Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

gt0513 Ayyala PDF

Caricato da

rafikaDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

gt0513 Ayyala PDF

Caricato da

rafikaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

cover story

ONLINE SURVEY

Fuchs Heterochromic

Iridocyclitis and

Posner-Schlossman

Syndrome

Early detection and diagnosis are essential to properly managing these diseases.

By Mathew George, MD, and Ramesh Ayyala, MD, FRCS(E), FRCO phth

uchs heterochromic iridocyclitis (FHI) and PosnerSchlossman syndrome (PSS) are closely related

inflammatory causes of glaucoma. This article

describes specific etiopathologies and general

strategies for managing these conditions.

FUCHS HETEROCHROMIC IRIDOCYCLITIS

Presentation

Initially described in 1906 by Austrian ophthalmologist Ernst Fuchs, FHI generally presents as a mild unilateral inflammation of the anterior chamber with stellate

keratic precipitates and iris heterochromia with prominent iris and angle vessels secondary to iris atrophy that

represents about 2% to 7% of cases of anterior uveitis.1

In rare cases, FHI may present bilaterally with occasional

evidence of snowbanking at the pars plana. Patients

usually have symptomatic vision loss secondary to cataract formation and tend not to have significant inflammation on examination. Elevated IOP is not a consistent

phenomenon but can occur secondary to peripheral

anterior synechiae, trabecular scarring, rubeosis, lensinduced angle closure, recurrent spontaneous hyphema,

and steroid-induced ocular hypertension.

Etiology

Historical etiological theories for FHI included sympathetic denervation, which could account for iris

hypochromia, and infectious etiologies such as herpes

simplex virus, toxoplasma, and cytomegalovirus (CMV).

Evidence increasingly suggests, however, an association

between the rubella virus and FHI. In a study looking

at aqueous humor antibody index and the presence

of viral genome by polymerase chain reaction (PCR),

rubella antibodies were detected in almost all eyes with

FHI, and the rubella genome was found in almost half

of the patients who were younger than 40 years old.2

Cellular component analysis in FHI reveals a predominance of T-lymphocyte markers CD3 and CD4, suggestive of viral etiopathogenesis.3 CMV was also identified

by PCR testing in a large number of eyes with clinical

evidence of FHI.4 Thus, a viral etiology would explain

FHIs general unresponsiveness to topical steroid therapy, which in many cases is unnecessary and can have

untoward side effects.

Evidence has also suggested that the incidence of FHI

has decreased since the introduction of the measles,

mumps, and rubella vaccinations.5 Ocular manifestations

of congenital rubella syndrome include congenital cataracts, glaucoma, microphthalmia, and pigmentary retinal

changes, and this occurs in infants born to mothers

infected in the first trimester. Rubella antibodies are seen

in children infected after the first trimester, indirectly

suggesting a late-trimester infection that may manifest

as FHI.6

May/June 2013glaucoma today49

cover story

FHI and Glaucoma

Glaucoma occurs in 10% of patients with FHI at presentation, with an incidence risk of 0.5% per year.7 It

is important that ophthalmologists watch for a rise in

IOP and the formation of peripheral anterior synechiae

with chronic damage to the trabecular meshwork,

especially after cataract surgery, which can lead to

intraoperative bleeding from angle vessels.

Management

Medical management is a reasonable but generally

futile option, with failure reported in more than 70% of

patients. Although trabeculectomy with antimetabolites

is successful in 60% to 70% of patients 2 years postoperatively,8 glaucoma drainage implants have over a 90%

success rate 1 year postoperatively and a 50% success

rate after 4 years postoperatively.9 Our preference is

to implant a pediatric Ahmed Glaucoma Valve (New

World Medical, Inc.) with an intracameral injection of

dexamethasone (Decadron; Merck & Co., Inc.). Cataract

surgery generally results in good visual outcomes, but it

may be associated with hyphema, uveitis, a small pupil,

and zonular dehiscence.

POSNER-SCHLOSSMAN SYNDROME

Presentation

Initially described by Posner and Schlossman in 1948,

PSS or glaucomatocyclitic crisis present with recurrent

unilateral attacks of significantly elevated IOP and minimal conjunctival injection, epithelial corneal edema, and

anterior chamber reaction in the form of small keratic

precipitates. Iris atrophy and heterochromia are frequently seen, whereas posterior synechiae typically are not.

Patients have open angles with normal IOP in between

attacks, which usually last a few hours to a few weeks.

Etiology

The various etiological theories proposed include

autonomic, vascular endothelial, and autoimmune dysfunction, but the infectious theory implicating CMV

seems to have the most evidence.10 Other organisms

implicated in PSS include Helicobacter pylori, varicellazoster virus, and herpes simplex virus.

Chee et al found in a cohort study that one-quarter

of patients with anterior uveitis tested positive for

CMV by aqueous humor PCR testing and that a large

majority of these patients had clinical evidence of PSS.11

The likelihood of being positive by PCR testing was

greater during an active episode of PSS. Oral antiviral

therapy reduced the frequency of attacks and other

sequelae in these patients. Although the seroprevalence

of CMV is high worldwide,12 the low frequency of PSS

50glaucoma todayMay/June 2013

Weigh in on

this topic now!

Direct link: https://www.research.net/s/GT12

1. How frequently do you encounter Fuchs heterochromic

iridocyclitis or Posner-Schlossman syndrome?

Often

Sometimes

Rarely

Never

2. With which treatment modality have you had the most

success in cases of Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis?

Medical therapy

Trabeculectomy with antimetabolites

Glaucoma drainage implants

Cataract surgery

3. With which treatment modality have you had the

most success in cases of Posner-Schlossman syndrome?

Topical IOP-lowering medications

Steroids

Cyclopegic agents

Filtering surgery

(1.9/100,000)13 may suggest that other genetic (eg, HLABw54)14 or coinfectious factors (eg, Helicobacter pylori)

may be necessary for clinical manifestation.

PSS and Glaucoma

In a study by Jap et al, about 25% of patients with

PSS had evidence of glaucoma, and those with 10 or

more years of clinical activity had a 2.8 times higher risk

of developing glaucoma.15 In a small series of patients,

changes to the optic nerve head were shown to be transient in the majority of cases.16

Management

The treatment of PSS includes topical IOP-lowering

medications, steroids, and cycloplegic agents. Filtering

surgery is successful in preventing IOP spikes and for

long-term IOP control.17 We start with medical therapy,

which includes prednisolone 1% and topical drops to

lower IOP and reserve incisional surgery for refractory

cases.

LINKS BETWEEN THE TWO DISEASES

Both FHI and PSS have common etiopathogenic and

clinical factors. A study that compared patients with FHI

and PSS found that over 50% of PSS patients and about

(Continued on page 53)

cover story

(Continued from page 50)

40% of FHI patients were positive for CMV.4 Patients

with presumed FHI who tested positive for CMV were

generally older men with nodular endothelial lesions.

There were no clinical differences between CMV positive

and negative patients with presumed PSS.

CONCLUSION

Both FHI and PSS are challenging problems. Careful

clinical examination followed by appropriate ancillary

testing and treatment is an effective strategy by which to

manage FHI and PSS. Clinicians should carefully consider

and administer antiviral therapy in eyes with recalcitrant

uveitis. Early detection and diagnosis with appropriate

observation are a must in combating these diseases. n

This research was supported in part by the Tulane

Glaucoma Research Fund.

Mathew George, MD, is a glaucoma fellow at

Tulane University Medical Center in New Orleans.

He acknowledged no financial interest in the products or companies mentioned herein. Dr. George

may be reached at mgeorge2@tulane.edu.

Ramesh Ayyala, MD, FRCS(E), FRCOphth, is

a professor of ophthalmology, director of the

Glaucoma Service, and director of residency

program at Tulane University Medical Center

in New Orleans. He has served as a consultant

to iScience Interventional and has received

research support from New World Medical, Inc. Dr. Ayyala

may be reached at rayyala@tulane.edu.

1. Wakefield D, Chang JH. Epidemiology of uveitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2005; 45(2):1-13.

2. Quentin CD, Reiber H. Fuchs heterochromic cyclitis: rubella virus antibodies and genome in aqueous humor.

Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138(1):46-54.

3. Gordon L. Fuchs heterochromic cyclitis: new clues regarding pathogenesis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138(1):133-134.

4. Chee SP, Jap A. Presumed Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis and Posner-Schlossman syndrome: comparison of

cytomegalovirus-positive and negative eyes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146(6):883-889.

5. Birnbaum AD, Tessler HH, Schultz KL, et al. Epidemiologic relationship between Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis

and the United States rubella vaccination program. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144(3):424-428.

6. Jones NP. Glaucoma in Fuchs heterochromic uveitis: aetiology, management and outcome. Eye (Lond).

1991;5(6):662-667.

7. Rothova A. The riddle of fuchs heterochromic uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144(3):447-448.

8. La Hey E, de Vries J, Langerhorst CT, et al. Treatment and prognosis of secondary glaucoma in Fuchs heterochromic

iridocyclitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993;116(3):327-340.

9. Da Mata A, Burk SE, Netland PA, et al. Management of uveitic glaucoma with Ahmed Glaucoma Valve implantation.

Ophthalmology. 1999;106(11):2168-2172.

10. Takusagawa HL, Liu Y, Wiggs JL. Infectious theories of Posner-Schlossman syndrome. Int Ophthalmol Clin.

2011;51(4):105-115.

11. Chee SP, Bacsal K, Jap A, et al. Clinical features of cytomegalovirus anterior uveitis in immunocompetent patients.

Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145(5):834-840.

12. Cannon MJ, Schmid DS, Hyde TB. Review of cytomegalovirus seroprevalence and demographic characteristics

associated with infection. Rev Med Virol. 2010;20(4):202-213.

13. Paivonsalo-Hietanen T, Tuominen J, Vaahtoranta-Lehtonen H, Saari KM. Incidence and prevalence of different

uveitis entities in Finland. Acta Ophthalmol Scand.1997;75(1):76-81.

14. Hirose S, Ohno S, Matsuda H. HLA-Bw54 and glaucomatocyclitic crisis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1985;103(12):18371839.

15. Jap A, Sivakumar M, Chee SP. Is Posner-Schlossman syndrome benign? Ophthalmology. 2001;108(5):913-918.

16. Dinakaran S, Kayarkar V. Trabeculectomy in the management of Posner-Schlossman syndrome. Ophthalmic Surg

Lasers. 2002;33(4):321-322.

17. Darchuk V, Sampaolesi J, Mato L, et al. Optic nerve head behavior in Posner-Schlossman syndrome. Int Ophthalmol.

2001;23(4-6):373-379.

May/June 2013glaucoma today53

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Alternative Health & Herbs Remedies 425 Jackson SE, Albany, OR 97321 1-541-791-8400Documento159 pagineAlternative Health & Herbs Remedies 425 Jackson SE, Albany, OR 97321 1-541-791-8400Marvin T Verna100% (2)

- Bahasa Inggris: Kumpulan N Al Latihan Njian Renerimaan Eal N Regawai Negeri NipilDocumento6 pagineBahasa Inggris: Kumpulan N Al Latihan Njian Renerimaan Eal N Regawai Negeri NipilrafikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Iaet 11 I 4 P 229Documento4 pagineIaet 11 I 4 P 229rafikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Busra AhmadDocumento1 paginaBusra AhmadrafikaNessuna valutazione finora

- AbstractDocumento8 pagineAbstractrafikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sanp 00174Documento5 pagineSanp 00174rafikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Acute Laryngitis and Croup: Diagnosis and TreatmentDocumento5 pagineAcute Laryngitis and Croup: Diagnosis and TreatmentIOSR Journal of PharmacyNessuna valutazione finora

- PharyngitisDocumento5 paginePharyngitisrafikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sanp 00174Documento5 pagineSanp 00174rafikaNessuna valutazione finora

- 21Documento3 pagine21rafikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Axelrod - Fam DysDocumento12 pagineAxelrod - Fam DysrafikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Bulletin UASVM, Veterinary Medicine 68 (2) /2011 pISSN 1843-5270 eISSN 1843-5378Documento5 pagineBulletin UASVM, Veterinary Medicine 68 (2) /2011 pISSN 1843-5270 eISSN 1843-5378Maybs Palec Pamplona-ParreñoNessuna valutazione finora

- Glaucoma ArticleDocumento4 pagineGlaucoma ArticlePrincess QumanNessuna valutazione finora

- PssDocumento2 paginePssrafikaNessuna valutazione finora

- In Focus SMADocumento8 pagineIn Focus SMAFlorentina NastaseNessuna valutazione finora

- Glaucoma ArticleDocumento4 pagineGlaucoma ArticlePrincess QumanNessuna valutazione finora

- N Diverticulitis PDFDocumento8 pagineN Diverticulitis PDFrafikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Wong Percy 15-3Documento15 pagineWong Percy 15-3rafikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Current Trends in Dravet Syndrome Research 2155 9562.1000152Documento5 pagineCurrent Trends in Dravet Syndrome Research 2155 9562.1000152rafikaNessuna valutazione finora

- 05 IntracranialDocumento4 pagine05 IntracranialrafikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Jurnal Glaukoma PrintDocumento15 pagineJurnal Glaukoma PrintrafikaNessuna valutazione finora

- TibDocumento7 pagineTibrafikaNessuna valutazione finora

- N Diverticulitis PDFDocumento8 pagineN Diverticulitis PDFrafikaNessuna valutazione finora

- 1416 PDFDocumento5 pagine1416 PDFrafikaNessuna valutazione finora

- ArticleDocumento10 pagineArticlerafikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Cover Paper THTDocumento1 paginaCover Paper THTrafikaNessuna valutazione finora

- SmaDocumento2 pagineSmarafikaNessuna valutazione finora

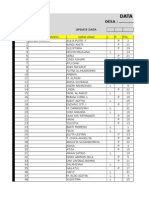

- Data Base Kia Muara BulianDocumento1.263 pagineData Base Kia Muara BulianrafikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Data Base Kia Muara BulianDocumento1.269 pagineData Base Kia Muara BulianrafikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Data Base Kia Muara BulianDocumento1.269 pagineData Base Kia Muara BulianrafikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Neuro Trauma: Nathan Mcsorley Speciality Trainee Neurosurgery 23B Ninewells HospitalDocumento35 pagineNeuro Trauma: Nathan Mcsorley Speciality Trainee Neurosurgery 23B Ninewells HospitalnathanNessuna valutazione finora

- Presented by DR Muhammad Usman Senior Lecturer BUCPT: Introduction To Screening For Referral in Physical TherapyDocumento27 paginePresented by DR Muhammad Usman Senior Lecturer BUCPT: Introduction To Screening For Referral in Physical Therapysaba ramzanNessuna valutazione finora

- Data Lens Overview: Category Keyword CountDocumento25 pagineData Lens Overview: Category Keyword CountHari HaranNessuna valutazione finora

- Valvular Heart DiseaseDocumento73 pagineValvular Heart Diseaseindia2puppy100% (4)

- Pathogenesis of Bacterial InfectionDocumento35 paginePathogenesis of Bacterial InfectionDiyantoro NyoNessuna valutazione finora

- Pterygium & DacryocystitisDocumento45 paginePterygium & DacryocystitisAngelaTrinidadNessuna valutazione finora

- Normal Digestion / Absorption of FatDocumento5 pagineNormal Digestion / Absorption of FatMarc Michael Dela CruzNessuna valutazione finora

- Topical Oxygen Wound TherapyDocumento9 pagineTopical Oxygen Wound TherapyTony LeeNessuna valutazione finora

- Option Com - Content&view Section&layout Blog&id 3 &itemid 60 FaqsDocumento7 pagineOption Com - Content&view Section&layout Blog&id 3 &itemid 60 FaqsJig GamoloNessuna valutazione finora

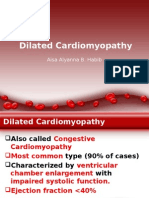

- Dilated CardiomyopathyDocumento23 pagineDilated CardiomyopathyYanna Habib-MangotaraNessuna valutazione finora

- Anatomic Therapy PDFDocumento364 pagineAnatomic Therapy PDFrahul_choubey_9Nessuna valutazione finora

- Thalassemia: SymptomsDocumento3 pagineThalassemia: SymptomsAndi BandotNessuna valutazione finora

- Make-Up Improves The Quality of Life of Acne Patients Without Aggravating Acne Eruptions During TreatmentsDocumento3 pagineMake-Up Improves The Quality of Life of Acne Patients Without Aggravating Acne Eruptions During TreatmentsfitrizeliaNessuna valutazione finora

- Cleansing and DetoxificationDocumento1 paginaCleansing and DetoxificationerosNessuna valutazione finora

- Chemical Peel Guidelines PDFDocumento1 paginaChemical Peel Guidelines PDFHasan MurdimanNessuna valutazione finora

- PONR - Comprehensive Nursing Health History and Physical ExaminationDocumento21 paginePONR - Comprehensive Nursing Health History and Physical ExaminationDRJC100% (1)

- Paces 6 - Cns - Lower LimbDocumento18 paginePaces 6 - Cns - Lower LimbDrShamshad Khan100% (1)

- Soal PTS Bahasa Inggris Kelas XiDocumento3 pagineSoal PTS Bahasa Inggris Kelas XiHafiz AriNessuna valutazione finora

- SPECIMEN COLLECTION and Processing For BACTERIOLOGY PDFDocumento19 pagineSPECIMEN COLLECTION and Processing For BACTERIOLOGY PDFLPDF010596Nessuna valutazione finora

- NCP Resiko PerdarahanDocumento3 pagineNCP Resiko PerdarahanRifky FaishalNessuna valutazione finora

- Hand Hygiene: Panitia Pengendalian Infeksi Nosokomial. Dr. Ahmad D. SudrajatDocumento40 pagineHand Hygiene: Panitia Pengendalian Infeksi Nosokomial. Dr. Ahmad D. SudrajatpedsquadNessuna valutazione finora

- Combined Orthokeratology With Atropine For Children With Myopia: A Meta-AnalysisDocumento9 pagineCombined Orthokeratology With Atropine For Children With Myopia: A Meta-AnalysiskarakuraNessuna valutazione finora

- LocalizationDocumento38 pagineLocalizationWilson HannahNessuna valutazione finora

- TN Maulana VL PalpebraeDocumento10 pagineTN Maulana VL Palpebraemonyet65Nessuna valutazione finora

- Faisal Yunus PIPKRA How Adherence To GOLD Improve The COPD Treatment and Economic Outcomes - 3 Feb 2023-1Documento37 pagineFaisal Yunus PIPKRA How Adherence To GOLD Improve The COPD Treatment and Economic Outcomes - 3 Feb 2023-1Muhammad Khairul AfifNessuna valutazione finora

- Cefuroxime, Celecoxib, ChloridineDocumento2 pagineCefuroxime, Celecoxib, ChloridinekrizzywhizzyNessuna valutazione finora

- Family Role On Schizoaffective Mixed Type Patient Treatment: Case ReportDocumento4 pagineFamily Role On Schizoaffective Mixed Type Patient Treatment: Case ReportAshNessuna valutazione finora

- Nursing Case Presentation For A Patient With CABG: Subject: Medical Surgical Nursing-IIDocumento10 pagineNursing Case Presentation For A Patient With CABG: Subject: Medical Surgical Nursing-IIanamika sharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- CHAS Brochure English Jan2014Documento2 pagineCHAS Brochure English Jan2014inabansNessuna valutazione finora