Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Admin Midterm

Caricato da

Yvonne Nicole GarbanzosDescrizione originale:

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Admin Midterm

Caricato da

Yvonne Nicole GarbanzosCopyright:

Formati disponibili

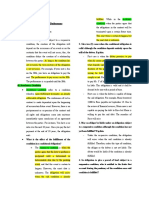

MIDTERM CASES PRINCIPLES:

EPSA V. CHR

*cited the case of Carino

ISSUE:

Does the CHR have jurisdiction to issue a writ of injunction or

restraining order against supposed violators of human rights, to compel

them to cease and desist from continuing the acts complained of?

HELD:

The constitutional provision directing the CHR to "provide for

preventive measures and legal aid services to the underprivileged

whose human rights have been violated or need protection" may not be

construed to confer jurisdiction on the Commission to issue a

restraining order or writ of injunction for, if that were the intention, the

Constitution would have expressly said so. "Jurisdiction is conferred

only by the Constitution or by law"

FABELLA V. CA

ISSUE:

Whether or not Respondent Court of Appeals committed grave

abuse of discretion in holding in effect that private respondents were

denied due process of law.

RULING:

In administrative proceedings, due process has been recognized to

include the following: (1) the right to actual or constructive notice of

the institution of proceedings which may affect a respondents legal

rights; (2) a real opportunity to be heard personally or with the

assistance of counsel, to present witnesses and evidence in ones favor,

and to defend ones rights; (3) a tribunal vested with competent

jurisdiction and so constituted as to afford a person charged

administratively a reasonable guarantee of honesty as well as

impartiality; and (4) a finding by said tribunal which is supported

by substantial evidence submitted for consideration during the hearing

or contained in the records or made known to the parties affected.[13]

In the present case, the various committees formed by DECS to

hear the administrative charges against private respondents did not

include a representative of the local or, in its absence, any existing

provincial or national teachers organization as required by Section 9

of RA 4670. Accordingly, these committees were deemed to have no

competent jurisdiction. Thus, all proceedings undertaken by them were

necessarily void. They could not provide any basis for the suspension

or dismissal of private respondents. The inclusion of a representative

of a teachers organization in these committees was indispensable to

ensure an impartial tribunal. It was this requirement that would have

given substance and meaning to the right to be heard. Indeed, in any

proceeding, the essence of procedural due process is embodied in the

basic requirement of notice and a real opportunity to be heard.[14]

LEPANTO V. CA

Respondent correctly argued that Article 82 of E.O. 226 grants the

right of appeal from decisions or final orders of the BOI and in

granting such right, it also provided where and in what manner such

appeal can be brought. These latter portions simply deal with

procedural aspects which this Court has the power to regulate by virtue

of its constitutional rule-making powers.

VAR ORIENT V. ACACOSO

Equally unmeritorious is the petitioners allegation that they were

denied due process because the decision was rendered without a

formal hearing. The essence of due process is simply an opportunity to

be heard (Bermejo v. Barrios, 31 SCRA 764), or, as applied to

administrative proceedings, an opportunity to explain ones side

(Tajonera v. Lamaroza, 110 SCRA 438; Gas Corporation of the Phil. v.

Hon. Inciong, 93 SCRA 653; Cebu Institute of Technology v. Minister

of Labor, 113 SCRA 257), or an opportunity to seek a reconsideration

of the action or ruling complained of (Dormitorio v. Fernandez, 72

SCRA 388).

The fact is that at the hearing of the case on March 4, 1987, it was

agreed by the parties that they would file their respective memoranda

and thereafter consider the case submitted for decision (Annex 7 of

Bunyogs Comment). This procedure is authorized by law to expedite

the settlement of labor disputes. However, only the private respondents

submitted memoranda. The petitioners did not. On June 10, 1987, the

respondents filed a motion to resolve (Annex 7, Bunyogs Comment).

The petitioners counsel did not oppose either the "Motion to Resolve"

or the respondents "Motion for Execution of Decision" dated October

19, 1987 (Annex 10), both of which were furnished them through

counsel. If it were true, as they now contend, that they had been

denied due process in the form of a formal hearing, they should

have opposed both motions.chanrobles virtualawlibrary

chanrobles.com:chanrobles.com.ph

UP BOARD OF REGENTS V CA

In this case, the trial court dismissed private respondent's petition

precisely on grounds of academic freedom but the Court of Appeals

reversed holding that private respondent was denied due process.

As the foregoing narration of facts in this case shows, however,

various committees had been formed to investigate the charge that

private respondent had committed plagiarism and, in all the

investigations held, she was heard in her defense. Indeed, if any

criticism may be made of the university proceedings before private

respondent was finally stripped of her degree, it is that there were too

many committee and individual investigations conducted, although all

resulted in a finding that private respondent committed dishonesty in

submitting her doctoral dissertation on the basis of which she was

conferred the Ph.D. degree.

Indeed, in administrative proceedings, the essence of due process is

simply the opportunity to explain one's side of a controversy or a

chance seek reconsideration of the action or ruling complained of.27 A

party who has availed of the opportunity to present his position cannot

tenably claim to have been denied due process.28

In this case, private respondent was informed in writing of the charges

against her29 and afforded opportunities to refute them. She was asked

to submit her written explanation, which she forwarded on September

25, 1993.30Private respondent then met with the U.P. chancellor and

the members of the Zafaralla committee to discuss her case. In

addition, she sent several letters to the U.P. authorities explaining her

position.31

VICTORIAS MILLING

Pursuant to the aforequoted provision, PPA enacted Administrative

Order No. 13-77 precisely to govern, among others, appeals from PPA

decisions. It is now finally settled that administrative rules and

regulations issued in accordance with law, like PPA Administrative

Order No. 13-77, have the force and effect of law (Valerio vs.

Secretary of Agriculture and Natural Resources, 7 SCRA 719;

Antique Sawmills, Inc. vs. Zayco, et al., 17 SCRA 316; and

Macailing vs. Andrada, 31 SCRA 126), and are binding on all

persons dealing with that body.

NICOLAS v. DESIERTO

Without proof that the head of office was negligent, no administrative

liability may attach. Indeed, the negligence of subordinates cannot

always be ascribed to their superior in the absence of evidence of the

latters own negligence.29 While Arriola might have been negligent in

accepting the spurious documents, such fact does not automatically

imply that Nicolas was also. As a matter of course, the latter relied on

the formers recommendation. Petitioner is not mandated or even

expected to verify personally from the Bureau of Customs or from

wherever else it originated each receipt or document that appears on

its face to have been regularly issued or executed.

FORTICH V CORONA

Anent the first issue, in order to determine whether the recourse of

petitioners is proper or not, it is necessary to draw a line between an

error of judgment and an error of jurisdiction. An error of

judgment is one which the court may commit in the exercise of its

jurisdiction, and which error is reviewable only by an appeal.[35] On the

other hand, an error of jurisdiction is one where the act complained

of was issued by the court, officer or a quasi-judicial

body without or in excess of jurisdiction, or with grave abuse of

discretion which is tantamount to lack or in excess of jurisdiction.

[36]

This error is correctable only by the extraordinary writ of certiorari.

and additional legal provisions that have the effect of law, should be

within the scope of the statutory authority granted by the legislature to

the administrative agency. It is required that the regulation be germane

to the objects and purposes of the law, and be not in contradiction to,

but in conformity with, the standards prescribed by law.17 They must

conform to and be consistent with the provisions of the enabling

statute in order for such rule or regulation to be valid. Constitutional

and statutory provisions control with respect to what rules and

regulations may be promulgated by an administrative body, as well as

with respect to what fields are subject to regulation by it. It may not

make rules and regulations which are inconsistent with the provisions

of the Constitution or a statute, particularly the statute it is

administering or which created it, or which are in derogation of, or

defeat, the purpose of a statute. In case of conflict between a statute

and an administrative order, the former must prevail.18

[37]

It is true that under Rule 43, appeals from awards, judgments,

final orders or resolutions of any quasi-judicial agency exercising

quasi-judicial functions,[38] including the Office of the President,

[39]

may be taken to the Court of Appeals by filing a verified petition

for review[40] within fifteen (15) days from notice of the said judgment,

final order or resolution,[41] whether the appeal involves questions of

fact, of law, or mixed questions of fact and law.[42]

SMART V NTC

Administrative agencies possess quasi-legislative or rule-making

powers and quasi-judicial or administrative adjudicatory powers.

Quasi-legislative or rule-making power is the power to make rules and

regulations which results in delegated legislation that is within the

confines of the granting statute and the doctrine of non-delegability

and separability of powers.16

The rules and regulations that administrative agencies promulgate,

which are the product of a delegated legislative power to create new

Not to be confused with the quasi-legislative or rule-making power of

an administrative agency is its quasi-judicial or administrative

adjudicatory power. This is the power to hear and determine questions

of fact to which the legislative policy is to apply and to decide in

accordance with the standards laid down by the law itself in enforcing

and administering the same law. The administrative body exercises its

quasi-judicial power when it performs in a judicial manner an act

which is essentially of an executive or administrative nature, where the

power to act in such manner is incidental to or reasonably necessary

for the performance of the executive or administrative duty entrusted

to it. In carrying out their quasi-judicial functions, the administrative

officers or bodies are required to investigate facts or ascertain the

existence of facts, hold hearings, weigh evidence, and draw

conclusions from them as basis for their official action and exercise of

discretion in a judicial nature.19

In questioning the validity or constitutionality of a rule or regulation

issued by an administrative agency, a party need not exhaust

administrative remedies before going to court. This principle applies

only where the act of the administrative agency concerned was

performed pursuant to its quasi-judicial function, and not when the

assailed act pertained to its rule-making or quasi-legislative power.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Constitutional Law ModDocumento217 pagineConstitutional Law ModEA Morr86% (7)

- Mass Surveillance ReportDocumento32 pagineMass Surveillance ReportThe Guardian100% (5)

- Sea-Land Service v. CA 357 SCRA 441Documento2 pagineSea-Land Service v. CA 357 SCRA 441Kyle DionisioNessuna valutazione finora

- Fleumer Vs HixDocumento1 paginaFleumer Vs HixYvonne Nicole GarbanzosNessuna valutazione finora

- Acance Vs CADocumento4 pagineAcance Vs CAYvonne Nicole GarbanzosNessuna valutazione finora

- 98) Aldovino Vs COMELECDocumento2 pagine98) Aldovino Vs COMELECAlexandraSoledadNessuna valutazione finora

- Tala vs. Banco FilipinoDocumento1 paginaTala vs. Banco FilipinoKarissa TolentinoNessuna valutazione finora

- 105 Bayan Vs Ermita PDFDocumento7 pagine105 Bayan Vs Ermita PDFKJPL_1987Nessuna valutazione finora

- Nasureco V NLRC DigestDocumento2 pagineNasureco V NLRC DigestFidelis Victorino QuinagoranNessuna valutazione finora

- PALE - Part I PRACTICE OF LAWDocumento5 paginePALE - Part I PRACTICE OF LAWerlaine_franciscoNessuna valutazione finora

- ScriptDocumento6 pagineScriptMiguel CastilloNessuna valutazione finora

- San Miguel Vs Sec. of LaborDocumento5 pagineSan Miguel Vs Sec. of LaborMelissa Joy OhaoNessuna valutazione finora

- 6 Republic vs. Court of Appeals 200 SCRA 226 August 05 1991Documento22 pagine6 Republic vs. Court of Appeals 200 SCRA 226 August 05 1991Raiya AngelaNessuna valutazione finora

- Bar Essay Questions 2007-2013Documento31 pagineBar Essay Questions 2007-2013Ashley CandiceNessuna valutazione finora

- Manosca v. CA, G.R. 166440, Jan. 29, 1996Documento12 pagineManosca v. CA, G.R. 166440, Jan. 29, 1996FD BalitaNessuna valutazione finora

- Admin Law Set 1Documento151 pagineAdmin Law Set 1Lee SomarNessuna valutazione finora

- Tantano V Caboverde Case DigestDocumento3 pagineTantano V Caboverde Case DigestYvonne Nicole GarbanzosNessuna valutazione finora

- Marcelo vs. BungubungDocumento18 pagineMarcelo vs. BungubungLourdes LescanoNessuna valutazione finora

- PAWIM F 018 Attendance Sheet JUNE 1Documento2 paginePAWIM F 018 Attendance Sheet JUNE 1FELIX ESMAMANessuna valutazione finora

- CH 5 - Admin LawDocumento5 pagineCH 5 - Admin Lawinagigi13Nessuna valutazione finora

- Expanded Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act of 2022Documento44 pagineExpanded Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act of 2022Michael John D. AlipioNessuna valutazione finora

- 39 To 51 VhaldigestDocumento33 pagine39 To 51 VhaldigestChristian KongNessuna valutazione finora

- Rule 131 Rules of Court PhilippinesDocumento3 pagineRule 131 Rules of Court PhilippinesArlando G. ArlandoNessuna valutazione finora

- Pre Trial and Prelim ConfDocumento5 paginePre Trial and Prelim ConfSapphireNessuna valutazione finora

- University of The Philippines Vs Hon. Ferrer-Calleja - GR 96189 - July 14, 1992Documento8 pagineUniversity of The Philippines Vs Hon. Ferrer-Calleja - GR 96189 - July 14, 1992BerniceAnneAseñas-ElmacoNessuna valutazione finora

- Gregorio Araneta University Foundation vs. NLRCDocumento13 pagineGregorio Araneta University Foundation vs. NLRCAngelica AbalosNessuna valutazione finora

- Calalang V Williams GR No. 47800 December 2, 1940 FactsDocumento7 pagineCalalang V Williams GR No. 47800 December 2, 1940 FactsemgraceNessuna valutazione finora

- Lyceum of The Philippines, Inc. vs. Court of AppealsDocumento14 pagineLyceum of The Philippines, Inc. vs. Court of AppealsKyla Ellen CalelaoNessuna valutazione finora

- 1pale Case DigestsasgDocumento20 pagine1pale Case DigestsasgShannin MaeNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Notes 2Documento66 pagineCase Notes 2Ron Jacob AlmaizNessuna valutazione finora

- People v. Murillo - Improvident Plea of GuiltDocumento2 paginePeople v. Murillo - Improvident Plea of GuiltMarvin CeledioNessuna valutazione finora

- 3 OCA vs. Judge Gonzales A.M. RTJ-16-2463Documento14 pagine3 OCA vs. Judge Gonzales A.M. RTJ-16-2463Klein ChuaNessuna valutazione finora

- Summary of Authentication of Documentary EvidenceDocumento2 pagineSummary of Authentication of Documentary Evidencejuvpilapil100% (2)

- Gonzales Vs LandbankDocumento4 pagineGonzales Vs LandbankGherald EdañoNessuna valutazione finora

- Al Amanah Islamic Investment Bank vs. CSC and N. MalbunDocumento1 paginaAl Amanah Islamic Investment Bank vs. CSC and N. Malbunc@rpe_diemNessuna valutazione finora

- Delos Reyes Vs SandiganbayanDocumento1 paginaDelos Reyes Vs Sandiganbayanmamp05Nessuna valutazione finora

- Neypes Vs CA DigestDocumento2 pagineNeypes Vs CA DigestJerome C obusanNessuna valutazione finora

- Villarama v. Court of Appeals, GR NO. 165881, Apr 19, 2006Documento10 pagineVillarama v. Court of Appeals, GR NO. 165881, Apr 19, 2006Tin LicoNessuna valutazione finora

- Compilation of Digested Cases in PALE 2Documento62 pagineCompilation of Digested Cases in PALE 2rollanekimNessuna valutazione finora

- Constitutional Law 1 - CasesDocumento22 pagineConstitutional Law 1 - CasesMaki PacificoNessuna valutazione finora

- Constitutional Law 2 Right To BailDocumento5 pagineConstitutional Law 2 Right To BailInsolent PotatoNessuna valutazione finora

- In Re Estate of BellisDocumento3 pagineIn Re Estate of BellisLucas Gabriel JohnsonNessuna valutazione finora

- Title and Definitions: Chan Robles Virtual Law LibraryDocumento36 pagineTitle and Definitions: Chan Robles Virtual Law LibrarykimNessuna valutazione finora

- 061 Padilla Rumbaua V Rumbaua PDFDocumento3 pagine061 Padilla Rumbaua V Rumbaua PDFJul A.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lateral SupportDocumento3 pagineLateral SupportGia DimayugaNessuna valutazione finora

- Air France vs. Carrascoso 18 SCRA 155 (1966)Documento8 pagineAir France vs. Carrascoso 18 SCRA 155 (1966)Fides DamascoNessuna valutazione finora

- Heirs of LumucsoDocumento2 pagineHeirs of LumucsoaudreyracelaNessuna valutazione finora

- Eusebio Vs CSCDocumento2 pagineEusebio Vs CSCApple Gee Libo-onNessuna valutazione finora

- Dimaandal v. COA Case DigestDocumento2 pagineDimaandal v. COA Case DigestCari Mangalindan MacaalayNessuna valutazione finora

- Admin-Antipolo Vs Nha DigestDocumento3 pagineAdmin-Antipolo Vs Nha DigestkatchmeifyoucannotNessuna valutazione finora

- Property MatrixDocumento2 pagineProperty MatrixDia MaeNessuna valutazione finora

- Kaisahan NG Manggagawa vs. GotamcoDocumento6 pagineKaisahan NG Manggagawa vs. GotamcoFe PortabesNessuna valutazione finora

- Antipolo Realty Corporation Vs NhaDocumento2 pagineAntipolo Realty Corporation Vs NhaReth GuevarraNessuna valutazione finora

- Invitation LetterDocumento1 paginaInvitation LetterMohibur RahmanNessuna valutazione finora

- International School Alliance of Educators Vs QuisumbingDocumento6 pagineInternational School Alliance of Educators Vs QuisumbingShane Marie CanonoNessuna valutazione finora

- AFP-RSBS vs. RP, G.R. 180086, July 2, 2014Documento2 pagineAFP-RSBS vs. RP, G.R. 180086, July 2, 2014Ron Christian EupeñaNessuna valutazione finora

- 2nd Batch ConflictDocumento80 pagine2nd Batch ConflictShericka Jade MontorNessuna valutazione finora

- Bill of Rights For Agricultural LaborDocumento3 pagineBill of Rights For Agricultural LaborElyn ApiadoNessuna valutazione finora

- Ownership To Co-OwnershipDocumento179 pagineOwnership To Co-OwnershipOnat PNessuna valutazione finora

- Oposa Vs Factoran 224 Scra 792Documento3 pagineOposa Vs Factoran 224 Scra 792Gina Ville Lagura VilchezNessuna valutazione finora

- Appeal Procedure FlowchartDocumento1 paginaAppeal Procedure FlowchartAaron ReyesNessuna valutazione finora

- Admin LawDocumento9 pagineAdmin LawSARIKANessuna valutazione finora

- Ac No. 10438Documento2 pagineAc No. 10438Xiena Marie Ysit, J.DNessuna valutazione finora

- STATCON SUMMARY OF CASES 26 34ewewewDocumento7 pagineSTATCON SUMMARY OF CASES 26 34ewewewRovelyn PamotonganNessuna valutazione finora

- Indemnification and Responsibilities of CommissionersDocumento1 paginaIndemnification and Responsibilities of CommissionersJellie ElmerNessuna valutazione finora

- Final Coaching Drills ENGLISHDocumento36 pagineFinal Coaching Drills ENGLISHJovie MasongsongNessuna valutazione finora

- Suspensive Vs ResolutoryDocumento14 pagineSuspensive Vs Resolutoryclifford tubanaNessuna valutazione finora

- NatresDocumento10 pagineNatresnicole coNessuna valutazione finora

- Wiltshire Fire Co. Vs NLRC and Vicente OngDocumento6 pagineWiltshire Fire Co. Vs NLRC and Vicente OngStephanie ValentineNessuna valutazione finora

- VH Manufacturing Vs NLRCDocumento1 paginaVH Manufacturing Vs NLRChehe kurimaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Research On PreTrialDocumento3 pagineResearch On PreTrialCzarina RubicaNessuna valutazione finora

- Epza Vs CHRDocumento4 pagineEpza Vs CHRPaul Arman MurilloNessuna valutazione finora

- Epza Vs CHRDocumento4 pagineEpza Vs CHRPaul Arman MurilloNessuna valutazione finora

- Lex Pareto Stat (Poli)Documento5 pagineLex Pareto Stat (Poli)Yvonne Nicole GarbanzosNessuna valutazione finora

- Tax 2 AssignmentDocumento1 paginaTax 2 AssignmentYvonne Nicole GarbanzosNessuna valutazione finora

- Conflict of LawsDocumento56 pagineConflict of LawsYvonne Nicole GarbanzosNessuna valutazione finora

- Yvonne Nicole C. Garbanzos LLB-3 Taxation Law Ii Taxpayer'S Remedies From Tax AssessmentDocumento1 paginaYvonne Nicole C. Garbanzos LLB-3 Taxation Law Ii Taxpayer'S Remedies From Tax AssessmentYvonne Nicole GarbanzosNessuna valutazione finora

- Advisory Opinion On NamibiaDocumento105 pagineAdvisory Opinion On NamibiaYvonne Nicole GarbanzosNessuna valutazione finora

- Torts Full Text CompiledDocumento93 pagineTorts Full Text CompiledYvonne Nicole GarbanzosNessuna valutazione finora

- Bank of America Vs American Realty Case DigestDocumento2 pagineBank of America Vs American Realty Case DigestYvonne Nicole GarbanzosNessuna valutazione finora

- WILLIAMS Et Al v. ILLINOIS UNION INSURANCE COMPANY Plaintiff Motion To Compel DocumentsDocumento25 pagineWILLIAMS Et Al v. ILLINOIS UNION INSURANCE COMPANY Plaintiff Motion To Compel DocumentsACELitigationWatchNessuna valutazione finora

- Barbara Cerullo Rivana Cerullo and David Cerullo v. Officer Todd, B.O.P. Guard Officer Perez, B.O.P. Guard Lieutenant Starr, B.O.P. W.A. Perrill, Warden, Fci Englewood Federal Bureau of Prisons United States of America T.D. Allport, Correctional Counselor, Fpc, Englewood, 69 F.3d 547, 10th Cir. (1995)Documento4 pagineBarbara Cerullo Rivana Cerullo and David Cerullo v. Officer Todd, B.O.P. Guard Officer Perez, B.O.P. Guard Lieutenant Starr, B.O.P. W.A. Perrill, Warden, Fci Englewood Federal Bureau of Prisons United States of America T.D. Allport, Correctional Counselor, Fpc, Englewood, 69 F.3d 547, 10th Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Jaravata Vs Sandiganbayan, 127 SCRA 363Documento3 pagineJaravata Vs Sandiganbayan, 127 SCRA 363AddAllNessuna valutazione finora

- Buslaw Reviewer Guide QuestionsDocumento9 pagineBuslaw Reviewer Guide QuestionsFrances Alandra SorianoNessuna valutazione finora

- Wilson Go V. Estate of Late Felisa Tamio de Buenaventura GR No. 211972, Jul 22, 2015Documento2 pagineWilson Go V. Estate of Late Felisa Tamio de Buenaventura GR No. 211972, Jul 22, 2015Alvin Ryan KipliNessuna valutazione finora

- Indian Law Report - Allahabad Series - Apr2011Documento116 pagineIndian Law Report - Allahabad Series - Apr2011PrasadNessuna valutazione finora

- Nevada Supreme Court Bail DecisionDocumento28 pagineNevada Supreme Court Bail DecisionRiley SnyderNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Briefs Contracts 2Documento92 pagineCase Briefs Contracts 2sashimimanNessuna valutazione finora

- Bacani v. Nacoco, 100 Phil. 468Documento4 pagineBacani v. Nacoco, 100 Phil. 468martina lopezNessuna valutazione finora

- United States v. Lee Roy Mullins, JR., 971 F.2d 1138, 4th Cir. (1992)Documento15 pagineUnited States v. Lee Roy Mullins, JR., 971 F.2d 1138, 4th Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Smiths Creek Masonic Lodge 491 - PrintInspectionDocumento1 paginaSmiths Creek Masonic Lodge 491 - PrintInspectionBryce AirgoodNessuna valutazione finora

- Hire and Fire - MultilawDocumento636 pagineHire and Fire - MultilawFernandoLópezNessuna valutazione finora

- Does The OMB Have Power To Directly Impose The Penalty of Removal From Office Against Public Officials? - YESDocumento4 pagineDoes The OMB Have Power To Directly Impose The Penalty of Removal From Office Against Public Officials? - YESMegan AglauaNessuna valutazione finora

- Fusepoint Power of AttorneyDocumento1 paginaFusepoint Power of AttorneyboduntayNessuna valutazione finora

- Print Rules On EvidenceDocumento56 paginePrint Rules On EvidenceAshley CandiceNessuna valutazione finora

- Right To Information and Right To KnowDocumento6 pagineRight To Information and Right To KnowTarunpaul SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Rajkiya Engineering College: Tirwa Road, Kannauj-209732 (Up)Documento2 pagineRajkiya Engineering College: Tirwa Road, Kannauj-209732 (Up)Er Insaf AliNessuna valutazione finora

- Hernandez-Escobar v. Bureau of Immigration and Customs Enforcement - Document No. 2Documento2 pagineHernandez-Escobar v. Bureau of Immigration and Customs Enforcement - Document No. 2Justia.comNessuna valutazione finora

- M-I Drilling Fluids UK v. Dynamic Air Et. Al.Documento23 pagineM-I Drilling Fluids UK v. Dynamic Air Et. Al.Patent LitigationNessuna valutazione finora

- Rubbermaid v. Centrex PlasticsDocumento6 pagineRubbermaid v. Centrex PlasticsPriorSmartNessuna valutazione finora