Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

ARC2AZT - Life, Death and Chocolate in Mesoamerica The Aztecs and The Maya Where Did The Ritual Use of Cacao Originat

Caricato da

pilarphsmithTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

ARC2AZT - Life, Death and Chocolate in Mesoamerica The Aztecs and The Maya Where Did The Ritual Use of Cacao Originat

Caricato da

pilarphsmithCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Life, Death and Chocolate in Mesoamerica:

The Aztecs and the Maya; Where did the Ritual Use of Cacao Originate?

ARC2AZT

Caroline Seawright

2012

http://www.thekeep.org/~kunoichi/kunoichi/themestream/ARC2AZT.html

Caroline Seawright

Life, Death and Chocolate in Mesoamerica

Ritual use of cacao permeates the Maya, the Aztec, and other cultures of Mesoamerica.

Cacao, an indigenous plant, originally appeared in the Soconusco region of Mexico, with

archaeological evidence of its use stretching over millennia. Next to maize, it was the most

important plant food in Mesoamerica. Cacao connected mankind to their gods; it was used

as a milestone for important life events, a healing beverage, and a luxury. This essay will

investigate the archaeological and ethnohistorical history of cacao in rituals and religion,

and its origin. The similarities in cacao rites associated with various milestones of the

lifecycle of indigenous peoples, and the symbolism of cacao and its use with human

sacrificial rituals, in religion and at death, will be explored, focusing on the Maya, the Aztec

and other cultures (Figure 1). Cacao has permeated the ritual life of the Mesoamerican

people since ancient times. Despite the millennia that have passed, and the different

cultures that procured cacao, there is a remarkable similarity in ritual contexts. It is

postulated that cacao must have originated from an early culture, stemming back to the

time of the Olmecs.

Figure 1: Mesoamerican timeline (Pohl 2003).

Caroline Seawright

Life, Death and Chocolate in Mesoamerica

The Maya and the Aztecs were instrumental in introducing cacao to the Spanish, yet as

cacao originated far to the south in Soconusco, another culture must have introduced it to

them. Within the Maya region, vessels containing theobromine, an alkaloid found in cacao,

have been discovered at Colha in Belize from the Pre-Classic period (c. 600 BC-250 AD),

and from a Classic period tomb at Rio Azul in Guatemala (c. 460-480 AD; Figure 2);

iconographic and ethnographic evidence demonstrates the cultural importance of cacao to

the Maya through the Classic (c. 250-900 AD) and into the Post-Classic (c. 900-1,500 AD)

periods (Hall et al. 1990, p. 139-140; Kufer, Grube and Heinrich 2006, p. 598; Powis et al.

2008, pp. 35-36; Figure 3). Five rare cacao seeds (c. 134-615 AD) were discovered in an

Early Classic Maya burial at Batsub Cave, Belize (McNeil 2010, p. 310; Moreiras 2010, p.

19; Prufer and Hurst 2007, pp. 276-278). As few studies were apparently performed on the

theobromine contents of vessels from within the Aztec sphere of influence, archaeologists

rely on iconographic and ethnographic descriptions to determine the nature of such

vessels. For example, Smith et al. (2003, p. 3 & 257) believe that a polished redware

goblet with a butterfly element (c. 1350-1520 AD; Figure 4), found at a Coatetelco burial,

was used for drinking cacao as it is similar in style to the picture of a similar cacao vessel

with a bird element (Figure 5) in the Codex Tudela. They also contend that the shape of

Mixtec cacao serving vessels differ from shape to those used by the Aztecs (Smith et al.

2003, p. 262). Direct evidence from the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan is hard to find, due to

Mexico Citys location on top of the old capital, and no evidence of cacao has been found

within the citys old ritual centre (Draper 2010, p. 110; Templo Mayor Museum 2012 pers.

comm., 10 May). Ceramics containing cacao traces (c. 1,000-1,125 AD) have even been

found as far away as Pueblo Bonito in the Chaco Canyon, USA (Moreiras 2010, p. 21;

Map 2). Cacao has been important since at least 600 BC, which suggests that the

Mesoamerican origin of cacao use came from a time prior to that of the Maya. The ritual

use of cacao must therefore be examined before a common origin can be determined.

2

Caroline Seawright

Life, Death and Chocolate in Mesoamerica

Map 1: Mesoamerican sites with evidence of cacao, including Pueblo Bonito in New

Mexico (Moreiras 2010, p. 39).

Figure 2: Ceramic vessels from Rio Azul with cacao residues (Hall et al. 1990, p. 139).

3

Caroline Seawright

Life, Death and Chocolate in Mesoamerica

Figure 3: Behind God L, a woman pours chocolate from one vessel into another.

Princeton Vase, Late Classic Maya (c. 750 AD) (Kerr 2005a; Moreiras 2010, p. 37).

Figure 4: Polished redware goblet from

Coatetelco, probably used for drinking

cacao (after Smith et al. 2003, p. 259).

Figure 5: Woman pouring cacao, Codex

Tudela (NEH Summer Institute for School

Teachers, Oaxaca 2011a).

4

Caroline Seawright

Life, Death and Chocolate in Mesoamerica

According to the beliefs of the Maya and Aztec, cacao was part of the creation myth and

thus the start of life. In Post-Conquest literature, the K'iche' Maya Popol Vuh and the Aztec

Chimalpopoca Codex, the gods alternatively created man from maize, cacao and other

good plant foods, or brought the same foods to mankind from the mythical Mountain of

Sustenance (Coe and Coe 1996, pp. 41-42; Dillinger et al. 2000, p. 2058S; Recinos 1950,

p. 166; Suess 2002, p. 21). Although these works were written after the Spanish

Conquest, they show how mankind connects to the divine through the use of cacao. This

connection began at birth, and continued throughout life. In the 16th Century, Diego Garca

de Palacio observed a Maya naming ritual where the priest and mother presented cacao to

the newly named baby (Henderson et al. 2007, p. 18938; Prufer and Hurst 2007, p. 288).

Bishop Diego de Landa describes the Post-Conquest Maya baptising children with a

mixture of cacao, virgin water and crushed flowers during an initiation ceremony (Vail

2009, p. 5). Friar Bernardino de Sahagn describes 16th century Aztec fathers advising

their sons, who were entering religious school, to offer cacaoatl drink to God (DurandForest 1967, pp. 174). Cacao use also occurred in marriage ceremonies. The 14th century

Codex Zouche-Nuttall depicts a Mixtec ceremony where Lady Thirteen Serpent offers a

bowl of cacao to Lord Eight Deer to solemnise their marriage (Closs 2000, p. 230; Vail

2009, p. 6; Figure 6). The Post-Conquest Madrid Codex depicts the Maya god Chaak

marrying the goddess Ixik Kaab, stating that they were given their cacao, a term

indicating marriage (Figure 7); in the Guatemalan highlands, some Maya continue to hold

to this tradition (Vail 2009, pp. 6-7), although some cultures now use money in place of

cacao. Chocolate still resonates with indigenous ceremonies today as it has done since

much earlier times (Coe and Coe 1996, pp. 62-63; LeCount 2001, p. 943; Prufer and Hurst

2007, pp. 286-287). Cacao was also used at religious rites and festivals, and as a symbol

of blood itself.

5

Caroline Seawright

Life, Death and Chocolate in Mesoamerica

Figure 6: The groom, Lord Eight Deer, points to a cup of frothy cacao in the hands of his

bride, Lady Thirteen Serpent (Mexico Lore 2006).

Figure 7: The wedding of the god Chaak and the goddess Ixik Kaab (NEH Summer

Institute for School Teachers, Oaxaca 2011b).

6

Caroline Seawright

Life, Death and Chocolate in Mesoamerica

The symbolism of chocolate as blood was universal throughout Mesoamerica. The Madrid

Codex depicts four young Maya gods piercing their own earlobes to cover cacao pods in

showers of their own blood because the Maya linked liquid chocolate with blood (Coe and

Coe 1996, p. 44-45; Dillinger et al. 2000, p. 2058S; Figure 8). Landa (1937, pp. 86-89)

discusses the cruel and obscene sacrifices made by the Maya, but cacao is not identified

as being part of any human sacrificial rituals. The connection between blood and chocolate

also mattered to the Aztecs, for whom the metaphor "heart, blood" meant cacao, and the

cacao pod was likened to the human heart torn out in sacrifice (Coe and Coe 1996, p. 101;

Moreiras 2010, p. 32). The Aztecs also occasionally offered cacao to sacrificial victims.

This was offered to comfort human sacrifices to the trader god Yacatecuhtli (Dillinger et

al. 2000, p. 2058S; Figure 9), and was a major ingredient in itzpacalatl (water from the

washing of obsidian blades) which was given to the impersonator of Quetzalcoatl. This

concoction perhaps with additional unnamed hallucinogens would ensure that he was

joyful until the time of his death (Coe and Coe 1996, p. 102; Durn 1971, pp. 131-133;

Elferink 1988, p. 430-431; Versnyi 1989, pp. 218-219). To the Maya, cacao was a sacred

offering to the gods combined with personal blood-letting through the piercing or cutting of

their own flesh. Unlike the Aztecs, there is no evidence that cacao was part of Maya

human sacrifice rites. Whilst the Aztecs used cacao to subdue victims for sacrifice, it was

not part of the ceremony itself as only the heart was offered to the deities. The association

between cacao and blood, which survived through thousands of years of cultural change,

must have originated from potent beliefs and symbolism of an ancestral culture. Although

the Spanish outlawed human sacrifice in Mesoamerica and brought change to the religions

of the area, blood and chocolate continued to be central to the worship the old gods.

Caroline Seawright

Life, Death and Chocolate in Mesoamerica

Figure 8: Gods cutting their ears and bleeding onto cacao pods (FAMSI 2003).

Figure 9: The Aztec merchant god Yacatecuhtli, as depicted in the Codex FejrvryMayer (Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt Graz 2004).

Caroline Seawright

Life, Death and Chocolate in Mesoamerica

The religions of the Maya and Aztec were similar, as were their ways of revering their

gods. The Maya deity of merchants and cacao, known as Ek Chuah during the PostConquest period, had links to the Aztec merchant deity, Yacatecuhtli (Guerrero 2009, p.

1194; Vail 2009, p. 6), because cacao was used as currency (Landa 1937, pp. 71). During

the month of Muan, cacao plantation owners offered a dog spotted with the colours of the

cacao in sacrifice to certain gods, including Ek Chuah (Aguilera 1985, p. 120; Dillinger et

al. 2000, p. 2058S; Landa 1937, p. 131; Vail 2009, pp. 4-5). Sahagn documents PostConquest Aztec offerings of liquid chocolate in sacred cups to Xiuhtecutli, the old fire god,

and to Yiacatecutli, by merchants who had returned from long journeys (Durand-Forest

1967, p. 174; Sahagn 1976, p. 28). The Aztecs maintained trade links with the cacaoproducing Maya city of Acallan (Coe and Coe 1996, p. 59). Through such networks, the

Maya adopted a new deity of merchants and cacao, known as God M (Figure 10), who

had the attributes of Yacatecuhtli (Taube 1992, p. 88). The Maya Maize God also had a

connection to these merchant gods, and to chocolate; he is occasionally shown as having

cacao pods growing from his body (Figure 11), having been, on his death, transformed into

plant foods, cacao being the most prominent after maize (Martin 2006, pp. 154-156 &

163). God L presided over the Maize Gods death and took possession of these crops,

including cacao (Martin 2006, pp. 169). A mural of God L facing a cacao tree (c. 600-830

AD; Figure 12) was discovered at Cacaxtla, a central Mexican site which flourished prior to

the arrival of the Aztecs (Dakin and Wichmann 2000, p. 68). The mural was painted in

Maya-Mexican style at the bottom of a stairway to symbolise the ascent of God L from the

underworld, ladened with maize and cacao (Coe and Coe 1996, p. 56; Martin 2006, p.

172; Vail 2009, p. 6). This belief in the Maize God is even more ancient (Taube 1996).

Despite religious changes across time and culture, the religious importance of cacao never

diminished.

9

Caroline Seawright

Life, Death and Chocolate in Mesoamerica

Figure 10: Cacaxtla mural, God L at a cacao tree (Dreiss and Greenhill 2008, pp. 90-91).

Figure 12: Bowl depicting the Maize God as a

personified cacao tree (250-600 AD) from the

Dumbarton Oaks Collection (Stone and Kreft

2005).

Figure 11: Late Classic vase (600900 AD) with possible depiction of

God M (Prez de Lara 2007).

10

Caroline Seawright

Life, Death and Chocolate in Mesoamerica

Beyond ethnohistorical sources and surviving codices, the best source of evidence for

ritual use of cacao is Mesoamerican tombs. Prufer and Hurst (2007, p. 289) note that

cacao is an important part of mortuary rituals for the dead and the living: it could be an

offering to accompany the deceased into the afterlife, and it may be consumed by the

living during funeral preparations. The Maya were carefully buried with personalised cacao

cups. The text around the rim known as the Primary Standard Sequence includes the

name of the deceased and the type of cacao the cup contained (LeCount 2001, p. 945;

Moreiras 2010, p. 19; Figure 13). The seeds found at Batsub Cave (c. 134-615 AD) were

in an inverted bowl over the pelvis of a decapitated individual. In the position where his

head should have been was an undecorated jar containing a single jade bead, and his

actual head was lying to the left of his pelvis (Prufer and Hurst 2007, pp. 276-278). The

body was near a wooden stool, which Prufer and Hurst (2007, p. 289) assert is an

important part of ritual mortuary activity. Theobromine residue has been found in burial

offering vessels at Copan (c. 430-600 AD; Figure 14), mixed with inedible cinnabar

pigment to differentiate cacao drinks for the deceased from the consumable beverages of

the living (McNeil 2010, p. 300 & 306). As no theobromine studies of Aztec burial vessels

are available, ethnohistorical information shows that Aztecs drank cacao from cups called

copa (Nichols et al. 2009, p. 459). An image from the Codex Magliabechiano, an early

Post-Conquest codex, describes a high ranking individuals funeral where his relatives

offer him cacauatl (chocolate) for the journey (Iguaz 1993, p. 64; Figure 15). Friar Diego

Durn described that, following the death of king Axayacatl in 1481, the deceased ruler

was presented with slaves, cacao and other precious items for his use in the afterlife. After

his body had been dressed in imitation of the gods, his wives brought him offerings of

foods and gourds filled with chocolate (Durn 1994, pp. 293-294). Earlier cultures also had

cacao, but there is only archaeological evidence of one ancient culture in a ritual setting.

This legacy survives through to the present Maya and Aztec ritual uses of cacao.

11

Caroline Seawright

Life, Death and Chocolate in Mesoamerica

Figure 13: Cacao cup stating the name Lady Bacab of Tikal (Kerr 2005b).

Figure 15: Relatives of the deceased offer the

deceased chocolate for his journey into the

afterlife, from the Codex Magliabechiano

Figure 14: The Dazzler Vase (c. 430-

(Iguaz 1993, p. 68).

600 AD), a cylinder tripod vessel from

the Margarita tomb at Honduras with

evidence

of

cacao

(Xian

2012a).

12

Caroline Seawright

Life, Death and Chocolate in Mesoamerica

The use of cacao in ritual throughout Mesoamerica varies through time and space (Prufer

and Hurst 2007, p. 285), but the number of similarities suggests a common origin. Early

archaeological evidence of Mesoamerican cacao usage has been detected through traces

of theobromine on ancient ceramics (Moreiras 2010, p. 6). Site assemblages include a jar

(Figure 16) from the pre-Olmec Mokaya culture at Paso de la Amada, a bowl found in at El

Manat, various vessels of different shapes (Figure 17) from the Olmec capital of San

Lorenzo, and a number of Olmec-style ceramic bowls and other vessels at the Early

Honduran site of Puerto Escondido in Honduras (Henderson et al. 2007, p. 18938; Joyce

and Henderson 2007, p. 645; Moreiras 2010, p. 17; Powis et al. 2008, p. 36-37; Powis et

al. 2011, p. 8595; Map 2; Table 1). The Mokaya, Corn People, were one of the earliest

Mesoamerican egalitarian societies to become stratified during the Early Formative period

(Clarke and Blake 1994, p. 22). Although Mokaya and Early Honduran ritual use of cacao

cannot be determined from the location of the artefacts, Clarke and Blake hypothesise

(1994, p. 28) that this style of ceramics was designed for liquids with ritual and prestige

value. The word for cacao itself, however, came from the Olmec heartland (Kaufman and

Justeson 2007, p. 193), suggesting that it was held in high status among the Olmecs, and

those who subsequently appropriated the word, and the product, for their own usage. The

El Manat bowl, found amongst religious offerings, is indicative of the ritual importance of

cacao (Powis et al. 2008, p. 37), as is a San Lorenzo burial pit for the victims of human

sacrifice, capped with four cacao-filled vessels (Powis et al. 2011, p. 8597 & 8599).

Mesoamerica had a very long, continuous history of preparing and consuming liquid

chocolate ... chocolate drink was as central to the Mokaya and Olmec as we know it was

to the later Maya and Aztecs (Powis et al. 2008, p. 38). Of these early cultures, the

Olmecs are the most probable culture to have disseminated cacao throughout

Mesoamerica, along with their cultural, religious and social practices (Joyce and

Henderson 2010, p. 197; Tolstoy and Paradis 1970, p. 350).

13

Caroline Seawright

Life, Death and Chocolate in Mesoamerica

Figure 16: Fragment of the vessel from Paso de la Amada (Xian 2012b).

Figure 17: Vessels from the San Lorenzo used for cacao (Powis et al. 2011, p. 8599).

Map 2: Locations of early archaeological sites with cacao (Powis et al. 2011, p. 8596).

14

Caroline Seawright

Life, Death and Chocolate in Mesoamerica

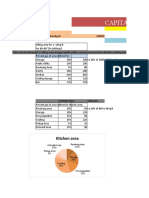

Culture

Mokaya

Olmec

Olmec

Site

Paso de la Amada

El Manat

San Lorenzo

Stratigraphy

Construction fill deposit

Ritual context, with luxury offerings

Domestic and ceremonial contexts

Early Honduran

Puerto Escondido

Two different domestic contexts

Description

Tecomate jar, vertical fluting

Deep bowl, red slip line at base

Caamao jar, course

Caimn bottle, polished

Conejo open bowl, orange-on-white

Eroded necked jar, grey

Garza neckless jar, smooth

Mulato cup, black

Peje micaceous closed form

Pochitoca bottle, polished

Tejn rimmed bowl, white

Tejn open vessel, white

Tejn open bowl, white

Tigrillo rimmed bowl, black and white

Tigrillo open bowl, black and white

Tigrillo ladle, monochrome

Tigrillo open bowl, monochrome

Tigrillo small cup, monochrome

Tigrillo rimmed bowl, white-rimmed

black

Xochiultepec collared jar, white

Xochiultepec necked jar, white

Xochiultepec open bowl, white

Various open bowls, flaring walls (x 7)

Black base of cylinder, glossy

Urbe unslipped jar, pattern burnishing

Barraca bottle spout, glossy

Date

c. 1,900-1,500 BC

c. 1,650-1,500 BC

c. 1,800-1,600 BC

c. 1,400-900 BC

Table 1: Early archaeological vessels with evidence of cacao from Mesoamerican sites (after Henderson et al. 2007, p. 18938; Joyce

and Henderson 2007, p. 645; Moreiras 2010, p. 17; Powis et al. 2008, p. 36-37; Powis et al. 2011, p. 8595).

15

Caroline Seawright

Life, Death and Chocolate in Mesoamerica

Despite cultural changes over time and space throughout Mesoamerica, resulting in

different ritual use of chocolate, cacao was the second most important plant to the various

cultures of Central America. The Maya and the Aztecs used cacao in coming-of-age and

wedding customs; and as liquid offerings for the gods due to its symbolic connections with

blood. Both cultures used different methods to prepare people for sacrifice the Aztecs

occasionally gave cacao to the victims, whereas the Maya did not. They both presented

cacao to the dead for use in the afterlife. Although evidence as to whether the Olmec

associated chocolate with lifecycle milestones and religion is lacking, cacao was clearly an

important product as they, too, provided their dead with cacao for their journey into the

underworld. Based on this evidence, cacao was first used in a ritual manner by the

Olmecs. To more satisfactorily answer this question, research is required on the status of

cacao in the Olmec religion domain, and on the theobromine content in Aztec ceramics.

Chocolate was the foremost plant food, after maize, used ritually in almost every aspect of

the lives of the peoples of Mesoamerica. It is a mysterious product, rendered sacred, but

for reasons never clearly stated ... Linked to the earth and the cyclical nature of human life,

it both mediates and transcends relationships between humans and the forces that

animate the earth (Prufer and Hurst 2007, p. 292). The use of cacao may have changed

throughout history, but it has always retained its place of importance to the peoples of

Mesoamerica, thanks to the ancient Olmec.

16

Caroline Seawright

Life, Death and Chocolate in Mesoamerica

Aguilera, C 1985, Flora y Fauna Mexicana: Mitologa y Tradiciones, University of Texas,

Mexico.

Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt Graz 2004, Yacatecuhtli, Codex Fejrvry-Mayer,

image, Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies Inc, viewed 14 May

2012, <http://www.famsi.org/research/graz/fejervary_mayer/img_page30.html>.

Clarke, JE & Blake, M 1994, The Power of Prestige: Competitive Generosity and the

Emergence of Rank Societies in Lowland Mesoamerica, in EM Brumfiel and JW Fox

(eds), Factional Competition and Political Development in the New World, Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge, pp. 17-30.

Closs, M 2000, Mesoamerican Mathematics, in H Selin (ed), Mathematics Across

Cultures: The History of Non-Western Mathematics, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Great

Britain, pp. 205-238.

Coe, SD & Coe, MD 1996, The True History of Chocolate, Thames and Hudson, New

York.

Dakin, K & Wichmann, S 2000, Cacao and Chocolate: A Uto-Aztecan Perspective,

Ancient Mesoamerica, vol. 11, pp. 55-75.

Dillinger, TL, Barriga, P, Escrcega, S, Jimenez, M, Lowe, DS, & Grivetti, LE 2000, Food

of the Gods: Cure for Humanity? A Cultural History of the Medicinal and Ritual Use of

Chocolate, The Journal of Nutrition, vol. 130, no. 8S, pp. 2057S-2072S.

Draper, R 2010, Unburying the Aztec, National Geographic, vol. 218, no. 5, pp. 110-135.

Dreiss, L, & Greenhill, SE 2008, Chocolate: Pathway to the Gods, University of Arizona

Press, China.

Durn, D 1971, Book of the Gods and Rites and the Ancient Calendar, trans. F Horcasitas

and D Heyden, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma.

Durn, D 1994, The History of the Indies of New Spain, trans. D Heyden, University of

Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma.

17

Caroline Seawright

Life, Death and Chocolate in Mesoamerica

Durand-Forest, J 1967, El Cacao Entre Los Aztecas, Estudios de Cultura Nhuatl, vol.7,

pp. 155-181.

Elferink, JGR 1988, Some Little-Known Hallucinogenic Plants of the Aztecs, Journal of

Psychoactive Drugs, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 427-435.

FAMSI 2003, Four gods bleeding onto cacao pods from the Madrix Codex, image,

Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies Inc, viewed 10 May 2012,

<http://www.famsi.org/mayawriting/codices/madrid.html>.

Guerrero, AM 2009, Ek Chuah, Deidad Identificada Principalmente por Fuentes

Coloniales del Centro de Mxico: Similitudes Iconogrficas, XXII Simposio de

Investigaciones Arqueolgicas en Guatemala, pp. 1193-1199.

Hall, GD, Tarka Jr., SM, Hurst, WJ, Stuart, D & Adams REW 1990, Cacao Residues in

Ancient Maya Vessels from Rio Azul, Guatemala, American Antiquity, vol. 55, no. 1, 138143.

Henderson, JS, Joyce, RA, Hall, GR, Hurst, WJ, & McGovern, PE 2007, Chemical and

Archaeological Evidence for the Earliest Cacao Beverages, Proceedings of the National

Academy of Sciences, vol. 104, no. 48, pp. 18937-18940.

Iguaz, D 1993, Mortuary Practices Among the Aztec in the Light of Ethnohistorical and

Archaeological Sources, Papers from the Institute of Archaeology, vol. 4, pp. 63-76.

Joyce, RA, & Henderson, JS 2007, From Feasting to Cuisine: Implications of

Archaeological Research in an Early Honduran Village, American Anthropology, vol. 109,

no. 4, pp. 642-653.

Joyce, RA, & Henderson, JS 2010, Being Olmec in Early Formative Period Honduras,

Ancient Mesoamerica, vol. 21, pp. 187-200.

Kaufman, T, & Justeson, J, 2007, The History of the Word for Cacao in Ancient

Mesoamerica, Ancient Mesoamerica, vol. 18, pp. 193-237.

18

Caroline Seawright

Life, Death and Chocolate in Mesoamerica

Kerr, J 2005a, MayaVase Hi-Resolution for Vase K511, image, Maya Vase Database,

viewed 10 May 2012, <http://research.mayavase.com/kerrmaya_hires.php?vase=511>.

Kerr, J 2005b, MayaVase Hi-Resolution for Vase K 1941, image, Maya Vase Database,

viewed 15 May 2012, <http://research.mayavase.com/kerrmaya_hires.php?vase=1941>.

Kufer, J, Grube, N, & Heinrich, M 2006, Cacao in Eastern Guatemala a Sacred Tree

with Ecological Significance, Environ Dev Sustain, vol. 8, pp. 597-608.

Landa, D 1937, Yucatan Before and After the Conquest: The Maya, trans. W Gates,

Forgotten Books 2008.

LeCount, LJ 2001, Like Water for Chocolate: Feasting and Political Ritual among the Late

Classic Maya at Xunantunich, Belize, American Anthropologist, vol. 103, no. 4, pp. 935953.

Martin, CL 2006, Cacao in Ancient Maya Religion: First Fruit from the Maize Tree and

Other Tales from the Underworld, in CL McNeil (ed), Chocolate in Mesoamerica: A

Cultural History of Cacao, University Press of Florida, Gainesville, pp. 155-183.

McNeil, CL 2010, Death and Chocolate: The Significance of Cacao Offerings in Ancient

Maya Tombs and Caches at Copan, Honduras, in JE Staller and MD Carrasco (eds), PreColumbian Foodways: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Food, Culture, and Markets in

Ancient Mesoamerica, Springer, New York, pp. 293-314.

Mexico Lore 2006, wedding of Eight Deer & Thirteen Serpent, image, Mexico Lore, viewed

12 May 2012, <http://www.mexicolore.co.uk/index.php?one=azt&two=ask&tab=ans&id=21>.

Moreiras, DK 2010, Thinking and Drinking Chocolate: The Origins, Distribution, and

Significance of Cacao in Mesoamerica, Honours thesis, University of British Columbia,

Vancouver.

NEH Summer Institute for School Teachers, Oaxaca 2011a, woman pouring cacao from

the Tudela Codex, image, National Endowment for the Humanities, viewed 12 May 2012,

<http://whp.uoregon.edu/mesoinstitute/?page_id=759>.

19

Caroline Seawright

Life, Death and Chocolate in Mesoamerica

NEH Summer Institute for School Teachers, Oaxaca 2011b, wedding of the god Chaak

and the goddess Ixik Kaab, image, National Endowment for the Humanities, viewed 12

May 2012, <http://whp.uoregon.edu/mesoinstitute/?page_id=759>.

Nichols, DL, Elson, C, Cecil, LG, Neivens de Estrada, N, Glascock, MD & Mikkelsen, P

2009, Chiconautla, Mexico: A Crossroads of Aztec Trade and Politics, Latin American

Antiquity, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 443-472.

Prez de Lara, G 2007, possible depiction of God L on a Late Classic vase from Jaina

island, image, Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies Inc. (FAMSI),

viewed 15 May 2012 <http://www.mesoweb.com/features/jpl/54.html>.

Pohl, J 2003, timeline of major cultures of Mesoamerica, image, Foundation for the

Advancement

of

Mesoamerican

Studies

Inc.

(FAMSI),

viewed

12

May

2012,

<http://www.famsi.org/research/pohl/chronology.html>.

Powis, TG, Cyphers, A, Gaikwad, NW, Grivetti, L, & Cheong, K 2011, Cacao Use and the

San Lorenzo Olmec, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 108, no. 21,

pp. 8595-8600.

Powis, TG, Hurst, WJ, del Carmen Rodrguez, M, Ortiz C., P, Blake, M, Cheetham, D,

Coe, MD, & Hodgeson, JG 2008, The Origins of Cacao Use in Mesoamerica, Mexicon,

vol. 30, pp. 35-38.

Prufer, KM, & Hurst, WJ 2007, Chocolate in the Underworld Space of Death: Cacao

Seeds from an Early Classic Mortuary Cave, Ethnohistory, vol. 54, no. 2, pp. 273-301.

Recinos, A 1950, Popol Vuh: The Sacred Book of the Ancient Quich Maya, trans D Goetz

and SG Morley, Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma.

Smith, ME 2003, Decorated Serving Vessels from Postclassic Burial Offerings in Morelos,

Mexicon, vol. 25, p. 3.

20

Caroline Seawright

Life, Death and Chocolate in Mesoamerica

Smith, ME, Wharton, JB, & Olson, JM 2003, Aztec Feasts, Rituals, and Markets: Political

Uses of Ceramic Vessels in a Commercial Economy, in TL Bray (ed), The Archaeology

and Politics of Food and Feasting in Early States and Empires, Kluwer Academic/Plenum

Publishers, New York.

Stone, A, and Kreft, L 2005, depiction of Chocolate god on bowl, image, LindaKreft.com,

viewed 14 May 2012, <http://www.lindakreft.com/Mesoamerica/cacao.html>.

Suess, P 2002, La Conquista Espiritual de la Amrica Espaola: 200 Documentos-Siglos

XVI, Editorial Abya Yala, Ecuador.

Taube, KA 1992, The Major Gods of Ancient Yucatan, Dumbarton Oaks, USA.

Taube, KA 1996, The Olmec Maize God: The Face of Corn in Formative Mesoamerica,

RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, vol. 29/30, pp. 39-81.

Tolstoy, P, and Paradis, LI 1970, Early and Middle Preclassic Culture in the Basin of

Mexico: Revision of the Preclassic Sequence gives New Perspective on Olmec Presence

in the Central Highlands., Science, vol. 167, pp. 344-351.

Vail, G 2009, Cacao Use in Yucatn Among the Pre-Hispanic Maya, in LE Grivetti and HY Shapiro (eds), Chocolate: History, Culture, and Heritage, John Wiley & Sons Inc.,

Hoboken, New Jersey, pp. 3-15.

Versnyi, A 1989, Getting under the Aztec Skin: Evangelical Theatre in the New World,

New Theatre Quarterly, vol. 5, no. 19, pp. 217-226.

Xian, M 2012a, The Dazzler Vase from the royal Margarita Tomb in Copn, Honduras,

image, C-Spot, viewed 14 May 2012, <http://www.c-spot.com/atlas/historical-timeline/>.

Xian, M 2012b, fragment of the shard from Paso de la Amada, image, C-Spot, viewed 14

May 2012, <http://www.c-spot.com/atlas/historical-timeline/>.

21

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Ethnic American Cooking - Recipes For Living in A New WorldDocumento358 pagineEthnic American Cooking - Recipes For Living in A New WorldKonstantinos Alexiou100% (1)

- Divination Herbs TechniqueDocumento3 pagineDivination Herbs Techniquetower1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Decapitación en Cupisnique y Moche A Cordy-Collins (1992)Documento16 pagineDecapitación en Cupisnique y Moche A Cordy-Collins (1992)Gustavo M. GarciaNessuna valutazione finora

- Maya Culture The MayaDocumento9 pagineMaya Culture The MayaAna IrinaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Recipe For RebirthDocumento71 pagineThe Recipe For RebirthWalter SánchezNessuna valutazione finora

- Tracing The History of The Human Skull IDocumento49 pagineTracing The History of The Human Skull ISoporte CeffanNessuna valutazione finora

- Mayan Civilization: A History From Beginning to EndDa EverandMayan Civilization: A History From Beginning to EndValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (6)

- The Aztecs - What Should History SayDocumento6 pagineThe Aztecs - What Should History Saywelcome hereNessuna valutazione finora

- Tracing The History of The Human Skull IDocumento49 pagineTracing The History of The Human Skull IJelena Jasic100% (1)

- Viracocha Kukulkan QuetzalcoatlDocumento15 pagineViracocha Kukulkan QuetzalcoatlRajendran NarayananNessuna valutazione finora

- Mushroom WarriorDocumento107 pagineMushroom WarriorJohn Pugno100% (2)

- Aztec MythologyDocumento38 pagineAztec MythologyMundalah EpifaniaNessuna valutazione finora

- Under Her Towle Samantha 2017 Annas Archive Libgenrs Fic 2013042 PDFDocumento217 pagineUnder Her Towle Samantha 2017 Annas Archive Libgenrs Fic 2013042 PDFMaithri MurthyNessuna valutazione finora

- Lord of the Dawn: The Legend of QuetzalcóatlDa EverandLord of the Dawn: The Legend of QuetzalcóatlValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (2)

- Martha's Easy Basic Pancake RecipeDocumento37 pagineMartha's Easy Basic Pancake Recipekrishna kumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Vata Constitution AyurvedaDocumento11 pagineVata Constitution AyurvedaElla Miu100% (1)

- Georgia A History of WineDocumento2 pagineGeorgia A History of WineGeorgian National MuseumNessuna valutazione finora

- Mesoamerica Ancient Civilizations NotesDocumento6 pagineMesoamerica Ancient Civilizations Noteslovely joy banaybanayNessuna valutazione finora

- Dominos Competitor and Consumer Insights AnalysisDocumento25 pagineDominos Competitor and Consumer Insights AnalysisMonilGuptaNessuna valutazione finora

- Fermentation SystemsDocumento40 pagineFermentation SystemsLolly AntillonNessuna valutazione finora

- Periodical Test - TLE 10 1st GradingDocumento3 paginePeriodical Test - TLE 10 1st GradingLOVELY DELA CERNANessuna valutazione finora

- The Night Is Short, Walk On Girl - 2Documento199 pagineThe Night Is Short, Walk On Girl - 2Kafka ErgensNessuna valutazione finora

- Cultural History of The Ritual & Mediciinal Uses of Chocolate PDFDocumento16 pagineCultural History of The Ritual & Mediciinal Uses of Chocolate PDFMichel RigaudNessuna valutazione finora

- Chocolate, Sex, and Disorderly Women in Late-Seventeenth-and Early-Eighteenth-Century GuatemalaDocumento15 pagineChocolate, Sex, and Disorderly Women in Late-Seventeenth-and Early-Eighteenth-Century GuatemalaMéxico tiempoNessuna valutazione finora

- Gutiérrez, B.A. (2002) .Documento16 pagineGutiérrez, B.A. (2002) .jeisson garcia ospinaNessuna valutazione finora

- Yamaye: Happy Tchocoat DayDocumento12 pagineYamaye: Happy Tchocoat DayAlex Moore-MinottNessuna valutazione finora

- Chocolate: Modern Science Investigates An Ancient MedicineDocumento16 pagineChocolate: Modern Science Investigates An Ancient MedicineTania CastilloNessuna valutazione finora

- Arts of The Ancient Americas: Exhibition ScriptDocumento36 pagineArts of The Ancient Americas: Exhibition ScriptGrendel MictlanNessuna valutazione finora

- The Art of The MayaDocumento8 pagineThe Art of The MayaNicoleta MartinescuNessuna valutazione finora

- Martin 2006 CacaoDocumento30 pagineMartin 2006 CacaoDaniel ShivasNessuna valutazione finora

- Mayan ArtDocumento7 pagineMayan ArtMisael KantunNessuna valutazione finora

- Cocoa (Theobroma Cacao L.) : Theobroma Cacao Also Cacao Tree and Cocoa Tree, Is A Small (4-8 M or 15-26 FT Tall) EvergreenDocumento12 pagineCocoa (Theobroma Cacao L.) : Theobroma Cacao Also Cacao Tree and Cocoa Tree, Is A Small (4-8 M or 15-26 FT Tall) EvergreenApam BenjaminNessuna valutazione finora

- Chocolate Consumption and Cuisine: From Chaco To New MexicoDocumento8 pagineChocolate Consumption and Cuisine: From Chaco To New Mexicosantafesteve100% (1)

- IELTS Reading Practice - 6A - 2 The History of Chocolate - FullDocumento4 pagineIELTS Reading Practice - 6A - 2 The History of Chocolate - FullNguyễn Trang25% (4)

- Blood Water Vomit and Wine Pulque in May PDFDocumento26 pagineBlood Water Vomit and Wine Pulque in May PDFIsus DaviNessuna valutazione finora

- Aztec use of cocoa in early culturesDocumento1 paginaAztec use of cocoa in early culturesaristone marianoNessuna valutazione finora

- Mending The Past: Ix Chel and The Invention of A Modern Pop GoddessDocumento13 pagineMending The Past: Ix Chel and The Invention of A Modern Pop GoddessRocio Garcia ValgañonNessuna valutazione finora

- Her Cup For Sweet Cacao Food in Ancient Maya Society (Traci Ardren) (Z-Library)Documento396 pagineHer Cup For Sweet Cacao Food in Ancient Maya Society (Traci Ardren) (Z-Library)raulNessuna valutazione finora

- Mesquite Pods to Mezcal: 10,000 Years of Oaxacan CuisinesDa EverandMesquite Pods to Mezcal: 10,000 Years of Oaxacan CuisinesVerónica Pérez RodríguezNessuna valutazione finora

- Bray - Et - Al - 2005 Capacocha With Cover Page v2Documento20 pagineBray - Et - Al - 2005 Capacocha With Cover Page v2Luis CaceresNessuna valutazione finora

- Ancient World History 1250 WordDocumento6 pagineAncient World History 1250 Wordapi-487408549Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sarah Loomis Page 1 of 20Documento20 pagineSarah Loomis Page 1 of 20Sarah LoomisNessuna valutazione finora

- Bray Et Al 2005Documento19 pagineBray Et Al 2005Paula VegaNessuna valutazione finora

- La Historia de Chocolate Lesson PlanDocumento4 pagineLa Historia de Chocolate Lesson PlanEmerson NewtonNessuna valutazione finora

- Socha Et Al. 2021 Inca Human Sacrifices From The Ampato and Pichu Pichu Volcanoes PeruDocumento14 pagineSocha Et Al. 2021 Inca Human Sacrifices From The Ampato and Pichu Pichu Volcanoes PeruMarcela SepulvedaNessuna valutazione finora

- Zizumbo Et Al (2009) - Archaeological Evidence of The Cultural Importance of Agave Spp. in Pre-Hispanic ColimaDocumento16 pagineZizumbo Et Al (2009) - Archaeological Evidence of The Cultural Importance of Agave Spp. in Pre-Hispanic ColimaAndres Maria-ramirezNessuna valutazione finora

- The Sacred Bundles and The Coronation oDocumento30 pagineThe Sacred Bundles and The Coronation oNarciso Meneses ElizaldeNessuna valutazione finora

- Nasca Culture and ArtDocumento62 pagineNasca Culture and ArtClinton LeFortNessuna valutazione finora

- НМТ 2023 (пробне) англійськаDocumento1 paginaНМТ 2023 (пробне) англійськаАнна ДомницакNessuna valutazione finora

- Cradles of early Science – Development in MesoamericaDocumento23 pagineCradles of early Science – Development in MesoamericaJohn Mark HerreraNessuna valutazione finora

- Chac The Rain GodDocumento47 pagineChac The Rain GodlzeeNessuna valutazione finora

- Human Sacrifice in South AmericaDocumento9 pagineHuman Sacrifice in South Americaapi-241347855Nessuna valutazione finora

- Mayan culture: Traditions, religion, architecture and moreDocumento12 pagineMayan culture: Traditions, religion, architecture and moreManuel Vasquez NeiraNessuna valutazione finora

- Chocolate: Theobroma CacaoDocumento8 pagineChocolate: Theobroma CacaoManan JainNessuna valutazione finora

- Consumig Interests: Water, Rum and Coca-ColaDocumento20 pagineConsumig Interests: Water, Rum and Coca-ColaDaniel MurilloNessuna valutazione finora

- We Are Still Here: The Taino Heritage of The Greater AntillesDocumento69 pagineWe Are Still Here: The Taino Heritage of The Greater AntillesFranciscoGonzalezNessuna valutazione finora

- Chem Ip Final PDFDocumento25 pagineChem Ip Final PDFBhavadarshiniNessuna valutazione finora

- Azul MayaDocumento14 pagineAzul MayazanthiagoNessuna valutazione finora

- Maya Religion - World History EncyclopediaDocumento9 pagineMaya Religion - World History EncyclopediaDexter OcadoNessuna valutazione finora

- The Development of Cacao Beverages in Formative Mesoamerica 2006Documento16 pagineThe Development of Cacao Beverages in Formative Mesoamerica 2006Lucas BubbaNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 6 Notes WHAPDocumento18 pagineChapter 6 Notes WHAPH15T0RYK1NGNessuna valutazione finora

- Atividade +3ºano III TRiDocumento1 paginaAtividade +3ºano III TRiDeijaninha RibeiroNessuna valutazione finora

- The Ancient Maya PaperDocumento3 pagineThe Ancient Maya Paperapi-250674606Nessuna valutazione finora

- Women's Roles in Pre-Columbian Central and South AmericaDocumento9 pagineWomen's Roles in Pre-Columbian Central and South AmericaOrgonNessuna valutazione finora

- The History of Chocolate (Key)Documento2 pagineThe History of Chocolate (Key)Cuong Huy NguyenNessuna valutazione finora

- Chocolate Is A Preparation of Roasted and Ground: o o o o o o o o o oDocumento9 pagineChocolate Is A Preparation of Roasted and Ground: o o o o o o o o o obhavanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Marcus FigurinesDocumento48 pagineMarcus FigurinesJames Ricardo Zorro MonrroyNessuna valutazione finora

- h1n1 Master TonicDocumento2 pagineh1n1 Master TonicmmetaNessuna valutazione finora

- Order Form for Biorich ProductsDocumento2 pagineOrder Form for Biorich Productsanisilyana bioNessuna valutazione finora

- Homework: I. Find The Word Which Has A Different Sound in The Underlined PartDocumento7 pagineHomework: I. Find The Word Which Has A Different Sound in The Underlined PartTú QuyênNessuna valutazione finora

- 04 Terpenoides CompilationDocumento209 pagine04 Terpenoides Compilationrustyryan77Nessuna valutazione finora

- Automated Young Coconut Scraping and Sorting Machine Through Sequential Minimal OptimizationDocumento12 pagineAutomated Young Coconut Scraping and Sorting Machine Through Sequential Minimal OptimizationBenilda TuanoNessuna valutazione finora

- Matrix of Activities: Schools Division Office of Albay San Antonio National High SchoolDocumento1 paginaMatrix of Activities: Schools Division Office of Albay San Antonio National High SchoolJojie BurceNessuna valutazione finora

- New Connection FormDocumento4 pagineNew Connection Formresufahmed100% (1)

- Substance Abuse StudyDocumento7 pagineSubstance Abuse StudyWXYZ-TV Channel 7 DetroitNessuna valutazione finora

- CH-10 Alcohols, Phenols, EthersDocumento4 pagineCH-10 Alcohols, Phenols, EthersAman YaduvwanshiNessuna valutazione finora

- 7th ClassDocumento13 pagine7th ClassanjuNessuna valutazione finora

- Fast Food Linked to Teen Health RisksDocumento9 pagineFast Food Linked to Teen Health RisksZaff Mat EfronNessuna valutazione finora

- LEARN ABOUT LIFE EXPERIENCES THROUGH TRAVELDocumento3 pagineLEARN ABOUT LIFE EXPERIENCES THROUGH TRAVELValentina VillaniNessuna valutazione finora

- General CVDocumento4 pagineGeneral CVEmma PowerNessuna valutazione finora

- Ethiopia's Coffee Export Trading Special Report - Fiscal Year 2012-2013 - by Alemseged Assefa & Engdashet TsegayeECEAAddis AbabaSeptember 2013Documento29 pagineEthiopia's Coffee Export Trading Special Report - Fiscal Year 2012-2013 - by Alemseged Assefa & Engdashet TsegayeECEAAddis AbabaSeptember 2013poorfarmer100% (2)

- University of Cambridge International Examinations General Certificate of Education Ordinary LevelDocumento4 pagineUniversity of Cambridge International Examinations General Certificate of Education Ordinary Levelmstudy123456Nessuna valutazione finora

- BASF Drug FormulaDocumento56 pagineBASF Drug FormulaabdullahNessuna valutazione finora

- Tjedan XXL Ušteda: Hit Cijena!Documento28 pagineTjedan XXL Ušteda: Hit Cijena!TomeNessuna valutazione finora

- Evaluating Science Experiments for StudentsDocumento201 pagineEvaluating Science Experiments for Studentsobsrvr67% (3)

- Benchmark For RestaurantDocumento16 pagineBenchmark For RestaurantSanchit kanwarNessuna valutazione finora