Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Syarikat Marak Jaya SDN BHD V Syarikat Masin

Caricato da

Zaki ShukorTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Syarikat Marak Jaya SDN BHD V Syarikat Masin

Caricato da

Zaki ShukorCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Page 1

Malayan Law Journal Reports/1991/Volume 2/SYARIKAT MARAK JAYA SDN BHD v SYARIKAT MASINDA

SDN BHD - [1991] 2 MLJ 417 - 23 December 1990

4 pages

[1991] 2 MLJ 417

SYARIKAT MARAK JAYA SDN BHD v SYARIKAT MASINDA SDN BHD

HIGH COURT (IPOH)

PEH SWEE CHIN J

CIVIL SUIT NO 23-32 OF 1986

23 December 1990

Civil Procedure -- Consent order -- Setting aside -- Ground of mistake and fraud -- Order not extracted or

perfected -- Preliminary point raised by defendant -- Defendant argued plaintiff precluded from filing setting

aside application -- Whether court was functus officio -- Whether the order was consent order -- Meaning and

significance of consent order -- Rules of the High Court 1980, O 20 r 11

Civil Procedure -- Order -- Setting aside -- Review of order by court -- Order not perfected -- Rules of the

High Court 1980, O 20 r 11

Words and Phrases -- 'Consent order'

The plaintiff obtained consent judgment which it executed on the same day issuing a prohibitory order in

respect of a large number of pieces of land owned by the defendant. On 9 June 1989, the defendant applied

by 'ex parte summons-in-chambers' that auction or sale of some 73 pieces of land as specified therein be

postponed. The 'ex parte summons-in-chambers' was served on the plaintiff's solicitors on the morning of the

hearing date, and the plaintiff's counsel told the court there that he agreed to the said application. On 24

June 1989 the plaintiff applied to set aside the order dated 9 June 1989 ('order in question') on the ground

that the defendant had misled the plaintiff in that the 'alleged facts' in the supporting affidavit to the

application for the order in question were false and meant to mislead. On the hearing to set aside the order in

question, counsel for the defendant raised a preliminary point to be argued first. The point taken was that the

plaintiff was precluded from filing the application to set aside, and that its remedy was to appeal to the

Supreme Court. He also submitted that the court was functus officio. Counsel for the plaintiff contended that

the order to be set aside was a consent order and since it had not been drawn up and perfected, it could be

set aside on mistake or fraud. Counsel for the defendant argued that it was not a consent order.

Held, dismissing the plaintiff's application:

(1)

(2)

(3)

An order not expressly stated to be a consent order should not be treated as a consent order

and a court would have to be satisfied if it was really one when it was so alleged. The

circumstances of this case indicated a total lack of premeditation of both parties in advance for

a consent order or compromise. Thus, the court found most probably that the order in question

was not a consent order.

Before an order has been perfected, the court has inherent jurisdiction to review the matter.

This power is exercisable whether it is an order made in open court or in chambers, or whether

the order is by consent. When an order is extracted or perfected, the court can still review the

same but only with the consent of both parties, or as expressly provided by the Rules of the

High Court 1980.

As regards the power of reconsidering the order in question, which had not been extracted and

not a consent order, the court was of the view that the nature of this power is not a blanket one;

it is subject to a restriction, which is to correct an error in the order itself where the order made

Page 2

(4)

(5)

does not express the court's manifest intention in the matter or in other words it is not

conformable with such manifest intention of the court. It does not allow a court to make a

fundamentally different order. The power is exercised concurrently with the express power to

correct any clerical error, or any error arising from accidental slip or omission as expressly

conferred by O 20 r 11 of the Rules of the High Court 1980. If such restriction does not exist, it

will somewhat destroy the fabric of the principle that there should be finality in litigation.

The order in question in this instant case that was sought to be set aside on ground of

misapprehension, mistake or fraud and being an unperfected consent order, was certainly not

within the scope of the power to rehear having regard to the grounds stated in the application.

The court therefore exercised its discretion in refusing to rehear and reopen the case relating to

the order in question on the grounds of mistake, misappropriation etc.

The proper remedy would have been the lodging of an appeal within 30 days from the date of

the order in question, ie from 9 June 1989. It was not correct to say that the court was functus

officio when faced with the present application to set aside the order in question, as the order in

question had not yet been perfected, and the court would hear it subject to the restriction

explained above.

Bahasa Malaysia summary

Plaintif telah memperolehi satu penghakiman persetujuan dan melaksanakannya pada hari yang sama

dengan mengeluarkan satu perintah larangan berkenaan beberapa bidang tanah kepunyaan defendan.

Pada 9 Jun 1989, defendan memohon melalui 'saman dalam kamar ex parte' supaya perlelongan atau jualan

73 bidang tanah seperti yang dinyatakan di dalamnya ditangguhkan atas alasan yang ia telah menjumpai 73

orang pembeli bagi 73 buah rumah yang telah didirikan atau akan didirikan di atas 73 bidang tanah itu

'Saman dalam kamar ex parte' itu telah disampaikan kepada peguam plaintif pada pagi hari pembicaraan,

dan peguam plaintif memberitahu mahkamah bahawa beliau bersetuju kepada permohonan itu. Pada 24 Jun

1989 plaintif memohon untuk mengetepikan perintah bertarikh 9 Jun 1989 ('perintah berkenaan') atas alasan

defendan telah mengelirukan plaintif, iaitu 'fakta-fakta yang didakwa' di dalam afidavit sokongan kepada

permohonan untuk perintah berkenaan adalah palsu dan bertujuan membawa kekeliruan. Pada

pembicaraan untuk mengetepikan perintah berkenaan, peguam defendan membangkitkan satu isu

permulaan untuk dihujah terlebih dahulu. Isu itu ialah plaintif ditahan daripada membuat permohonan untuk

mengetepikan, dan remedinya ialah untuk merayu ke Mahkamah Agung. Beliau juga menghujah bahawa

mahkamah adalah functus officio. Peguam plaintif menghujah bahawa perintah yang hendak diketepikan itu

adalah satu perintah persetujuan dan memandangkan yang ia belum digubal dan disempurnakan, ia boleh

diketepikan atas alasan silap atau fraud. Peguam defendan menghujah bahawa ia bukan perintah

persetujuan.

Diputuskan, menolak permohonan plaintif:

(1)

(2)

(3)

Satu perintah yang tidak disebut dengan nyata sebagai perintah persetujuan tidak harus

disifatkan sebagai perintah persetujuan dan mahkamah mesti berpuas hati bahawa ia

sememangnya satu perintah sedemikian apabila dakwaan begitu dibuat. Keadaan kes ini

menunjukkan bahawa keduadua pihak tidak sama sekali memikirkan terlebih dahulu tentang

perintah persetujuan atau kompromi. Jadi, mahkamah mendapati bahawa mungkin sekali

perintah berkenaan bukan satu perintah persetujuan.

1991 2 MLJ 417 at 418

Sebelum satu perintah disempurnakan, mahkamah mempunyai bidang kuasa sedia ada untuk

mengkaji semula perkara itu. Kuasa ini boleh dijalankan sama ada atau tidak perintah itu dibuat

di mahkamah terbuka atau di dalam kamar, atau sama ada perintah itu melalui persetujuan.

Apabila satu perintah dipetik dan disempurnakan, mahkamah masih boleh mengkaji semula

perintah itu tetapi cuma dengan persetujuan kedua-dua pihak, atau seperti diperuntukkan

dengan nyata oleh Kaedah-Kaedah Mahkamah Tinggi 1980.

Berkenaan kuasa mempertimbangkan semula perintah yang disoal di sini, yang belum dipetik

dan bukan satu peritah persetujuan, mahkamah berpandangan yang sifat kuasa ini bukanlah

Page 3

(4)

(5)

secara menyeluruh; ia tertakluk kepada satu had, iaitu untuk membetulkan satu kesilapan

dalam perintah itu sendiri di mana perintah yang dibuat tidak menyatakan tujuan nyata

mahkamah dalam perkara itu, atau dalam perkataan lain, ia tidak mengikut tujuan nyata

mahkamah yang sedemikian. Kuasa itu tidak membenarkan mahkamah membuat satu perintah

yang pada asasnya berlainan. Kuasa itu dijalankan bersama dengan kuasa nyata untuk

membetulkan satu kesilapan kerani, atau apa-apa kesilapan yang berbangkit daripada

kesalahan tak sengaja atau ketinggalan seperti yang diperuntukkan secara nyata oleh A 20 k

11 Kaedah-Kaedah Mahkamah Tinggi 1980. Jika had sedemikian tidak wujud, ia akan

merosakkan prinsip bahawa mestilah ada keputusan muktamad dalam litigasi.

Perintah yang disoal di dalam kes ini yang hendak diketepikan atas alasan kekeliruan, silap

atau fraud dan (bukan satu perintah yang belum disempurnakan), jelas bukan dalam

lingkungan kuasa untuk mendengar semula, berpandukan alasan-alasan yang dinyatakan di

dalam permohonan itu. Mahkamah oleh itu menjalankan budibicaranya dan enggan

mendengar semula atau membuka kembali kes berkenaan perintah yang disoal atas alasan

silap, kekeliruan, dsb.

Remedi yang betul adalah membuat rayuan dalam masa 30 hari dari tarikh perintah itu, iaitu

dari 9 Jun 1989. Adalah tidak betul untuk berkata bahawa mahkamah itu functus officio apabila

berdepan dengan permohonan untuk mengetepikan perintah yang disoal itu, kerana perintah

itu belum disempurnakan dan mahkamah akan mempertimbangkannya tertakluk kepada had

yang diterangkan di atas.

Editorial Note

The plaintiff has appealed to the Supreme Court vide Civil Appeal No 02-405-90.

Cases referred to

Malayan United Finance Bhd v Noormurni Sdn Bhd [1988] 1 MLJ 395 (refd)

SCF Finance v Masri [1987] 1 All ER 194 (refd)

Tan Yew v Seow Fook Meng [1989] 2 MLJ (refd)

Huddersfield Banking Co Ltd v Henry Lister & Son [1895] 2 Ch D 273 (distd)

Jonesco v Beard [1930] AC 298 (refd)

Re Harrison's Shares [1955] Ch D 260 (refd)

Hock Hua Bank Bhd v Sahari bin Murid [1981] 1 MLJ 143 (refd)

Chandless-Chandless v Nicholson [1942] 2 KB 321 (folld)

Re Harrison's Settlement [1955] 1 All ER 185 (refd)

Re St Nazaire Co (1879) 12 Ch D 88 (refd)

Re Thomas [1911] 2 Ch 389 (refd)

Chua Wah Keow v Ng Ho Huat [1961] MLJ 321 (refd)

Ladd v Marshall [1954] 3 All ER 745 (refd)

Holt v Jesse (1876) 3 Ch D 177 (refd)

Hickman v Berens [1895] 2 Ch D 638 (refd)

Page 4

Shepherd v Robinson [1919] 1 KB 474 (refd)

Hatton v Harris [1892] AC 547 (refd)

Tung Lieng (Penang) Trading Co Sdn Bhd v Liew Cheong Thye [1986] 2 MLJ 197 (refd)

Legislation referred to

Rules of the High Court 1980 56 r 2(2)

Ng Seng Lee for the plaintiff.

Azzat Kamaludin for the defendant.

PEH SWEE CHIN J

To cut the story short, the plaintiff obtained consent judgment for a sum of $69,000 with interest and costs.

The plaintiff began to execute the judgment and pursuant to it, a prohibitory order was issued at its behest in

respect of a large number of pieces of land owned by the defendant.

On 9 June 1989, the defendant applied by 'ex parte summons-in-chambers' that auction or sale of some 73

pieces of land as specified therein be postponed on the ground that it had found 73 purchasers in respect of

73 houses built or to be built on 73 pieces of land. For reasons which will become apparent later, it would not

be essential to set out detailed grounds.

Though it started as an 'ex parte summons-in-chambers', it was served on the plaintiff's solicitors. It came up

for hearing before another learned judge in Court 2 and learned counsel for the plaintiff told the court there

that he agreed to the said application. On 9 June 1989 the order was then made.

On 24 June 1989 the plaintiff applied to set aside the order dated 9 June 1989 made earlier (hereafter called

'the order in question') on the ground that the defendant had misled the plaintiff in that the 'alleged facts' in

the supporting affidavit to the application for the order in question were false and meant to mislead.

On the hearing before me to set aside the order in question (in Court 1), learned counsel for the defendant

raised a preliminary point to be argued first, apparently with no objection from the plaintiff. The point taken

was that the plaintiff was precluded from filing the application to set aside, and that its remedy was to appeal

to the Supreme Court. Learned counsel cited Malayan United Finance Bhd v Noormurni Sdn Bhd [1988] 1

MLJ 395 and SCF Finance v Masri [1987] 1 All ER 194. He submitted that the court was functus officio.

Learned counsel further stressed that if the court dismissed his preliminary point, he would ask for an

adjournment to prepare the case on the question of the the merits of the application to set aside the order in

question, which could be heard later.

Learned counsel for the plaintiff submitted that the order to be set aside was a consent order and since it had

not been drawn up and perfected, it could be set

1991 2 MLJ 417 at 419

aside on the grounds of mistake or fraud. He cited Tan Yew v Seow Fook Meng [1989] 2 MLJ -- for the

proposition that a consent order, which was not perfected, could be set aside. He cited Huddersfield Banking

Co Ltd v Henry Lister & Sons [1895] 2 Ch D 273; Jonesco v Beard [1930] AC 298; Re Harrison's Shares

[1955] Ch D 260.

In reply, learned counsel for the defendant informed the court that the colleague who previously handled this

matter in Court 2 when the order in question was made, had said it was not a consent order. Learned

counsel had asked earlier for an adjournment to find out from the said colleague as to whether it was a

consent order. When the hearing resumed on a subsequent day, he so informed the court; a statement from

the Bar table was tendered which the learned counsel for the plaintiff had not raised any objection to.

Page 5

In my view, the crux of the matter was whether the order dated 9 June 1989, and sought to be set aside by

the plaintiff, was a consent order or not. Learned counsel for the plaintiff said it was a consent order, but

learned counsel for the defendant said it was not a consent order based on information supplied by a former

colleague of his who appeared at the hearing in which the order in question was made. When learned

counsel for the defendant informed the court of what he had found out from his colleague of what had

happened, ie it was not a consent order, learned counsel for the plaintiff did not raise the slightest objection

and that could mean in my view, at the very least, that the right to insist on a formal affidavit from that said

previous colleague about what had happened had been waived. Thus, no conclusion could be arrived at

merely on counsel's opposing assertions: the court would have to look further.

In my view, it has been recognized for a long time that there is clear, though subtle distinction, between a

consent order and an order to which the other side or counsel merely submits or offers no objection. The

consequences of a consent order are peculiar to it, eg a consent order cannot be appealed from without

leave; or that a consent order (when perfected) can be set aside in a separate action filed for that purpose:

see Huddersfield Banking Co Ltd v Henry Lister [1895] 2 Ch D 273, and Hock Hua Bank Bhd v Sahari bin

Murid [1981] 1 MLJ 143.

The practice in our courts, if my experience is anything to go by, representative of the general practice,

seems to be that either both parties appear and present a draft of consent order or judgment duly signed by

both asking the court to have it recorded, or both parties have the terms of a consent order dictated to the

court for recording purposes.

The meaning or technical meaning of a consent order was explained with great lucidity by Lord Greene,

Master of Rolls in Chandless-Chandless v Nicholson [1942] 2 KB 321, at p 324, his Lordship said:

The original order which Master Ball made is not on its face expressed to be a consent order, and if it was a consent

order it can only have been by a very regrettable mistake or inadvertance that that circumstance was not expressed in

it. If an order is made by consent the practice should invariably be that it should on the face of it be expressed so to

have been made. When the court finds an order which is not expressed to be made by consent it certainly is not going

to treat it as a consent order unless it is satisfied that it was in fact a consent order. In the present case I am left in

considerable doubt whether this order was a consent order in the strict sense. There is a great deal of difference

between a consent order in the technical sense and an order which embodies provisions to which neither party objects.

The mere fact that one side submits to an order does not make that order a consent order within the technical meaning

of that expression, and I am not the least bit satisfied, having regard to the conflicting statements which we have before

us as to how this order came to be drawn up, that it was a consent order in the technical sense. I cannot help thinking

that at the time he made that order Master Ball cannot have so regarded it, because it is impossible to think that so

learned and experienced a master, when he was making a consent order, should have disregarded what I apprehend

is the universal practice of expressing on the face of the order that it is a consent order.

In my view, from the passage of the learned Master of the Rolls, an order not expressly stated to be a

consent order should not be treated as a consent order and a court would have to be satisfied if it was really

one when it is so alleged.

Reading between the lines in the said passage, the first step would obviously be to give prima facie effect to

the wording of the order itself.

In this case, the order was stated in the minutes of the court file to be a 'PSD', the abbreviation of the Malay

words: 'Perentah seperti dipohon', ie 'Order in terms'. Thus prima facie it was not a consent order. The said

minutes contained the names of both counsel, who appeared at the hearing in which the order in question

was made.

I have obtained a transcript of the notes of proceedings in respect of the prior hearing in which the order was

made, and it is as follows:

CS 23-32-86 (Lampiran 430)

Encik Ng SL mewakili plaintif

Page 6

Encik Anthony Ng mewakili defendan

Peg plaintif:

Peguam defendan telah memfailkan satu permohonan hari ini (lampiran 44). Saya ingin menjawab permohonan

tersebut. Saya pohon penangguhan pendek. Penghakiman telah diambil pada Mei 1986 dan belum mendapat apa-apa

balik.

Peg defendan:

Permohonan saya dibawah O 47 r 7. Penguam plaintif tidak mungkin boleh mendapat menjawab permohonan ini.

Wang dari penjualan akan diberi kepada plaintif.

Peg plaintif:

Kalau wang diberi kepada kita, kami bersetuju.

1991 2 MLJ 417 at 420

Lampiran 44 -- PSD

Lampiran 43 -- Peguam plaintif minta tangguh 2 bulan.

Kepada 25.8.89.

(TT) Dato' Abdul Malek

9.6.89

The circumstances that could also throw some light were that according to learned counsel for plaintiff, on

the morning of the hearing of the summons on which the order in question was made, the summons was

served on him just before the hearing, and after reading the supporting affidavit for the said summons, he

agreed 'to the order in question'. One considered the transcript of the notes of proceedings. These

circumstances indicated a total lack of premeditation of both parties in advance for a consent order or

compromise and most probably, indicated a submission by learned counsel for the plaintiff to the order in

question. The distinct impression the court obtained was the plaintiff had hoped to benefit from the order and

the defendant had found subsequently that such order was financially onerous and was attempting to get rid

of it. Thus, I found most probably that the order in question was not a consent order.

Now, a very significant factor which was not in dispute was that the order in question had never been

extracted and perfected. This factor made a great deal of difference.

In my view, before an order has been perfected, the court has inherent jurisdiction to review the matter.

Please see Re Harrison's Settlement [1955] 1 All ER 185, Re St Nazaire Co (1879) 12 Ch D 88, Re Thomas

[1911] 2 Ch 389 Chua Wah Keow v Ng Ho Huat [1961] MLJ 321. This power is exercisable whether it is an

order made in open court or in chambers, or whether order is by consent; please see Huddersfield Banking

Co Ltd v Henry Lister [1895] 2 Ch D 273, or otherwise so long the order has not been perfected, ie drawn up,

passed and entered. I may just as well mention that when an order is extracted or perfected, the court can

still review the same but only with the consent of both parties, or as expressly provided by the Rules of the

High Court 1980 to give a few examples, in cases of setting aside judgment in default of appearance under

O 13 r 9; setting aside judgment in default of pleadings under O 19 r 9; setting aside judgment in default of

appearance at the hearing under O 14 r 11; or under O 20 r 11 where the order does not correctly set out the

manifest intention of the court. The examples given are only a few of the examples to be found in the Rules

of the High Court 1980.

To revert to the instant case, the order in question had not been extracted or perfected, but as regards the

power of re-considering it, the order in question not being a consent order, what would be actually the nature

of such power to be exercised?

This court was much exercised by this problem. In my view, the nature of this power is not a blanket one; it is

subject to a restriction which is, to correct an error in the order itself where the order made does not express

Page 7

the court's manifest intention in the matter or in other words it is not conformable with such manifest intention

of the court. It does not allow a court to make a fundamentally different order. The power is exercised

concurrently with the express power to correct any clerical error, or any error arising from accidental slip or

omission as expressly conferred by O 20 r 11 of the Rules of the High Court 1980.

In arriving at my view I adopted a passage in Chua Wah Keow [1961] MLJ 321, in which the late Tan Ah Tah

J (as he then was) said at p 322 as follows:

The principle relating to the power of a judge to recall an unperfected order is stated by the English Court of Appeal in

Re Harrison's Settlement [1955] 1 All ER 185 in the following terms (at p 188):

'We think that an order pronounced by the judge can always be withdrawn, or altered or modified by

him until it is drawn up, passed and entered.'

It may perhaps be argued that the principle, laid down as it is in such wide terms, confers upon a judge an unlimited

power to withdraw, or alter, or modify an order made by him which has not yet been perfected. But a perusal of the

cases in which the power has been exercised indicates that the power is not as untrammelled as it appears to be. In all

these cases something transpired between the pronouncement of the order and the perfecting of it which showed that

there was some error in the order as pronounced.

The Court of Appeal in Chua Wah Keow [1961] MLJ 321 held that the trial judge's exercise of the inherent

power in that case was not a correct exercise when the trial court, after dismissing the claim, recalled the

matter (as the order was found not to have been perfected) to allow the plaintiff to amend his statement of

claim and after further argument, gave judgment against the defendant, doing an 'about-turn'. Therefore his

Lordship did not pay mere lip-service when indicating that the power (to recall or re-hear) was not as

untrammelled as it appeared to be. The Court of Appeal there did not think there was any doubt regarding

the corrections of the first order which dismissed the plaintiff's claim with costs.

If such restriction does not exist, it will also somewhat destroy the fabric of the principle that there should be

finality in litigation, for otherwise, the court may decide this way today and it may recall the parties and after

further argument, decide in the opposite way tomorrow as was done in Chua Wah Keow [1961] MLJ 321, this

would somewhat bring some disrepute to the court unless such a radical change is expressly authorized by

any other written law such as follows.

Thus, under O 56 r 2(2) of the Rules of the High Court 1980, from the time of the making of an order in

1991 2 MLJ 417 at 421

chambers by the judge, any party dissatisfied with it may apply to the registrar to have the matter adjourned

into open court for further argument (but without further evidence being allowed except in accordance with

Ladd v Marshall [1954] 3 All ER 745). This, in my view, would represent a continuation of the chambers

proceedings giving an opportunity to parties to present further argument to persuade the judge to come

round to a different decision, including a diametrically opposite decision, on account perhaps of the hurried

nature of chambers proceedings.

Having stated the above matters, in my view, the order in question in this instant case that was sought to be

set aside on ground of misapprehension, mistake or fraud and being an unperfected consent order, was

certainly not within scope of the power to rehear having regard to the grounds stated in the application. I

therefore exercised my discretion in refusing to rehear and reopen the case relating to the order in question

on the grounds of mistake, misapprehension etc.

If however, the order in question had been a consent order which had not been perfected, this would have

been on a different footing altogether and I would not rehear the matter on the ground of mistake etc in order

to decide whether I should withdraw or set aside the order in question as asked as was done in Holt v Jesse

(1876) 3 Ch D 177, Hickman v Berens [1895] 2 Ch D 638, Shepherd v Robinson [1919] 1 KB 474. It was

decided in Huddersfield Banking Co Ltd v Henry Lister [1895] 2 Ch D 273, to the effect that a consent order

can be set aside in a separate action commenced for that purpose on any ground (not necessarily limited to

Page 8

mistake only) that would normally invalidate an agreement such as want of consideration, mistake, fraud,

undue influence etc. In that case, the consent order had been perfected, unlike our instant case, hence a

separate action had to be filed and was filed. In my view, such grounds would also and equally be available

to the plaintiff if the order in question in the instant case was a consent order which had not been drawn up,

passed and entered.

The proper remedy would have been the lodging of an appeal within 30 days from the date of the order in

question, ie from 9 June 1989. It was not correct to say that the court was functus officio when faced with the

present application to set aside the order in question, as the order in question had not yet been perfected,

and the court would hear it subject to the restriction explained above. If the order in question had been

perfected, the court would still not be functus officio, for the court would still have power to amend it by virtue

of the slip rule, ie O 20 r 11 of the Rules of the High Court 1980. There does not seem to be any time limit

under O 20 r 11. In Hatton v Harris [1892] AC 547, Lord MacNaghten said 'Lapse of time has nothing to do

with the matter' when amending and correcting an error in judgment given in 1853 on 27 June 1892.

Just to give another example, an unperfected order was made on 16 December 1910 and amended or

corrected on 24 April 1911, in Re Thomas [1911] 2 Ch 389.

A court only loses all power to amend an order and is functus officio when a judge issues a certificate

requiring no further argument, under O 56 r 2(2) of the Rules of the High Court 1980; please see the decision

of the Supreme Court in Tung Lieng (Penang) Trading Co Sdn Bhd v Liew Cheong Thye [1986] 2 MLJ 197.

In our instant case, no question of such a certificate was involved in connection with the order in question.

I therefore dismissed with costs the application by the plaintiff to set aside the order in question.

Application dismissed.

Solicitors: Yeoh Kian Teik & Co; Chua Brothers Azzat & Xavier.

Reported by Eunice Lee Fei Fong

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Book of Writs - With Sample Writs of Quo Warranto, Habeas Corpus, Mandamus, Certiorari, and ProhibitionDa EverandThe Book of Writs - With Sample Writs of Quo Warranto, Habeas Corpus, Mandamus, Certiorari, and ProhibitionValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (9)

- Heirs of Spouses Reterta Vs MoresDocumento3 pagineHeirs of Spouses Reterta Vs MoresJun Abarca Del RosarioNessuna valutazione finora

- California Supreme Court Petition: S173448 – Denied Without OpinionDa EverandCalifornia Supreme Court Petition: S173448 – Denied Without OpinionValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1)

- Case On Failure To Appear in Preliminaary Case in EjectmentDocumento4 pagineCase On Failure To Appear in Preliminaary Case in EjectmentFulgue JoelNessuna valutazione finora

- HCJD/C-121 Order Sheet for Civil Revision No.1472Documento7 pagineHCJD/C-121 Order Sheet for Civil Revision No.1472zeeshanNessuna valutazione finora

- Almeda Vs CADocumento2 pagineAlmeda Vs CAJessNessuna valutazione finora

- Augusto C. Soliman, Petitioner, vs. Juanito C. FernandezDocumento4 pagineAugusto C. Soliman, Petitioner, vs. Juanito C. FernandezEl G. Se ChengNessuna valutazione finora

- Execution of JudgmentDocumento4 pagineExecution of JudgmentBernard LoloNessuna valutazione finora

- CA upholds dismissal reversal in SMC Pneumatics caseDocumento5 pagineCA upholds dismissal reversal in SMC Pneumatics caseEngelov AngtonivichNessuna valutazione finora

- Jose v. Javellana, G.R. No. 158239, January 25, 2012Documento3 pagineJose v. Javellana, G.R. No. 158239, January 25, 2012Allyza RamirezNessuna valutazione finora

- Boustead TradingDocumento18 pagineBoustead TradingChin Kuen Yei100% (1)

- California vs. Pioneer InsuranceDocumento5 pagineCalifornia vs. Pioneer Insurancechristian villamanteNessuna valutazione finora

- 2 - California & Hawaiian Sugar Co. Vs Pioneer Insurance & Surety CorpDocumento7 pagine2 - California & Hawaiian Sugar Co. Vs Pioneer Insurance & Surety CorpRodolfo Hilado DivinagraciaNessuna valutazione finora

- California & Hawaiian Sugar Co Vs Pioneer Insurance & Surety Corp - 139273 - November 28, 2000 - J. Panganiban - Third DivisionDocumento4 pagineCalifornia & Hawaiian Sugar Co Vs Pioneer Insurance & Surety Corp - 139273 - November 28, 2000 - J. Panganiban - Third DivisionChristian Jade HensonNessuna valutazione finora

- Interlocutory Order and Remedy Against JudgementDocumento8 pagineInterlocutory Order and Remedy Against JudgementMckeenia Wales-CasionanNessuna valutazione finora

- CivilDocumento19 pagineCivilDekwerizNessuna valutazione finora

- JP Latex vs Granger Balloons DisputeDocumento3 pagineJP Latex vs Granger Balloons DisputeCedric EnriquezNessuna valutazione finora

- W Epdw Ukmtq3 D0335B10 Yes: MANU/SC/0257/1963Documento4 pagineW Epdw Ukmtq3 D0335B10 Yes: MANU/SC/0257/1963Angna DewanNessuna valutazione finora

- "Act, 1955") I.E. 'Cruelty'. Summons Were Issued To Respondent SMTDocumento7 pagine"Act, 1955") I.E. 'Cruelty'. Summons Were Issued To Respondent SMTRajeev MishraNessuna valutazione finora

- AUGUSTO C. SOLIMAN vs. JUANITO C. FERNANDEZDocumento4 pagineAUGUSTO C. SOLIMAN vs. JUANITO C. FERNANDEZJei Essa AlmiasNessuna valutazione finora

- Pepsi appeals case on dissolved firmDocumento10 paginePepsi appeals case on dissolved firmdenbar15Nessuna valutazione finora

- Ym VS NabuaDocumento8 pagineYm VS NabuaJesse RazonNessuna valutazione finora

- February 18 2014Documento17 pagineFebruary 18 2014Resci Angelli Rizada-NolascoNessuna valutazione finora

- Jurisprudence ReferenceDocumento20 pagineJurisprudence ReferencePeetsaNessuna valutazione finora

- Remedies On Final and Executory JudgmentDocumento4 pagineRemedies On Final and Executory JudgmentJayson Malero100% (1)

- Dalpat Kumar v. Prahlad SinghDocumento3 pagineDalpat Kumar v. Prahlad Singhdaisy jainNessuna valutazione finora

- Ca VS SoDocumento4 pagineCa VS SoRuel FernandezNessuna valutazione finora

- Thye Hin Enterprise SDN BHD V Daimler Chrysler SDN BHDDocumento8 pagineThye Hin Enterprise SDN BHD V Daimler Chrysler SDN BHDNURSYAZANA AFIQAH MOHD NAZRINessuna valutazione finora

- Soliman V FernandezDocumento5 pagineSoliman V FernandezarnyjulesmichNessuna valutazione finora

- 157 Pascual v. First Consolidated Rural BankDocumento4 pagine157 Pascual v. First Consolidated Rural BankMunchie MichieNessuna valutazione finora

- 19 G.R. No. 139273Documento5 pagine19 G.R. No. 139273JuliaNessuna valutazione finora

- PART 4 Page 721 To 903Documento126 paginePART 4 Page 721 To 903Krishna KanthNessuna valutazione finora

- Lilia T. Ong v. CA October 1991Documento6 pagineLilia T. Ong v. CA October 1991MyrahNessuna valutazione finora

- Davinder Pal Sehgal Indian KanoonDocumento4 pagineDavinder Pal Sehgal Indian Kanoonconsolatamathenge7Nessuna valutazione finora

- RTC Dismisses Appeal in Estate Property DisputeDocumento3 pagineRTC Dismisses Appeal in Estate Property DisputeJoan MagasoNessuna valutazione finora

- BACHRACH CORPORATION Petitioner Vs THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS and PHILIPPINES PORTS AUTHORITY RespondentsDocumento2 pagineBACHRACH CORPORATION Petitioner Vs THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS and PHILIPPINES PORTS AUTHORITY Respondentspaterson M agyaoNessuna valutazione finora

- Malaysian Finance Company Default Judgment Set AsideDocumento12 pagineMalaysian Finance Company Default Judgment Set AsideSeng Wee TohNessuna valutazione finora

- CALIFORNIA AND HAWAIIAN SUGAR COMPANY CASE ON ARBITRATION CLAUSESDocumento6 pagineCALIFORNIA AND HAWAIIAN SUGAR COMPANY CASE ON ARBITRATION CLAUSESJay SuarezNessuna valutazione finora

- Gumabon Versus Larin. G.R. No. 142523. November 27, 2001Documento5 pagineGumabon Versus Larin. G.R. No. 142523. November 27, 2001Sharmen Dizon GalleneroNessuna valutazione finora

- Kiyimba Kaggwa V Katende (Civil Suit No 2109 of 1984) 1985 UGHCCD 1 (23 April 1985)Documento5 pagineKiyimba Kaggwa V Katende (Civil Suit No 2109 of 1984) 1985 UGHCCD 1 (23 April 1985)Makumbi FrancisNessuna valutazione finora

- Pinausukan V Far East BankDocumento5 paginePinausukan V Far East Bankalexis tingNessuna valutazione finora

- CONVERTING REVISION INTO APPEALDocumento3 pagineCONVERTING REVISION INTO APPEALAdv Sohail BhattiNessuna valutazione finora

- Supreme Court Clarifies The Ingredients of Order 1 Rule 10 CPC - Geek Upd8Documento3 pagineSupreme Court Clarifies The Ingredients of Order 1 Rule 10 CPC - Geek Upd8Indrajeet ChavanNessuna valutazione finora

- Lack of due process grounds to annul final judgmentDocumento5 pagineLack of due process grounds to annul final judgmentIvan Montealegre ConchasNessuna valutazione finora

- No Separate Suit Can Be Filed To Ascertain The Validity of A Compromise MemoDocumento11 pagineNo Separate Suit Can Be Filed To Ascertain The Validity of A Compromise MemoLive LawNessuna valutazione finora

- Morkor v. Kuma (1999) Supreme Court RulingDocumento6 pagineMorkor v. Kuma (1999) Supreme Court RulingDAVID SOWAH ADDO100% (1)

- Court Jurisdiction Required for AttachmentDocumento72 pagineCourt Jurisdiction Required for AttachmentMarry SuanNessuna valutazione finora

- In The Lahore High Court Multan Bench, Multan: VersusDocumento12 pagineIn The Lahore High Court Multan Bench, Multan: VersusbeeshortNessuna valutazione finora

- 5 Jose Vs JavellanaDocumento4 pagine5 Jose Vs JavellanaRENGIE GALO100% (2)

- Cathay Pacific Airways Vs Romillo Jr. 141 SCRA 451Documento3 pagineCathay Pacific Airways Vs Romillo Jr. 141 SCRA 451Marianne Shen PetillaNessuna valutazione finora

- Rule 57 Attachment RequirementsDocumento21 pagineRule 57 Attachment RequirementsAlan MakasiarNessuna valutazione finora

- Heirs of Dimaampao v. Alug, G.R. No. 198223, 18 February 2015Documento2 pagineHeirs of Dimaampao v. Alug, G.R. No. 198223, 18 February 2015Aaron James PuasoNessuna valutazione finora

- 135 MC 0029 2021 Matovu and Matovu Advocates V Damani JyotibalaDocumento12 pagine135 MC 0029 2021 Matovu and Matovu Advocates V Damani Jyotibalacommercialcourtroom4Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Golden Country Farms Vs Sanvar Development CorpDocumento2 pagineThe Golden Country Farms Vs Sanvar Development CorpGretel Salley-ObialNessuna valutazione finora

- Arbitration Clause Valid Despite Dispute Over Contract ExistenceDocumento7 pagineArbitration Clause Valid Despite Dispute Over Contract ExistenceHilary MostajoNessuna valutazione finora

- California and Hawaiian Sugar Co. Vs Pioneer InsuranceDocumento5 pagineCalifornia and Hawaiian Sugar Co. Vs Pioneer InsuranceAtty Ed Gibson BelarminoNessuna valutazione finora

- Supreme Court: Nony R. Rivera For Petitioner. Semproniano S. Ochoco For Private RespondentDocumento3 pagineSupreme Court: Nony R. Rivera For Petitioner. Semproniano S. Ochoco For Private RespondentJoselle MarianoNessuna valutazione finora

- Supreme Court of India Page 1 of 6Documento6 pagineSupreme Court of India Page 1 of 6lavidewangan.91Nessuna valutazione finora

- Petitioners Respondents Wenceslao S. Fajardo Romulo M. JubayDocumento11 paginePetitioners Respondents Wenceslao S. Fajardo Romulo M. JubayChingNessuna valutazione finora

- MANU/SC/0715/1991: K. Ramaswamy and G.N. Ray, JJDocumento4 pagineMANU/SC/0715/1991: K. Ramaswamy and G.N. Ray, JJYeshwanth MCNessuna valutazione finora

- Barbara Lim Cheng Sim V Uptown Alliance (M)Documento33 pagineBarbara Lim Cheng Sim V Uptown Alliance (M)Zaki ShukorNessuna valutazione finora

- Malaysia 2Documento22 pagineMalaysia 2Zaki ShukorNessuna valutazione finora

- Civil Law Act 1956Documento38 pagineCivil Law Act 1956Ho Shun MingNessuna valutazione finora

- Can Responsible Government SurviveDocumento15 pagineCan Responsible Government SurviveZaki ShukorNessuna valutazione finora

- Malaysia 2Documento22 pagineMalaysia 2Zaki ShukorNessuna valutazione finora

- Atty disbarment case over worthless checkDocumento211 pagineAtty disbarment case over worthless checkNiñanne Nicole Baring BalbuenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Contempt of CourtDocumento6 pagineContempt of CourtAzarith SofiaNessuna valutazione finora

- A Qualitative Study of Specific Performance Under The Specific Relief Act 1877 of BangladeshDocumento17 pagineA Qualitative Study of Specific Performance Under The Specific Relief Act 1877 of BangladeshNabil Bin SaifNessuna valutazione finora

- Constitutional Law 1 Syllabus (NGP) 2017Documento22 pagineConstitutional Law 1 Syllabus (NGP) 2017Niel Pangan100% (1)

- Sentell v. New Orleans - C. R. Co. - 166 U.S. 698Documento7 pagineSentell v. New Orleans - C. R. Co. - 166 U.S. 698Ash MangueraNessuna valutazione finora

- State's MTS Case Law2Documento90 pagineState's MTS Case Law2JM MillerNessuna valutazione finora

- Mukesh Kalu Ram Revision Petition by AshtoshDocumento20 pagineMukesh Kalu Ram Revision Petition by AshtoshBrahm KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Heirs of Mesina Vs Heirs of FianDocumento7 pagineHeirs of Mesina Vs Heirs of FianReena MaNessuna valutazione finora

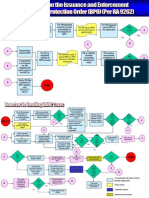

- BPO FlowchartDocumento2 pagineBPO Flowchartnhaeizy100% (14)

- Lim VSDocumento6 pagineLim VSLoveAnneNessuna valutazione finora

- CONSTI Syllabus Atty. JamonDocumento9 pagineCONSTI Syllabus Atty. JamonChedeng KumaNessuna valutazione finora

- Judge accused of improper bail grantDocumento9 pagineJudge accused of improper bail grantXXXNessuna valutazione finora

- SNYDER v. MILLERSVILLE UNIVERSITY Et Al - Document No. 19Documento60 pagineSNYDER v. MILLERSVILLE UNIVERSITY Et Al - Document No. 19Justia.comNessuna valutazione finora

- Juego-Sakai vs. Republic DigestDocumento2 pagineJuego-Sakai vs. Republic DigestEmir Mendoza100% (3)

- (PC) R. Rhodes v. A.A. LaMarque, Warden, Et Al. - Document No. 1Documento3 pagine(PC) R. Rhodes v. A.A. LaMarque, Warden, Et Al. - Document No. 1Justia.comNessuna valutazione finora

- District Court Forms ManualDocumento131 pagineDistrict Court Forms ManualWayneSchneberger100% (1)

- Gov Uscourts Nysd 518649 6 0Documento16 pagineGov Uscourts Nysd 518649 6 0CNBC.com0% (1)

- Deo C. Choudhury v. Polytechnic Institute of New York, 735 F.2d 38, 2d Cir. (1984)Documento10 pagineDeo C. Choudhury v. Polytechnic Institute of New York, 735 F.2d 38, 2d Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Misamis Oriental Association of Coco Traders, Inc. vs. Department of Finance SecretaryDocumento10 pagineMisamis Oriental Association of Coco Traders, Inc. vs. Department of Finance SecretaryXtine CampuPotNessuna valutazione finora

- Administrative Law Case Digests: Powers and Functions of Administrative AgenciesDocumento8 pagineAdministrative Law Case Digests: Powers and Functions of Administrative AgenciesAizaFerrerEbina100% (1)

- Supreme Court OrderDocumento74 pagineSupreme Court OrderHNNNessuna valutazione finora

- Diego V Castillo DigestDocumento1 paginaDiego V Castillo DigestArgel Joseph CosmeNessuna valutazione finora

- SC upholds constitutionality of agrarian reform lawsDocumento137 pagineSC upholds constitutionality of agrarian reform lawsLouiseNessuna valutazione finora

- Imerman FinalDocumento49 pagineImerman FinalThe GuardianNessuna valutazione finora

- United States v. Obed Hoyte, United States of America v. Anif Christopher Williams, United States of America v. Kenton Omar Perrin, United States of America v. Kenton Omar Perrin, 51 F.3d 1239, 4th Cir. (1995)Documento10 pagineUnited States v. Obed Hoyte, United States of America v. Anif Christopher Williams, United States of America v. Kenton Omar Perrin, United States of America v. Kenton Omar Perrin, 51 F.3d 1239, 4th Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- US vs. SerapioDocumento2 pagineUS vs. SerapioanalynNessuna valutazione finora

- Automax v. Zurich, 10th Cir. (2013)Documento25 pagineAutomax v. Zurich, 10th Cir. (2013)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Documento27 pagineUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNessuna valutazione finora

- Land Titles and DeedsDocumento100 pagineLand Titles and DeedsGe LatoNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 1: Business and Its Legal EnvironmentDocumento4 pagineChapter 1: Business and Its Legal EnvironmentkhaseNessuna valutazione finora