Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Warren Buffett and Wall Street

Caricato da

coolchadsCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Warren Buffett and Wall Street

Caricato da

coolchadsCopyright:

Formati disponibili

AND

WARREN WALL

BUFFETT STREET

The Best of Frenemies

16 FINANCIAL HISTORY | Fall 2015 |www.MoAF.org

Louie Psihoyos/CORBIS

Lawrence A. Cunningham

In 1965, when 35-year-old Nebraskan

Warren Buffett took control of Berkshire

Hathaway, Inc., a dying New England

textile company, the local press portrayed

him as a Wall Street takeover artist: a

liquidator of the sort that inspired Danny

DeVitos fiendish character in Other

Peoples Money. True, Buffett acquired

Berkshire on the cheapfor a fraction

of its $22 million book value of $19.24

per shareand eventually shuttered the

mills. But he has always campaigned vigorously against hostile bids, heavy borrowing, asset flipping and other controversial Wall Street practices.

Buffett became a vocal critic of Wall

Street, as he favored cash to debt, held

companies for the long term and defended

trustworthy managers against short-term

pressures. His oratory sounded more like

the high-minded defender of the corporate

bastion in Other Peoples Money, played

by Gregory Peck, than an apostle of greed.

Speaking as the reluctant interim chairman

of Salomon after its 1991 bond trading scandal, for instance, Buffett famously broadcast

to Congress a new credo given to his Wall

Street bankers: Lose money for the firm,

even a lot of money, and I will be understanding; lose reputation for the firm, even

a shred of reputation, and I will be ruthless.

In addition to steady criticism, however, Buffett has also been a vital friend to

Wall Street. His stint as Salomon chairman followed from Berkshires white

squire stake in the investment bank,

designed to deter a hostile takeover bid.

The year was 1987, when Salomons largest

shareholder grew frustrated with management and flirted with selling a 12% block

to Ron Perelman, the corporate raider

who had recently seized control of Revlon.

Fearful of being next, Salomon CEO John

Gutfreund turned to Buffett, who pledged

fidelity while buying a sizable issue of convertible preferred stock yielding 9%.

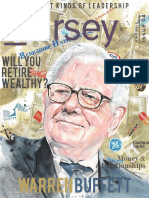

Berkshire Hathaway CEO Warren Buffett.

Buffetts cultivation of a reputation for

offering hands-off long-term capital dates

back to 1973 when Berkshire accumulated

a stake in The Washington Post Co. Buffett vowed loyalty to CEO Kay Graham,

who soon asked him to join the board. In

1986, Buffett went further when Berkshire

took a large position in Capital Cities/

ABC, giving its managers, Dan Burke

and Tom Murphy, proxy power to vote

Berkshires shares as they saw fit. During

that era of hostile takeovers, Berkshire and

Buffett likewise backed managers against

raiders at companies such as Champion

and Gillette, and defeated Ivan Boeskys

run at Scott Fetzer, paying $315 million

to acquire the conglomerate, which Berkshire still owns to this day.

Wall Street values Buffetts reputation

along with Berkshires balance sheet. In the

25 days after the 2008 collapse of Lehman

Brothers, Berkshire invested $15.6 billion

in numerous companies, when most of

corporate America was starved for credit.

For one, Berkshire staked $5 billion for

preferred stock in Goldman Sachs, paying

a 10% dividend and redeemable for a 10%

premium. Berkshire also got an option to

buy a similar amount of Goldman common stock at $115 per share, below the market price of $125, making it in the money.

In 2011, after the crisis passed, Goldman redeemed the preferred. So Berkshire

earned a few years of dividends plus the

buyback premium, adding to $1.8 billion.

In early 2013, Berkshire exercised its option

to buy Goldman common. Rather than pay

the $5 billion cash price (then worth $6.4

billion), Berkshire took stock valued at the

difference of $1.4 billion. Berkshires total

gain on its $5 billion investment was $3.2

billion, 64% in a few yearsalong with 3%

of Goldmans common stock it still owns.

Meanwhile, Bank of America continued to struggle to the point where, in

2011, it likewise turned to Berkshire for a

$5 billion investment. Berkshire received

preferred stock paying a 6% dividend

and redeemable for a 5% premium. In

addition, Berkshire obtained warrants to

purchase 700 million shares of the banks

common stock at a per share exercise

price of $7.14, or just under $5 billion.

Such a stake is worth more than twice that

today ($11.2 billion at the stocks recent

price of $16) and would represent a greater

than 6% interest in the bank. If Berkshire

exercises the warrants in 2021, on the eve

of expiration, it will add to an investment portfolio already boasting such big

stakes in venerable institutions of finance,

including American Express, Moodys

Investor Service and Wells Fargo.

Berkshire and Buffett have always been

bullish on corporate America, yet they

behave quite differently from most managers and their Wall Street advisers alike.

For instance, unlike most American corporations and their financiers, Berkshire

shuns debt as costly and constraining.

Since 1967, the preferred form of leverage

has arisen from internal insurance operations. Customers pay premiums up front

in exchange for claims to be paid later, if at

all, and insurers get to invest the proceeds,

called float, in the interim. Float offers

more attractive leverage than debt since

there are no coupons, due dates, covenantsor Wall Street bankers and fees.

Berkshire now owns marquee companies

in the insurance field, including National

Indemnity, GEICO and Gen Re, and commands float exceeding $85 billion.

In typical takeovers, whether by strategic buyers across corporate America or

financial buyers from Wall Street, acquirers always intervene, invariably change

strategy and frequently replace management. Berkshires opposite tack makes it

an attractive alternative for sellers of businesses seeking autonomy. They also relish

Berkshires sense of permanence, particularly compared to Berkshires rivals from

Wall Streets private equity funds. In private equitys leveraged buyouts, businesses

face not only leverage and intervention, but

the funds charge high fees and make quick

exits, meaning rapid change followed by a

sale. Berkshire, in contrast, imposes no fees

and has not sold a subsidiary in 40 years.

While Wall Street sponsored hostile

bidders and junk-bond buyouts to break

up vast conglomerates, Buffett was not

only defending corporate managers but

www.MoAF.org | Fall 2015 | FINANCIAL HISTORY17

Courtesy of Scripophily.com The Gift of History.

Rare specimen Class B stock certificate from Berkshire Hathaway Inc., printed in 1996.

building Berkshire into one of the largest conglomerates in history. Today, in

addition to an investment portfolio of two

dozen stocks worth more than $100 billion, Berkshire is comprised of 65 different

wholly-owned subsidiaries, nine of which

would be Fortune 500 companies standing

alone. The conglomerate is worth more

than $500 billion with a per share book

value exceeding $100,000marking a

20% compound annual growth rate from

Buffetts assumption of control.

Berkshires Clayton Homes subsidiary

is the nations largest builder and financier

of manufactured housing, most sold to

lower income Americans. On Wall Street,

Clayton repackages substantial portions

of its loans into mortgage-backed securities. In 2008, investors in other securitized

mortgage loans faced steep defaults, due

to lax lending practices of originators

along with poor quality control during the

securitization process. But Claytons securitized loans fully performed, repaying all

principal and interest. It is not because of

customer credit quality, which is weak,

but because despite low credit scores,

Clayton only lends to borrowers on terms

they likely can repaybased on an examination of assets and income and without

escalating teaser interest rates.

Berkshires unique practices do not

always succeed. Take its aversion to middlemen in the acquisitions arena. Berkshire does not scout for deals but rather

waits for the phone to ring, as Buffett puts it. Buffett evaluates opportunities alone or with advice only from Vice

Chairman Charlie Munger, foregoing the

professionals that most companies hire to

conduct due diligence. While the practice

has generally yielded strong results, costly

mistakes have occurred, ranging from the

total loss of $443 million paid in 1993 using

Berkshire stock for a disintegrating shoe

maker to a $1 billion after-tax loss on debt

Berkshire staked in 2007 on a failed leveraged buyout of Texas utility companies.

18 FINANCIAL HISTORY | Fall 2015 |www.MoAF.org

Berkshires $22 billion 1999 acquisition

of Gen Re, also paid in Berkshire stock,

dramatized the pitfalls: unbeknownst to

Buffett when Berkshire bought Gen Re, its

underwriting standards had deteriorated,

its derivatives book had become bloated

and its exposure to catastrophic risks was

unduly concentrated. Without Berkshire,

Gen Res losses covering the 9/11 terrorist

attacks on New Yorks Financial District

would likely have rendered it insolvent.

Consider Buffetts trust-based philosophy of granting managers unbridled autonomy. While lauded within the company

and responsible for much of Berkshires

success at the subsidiary level, costly management shifts sometimes result. Costs are

revealed in several well-publicized CEO

departures, including multiple successive

resignations within several years at each

of Benjamin Moore, Gen Re and NetJets.

The most dramatic departure occurred

in 2011 when David Sokol, widely seen as

a likely successor to Buffett, was caught

Courtesy of Scripophily.com The Gift of History.

Berkshire Hathaway Inc. stock certificate, dated March 17, 2010.

front-running: a form of insider trading

in which he bought shares in a publicly

traded stock, Lubrizol, ahead of pitching

the company as a Berkshire acquisition

candidate. While the scandal prompted

questions about Berkshires lack of formal vetting and grooming of top executives, Buffetts response also raised eyebrows. After Buffett learned of Sokols

front running, he drafted a press release

himself. The release, which spoke of

Sokols extraordinary contributions to

Berkshire and expressed Buffetts opinion

that Sokol had done nothing illegal, drew

sharp criticism, given Buffetts traditional

high standard of rectitude.

The approach reflected Buffetts antipathy

to corporate bureaucracy, which similarly

translates into substantial net savings, but

with costs. For instance, Berkshire has no

centralized departments such as communications, human resources or legal. Yet such

frugality can leave subsidiaries flatfooted

in response to the inevitable investigative

journalism targeting them. One such expos

attacked Berkshires practice of generating substantial funds from float, suggesting

it gives personnel at National Indemnity

perverse incentives to avoid or delay paying

legitimate claimseven in bad faith.

Another piece challenged Clayton

Homes, arguing that its employees pressure customers into unaffordable financing arrangements and follow up with

aggressive collection practices. After publication, both subsidiaries and Berkshire

corrected errors in the stories, but the

damage had been done. A full-time professional who makes engagement with

journalists a top priority would likely have

altered the shape of the original reports, a

better outcome than the thrust and parry

that now defines the public record. Berkshire acts as if it is small, but it is a Goliath

to reporters and readers alike.

Buffett is critical of Wall Street and

other financial intermediaries primarily for unnecessary complexity and

corresponding costs. His core message

for Wall Street remains valuable: simplicity. Parsimony and frugality underpin the

Berkshire model which, while imperfect,

has delivered substantial net gains, thanks

to these hallmarks: investment in reputation; commitment to trust, loyalty and

autonomy; avoiding hostile or leveraged

acquisitions; self-reliance in corporate

administration; and permanent ownership of subsidiaries.

Fifty years after Buffett took control of

Berkshire, the 85-year-old Omaha denizen

still has much to offer Wall Street, in capital and wisdom alike. He is certainly more

Peck than DeVito.

Lawrence A. Cunningham, a professor

at George Washington University, is the

co-author and publisher of The Essays

of Warren Buffett: Lessons for Corporate America and author of Berkshire

Beyond Buffett: The Enduring Value of

Values.

www.MoAF.org | Fall 2015 | FINANCIAL HISTORY19

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Seth Klarman On The Painful Decision To Hold CashDocumento2 pagineSeth Klarman On The Painful Decision To Hold CashIgor Chalhub100% (5)

- Characteristics: Equity Cash Flow Cost of CapitalDocumento5 pagineCharacteristics: Equity Cash Flow Cost of CapitalfunmastiNessuna valutazione finora

- Investments - Charles Munger - Damn RightDocumento524 pagineInvestments - Charles Munger - Damn Rightalroy dcruz100% (1)

- StockGuide Q4 2022Documento32 pagineStockGuide Q4 2022Falls Outsss100% (1)

- Charlie Munger ValueWalk PDF FinalDocumento43 pagineCharlie Munger ValueWalk PDF FinalRajivShahNessuna valutazione finora

- Mohnish Pabrai One of The Things That I Learned From Warren Buffett Is A Team in An Investment OperaDocumento27 pagineMohnish Pabrai One of The Things That I Learned From Warren Buffett Is A Team in An Investment Operasuresh420Nessuna valutazione finora

- BerkshireHandout2012Final 0 PDFDocumento4 pagineBerkshireHandout2012Final 0 PDFHermes TristemegistusNessuna valutazione finora

- Spinoff Investing Checklist: - Greggory Miller, Author of Spinoff Investing Simplified Available OnDocumento2 pagineSpinoff Investing Checklist: - Greggory Miller, Author of Spinoff Investing Simplified Available OnmikiNessuna valutazione finora

- Quality of Earnings Thornton L o PDF 1413879Documento2 pagineQuality of Earnings Thornton L o PDF 1413879Ashutosh GuptaNessuna valutazione finora

- Book Review - One Upon Wall StreetDocumento20 pagineBook Review - One Upon Wall StreetPriya UpadhyayNessuna valutazione finora

- Investments Reading ListDocumento2 pagineInvestments Reading Listofb1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Warren Buffett Early YearsDocumento40 pagineWarren Buffett Early YearsRishab Wahal100% (1)

- Warren Buffett - An InvestographyDocumento178 pagineWarren Buffett - An InvestographyRajesh AgarwalNessuna valutazione finora

- Berkshare Hathway Case StudyDocumento17 pagineBerkshare Hathway Case StudyYogesh Sangle100% (2)

- Warren Buffett Predicts The Future (Preview Edition, 1.1)Documento104 pagineWarren Buffett Predicts The Future (Preview Edition, 1.1)Carolina TorresNessuna valutazione finora

- Value InvestingDocumento7 pagineValue InvestingAbdullah18Nessuna valutazione finora

- Geico Case Study PDFDocumento22 pagineGeico Case Study PDFMichael Cano LombardoNessuna valutazione finora

- Negotiating and Complying With Credit Agreements PDFDocumento17 pagineNegotiating and Complying With Credit Agreements PDFDaveNessuna valutazione finora

- Warren BuffetDocumento24 pagineWarren BuffetDalpat Singh Purohit100% (2)

- 35 Years of Buffett's Greatest Investing Wisdom: Enter Keywords or TickerDocumento4 pagine35 Years of Buffett's Greatest Investing Wisdom: Enter Keywords or TickerGurjeevAnandNessuna valutazione finora

- Beautiful Investment AnalysisDocumento10 pagineBeautiful Investment AnalysisJohnetoreNessuna valutazione finora

- Future Authoring Future of CodingDocumento20 pagineFuture Authoring Future of CodingcoolchadsNessuna valutazione finora

- The Playing Field - Graham Duncan - MediumDocumento11 pagineThe Playing Field - Graham Duncan - MediumPradeep RaghunathanNessuna valutazione finora

- GMO 2009 1st Quarter Investor LetterDocumento14 pagineGMO 2009 1st Quarter Investor LetterBrian McMorris100% (2)

- Exercises-Stock ValuationDocumento2 pagineExercises-Stock ValuationErjohn Papa50% (2)

- Buffett in Hindsight Foresight (2002)Documento8 pagineBuffett in Hindsight Foresight (2002)MWGENERALNessuna valutazione finora

- FinancialIntelligence MediaKitDocumento6 pagineFinancialIntelligence MediaKitElvis Oloton0% (1)

- Duracell's Acquisition by Berkshire Hathaway - A Case Study FinalDocumento12 pagineDuracell's Acquisition by Berkshire Hathaway - A Case Study Finaltanya batraNessuna valutazione finora

- Lazar Blue Book Chapter 4 Solution (1 To 14 Only)Documento27 pagineLazar Blue Book Chapter 4 Solution (1 To 14 Only)Shuhada Shamsuddin75% (4)

- Citi January 2017Documento102 pagineCiti January 2017CrowdfundInsider100% (2)

- Charlie Munger's ArticleDocumento20 pagineCharlie Munger's Articlesrinivasan9Nessuna valutazione finora

- Investment ChecklistDocumento4 pagineInvestment ChecklistlowbankNessuna valutazione finora

- Notes On "A Morning With Charlie" Forum With Charlie Munger, Held in Pasadena, CA On 7/1/11. Prepared by Pat DorseyDocumento8 pagineNotes On "A Morning With Charlie" Forum With Charlie Munger, Held in Pasadena, CA On 7/1/11. Prepared by Pat Dorseylibrivox01Nessuna valutazione finora

- File PDFDocumento4 pagineFile PDFGurjeevNessuna valutazione finora

- Edition 1Documento2 pagineEdition 1Angelia ThomasNessuna valutazione finora

- World Wealth Report 2020Documento40 pagineWorld Wealth Report 2020Rafael CarrasquelNessuna valutazione finora

- TL 9000 Requirements Handbook Release 5.5 ChangesDocumento33 pagineTL 9000 Requirements Handbook Release 5.5 Changescoolchads0% (1)

- How To Identify Wide MoatsDocumento18 pagineHow To Identify Wide MoatsInnerScorecardNessuna valutazione finora

- CPAR TOA Pre-Board FinalDocumento10 pagineCPAR TOA Pre-Board FinalJericho Pedragosa100% (1)

- 1976 Buffett Letter About Geico - FutureBlindDocumento4 pagine1976 Buffett Letter About Geico - FutureBlindPradeep RaghunathanNessuna valutazione finora

- Profiles in Investing - Marty Whitman (Bottom Line 2004)Documento1 paginaProfiles in Investing - Marty Whitman (Bottom Line 2004)tatsrus1Nessuna valutazione finora

- A Project Report On NSEDocumento48 pagineA Project Report On NSEraghavhindi75% (8)

- 2007.10.29 Paulson Credit Crisis PresentationDocumento34 pagine2007.10.29 Paulson Credit Crisis Presentationadjk97Nessuna valutazione finora

- Warren E Buffett 2008 CaseDocumento9 pagineWarren E Buffett 2008 CaseAnuj Kumar GuptaNessuna valutazione finora

- Screening For Stocks Using The Dividend Adjusted Peg RatioDocumento6 pagineScreening For Stocks Using The Dividend Adjusted Peg RatioHari PrasadNessuna valutazione finora

- Who Are India's Best Equity Investors Who Invest For Themselves - QuoraDocumento3 pagineWho Are India's Best Equity Investors Who Invest For Themselves - QuoraHemjeet BhatiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Leveraged BuyoutDocumento8 pagineLeveraged Buyoutmanoraman0% (1)

- (Note The Footnotes) : Jim Donald Food RetailingDocumento5 pagine(Note The Footnotes) : Jim Donald Food RetailingDealBook100% (1)

- Mark Sellers Speech To Investors - Focus On The Downside, and Let The Upside Take Care of ItselfDocumento5 pagineMark Sellers Speech To Investors - Focus On The Downside, and Let The Upside Take Care of Itselfalviss127Nessuna valutazione finora

- Bruce Berkowitz On WFC 90sDocumento4 pagineBruce Berkowitz On WFC 90sVu Latticework PoetNessuna valutazione finora

- Bridgewater Seeks Competitive Advantage Through Lateral ThinkingDocumento2 pagineBridgewater Seeks Competitive Advantage Through Lateral ThinkingOasux100% (1)

- Michael L Riordan, The Founder and CEO of Gilead Sciences, and Warren E Buffett, Berkshire Hathaway Chairman: CorrespondenceDocumento5 pagineMichael L Riordan, The Founder and CEO of Gilead Sciences, and Warren E Buffett, Berkshire Hathaway Chairman: CorrespondenceOpenSquareCommons100% (27)

- Private Equity Insider 051210Documento8 paginePrivate Equity Insider 051210tonyspringNessuna valutazione finora

- Distressed Debt InvestingDocumento5 pagineDistressed Debt Investingjt322Nessuna valutazione finora

- Summary New Venture ManagementDocumento57 pagineSummary New Venture Managementbetter.bambooNessuna valutazione finora

- CGRP38 - Corporate Governance According To Charles T. MungerDocumento6 pagineCGRP38 - Corporate Governance According To Charles T. MungerStanford GSB Corporate Governance Research InitiativeNessuna valutazione finora

- Graham & Doddsville Spring 2011 NewsletterDocumento27 pagineGraham & Doddsville Spring 2011 NewsletterOld School ValueNessuna valutazione finora

- Here Are A Few Relevant ExamplesDocumento6 pagineHere Are A Few Relevant ExamplesTeddy RusliNessuna valutazione finora

- My Investment StrategyDocumento31 pagineMy Investment StrategyErnst GrönblomNessuna valutazione finora

- VIIWordsofWisdom PDFDocumento43 pagineVIIWordsofWisdom PDFRajeev BahugunaNessuna valutazione finora

- Warren Buffett: "The Investor of Today Does Not Profit From Yesterday'S Growth"Documento19 pagineWarren Buffett: "The Investor of Today Does Not Profit From Yesterday'S Growth"Anshul AggarwalNessuna valutazione finora

- Wealth Creation Study MoslDocumento48 pagineWealth Creation Study MosldidwaniasNessuna valutazione finora

- Charlie Munger - The Complete Investor by Tren Griffin - Edelweiss MFDocumento4 pagineCharlie Munger - The Complete Investor by Tren Griffin - Edelweiss MFBanderlei SilvaNessuna valutazione finora

- Circle of CompetenceDocumento4 pagineCircle of CompetenceKrešimir DodigNessuna valutazione finora

- 003 Investment PhilospohiesDocumento12 pagine003 Investment PhilospohiesedziissNessuna valutazione finora

- Leveraged BuyoutDocumento9 pagineLeveraged Buyoutbharat100% (1)

- Berkshire HathwayDocumento9 pagineBerkshire HathwaypraneethadepuNessuna valutazione finora

- Bajaj Elec Conf Cal PDFDocumento16 pagineBajaj Elec Conf Cal PDFcoolchadsNessuna valutazione finora

- Q4FY16 WCL TranscriptDocumento13 pagineQ4FY16 WCL TranscriptcoolchadsNessuna valutazione finora

- Zydus WellnessDocumento14 pagineZydus WellnesscoolchadsNessuna valutazione finora

- WWW Sleepycapital Com An Evening With Mohnish Pabrai PabraiDocumento19 pagineWWW Sleepycapital Com An Evening With Mohnish Pabrai PabraicoolchadsNessuna valutazione finora

- WWW Newyorker Com Magazine 2015-04-27 Where Are The ChildrenDocumento50 pagineWWW Newyorker Com Magazine 2015-04-27 Where Are The ChildrencoolchadsNessuna valutazione finora

- Seinfeld Technique PDFDocumento1 paginaSeinfeld Technique PDFcoolchadsNessuna valutazione finora

- Forbes India Dec 2014-1 PDFDocumento62 pagineForbes India Dec 2014-1 PDFcoolchadsNessuna valutazione finora

- Vakrangee AnnualResult PressRelease 22 May 14Documento2 pagineVakrangee AnnualResult PressRelease 22 May 14coolchadsNessuna valutazione finora

- 4QFY10 Allied Digital TranscriptDocumento18 pagine4QFY10 Allied Digital TranscriptcoolchadsNessuna valutazione finora

- Page 53Documento1 paginaPage 53coolchadsNessuna valutazione finora

- Handout No. 4+Documento6 pagineHandout No. 4+Zyrelle DelgadoNessuna valutazione finora

- Financial Management TheoryDocumento7 pagineFinancial Management TheoryAnandhi SomasundaramNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 13Documento11 pagineChapter 13Maya HamdyNessuna valutazione finora

- WK - 5 - Cost of Capital Capital Structure PDFDocumento40 pagineWK - 5 - Cost of Capital Capital Structure PDFreginazhaNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 16 Day 1 EPS - ComplexDocumento5 pagineChapter 16 Day 1 EPS - Complexgilli1trNessuna valutazione finora

- Tarea 9 Finanzas CorpDocumento7 pagineTarea 9 Finanzas Corpvuzo123Nessuna valutazione finora

- Solution - Shareholders' EquityDocumento14 pagineSolution - Shareholders' EquityjhobsNessuna valutazione finora

- Keown Valuation and Charactheristic of StockDocumento44 pagineKeown Valuation and Charactheristic of Stockmaya husniaNessuna valutazione finora

- Nism Series II B Registrar To An Issue Mutual Funds Workbook in PDFDocumento184 pagineNism Series II B Registrar To An Issue Mutual Funds Workbook in PDFLingamplly Shravan KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Master Circular On Foreign Investment in IndiaDocumento91 pagineMaster Circular On Foreign Investment in IndiaVidya1986Nessuna valutazione finora

- Accounting IAS Model Answers Series 3 2006 Old SyllabusDocumento20 pagineAccounting IAS Model Answers Series 3 2006 Old SyllabusAung Zaw HtweNessuna valutazione finora

- N Ew Venture Finance S Ession 3: C Ap Tables, Valuation & Deal TermsDocumento55 pagineN Ew Venture Finance S Ession 3: C Ap Tables, Valuation & Deal Termsutkarshrawal89Nessuna valutazione finora

- Corporate Reporting (International) : September/December 2017 - Sample QuestionsDocumento9 pagineCorporate Reporting (International) : September/December 2017 - Sample QuestionsVinny Lu VLNessuna valutazione finora

- Advanced Financial Accounting 12th Edition Christensen Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocumento67 pagineAdvanced Financial Accounting 12th Edition Christensen Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFSandraMurraykean100% (12)

- Wild Shaw (8th Ed.) Connect GuideDocumento494 pagineWild Shaw (8th Ed.) Connect GuideSrikar RootsNessuna valutazione finora

- Financial Accounting Sem 2 (2019-2020) Lecturer: Mr. Vu Tuan Anh, CMA, MSA Email: (Preferred) Tutor: Ms. Tran My HaDocumento73 pagineFinancial Accounting Sem 2 (2019-2020) Lecturer: Mr. Vu Tuan Anh, CMA, MSA Email: (Preferred) Tutor: Ms. Tran My HaTrâm PhạmNessuna valutazione finora

- Airborne Freight Corporation Reports Third Quarter 1997 ResultsDocumento2 pagineAirborne Freight Corporation Reports Third Quarter 1997 Resultscychen_scribdNessuna valutazione finora

- Seatwork 02 InvestmentsDocumento2 pagineSeatwork 02 InvestmentsJella Mae YcalinaNessuna valutazione finora

- MAS-42E (Budgeting With Probability Analysis)Documento10 pagineMAS-42E (Budgeting With Probability Analysis)Fella GultianoNessuna valutazione finora

- Hindes Jacobs Appeals Brief 17 3794 0016Documento92 pagineHindes Jacobs Appeals Brief 17 3794 0016Schrodinger StateofwarNessuna valutazione finora

- PRELIM-EXAMS 2223 with-ANSWERDocumento5 paginePRELIM-EXAMS 2223 with-ANSWERbrmo.amatorio.uiNessuna valutazione finora

- Share and Share CapitalDocumento6 pagineShare and Share CapitalDanish KhattarNessuna valutazione finora

- Session 7 - Equity - For Students and MoodleDocumento74 pagineSession 7 - Equity - For Students and Moodless9723Nessuna valutazione finora

- INVESTMENTSDocumento9 pagineINVESTMENTSKrisan RiveraNessuna valutazione finora

- AsdsdasdasDocumento3 pagineAsdsdasdasKenneth Bryan Tegerero TegioNessuna valutazione finora

- Corporate Finance Cost of Capital: Dr. Avinash Ghalke, CFADocumento20 pagineCorporate Finance Cost of Capital: Dr. Avinash Ghalke, CFAmansi agrawalNessuna valutazione finora