Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Radial Neck Fractures in Children

Caricato da

AndikaDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Radial Neck Fractures in Children

Caricato da

AndikaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery 2011;19(2):209-12

Radial neck fractures in children

Bryan Hsi Ming Tan,1 Arjandas Mahadev2

1

2

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, National University Health System, Singapore

Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, KK Womens and Childrens Hospital, Singapore

ABSTRACT

Purpose. To review records of 108 children with

radial neck fractures and develop an algorithm for

treatment.

Methods. Records of 50 girls and 58 boys aged 2 to

14 (mean, 8.7) years with radial neck fractures were

reviewed. The most common injury mechanism was

tripping and falling on an outstretched hand while

running (n=44), followed by falling from monkey bars

(n=11). Fractures were classified into grade 1 (n=25),

grade 2 (n=60), grade 3 (n=16), grade 4a (n=6), and

grade 4b (n=1). 21 patients had associated fractures

involving the olecranon, proximal ulna, and/or

the humeral supracondyle. The time from injury

to treatment ranged from 0 to 7 days. Treatments

included casting without manipulation (n=86), closed

reduction and casting (n=8), percutaneous Kirschner

wireassisted reduction and casting (n=7), and open

reduction and casting (n=7).

Results. Patients were followed up for a mean of

2.7 (range, 15) years. Outcome was excellent in 93

patients, good in 11, and fair in 4. Higher fracture grades

correlated positively with poorer outcomes (p=0.001)

and more invasive treatment (p=0.001). Nonetheless,

the post-reduction angles of all the patients were

not significantly different (p>0.05). Older children

sustained more severe fractures (p=0.04) and had

poorer outcomes, even after correction for fracture

grade (p=0.007). Patients with associated fractures

had significantly poorer outcomes (p<0.05). Two

patients developed synostosis of the proximal radioulnar joint. One of whom had an associated olecranon

fracture and underwent open reduction and casting.

The other had an associated proximal ulnar fracture

and underwent repeated percutaneous Kirschner

wireassisted reduction owing to loss of reduction.

Five patients developed heterotopic ossification.

Four of whom had associated fractures (3 involved

the olecranon and one the proximal ulna). 14 patients

developed cubitus valgus deformity of 3 to 10.

Conclusion. Open reduction should only be

performed after more conservative treatments fail to

achieve reduction.

Key words: radius fractures; complications, treatment

outcome

Address correspondence and reprint requests to: Dr Arjandas Mahadev, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, KK Womens and

Childrens Hospital, 100 Bukit Timah Road, Singapore 229899. E-mail: arjandas@yahoo.com

Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery

210 BHM Tan and A Mahadev

INTRODUCTION

Radial neck fractures account for 5 to 10% of all elbow

fractures in children.1,2 The ossification centre of the

proximal radial epiphysis usually appears at age 4

to 5 years. The physis closes at age 14 to 17 years.

Fractures through the articular surface of the radial

head are rare in children. The more common site is

through the physis (with a metaphyseal fragment,

Salter-Harris type II) or the neck.2 The epiphysis of

the radial head is completely covered with cartilage

and the blood supply enters through the metaphysis.

Avascular necrosis of the radial head is rare, as the

injury site is distal to the entry of the vessels.3

Treatment for radial neck fractures in children

varies according to the displacement, angulation,

and skeletal maturity. Most fractures are undisplaced

or minimally displaced and can be treated with

closed reduction and casting with good outcome.4,5

Severely displaced or angulated fractures often

have poorer outcomes, even after open reduction.610

Complications include pain, decreased range of

motion, cubitus valgus, radio-ulnar synostosis,

heterotopic ossification, radial head overgrowth,

premature physeal closure, avascular necrosis,

malunion,

and non-union.1,4,6,8,1115 Risk factors

associated with poor outcome include age, radial

neck angulation, associated injury, open reduction,

and internal fixation.1,13,1517 We reviewed records of

108 children with radial neck fractures and proposed

a treatment algorithm .

MATERIALS AND METHODS

ia

lh

ea

ax

Ra

dia

lh

is

n

tio

ra

d

l

Radia

shaft

RESULTS

Patients were followed up for a mean of 2.7 (range,

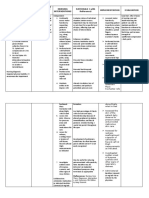

Table 1

Judet classification for radial neck fractures18

Grade

Epiphyseal tilt

1

2

3

4a

4b

ula

to

ad

ar

an

g

ul

he

ic

ead

nd

di

al

pe

Ra

Pe

r

ax

is

Records of 50 girls and 58 boys aged 2 to 14 (mean,

8.7) years with radial neck fractures who presented

between 1997 and 2001 were reviewed. 56 of the

patients injured the right arm. The most common

injury mechanism was tripping and falling on an

outstretched hand while running (n=44), followed

by falling from monkey bars (n=11). Radial head

angulation was defined as the angle between the

perpendicular of the axis of the displaced radial

epiphysis and the axis of the radial shaft (Fig. 1).

According to the Judet classification (Table 1),18

fractures were classified into grade 1 (n=25), grade 2

(n=60), grade 3 (n=16), grade 4a (n=6), and grade 4b

(n=1). 21 patients had associated fractures involving

the olecranon (n=12), the proximal ulna (n=5), the

humeral supracondyle (n=2), the olecranon and the

humeral supracondyle (n=1), and the olecranon and

proximal humerus with elbow dislocation (n=1).

The time from injury to treatment ranged from

0 to 7 days. Treatments included casting without

manipulation for a mean of 3.4 (range, 18) weeks

for those with an angulation of 0 to 40 (mean,

8) [n=86], closed reduction and casting for those

with an angulation of 30 to 59 (mean, 51) [n=8],

percutaneous Kirschner wireassisted reduction

and casting for those with an angulation of 45 to 81

(mean, 62) [n=7], and open reduction and casting for

those with an angulation 52 to 80 (mean, 65) [n=7].

Clinical outcome was evaluated in person for 79

patients and over the telephone for 29 patients (Table

2). Radiographs were assessed for complications.

Students t-test was used for comparisons between

groups. Pearsons correlation was used to determine

correlation between outcome and patient age/

fracture grade/treatment.

axis

Outcome

Excellent

Good

Fair

Figure 1 Measurement of radial head angulation.

Poor

0, with translation

<30

3060

080

8090

Table 2

Clinical outcome evaluation

Description

No pain, full range of motion, no deformity

Occasional insignificant pain, range of motion

decreased <20 in any direction, <10 valgus

deformity

Occasional insignificant pain, range of motion

decreased >20, >10 valgus deformity

Requiring further surgery

Vol. 19 No. 2, August 2011

Radial neck fractures in children 211

15) years. Clinical outcome was excellent in 94

patients, good in 10, and fair in 4. No patient had

chronic pain. Higher fracture grades correlated

positively with poorer outcomes (p=0.001, Pearsons

correlation) and more invasive treatment (p=0.001,

Pearsons correlation). Nonetheless, the postreduction angle after different treatment modalities

was not significantly different (p>0.05, t-test with

Bonferroni correction). Older children sustained more

severe fractures (grade 3 or higher) [p=0.04, t-test] and

had poorer outcomes, even after correction for fracture

grade (p=0.007, t-test, Table 3). Patients with associated

fractures had significantly poorer outcomes (p<0.05,

Pearsons correlation). Among patients with grade 3

fractures (n=16), more invasive treatment correlated

positively with poorer outcomes (p=0.006, Pearsons

correlation). Among patients with grade 4 fractures

(n=7), there was a trend toward poorer outcome after

open reduction rather than percutaneous Kirschner

wireassisted reduction (Table 4).

A 5-year-old girl with an angulation of 51 and

displacement of 50% underwent intramedullary

fixation using a Kirschner wire. The Kirschner wire

was removed after 3 weeks and casting was applied

for another 3 weeks. Two patients underwent a second

surgery within 2 weeks: one had loss of reduction at

day 2 after percutaneous Kirschner wireassisted

reduction and casting; the procedure was repeated.

The other patient had loss of reduction at week 1 after

closed reduction and casting and underwent open

reduction. Casting was applied for 4 more weeks in

both patients.

Two patients developed synostosis of the proximal

radio-ulnar joint. One of whom had an associated

olecranon fracture and underwent open reduction

and casting. The other had an associated proximal

ulnar fracture and underwent repeated percutaneous

Kirschner wireassisted reduction owing to loss

of reduction. Five patients developed heterotopic

ossification. Four of whom had associated fractures (3

involving the olecranon and one the proximal ulna).

14 patients developed cubitus valgus deformity of 3

to 10. Four patients had transient radial nerve palsy

secondary to the injury. No patient developed wound

infection, dehiscence, or avascular necrosis of the

radial head.

DISCUSSION

Mismanagement of radial neck fractures can lead to

debilitating loss of elbow function. Higher fracture

grades prognosticate poorer outcomes, regardless

of the post-reduction angle ensuing after different

treatment modalities. This suggests that factors other

than just good post-operative reduction affected

outcomes.

Older children tend to sustain more severe

fractures and have poorer outcomes. Skeletal maturity

confers a poor prognosis.1,8,13,15,16 This could be due to

the higher energy involved in the injuries in older

children. In addition, younger childrens bones are

more cartilaginous and hence more cushioned. The

energy from the trauma is more effectively absorbed,

Fracture grade

Table 3

Correlation between outcome and fracture grade/patient age

1

2

3

Patient age (years)

<5

59

>10

<5

59

>10

<5

59

>10

<5

59

>10

Outcome (no. of patients)

Excellent

Good

Fair

2

0

0

6

0

0

15

2

0

9

0

0

32

1

0

15

3

0

1

0

0

5

1

0

6

1

2

0

0

0

2

1

1

1

1

1

Fracture grade

Table 4

Correlation between outcome and fracture grade/treatment

2

3

Treatment

Outcome (no. of

patients)

Excellent

Good

Fair

Casting

Casting

Casting

Closed

Percutaneous

Open

Percutaneous

Open

without

without

without

reduction

Kirschner

reduction

Kirschner

reduction

manipulation manipulation manipulation and casting wireassisted and casting wireassisted and casting

reduction

reduction

and casting

and casting

26

2

0

53

4

0

0

1

0

7

1

0

2

1

1

2

0

1

2

1

0

1

1

2

Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery

212 BHM Tan and A Mahadev

Radial neck fractures

Angulation of <45

Angulation of >45

Casting without

manipulation

Closed reduction and casting

If unsuccessful, then

percutaneous Kirschner

wireassisted reduction and

casting

If unsuccessful, then open

reduction and casting

Figure 2 Treatment algorithm.

resulting in less severe fractures. The bone also has

greater remodelling potential and hence can achieve

better outcomes.

Radial neck fractures associated with other

fractures generally indicate higher energy

trauma.1,8,13,15,16 This may be attributed to more softtissue injury and poorer outcomes. Poorer outcomes

can be caused by complications (proximal radio-ulnar

synostosis and heterotopic ossification), which often

result in restriction of range of motion or cubitus

deformity.1,4,6,8,1114,19

The associations between heterotopic ossification

and patient age, fracture grade, and the number

and types of surgeries performed remain unclear.

Nonetheless, the association between heterotopic

ossification and associated fractures was strong, as

was the association between heterotopic ossification

and elbow dislocation.20

Synostosis of the proximal radio-ulnar joint is a

debilitating complication. An association between

radio-ulnar synostosis and open surgery has been

reported,1,4,6,8,1114,19 as open surgery and repeated

percutaneous levering causes iatrogenic disruption

of the periosteum and surrounding soft tissues and

results in disorganised callus forming synostosis. In

our study, the 2 patients who developed synostosis

of the proximal radio-ulnar joint were aged >7 years

and had associated fractures and underwent open

surgery for grades 3 and 4 fractures.

To avoid debilitating complications, we propose

a step-wise level of invasiveness protocol (Fig. 2).

Patients with undisplaced fractures or displaced

fractures with <45 angulation should be treated

with casting without manipulation. For those with

angulation of >45, closed reduction should be

attempted. When closed reduction fails, percutaneous

Kirschner wireassisted reduction under general

anaesthesia should be attempted, failing which open

reduction and cross wiring should be performed.

REFERENCES

1.

2.

3.

4.

Rockwood CA, Wilkins KE, King RE. Fractures in children. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1991:72851.

Tachdjian MO. Pediatric orthopedics. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1972.

Rang M. Childrens fractures. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1974.

Dsouza S, Vaishya R, Klenerman L. Management of radial neck fractures in children: a retrospective analysis of one

hundred patients. J Pediatr Orthop 1993;13:2328.

5. Jeffery CC. Fractures of the head of the radius in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1950;32:31424.

6. Waters PM, Stewart SL. Radial neck fracture nonunion in children. J Pediatr Orthop 2001;21:5706.

7. Metaizeau JP, Lascombes P, Lemelle JL, Finlayson D, Prevot J. Reduction and fixation of displaced radial neck fractures by

closed intramedullary pinning. J Pediatr Orthop 1993;13:35560.

8. Newman JH. Displaced radial neck fractures in children. Injury 1977;9:11421.

9. Rodgers WB, Waters PM, Hall JE. Chronic Monteggia lesions in children. Complications and results of reconstruction. J

Bone Joint Surg Am 1996;78:13229.

10. Vahvanen V, Gripenberg L. Fracture of the radial neck in children. A long-term follow-up study of 43 cases. Acta Orthop

Scand 1978;49:328.

11. Jones ER, Esah M. Displaced fractures of the neck of the radius in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1971;53:42939.

12. Steinberg EL, Golomb D, Salama R, Wientroub S. Radial head and neck fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop 1988;8:3540.

13. Gao GX, Zhang RY. Radial neck fracture in children. Chin Med J (Engl) 1984;97:8936.

14. Young S, Letts M, Jarvis J. Avascular necrosis of the radial head in children. J Pediatr Orthop 2000;20:158.

15. Evans MC, Graham HK. Radial neck fractures in children: a management algorithm. J Pediatr Orthop B 1999;8:939.

16. Steele JA, Graham HK. Angulated radial neck fractures in children. A prospective study of percutaneous reduction. J Bone

Joint Surg Br 1992;74:7604.

17. Tibone JE, Stoltz M. Fractures of the radial head and neck in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1981;63:1006.

18. Judet H, Judet J. Fractures and orthopedique de l enfant. Paris: Maloine; 1974:319.

19. Radomisli TE, Rosen AL. Controversies regarding radial neck fractures in children. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1998;353:309.

20. Ilahi OA, Strausser DW, Gabel GT. Post-traumatic heterotopic ossification about the elbow. Orthopedics 1998;21:2658.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Radial Neck Fractures in ChildrenDocumento4 pagineRadial Neck Fractures in ChildrenAnonymous 1GSeSV0Nessuna valutazione finora

- Percutaneaus Kirschner-Wire Fixation For Displaced Distal Forearm Fractures in ChildrenDocumento5 paginePercutaneaus Kirschner-Wire Fixation For Displaced Distal Forearm Fractures in ChildrennaluphmickeyNessuna valutazione finora

- 02 - Krishna ReddyDocumento7 pagine02 - Krishna ReddyAnonymous ygv5h1MRNessuna valutazione finora

- A Study On Management of Bothbones Forearm Fractures With Dynamic Compression PlateDocumento5 pagineA Study On Management of Bothbones Forearm Fractures With Dynamic Compression PlateIOSRjournalNessuna valutazione finora

- 義大醫學雜誌 - 78 - Non-periarticular locking plates for complicated and - or geriatric olecranon fractures - V2Documento17 pagine義大醫學雜誌 - 78 - Non-periarticular locking plates for complicated and - or geriatric olecranon fractures - V2bigben9262Nessuna valutazione finora

- Closed Reduction and External Fixation For Displaced Proximal Humeral FracturesDocumento4 pagineClosed Reduction and External Fixation For Displaced Proximal Humeral FracturesJhensczy Hazel Maye AlbaNessuna valutazione finora

- Comparative Study of Proximal Humerus Fractures Treated With Percutaneous Pinning and Augmented by External FixatorDocumento3 pagineComparative Study of Proximal Humerus Fractures Treated With Percutaneous Pinning and Augmented by External FixatorRahul ReddyNessuna valutazione finora

- Tur CicaDocumento8 pagineTur CicazubayetarkoNessuna valutazione finora

- Bahan Jurnal Neglected Fractures of FemurDocumento5 pagineBahan Jurnal Neglected Fractures of Femurgulamg21Nessuna valutazione finora

- Fraktur Tibia Distal Pada AnakDocumento5 pagineFraktur Tibia Distal Pada Anakarditya putra HNessuna valutazione finora

- DL TPSFDocumento5 pagineDL TPSFPramod N KNessuna valutazione finora

- Functional Outcome After The Conservative Management of A Fracture of The Distal HumerusDocumento7 pagineFunctional Outcome After The Conservative Management of A Fracture of The Distal HumerusnireguiNessuna valutazione finora

- The Clinical Outcome After Extra-Articular Colles Fractures With Simultaneous Moderate Scapholunate DissociationDocumento5 pagineThe Clinical Outcome After Extra-Articular Colles Fractures With Simultaneous Moderate Scapholunate DissociationYina Marcela Quintero OrtegaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ijos ArticleDocumento5 pagineIjos ArticleReena RaiNessuna valutazione finora

- FR GaleazziDocumento3 pagineFR GaleazziAnnisa RahimNessuna valutazione finora

- Seguimiento A 5 Años PTGH ReversaDocumento7 pagineSeguimiento A 5 Años PTGH Reversamarcelogascon.oNessuna valutazione finora

- Dynamic HIP Screw Vs Proximal Trochanteric Contoured Plate in Proximal End Fractures of FemurDocumento8 pagineDynamic HIP Screw Vs Proximal Trochanteric Contoured Plate in Proximal End Fractures of FemurKrishna CaitanyaNessuna valutazione finora

- Treatment Distal Radius Fracture With Volar Buttre PDFDocumento5 pagineTreatment Distal Radius Fracture With Volar Buttre PDFZia Ur RehmanNessuna valutazione finora

- 2023 JOT Radiological and Long Term Functional Outcomes of Displaced Distal Clavicle FracturesDocumento7 pagine2023 JOT Radiological and Long Term Functional Outcomes of Displaced Distal Clavicle FracturesjcmarecauxlNessuna valutazione finora

- 08 Subasi NecmiogluDocumento7 pagine08 Subasi Necmiogludoos1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Gyaneshwar Tonk-Anatomical and Functional EvaluationDocumento11 pagineGyaneshwar Tonk-Anatomical and Functional EvaluationchinmayghaisasNessuna valutazione finora

- Dloen-Treatment Diaphyseal Non Union Unal RadiusDocumento7 pagineDloen-Treatment Diaphyseal Non Union Unal RadiusAngélica RamírezNessuna valutazione finora

- Long Term Outcome of Isolated DiaphysealDocumento5 pagineLong Term Outcome of Isolated DiaphysealVIDevAryanNessuna valutazione finora

- To Evaluate The Functional Outcome of Volar Plating in Distal End Radius FracturesDocumento11 pagineTo Evaluate The Functional Outcome of Volar Plating in Distal End Radius FracturesIJAR JOURNALNessuna valutazione finora

- 10 1016@j Jse 2019 10 013Documento12 pagine10 1016@j Jse 2019 10 013Gustavo BECERRA PERDOMONessuna valutazione finora

- Paper 4. Study of Intra-Articular Distal End Radius EJMCMDocumento9 paginePaper 4. Study of Intra-Articular Distal End Radius EJMCMNaveen SathyanNessuna valutazione finora

- ContentServer AspDocumento7 pagineContentServer AspCoralonNessuna valutazione finora

- Magnetic BBDocumento7 pagineMagnetic BBVicente ContrerasNessuna valutazione finora

- 02-Chalidis Et AlDocumento5 pagine02-Chalidis Et AlRobert RaodNessuna valutazione finora

- Open Reduction and Internal Fixation ORIF of ComplDocumento6 pagineOpen Reduction and Internal Fixation ORIF of ComplAnnisa AnggrainiNessuna valutazione finora

- Journal Reading: Dr. Firdaus RamliDocumento22 pagineJournal Reading: Dr. Firdaus RamliBell SwanNessuna valutazione finora

- Ulnar Stiloid K - R - N - N e - Lik Etti - I Distal Radius K - R - Klar - N - N de - Erlendirilmesinde Yeni Bir Indeks (#191560) - 169235Documento5 pagineUlnar Stiloid K - R - N - N e - Lik Etti - I Distal Radius K - R - Klar - N - N de - Erlendirilmesinde Yeni Bir Indeks (#191560) - 169235Christopher Freddy Bermeo RiveraNessuna valutazione finora

- Jurnal Fraktur Humerus DistalDocumento5 pagineJurnal Fraktur Humerus DistalthisisangieNessuna valutazione finora

- Closed Treatment of Displaced Middle-Third Fractures of The Clavicle Gives Poor ResultsDocumento3 pagineClosed Treatment of Displaced Middle-Third Fractures of The Clavicle Gives Poor ResultsYulya Indi KrisnaNessuna valutazione finora

- Intramedullary Nailing of Subtrochanteric Fractures: Does Malreduction Matter?Documento5 pagineIntramedullary Nailing of Subtrochanteric Fractures: Does Malreduction Matter?Reza ParkerNessuna valutazione finora

- Mallet Finger Suturing TechniqueDocumento5 pagineMallet Finger Suturing TechniqueSivaprasath JaganathanNessuna valutazione finora

- Femoral Fractures in Children: Surgical Treatment. Miguel Marí Beltrán, Manuel Gutierres, Nelson Amorim, Sérgio Silva, JorgeCoutinho, Gilberto CostaDocumento5 pagineFemoral Fractures in Children: Surgical Treatment. Miguel Marí Beltrán, Manuel Gutierres, Nelson Amorim, Sérgio Silva, JorgeCoutinho, Gilberto CostaNuno Craveiro LopesNessuna valutazione finora

- Spori ArticleDocumento12 pagineSpori ArticleKyla Agbon ArbaniaNessuna valutazione finora

- Stabilization of Distal Humerus Fractures by Precontoured Bi-Condylar Plating in A 90-90 PatternDocumento5 pagineStabilization of Distal Humerus Fractures by Precontoured Bi-Condylar Plating in A 90-90 PatternmayNessuna valutazione finora

- Artrosis Glenohumeral Despues de Artroscopia Bankart Repair A Long-Term Follow-Up of 13 YearsDocumento6 pagineArtrosis Glenohumeral Despues de Artroscopia Bankart Repair A Long-Term Follow-Up of 13 Yearsmarcelogascon.oNessuna valutazione finora

- Panoramic Radiographic Examination: A Survey of 271 Edentulous PatientsDocumento3 paginePanoramic Radiographic Examination: A Survey of 271 Edentulous PatientskittumdsNessuna valutazione finora

- Analysis of Surgical Management of Proximal Humeral FracturesDocumento5 pagineAnalysis of Surgical Management of Proximal Humeral FracturesRhizka djitmauNessuna valutazione finora

- Surgically Assisted Rapid Maxillary Expansion Compared With Orthopedic Rapid Maxillary ExpansionDocumento7 pagineSurgically Assisted Rapid Maxillary Expansion Compared With Orthopedic Rapid Maxillary ExpansionmanalrawhiNessuna valutazione finora

- Definingnoptimal Calcar Screw Positioning in Proximal Humerus Fracture FixationDocumento7 pagineDefiningnoptimal Calcar Screw Positioning in Proximal Humerus Fracture FixationAJ CésarNessuna valutazione finora

- Evaluation of Functional Outcome of Surgical Management of Intra-Articular Calcaneum FractureDocumento23 pagineEvaluation of Functional Outcome of Surgical Management of Intra-Articular Calcaneum FractureInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNessuna valutazione finora

- Semiconstrained Total Elbow Arthroplasty-1Documento6 pagineSemiconstrained Total Elbow Arthroplasty-1Ευαγγελια ΚιμπαρηNessuna valutazione finora

- Nonoperative Treatment Compared With Plate Fixation of Displaced Midshaft Clavicular FracturesDocumento10 pagineNonoperative Treatment Compared With Plate Fixation of Displaced Midshaft Clavicular FracturesDona Ratna SariNessuna valutazione finora

- Operative Treatment of Terrible Triad of TheDocumento8 pagineOperative Treatment of Terrible Triad of TheAndrea OsborneNessuna valutazione finora

- Canine ImpactionDocumento4 pagineCanine ImpactionPorcupine TreeNessuna valutazione finora

- Anehosur Et Al 2020 Concepts and Challenges in The Surgical Management of Edentulous Mandible Fractures A Case SeriesDocumento7 pagineAnehosur Et Al 2020 Concepts and Challenges in The Surgical Management of Edentulous Mandible Fractures A Case SeriesHenry Adhy SantosoNessuna valutazione finora

- Vol29 - No2 - 59 - 63Documento5 pagineVol29 - No2 - 59 - 63Kagiso Gigfreak Urban RoccoNessuna valutazione finora

- Paper 38Documento6 paginePaper 38Dr Vineet KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Apical Root Resorption of Incisors After Orthodontic Treatment of Impacted Maxillary Canines, Radiographic StudyDocumento9 pagineApical Root Resorption of Incisors After Orthodontic Treatment of Impacted Maxillary Canines, Radiographic StudyJose CollazosNessuna valutazione finora

- Distal Femur Fractures Fixation by Locking Compression Plate-Assessment of Outcome by Rasmussens Functional Knee ScoreDocumento7 pagineDistal Femur Fractures Fixation by Locking Compression Plate-Assessment of Outcome by Rasmussens Functional Knee ScoreIJAR JOURNALNessuna valutazione finora

- 2005 Jpo Distraction For Bayne Type 4Documento5 pagine2005 Jpo Distraction For Bayne Type 4MeetJainNessuna valutazione finora

- Fractures of the Wrist: A Clinical CasebookDa EverandFractures of the Wrist: A Clinical CasebookNirmal C. TejwaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis: MSC Otho, MRCS Assistant Lecturer of Orthopaedic at Ain Shams UniversityDocumento30 pagineSlipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis: MSC Otho, MRCS Assistant Lecturer of Orthopaedic at Ain Shams UniversityBell Swan100% (1)

- Jain Extrapleural ApproachDocumento5 pagineJain Extrapleural ApproachOj AlimbuyuguenNessuna valutazione finora

- Pedicle Screw Fixation in Fracture of Thoraco-Lumbar SpineDocumento21 paginePedicle Screw Fixation in Fracture of Thoraco-Lumbar SpineNiyati SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sauve KapandjiDocumento3 pagineSauve KapandjiZieky YoansyahNessuna valutazione finora

- 1_a_Hypospadias_International_Score(1)Documento1 pagina1_a_Hypospadias_International_Score(1)AndikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Laplant 2018Documento14 pagineLaplant 2018AndikaNessuna valutazione finora

- MEC Clinical Privilege FormsDocumento46 pagineMEC Clinical Privilege FormsAndikaNessuna valutazione finora

- 729.fullDocumento11 pagine729.fullAndikaNessuna valutazione finora

- FST Annual Conference 2023 Abstract GuidelinesDocumento3 pagineFST Annual Conference 2023 Abstract GuidelinesAndikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Rectal Prolapse Following Posterior Sagittal Anorectoplasty For Anorectal MalformationsDocumento5 pagineRectal Prolapse Following Posterior Sagittal Anorectoplasty For Anorectal MalformationsAndikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Saluja 2017Documento6 pagineSaluja 2017AndikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Accepted Manuscript: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.03.021Documento23 pagineAccepted Manuscript: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.03.021AndikaNessuna valutazione finora

- 10 1016@j Jpedsurg 2019 01 040Documento14 pagine10 1016@j Jpedsurg 2019 01 040AndikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Bulan Pebruari 2008 Bulan Maret 2008 No Tanggal Nama Umur Diagnosis Ket No Tanggal Nama Umur Diagnosis KetDocumento38 pagineBulan Pebruari 2008 Bulan Maret 2008 No Tanggal Nama Umur Diagnosis Ket No Tanggal Nama Umur Diagnosis KetAndikaNessuna valutazione finora

- AfrJPaediatrSurg122119-3052943 082849 PDFDocumento3 pagineAfrJPaediatrSurg122119-3052943 082849 PDFAndikaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Diagnosis of Appendicitis in Children: Outcomes of A Strategy Based On Pediatric Surgical EvaluationDocumento8 pagineThe Diagnosis of Appendicitis in Children: Outcomes of A Strategy Based On Pediatric Surgical EvaluationAndikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Management of Fecal Incontinence: Andrea Bischoff January 21, 2021Documento32 pagineManagement of Fecal Incontinence: Andrea Bischoff January 21, 2021AndikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Functional Outcomes of Patients With Short-Segment Hirschsprung Disease After Transanal Endorectal Pull-ThroughDocumento6 pagineFunctional Outcomes of Patients With Short-Segment Hirschsprung Disease After Transanal Endorectal Pull-ThroughAndikaNessuna valutazione finora

- Retroperitoneal Teratomas in Children: Amit Chaudhary, Samir Misra, Ashish Wakhlu, R.K. Tandon and A.K. WakhluDocumento3 pagineRetroperitoneal Teratomas in Children: Amit Chaudhary, Samir Misra, Ashish Wakhlu, R.K. Tandon and A.K. WakhluAndikaNessuna valutazione finora

- COT DEMO PresentationDocumento39 pagineCOT DEMO PresentationResa Consigna MagusaraNessuna valutazione finora

- Fracture Treatment ProtocolsDocumento14 pagineFracture Treatment ProtocolsZikrul IdyaNessuna valutazione finora

- MSK Pat Tut1 Ahmad Darimi Bin MD Ariffin 2021887676Documento10 pagineMSK Pat Tut1 Ahmad Darimi Bin MD Ariffin 2021887676NIK MOHAMAD SHAKIR NIK YUSOFNessuna valutazione finora

- Anatomy and Biomechanics of The ElbowDocumento14 pagineAnatomy and Biomechanics of The ElbowAnonymous LnWIBo1G100% (1)

- Flexibility Guide PDFDocumento11 pagineFlexibility Guide PDFmunichrangers100% (1)

- Handbook of Bird Biology - CH 4Documento4 pagineHandbook of Bird Biology - CH 4butylacetateNessuna valutazione finora

- Baseline Push Pull Dynamometer User ManualDocumento16 pagineBaseline Push Pull Dynamometer User Manualphcproducts100% (4)

- ECSC Personal Injury Cases 2000 2017 December 3 2018 FinalDocumento298 pagineECSC Personal Injury Cases 2000 2017 December 3 2018 FinalYetiNessuna valutazione finora

- Cervical RadiculopathyDocumento18 pagineCervical Radiculopathyprince singhNessuna valutazione finora

- Hospital Presentation TellaDocumento27 pagineHospital Presentation TellaOlalekan TellaNessuna valutazione finora

- An Breast and PectoralisDocumento36 pagineAn Breast and PectoralisTom TsouNessuna valutazione finora

- Impaired Physical Mobility R/T Neuromuscular ImpairmentDocumento3 pagineImpaired Physical Mobility R/T Neuromuscular ImpairmentjisooNessuna valutazione finora

- Instability Procedure: of Ankle and TreatedDocumento3 pagineInstability Procedure: of Ankle and TreatedKrishna CaitanyaNessuna valutazione finora

- TMJ AnkylosisDocumento66 pagineTMJ Ankylosisumesh dombale100% (1)

- Joints Movements in Planes and AxesDocumento1 paginaJoints Movements in Planes and AxesNaveera GhouriNessuna valutazione finora

- Full Body Workout B PDFDocumento16 pagineFull Body Workout B PDFsmooth50% (2)

- ScapulaDocumento18 pagineScapulaAnkit VashistNessuna valutazione finora

- Osteoporosis, Osteomyellitis, Etc Up To EndDocumento39 pagineOsteoporosis, Osteomyellitis, Etc Up To EndJordz PlaciNessuna valutazione finora

- Physiotherapy Treatment in Plantar Fasciitis: A Case Report: January 2015Documento6 paginePhysiotherapy Treatment in Plantar Fasciitis: A Case Report: January 2015ayuNessuna valutazione finora

- Postural Analysis GuideDocumento2 paginePostural Analysis Guidekarl24100% (2)

- Presentation GoodridgeDocumento103 paginePresentation GoodridgeAlexandra Papp67% (3)

- Finger Sprain: Active Finger Flexion ExercisesDocumento7 pagineFinger Sprain: Active Finger Flexion ExercisesTJPlayzNessuna valutazione finora

- Foot Drop: Where, Why and What To Do?: ReviewDocumento13 pagineFoot Drop: Where, Why and What To Do?: ReviewFrancisco Escobar MoralesNessuna valutazione finora

- Foot and Neck Reflexiology Points For Relieving Back PainDocumento22 pagineFoot and Neck Reflexiology Points For Relieving Back PainjosenjanieNessuna valutazione finora

- Mobility Training For The Young Athlete.4Documento7 pagineMobility Training For The Young Athlete.4Dân NguyễnNessuna valutazione finora

- Intertrochanteric Femur Fracture: Attum B, Pilson HDocumento6 pagineIntertrochanteric Femur Fracture: Attum B, Pilson HEduardo Anaya DuranNessuna valutazione finora

- Infraspinatus Muscle AtrophyDocumento4 pagineInfraspinatus Muscle AtrophysudersonNessuna valutazione finora

- Pier Paolo Maria Menchetti-Cervical Spine - Minimally Invasive and Open Surgery-Springer International Publishing (2015) PDFDocumento258 paginePier Paolo Maria Menchetti-Cervical Spine - Minimally Invasive and Open Surgery-Springer International Publishing (2015) PDFLorena BurdujocNessuna valutazione finora

- Stockard Tests UE & LE TDocumento4 pagineStockard Tests UE & LE TLinh HoangNessuna valutazione finora

- (H.a.) Chapter 14 - Musculoskeletal SystemDocumento9 pagine(H.a.) Chapter 14 - Musculoskeletal SystemLevi Sebastian T. CabiguinNessuna valutazione finora