Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

A Bullying Intervention System in High School A Two-Year School-Wide Follow-Up

Caricato da

LorenzoTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

A Bullying Intervention System in High School A Two-Year School-Wide Follow-Up

Caricato da

LorenzoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Studies in Educational Evaluation 36 (2010) 8392

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Studies in Educational Evaluation

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/stueduc

A bullying intervention system in high school: A two-year school-wide follow-up

Kathleen P. Allen *

University of Rochester, Margaret Warner Graduate School of Education and Human Development, Box 270425, Rochester, NY 14627-0425, United States

A R T I C L E I N F O

A B S T R A C T

Article history:

Received 15 March 2010

Received in revised form 21 October 2010

Accepted 25 January 2011

This study is an evaluation of a systemic, two-year, whole-school bullying intervention initiative that

was implemented in a US public high school. Students and staff members were anonymously surveyed

before and after the intervention. The goals of the initiative were to reduce bullying and victimization,

increase disclosure, increase intervention efforts, and reduce student aggression. Except for a reduction

in victimization, all goals were achieved in some measure. Self-reported bullying decreased 50% or more.

Students reporting that peers intervened in bullying increased. Staff-reported reductions in student

aggression, and staffs belief that the schools efforts to address bullying were adequate increased. This

evaluation points to the possible success of a whole-school, systemic approach to managing bullying at

the high school level.

2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords:

Program evaluation

Bullying

Victimization

Bullying in high school

Bullying among adolescents

Introduction

Statement of the problem

Bullying in schools is a problem which thrust itself onto the

national stage in the United States in the late 1990s, primarily

because of the attention given to the fact that bullying was

implicated in the Columbine shootings (Vossekuil, Fein, Reddy,

Borum, & Modzeleski, 2002). While this event took place in a high

school context, suggesting that bullying was a problem for

adolescents, most research on bullying in schools has focused

on elementary and middle school children with the one major US

survey on the problem excluding students in eleventh and twelfth

grades (Nansel et al., 2001). A review of research on bullying, which

to a large extent reects work done outside of the US, indicates that

studies of bullying seldom go beyond subjects aged 14 (Atlas &

Pepler, 1998; Boulton & Smith, 1994; Craig & Pepler, 1997;

Kaukiainen et al., 2002; OConnell, Pepler, & Craig, 1999; Olweus,

1978; Salmivalli & Kaukiainen, 2004; Salmivalli & Nieminen, 2002;

Sutton, Smith, & Swettenham, 1999), and with a rare exception,

consider students up to age 16 (Olweus, 1991; Rigby & Slee, 1991;

Whitney & Smith, 1993).

Perhaps because research on bullying tends to focus on

elementary aged children (Yoon, Barton, & Taiariol, 2004), interventions generally exclude high school students. A review of three

* Correspondence address: 58 Nobleman Court, Fairport, NY 14450, United

States. Tel.: +1 585 509 4893.

E-mail address: katyallen@rochester.rr.com.

0191-491X/$ see front matter 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.stueduc.2011.01.002

syntheses of bullying prevention/intervention evaluations suggests

that elementary and middle schools are more often the target of

these programs than are high schools (Baldry & Farrington, 2007;

Smith, Schneider, Smith, & Ananiadou, 2004; Vreeman & Carroll,

2007). Smith et al. (2004) reviewed 14 programs, only two of which

targeted students older than 16 years of age. In a review of 16

evaluations of bullying prevention programs by Baldry and

Farrington (2007), only two included students older than 16 years

of age, and in another review of school-based bullying interventions,

Vreeman and Carroll (2007) included 10 program evaluations, none

of which were implemented in a high school setting. In addition to

fewer interventions with older students, researchers have found

that the effectiveness of the programs targeting older children tends

to be less successful than those targeting younger children (Smith,

Ananiadou, & Cowie, 2003; Smith et al., 2004; Smith, 2010),

indicating the need for more and better interventions for older

children. In fact, Tto, Farrington, and Baldry (2008) recommend

that anti-bullying programs might well target children 11 years of

age or older, as opposed to younger students.

While research and interventions tend to be limited to children

and young adolescents, some studies have begun to describe the

psychosocial problems that adolescent victims of bullying may

experience. In a review of 37 studies that examined the association

between bullying and suicide, Kim and Leventhal (2008) concluded

that not only does bullying interfere with normal development

and educational processes but also places adolescents at an

unnecessary and additional risk for suicidal thoughts and actions

(p. 151). This trend was conrmed in a study by Klomek, Marrocco,

Kleinman, Schonfeld, and Gould (2007) with high school students

in New York State who concluded that frequent exposure to

K.P. Allen / Studies in Educational Evaluation 36 (2010) 8392

84

victimization or bullying others was related to high risks of

depression, ideation, and suicide attempts compared with adolescents not involved in bullying behavior. Infrequent involvement in

bullying behavior also was related to increased risk of depression

and suicidality, particularly among girls (p. 40). Finally, in a review

of psychiatric conditions associated with bullying among seventh

through twelfth graders, Kumpulainen (2008) suggests that bullying

is so troubling that it should be viewed as an experience that points

to the need for psychiatric evaluation.

Additionally, other researchers have suggested that bullying in

adolescence is related to other forms of aggression including

dating violence, romantic relational aggression, sexual harassment, and workplace harassment (Chapell, Hasselman, Kitchin,

Lomon, MacIver, & Sarullo, 2006; Connolly, Pepler, Craig, &

Taradash, 2000; Gruber & Fineran, 2008; Linder, Crick, & Collins,

2002; Pepler, Craig, Jiang, & Connolly, 2008; Porhola, Karhunen, &

Rainivaara, 2006). Thus, while prevalence rates for bullying and

victimization appear to go down as students get older (Madsen,

1996; Monks & Smith, 2006; Olweus, 1993; Smith, Madsen, &

Moody, 1999) bullying continues to be a problem for some

students as they move through high school and beyond, and is thus

worthy of attention and intervention.

Literature review

A review of meta-analyses of school-based bullying preventionintervention evaluations indicates that there is disagreement

among researchers as to the effectiveness of these types of

programs. Tto et al. (2008) indicate that overall, school programs

designed to reduce bullying and victimization are generally

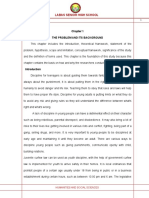

[()TD$FIG]

effective. Another meta-analysis (Merrell, Gueldner, Ross, & Isava,

2008) draws the conclusion that the majority of outcomes

evidenced no meaningful change, positive or negative. . . school

bullying interventions may produce modest positive outcomes. . .

they are more likely to inuence knowledge, attitudes, and selfperceptions rather than actual bullying behaviors (p. 26).

Vreeman and Carroll (2007) found that there was mixed success

when they reviewed 26 programs that were designed to reduce

bullying and victimization. Some resulted in reductions, but others

did not. Likewise, Smith et al. (2004) found that a small number of

programs yielded positive outcomes with the majority not

showing statistically signicant changes. In a recent article, several

leading bullying researchers concluded that these mixed results

suggest that, although school-based and schoolwide bullying

efforts can (italics in the original) be effective, success in one school

or context is no guarantee of success in another (Swearer,

Espelage, Vaillancourt, & Hymel, 2010).

While evaluation research has not sent clear signals with

regards to the effectiveness of preventionintervention programming in general, the research is fairly clear in indicating that

programs that have at least marginal success, generally adopt a

whole-school approach (Tto et al., 2008; Vreeman & Carroll,

2007). These programs are patterned after the Olweus Bullying

Prevention Program (Olweus, 1993) and include most or all of the

following features: a coordinating committee to oversee the

initiative; surveys to assess needs and measure change; well

disseminated policies and clear rules prohibiting bullying;

education that promotes awareness for parents, staff and students;

and individual support for victims and consequences for bullies.

These activities reect the multi-leveled nature of the intervention

ACTIVITIES

INPUTS

People: Building Planning

Team, SEL* Committee,

Teachers, Support Staff,

Administrators, Parents,

Students

Time

Monetary funds for surveys,

training, group meetings outside

of the school day, consultant

services, and evaluation

activities

Results of the April, 2005

Olweus Survey

Staff Responses to Olweus

Survey Data, Spring, 2006

Charge from the Building

Planning Team to address the

issue of bullying

Support from district level

administrators to design,

implement and evaluate a

bullying preventionintervention initiative

Two, four hour summer workshops

(2006) to explore issues and develop

recommendations for the Building

Planning Team

SEL* Committee meetings, held

monthly throughout the school year

SELiT meetings, held 1-2 times per

month as needed

SEL Committee members study, read,

and explore research on whole-school

bullying intervention efforts

SEL Committee planning for

professional development activities

with MPA staff for 2006-2007-2008

SEL Committee getting and processing

feedback from staff regarding initiative

progress

Development of a system to respond to

bullying

Ongoing professional development for

staff to support their use of the system

Programming for students on the Social

Support System, including a student

prepared video on bullying, assemblies

led by an educational expert on school

bullying, class discussions of the

assemblies, student orientation to the

Social Support System, and a parent

information night on the Social Support

System.

PROXIMAL

OUTCOMES

OUTPUTS

A Continuum of

Responses to

bullying for adult

intervention in

bullying situations

Students, staff and parents report

bullying situations.

Adults effectively intervene in, or

respond to, bullying situations.

A safe, bullying

reporting and

follow-up system

for students, staff

and parents

Heightened student

and staff awareness

of problems around

bullying and how to

access help to solve

these problems

Acceptance of

norms which

support respectful

peer treatment and

a rejection of

bullying as a form

of social interaction

INTERMEDIATE and

DISTAL

OUTCOMES

There is an overall reduction in the

amount and severity of bullying.

The quality of social interactions

among students improves.

The schools social climate becomes

more positive.

* Social-emotional Learning

Social-emotional Learning Intervention Team

Fig. 1. Logic model Meliora Public Academy bullying preventionintervention initiative.

K.P. Allen / Studies in Educational Evaluation 36 (2010) 8392

in that they address problems at the individual, class, school, and

community levels (Rahey & Craig, 2002; Tto et al., 2008).

Theoretical framework

Researchers who study bullying recommend that those who

seek to reduce bullying and aggression adopt a socialecological

perspective (Swearer & Espelage, 2004; Swearer et al., 2010).

Swearer and Espelage are of the view that bullying should be

considered across multiple contexts that include the individual,

family, peer, school and community. Drawing upon Bronfenbrenners ecological-systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), these

authors have proposed that bullying and victimization occur in

ecologies which are the result of complex inter- and intraindividual variables. They believe that effective prevention and

intervention efforts must take into consideration the social ecology

that promotes and maintains bullying behaviors. This perspective

is reected in the whole-school approach in that it seeks to alter

the context of bullying on multiple levels while addressing interand intra-individual concerns.

Goals of the current study

Following the framework of a whole-school approach to

resolving problems around bullying, the goals of this intervention

were to reduce bullying and victimization by bullying; increase

disclosure of bullying and victimization to adults; increase adult

and student interventions in bullying problems; reduce fear of

bullying; increase empathy for victims of bullying; reduce peer

aggression; increase staff knowledge of bullying and victimization;

and increase staff commitment to intervene in bullying and

victimization.

Program theory-driven evaluation

The evaluation of this initiative was designed using a theorydriven approach to evaluation (Chen & Rossi, 1983, 1992;

Donaldson, 2007; Donaldson & Gooler, 2003). Fig. 1 is a logic

model which describes the inputs, activities, outputs, and outcomes that made up the initiative and which were based on the

goals of the initiative. While the overall evaluation design resulted

in multiple evaluation questions, this report deals primarily with

questions concerning outcomes related specically to bullying and

victimization. An additional process evaluation is planned for

future publication.

Methods

Program description

Meliora Public Academy (a pseudonym), a public ninth through

twelfth grade high school, developed its bullying intervention

initiative after doing a needs assessment and organizing a

committee to oversee the initiative. The core component of the

initiative is the Social Support System (see Allen, 2009, 2010 for a

detailed description) and is comprised the following: (1) a bullying

reporting form which triggers the process; (2) a follow-up form

which documents the steps taken to resolve the problem; (3) an

intervention team which gathers information on problems,

coaches staff members who are dealing with bullying, and acts

as a clearing house for reports; and (4) a continuum of responses

for intervening in bullying which offers alternatives to the

traditional method of assigning blame and punishing bullies.

The Social Support System was considered the main feature of

the initiative because it addressed the most pressing question that

teachers ask: What am I supposed to do when I think bullying is

85

going on? Most bullying preventionintervention programs tend

to focus heavily on staff education that considers denitions,

prevalence, policy, and effects on victims and bystanders, while

giving little clear guidance on what to do and say when bullying is

occurring.

Because the staff was quite knowledgeable about bullying, the

committee felt that their most important work was to create a

continuum of responses to bullying problems that could be

implemented in a consistent way across the entire school. The

committee presented the Social Support System to the entire

faculty at the beginning of the 20072008 school year for piloting

during the rst semester, and then informed students of the

system after the start of the second semester.

The committee decided that the system should be presented to

the student body at a time when sensitivity to the issue of bullying

was high. Thus, the initiative rollout included: (1) the viewing of a

student-made video on bullying by all students on the rst day

back from February break; (2) followed the next day by interactive

assemblies for the student body where a nationally known speaker

discussed respect and bullying; (3) further discussion of the

assembly content during English classes over the next several

days; (4) the presentation of the Social Support System to students

by English teachers; and (5) a parent presentation on the Social

Support System three weeks after the student assemblies. This

initiative approximates a whole-school approach to addressing

bullying (Rahey & Craig, 2002), but does so in a way that considers

the structural features of a ninth through twelfth grade high school

and the developmental nature of adolescents aged 1418.

Design

This study is part of an evaluation which collected data before

and after the intervention. Students and staff members anonymously completed surveys before the implementation of the

initiative. Approximately two years later, during which time the

initiative was implemented, the surveys were administered again.

It was not possible to use repeated measures because there had

been a 50% change in the population of the school due to

graduation of eleventh and twelfth graders and the introduction of

two new classes of students. Likewise, turnover in staff precluded

the ability to survey an entirely identical set of staff members.

Thus, data from the surveys were not matched and participants

reected different groups pre- and post-assessment.

Participants

Participants for this study were the students and staff members

of Meliora Public Academy, a large suburban high school in the

Northeastern United States. Meliora Public Academy (MPA) is one

of two equal-sized high schools in a school district located in an

afuent community outside of a mid-sized city. The National

Center for Education Statistics (Ofce of Educational Research &

Improvements, 2010) indicates that the total student population of

MPA was 992 (485 males), 25 of whom were eligible for free or

reduced lunch (2.5%) for the 20072008 which was the rst year of

the intervention. The racial/ethnic prole for students as reported

by NCES (Ofce of Educational Research & Improvements, 2010)

for 20072008 was 5.4% Asian, 2.6% Black, 1.0% Hispanic, and 90.9%

White. Teachers totaled 79.1 and the student-to-teacher ratio was

12.5. The total student population of the entire school district for

20072008 was 6028 with 53 of those students being described as

English language learners.

Because repeated measures were not employed chi-square

tests of independence were performed to determine if the beforeintervention and after-intervention student samples differed

signicantly by gender or grade. Results indicated that there

86

K.P. Allen / Studies in Educational Evaluation 36 (2010) 8392

was no statistically signicant difference between the two groups

with regards to gender (x2(1) = 1.515, p = .218) or grade

(x2(1) = 1.28, p = .733). A chi-square was also performed to

determine if the staff members differed before- to after-intervention with regards to gender. The two groups were not found to

differ signicantly (x2(1) = .207, p = .649).

Bullying

Nine items from the student version of the Olweus Bully/Victim

Questionnaire (1996) were considered when determining if the

amount of bullying was different following the intervention as

compared to before. These questions mirrored the victimization

questions and thus the same methods for analysis were used to

measure bullying as were used to measure victimization.

Procedure

Students anonymously completed the Olweus Bully/Victim

Questionnaire (1996) in April, 2007. Two years later, students took

a survey that included questions from the Olweus Bully/Victim

Questionnaire and an additional set of questions that were

developed by the evaluator/author and piloted at a local high

school. The rst administration of the student survey yielded

approximately 870 completed surveys and the second yielded

approximately 820 surveys which represent 88% and 83% of the

student population respectively. The fact that less than 100% of the

students participated in the survey is due to absenteeism, parental

objection to student participation, incomplete surveys, or elimination of the surveys because the responses were grossly

inconsistent (e.g., student reports being a ninth grader and 19

years of age). Because the student body had changed by 50% due to

graduation and new enrollment of younger students, and due to

the inability to track surveys pre- to post-administration, this was

not a matched sample, and thus, repeated measures were not

possible.

Staff members anonymously completed a survey in January,

2007 which was designed by the evaluator/author and piloted by

the bullying initiative committee. Two years later staff members

took another survey which included all of the original questions

and an additional set of questions that mirrored the ones added to

the second student survey. The rst administration of the staff

survey yielded 120 completed surveys and the second yielded 78

surveys. This represents approximately 78% and 50% of the staff

population respectively. Again, this was not a matched sample due

to staff turnover and the inability to track surveys pre- to postadministration.

MPA followed district procedures for administering the student

surveys which were completed during homeroom periods under

the supervision of a teacher. Staff surveys were administered at

faculty or department meetings under the supervision of school

administrators or department leaders. All surveys were anonymous. The data were hand entered into SPSS v14 by district hires

and the program evaluator/author.

Measures

Victimization

Nine items from the student version of Olweus Bully/Victim

Questionnaire (1996) were considered when determining if the

amount of victimization by bullying was different following the

intervention as compared to before. If students indicated that they

had been bullied in any of the nine ways, they were considered to

have been victimized. The original questions were answered using

a 15 point Likert scale with 1 = It has not happened, and 5 = It

happens several times a week. In keeping with Solberg and

Olweus (2003) the variables for victimization were recoded into a

binary variable where 0 = It has not happened or it happened only

once or twice, and 1 = It has happened 23 times per month, once

a week or several times per week. Frequencies and percentage of

change for each item were calculated for the before- and afterintervention groups for the individual items. The nine original

items were combined into a composite variable and recoded into a

binary variable in keeping with Solberg and Olweus (2003) in order

to create a single measure of victimization.

Disclosing and reporting victimization

Four items from the student version of the Olweus Bully/Victim

Questionnaire (1996) elicited information on disclosing to adults

and reporting of victimization to the school. Students who had

been bullied indicated if they told a teacher, told another adult at

school, told a parent or guardian, and if someone from home had

contacted the school about the bullying. The data from the rst

three items were dichotomous and were answered with a yes or a

no. The data from the fourth item were ordinal and included the

following three responses: (1) No, they have not contacted the

school; (2) Yes, they have contacted the school; and (3) Yes,

they have contacted the school more than once.

Responding to bullying

Students were asked two questions from the Olweus Bully/

Victim Questionnaire (1996) regarding how others at school

respond to bullying. Regarding adults, students were asked: How

much do teachers do to counteract bullying? with possible

responses being on a 15 Likert scale with 1 = Little or nothing,

and 5 = Much. Regarding their peers, students were asked to

respond to the following statement: When students are aware of

bullying, they take action, with possible responses being a 15

Likert scale with 1 = Never or almost never, and 5 = Always or

almost always.

Fear of being bullied

Students were asked one question from the Olweus Bully/

Victim Questionnaire (1996) regarding fear of being bullied.

Students responded to the following question: How often are you

afraid of being bullied at school? with possible responses being a

16 Likert scale with 1 = Never, and 6 = Very often.1

Empathy

Students were asked three questions from the Olweus Bully/

Victim Questionnaire (1996) which measured empathy for victims of

bullying. The rst question: Do you think you could join in bullying a

student whom you dislike? was answered using a 16 Likert scale

with 1 = Yes, and 6 = Denitely, no (see footnote 1). Two other

questions addressed empathy for victims of bullying: When you see

a student your age being bullied at school, what do you feel or think?

and How do you usually react if you see or understand that a student

your age is being bullied by other students? Both variables were

recoded into binary variables which reected negative/neutral or

positive affect towards the victims of bullying.

Student aggression

Staff members were asked to consider a list of 16 aggressive

behaviors and to answer the following question on a 15 point

Likert scale with 1 = Not at all and 5 = Very often, with regard

to each behavior: How often do you feel the following behaviors

happen among students at our school or at school sponsored

activities? These 16 behaviors were: hitting, kicking, punching,

pushing, intimidation, stalking, sexual harassment, damaging

property, theft, taunting/ridicule, name calling, threats, hostile

gesturing, spreading lies, gossiping, and shunning.

1

It should be noted that this particular question on the Olweus Bully/Victim

Questionnaire had six possible responses, thus the 16 point Likert scale.

K.P. Allen / Studies in Educational Evaluation 36 (2010) 8392

87

Table 1

Percentages and percentage of change for self-reported student victimization and bullying, before and after the intervention.

. . . called mean names, made fun of, or teased in a hurtful way

. . . left out of things on purpose, excluded from groups of friends,

or completely ignored

. . . hit, kicked, pushed, and shoved around or locked indoors

. . . spread false rumors and tried to create dislike

. . . took money or other things or damaged belongings

. . . threatened or forced to do unwanted things

. . . mean names or comments made about race or color

. . . mean names, comments, or gestures made with a sexual meaning

. . . not mentioned previously

Victimization I was bullied in this

way. . .

Bullying I bullied in this way. . .

Pre survey

N = 874

Post survey

N = 817

Percentage

of change

Pre survey

N = 870

Post survey

N = 818

8.8%

5.9%

11.4%

6.7%

+29.5%

+13.7%

10.2%

7.1%

4.3%

3.5%

57.8%

50.7%

2.9%

7.2%

1.5%

3.1%

5.1%

5.3%

4.2%

3.4%

6.5%

1.5%

2.1%

5.1%

5.5%

2.8%

+17.2%

9.7%

0.0%

32.2%

.0%

+3.7%

33.3%

3.9%

3.9%

2.5%

2.8%

4.0%

3.8%

3.4%

1.7%

1.5%

.6%

1.1%

2.2%

2.1%

1.2%

56.4%

61.5%

76.0%

60.7%

45.0%

44.7%

64.7%

Knowledge, beliefs, and behaviors: staff perceptions

Staff members were asked eight questions regarding their

knowledge, beliefs, and behaviors with respect to bullying and

victimization within the school. These items were scored on a 15

Likert scale with 1 = Strongly disagree, and 5 = Strongly agree

(see Table 2 for a complete list of items).

Results

Victimization and bullying

Victimization

A calculation of frequencies comparing the before- and afterintervention groups for victimization indicated that some forms of

self-reported victimization increased and some decreased during

the time of the intervention (see Table 1). The Cronbach a for the

nine items was .900 so a composite variable was created and then

recoded to a binary variable. A chi-square test of independence was

performed to determine if there was a difference between the

before-intervention group and the after-intervention group. The

difference approached, but was not statistically signicant

(x2(1) = 2.83, p = .092) with a negligible effect size (.04),2 with

15.2% of students reporting victimization before the intervention

and 18.3% reporting victimization after. Although victimization

seems to have increased slightly the difference was not statistically

signicant, thus it can be concluded that self-reported victimization remained relatively stable during the time of the intervention.

Victimization by gender. A chi-square test of independence

comparing males before and after the intervention, and females

before and after the intervention was performed. The results

indicated that males reported more victimization after the

intervention (21.0% as compared to 15.9%) than before and that

the difference trended towards signicance (x2(1) = 2.40, p = .065).

There was no statistically signicant difference in self-reported

victimization for females after the intervention as compared to

before the intervention (p < .05).

Victimization by grade. Chi-square tests of independence comparing the before and after groups by grade level indicated a

statistically signicant increase in reporting of victimization for

ninth graders (x2(1) = 6.755, p = .009) with 26.0% reporting

victimization after as compared with 16.3% before. There were

no statistically signicant differences for tenth, eleventh or twelfth

2

Effect sizes for Cohens d (Cohen, 1988) used for chi-square test of

independence and independent samples t-test: r = .10 small, r = .30 medium,

r = .50 large.

Percentage of change

graders when comparing self-reports of victimization after the

intervention as compared to before the intervention (p < .05).

Bullying

The difference in bullying between the before- and afterintervention groups indicated that all forms of self-reported

bullying decreased during the time of the intervention by 4576%

(see Table 1). The Cronbach a for the nine items was .936 so a

composite variable was created and then recoded to a binary

variable. A chi-square test of independence was performed to

determine if there was a difference between the before-intervention group and the after-intervention group. Results showed a

statistically signicant difference between the before- and afterintervention groups (x2(1) = 17.75, p = .001) with 7.3% of students

reporting that they had bullied others after the intervention as

compared to 13.6% of students before, indicating that self-reported

bullying decreased during the time of the intervention although

the effect size was small (.10)2.

Bullying by gender and grade. A chi-square test of independence

comparing the before and after groups by gender indicated that the

trend of less self-reported bullying was found for both males and

females and was statistically signicant (p < .05). Chi-square tests

of independence comparing the before and after groups by grade

level also followed the same trend indicating less self-reported

bullying at each grade level. These differences were statistically

signicant for every grade (p < .05).

Disclosing victimization to adults and reporting victimization to the

school

Disclosure of victimization to adults was measured by three

items and reporting of victimization to the school by adults at

home was measured by a fourth item. Frequencies were calculated

and chi-square tests of independence were performed to determine statistical signicance for each item. In all cases there was an

increase in the percentages after the intervention when compared

with the before-intervention percentages. The percentage of

students saying they had told a teacher increased from 10.1% to

19.8%. This difference was statistically signicant (x2(1) = 3.98,

p = .046), but the effect size was small (.13)2, although it represents

a 51.0% percentage of change. The percentage of students telling

another adult at school increased from 21.2% to 23.2% which was

not statistically signicant (x2(1) = .120, p = .729). The percentage

of students reporting bullying to a parent or adult at home

increased from 40.3% to 45.1% but was not statistically signicant

(x2(1) = .49, p = .482). Parental notication of the school was

measured as contacting the school once, or contacting the school

more than once. Responses to these items increased following the

intervention, from 10.2% to 17.5% for the former and 4.8% to 8.8%

88

K.P. Allen / Studies in Educational Evaluation 36 (2010) 8392

for the later. These differences were not statistically signicant

(x2(2) = 3.87, p = .144) although they represent a 58.8% and 54.4%

percentage of change respectively. Students slightly increased their

reporting of victimization to all adults, but the increase in reporting

to teachers was the only difference that was statistically signicant.

Beforeafter differences by gender. Chi-square tests of independence

were conducted to determine if there were differences with regards to

gender when comparing the after-intervention group to the beforeintervention group. The only variable which showed statistically

signicant differences for males was having an adult at home report to

the school (x2(2) = 8.56, p = .014) with 37.5% having reported once or

more after the intervention as compared to 11.9% before the

intervention. None of the variables indicated a statistically signicant

difference when comparing the females in the after-intervention

group to the before-intervention group (p < .05).

Beforeafter differences by grade. Chi-square tests of independence

were conducted to determine if there were differences with

regards to grade level when comparing the after-intervention

group to the before-intervention group. Among the four variables

there were no statistically signicant differences when comparing

ninth, tenth and twelfth grade students after the intervention to

before the intervention (p < .05). However, for eleventh grade

students 30.0% of students told a teacher about being bullied after

the intervention as compared to 3.0% before the intervention and

the difference was statistically signicant (x2(1) = 7.90, p = .009).

Responding to bullying: student perceptions

Teacher intervention in bullying

An independent samples t-test was performed and effect sizes

were calculated to determine if there was a difference in how students

viewed teachers efforts to intervene in bullying before and after the

intervention. The mean score of students after the intervention

(m = 2.38, sd = 1.185) was greater than before the intervention

(m = 2.26, sd = 1.193 and the difference was statistically signicant

(t(1670) = 2.112, p = .035) with a small effect size of .102 indicating

that students perceived teachers to respond more to bullying

problems after the intervention than they did before the intervention.

Beforeafter differences by gender. An independent samples t-test

was done to see if there was a difference for gender when

comparing the after-intervention group with the before-intervention group. No statistically signicant differences (p < .05) were

found for males or for females.

Beforeafter differences by grade. An independent samples t-test

was done to see if there were differences with regards to grade

level when comparing the after-intervention group with the

before-intervention group. No statistically signicant differences

were found for ninth, eleventh or twelfth graders (p < .05).

However, there was a statistically signicant difference

(t(413) = 2.098, p = .037) for tenth graders with more students

reporting that teachers increased their efforts to counteract

bullying following the intervention (m = 2.43, sd = 1.236) as

compared to before the intervention (m = 2.18, sd = 1.169).

Student intervention in bullying

An independent samples t-test was performed and effect sizes

were calculated to determine if there was a difference in how

students viewed their peers responses to bullying when they were

aware of it before and after the intervention. The mean score of

students after the intervention (m = 2.74, sd = 1.059) was greater

than before the intervention (m = 2.21, sd = 1.004) and the

difference was statistically signicant (t(1673) = 10.523,

p = .001) and produced a large effect size of .512 indicating that

students perceived a large increase in their peers responses to

bullying problems after the intervention as compared with before

the intervention.

Beforeafter differences by gender and grade level. An independent

samples t-test was done to see if there was a difference for gender

when comparing the after-intervention group with the beforeintervention group. The differences for both males and females were

statistically signicant (p < .05), mirroring the pattern of ndings for

the aggregated data. Likewise, an independent samples t-test

comparing the after-intervention group to the before-intervention

group by grade levels followed the same pattern of results with the

differences being statistically signicant (p < .05) at all grade levels.

Fear of being bullied

Because the data on fear of being bullied at school were highly

skewed, a MannWhitney U-test was performed to determine if

the difference after the intervention was statistically signicant

when compared to before the intervention. Prior to the intervention, students were signicantly (m place = 866.97) more likely to

fear being bullied than students following the intervention (m

place = 822.7), (U = 337,978.00, p = .031). Thus, fear of being

bullied decreased following the intervention, but with a very

small effect size (.05)3 that was statistically signicant.

Beforeafter differences by gender. A MannWhitney U-test was

done to determine if there were differences before the intervention

as compared to after the intervention by gender. Males were more

afraid of being bullied before the intervention than after, but the

difference was not statistically signicant (p < .05). Females were

also more afraid of being bullied before the intervention than after,

and the difference was statistically signicant (p = < .05).

Beforeafter differences by grade. A MannWhitney U-test was

done to determine if there were differences before the intervention

as compared to after the intervention by grade level. Ninth, tenth

and twelfth graders were less afraid of being bullied following the

intervention than before the intervention and the difference

approached or was statistically signicant (p < .05). However,

eleventh graders were slightly more afraid of being bullied after

the intervention as compared to before the intervention, but the

difference was not statistically signicant (p < .05).

Empathy for bullied students

Bullying a disliked student

An independent samples t-test was done to see if the beforeintervention group differed from the after-intervention group with

regards whether or not a student could join in bullying a disliked

student. The mean of the before-intervention group was lower

(m = 3.67, sd = 1.67) than the mean of the after-intervention group

(m = 3.90, sd = 1.63) indicating an increase in prosocial feelings

towards students who are disliked. The difference after the

intervention as compared to before the intervention was statistically

signicant (t(1687) = 2.952, p = .003) and the effect size was small

(.14)3.

Beforeafter differences for gender. An independent samples t-test

was done to determine if there were differences by gender. Males

indicated that they were less likely to join in bullying a student

whom they disliked after the intervention (m = 3.42, sd = 1.697)

than before the intervention (m = 3.16, sd = 1.659), and the

3

Effect size ranges for MannWhitney U (Rosenthal, 1991): <.09 trivial, .12.3

small (minor), .24.36 moderate, .371.0 large.

K.P. Allen / Studies in Educational Evaluation 36 (2010) 8392

difference was statistically signicant (t(801) = -2.188, p = .029).

Females, on the other hand, who seemed to indicate both before

and after the intervention that they were not likely to bully a

student whom they disliked, were not different after the

intervention (m = 4.33, sd = 1.441) when compared with before

the intervention (m = 4.17, sd = 1.526) (t(869) = 1.603, p = .109),

although their mean scores before and after the intervention were

higher than males scores. This suggests that while females appear

to be more empathic than males overall, the intervention may have

had a particular effect on males and their empathic feelings for

victims, particularly with regards to bullying a disliked student.

Beforeafter differences for grade. An independent samples t-test

was done to determine if there were differences by grade level.

Ninth graders indicated that they were less likely to join in bullying

a student whom they disliked after the intervention than before

the intervention and the difference was statistically signicant

(p < .05). For the other three grade levels, students were less likely

to join in bullying a student whom they disliked after the

intervention, but the differences were not statistically signicant

(p < .05).

Thoughts and feelings towards victims

A chi-square test of independence was performed to determine

if thoughts and feelings about victims were different after the

intervention than before the intervention. Results indicated that

there was a statistically signicant difference (x2(1) = 27.86,

p = .001) and that the effect size was small (.13)2 with 56.2% of

students indicating empathy for victims after the intervention as

compared to 42.8% of students before the intervention.

Beforeafter differences for gender. A chi-square test of independence was performed to determine if thoughts and feelings about

victims were different after the intervention as compared to before

the intervention by gender. The difference for males was

statistically signicant (x2(1) = 6.573, p = .010) with 42.1% of

males feeling empathy for victims after the intervention as

compared to 32.9% before. The difference for females was also

statistically signicant (x2(1) = 21.505, p = .001) with 67.9% of

females feeling empathy for victims after the interventions as

compared to 52.0% before. Again, while females seem to be

generally more empathic than males, the results indicate that the

intervention may have had a particular effect on males with

regards to increasing their empathy for victims of bullying.

Beforeafter differences for grade. A chi-square test of independence was done to see if thoughts and feelings about victims were

different after the intervention as compared to before the

intervention by grade level. At all grade levels, the percentage of

89

students feeling empathy for victims increased. The differences

were statistically signicant for ninth and tenth graders, but not for

eleventh and twelfth graders (p < .05).

Reactions to observing victimization

A chi-square test of independence was performed to determine

if students reactions to observing bullying was different after the

intervention than before the intervention. Results indicated that

there was a statistically signicant difference (x2(1) = 9.85,

p = .002) and that the effect size was small (.08)3 with 87.2% of

students indicating empathy for victims after the intervention as

compared to 81.0% of students before the intervention.

Beforeafter differences for gender. A chi-square test of independence was performed to determine if reactions to observing

victimization were different after the intervention as compared to

before the intervention by gender. The difference for males was not

statistically signicant (x2(1) = 1.956, p = .162) with 42.1% of

males feeling empathy for victims after the intervention as

compared to 32.9% before. However, the difference for females

was statistically signicant (x2(1) = 8.820, p = .003) with 94.1% of

females feeling empathy for victims after the intervention as

compared to 87.7% before. As before, females more than males are

more likely to feel sympathy for victims of bullying, but in the case

of how they respond to observing victimization, females more than

males may have been affected by the intervention with regards to

this variable.

Beforeafter differences for grade. A chi-square test of independence was done to see if reactions to observing victimization were

different after the intervention as compared to before the

intervention by grade level. At all grade levels, the percentage of

students feeling empathy for victims increased. The differences

were statistically signicant for ninth and eleventh graders, but not

for tenth and twelfth graders (p < .05).

Student aggression: staff perceptions

Staff members considered 16 items that described aggressive

behaviors that students might engage in. Because the Cronbach a

for these 16 variables was .895, a composite variable was created.

An independent samples t-test indicated that there was a

statistically signicant difference (t(196) = 3.143, p = .002) in staff

perceptions of student aggression following the intervention. The

before-intervention mean of the composite variable was 2.55

(sd = .556) and the after-intervention mean of the composite

variable was 2.31 (sd = .495) with the effect size (.46)2 falling in the

moderate range, indicating that staff members saw a noteworthy

decrease in student aggression following the intervention as

compared to before the intervention.

Table 2

Staff percentages for pre- and post-survey responses strongly agree and agree, effect sizes and statistical signicance for knowledge, beliefs, and behaviors with regards to

bullying and victimization.

I am condent that I know what bullying is

I am familiar with the school policy on bullying in the handbook

I feel that our schools efforts to deal with bullying are adequate

I am condent in my ability to recognize bullying in school

I am condent in my ability to distinguish fun teasing from bullying

I am condent in my ability to distinguish normal conict

from bullying conict

I can condent in my ability to respond to bullying in school

When I am aware of bullying I take action to intervene

p < .05.

Pre-survey: strongly

agree + agree N = 120

Post-survey: strongly

agree + agree N = 78

Percentage

of change

Effect size

93.3%

81.7%

52.5%

85.8%

83.3%

85.8%

97.4%

91.1%

82.0%

91.0%

87.2%

91.0%

+4.3%

+11.5%

+56.1%

+6.0%

+4.6%

+6.0%

1.152

1.393

5.048*

1.295

1.606

1.956*

.10

.09

.35

.09

.11

.13

66.7%

86.7%

83.4%

94.8%

+25.0%

+13.4%

2.719*

2.081*

.19

.14

90

K.P. Allen / Studies in Educational Evaluation 36 (2010) 8392

Knowledge, beliefs, and behaviors: staff perceptions

Eight items assessed staff members knowledge, beliefs and

behaviors with regards to bullying using a 15 Likert scale.

Responses for strongly agree and agree were combined and

percentage of change was calculated (see Table 2). Frequencies

indicated increases in knowledge about bullying, stronger antibullying beliefs, and greater ability and willingness to respond to

bullying behaviors after the intervention as compared to before the

intervention. The MannWhitney U-test was performed on each

variable to determine statistical signicance and to calculate effect

size (see Table 2).

Four of the items were statistically signicant and had minor to

moderate effect sizes. It appears that staff are quite condent in

their abilities to recognize and intervene in bullying as evidenced

by the high percentages of strongly agree plus agree on these

items in the follow-up survey. Staff members also showed small

but statistically signicant differences following the intervention

as compared to before the intervention in their abilities to

recognize and intervene in bullying problems. In particular it is

noteworthy that there was a statistically moderate difference

following the intervention in staff members feelings regarding the

adequacy of the schools response to bullying problems.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to assess the differences that may

have occurred as a result of a bullying intervention initiative at a

high school. In particular the study considered differences

following the intervention as compared to before the intervention

in amounts of bullying and victimization, student and family

disclosure or reporting of bullying, adult and student responses to

bullying, fear of being bullied at school, empathy for victims, staff

perceptions of student aggression, and staff members knowledge,

beliefs and behaviors with regards to bullying. Except for

victimization, which remained relatively stable, the differences

after the intervention as compared to before the intervention

indicate that self-reported bullying decreased, disclosure of

victimization increased, fear of bullying decreased, empathy for

victims increased, student aggression decreased, and staff increased knowledge, positively altered their beliefs, and positively

altered their behaviors with regards to responding to bullying.

Because the data did not reect a matched sample, it is difcult

to know if the self-reported stability of victimization is due to no

differences in victimization or if it is due to differences with

regards to awareness of bullying and victimization. It is possible

that the effect of the intervention was to cause some students who

had not viewed themselves as victims to realize that they had been

victimized and to report it on the post-survey when they might not

have reported it on the pre-survey. Likewise, some students who

thought themselves to be victims might have concluded as a result

of the intervention that they were not victims, although they had

reported that they were on the pre-survey. While differences of

this sort might result in a net effect that points to stabilized

victimization, it is feasible that there might have been an increase

or a decrease in victimization that is not accounted for in the data.

While it is discouraging that reductions in victimization by

bullying were not observed, it is quite encouraging that all forms of

self-reported bullying decreased in rather substantial amounts,

particularly when the percentage of decrease is considered.

Although this seems somewhat contradictory that victimization

might not change when bullying is reported to have decreased, it is

not uncommon to achieve ndings of this sort in bullying research,

particularly when victimization and bullying are measured

separately (Frey, Hirschstein, Snell, Edstrom, MacKenzie &

Broderick, 2005; Leadbeater, Hoglund, & Woods, 2003; Orpinas,

Horne, & Staniszeski, 2003; Pepler, Craig, Ziegler, & Charach, 1994).

The signicant reduction in self-reported bullying may have

occurred because of the heightened awareness that resulted from

the intervention and the recognition of students that their

previously reported behaviors were unacceptable. This new

awareness might have resulted in underreporting of behaviors

as opposed to an actual reduction in bullying in the post-survey. On

the other hand, the self-reported reduction in bullying may have

been due to the fact that a number of students who had previously

engaged in bullying realized that their behaviors were hurtful and

stopped these behaviors. Regardless, it seems that the ndings on

bullying and victimization suggest that there is perhaps a small

amount of chronic victimization which may be being perpetrated

by a small, rather intransigent group of bullies, and that the

intervention did not alter these dynamics to any large extent. If this

is the case, then the intervention may have had the greatest impact

on students who engage in milder forms of bullying or who support

the aggression of chronic bullies, resulting in an overall decrease of

these behaviors.

One of the differences which produced a rather noteworthy

effect size was in regards to student perceptions of their peers

actions with regards to intervening in bullying. Effect sizes in the

moderate range are rare in research of this sort (Merrell, Gueldner,

Ross, & Isava, 2008) and so it is quite encouraging that students

indicated that following the intervention they observed that their

peers were much more willing to intervene in situations that they

recognized as bullying.

While the data on victimization and bullying were self-reports

from students and may be subject to bias, the data from staff

members with regards to student aggression would not reect this

bias. Although not all aggression is bullying, staff perceptions of

how students interact with each other does reect to some degree

the social climate of the school which is affected by all aggression

including bullying. Staff perceptions of students indicated that

there was less aggression following the intervention and that the

differences produced noteworthy effect sizes. The fact that staff

members observed less student aggression following the intervention supports the possibility that the reduction in self-reported

student bullying may have been an actual reduction as opposed to

one that occurred because of new awareness about the social

unacceptability of bullying behaviors. Again, it should be emphasized that bullying interventions seldom produce effect sizes of

even moderate magnitude, so it is encouraging that staff members

perceived a reduction in student aggression that was in the

moderate range.

Eliminating or reducing bullying is dependent on changing

adults as well as students, so this study sought to collect data on

staff differences following the intervention as compared to before

the intervention. It is noteworthy that staff members beliefs that

the schools efforts to deal with bullying were adequate, increased

signicantly and reected a minor to moderate effect size during

the time of the intervention. Likewise, the small but signicant

increase in staff members commitment to intervening in bullying

situations indicates that staff members have changed their

behaviors regarding how they address problems around bullying.

It is possible that these changes may have contributed to the

reported reduction in bullying and the observed decrease in

student aggression.

One of the challenges in bringing about change with respect to

this intervention is the fact that Meliora Public Academy is a very

safe school. This is reected in the low levels of physical bullying

and aggression reported by both students and staff, before as well

as after the intervention. Physical altercations on school property

average one or two over the course of a school year. Study data

indicate that the bullying and aggression that occurs tends to be of

a non-physical or social nature, and that when bullying takes place,

it is more covert and indirect. Throughout the data there is often

K.P. Allen / Studies in Educational Evaluation 36 (2010) 8392

little difference after the intervention as compared to before the

intervention because a high level of prosocial behavior and a low

level of antisocial behavior existed among students before the

intervention. This is not to suggest that bullying did not exist

before the intervention, or that it has subsequently been

eradicated. The ndings of a small amount of stable victimization

would preclude that position. However, given the absence of

confounding variables which cannot be ruled out because of the

study design, the results suggest that the intervention may have

contributed to some of the positive outcomes observed.

91

comparison group to ascertain causality. Additionally, it would be

benecial to replicate and evaluate this intervention in high

schools that are more representative of schools and communities

across the country.

Conclusion

The results of this evaluation suggest that bullying continues to

be an intervention issue into the high school years and that efforts

to counteract bullying at this level can be affected by designing and

implementing a school-wide system at this level.

Limitations

References

This study was limited by its before- and after-intervention

design. The fact that there was no control or comparison group

does not allow for conclusions regarding causality. Thus it cannot

be determined if the intervention produced the effects that were

observed or whether they were the result of other confounding

factors.

Another limitation of this study has to do with the fact that the

data were not repeated measures, thus reducing the statistical

power of the analysis and making interpretation of effect sizes

challenging. Additionally, due to some highly skewed data, this

study makes use of nonparametric analyses. Such analyses are not

as powerful as parametric analyses reducing the certainty with

which conclusions may be drawn.

One limitation of this study is that the intervention had only

been in place for two years when the post-intervention data were

collected. A longer pre- to post-assessment timeframe would have

given the program a longer time in which to make the types of

cultural and systemic changes that are needed for programs of this

sort to become rmly established. Ideally, a four year time span

would have been preferable because that would have allowed for

inclusion of students who came to the school as ninth graders

during the rst year of implementation with follow-up data being

collected during their last year (twelfth grade) at the school. This

group of students would have had a longer and stronger dosage

than the students who have been assessed for the current

evaluation, increasing the possibility that greater effects might

have resulted.

A further limitation of this study is that the second administration of the staff survey yielded 35% fewer completed surveys than

the rst administration. Attempts to include more staff members

were unsuccessful, so whereas the rst survey included approximately 78.0% of staff members, the second survey only reected

approximately 5.0% of the staff members. This may have affected

the reliability of the data.

Lastly, a nal limitation of this study is that the school where it

was conducted is not representative of high schools across the

United States. Meliora Public Academy resides in a wealthy

community, and the school itself is regarded as exemplary

because of its high academic standards and rigor. Thus,

generalizing these ndings to schools that do not t this prole

has its limitations.

Future directions

Bullying tends to be framed as a problem that diminishes as

students move into high school. The present study indicates that if

bullying does decrease in amount, it does not completely go away,

and in fact, this study conrms that bullying still exists at the high

school level. For this reason researchers should expand their

exploration of bullying to include the high school environment.

This study points to the possible effectiveness of a whole-school

bullying intervention at the high school level. Future research

could benet from a study design that includes a control or

Allen, K. P. (2009). Dealing with bullying and conict through a collaborative intervention process: The social and emotional learning intervention team. School Social

Work Journal, 33(2), 7085.

Allen, K. P. (2010). A bullying intervention system: Reducing risk and creating support

for aggressive students. Preventing School Failure, 54(3), 199209.

Atlas, R. S., & Pepler, D. J. (1998). Observations of bullying in the classroom. The Journal

of Educational Research, 92(2), 8699.

Baldry, A. C., & Farrington, D. P. (2007). Effectiveness of programs to prevent bullying.

Victims and Offenders, 2(2), 183204.

Boulton, M. J., & Smith, P. K. (1994). Bully/victim problems in middle school children.

British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 12, 315329.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature

and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Chapell, M. S., Hasselman, S. L., Kitchin, T., Lomon, S. N., MacIver, K. W., & Sarullo, P. L.

(2006). Bullying in elementary school, high school, and college. Adolescence,

41(164), 633648.

Chen, H. T., & Rossi, P. H. (1983). Evaluating with sense: The theory-driven approach.

Evaluation Review, 7(3), 283302.

Chen, H. T., & Rossi, P. H. (Eds.). (1992). Using theory to improve program and policy

evaluations. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Mahwah,

NJ: Erlbaum.

Connolly, J., Pepler, D., Craig, W., & Taradash, A. (2000). Dating experiences of bullies in

early adolescence. Child Maltreatment, 5(4), 299310.

Craig, W. M., & Pepler, D. J. (1997). Observations of bullying and victimization in the

school yard. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 13(2), 4160.

Donaldson, S. I. (2007). Program theory-driven evaluation science: Strategies and applications. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Donaldson, S. I., & Gooler, L. E. (2003). Theory-driven evaluation in action: Lessons from

a $20 million statewide Work and Health Initiative. Evaluation and Program

Planning, 26, 355366.

Frey, K. S., Hirschstein, M. K., Snell, J. L., Edstrom, L. V. S., MacKenzie, E. P., & Broderick, C.

J. (2005). Reducing playground bullying and supporting beliefs: An experimental

trial of the steps to respect program. Developmental Psychology, 41(3), 479491.

Gruber, J. E., & Fineran, S. (2008). Comparing the impact of bullying and sexual

harassment victimization on the mental and physical health of adolescents. Sex

Roles, 59, 113.

Kaukiainen, A., Salmivalli, C., Lagerspetz, K., Tamminen, M., Vauras, M., Maki, H., et al.

(2002). Learning difculties, social intelligence, and self-concept: Connections to

bully-victim problems. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 43, 269278.

Kim, Y. S., & Leventhal, B. (2008). Bullying and suicide: A review. International Journal of

Adolescent Medicine and Health, 20(2), 133154.

Klomek, A. B., Marrocco, F., Kleinman, M., Schonfeld, I. S., & Gould, M. S. (2007). Bullying,

depression, and suicidality in adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child

and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(1), 4049.

Kumpulainen, K. (2008). Psychiatric conditions associated with bullying. International

Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 20(2), 121132.

Leadbeater, B., Hoglund, W., & Woods, T. (2003). Changing contexts? The effects of a

primary prevention program on classroom levels of peer-relational and physical

victimization. Journal of Community Psychology, 31, 397418.

Linder, J. R., Crick, N. R., & Collins, W. A. (2002). Relational aggression and victimization

in young adults romantic relationships: Associations with perceptions of parent,

peer, and romantic relationship quality. Social Development, 11(1), 6986.

Madsen, K. C. (1996). Differing perceptions of bullying and their practical implications.

Educational and Child Psychology, 13(2), 1422.

Merrell, K. W., Gueldner, B. A., Ross, S. W., & Isava, D. M. (2008). How effective are

school bullying intervention programs? A meta-analysis of intervention research.

School Psychology Quarterly, 23(1), 2642.

Monks, C. P., & Smith, P. K. (2006). Denitions of bullying: Age differences in understanding of the term, and the role of experience. British Journal of Developmental

Psychology, 24, 801821.

Nansel, T. R., Overpeck, M., Pilla, R. S., Ruan, W. J., Simon-Morton, B., & Scheidt, P. (2001).

Bullying behaviors among U.S. youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. Journal of the American Medical Association, 285(16), 20942100.

OConnell, P., Pepler, D., & Craig, W. (1999). Peer involvement in bullying: Insights and

challenges for intervention. Journal of Adolescence 22 473-452.

Ofce of Educational Research & Improvements (2010). National Center for Education

Statistics. Core of Common Data. Retrieved from: National Center for Education

92

K.P. Allen / Studies in Educational Evaluation 36 (2010) 8392

Statistics, Ofce of Educational Research & Improvement: http://nces.ed.gov/ccd/

schoolsearch/school_detail.asp?Search+1&SchoolID=3623160032 41

Olweus, D. (1978). Aggression in the schools: Bullies and whipping boys. Washington, DC:

Hemisphere Publishing.

Olweus, D. (1991). Bully/victim problems among schoolchildren: Basic facts and effects

of a school based intervention program. In D. J. Pepler & K. H. Rubin (Eds.), The

development and treatment of childhood aggression (pp. 411448). Hillsdale, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum.

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Cambridge,

MA: Blackwell.

Olweus, D. (1996). Revised Olweus bully/victim questionnaire. Bergen, Norway: Research

Center for Health Promotion, University of Bergen.

Orpinas, P., Horne, A. M., & Staniszewski, D. (2003). School bullying: Changing the

problem by changing the school. School Psychology Review, 32(3), 431444.

Pepler, D. J., Craig, W. M., Ziegler, S., & Charach, A. (1994). An evaluation of an antibullying intervention in Toronto schools. Canadian Journal of Community Mental

Health, 13(2), 95110.

Pepler, D., Jiang, D., Craig, W., & Connolly, J. (2008). Developmental trajectories of

bullying and associated factors. Child Development, 79(2), 325338.

Porhola, M., Karhunen, S., & Rainivaara, S. (2006). Bullying at school and in the

workplace: A challenge for communication research. In C. S. Beck (Ed.), Communication Yearbook 30 (pp. 249301). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Rahey, L., & Craig, W. M. (2002). Evaluation of an ecological program to reduce bullying

in schools. Canadian Journal of Counselling, 36(4), 281296.

Rigby, K., & Slee, P. T. (1991). Bullying among Australian school children: Reported

behavior and attitudes towards victims. The Journal of Social Psychology, 131(5),

615627.

Rosenthal, A. (1991). Meta-analytic procedures for social research (revised). Newbury

Park, CA: Sage.

Salmivalli, C., & Kaukiainen, A. (2004). Female aggression revisited: Variable- and

person-centered approaches to studying gender differences in different types of

aggression. Aggressive Behavior, 30, 158163.

Salmivalli, C., & Nieminen, E. (2002). Proactive and reactive aggression among school

bullies, victims, and bully-victims. Aggressive Behavior, 28, 3044.

Smith, P. K. (2010). Bullying in primary and secondary schools: Psychological and

organizational comparisons. In S. R. Jimerson, S. M. Swearer, & D. L. Espelage (Eds.),

Handbook of bullying in schools: An international perspective (pp. 137150). New

York: Routledge.

Smith, P. K., Madsen, K. C., & Moody, J. C. (1999). What causes the age decline in reports

of being bullied at school? Towards a developmental analysis of risks of being

bullied. Educational Research, 41(3), 267285.

Smith, P. K., Ananiadou, K., & Cowie, H. (2003). Interventions to reduce school bullying.

Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 48(9), 591599.

Smith, J. D., Schneider, B. H., Smith, P. K., & Ananiadou, K. (2004). The effectiveness of

whole-school anti-bullying programs: A synthesis of evaluation research. School

Psychology Review, 33(4), 547560.

Solberg, M. E., & Olweus, D. (2003). Prevalence estimation of school bullying with the

Olweus bully/victim questionnaire. Aggressive Behavior, 29, 239268.

Sutton, J., Smith, P. K., & Swettenham, J. (1999). Social cognition and bullying: Social

inadequacy or skilled manipulation? British Journal of Developmental Psychology,

17, 435450.

Swearer, S. M., & Espelage, D. L. (2004). Introduction: A social-ecological framework of

bullying among youth. In D. L. Espelage & S. M. Swearer (Eds.), Bullying in schools: A

social-ecological perspective on prevention and intervention (pp. 112). Mahwah, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum.

Swearer, S. M., Espelage, D. L., Vaillancourt, R., & Hymel, S. (2010). What can be done

about school bullying?: Linking research to educational practice. Educational

Researcher, 39(1), 3847.

Tto, M. M., Farrington, D. P., & Baldry, A. C. (2008). Effectiveness of programmes to

reduce school bullying. Stockholm: Swedish Council for Crime Prevention, Information, and Publications.

Vossekuil, B., Fein, R., Reddy, M., Borum, R., & Modzeleski, W. (2002). The nal report and

ndings of the safe school initiative: Implications for the prevention of school attacks in

the United States. Washington, DC: United States Secret Service and United States

Department of Education.

Vreeman, R. C., & Carroll, A. E. (2007). A systematic review of school-based interventions to prevent bullying. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, 161, 7888.

Whitney, I., & Smith, P. K. (1993). A survey of the nature and extent of bullying in junior/

middle and secondary schools. Educational Research, 35, 325.

Yoon, J. S., Barton, E., & Taiariol, J. (2004). Relational aggression in middle school:

Educational implications of developmental research. Journal of Early Adolescence,

24(3), 303318.

Kathleen P. Allen is a doctoral candidate in the Human Development Program at the

University of Rochester, Margaret Warner Graduate School of Education and Human

Development. Her area of interest is bullying in schools.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Peer Leadership Peer Pressure & BullyingDocumento16 paginePeer Leadership Peer Pressure & BullyingNicholeNessuna valutazione finora

- Challenging Behaviour in Secondary SchooDocumento23 pagineChallenging Behaviour in Secondary Schoosuleman0% (1)

- Educ 500 Research ProposalDocumento14 pagineEduc 500 Research Proposalapi-282872818100% (1)

- Yanilda Goris - Trauma-Informed Schools Annotated BibliographyDocumento7 pagineYanilda Goris - Trauma-Informed Schools Annotated Bibliographyapi-302627207100% (1)

- Antibullying InterventionsDocumento22 pagineAntibullying InterventionsAliArSaNessuna valutazione finora

- Bullying in Schools: An Overview: HighlightsDocumento12 pagineBullying in Schools: An Overview: HighlightsMckevinSeguraNessuna valutazione finora

- College of Education: San Jose Community CollegeDocumento4 pagineCollege of Education: San Jose Community CollegeAnabel Jason Bobiles100% (3)

- FriendlySchoolsBullying J2011Documento26 pagineFriendlySchoolsBullying J2011MagdalenaRuizNessuna valutazione finora

- Bullying and Its EffectDocumento6 pagineBullying and Its EffectianNessuna valutazione finora

- Miriam Bullying Intervention in AdolesceDocumento13 pagineMiriam Bullying Intervention in AdolesceSalvador LópezNessuna valutazione finora

- The Effectiveness of Policy Interventions For School Bullying A Systematic ReviewDocumento25 pagineThe Effectiveness of Policy Interventions For School Bullying A Systematic RevieweticllacNessuna valutazione finora

- Alainne Cortez 2Documento14 pagineAlainne Cortez 2Allen CortezNessuna valutazione finora

- Understanding Classroom Bullying Climates: The Role of Student Body Composition, Relationships, and Teaching QualityDocumento14 pagineUnderstanding Classroom Bullying Climates: The Role of Student Body Composition, Relationships, and Teaching QualityMamaril Ira Mikaella PolicarpioNessuna valutazione finora

- A+Measure+of+the+Experience+of+Being+Bullied +An+Initial+Validation+in+Philippine+SchoolsDocumento14 pagineA+Measure+of+the+Experience+of+Being+Bullied +An+Initial+Validation+in+Philippine+SchoolsJuLievee Lentejas100% (1)

- What Can Be Done About School Bullying - Linking Research To Educational PracticeDocumento11 pagineWhat Can Be Done About School Bullying - Linking Research To Educational PracticeChrysse26Nessuna valutazione finora

- Engl108 Midterm ProjectDocumento6 pagineEngl108 Midterm ProjectPearl CollinsNessuna valutazione finora

- School Violence Prevention Current Status and Policy RecommendationsDocumento27 pagineSchool Violence Prevention Current Status and Policy RecommendationsAndreea NucuNessuna valutazione finora

- Guerra Et Al-2011-Child Development PDFDocumento16 pagineGuerra Et Al-2011-Child Development PDFMichael Stephen GraciasNessuna valutazione finora

- Zero Tolerance Policies in SchoolsDocumento10 pagineZero Tolerance Policies in SchoolsAylinNessuna valutazione finora

- Bullying: Recent Developments: Peter K. SmithDocumento6 pagineBullying: Recent Developments: Peter K. SmithPablo Di NapoliNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 s2.0 S0022440503000311 MainDocumento22 pagine1 s2.0 S0022440503000311 MainAzmil XinanNessuna valutazione finora

- Polanin Espelage Pigott 2012 A Meta-Analysis of School-Basd Bullying Prevention Programs Effects On Bystander Intervention BehaviorDocumento21 paginePolanin Espelage Pigott 2012 A Meta-Analysis of School-Basd Bullying Prevention Programs Effects On Bystander Intervention BehaviorANDREZ ARTURO �AHUI MELCHORNessuna valutazione finora