbalist Rosaldo,

Alfonso Ortiz, and Delmos Jones, all of whom wrote at the

beginning of this sea change in the discipline. They are

part of the transformation of anthropology as it grew

larger and became increasingly influenced by the antiwar

movement, feminism, the Civil Rights movement, and

Native American activism.

In looking at all three groups, I will explore the inno-

vations in their work that have resonance with our con-

temporary preoccupations. This article will stress four

sources of creativity: (1) the transformation of field re-

search from textual transcription to problem-oriented par-

ticipant observation and native anthropology, exempli-

fied by George Hunt, the young Margaret Mead, and

Reichard represents this latter path. She remains largely

unrecognized for her scholarly work. Furthermore,

Reichard taught at the undergraduate level and, therefore,

had less influence on the graduate students who then be-

came the next generation of anthropologists.2

Delmos Jones; (2) the evolution of ethnographic writing

from the standard ethnographic present to more dialogical

forms, as seen in the writing of Elsie Clews Parsons, Gladys

Reichard, Ella Deloria, and Zora Neale Hurston; (3) sources

of critique, often emanating from a marginal positionalThe second group, late-19th- to mid-20th-century mi-

nority anthropologists (both men and women), had an

even harder time becoming institutionally central to the

discipline or having their contributions recognized in the

disciplinary canon. Many never obtained M.A. or Ph.D.

degrees. In the case of Native Americans, they were usually

relegated to being "informants" or research assistants

rather than full-fledged ethnographers and professionals.

Following the lead of many contemporary minority schol-

ity, which result in new theoretical formulations, for

which I focus on Ruth Benedict and Michelle Rosaldo; and

(4) the forms of activism both inside and outside the acad-

emy that have produced more public roles for anthropolo-

gists, as exemplified by Anita McGee, Ruth Benedict, Mar-

garet Mead, and Alfonso Ortiz.

As the AAA celebrates its Centennial, we have had 25

years of scholarship on women in anthropology.5 There

are important new collections that focus on African

ars, I wish to highlight the contributions of African Ameri-

can writers like Zora Neale Hurston and Native American

American anthropologists (Harrison and Harrison 1999;

McClaurin 2001), and there is a contined interest in the

ethnographers like George Hunt and Ella Deloria-only

three among the two or three dozen who have contributed

role of Native Americans. But the history of anthropology

and of anthropological theory is still largely portrayed in

to anthropology during the first 70 years of this century.3

Beginning in the 1960s, women entered the discipline

in increasing numbers, and more minorities (even though

they represented a small number) were recruited to the

field.

terms of the white male "founding fathers." It is disap-

pointing that new texts and readers on the history or an-

thropology pay scant attention to the work of contempo-

rary women and minority anthropologists (see, e.g.,

During the 1970s and 1980s, women still had diffi-

culty obtaining positions in the elite departments in an-

Erickson with Murphy 1991; Erickson and Murphy 2001).6

Recuperating the work of these women and minorities

needs to go beyond viewing their contributions in a narrow,

thropology.4 The AAA became the setting for an internal

conflict regarding how far a professional organization

should go in order to support the hiring and tenure of

one-dimensional fashion, such as emphasizing only the

"culture and personality" writing of Mead and Benedict,

the research on folklore conducted by Parsons, and the

women in anthropology (Sanjek 1978, 1982). By 2003,

most of the top Ph.D.-awarding departments had substan-

scholarly publications on folk tales by Zora Neale Hurston.

This content downloaded from 196.11.235.231 on Fri, 04 Mar 2016 13:30:34 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

128 American Anthropologist * Vol. 106, No. 1 * March 2004

McGee, then, is our first iconic figure, representing

Instead, the full range of their writing needs to be empha-

the Washington anthropologists and self-made men who

sized and how various genres and field experiences con-

dominated the profession at the time. He was a self-

tribute to anthropology needs to be explored. Thus

educated man of Irish heritage who grew up on an Iowa

Benedict's writing on race should be stressed in addition

farm. He became a devotee of John Wesley Powell who

to her book Patterns of Culture; Parsons's feminist book

should be mined for their contributions to ethnography;

brought him to Washington in 1883. After serving ten

and Hurston's wide range of writing (from memoir to mul-

years in the U.S. Geological Survey, McGee moved to the

tivoiced ethnography to short story and novel) should be

BAE where he became Powell's assistant and "Ethnologist-

in-Chief," running the Bureau as Powell's health declined.

part of reclaiming her as an anthropologist. Their work

McGee published widely in the fields of geology, hy-

also needs to be seen in relation to both the male figures

drology, and anthropology with over 300 articles and re-

that dominate the "official history" of the discipline and

ports, but his only field research was a few days with the

to the work of other women and minorities. We need to

more fully explore the creativity in their work that has

Seri, a group of impoverished and dispossessed Native

resonance with topics that currently are shaping the disci-

Americans living in northern Mexico. He used his meager

observations to confirm his evolutionary presuppositions

pline.

(Hinsley 1981:242). Like a number of other early presi-

My argument is not that all or even the most impor-

dents during the first 25 years who were central both insti-

tant innovations have come from those at the edges of the

tutionally and intellectually during their lives, he left little

discipline struggling to find their place at the center.

in the way of a lasting legacy. One hundred years later no

Rather, I argue that we need to go further still in terms of

one reads about McGee's elaborate evolutionary frame-

paying attention to the contributions of women and mi-

work. For someone previously central to discipline, McGee

nority anthropologists, and that by doing so we can en-

in retrospect has had little lasting impact and his career

rich our view of the past and expand our vision of future

seems like a mere footnote.

possibilities.

From a contemporary perspective, some of the women

members of the AAA who were institutionally marginal-

ized at the time appear more interesting sources of creativ-

WIDENING THE LENS: W. J. MCGEE AND HIS WIFE

ANITA NEWCOMB

ity. Women like Alice Fletcher and Zelia Nuthall were

emerging professionals, although Fletcher was blocked

from standing for a Ph.D. at Harvard. Most, however, were

part of the educated elite who took an interest in travel

and collecting, and who occasionally delivered papers at

the annual meetings. There were, however, few places for

them in the early AAA. It was a male-dominated organiza-

tion, with only 15 women among 175 founding mem-

bers.7 Excluded from the intellectual centers of the disci-

pline, women forged their contributions through activities

outside universities.

W Ai

One of the few women members of the AAA in 1902,

Anita Newcomb McGee, McGee's wife, is a case in point.

While she was marginal to the discipline at the time, her

career anticipates the kind of activist professionalism that

marks a return to public anthropology in recent years.8

WJ McGee Anita McGee

She is a fascinating example of a woman who obtained

The discipline's early years illustrate particularly well why

professional status and used it to pursue an activist role,

going beyond the institutionally central figures is neces-

following a kind of dedicated social service model preva-

sary in constructing a canon that fully reflects the richness

lent among women during the late 19th century.

of our history. Today, it is hard to imagine how small the

group of active anthropologists was at the Turn of the

During the Spanish American War, in 1898, McGee

convinced the surgeon general of the need to recruit trained

Century. At the founding meeting on June 30, 1902, 13

nurses who had not been able to serve since the Civil War.

men (seven of whom would become future presidents) se-

She started the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR)

lected the 24 members of the council, chose the nine

member executive committee, and elected the officers in-

cluding WJ McGee, the first AAA president. The first two

decades of the AAA were dominated by the Washington an-

Hospital Corps, which in 1901 became the Army Nurse

Corps. She was appointed acting assistant surgeon general,

the first woman to hold such a position. In 1904-05, she

took nine nurses who had served in the Spanish conflict to

thropologists: followers of McGee and those associated

Japan to work alongside Japanese nurses during the Russo-

with the Bureau of American Ethnology (BAE) (Darnell

Japanese War. During 2001, her photos of the trip were on

1998: ch. 13; Stocking 1968: ch. 11).

exhibit at the National Museum of Health and Medicine at

This content downloaded from 196.11.235.231 on Fri, 04 Mar 2016 13:30:34 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Lamphere * Presidential Address 129

the Walter Reid Hospital in Washington, D.C. That year

was the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Army

number of texts that were central to the kind of ethnogra-

phy Boas espoused.

Nurse Corps and recognition was being given to McGee as

Hunt did not take down stories by dictation. Instead,

its founder (Dearing 1971:464-466).

he listened to a performance and then went home and

wrote down a text. He often put together several versions

THE TRANSFORMATION OF FIELD RESEARCH: BOAS,

HUNT, AND MEAD

of the story or combined his own observations with the

information from several informants (Berman 1996:235).

This technique was acceptable in a period in which in-

tracultural variation was less recognized and fit well with

Boas's attempt to build a picture of Kwakuitl culture as a

seamless whole. There is a clear asymmetrical dynamic

,.

here. Boas controlled the subjects of the text and worked

hard to get Hunt to produce exactly what he wanted, in

\, 4 :9

some cases hinting that continued financial support rested

on Hunt's willingness to provide Boas with a continuous

flow of information.

For his part, Hunt exercised a certain amount of in-

Franz Boas George Hunt Margaret Mead

dependence and creativity even as he complied with

Boas's demands. Unlike Boas, Hunt often took the role of a

While Anita McGee is an interesting precursor of contem-

participant-observer, recording his wife's recipes, collect-

porary public anthropology, it was not until Franz Boas

ing crest stories from each Kwakuitl group, and learning to

and his students achieved preeminence in the discipline

become a shaman. His textual strategies were innovative

that women gained Ph.D.s and were able to contribute

as well. Hunt wrote in an authentic Kwakw'ala speech

more fully to both theory and ethnography. In addition,

style that was primarily used for the myth recitations, al-

minority anthropologists began to move beyond their tra-

ways writing in ways that would "show you the oldest way

ditional role as "informants." Boas is well known for his

of speaking" (Briggs and Bauman 1999:491).

commitment to a detailed scientific study of cultural phe-

What I want to highlight is Hunt's creative ability to

nomena, the creation of an integrated four-field disci-

forge a separate role as ethnographer and writer apart from

pline, and the use of a historical rather than evolutionary

Boas. As Jean Canizzo argues, "George Hunt is one of the

framework. Thus, Boas is the second institutionally central

most important originators of our current view of 'the tra-

figure I will emphasize. Here, I want to focus on George

ditional' Kwakiutl society; he is a primary contributor to

Hunt and Margaret Mead and the ways they transformed

the invention of the Kwakiutl as an ethnographic entity"

Boas's approach to field research. When each began work-

(Canizzo 1983:45). Without him, our sense of the tradiing with Boas, they were both marginal but for very differ-

tions, stories, and practices of this group of Native Amerient reasons: Hunt's marginality was embedded in the co-

cans would be very much diminished.

lonial context where anthropologists found themselves

Mead took Hunt's explorations in fieldwork methodol-

working with Native intellectuals who were on the edges

ogy one step further, enlarging the role of participant obserof Indian communities; meanwhile, Mead was institution-

vation and breaking with Boas's tradition of holistic eth-

ally marginal simply because she was a student and only

nography. Boas had always been in the habit of giving

24 years old. However, both managed to transcend their

problems to his students for study. So when Mead insisted

positions. Mead circumvented the control of her much

on going to Samoa, he set out for her the problem of adoolder mentor, Boas, and in a "gutsy move" went to Samoa

lescence. Taking Boas's directions as a starting point, she

and created new forms of fieldwork. Later, she was able to

shaped her own problem-focused methodology.

leverage the advantages of her class and the gender per-

Mead spent six months studying 68 girls between the

missiveness of the interwar period to project herself into

the center of anthropology. Hunt faced more difficult ob-

ages of nine and 20 who were residents of three contigu-

ous villages on the tiny island of Tau in American Samoa.

stacles; however, he was able to create a role as "intercul-

The appendices and text of Coming of Age in Samoa indi-

tural interlocutor."

cate that Mead gathered copious amounts of information

Boas first met Hunt in 1886 during his first field trip

to the Kwakiutl.9 The son of a Scots-Irish Ft. Rupert trader

and Tlingit mother, Hunt was not a Kwakiutl but grew up

learning the Kwakw'ala language as well as English. His

position was one of an outsider on the inside. Over 45

years, Boas conducted only about 15 months of field re-

search among the Kwakiutl. Once Boas taught Hunt how

to write Kwakw'ala, it was primarily the correspondence

on these young girls (Mead 1961:249-265, 282-294). Her

chapters include portraits of several girls with comments

on their relations with parents and siblings, their standing

in the community, and their experience with boys. In ad-

dition, she gave each girl a battery of tests in the Samoan

language. Mead credits herself with inventing a cross-

sectional method of studying girls at different stages of pu-

between Hunt and Boas that created the monumental

berty in order to get at a process-that of acquiring and

This content downloaded from 196.11.235.231 on Fri, 04 Mar 2016 13:30:34 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

130 American Anthropologist * Vol. 106, No. 1 * March 2004

performing the requisite adult gender roles of a culture

(Mead 1972:154).

opening up for anthropologists in universities and col-

leges, but women still had difficulty getting them. Finan-

Much has been made of Mead's "wind in the palm

trees" method of ethnographic writing: her exotic descrip-

tions that represent a general picture with ideal-typical

specifics but no individual people. However, a close read-

ing of Coming of Age in Samoa shows that she paid special

attention to individual cases (Lutkehaus 1995:186-206).

She presented several kinds of behavior to be found

cial security or being married mattered; either or both

could be used to disqualify women from being considered

for positions in elite departments. Parsons came from a

wealthy New York background and used her money to

support Columbia's anthropology department, fund re-

search in the Southwest, and finance several anthropologi-

cal publications. As a married woman with four children,

among the "typical" girls in her study, as well as in exten-

three homes, and a number of servants, she was in a posi-

sive examples of "the girl in conflict" (see Mead 1961: chs.

tion not to need an academic appointment (Deacon

10 and 11). Contrasted with the text-based field research

of Boas and Hunt, Mead's innovative methodology reflects

1997). However, this kept her from influencing the next

generation of anthropologists. This structural marginality

a whole new chapter in fieldwork.

allowed for the erasure of many of the contributions that

NEW FORMS OF ETHNOGRAPHIC WRITING: KROEBER,

before WWII. A sort of disciplinary amnesia developed

Parsons and other white women made to anthropology

PARSONS, AND REICHARD

about these contributions, allowing James Clifford to

write in his introduction to Writing Culture that feminist

ethnography "had not produced ... unconventional forms

of writing" (Clifford 1986:21).

Parsons was the same age as Kroeber. They were

friends, working partners, and, possibly, intimates. Kroe-

ber and Parsons first met at the end of a second brief field

trip to Zuni in December 1915. Her psychological ap-

proach to culture highlighted the interplay between social

constraint and individual psychology in contrast to Kroe-

ber's emphasis on a culture as superorganic. They devel-

Alfred Kroeber Elsie Clews Parsons Gladys Reichard

oped a close friendship, all the while teasing each other

about their theoretical differences. Kroeber spent two weeks

Alfred Kroeber is the third iconic figure I treat here, and

at Parsons's Lounsberry Estate (outside New York City)

the most prominent U.S. anthropologist after Boas. He be-

during May 1918. They then shared a three-week field trip

gan his two-year term as president of the AAA in 1917 at

to Zuni in September. Correspondence suggests to that al-

the young age of 41. While president of the AAA, Kroeber

though their time in New York was filled with long walks,

published "The Superorganic" (1917), his initial and most

stimulating conversation, and mutual work, the Zuni trip

important statement arguing that culture should be

was disappointing. Parsons felt subordinated to Kroeber's

treated sui generis as a separate level of analysis, distinct

interests and lacked the space and time to achieve her own

from the biological or organic. On the one hand, Kroeber's

goals (Deacon 1997:207). Their relationship afterward be-

work can be seen as a codification of Boas's approach. On

came more distant, although still a genuine friendship.

the other, it is evident that he advanced our thinking

Kroeber returned to California and his career at the center

about the nature of culture, developing the concepts of

of the discipline, while Parsons continued her work as eth-

pattern and configuration and utilizing them to analyze

nographer, folklorist, and patron.

the history of a wide number of cultures and civilizations.

Parsons began her innovative writing style through a

During the 1920s and 1930s, when Kroeber's vision of

series of feminist books that combine trenchant social cri-

anthropology with its emphasis of trait distributions and

tique with cross-cultural ethnographic analysis. Books like

configurations dominated the discipline, two women-El-

the Old-Fashioned Woman (1913) and Fear and Convention-

sie Clews Parsons and Gladys Reichard-created open and

ality (1997) blend insightful ethnographic commentary on

innovative styles of ethnographic writing, 50 to 60 years

before new forms of dialogical text-making came into

vogue. Although both were committed to the Boasian tra-

dition in terms of their theoretical writing, they used eth-

nography in new ways. These innovations went long un-

recognized as these women worked in the shadow of

her own upper-class social circle with examples from a

wide range of other cultures. When Parsons turned to an-

thropology, she continued to be interested in the position

of women and published a series of articles between

1915-24 on Pueblo women, including their roles as moth-

ers. These essays are more open and dialogic than either

Kroeber, Robert H. Lowie, and other prominent male stuher previous writing or the ethnographic texts of Boas and

dents of Boas during this period.

Hunt. They rarely use cross-cultural comparison, social cri-

The situation of Parsons and Reichard points to the

tique, or irony. Instead Parsons adopted what Barbara Bab-

subtle ways that even elite white women were structurally

marginalized. During the 1920s and 1930s, positions were

cock describes as "a polyphonic pastiche that mixes styles

and genres, invoking, questioning, and comparing the

This content downloaded from 196.11.235.231 on Fri, 04 Mar 2016 13:30:34 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Lamphere * Presidential Address 131

voices and authority of other anthropologists as well as

her own previous inscriptions of Pueblo life" (Babcock

scribes the scene when Red Point finds out about the inci-

dent:

1991:16). Her ethnography is a blend of different points of

Red Point was so excited last evening about the Navajo

view: the anthropologist as observer, the native "other"

boys taking pay for helping us that he did not think of

answering the anthropologist's questions, transcriptions

anything else. Today, as Marie is stringing the new blan-

of ritual texts, and narratives from Pueblo women them-

ket over the temporary frame and as I unwind the yarn

from the skein, preparatory to winding the ball, he comes

selves. For example, in an article on "Mothers and Chil-

in. He is in his usual mild temper, but cannot refrain from

dren at Laguna," Parsons gives her hostess Wana's narra-

mild remonstrance. "Too bad you paid that money. You

tive of the naming ceremony used for her two-week-old

wouldn't have had to do it if I had been here." He has

baby. It includes Wana's drawing of the altar and a text of

come to see my first blanket. As I spread it out I tell him

the medicine man's prayer in both Keres and English (Par-

that at Ganado they all laughed at it. Whereupon he leaps

sons 1919:34-38). More examples of this dialogical weavto my defense with, "Tell them to make one." [Reichard

ing of Parsons' voice, as well as that of her subjects, can be

1934:60]

found in her other articles on Pueblo women and in her

Although Reichard describes Red Point's emotions in

later work on Mexico. Parsons' work clearly anticipates the

her own words, she gives her subject a voice and presents

kinds of textual strategies that ethnographers have been

much of the conversation in his words. In addition,

employing in the last two decades as anthropologists have

Reichard places herself within the text, making it more

gone beyond the position of the distant observer, writing

dialogical and exploring the nature of their interaction, as

in the third person and using the "ethnographic present"

well as her own views and behavior. Throughout the book,

that was typical of many classic ethnographies.

Reichard's descriptions of the Southwest, her nights under

However, in terms of influencing students, colleagues,

the stars, and the sunsets are quite evocative. Rather than

and anthropological institutions, Parsons remained struc-

giving us analytic concepts (such as the centrality of genturally marginal and was only fully recognized when she

erosity and reciprocity), we get a better sense of the indiwas elected AAA president in 1941 at age 73. She died be-

viduality of Navajo actors and Reichard's own views. Defore she was able to give her presidential address, which

was delivered instead by Gladys Reichard. It has only been

signed for a popular audience but employing surprisingly

modern textual strategies, the book portrays the "feel" of

in the last 15 years that Parson's feminism has been redis-

Navajo life, something rarely found in ethnographies of

covered and an appreciation for her textual innovations

the period.

developed (Babcock 1991; Deacon 1997; Lamphere 1989;

Her second innovative book, Dezba: Woman of the DeZumwalt 1992).

sert (1939), is a novelistic account of Navajo life based on

Gladys Reichard, who saw Parsons as her mentor, car-

ried these textual innovations even further. Her research

trips to the Navajo reservation during the summers of

1930-34 were funded by Parsons through her Southwest

society. She stayed with Red Point, a well-known Navajo

singer and his extended family. Reichard was interested in

crafts and decided that "learning to weave would be a way

of developing the trust of the women" (Reichard n.d.:l).

Reichard's experiences during her three summers with Red

Point's family. Reichard uses several textual strategies:

conveying the Navajo ceremonial system as a set of inner

beliefs held by Desba; employing careful ethnographic ob-

servations to create fictional descriptions of a sheep-dip

and the Navajo girl's puberty ceremony; using plot devices

to explore the internal dynamics of an extended family in

Living with a Navajo family allowed Reichard to see

a matrilineal society; and creating situations that reveal

Navajo social life from the inside. The fact that she was a

the impact of Anglo society on Navajo culture. In Dezba,

woman helped her to obtain a sense of the internal core of

Navajo kinship: a mother and her children. She published

her experiences in two books: The first, Spider Woman

(1934), is an ethnography and personal memoir; the sec-

ond, Dezba: Woman of the Desert (1939), is a novel.

Spider Woman is a long and complex dialogic text full

of more extensive innovations as compared with Parsons's

articles. It contains more of the research process, elabo-

Reichard takes a woman's point of view. Yet, in doing so,

she also gives readers a sense of the variety of male and fe-

male individual personalities found within a family as

well as a window into how Navajo life was changing in the

1930s.

Like Parsons, Reichard's position as a woman shaped

her career trajectory and her legacy. Boas gave his position

at Barnard to Reichard, who was single and needed to sup-

rates on the interaction between ethnographer and subport herself, passing over Ruth Benedict, who was married

ject, and records conversations as well as descriptions. Al-

at the time. Although her teaching position at an elite

though Reichard does the recording and much of the

women's college provided Reichard with a secure life, it

interpreting, the voices of Red Point's family are heard as

also limited her influence over graduate students in a pe-

well. For example, one afternoon Reichard paid several

riod when training the next generation of anthropologists

Navajo boys for helping pull her car out the mud. She de-

was taking on more importance (Lamphere 1993:178).

This content downloaded from 196.11.235.231 on Fri, 04 Mar 2016 13:30:34 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

132 American Anthropologist * Vol. 106, No. 1 * March 2004

without taking shorthand notes. She simply listened to

EXTENDING NEW FORMS OF ETHNOGRAPHIC TEXT

stories and later wrote them down as she remembered

MAKING: HURSTON AND DELORIA

them, first in Lakota and then in English (Rice 1992:5). In

her writing she attempted to convey an oral tradition with

subtle linguistic features such as exclamations or com-

pound words. Her transcriptions supplied the emotion,

ElD

humor, or irony that many folklorists have felt only an

oral performance could convey (Rice 1993:14). Rice likens

her work to that of Nobel Prize winner and Yiddish novel-

ist Isaac Bashevis Singer: Both pioneered a new multilin-

gual literature, writing or collecting texts in their native

languages and publishing them in both languages (Rice

1992:6).

After Boas died in 1942, Deloria continued to innovate

in the ways she wrote about Dakota culture. Her work,

both as a social analyst and as a novelist, can be thought

of as an example of writing for the public.10 In 1944 she

produced Speaking of Indians, which was written for mis-

Ella Deloria Zora Neale Hurston

sionaries and others who had preconceived ideas that the

Reichard and Parsons were not the only female anthro-

Dakota no longer had a culture of their own with its own

pologists who wrote experimental texts in the in the

kinship system, social organization, religion, or set of val-

1920s and 1930s. During this period some minority

ues. Deloria felt that these people tried to "pour white cul-

women were obtaining college educations, though only a

ture into a vacuum and when that did not work out, they

few were able to study at elite institutions like Columbia

concluded that the Indians were impossible to change and

and Barnard. Ella DeLoria and Zora Neale Hurston were

train" (DeMallie 1968:238). Her book emphasized the im-

among these women. Both were mentored by Boas, colportance of Dakota kinship and the value of sharing. It

lected folk tales, and experimented with new literary

also discussed the obstacles facing the Sioux after they

forms: the memoir, the novel, and books for popular read-

were relocated to reservations (Deloria 1944:48-87).

ership.

At the same time, and with the support of Benedict,

During her lifetime, Ella Deloria explored a wider

Deloria finished the novel Waterlily, which at the time

range of genres than Reichard, working carefully in her

went unpublished because of a lack of interest in a book

native language and writing for the public but also, like

focusing on Dakota women. In the book, Deloria por-

Reichard, using ethnographic accounts in fictional texts.

trayed Dakota culture through the eyes of the female char-

Born on the Yankton Sioux reservation, her great-grandfaacters, a careful reconstruction of life in the camp circle

ther was a powerful medicine man and her father an Episduring the late 19th century, based on the descriptions

copal priest. As a child, Deloria learned to speak all three

she collected from elderly informants. In 1988 the Univer-

dialects of Dakota but was educated in Episcopal schools.

sity of Nebraska finally issued Waterlily. In evaluating the

She received scholarships to Oberlin and then to Columscope of Deloria's contributions, Bea Medicine noted,

bia Teachers' College. It was at Columbia that she met

Deloria's body of work remains among the fullest ac-

Boas, and he asked her to help translate a collection of

counts of the Dakota culture in the native language. It is

Lakota stories. She received a B.S. degree in 1915 and reunique as a woman's perspective, which has been lacking

turned to South Dakota to take care of members of her

in the writings on the Lakota/Dakota/Nakota peoples, and

as an interpretation of the Dakota reality to other peoples.

family. Boas lost track of her until 1927 when he met her

[Medicine 1988:49]

at the Haskell Institute where she had accepted a job as a

physical education instructor. In 1928 he brought her to

Perhaps the most innovative textual strategies were

New York to work on the translations of Dakota texts (Dethose of Zora Neale Hurston, who has only recently been

Maillie 1988:235). Over a period of 15 years, whether livrecognized for her creative contributions to anthropology.

ing in South Dakota or on brief trips to New York, she as-

sisted Boas in publishing a Sioux grammar (Deloria 1941)

and a Sioux-English dictionary. She also translated and

transcribed an enormous body of texts, many of which

she collected herself. Julian Rice, an English professor and

Born in 1894, Hurston grew up in Eatonville, Florida, a

self-governing, African American town with a rich folk tra-

dition. Hurston's years in Eatonville, followed by a decade

of struggling to support herself and pursue an education,

imbued Hurston with a strong will, a firm sense of her

literary scholar who has worked intensively with Lakota

own independence, and ardent racial pride, as well as a

materials, has reprinted, annotated, and interpreted many

gift for storytelling, irony, and humor. The stories that

of Deloria's texts. He argues that Deloria should be viewed

laced her books were often ones she had honed in "per-

as a literary creator rather than scrupulous recorder in the

formances" at parties. As Langston Hughes noted, "Only

Boasian sense (Rice 1992:1-20). Like Hunt, she worked

to reach a wider audience, need she ever write books, be-

This content downloaded from 196.11.235.231 on Fri, 04 Mar 2016 13:30:34 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Lamphere * Presidential Address 133

cause she is a perfect book of entertainment in herself"

most anthropologists. Graciela Hernandez describes Hur-

ston's ability to cultivate subjective and objective voices

(Boyd 2003:140).

Hurston arrived in New York in 1925 when she was 31

years old with a high school diploma from Morgan Acad-

throughout her work as embodying "a literary harmonic"

(Hernandez 1995:156).

Race and class shaped both women's marginality and

emy and three years of course work from Howard Univer-

added the dimension of financial dependence to their re-

sity. Within nine months, she had become recognized as a

writer and accepted as the first Black student at Barnard

lationships to their patrons-for Deloria, Boas, and for

Hurston, both Boas and Mason. In Deloria's case, her obliCollege. During the next few years she was part of two

contrasting worlds: Harlem with its circle of young black

writers and artists and Barnard with its students and fac-

ulty. She attended "rent parties" in Harlem (where atten-

gations within the Dakota kinship system were always a

source of tension. In a poignant letter to Boas, Deloria ex-

plained,

dees contributed up to 50 cents to help the host defray the

Now, as regards my returning to New York. I have never

high cost of rents in segregated Harlem); participated in

told [sic] this, but besides my nieces and nephews for

whom I am guardian, I am responsible perfect for provid-

upscale dinners hosted by white patrons at New York res-

ing the roof for my sister as well as for me.... If I were

taurants; and visited the homes of her Barnard classmates.

alone in the world, I might risk it; but with things as they

She won competitions for her short stories and collabo-

stand, I am afraid to return to New York, so far from the

rated on Fire!, a short-lived journal that included contribureservation, for so little money. [Deloria in Finn 1995:139]

tions by the best young writers and artists of the Harlem

When Boas was unable to provide funds, she was forced to

Renaissance.

sell her trust land and derive limited income from speakWhile at Barnard, she first took a course from Reichard

and then came to the attention of Boas (Hurston 1996:

ing engagements and short-term teaching jobs.

Hurston was acutely aware of her unusual position as

140). Boas reportedly sent her out to measure heads in

Harlem (Boyd 2003:114) but also encouraged her to study

a young African American woman at Barnard. In her

memoir Dust Tracks on the Road, she included this pithy

folklore. After her graduation in early 1927, Boas arranged

statement, "The Social Register crowd at Barnard soon took

a fellowship for her to return to Eatonville and other parts

me in and I became Barnard's sacred black cow" (Hurston

of the South to collect songs, stories, jokes, and dances.

1996:139). Hurston had a complex relationship with Ma-

Charlotte Osgood Mason, a wealthy white patron who

son, who demanded she work in secret and accept Ma-

supported a number of Black writers including Langston

son's vision of Negro "primitiveness." On the one hand,

Hughes, funded a second, longer trip. Hurston's book

she chafed at the restrictions her patron placed on her

Mules and Men (Hurston 1990a) is part ethnography, part

work (Boyd 2003:171-174). On the other hand, she wrote

folklore collection, and part novelistic account of two

adoring letters to her, addressing her as "Godmother" and

years in the South. Written in dialect, Hurston's book is a

tale framing other tales. Her entrance into Eatonville is

full of dialogue as she tries to position herself as Zora re-

signing them "Most devotedly," or even "Your Pickaninny"

(Kaplan 2002:211-212, 216-219). Boyd argues that much

of this flattery was "tongue-in-cheek" and that Hurston

turned home-just Lucy Hurston's daughter instead of

"knew how to play the wealthy widow like the guitar"

some rich Northerner with a Chevrolet. The stories are not

set apart as some dry-as-dust texts but are fully integrated

(Boyd 2003:195). By 1932, Hurston had begun to wean

herself financially from Mason.

into the situations in which people recount them. On her

In the most discouraging incident, Hurston's Rosen-

first day, the stories are interrupted when Eatonville folks

wald Fellowship, awarded so she could complete a Ph.D. at

decide to take in a party in nearby Woodbridge, convinc-

Columbia University, was shortened to only one semester

ing Zora to give them a ride in her fancy car. Later when

when the director rejected her proposed plan of study.

she ventures into Polk county and attends a dance near

one of the local sawmills, she is first seen as a stranger

Disappointed, Hurston left graduate school at the end of

the semester. Hurston won acclaim as a novelist and ethwearing a very expensive ($12.95) Macy's dress. She deftly

nographer during the mid-1930s, but she also struggled finegotiates an acceptable identity for herself among the

nancially. Though she faced discrimination in the Jim

men gathered at the fire outside the dance. In the follow-

Crow South, she never acknowledged this: "Hurston was

ing days, a number tell her stories of "the Massa and John"

not deaf, dumb, and blind to the facts of American racism.

amidst lively conversation.

But she had long ago made a decision that was reflected in

A second ethnographic work, Tell My Horse (1990b),

her own autobiography. She would not allow it to define

was based on field research in Jamaica and Haiti and

or distort her life" (Boyd 2003:359). Her later years were

funded by a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1934-35. Like

characterized by illness, isolation, and financial problems.

Mules and Men, it contains rich ethnographic descriptions

In 1960, shortly after she was confined to a nursing home,

with Hurston as a prominent force in both ongoing inter-

Hurston died in Ft. Pierce, Florida, and was buried in an

action and in particular conversations. Her ear for dia-

unmarked grave.

logue, her novelist's attention to detail and character, and

The rediscovery of both Deloria and Hurston owes as

her belief in the richness of black culture allowed her to

much to those outside of anthropology as to those within

create ethnographic descriptions that were unequaled by

This content downloaded from 196.11.235.231 on Fri, 04 Mar 2016 13:30:34 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

134 American Anthropologist * Vol. 106, No. 1 * March 2004

the discipline. Literary scholar Julian Rice has republished

a feminism that deeply offended the conservative Sapir,

Deloria's Dakota texts with ethnographic and historical

they became more distant (Handler 1986:145-147).

commentary (Rice 1992, 1993), while anthropologist Bea

Sapir's career makes a compelling contrast to Benedict's

since the comparison points to the difficulties women had

Medicine has been the crucial voice reminding us of De-

in gaining a foothold in central institutions and building a

loria's innovations (Medicine 1988). African American

lasting legacy within the discipline. Although nearly the

feminists, particularly Alice Walker, made Hurston an

same age as Sapir, Benedict came to anthropology later in

early literary heroine of "African American memoir as fic-

life-at the end of her marriage. Boas worked for several

tion" (Walker 1975). Black feminists within anthropology

years to obtain an appointment for her at Columbia, but

have added to the depth of our knowledge of Hurston's

the dean of Graduate Studies refused the request. Only in

work, claiming her as an anthropological foremother

1931, when a new dean was appointed, was Boas able to

(McClaurin 2001; Mikell 1991).

secure an assistant professorship for Benedict (Caffrey

1989:113-114). However, six years later she was passed

CRITIQUE FROM THE INSIDE: SAPIR AND BENEDICT

over as department chair in favor of Ralph Linton because

the university administration would not allow a woman

in that position, even though Benedict had been acting

head at several points during the Boas years. She was not

elected AAA president until 1947 and then served only six

months because a new AAA constitution was taking effect

E St

and she declined to run for reelection. Finally, Benedict

was promoted to full professor only a few months before

her death in 1948.

These career difficulties may have added to Benedict's

\ /.

view of herself as marginal to U.S. society. Her early deaf-

ness, her commitment to loving women, and her discom-

fort with the way women's professional roles were con-

strained contributed to her feelings of marginality and

isolation. Benedict, of all women anthropologists in the

Edward Sapir Ruth Benedict

United States, went furthest in terms of penetrating the

"center" of the discipline: She held a tenured position in a

prestigious department, wrote and published popular and

I invoke Edward Sapir as the next iconic figure because he

theoretically important books, influenced a number of

was just as important as Kroeber in carrying on Boasian

students, and is acknowledged in current books on an-

anthropology and was very much at the center of develop-

thropological theory for her contributions.

ments in linguistics and culture and personality, two im-

Only recently has renewed interest in Benedict allowed

portant aspects of U.S. anthropology during the 1920s and

us to see the barriers within her career and the broader

1930s. He served as President of AAA in 1938, by which

scope of her anthropology. Feminists have provided many

time membership had grown from the 500 of Kroeber's day

crucial biographies of Benedict (Caffrey 1989; Modell

to 1,000. Sapir was a brilliant linguist who devoted much

1983) and have revised our notions of her contributions to

of his life to the study of Native American languages. His

theory. While most anthropologists have viewed Benedict

early monograph on Time Perspective in Aboriginal Ameri-

merely as a member of the "culture and personality

can Culture, a Study in Method (1916) was a typical Boasian

school" and have criticized her treatment of cultural patterns

text. Beginning with his critique of Kroeber's idea of the

(such those elaborated by the megalomaniac Kwakuitl) as

superorganic (1917), Sapir turned his attention to the rela-

examples of "personality writ large," Babcock takes a new

tionship between the individual and culture, the concept

approach. She sees Benedict as someone who was deeply

of personality, and the notion of "genuine culture" (Sapir

influenced by literary and philosophical traditions and

1924). These writings and his contributions to linguistics

whose work is a precursor to recent interpretative and

made him one of the most influential anthropologists of

postmodern anthropology (Babcock 1993). In a continued

his generation and earned him appointments at both the

effort to broaden our view of Benedict's contributions, I

University of Chicago (1925-31) and Yale (1931-38).

stress the critical stance that Benedict took within her

Sapir had intense relationships with both Mead and

theoretical work about culture, the individual, and race,

Benedict during the 1920s."1 Sapir and Benedict had both

and the way in which she took a public stance on some of

faced traumatic personal experiences-Sapir's first wife

the important issues of her day, this latter approach often

died and Benedict was estranged from her husband-and

they encouraged each other in writing poetry to cope with

these difficulties. Then when it became clear that Benedict

was committed to a professional life and began to exhibit

associated with Mead rather than Benedict.

The last chapter of Patterns of Culture (Bateson 1934) is

devoted to the relationship between culture and the indi-

vidual. Benedict argued that individuals shape their lives

This content downloaded from 196.11.235.231 on Fri, 04 Mar 2016 13:30:34 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Lamphere * Presidential Address 135

in terms of the cultural patterns that they are given. How-

ever, not all individuals fit into the dominant patterns and

these individuals are seen as deviants. Benedict argued for

the tradition developed by Benedict and Boas, Mead had

become a powerful spokesperson for anthropology outside

of the discipline. She wrote a column for Redbook Magazine

a relativist notion of deviance and its opposite "normal-

and lectured extensively on a wide variety of contempo-

ity." Using the example of homosexuality, she suggested

that, although in Western cultures homosexuality was re-

rary issues. But, in her role as a public intellectual and ad-

vocate, Mead was regarded with some ambivalence in the

garded as a perversion, in other cultures-for example, in

profession (Lutkehaus in press). She was never appointed

ancient Greece and among the Pueblos of the South-

as a full-time tenured member of the Columbia anthropol-

west-it had a valued place. She recommended more huogy department, and her office in the corner tower of the

mane ways of dealing with homosexuality in our own culAmerican Museum of Natural History illustrated her isola-

ture. Benedict's position was one of combining theory

tion from her colleagues and the university.

with cultural critique: an analysis of deviance but also an

By 1969, when Cora DuBois was elected president,

evaluation of how our own society might change (1934:

AAA membership had doubled, encompassing a new total

262-265).

of 5,047-including 1,520 fellows with voting rights. Un-

In the late 1930s, during the Nazi rise to power in Gerder Dubois's leadership, the AAA was reorganized to ad-

many, Benedict began to follow in Boas's footsteps and

dress the dissatisfaction of the younger generation regard-

take an active role in combating racism. While on sabbatical

ing the lack of a sufficient voice in the association. The

in California just after the outbreak of the war in Europe,

AAA Constitution was amended so that Fellows and all

Benedict wrote Race: Science and Politics (1940). The book is a

members-including students-could vote for officers of

clear, well-written discussion of anthropological data that

the association and on other issues of interest. By 1969,

discredits the notion that race is biologically based. The

the AAA had entered the era of lengthy business meetings.

last half of the book includes an analysis of racism and an

That year, the last of those meetings concluded at 1:30

examination of the persistence of racial prejudice.

a.m. on Sunday after passing 17 resolutions on topics as

Benedict worked with Gene Weltfish to produce a pam-

diverse as the recruitment of women and minorities, con-

phlet called "The Races of Mankind" (1953), which was to

demning clandestine research, and asking the AAA to take

be distributed to the YMCA. Using maps and charts, it out-

steps to end the discrimination of women. These resolu-

lined most of the material from Race: Science and Politics. A

tions reflected on a wide number issues of contemporary

furor developed over the pamphlet when Representative

and growing impact of the civil rights movement, the

Andrew May of Kentucky challenged it as a piece of Com-

feminist movement, and the antiwar movement on the

munist propaganda. The resulting publicity made the book

discipline.

an enormously popular and it received widespread distri-

Michelle Rosaldo, Alfonso Ortiz, and Delmos Jones

bution (Caffrey 1989:298-299). In evaluating Benedict, it is

represent anthropologists affected by these social move-

important not only to rethink her theory but also to see

ments. Their creativity and innovations stem from their

her as fully engaged in cultural critique and in bringing

ability to take a critical stance based on their social loca-

anthropological insights to bear on important public issues.

tion and bring it to bear on their field research, theory,

and activism. In Rosaldo's case, I will emphasize her theo-

BRINGING THE MARGINS TO THE CENTER: ROSALDO,

retical insights; with Ortiz, I will stress his less-known ac-

ORTIZ, AND JONES

tivism; and in the case of Jones, I will focus on his creative

approach to the politics of fieldwork.

Rosaldo was one of the pioneering young feminist an-

thropologists who helped revive the discipline's interest in

women. Her contributions to Women, Culture and Society

Lel

(Rosaldo and Lamphere 1974), a collection I coedited with

Rosaldo, developed out of her participation in the early

1970s women's movement. For Rosaldo, theory had a

critical role in political change. As we wrote in our intro-

duction, "Along with many women today we are trying to

Michelle Rosaldo Alfonso Ortiz Delrnos Jones

understand our position and to change it. We have be-

come increasingly aware of the sexual inequalities in eco-

Twelve years passed between Benedict's presidency and

nomic, social and political institutions and are seeking

another woman being elected to the position. In 1960,

ways to fight them" (Rosaldo and Lamphere 1974:1).

Mead became the third woman president of the AAA.

Later, Rosaldo argued that new theoretical frameworks

Mead's career makes an interesting bridge to the late

were necessary because "what we know is constrained by

1960s-a time of transformation for the AAA and in acainterpretive frameworks, which of course, limit our think-

demia as a whole. By this time the association had a mem-

bership of 800 fellows and 2,000 members. Continuing in

ing; what we can know will be determined by what we

think" (Rosaldo 1980:390).

This content downloaded from 196.11.235.231 on Fri, 04 Mar 2016 13:30:34 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

136 American Anthropologist * Vol. 106, No. 1 * March 2004

Her initial contribution to feminist theory was to pro-

vide a structuralist model of the universal asymmetry in

cultural evaluations of the sexes. She posited an opposi-

tion between the domestic and public spheres and argued

critique the neutrality of social science research. Through

his studies, Jones came to acknowledge that descriptive

studies of the hill peoples in Thailand (even those not

funded by the CIA or the Department of Defense) could be

that women's economic and political responsibilities are

unwitting tools in a counterinsurgency policy that was

constrained by childcare, while men are free to build those

aimed at keeping hill tribes loyal to their government in a

"broader associations we call society" (Rosaldo 1974:24).

She also envisioned the bases of a more egalitarian society:

system that marginalized and denigrated them. In order to

protect the Lahu families from a politically dangerous situ-

not just in the incorporation of women into the public

ation, Jones decided not to publish his research (1971).

sphere but also the corresponding incorporation of men

His classic article, "Towards a Native Anthropology"

into the domestic sphere with equal responsibilities for

(1970), contrasts his role as an "outside anthropologist" in

child rearing and domestic tasks (Rosaldo 1974).

Thailand with his role as an "insider" when conducting Den-

In the years after the publication of Women, Culture

ver, Colorado, research in the African American commu-

and Society, Rosaldo went on to make important contribunity. It set the stage for a reanalysis of field research in the

tions to the understanding of the self and emotion. But

1980s. Along with Black and Latino feminists, Jones

she also began to reconceptualize her approach to women's

viewed the role of "anthropologist" as always socially po-

roles. Although she continued to argue that the evidence

sitioned in terms of his or her class, race, gender, national-

supported the view that women have been universally

ity and sexual orientation, and the practice of anthropo-

subordinated to men throughout history and for the use-

logical knowledge as always partial and fragmentary.

fulness of the domestic-public dichotomy, she came to

Furthermore, Jones was acutely aware of how often an-

understand that this was a Western category and part of

thropologists are in a position of power in relation to their

our Victorian heritage. In her work with Jane Collier on

subjects. Yet his vision of a native anthropology opened

Politics and Gender in Simple Societies (Collier and Rosaldo

the way for establishing more collaborative relations be-

1981), Rosaldo was concerned "to stress not the activities

tween anthropologists (both insiders and outsiders) and

of women-or of men-alone" but their interdependence

communities.

(Rosaldo 1980:414). At the end of her life she was already

leading feminists to emphasize gender, the approach that

CONCLUSION

characterizes current feminist theory, and she was formu-

This address has focused on the creativity of women and

lating a sense of how to reflexively interrogate anthropo-

both male and female minority anthropologists who have

logical categories, a hallmark of postmodern approaches

come from the margins of the discipline to contribute inthat emerged much later.

Alfonso Ortiz is best known for his book The Tewa

novations and whose importance is only now beginning

to be fully recognized. The anthropologists I have profiled

World (1969), an in-depth analysis of the structure in sym-

have contributed important methodological or textual inbolic associations of Eastern Pueblo dual organization. Un-

like Rosaldo, he separated his anthropological work from

novations, theoretical insights, strategies for presenting

anthropology to the public, and new paths to activism. In

his activism, which he always insisted would be his more

many ways this work anticipated the theoretical and

lasting contribution. Ortiz's activism began in his under-

methodological trends that have been so important in regraduate days with the Southwestern Indian Regional

cent years.

Youth Council and continued during the 1970s on the Na-

tional Indian Youth Council in Albuquerque. For almost

twenty-five years, he served on the Board of the Associa-

tion of American Indian Affairs, acting as president be-

tween 1973-88. During this time, he became an eloquent

spokesperson for the American Indian Child Welfare Act

and he played a major role in the return of the sacred Blue

Lake to the Toas Pueblo. He was instrumental in the crea-

tion of the Tonto Apache Indian reservation near Payson

I have taken an integrated approach examining the re-

lationships these anthropologists had with figures tradi-

tionally seen as more central to the discipline. These rela-

tions have ranged from mentorship to ambivalent

relations of power and dependence and from collegial

friendship and intimacy to later distance. In all these con-

texts, both women and minorities were marginal to and in

the shadow of more institutionally central males. Since

Arizona. Ortiz was not someone who engaged in confron-

the 1960s mentors and patrons have become more dis-

tational politics; rather, he worked through institutions

persed as the Ph.D. programs producing women and mi-

and to use the scholarly knowledge to benefit local com-

munities (Basso 1997).

nority anthropologists have expanded. I have focused in-

stead on the impact of social movements in shaping the

Delmos Jones was one of the leading anthropologists

of the late 1960s and 1970s who began to reconceptualize

contributions of more recent women and minority schol-

ars. I have also contrasted the contributions of women

fieldwork and turn away from the notion of "pure re-

and minority anthropologists across time periods and po-

search" that motivated Boas, Mead, and succeeding gen-

sitionalities. We see, for example, a long trajectory of ac-

erations. His research among the Lahu, a hill tribe in Thai-

tivism and public commentary on critical social issues

land at the beginning of the Vietnam War, led him to

running from McGee through Ortiz (both active in organi-

This content downloaded from 196.11.235.231 on Fri, 04 Mar 2016 13:30:34 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Lamphere * Presidential Address 137

zations outside the discipline), and from Parsons to

by permission from the Dakota Indian Foundation; the

Benedict and Mead (whose roles as public intellectuals

were quite different from each other). Innovation in field-

work and ethnographic writing came from both women

and minorities, but class, race, and gender had a very dif-

photo of George Hunt was used by permission from the

American Museum of Natural History Library (negative

#11854); the photo of Zora Neale Hurston was used by per-

mission from the Van Vechten Trust (Carl Van Vechten,

ferent impact on the kinds of innovations each anthrophotographer); the photo of Delmos Jones was used by

pologist forged.

permission from Mary Lou Jones; the photo of Anita McGee

In the last two decades a generation of scholars has

was used by permission from the National Museum of

worked to recuperate these and other less well-known anHealth and Medicine (Otis Historical Archives); the photo

thropologists. I hope that this Presidential Address will

of Margaret Mead was used by permission from Barnard

contribute to that effort. Finding and revaluing these indiCollege Archives; the photo of Alfonso Ortiz was used by

viduals stems from an impulse to find role models from the

permission from Elena Ortiz; the photo of Elsie Clews Par-

past but also from the notion that semioutsiders-because

sons was used by permission from the American Philo-

of their positionality-bring new insights, new theories,

sophical Society (Collection II, Series VII); the photo of

and especially new sources of critique to the discipline as a

Michelle Zimbalist Rosaldo was used by permission from

whole. However, the incorporation of our historically

Dorothy Zimbalist; and the photo of Gladys Reichard was

marginal anthropologists is not yet complete. We need to

used by permission from the Museum of Northern Ari-

teach their work (and that of others like them) in our thezona.

ory classes and make their writing part of the anthropo-

logical canon as it is represented in textbooks and histoNOTES

ries of the discipline. Rather than attention to a few of the

Acknowledgments. This article is a revised and more formal version

more well-known women scholars (e.g., Mead and

of my presidential address delivered at the AAA Annual Meetings,

December 1, 2001, in Washington, D.C. I wish to acknowledge the

Benedict) or the use of one collection of essays, a much

Russell Sage Foundation that supported me as a visiting scholar

wider-ranging set of comparisons and analysis is necessary

during fall 2001 when I was writing the address. I would also like

if we are to present our students with the full history of

to thank Sabrina Neem, Peter Bret Lamphere, and Peter Evans who

provided typing and editorial support. At the University of New

anthropology.

Mexico, Megan Underwood and Gabriel Torres helped with revi-

Despite a generation of efforts we still have work to

sions. Finally, I would like to thank Susan Lees and Fran Mascia-

do. We must not fool ourselves: Although white women

Lees for helping me to clarify and sharpen the argument in this

have made great progress, we are a long way from fully in-

corporating minority men and women into anthropology.

version.

1. Nancy Parezo outlines the marginalization of women in anthro-

pology in her chapter "Anthropology: the Welcoming Science."

It will take several decades of hard work before this goal is

She reminds us that women have struggled to obtain higher de-

achieved. Minority students still have a difficult time findgrees in anthropology and tenured jobs in major institutions. Even

ing financial assistance for a graduate degree, and they are

Columbia, which later produced 20 women Ph.D.s between

1920-40, was a relatively inhospitable place for women in the early

often too isolated and underrepresented in departments to

1900s. Of 160 women enrolled in advanced social science and phi-

sustain a commitment to the discipline. We still bear the

losophy courses between 1899-1906, only two--Elsie Clews Par-

colonial heritage of our discipline, particularly among Nasons and Naomi Norsworthy-were awarded Ph.D.s. At Harvard, as

tive American populations, which makes it difficult to forge

late as the 1940s, Laura Thompson recalled that women "had to sit

in the hall while men attended classes" and Alfred Tozzer told his

collaborative relationships with communities we study.

Radcliffe students (including Eleanor Leacock) that women were

And in some departments there still is animosity towards

not welcome in anthropology (Parezo 1993:6, 18, 19).

applied anthropology and writing for the public, making

2. Other women anthropologists in this situation were Ruth Lan-

difficult the forging a new activism that combines re-

des, Ruth Bunzel, Frederica de Laguna, Dorothy Keur, and Kate

Peck Kent. Still others like Ruth Underhill, Laura Thompson, and

search, writing, and public advocacy within the academy.

Rosamund Spicer spent considerable portions of their careers as

As we begin the AAA's second century, we need to

government or applied anthropologists. Women archaeologists

nurture those on the margins and find ways in which they

like Bertha Dutton and Florence Hawley Ellis were employed in

can be fully incorporated into the ever-changing defini-

museums and in new departments in Western universities (Parezo

1993).

tion of what anthropology is. Mindful that we need to

3. The careers of the first generation of 17 African American an-

continue to recuperate a different view of our past, these

thropologists are outlined in Harrison and Harrison 1999. Other

unofficial histories offer a reading of anthropology's greatNative American scholars include William Jones (Mesquakie) who

est strengths.

received a Ph.D. from Columbia in 1906, Frances La Flesche

(Omaha) who was employed as an anthropologist by the BAE, and

Alfonso Ortiz (Tewa), Ed Dozier (Tewa), and Edmund Ladd (Zuni)

who received advanced degrees in the 1950s and 1960s. Many Na-

LOUISE LAMPHERE Department of Anthropology, University

tive American ethnographers (e.g., Ely Parker [Seneca] who worked

of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131

with Lewis Henry Morgan) have been recognized as American In-

dian Intellectuals (Liberty 1978) but have rarely been seen as true

collaborators. Attention is only now being given to the handful of

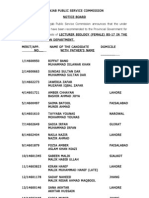

PHOTO PERMISSIONS

Hispano/Chicano/Mexican anthropologists such as Manuel Gamio

The photos used in this Presidential Address were pro-

vided by the following: The photo of Ella Deloria was used

who earned his Ph.D. under Boas in 1922 and who founded an-

thropology in Mexico.

This content downloaded from 196.11.235.231 on Fri, 04 Mar 2016 13:30:34 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

138 American Anthropologist * Vol. 106, No. 1 * March 2004

4. My own Title VII suit at Brown University, which was settled

Barnard, Alan

2000 History and Theory in Anthropology. Cambridge: Cam-

successfully in 1977 when I was awarded tenure and promotion,

indicates how difficult it was for women to become senior profes-

sors in Ivy League universities. I was denied tenure in May 1974

bridge University Press.

Basso, Keith

1997 Eulogy for Alfonso Ortiz:January 30, 1997. Unpublished MS.

and sued Brown University in the spring of 1975. Three other

Bateson, Mary Catherine

plaintiffs joined me in this suit, after it was certified as a class ac-

1984 With a Daughter's Eye: A Memoir of Margaret Mead and Gretion. When the suit was settled in September 1977, I and two other

gory Bateson. New York: William Morrow and Co.

women were awarded tenure and promotion. Brown University

Benedict, Ruth

was under a Consent Decree from 1977 until the early 1990s, and

1934 Patterns of Culture. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

the proportion of women faculty went from 10 percent in 1978 to