Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Polytonality Parrott

Caricato da

r-c-a-d0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

32 visualizzazioni3 paginePolytonality Parrott

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

PDF, TXT o leggi online da Scribd

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoPolytonality Parrott

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

0 valutazioniIl 0% ha trovato utile questo documento (0 voti)

32 visualizzazioni3 paginePolytonality Parrott

Caricato da

r-c-a-dPolytonality Parrott

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Formati disponibili

Scarica in formato PDF, TXT o leggi online su Scribd

Sei sulla pagina 1di 3

Polytonality

Author(s): Ian Parrott

Source: The Musical Times, Vol. 79, No. 1148 (Oct., 1938), pp. 775-776

Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd.

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/923794 .

Accessed: 17/02/2015 23:44

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Musical Times Publications Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The

Musical Times.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 130.126.162.126 on Tue, 17 Feb 2015 23:44:40 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

October 1938

THE MUSICA L TIMES

of listeners seem to derive satisfaction from its

performance; besides which it will be said by some

that Bach belongs to a past period and sentiment

changes with time.

There is, however, another reason why the standard

established by Bach has not been maintained or

proportionately advanced, and for this we must look

to the special circumstances in which the organ finds

its more usual employment-in

religious services.

We cannot blame organists for adjusting themselves

to requirements, for adjustment is at the root of peace.

A religious service is necessarily restricted in its

emotional scope, and since in addition all classes

of intelligence have to be considered there must also

be a limit to the complexity of any of its adjuncts.

In other words, the music must be easily comprehended, and this naturally influences the organist

both in the standard of performance and in the

selection of his repertory. Specific tastes and

flavours are certainly associated with varieties of

religious thought, but in emotional range and complexity of style a limitation will always be demanded

of the musical adjunct.

Thus until the organ itself developed an enlarged

mechanical constitution and the old types of pipe

received numerous attractive additions there was

no incentive to extend the potentialities of organ

music outside the staid boundaries set by the religious

service. The organ virtually suggested Sunday. There

were opportunities, it is true, when transcriptions

of Handel choruses or the lighter class of composition

that crossed the Channel from France were readily

and g'adly accepted, but the use of these was generally

confined to occasions when congregations were making

for the doors.

This led up to the time when the rendering of

familiar orchestral pieces revealed possibilities

suggesting for the instrument a destiny more ambitious than had hitherto been contemplated, and organ

recitals began to attract a wider public.

But the unexpected happened. When the silent

film called for something that would provide the

richness of orchestral volume, the flavour of ordinarylevel emotions, and all at a reasonable expense of

running costs, the answer was what someone described

as the 'nauseous degradation' of the American

cinema organ. Whether that observation was wit

or wisdom, opinion or prejudice, does not come

into the present subject. All that concerns us is

that a vast number of people to-day would describe

an organ as an instrument for reproducing every

familiar style of tune and dance in a tonal costume

that does not oppress by its dignity. In this connection it should be acknowledged that performers

on this type of instrument do not claim that they are

advancing the natural development of organ music;

they purvey what is obviously appreciated.

One may now ask what is or may be the natural

development of organ music. In music for the other

prominent instruments development has proceeded

by way of emotional expansion, the nature of each

instrument determining the range that is suitable

to it. Every organist is aware of the emotional

expansion introduced by Rheinberger, and how

with a basic adherence to the modified cyclic forms,

common property in his day, he moulded them to

the particular tonal features characteristic of the

organ. This was undoubtedly natural progress.

In the circumstances it was not to be expected that

music would show an advance through the organ,

but at all events the old reproach of stagnation was

removed. It meant a great deal more than extending

the repertory by transplanting the musical style

of other instruments, apt and happy as at times

that can be. Hence the high importance of Rheinberger's contribution.

When we consider what progress since his time has

brought distinction to organ music, we are unfor-

775

tunately compelled to admit that expansion has been

handicapped by the conditions governing the use

of the instrument which were mentioned at the

outset. Prominent composers have to a large extent

confined their attention to Preludes, Fugues, Chorals

and Voluntaries because these appropriately served

requirements, whereas works of wider appeal would

This brought

possibly have been held inconsistent.

with it the drawback that the framework of such

pieces relied on formulae which facilitated the process

of composition with consequent loss of inspiration.

Only, or chiefly, in lighter and slighter works has

the individuality of the organ been successfully

unfolded.

The present century is too close to us to justify

a final appraisement of what has recently been

produced. The worst that can with any justice

be said is that the prevailing tendency to force the

exploitation of complicated texture has not passed

organ music by without leaving an impression. It

is always tempting to find in excitement a substitute

for value. But there have been definitely encouraging

signs and the impetus behind these does not seem

to have exhausted itself.

With regard to public response, there is no doubt

that the cinema use of the organ has lured away the

attention of many who might have become more

interested in the wider possibilities of traditional

expansion, and it is to be feared that this has also

unfavourably affected the outlook of some organists

and disheartened their ambition to follow the higher

road. Popularity often offers an easy gradient with

plenty of elbow room, whereas progress is ever a

narrow path.

If we must get away from the restrictions of the

religious service, the only alternative is the public

organ such as the larger towns are providing with

increasing frequency. Even here we may find

conditions that are dispiriting and we must live

down the despondency which is inclined to possess

us when a large building is but sparsely occupied.

The best effects of an adequate organ can only be

realized in a large space, and we must persuade

ourselves that our enjoyment does not at all depend

on the numbers who sit around us. The principle

of filling the building with sounds that do credit to

our purpose must not give way to that of filling the

seats with all and sundry. With our present wealth

of capable performers, in several instances exceptional

performers, we surely have a good chance of establishing the organ on an equality with the other instruments. But we must entertain a wider outlook on

the domain of expression in which the organ can

fitly engage, and obtain some release from the many

conventions that have almost encrusted its reputation.

This is a task which will have to be shared by composers and executants alike.-Yours, &c.,

Gerrard's Cross.

PERCY RIDEOUT.

Polytonality

SIR,-If I may further continue the controversy,

is not the difficulty of Mr. Humphrey Searle and

myself in agreeing about polytonality due to the

fact that he thinks harmonically, whereas I think

melodically ? I did not say that several parts in

different keys can be combined on equal terms; I

meant that different keys could be suggested melodically, the interest depending on the movement of the

music. Mr. Searle seems to wish to stop the music and

analyse each harmonic effect, the chords apparently

suggesting keys. 'The resultant key, so to speak,'

as Mr. Searle puts it, 'may be quite different from

that in which any of the parts seem to be.' This may

well be the case for a short time, but a satisfactory

polytonal effect depends on the continual shifting

of the (key-) centre of interest, which is achieved

(melodically) by one part becoming in turn more

This content downloaded from 130.126.162.126 on Tue, 17 Feb 2015 23:44:40 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE MUSICAL TIMES

776

important than another. Mr. Searle has only to

listen to a series of diminished sevenths to realize

that not all chords suggest keys.

I agree that there is a great deal of music (even by

Bart6k) which is polytonal only on paper; I am

defending that which appeals to the ear.-Yours,

&c.,

IAN PARROTT.

Great Malvern.

Pianists'Tone Control: Also Conductors'

Time Control

SIR,-There is a general opinion among pianists

that they control tone, and among sailors that weather

depends on the phases of the moon; but opinion is

not proof. There is, so far, no evidence of tonecontrol. Until some exists, Mr. Wearman's elaborate

experiments seem premature.

Some hearers with their backs turned might listen

to notes of all loudnesses played by a pianist with

one artistic finger, and by someone else with a

poker. If they could tell which notes had special

tones, there would be something to investigate.

A conductor settles the time at starting, but,

unless a change of time at some point is expected

Notes

"Suppose

by the players, it is difficult to see how he can get it.

The players are dominated as a body by the swing

of the rhythm, and, unless they play by heart, have

to keep their eyes on their parts. If the conductor

unexpectedly quickens his beat, it must get perceptibly out of step before the players can notice it;

and in order to get into step with it they must play

actually faster than the beat. But the players do

not keep their eyes on the baton bar by bar; and

the eye, unlike the ear, has no sense of rhythm. In

France, the conductor makes a very long pause

after Fate's fourth knock at the door-almost

long

enough to go to sleep again-but the players expect

it, and watch him at that point.

On the other hand, it is wonderful that an orchestra

can accompany a solo singer. When a circus-horse

dances to music, success is due to the members of

the band watching the artist's feet. Perhaps

orchestral players follow the singer in a similar way

without the intermediation of the conductor. Mr.

Shore has told us odd facts about the orchestra;

perhaps some conductor will explain authoritatively

the secrets of his telepathy.-Yours,

&c.,

J. SWINBURNE.

News

and

St. Michael's Singers

The Annual Festival will take place at St. Michael's,

Cornhill, on November 14-19, the five-days scheme

being as follows: Haydn's Te Deum and Mozart's

Mass in C minor; a Bach organ recital by Harold

Darke; Magnificat from Byrd's 'Great' Service,

Tomkins's ' When David heard,' Purcell's ' Benedicite,' Carissimi's ' Jephtha,' Kodaly's ' Jesus and

the Traders,' Bach's 'The Spirit also helpeth us ' ;

Faur6's Requiem, Rootham's 'Brown Earth,' Bax's

' St. Patrick's Breastplate'; ' Samson' (at St.

The soloists include Elsie

Martin-in-the-Fields).

Suddaby, Isobel Baillie, Grace Bodey, Jan van der

Gucht, Edward Reach, and Norman Walker;

G. Thalben-Ball and W. H. Harris;

organists:

conductor, Harold Darke. The hour is 6, except for

'Samson' (5.30).

October 1938

Dutch Honour for English Journalist

Mr. Herbert Antcliffe's friends will be glad to hear

that his work for music in Holland has been recognized

in the Honours List issued in connection with the

fortieth anniversary of Queen Wilhelmina's reign. He

has been made a Ridder of the Order of Orange

Nassau-a title equivalent to an English knighthood.

It is rarely conferred on foreigners, and the only other

non-Dutch recipient on this occasion was Dr. F. M.

Huebner, a well-known German writer on philosophy.

Mr. Stewart Macpherson will lecture at the Royal

Institution of Great Britain (21 Albemarle Street,

W.1) on the four Saturday afternoons in November

at 3, his subject being the music of Brahms, TchaikovTickets (single lecture, 3s.; the

sky and Dvofrk.

course, 10s.) from the General Secretary.

I had been a flautist

"--Koralle

(Berlin)

This content downloaded from 130.126.162.126 on Tue, 17 Feb 2015 23:44:40 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Representing Sound: Notes on the Ontology of Recorded Musical CommunicationsDa EverandRepresenting Sound: Notes on the Ontology of Recorded Musical CommunicationsNessuna valutazione finora

- An Introduction To Organ MusicDocumento18 pagineAn Introduction To Organ Musicdolcy lawounNessuna valutazione finora

- After-Thoughts (Tristan Murail)Documento4 pagineAfter-Thoughts (Tristan Murail)Jose ArchboldNessuna valutazione finora

- Journal of Borderland Research - Vol XLVII, No 5, September-October 1991Documento32 pagineJournal of Borderland Research - Vol XLVII, No 5, September-October 1991Thomas Joseph Brown100% (1)

- Colour-Music: The Art of Mobile Colour: Prefatory Notes by Hubert von Herkomer and W. BrownDa EverandColour-Music: The Art of Mobile Colour: Prefatory Notes by Hubert von Herkomer and W. BrownNessuna valutazione finora

- Singing or Music: A Suggestion Author(s) : Constantin Von Sternberg Source: The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 3, No. 2 (Apr., 1917), Pp. 243-248 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 15/05/2014 01:07Documento7 pagineSinging or Music: A Suggestion Author(s) : Constantin Von Sternberg Source: The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 3, No. 2 (Apr., 1917), Pp. 243-248 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 15/05/2014 01:07Ana CicadaNessuna valutazione finora

- Violins and Violin Makers: Biographical Dictionary of the Great Italian Artistes, their Followers and Imitators, to the present time. With Essays on Important Subjects Connected with the ViolinDa EverandViolins and Violin Makers: Biographical Dictionary of the Great Italian Artistes, their Followers and Imitators, to the present time. With Essays on Important Subjects Connected with the ViolinNessuna valutazione finora

- Singing PolyphonyDocumento13 pagineSinging Polyphonyenderman salami100% (1)

- Infinite Music: Imagining the Next Millennium of Human Music-MakingDa EverandInfinite Music: Imagining the Next Millennium of Human Music-MakingNessuna valutazione finora

- Taruskin 82 - On Letting The Music Speak For Itself Some Reflections On Musicology and PerformanceDocumento13 pagineTaruskin 82 - On Letting The Music Speak For Itself Some Reflections On Musicology and PerformanceRodrigo BalaguerNessuna valutazione finora

- Stockfelt AdequateModesOfListening AudioCultureDocumento4 pagineStockfelt AdequateModesOfListening AudioCultureAlexandre Trajano PequiniNessuna valutazione finora

- Vocal Ornaments in VerdiDocumento53 pagineVocal Ornaments in VerdiMcKocour100% (4)

- Past Sounds: An Introduction to the Sonata Idea in the Piano TrioDa EverandPast Sounds: An Introduction to the Sonata Idea in the Piano TrioNessuna valutazione finora

- Hot Topic Canonetta ArticleDocumento3 pagineHot Topic Canonetta ArticleMichael NorrisNessuna valutazione finora

- Violins and Violin Makers Biographical Dictionary of the Great Italian Artistes, their Followers and Imitators, to the present time. With Essays on Important Subjects Connected with the Violin.Da EverandViolins and Violin Makers Biographical Dictionary of the Great Italian Artistes, their Followers and Imitators, to the present time. With Essays on Important Subjects Connected with the Violin.Nessuna valutazione finora

- The University of Chicago Press Critical InquiryDocumento20 pagineThe University of Chicago Press Critical InquiryAna Alfonsina MoraNessuna valutazione finora

- Daniel Leech-Wilkinson - Early Recorded Violin Playing: Evidence For What?Documento19 pagineDaniel Leech-Wilkinson - Early Recorded Violin Playing: Evidence For What?lemon-kunNessuna valutazione finora

- Musical Instrument Design: Practical Information for Instrument MakingDa EverandMusical Instrument Design: Practical Information for Instrument MakingValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (9)

- The Changing Sound of MusicDocumento234 pagineThe Changing Sound of MusicJorge Lima Santos100% (1)

- 10 Musical InstrumentsDocumento326 pagine10 Musical InstrumentsglassyglassNessuna valutazione finora

- Peter Greenhill: Discussions On The Music of The Robert Ap Huw ManuscriptDocumento211 paginePeter Greenhill: Discussions On The Music of The Robert Ap Huw Manuscriptpeter-597928100% (4)

- Ihde Technologies Musics EmbodimentsDocumento18 pagineIhde Technologies Musics EmbodimentsdssviolaNessuna valutazione finora

- Lunn HistoryMusicalNotation 1866Documento4 pagineLunn HistoryMusicalNotation 1866kennyyjlimNessuna valutazione finora

- Opera DissertationDocumento6 pagineOpera DissertationPaperWriterServicesSingapore100% (1)

- The Performers Place in The Process and Product of RecordingDocumento17 pagineThe Performers Place in The Process and Product of RecordingOmar SorianoNessuna valutazione finora

- Fisk - New SimplicityDocumento20 pagineFisk - New Simplicityeugenioamorim100% (1)

- Smart Concerts: Orchestras in The Age of EdutainmentDocumento20 pagineSmart Concerts: Orchestras in The Age of EdutainmentSergioAntónMelgarejo100% (1)

- Linking Soundscape Composition and Acoustic EcologyDocumento14 pagineLinking Soundscape Composition and Acoustic EcologyΜέμνων ΜπερδεμένοςNessuna valutazione finora

- Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Royal Musical AssociationDocumento31 pagineTaylor & Francis, Ltd. Royal Musical AssociationKris4565krisNessuna valutazione finora

- On Transcribing African MusicDocumento5 pagineOn Transcribing African Musicmarcus motaNessuna valutazione finora

- Hector BerliozDocumento6 pagineHector BerliozthiboneNessuna valutazione finora

- Scoring For VoiceDocumento82 pagineScoring For VoiceHeber Peredo80% (5)

- Der Vollkommene CapellMeister Book IIDocumento220 pagineDer Vollkommene CapellMeister Book IIAntonio G100% (8)

- Authenticity in Contemporary MusicDocumento8 pagineAuthenticity in Contemporary Musicwanderingted100% (1)

- Historical Instruments and Their RoleDocumento9 pagineHistorical Instruments and Their Rolestudioguida.bs8611Nessuna valutazione finora

- Blacking - J - How Musical Is ManDocumento36 pagineBlacking - J - How Musical Is ManCheyorium Complicatorum100% (2)

- Last Night A DJ Saved My Life: Dance Music, Space, and Ritual Experience.Documento44 pagineLast Night A DJ Saved My Life: Dance Music, Space, and Ritual Experience.Peter KaufmannNessuna valutazione finora

- III - Musical IssuesDocumento29 pagineIII - Musical IssuesMadalina HotoranNessuna valutazione finora

- Chironomy PDFDocumento101 pagineChironomy PDFsupermaqp100% (1)

- Brian Ferneyhough - Jonathan Harvey PDFDocumento7 pagineBrian Ferneyhough - Jonathan Harvey PDFAurelio Silva Sáez100% (2)

- Philip, Robert - Studying Recordings-The Evolution of A DisciplineDocumento11 paginePhilip, Robert - Studying Recordings-The Evolution of A DisciplineNoMoPoMo576Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Pros of Historical PerformanceDocumento1 paginaThe Pros of Historical PerformanceJeanette Hiu Ying SzetoNessuna valutazione finora

- Saving Our Nation's Choirs & ChorusesDocumento3 pagineSaving Our Nation's Choirs & ChorusesAndrés García AlbaridoNessuna valutazione finora

- Taruskin - On Letting The The Music SpeakDocumento13 pagineTaruskin - On Letting The The Music SpeakDimitris ChrisanthakopoulosNessuna valutazione finora

- An Interview With Karlheinz enDocumento18 pagineAn Interview With Karlheinz enplbrook100% (1)

- American Music Survey Final Exam PaperDocumento11 pagineAmerican Music Survey Final Exam Paperapi-609434428Nessuna valutazione finora

- Butt 4Documento15 pagineButt 4Scott DonianNessuna valutazione finora

- Cortot's Berceuse, Daniel Leech-WilkinsonDocumento29 pagineCortot's Berceuse, Daniel Leech-WilkinsonsophieallisonjNessuna valutazione finora

- SER47 - Robert Garfias Music PDFDocumento262 pagineSER47 - Robert Garfias Music PDFGeorgiana Gattina100% (1)

- Libin - Laurence - "Musical Instrument"Documento4 pagineLibin - Laurence - "Musical Instrument"Sam CrawfordNessuna valutazione finora

- Heber Pérez - Speaking: Circle 1Documento4 pagineHeber Pérez - Speaking: Circle 1Heber MishkinNessuna valutazione finora

- Historicalanthol01davirich PDFDocumento278 pagineHistoricalanthol01davirich PDFAntonio Celso Ribeiro100% (1)

- Eng Essay2 MusicDocumento7 pagineEng Essay2 Musicapi-654886415Nessuna valutazione finora

- Music of Environment Murray SchaefferDocumento55 pagineMusic of Environment Murray Schaefferataandrada123Nessuna valutazione finora

- Globokar - Future of MusicDocumento13 pagineGlobokar - Future of MusicAaron SmithNessuna valutazione finora

- Jazziz - Earl KlughDocumento54 pagineJazziz - Earl KlughJay Steele38% (21)

- Polymodality, Counterpoint, and Heptatonic Synthetic Scales in Jazz CompositionDocumento198 paginePolymodality, Counterpoint, and Heptatonic Synthetic Scales in Jazz Compositionr-c-a-d100% (1)

- Being: Marc CaryDocumento50 pagineBeing: Marc Caryr-c-a-dNessuna valutazione finora

- Advanced Modal Jazz Harmony Applied To Twentieth Century Music Compositional Techniques in Jazz StyleDocumento199 pagineAdvanced Modal Jazz Harmony Applied To Twentieth Century Music Compositional Techniques in Jazz Styler-c-a-d100% (1)

- Experiment: Robert Glasper'sDocumento54 pagineExperiment: Robert Glasper'sr-c-a-dNessuna valutazione finora

- Heptatonic Synthetic Scales Nomenclature and Their Teaching in Jazz TheoryDocumento20 pagineHeptatonic Synthetic Scales Nomenclature and Their Teaching in Jazz Theoryr-c-a-d100% (1)

- Patricia Barber: A Breed ApartDocumento44 paginePatricia Barber: A Breed Apartr-c-a-dNessuna valutazione finora

- Dukerenewed: JULY 2013 Digital EditionDocumento56 pagineDukerenewed: JULY 2013 Digital Editionr-c-a-d100% (1)

- 2013 PDFDocumento132 pagine2013 PDFr-c-a-d100% (1)

- Pure Poetry: Maria Schneider'sDocumento58 paginePure Poetry: Maria Schneider'sr-c-a-d100% (1)

- Medeski Flies Solo: MAY 2013 Digital EditionDocumento56 pagineMedeski Flies Solo: MAY 2013 Digital Editionr-c-a-dNessuna valutazione finora

- Ira Gitler's: Indie Artist CelebrationDocumento52 pagineIra Gitler's: Indie Artist Celebrationr-c-a-dNessuna valutazione finora

- Nothing But 'Nett: August 2013 Digital EditionDocumento58 pagineNothing But 'Nett: August 2013 Digital Editionr-c-a-dNessuna valutazione finora

- Road Royalty: Diana Krall'sDocumento132 pagineRoad Royalty: Diana Krall'sr-c-a-d100% (1)

- Jazz & Culture Vol. 2, 2019 PDFDocumento140 pagineJazz & Culture Vol. 2, 2019 PDFr-c-a-dNessuna valutazione finora

- Music Group Assessment RubricDocumento1 paginaMusic Group Assessment Rubricr-c-a-dNessuna valutazione finora

- Editorial: Roger Fagge and Nicholas GebhardtDocumento278 pagineEditorial: Roger Fagge and Nicholas Gebhardtr-c-a-dNessuna valutazione finora

- Vol 12Documento158 pagineVol 12r-c-a-dNessuna valutazione finora

- Editorial: Catherine Tackley and Tony WhytonDocumento7 pagineEditorial: Catherine Tackley and Tony Whytonr-c-a-dNessuna valutazione finora

- Jazz & Culture Vol. 2, 2019 PDFDocumento140 pagineJazz & Culture Vol. 2, 2019 PDFr-c-a-dNessuna valutazione finora

- JINY May10 webFINAL R2 PDFDocumento84 pagineJINY May10 webFINAL R2 PDFr-c-a-dNessuna valutazione finora

- JINY Nov10 webFINAL PDFDocumento68 pagineJINY Nov10 webFINAL PDFr-c-a-dNessuna valutazione finora

- Jazz Research PDFDocumento97 pagineJazz Research PDFr-c-a-dNessuna valutazione finora

- Jazz & Culture Vol. 1, 2018 PDFDocumento149 pagineJazz & Culture Vol. 1, 2018 PDFr-c-a-dNessuna valutazione finora

- JINYJune14webFINAL PDFDocumento80 pagineJINYJune14webFINAL PDFr-c-a-d100% (1)

- September Issue of Jazz Inside NY MagazineDocumento84 pagineSeptember Issue of Jazz Inside NY MagazinetracylockettNessuna valutazione finora

- BanacosDocumento102 pagineBanacosArtem Mahov100% (21)

- Natalie Wren CornwallDocumento8 pagineNatalie Wren Cornwallr-c-a-dNessuna valutazione finora

- Alexander Rosenblatts Piano Sonata No2 and Its Influences The Blending of Classical Techniques and Jazz ElementsDocumento85 pagineAlexander Rosenblatts Piano Sonata No2 and Its Influences The Blending of Classical Techniques and Jazz Elementsr-c-a-dNessuna valutazione finora

- Gmail - Re - Postpaid Sim ReactiveDocumento2 pagineGmail - Re - Postpaid Sim ReactiveDIMPLE KUMARINessuna valutazione finora

- Unit-2 - Lessons-1 - 2 - 6th - Level 2Documento10 pagineUnit-2 - Lessons-1 - 2 - 6th - Level 2Jimmy AdrianoNessuna valutazione finora

- Lastexception 63796706523Documento20 pagineLastexception 63796706523Letícia NorbertoNessuna valutazione finora

- Philippine AirlinesDocumento3 paginePhilippine AirlinesDyann GarciaNessuna valutazione finora

- Electric EquipmentDocumento221 pagineElectric EquipmentCarlos Andrés Sánchez Vargas100% (1)

- QMLDocumento410 pagineQMLMani Rathinam RajamaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Health and Physical Education AssignmentDocumento7 pagineHealth and Physical Education AssignmentblahNessuna valutazione finora

- Wellness Activity PlanDocumento6 pagineWellness Activity PlanjizzaNessuna valutazione finora

- Itera Lec Reviewer-PrelimDocumento26 pagineItera Lec Reviewer-PrelimMark SimeonNessuna valutazione finora

- Openings ListDocumento48 pagineOpenings ListJhonny CehNessuna valutazione finora

- Battle Hymn Chorale - Full ScoreDocumento2 pagineBattle Hymn Chorale - Full ScoreAnderson MichelNessuna valutazione finora

- Gucci Group in 2009Documento8 pagineGucci Group in 2009Ayush MishraNessuna valutazione finora

- Don Featherstone Colonial RulesDocumento2 pagineDon Featherstone Colonial RulesA Jeff ButlerNessuna valutazione finora

- Dressing For SuccessDocumento18 pagineDressing For SuccessGandhi SagarNessuna valutazione finora

- Hedwig OwlDocumento5 pagineHedwig Owlanetamajkut173Nessuna valutazione finora

- Grooving With The Clave: GuitarDocumento4 pagineGrooving With The Clave: GuitarJosmer De Abreu100% (1)

- Marvel EncyclopediaDocumento7 pagineMarvel EncyclopediaKris Guillermo25% (4)

- Test Paper Clasa A IV-aDocumento2 pagineTest Paper Clasa A IV-aCrina MiklosNessuna valutazione finora

- B.P.R.D. Field Manual RevisedDocumento98 pagineB.P.R.D. Field Manual RevisedLord Hill75% (4)

- Tauplitz Bergfalter 2012-13 GB-WWWDocumento2 pagineTauplitz Bergfalter 2012-13 GB-WWWbcnv01Nessuna valutazione finora

- Hooded Scarf: Knitting For WomenDocumento3 pagineHooded Scarf: Knitting For WomenRowan CotaNessuna valutazione finora

- 4CC Carrier Aggregation - AlexDocumento19 pagine4CC Carrier Aggregation - Alexel yousfiNessuna valutazione finora

- Imanuel Danang Social ReportDocumento17 pagineImanuel Danang Social ReporteddoNessuna valutazione finora

- Gaminator 5 in 1Documento17 pagineGaminator 5 in 1Jose El Pepe Arias0% (1)

- Starcade Sidepanel PDFDocumento7 pagineStarcade Sidepanel PDFJesusMoyaLopezNessuna valutazione finora

- Blueprint of CCDDocumento1 paginaBlueprint of CCDShri PanchavisheNessuna valutazione finora

- Kaup 2015Documento128 pagineKaup 2015crash2804Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cultural ResonanceDocumento15 pagineCultural ResonanceAdithya NarayanNessuna valutazione finora

- Asp Et Opacification Digestive Tim 2Documento56 pagineAsp Et Opacification Digestive Tim 2Micuss La Merveille BoNessuna valutazione finora

- MpegDocumento38 pagineMpegVinayKumarSinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Bare Bones: I'm Not Lonely If You're Reading This BookDa EverandBare Bones: I'm Not Lonely If You're Reading This BookValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (11)

- The Storyteller: Expanded: ...Because There's More to the StoryDa EverandThe Storyteller: Expanded: ...Because There's More to the StoryValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (13)

- Twilight of the Gods: A Journey to the End of Classic RockDa EverandTwilight of the Gods: A Journey to the End of Classic RockValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (28)

- Altamont: The Rolling Stones, the Hells Angels, and the Inside Story of Rock's Darkest DayDa EverandAltamont: The Rolling Stones, the Hells Angels, and the Inside Story of Rock's Darkest DayValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (25)

- The Voice: Listening for God’s Voice and Finding Your OwnDa EverandThe Voice: Listening for God’s Voice and Finding Your OwnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (3)

- The Grand Inquisitor's Manual: A History of Terror in the Name of GodDa EverandThe Grand Inquisitor's Manual: A History of Terror in the Name of GodNessuna valutazione finora

- You Never Give Me Your Money: The Beatles After the BreakupDa EverandYou Never Give Me Your Money: The Beatles After the BreakupNessuna valutazione finora

- The Best Strangers in the World: Stories from a Life Spent ListeningDa EverandThe Best Strangers in the World: Stories from a Life Spent ListeningValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (31)

- They Can't Kill Us Until They Kill UsDa EverandThey Can't Kill Us Until They Kill UsValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (38)

- The Voice: Listening for God's Voice and Finding Your OwnDa EverandThe Voice: Listening for God's Voice and Finding Your OwnValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1)

- Remembering Whitney: My Story of Life, Loss, and the Night the Music StoppedDa EverandRemembering Whitney: My Story of Life, Loss, and the Night the Music StoppedValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (14)

- They Call Me Supermensch: A Backstage Pass to the Amazing Worlds of Film, Food, and Rock 'n' RollDa EverandThey Call Me Supermensch: A Backstage Pass to the Amazing Worlds of Film, Food, and Rock 'n' RollValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (8)

- Dylan Goes Electric!: Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night that Split the SixtiesDa EverandDylan Goes Electric!: Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night that Split the SixtiesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (23)

- The Man Who Sold the World: David Bowie and the 1970sDa EverandThe Man Who Sold the World: David Bowie and the 1970sNessuna valutazione finora

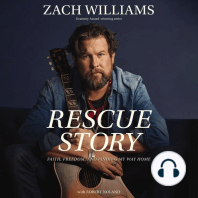

- Rescue Story: Faith, Freedom, and Finding My Way HomeDa EverandRescue Story: Faith, Freedom, and Finding My Way HomeValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (5)