Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

2005.. The Anger Management Pro PDF

Caricato da

HanaeeyemanDescrizione originale:

Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

2005.. The Anger Management Pro PDF

Caricato da

HanaeeyemanCopyright:

Formati disponibili

This article was downloaded by: [Nanyang Technological University]

On: 17 June 2014, At: 14:07

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House,

37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cjid20

The Anger Management Project: A group intervention

for anger in people with physical and multiple

disabilities

a

Nick Hagiliassis , Hrepsime Gulbenkoglu , Mark Di Marco , Suzanne Young & Alan Hudson

a

Scope, Victoria, Australia

RMIT University, Victoria, Australia

Published online: 15 Jan 2014.

To cite this article: Nick Hagiliassis, Hrepsime Gulbenkoglu, Mark Di Marco, Suzanne Young & Alan Hudson (2005) The Anger

Management Project: A group intervention for anger in people with physical and multiple disabilities, Journal of Intellectual

and Developmental Disability, 30:2, 86-96

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13668250500124950

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the Content) contained

in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no

representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the

Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and

are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and

should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for

any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever

or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of

the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic

reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any

form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://

www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, June 2005; 30(2): 8696

The Anger Management Project: A group intervention for anger in

people with physical and multiple disabilities

NICK HAGILIASSIS1, HREPSIME GULBENKOGLU1, MARK DI MARCO1,

SUZANNE YOUNG1 & ALAN HUDSON2

Scope, Victoria, Australia, 2RMIT University, Victoria, Australia

Downloaded by [Nanyang Technological University] at 14:07 17 June 2014

Abstract

Background This paper describes the evaluation of a group program designed specifically to meet the anger management

needs of a group of individuals with various levels of intellectual disability and/or complex communication needs.

Method Twenty-nine individuals were randomly assigned to an intervention group or a waiting-list comparison group. The

intervention comprised a 12-week anger management program, based on Novacos (1975) cognitive-behavioural

conceptualisation of anger, which incorporates adapted content and pictographic materials developed for clients with a

range of disabilities.

Results On completion of the program, clients from the intervention group had made significant improvements in their selfreported anger levels, compared with clients from the comparison group, and relative to their own pre-intervention scores.

Treatment effects were maintained at 4-month follow-up. In contrast, there was an absence of measured improvements in

quality of life.

Conclusions The results provide evidence for the programs effectiveness as an intervention for anger problems for

individuals with a range of disabilities.

Introduction

Anger is defined as a state of emotion that involves

varying intensities of feelings from aggravation and

annoyance to rage and fury (Spielberger, 1991).

Although anger is a normal emotion, it can become

problematic if it is expressed inappropriately, or if it

is experienced in excessive, intensive, or prolonged

forms, and if it results in impairment in personal

functioning. Poor anger control has been shown to

be an important determinant of aggressive and other

forms of challenging behaviour for people with an

intellectual disability (Black, Cullen, & Novaco,

1997; Kiernan, 1991). Anger expressed through

aggression can result in obvious negative outcomes

for the individual with a disability (e.g., restricted

opportunities, impaired social relationships, diminished self-esteem). The behavioural consequences of

anger can also present as a burden to families and

staff working in day and residential services, as well

as to the wider community. Even anger that is not

expressed through aggression, but rather through

passive means (e.g., insults, complaints, sarcasm,

intimidation), can have detrimental consequences

for the individual and others.

While prevalence rates for anger control problems

in people with a disability compared with people

without a disability are not firmly established, there

is evidence that people with disabilities present with

higher rates of anger control problems compared

with people without disabilities (Hill & Bruininks,

1984; Sigafoos, Elkins, Kerr, & Attwood, 1994;

Smith, Branford, Collacott, Cooper, & McGrother,

1996; Taylor, Novaco, Gillmer, & Thorne, 2002).

In establishing prevalence rates, researchers have

tended to examine rates of aggressive behaviour,

which is often mediated by anger (Taylor, 2002;

Taylor et al., 2002). In a survey of 2,277 people with

intellectual disability, Smith et al. (1996) observed

that 23% of males and 19% of females were reported

by carers as being physically aggressive, while in

another survey of 2,412 people, Sigafoos et al.

(1994) found 11% of the total population were

identified by service providers as exhibiting aggressive behaviour.

Having recognised that anger can present as a

significant problem for some people with disabilities,

practitioners have endeavoured to develop specialised anger management interventions for this

population. The few programs developed to date

Correspondence: Dr Nick Hagiliassis, Psychology Advisor, Scope, 177 Glenroy Road, Glenroy, Victoria 3046, Australia. E-mail: nhagiliassis@scopevic.org.au

ISSN 1366-8250 print/ISSN 1469-9532 online # 2005 Australasian Society for the Study of Intellectual Disability Inc.

DOI: 10.1080/13668250500124950

Downloaded by [Nanyang Technological University] at 14:07 17 June 2014

The Anger Management Project

(e.g., Benson, 1992; Gilmour, 1998; Howells,

Rogers, & Wilcock, 2000) have tended to adopt

approaches to intervention based on the seminal

work of Novaco (1975, 1986). Consistent with the

cognitive-behavioural view, Novaco argues that it is

an individuals appraisal of an event or situation that

mediates their emotional arousal and behavioural

response, and that determines whether or not they

are likely to feel angry and/or behave aggressively.

One of the foremost programs of this type is

Bensons (1992) Anger Management Training Program. In line with Novacos cognitive-behavioural

model of anger, Bensons program focuses on

self-instructional training, relaxation training, and

training in problem-solving skills.

One feature of programs such as that of Benson

(1992) is that they are generally targeted at

individuals with mild to moderate degrees of

intellectual disability. Adaptation of these methods

is needed for people whose cognitive limitations are

more severe in nature. Moreover, such programs are

not easily accessible to people with severe communication impairment, in particular those with expressive language difficulties. The heavy emphasis on the

need to contribute to group processes using varying

levels of verbal ability can be a barrier for people who

use nonverbal or augmentative communication

approaches. At a more extreme level, a feature of

some anger management programs has been the

screening out of prospective clients for group-based

anger management interventions on the basis that

they have difficulties in verbal communication,

particularly in terms of labelling feelings and emotions (Howells et al., 2000). Clearly, there is a

pressing need for anger management tools that are

tailored to the needs of people with various levels of

cognitive ability, but that are also more inclusive of

individuals with various degrees of verbal ability.

Additionally, there is a paucity of research on the

effectiveness of group programs for anger control

problems for people with cognitive disabilities.

There have been at least two evaluations of

Bensons (1992) program. The program was evaluated by Benson, Johnson Rice, and Miranti (1986),

who found that anger management training for 54

adults with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities

using a group format was associated with positive change on a variety of measures, including

self-reports and carers ratings of aggressive behaviour. In an attempt to replicate the findings of

Benson et al., King, Lancaster, Wynne, Nettleton,

and Davis (1999) evaluated the efficacy of the

Benson program with 11 adults with mild intellectual disabilities using a group format. Improvements

were evident on a range of measures of anger and

87

self-esteem. However, a limitation of both the King

et al. study and the Benson et al. study is the absence

of a comparison group; consequently, neither could

be confident that the effects were as a result of the

intervention. This is acknowledged by both groups

of researchers, with King et al. stating that a

direction for future research is for more controlled

investigations.

Gilmour (1998) reports the qualitative findings of

a pilot anger management program for 10 clients

presenting with mild to moderate intellectual

disability and challenging behaviours. Following

participation in a 14-week program that included

components on personal anger triggers, coping

strategies, assertiveness and communicatory confidence, client gain was noted through increases in the

use of communication, self-advocacy and assertiveness, and reductions in the severity and frequency of

challenging behaviours. However, although the

study provides initial qualitative evidence for the

effectiveness of this approach to challenging behaviour, the small sample size, the absence of a nontreatment group and the fact that no quantitative

results were reported mean that these data need to

be interpreted cautiously.

Howells et al. (2000) describe a 12-session program for 5 clients with mild to moderate intellectual

disabilities referred to a psychology clinic for

difficulties with aggression. The program covered a

range of topics, including the recognition of feelings,

identifying the physical and psychological signs of

anger, personal anger triggers, alternative thoughts

and attributions of the actions of others, and

teaching functional alternatives to aggression.

Although the authors attempted to include a number

of outcome measures (e.g., a self-esteem rating

scale) there was a lack of robust quantitative data

to indicate any potential effects of the training, a

limitation acknowledged by the authors themselves.

However, qualitative data collected through semistructured interviews indicated that all participants

felt more in control of their own anger on completion of the program.

Acknowledging the need for the development of

anger management programs for people with more

severe disabilities, Rossiter, Hunnisett, and Pulsford

(1998) developed a program targeted primarily

at people with moderate to severe intellectual

disabilities. This program incorporated elements

from Bensons (1992) program, but with a further

modified structure to tailor it to the needs of people

with more limited verbal ability and cognitive

capacity. Six people with moderate to severe

intellectual disabilities participated in 8 training

sessions. Based on qualitative data, the group

Downloaded by [Nanyang Technological University] at 14:07 17 June 2014

88

N. Hagiliassis et al.

appeared to demonstrate that people with moderate

to severe intellectual disabilities are able to make use

of a simplified approach to anger management.

However, although the data were suggestive of

positive effects, the authors acknowledged that the

study was not subject to any kind of control, while

participants continued to receive additional individualised input (e.g., psychological), and there were

no robust data to objectively quantify reductions in

anger responses.

There are few treatment studies involving comparison groups with clients with intellectual disabilities. Rose, West, and Clifford (2000) examined a

group treatment program for individuals with mild

to moderate intellectual disabilities, comparing these

individuals to a similar group of individuals waiting

to participate. The program was similar to Rose

(1996), which used a modified Novaco approach,

but with additional individualised techniques. Five

groups were held over 2 years for between 6 and

9 participants, with a total of 25 people in the

intervention groups. Nineteen people participated in

a waiting-list control group, a significant number of

whom went on to participate in subsequent intervention groups. Measures administered included an

anger inventory and a depression inventory.

A reduction in measured levels of anger and

depression occurred after group treatment, with

treatment effects maintained at 6- and 12-month

follow-up. While this controlled study demonstrated significant reductions in expressed anger for

subjects receiving anger management training, a

limitation of this study is that it occurred without

randomisation.

Perhaps the most robustly conducted study to

date in this area emerges from Willner, Jones,

Tams, and Green (2002). In their randomised

controlled trial, 14 people with intellectual disabilities with anger management difficulties were

assigned to a treatment group and waiting-list

comparison group, with the treatment group participating in 9 sessions of a cognitive-behaviouralbased anger management program. The program

included content relating to the triggers that evoke

anger, physiological and behavioural components of

anger, behavioural and cognitive strategies to avoid

the build-up of anger and for coping with angerevoking situations, and acceptable ways of expressing anger. The intervention was evaluated by

means of two anger inventories, which were

completed by both clients and carers. Individuals

in the treatment group improved on both self- and

carer-ratings, relative to their own pre-intervention

scores, and to the comparison group post-intervention. Of note, the degree of improvement was

strongly correlated with IQ. However, although this

study is perhaps the first randomised controlled trial

comparing treatment and non-treatment groups, the

extent to which the results may be generalised is

limited because of the small numbers involved

(N 5 14). Additionally, beyond reporting that all

clients experienced mild intellectual disabilities,

there is little information given about other client

characteristics, such as primary communication

mode (e.g., verbal/nonverbal). A final limitation is

that detail of the programs plan and content is not

presented, making it difficult for other researchers

and practitioners to replicate.

Purpose of the study

The review of the literature demonstrates that while

there have been some attempts to develop programs

for individuals with disabilities with anger management problems, there are few such programs to date.

Of the few developed, most are targeted at

individuals with mild to moderate intellectual disability, and with various levels of verbal ability.

There is clearly a need to develop anger management programs that are accessible to a wider range of

individuals with disabilities, and specifically, those

with more limited cognitive skills and/or more

complex communication needs. Perhaps the

only study to focus on people with more severe

intellectual disabilities is that of Rossiter et al.

(1998), but this study was not subject to rigorous

evaluation.

Another issue is the overall lack of robust data on

the effectiveness of group anger management

programs for individuals with disabilities. Many

studies suffer from methodological problems, such

as the absence of comparison groups, the use of

small samples, and the lack of reliable, quantitative

data, that makes consolidation and interpretation of

findings difficult. Willner et al. (2002) provide

perhaps the first randomised controlled trial of an

anger management intervention in individuals with

intellectual disabilities. However, their study

involved only small numbers of participants, while

the population under investigation was individuals

with mild intellectual disabilities.

Following on from these issues, the present study

examines the effectiveness of a 12-session anger

management program (Gulbenkoglu & Hagiliassis,

2002) for individuals with a range of levels

of

intellectual

disability

and/or

complex

communication needs. The programs effectiveness

was evaluated using a randomised controlled trial of

29 individuals with disabilities with anger control

difficulties.

89

The Anger Management Project

Method

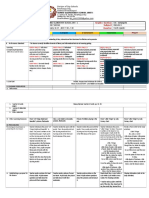

Table 1. Client characteristics

Downloaded by [Nanyang Technological University] at 14:07 17 June 2014

Participants

Following ethics approval, all individuals involved

in the project were recruited from Scope.1 A flier

was distributed seeking expressions of interest, from

which 34 referrals were received. An initial interview with a psychologist involved with the project

was conducted to confirm that an individual was

presenting with a clinically significant anger problem and that they would engage in and benefit

from involvement in a group program. Four

referrals were deemed unsuitable. In two cases,

this was because the presenting issue was not

assessed as being a core problem in anger control,

while in the other two cases, the individuals

ultimately had reservations about participation in

a group and expressed a preference for individualised treatment. A referral to individualised anger

management counselling was arranged in these

circumstances.

Clients were based either in the North West (NW)

or South East (SE) Melbourne Metropolitan

Region. It was therefore decided to establish two

intervention groups, one in each of these regions, to

be delivered simultaneously. The 30 clients were

allocated randomly to an immediate intervention

group or a waiting-list comparison group, using

regional locality as a stratification variable. Within

each region, clients were assigned by simple random

allocation to an intervention group or a comparison

group, with males and females allocated alternately

to ensure an even spread of gender. An individual

who was not involved in the study and who was

blinded to the identity of the clients performed the

randomisation. For the NW region, the intervention

and comparison groups were assigned 7 participants

each, while for the SE region, each group was

assigned 8 participants. It eventuated that one client

in the SE intervention group withdrew from the

study (citing difficulties with transportation, as well

as reduced motivation for participation in the group,

as a reason), resulting in 7 members in that

intervention group as well. Hence, the data of 29

individuals were retained. Note that although

individuals in the comparison group did not receive

the intervention, they continued to have access to

their existing level of support (ranging from no

formal support to individual counselling).

Client characteristics are presented in Table 1. Of

note, a number of clients who used a means other

than speech as their primary form of communication were included in the study. These clients

employed a range of nonverbal communication

methods, including electronic communication

Intervention

(n 5 14)

Characteristic

Male

Female

No intellectual

disabilitya

Borderline intellectual

disabilityb

Mild intellectual

disabilityc

Moderate intellectual

disabilityd

Severe intellectual

disabilitye

Cerebral palsy

Visual disability

Psychiatric disability

Verbal

communication

Nonverbal

communication

Uses wheelchair

Ambulant

Comparison

(n 5 15)

Number Percentage Number Percentage

7

7

0

50%

50%

0%

9

6

1

60%

40%

7%

36%

13%

7%

7%

29%

27%

29%

47%

14

1

0

10

100%

7%

0%

71%

14

2

1

11

93%

14%

7%

73%

29%

27%

10

4

71%

29%

9

6

60%

40%

a

PPVT-III Standard Score .80, bPPVT-III Standard Score

7180, cPPVT-III Standard Score 6170, dPPVT-III Standard

Score 5160, ePPVT-III Standard Score ,51.

devices, communication boards, as well as sign,

gesture and facial expressions.

Assessments

Four weeks prior to the commencement of the

program, clients were administered Section A of the

Novaco Anger Scale (NAS: Novaco, 1994) designed

to measure the cognitive, arousal and behavioural

aspects of anger. The NAS has been found to have a

high internal (.95) and testretest (.88) reliability as

well as sound validity (Novaco, 1994). There were

48 questions in total. Participants responded along a

3-point scale (1 5 yes, 2 5 sometimes, 3 5 no) reflecting their level of agreement, with a minimum

possible score of 48 and a maximum of 144.

Participants provided their responses verbally, or

by pointing to a pictograph for yes, no or sometimes.

Minor modifications were made to some of the

items, so as to be more appropriate to a group of

clients with physical disabilities (e.g., adapting the

item I walk around in a bad mood to I move around in a

bad mood), while maintaining the integrity of the

meaning of the original item.

Clients were also administered the Outcome Rating

Scale (ORS: Miller & Duncan, 2000), designed to

measure change in a persons quality of life as a

result of a therapeutic intervention. Participants

Downloaded by [Nanyang Technological University] at 14:07 17 June 2014

90

N. Hagiliassis et al.

were asked four questions: How do you feel about life

overall? How do you feel about yourself ? How do you feel

about your family and friends? and How do you feel

about your day service/workplace? Minor modifications

were made to the original ORS questions so as to be

more contextually relevant to the client group under

investigation in the present study. For each question,

participants rated themselves using a simple 5-point

visual scale (1 5 really bad, 2 5 bad, 3 5 OK,

4 5 good, 5 5 really good), with a minimum possible

score of 5 and maximum of 20. Because the ORS

requires only a simple pointing response, it offers

some promise for the measurement of quality of life

in people with disabilities, and hence was selected

for use in the present study.

Clients were generally able to respond to the NAS

and ORS assessments adequately. For the few items

that clients were uncertain of (e.g., when items

tapped domains of life they had not experienced),

these items were excluded from the scoring and a

pro-rated total score was calculated. The NAS and

ORS assessments were also administered postintervention, and at a 4-month follow-up assessment. Of note, blind assessment at each of these

time points could not be achieved. In an attempt to

attenuate this issue, client assessments were conducted by a psychologist who was not a facilitator for

the group the client attended, and by assessors who

did not have an ongoing professional relationship

with or detailed knowledge of the client.

Finally, clients were administered the Peabody

Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT-III: Dunn &

Dunn, 1997) and the Ravens Coloured Progressive

Matrices (CPM: Raven, Raven, & Court, 1998) as a

measure of receptive vocabulary and nonverbal

reasoning abilities respectively. Both the PPVT-III

and CPM have particular utility as assessment

tools for individuals with complex communication needs because they do not require a verbal

response.

The intervention

The intervention delivered was The Anger

Management Training Package (Gulbenkoglu &

Hagiliassis, 2002), a new anger management package designed for individuals with a range of levels of

intellectual disability and/or complex communication needs. The program is also developed to reflect

themes and content relevant to the lives of people

with physical disabilities, and incorporates adapted

activities and techniques (e.g., modified relaxation)

for this group.

The theoretical framework adopted in the package

draws on Novacos (1975) cognitive-behavioural

conceptualisation of anger, which has also been

utilised in other programs (e.g., Benson, 1992).

Physiological components of anger are addressed

through training in the use of relaxation techniques

(e.g., progressive muscle relaxation, visualisation,

deep breathing), but using modified procedures for

people whose physical abilities, verbal abilities and

capacity for understanding complex concepts are

compromised. The cognitive components of anger

are addressed through cognitive restructuring.

Although cognitive restructuring has been an intrinsic feature of various anger management packages

for people with intellectual disabilities (e.g., Benson,

1992; Taylor et al., 2002; Rossiter, et al., 1998), the

extent to which clients with limitations in cognition

can benefit from such an approach is not clear.

Taylor et al. (2002) and others (Rose, 1996; Rose

et al., 2000; Whitaker, 2001) suggest that the

cognitive components of anger interventions may

have limited efficacy in clients with intellectual

disabilities, while non-cognitive components (e.g.,

relaxation) may have greater benefit. Nevertheless,

given the central role of cognition as a mediator of

anger, a cognitive restructuring component could

not have been ignored. Similar to Bensons (1992)

program, training in self-instruction is included, with

the aim being to increase the use of calm thoughts

and reduce angry thoughts. The behavioural

components of anger are addressed through

problem-solving and assertiveness skills training. A

standard four-step problem-solving model was used,

that involved (a) defining the problem, (b) looking

for possible solutions, (c) implementing the solution

most likely to prove effective, and (d) evaluating the

success of that solution (King et al., 1999; Rose et al.,

2000). A standard model for teaching assertiveness

training was used, that included (a) identifying

personal rights and responsibilities, (b) describing

nonassertive behaviour and its consequences, and

(c) exploring the positive consequences of behaving

assertively (Holbrook Freeman & Freeman Adams,

1999).

A prominent feature of the package is an emphasis

on pictographic symbols, functioning as a visual

learning aid for clients with cognitive limitations, as

well as an augmentative communication medium for

clients with complex communication needs. The

importance of pictographs as an adjunct to learning

is highlighted by Turk and Francis (1990), who

found that information presented to individuals with

intellectual disabilities in the form of instruction

without any accompanying visual aids was rapidly

forgotten. Similarly, active learning techniques, roleplay and repetition were emphasised to facilitate

skills acquisition.

Downloaded by [Nanyang Technological University] at 14:07 17 June 2014

The Anger Management Project

The program comprises 12 weekly sessions of 2

hours duration, including a 15-minute break. Each

session is fully scripted and follows a standard

format, beginning with a review of skills learned

during the previous session, followed by an introduction and explanation of the major session topic

and then addressing the key learning aims for that

session. The key elements of the content of the 12

anger management group sessions are presented in

Table 2.

As two intervention groups were conducted in the

present study, slight variations in focus, pace and

emphasis may have occurred across the two groups,

given the realities of working with different groups

of participants. However, this was not felt to be a

significant issue and was attenuated by the standardised nature of the package. Sessions were facilitated

by two psychologists, a male and a female in the case

of the NW intervention group, and the same female,

along with another female, in the case of the SE

intervention group. Two carers attended the SE

intervention group, and they were encouraged to

91

participate in that group, and to support clients

other than their own with activities and role-plays. A

total of 11 out of the 14 clients in the intervention

groups attended all 12 sessions, while two clients

attended 11 sessions, and one client attended 10.

Results

PPVT-III, CPM and age data are presented in

Table 3. Univariate analyses of variance revealed

there were no significant differences between the

intervention groups (n 5 14) and comparison groups

(n 5 15) on PPVT-III and CPM measures, or on

age. Of note, these data indicate that both the

intervention and comparison groups were inclusive

of individuals with a range of cognitive abilities.

Although not directly equivalent to IQ, performances on these assessments suggest the sample

was inclusive not only of people with mild intellectual disabilities, but also those with moderate to

severe intellectual disabilities. PPVT-III standard

scores ranged from 40 to 79 for the intervention

Table 2. Content of the 12 anger management group sessions

Session

Topic

Key learning objectives

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

Introduction to anger management

Introduction to anger management

Learning about feelings and anger

Learning about helpful and unhelpful ways

Learning to relax

Learning to relax

Learning to think calmly

Learning to think calmly

Learning to think calmly

10

Learning to handle problems

11

Learning to speak up for ourselves

N

N

N

12

Putting it all together

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

introduce participants and conduct ice-breaker exercise

present rules of group work

introduce concept of anger and anger management

further explore concept of anger and anger management

conduct brief self-assessment of anger

present an overview of material to be covered in program

identify and label common feelings

examine triggers that evoke anger

explore the cognitive, physiological and emotional correlates of anger

distinguish between helpful (adaptive) and unhelpful (maladaptive) coping

strategies

have participants identify their own helpful and unhelpful coping strategies

introduce concept of relaxation and its role in anger management

conduct a range of four modified relaxation techniques: deep breathing, selfaffirmation, visualisation and slow-counting

conduct a modified progressive muscle relaxation technique

explore lifestyle changes to enhance relaxation

examine the difference between calm thoughts and angry thoughts

explore the role of angry thoughts in mediating feelings and behaviour

introduce concept of self-coping statements

develop individualised self-coping statements

examine common thinking errors

explore other healthy thinking strategies

explore a range of problems experienced and how these impact on anger

introduce a four-step problem-solving framework

have participants apply problem-solving framework to a recent problem

experienced

examine the difference between passive, aggressive and assertive behaviours

explore a range of practical techniques for assertive behaviour

have participants identify assertive behaviours for a recent anger-evoking

situation

have participants develop their own personal anger management plan

complete individualised evaluation

92

N. Hagiliassis et al.

Table 3. Age, PPVT-III and CPM data for intervention and comparison groups

Intervention (n 5 14)

Age (years)

PPVT-III (standard score)

CPM (age-equivalent score)

Mean

SD

Min.

Max.

Mean

SD

Min.

Max.

44.93

60.00

6.89

13.04

14.25

1.80

28

40

5

74

79

11

43.57

56.77

7.31

12.76

18.11

2.48

26

40

5

73

97

12

groups and 40 to 97 for the comparison groups.

CPM age-equivalent scores ranged from 5 to 11

years in the intervention groups and 5 to 12 years in

the comparison groups.

Downloaded by [Nanyang Technological University] at 14:07 17 June 2014

Comparison (n 5 15)

Novaco Anger Scale (NAS) results

The overall NAS data are presented in Fig. 1. Note

that an increase in mean NAS scores is associated

with an increase in anger control. A repeated

measures ANOVA with NAS scores as the dependent measure reveals a non-significant main effect

for treatment condition (intervention group, comparison group), a significant main effect for time

of assessment (pre-intervention, post-intervention,

4-month follow-up), F(2,26) 5 5.31, p,.05, and

a significant treatment condition 6 time of assessment interaction effect, F(2,26) 5 4.87, p,.05.

Closer inspection of this interaction effect reveals

that there was no significant difference between the

mean NAS scores of the intervention groups

(M 5 80.79, SD 5 18.04) and comparison groups

Figure 1. NAS data for intervention and comparison groups.

(M 5 80.01, SD 5 22.02) at pre-intervention.

At post-intervention, individuals from the intervention groups had achieved a higher NAS score

on average (M 5 97.36, SD 5 21.27) compared

with individuals from the comparison groups

(M 5 81.13, SD 5 18.85), a statistically significant

difference, t(27) 5 2.18, p,.05. A statistically

significant difference was maintained between the

intervention groups (M 5 100.86, SD 5 24.47) and

comparison groups (M 5 80.33, SD 5 20.10) at

4-month follow-up, t(27) 5 2.48, p,.05.

Within the intervention groups, there was an

increase in the mean NAS scores from 80.79

(SD 5 18.04) at pre-intervention, to 97.36

(SD 5 21.27) at post-intervention, a statistically

significant result, t(13) 5 3.34, p,.01. The difference in mean NAS scores between pre-intervention

and 4-month follow-up (M 5 100.86, SD 5 24.47)

was also statistically significant, t(13) 5 3.80, p,.01.

NAS scores at post-intervention and at 4-month

follow-up did not differ significantly for the intervention groups. In contrast, the NAS scores for the

The Anger Management Project

Downloaded by [Nanyang Technological University] at 14:07 17 June 2014

comparison groups over the same time periods

remained relatively stable, from 80.01 (SD 5

22.02) at pre-intervention, to 81.13 (SD 5 18.85)

at post-intervention and 80.33 (SD 5 20.10)

at 4-month follow-up, with none of these differences proving significant. Collectively, these results

indicate an improvement in anger control as a

result of participation in the intervention groups.

Clients in the intervention group improved relative

to the comparison group at post-intervention, and

relative to their own pre-intervention scores, with

these improvements maintained at 4-month followup.

Outcome Rating Scale (ORS) results

The ORS data are presented in Fig. 2. A repeated

measures ANOVA with ORS scores as the dependent measure reveals a non-significant main effect

for both treatment condition and time of assessment,

as well as a non-significant treatment condition 6

time of assessment interaction effect. Although

individuals from the intervention groups had slightly

higher ORS mean scores relative to the comparison

groups at post-intervention and at 4-month followup, these differences were non-significant.

Therefore, the data do not demonstrate reliably that

improvements in quality of life emerged as a result of

the intervention.

Figure 2. ORS data for intervention and comparison groups.

93

Relationship of improvement in anger control

to other factors

The overall improvement shown by clients in the

intervention group (anger level change, calculated as

the difference between NAS scores at pre-intervention and post-intervention) correlated significantly

with CPM performance (r 5 2.56, p,.05), whereas

the correlation with PPVT-III performance

(r 5 2.21) was non-significant. These findings suggest an association between improvements in anger

and level of nonverbal reasoning abilities, but not

with level of receptive vocabulary. A linear regression

analysis (see Table 4) was undertaken to examine the

contribution of the variables of age, gender, primary

mode of communication, CPM performance and

PPVT-III performance. This analysis reveals the

only variable to account for significant variance in

improvements in anger was CPM performance.

Conversely, the variables of age, gender, primary

mode of communication and PPVT-III performance

did not contribute significantly to changes in anger

levels for the intervention group.

Discussion

The research demonstrates that individuals who

participated in an intervention group showed relative

improvements in self-reported levels of anger

between pre- and post-intervention, with treatment

94

N. Hagiliassis et al.

Table 4. Results of multiple linear regression showing the

relationship of change in anger level to other variables

Variables

Downloaded by [Nanyang Technological University] at 14:07 17 June 2014

Model summary

CPM score

PPVT-III score

Age

Gender

Primary communication

mode

R2 R2 change

.309

.309

Beta

Significance

2.556

2.556

2.094

2.471

2.432

.391

.039

.039

.718

.109

.081

.120

effects maintained at 4-month follow-up. In contrast, anger levels of individuals from the comparison

groups remained relatively stable over the same

period. From this, it may be concluded that the

therapeutic approach examined in the present study

was successful in reducing levels of anger in

individuals with a range of levels of intellectual

disability and complex communication needs. As

already indicated, CPM and PPVT-III scores confirm that individuals representative of a range of

cognitive abilities, including those with moderate to

severe intellectual disabilities, were sampled in the

study. Additionally, there was a spread of communication abilities sampled, ranging from clients who

used speech as their primary form of communication, to clients who employed a range of nonverbal

communication methods, such as electronic communication devices and communication boards.

Given the paucity of specialised anger management

programs for individuals with disabilities with a

range of cognitive and/or communication abilities,

the finding is a welcome outcome. Effectively,

the finding extends the range of evidence-based

resources available to practitioners for delivering

interventions for individuals with anger control

issues and disabilities.

In contrast to observed improvement in anger

levels, there was an absence of measured changes in

quality of life for the intervention group compared

with the comparison group. Although there was no a

priori reason for expecting a relationship to emerge

between participation in an anger intervention group

and improvements in quality of life, the potential

finding of such a relationship would have

nevertheless been a positive outcome. However, this

was not the case. One possibility is that the benefits

of the intervention are restricted to improvements in

anger control, rather than improvements in other

psychological domains, such as quality of life.

Another possibility is that the measure itself was

not robust for this client group. Despite its selection

as a tool with promising utility for the assessment of

treatment outcomes for individuals with disabilities,

there are no specific psychometric data available on

the ORS and its use with people with disabilities.

Further investigation of the link between anger and

quality of life in individuals with disabilities would

seem a useful direction for future research, as would

the accumulation of further psychometric data on

tools used to measure these constructs.

The present study has a number of methodological strengths. Foremost, the study was a randomised

controlled trial of an anger management intervention

in individuals with disabilities. The only other

identified randomised controlled trial is that of

Willner et al. (2002), who found similarly that

clients in their intervention group showed improvements in anger control relative to their own preintervention scores, and to their comparison group

post-intervention. However, the results of the present study potentially have greater generalisability as

a larger sample was used (N 5 29) compared with

the Willner et al. (2002) study (N 5 14). Clearly, a

focus for future research examining the efficacy of

anger management training programs for individuals

with disabilities should be more controlled investigations with larger sample numbers so that researchers

may have greater confidence in the inferences they

draw from their findings. Other strengths of the

present study, that would also appear to be valuable

inclusions for future research, are the reporting of

robust data in order to objectively quantify the

effects of the intervention, the presentation of client

characteristics in order to aid the interpretation of

findings, and the provision of adequate reference to

the content of the program in order to allow its

replication elsewhere.

Despite the aforementioned strengths, there are

also a number of potential limitations of the study.

Even though the research was a randomised controlled study, the randomised controlled nature of

the research may have been further enhanced by the

inclusion of a second comparison group, one which

was involved in a placebo group activity. This would

have provided the researchers with even greater

confidence that the improvements seen were as a

result of the intervention, as opposed to being an

artefact of participation in a group. Additionally,

although the study involved larger numbers of

participants than a previous randomised controlled

trial, the sample size used in the present study is by

no means exhaustive, and a direction for future

research would be replication with a larger sample.

Another potential limitation of the present study is

the absence of carer reports as an external validation

of the improvements in self-reported levels of anger

of clients in the intervention group. This was a

conscious decision on the part of the researchers

Downloaded by [Nanyang Technological University] at 14:07 17 June 2014

The Anger Management Project

who, in line with client-centred practice, were

interested in being guided by the clients own

perception of their anger and its impact.

Notwithstanding this position, qualitative data collected through informal discussions indicated that

many carers felt participants were more in control of

their own anger on completion of the program. The

only exception to this was a carer for a client who

showed a deterioration in her anger control following

the program; this carer identified an exacerbation of

challenging behaviours for that client. While it would

seem useful for researchers to consider the question

of concurrent validation of clients self-reports of

anger, such as through the use of carer reports, the

decision should also be considered in the context of

client-centred practice.

Another question concerns the role of carers in the

program. To recapitulate, in addition to the two

facilitators, two carers participated in one of the

intervention groups. It is unclear what the impact of

introducing this element into the treatment process

was since no objective data were collected on this

factor. However, anecdotal observations suggest that

the inclusion of carers had a positive impact on client

outcomes overall. Beyond carers providing practical

assistance with the delivery of activities and roleplays, they appeared to play a valuable role in terms

of ensuring that the skills learnt in the context of a

group program were generalised across other settings, such as home, day service or work settings.

Along a similar line, evidence for the role of carers

in supporting skill generalisation is presented by

Willner et al. (2002), who noted that clients who

achieved the best outcomes were those accompanied

to the group by carers. Additionally, it appeared that

through their involvement with the program, carers

became more conversant with anger management

techniques, building on their capacity to work

effectively with clients with anger management

issues in the future. As pointed out also by Rose

et al. (2000), a direction for future research would be

to examine the influence of carers in producing and

maintaining change.

Additionally, while the results of the research

provide reliable evidence of the effectiveness of the

program in reducing self-reported levels of anger in

people with disabilities, precisely which elements of

the program were most responsible for producing

this change is unclear. The techniques that appeared

to be most useful were those reflecting the physiological (e.g., relaxation) and behavioural (e.g.,

problem-solving) components of the program. In

contrast, participants appeared to have more difficulty with the cognitive elements of the program.

This opinion has also been expressed by others

95

investigating similar programs (e.g., Rose et al.,

2000; Taylor et al., 2002; Willner et al., 2002), who

acknowledge that the cognitive components of such

programs are perhaps the most difficult to employ

with individuals with intellectual disability. Further

research is required to determine which of the

physiological, behavioural and cognitive components

of the program, or combinations thereof, are more

responsible for producing change.

Another interesting finding was a significant

negative correlation between CPM performance

and change in anger scores demonstrated by

participants from the intervention groups. This

result suggests that individuals with more significant

nonverbal reasoning deficits showed greater

improvements in anger control as a result of the

intervention, although it is important to emphasise

that clients with higher level nonverbal skills also

benefited from the program. The reasons for this

finding are not entirely clear, but the possibility

remains that some aspects of the program (e.g.,

pictographic materials, pace) may have been more

suited to individuals functioning in the lower range

of nonverbal abilities. The result is in contrast to the

findings of Willner et al. (2002), who found a nonsignificant correlation between nonverbal IQ and

anger outcomes for their intervention group. While it

is difficult to ascertain the source of these inter-study

variations, possible contributing factors include

differences in participant characteristics, as well as

differences in the actual anger management programs evaluated by each investigation. On an

associated matter, a somewhat perplexing result is

the observation of a significant correlation between

treatment outcomes for the intervention group and

performance on the CPM, but a non-significant

correlation between outcome and performance on

the PPVT-III. A regression analysis confirmed that

reasoning ability, as assessed using the CPM, was a

significant predictor of improvement, while receptive

vocabulary, as assessed using the PPVT-III, did not

contribute substantially to group outcomes. It is

possible that the programs emphasis on visual and

active learning techniques meant that nonverbal

reasoning skills were more likely to influence

intervention outcomes compared with receptive

vocabulary. However, this is a tentative hypothesis

insofar as the cognitive factors that underpin

successful outcomes in anger management programs

are poorly understood. Further research is required

to explicate these relationships.

In conclusion, the present study provides reliable

evidence of the effectiveness of this anger management intervention for individuals with a range

of levels of intellectual disability and/or complex

96

N. Hagiliassis et al.

communication needs. Beyond reinforcing the usefulness of specialised anger management programs as

interventions for individuals with disabilities, the

present study serves to highlight the importance of

continued research in the area, using a robust

research methodology. Through expanding the evidence base, practitioners will have greater confidence

in delivering interventions in the area, ultimately

making a substantial difference in the lives of clients

with disabilities with anger support needs.

Downloaded by [Nanyang Technological University] at 14:07 17 June 2014

Author note

This research was considered and approved by the

Human Research Ethics Committee at RMIT

University.

Note

1 Scope is an organisation providing services to over 3,500

children and adults with physical and multiple disabilities in

Victoria, Australia.

References

Benson, B. A. (1992). Teaching anger management to persons with

mental retardation. Worthington, OH: IDS Publishing.

Benson, B. A., Johnson Rice, C., & Miranti, S. V. (1986). Effects

of anger management training with mentally retarded adults in

group treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology,

54, 728729.

Black, L., Cullen, C., & Novaco, R. W. (1997). Anger assessment

for people with mild learning disabilities in secure settings. In

B. Stenfert Kroese, D. Dagnan & K. Loumidis (Eds.),

Cognitive-behaviour therapy for people with learning disability.

London: Routledge.

Dunn, L. M., & Dunn, L. M. (1997). Peabody Picture Vocabulary

Test (3rd ed.). Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

Gilmour, K. (1998). An anger management programme for adults

with learning disabilities. International Journal of Language and

Communication Disorders, 33, 403408.

Gulbenkoglu, H., & Hagiliassis, N. (2002). The Anger

Management Training Package: For people with disabilities.

Melbourne: Scope.

Hill, B. K., & Bruininks, R. H. (1984). Maladaptive behavior of

mentally retarded individuals in residential facilities. American

Journal of Mental Deficiency, 88, 380387.

Holbrook Freeman, L., & Freeman Adams, P. (1999).

Comparative effectiveness of two training programmes on

assertive behaviour. Nursing Standard, 13, 3235.

Howells, P. M., Rogers, C., & Wilcock, S. (2000). Evaluating a

cognitive/behavioural approach to teaching anger management

skills to adults with learning disabilities. British Journal of

Learning Disabilities, 28, 137142.

Kiernan, C. (1991). Service for people with mental handicap and

challenging behaviour in the North West. In J. Harris (Ed.),

Service responses to people with learning difficulties and challenging

behaviour, BIMH Seminar Papers No. 1. Kidderminster

British Institute of Mental Handicap.

King, N., Lancaster, N., Wynne, G., Nettleton, N., & Davis, R.

(1999). Cognitive-behavioural anger management training for

adults with mild intellectual disability. Scandinavian Journal of

Behaviour Therapy, 28, 1922.

Miller, S. D., & Duncan, B. L. (2000). The Outcome Rating Scale.

Chicago: Authors.

Novaco, R. W. (1975). Anger control: The development and

evaluation of an experimental treatment. Lexington, MA: Heath.

Novaco, R. W. (1986). Anger as a clinical and social problem. In

R. Blanchard & C. Blanchard (Eds.), Advances in the study of

aggression, Vol. II. New York: Academic Press.

Novaco, R. W. (1994). Anger as a risk factor for violence among

the mentally disordered. In J. Monahan & H. Steadman

(Eds.), Violence and mental disorder: Developments in risk

assessment. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Raven, J., Raven, J. C., & Court, J. H. (1998). Manual for Ravens

Progressive Matrices and Vocabulary Scales. Oxford: Oxford

Psychologists Press.

Rose, J. (1996). Anger management: A group treatment program

for people with mental retardation. Journal of Developmental

and Physical Disabilities, 8, 133149.

Rose, J., West, C., & Clifford, D. (2000). Group interventions for

anger in people with intellectual disabilities. Research in

Developmental Disabilities, 21, 171181.

Rossiter, R., Hunnisett, E., & Pulsford, M. (1998). Anger

management training and people with moderate to severe

learning disabilities. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 26,

6774.

Sigafoos, J., Elkins, J., Kerr, M., & Attwood, T. (1994). A survey

of aggressive behaviour among a population of persons with

intellectual disability in Queensland. Journal of Intellectual

Disability Research, 38, 369381.

Smith, S., Branford, D., Collacott, R. A., Cooper, S. A., &

McGrother, C. (1996). Prevalence and cluster typology of

maladaptive behaviours in a geographically defined population

of adults with learning disabilities. British Journal of Psychiatry,

169, 219227.

Spielberger, C. D. (1991). State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory:

Revised research edition professional manual. Odessa, FL:

Psychological Assessment Resources.

Taylor, J. L. (2002). A review of assessment and treatment of

anger and aggression in offenders with intellectual disability.

Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 46, 5773.

Taylor, J. L., Novaco, R. W., Gillmer, B., & Thorne, I. (2002).

Cognitive-behavioural treatment of anger intensity in offenders with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in

Intellectual Disabilities, 15, 151165.

Turk, V., & Francis, E. (1990). An anxiety management group:

Strengths and pitfalls. Mental Handicap, 18, 7881.

Whitaker, S. (2001). Anger control for people with learning

disabilities: A critical review. Behavioural and Cognitive

Psychotherapy, 29, 277293.

Willner, P., Jones, J., Tams, R., & Green, G. (2002). A

randomised controlled trial of the efficacy of a cognitivebehavioural anger management group for adults with learning

disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities,

15, 224235.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- 1984.anger and Aggression - An Essay On Emotionby James R. Averill PDFDocumento3 pagine1984.anger and Aggression - An Essay On Emotionby James R. Averill PDFHanaeeyemanNessuna valutazione finora

- (Alpay) Self-Concept and Self-Esteem in Children A PDFDocumento5 pagine(Alpay) Self-Concept and Self-Esteem in Children A PDFHanaeeyemanNessuna valutazione finora

- Youth Violence NSF PDFDocumento69 pagineYouth Violence NSF PDFHanaeeyemanNessuna valutazione finora

- PaperDocumento11 paginePaperrgr.webNessuna valutazione finora

- PaperDocumento11 paginePaperrgr.webNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Aggression in Children and Adolescents - A Meta-Analytic Re PDFDocumento121 pagineSocial Aggression in Children and Adolescents - A Meta-Analytic Re PDFHanaeeyemanNessuna valutazione finora

- Anger Episodes PDFDocumento19 pagineAnger Episodes PDFHanaeeyemanNessuna valutazione finora

- Academic Achievement AssessmentDocumento15 pagineAcademic Achievement AssessmentRochelle EstebanNessuna valutazione finora

- A Self-Assessment Tool PDFDocumento7 pagineA Self-Assessment Tool PDFHanaeeyemanNessuna valutazione finora

- Aggressive Behavior in Dogs PDFDocumento3 pagineAggressive Behavior in Dogs PDFHanaeeyemanNessuna valutazione finora

- Studies On Anger and Aggression: Implications For Theories of EmotionDocumento16 pagineStudies On Anger and Aggression: Implications For Theories of EmotionHanaeeyeman100% (1)

- Sadness, Anger, and Frustration - Gendered Patterns in Early Adolescents' and Their Parents' Emotion Talk PDFDocumento11 pagineSadness, Anger, and Frustration - Gendered Patterns in Early Adolescents' and Their Parents' Emotion Talk PDFHanaeeyemanNessuna valutazione finora

- Buss Perry Aggression QuestionnaireDocumento4 pagineBuss Perry Aggression QuestionnaireKaty Graham100% (1)

- APA StyleDocumento5 pagineAPA Stylevsop_bluezzNessuna valutazione finora

- Norma APADocumento6 pagineNorma APAWilliam MarinezNessuna valutazione finora

- Passive Assertive Aggressive 2004-09-01Documento1 paginaPassive Assertive Aggressive 2004-09-01HanaeeyemanNessuna valutazione finora

- ProposalDocumento11 pagineProposalapi-302389888Nessuna valutazione finora

- Cara Menulis Rujukan-Apa StyleDocumento18 pagineCara Menulis Rujukan-Apa StyleWan AqilahNessuna valutazione finora

- ECBI Child Behavior InventoryDocumento2 pagineECBI Child Behavior InventoryHanaeeyeman0% (1)

- Summary of Guidelines For Formatting References According To The APA Style Guide: 5th EditionDocumento15 pagineSummary of Guidelines For Formatting References According To The APA Style Guide: 5th EditionHanaeeyemanNessuna valutazione finora

- COPING MEASURE ASSESSES STRESS RESPONSESDocumento4 pagineCOPING MEASURE ASSESSES STRESS RESPONSESHanaeeyeman100% (8)

- APA Citation GuidesDocumento7 pagineAPA Citation Guidesdr gawdat100% (14)

- Digman On Five Factor ModelDocumento24 pagineDigman On Five Factor ModelHanaeeyeman100% (1)

- Meich 06 GenderdifferencesDocumento27 pagineMeich 06 GenderdifferencesHanaeeyemanNessuna valutazione finora

- Emotional DisturbancesDocumento8 pagineEmotional DisturbancesHanaeeyemanNessuna valutazione finora

- Ramirez 2001 AggressionDocumento10 pagineRamirez 2001 AggressionHanaeeyemanNessuna valutazione finora

- ECBI Child Behavior InventoryDocumento2 pagineECBI Child Behavior InventoryHanaeeyeman0% (1)

- Brestan Et Al 1999Documento14 pagineBrestan Et Al 1999HanaeeyemanNessuna valutazione finora

- Brestan Et Al 1999Documento14 pagineBrestan Et Al 1999HanaeeyemanNessuna valutazione finora

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Facial Expression Recognition CNN SurveyDocumento4 pagineFacial Expression Recognition CNN Surveypapunjay kumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Psychosocial Care in Disasters ToT NIDMDocumento162 paginePsychosocial Care in Disasters ToT NIDMVaishnavi JayakumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Other Characteristics of Filipino Values and Orientation-WordDocumento2 pagineOther Characteristics of Filipino Values and Orientation-WordErica CanonNessuna valutazione finora

- Case StudiesDocumento2 pagineCase StudiesMohankumar0205100% (5)

- Psychology Lecture on Subject, Objectives and FieldsDocumento5 paginePsychology Lecture on Subject, Objectives and FieldsMaira456Nessuna valutazione finora

- EthicsDocumento5 pagineEthicsYi-Zhong TanNessuna valutazione finora

- GEB Module 1 ExerciseDocumento5 pagineGEB Module 1 ExerciseQuyen DinhNessuna valutazione finora

- Manikchand Oxyrich WaterDocumento30 pagineManikchand Oxyrich Watergbulani11Nessuna valutazione finora

- Principles of Management 1: Chapter One Part 3: Management HistoryDocumento17 paginePrinciples of Management 1: Chapter One Part 3: Management HistoryWalaa ElsharifNessuna valutazione finora

- Wim Hof Method Ebook The Journey of The Iceman PDFDocumento17 pagineWim Hof Method Ebook The Journey of The Iceman PDFJaine Cavalcante100% (5)

- The New Burdens of MasculinityDocumento8 pagineThe New Burdens of MasculinityhamzadurraniNessuna valutazione finora

- English 9 Quarter 3 Week 3 2Documento4 pagineEnglish 9 Quarter 3 Week 3 2Sector SmolNessuna valutazione finora

- I/O Reviewer Chapter 12Documento3 pagineI/O Reviewer Chapter 12luzille anne alerta100% (1)

- English DLL Week 1 Qrtr.4 AvonDocumento7 pagineEnglish DLL Week 1 Qrtr.4 Avonlowel borjaNessuna valutazione finora

- 1901 BTEC Firsts Grade BoundariesDocumento4 pagine1901 BTEC Firsts Grade BoundariesGamer BuddyNessuna valutazione finora

- Lessons in Leadership For Person-Centered Elder Care (Excerpt)Documento10 pagineLessons in Leadership For Person-Centered Elder Care (Excerpt)Health Professions Press, an imprint of Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co., Inc.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Everyday Teachings of Gurudev Paramahamsa HariharanandaDocumento5 pagineEveryday Teachings of Gurudev Paramahamsa HariharanandaYogi Sarveshwarananda GiriNessuna valutazione finora

- A Lie Can Travel Halfway Around The World While The Truth Is Putting On Its ShoesDocumento2 pagineA Lie Can Travel Halfway Around The World While The Truth Is Putting On Its ShoesProceso Roldan TambisNessuna valutazione finora

- UnityDocumento39 pagineUnitymonalNessuna valutazione finora

- The Compound Effect by Darren HardyDocumento15 pagineThe Compound Effect by Darren HardyJB Arquero33% (3)

- Defensive coping nursing diagnosisDocumento3 pagineDefensive coping nursing diagnosisRoch Oconer100% (1)

- A Guide To Endorsed Resources From CambridgeDocumento2 pagineA Guide To Endorsed Resources From CambridgesamNessuna valutazione finora

- Unilab CSR PDFDocumento24 pagineUnilab CSR PDFJennefer GemudianoNessuna valutazione finora

- Educ 101 Module 1Documento12 pagineEduc 101 Module 1Kyle GomezNessuna valutazione finora

- Bensky Dog Psychology Large ReviewDocumento198 pagineBensky Dog Psychology Large ReviewShaelynNessuna valutazione finora

- Diaspora Action Australia Annual Report 2012-13Documento24 pagineDiaspora Action Australia Annual Report 2012-13SaheemNessuna valutazione finora

- Ferreiro, Metodo ELI - Juan RodulfoDocumento159 pagineFerreiro, Metodo ELI - Juan RodulfoAngélica CarrilloNessuna valutazione finora

- Gender Law (Bartlett)Documento3 pagineGender Law (Bartlett)Zy AquilizanNessuna valutazione finora

- How People Navigate Urban EnvironmentsDocumento4 pagineHow People Navigate Urban EnvironmentsJames AsasNessuna valutazione finora

- A Search of Different Maladjusted Behavi PDFDocumento10 pagineA Search of Different Maladjusted Behavi PDFDurriya AnisNessuna valutazione finora