Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Stanley Fine Furniture Et Al V Gallano and Siarez PDF

Caricato da

Anonymous nYvtSgoQTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Stanley Fine Furniture Et Al V Gallano and Siarez PDF

Caricato da

Anonymous nYvtSgoQCopyright:

Formati disponibili

G.R. No.

190486

8/31/15 10:21 PM

Today is Monday, August 31, 2015

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

SECOND DIVISION

G.R. No.190486

November 26, 2014

STANLEY FINE FURNITURE, ELENAAND CARLOS WANG, Petitioners,

vs.

VICTOR T. GALLANO AND ENRIQUITO SIAREZ, Respondents.

DECISION

LEONEN, J.:

To terminate the employment of workers simply because they asserted their legal rights by filing a complaint is

illegal. It violates their right to security of tenure an'd should not be tolerated.

In this petition for review1 on certiorari filed by Elena Briones,2 we are asked to reverse the decision3 of the Court of

Appeals in CA-G.R. SP No. 101145. The Court of Appeals found grave abuse of discretion on the part of the

National Labor Relations Commission, and reinstated the decision of the Labor Arbiter dated August 2, 2006 finding

that respondents Victor Gallano and Enriquito Siarez were illegally dismissed.4

Stanley Fine Furniture (Stanley Fine), through its owners Elena and Carlos Wang, hired respondents Victor T.

Gallano and Enriquito Siarez in 1995 as painters/carpenters. Victor and Enriquito each received 215.00 basic salary

per day.5

On May 26, 2005, Victor and Enriquito filed a labor complaint6 for underpayment/non-payment of salaries, wages,

Emergency Cost of Living Allowance (ECOLA), and 13th month pay. They indicated in the complaint form that they

were "still working"7 for Stanley Fine.

Victor and Enriquito filed an amended complaint8 on May 31, 2005, for actual illegal dismissal, underpayment/nonpayment of overtime pay, holiday pay, premium for holiday pay, service incentive leave pay, 13th month pay,

ECOLA, and Social Security System (SSS) benefit. In the amended complaint, Victor and Enriqui to claimed that

they were dismissed on May 26, 2005.9 Victor and Enriquito were allegedly scolded for filing a complaint for money

claims. Later on, they were not allowed to work.10

On the other hand, petitioner Elena Briones claimed that Victor and Enriquito were "required to explain their

absences for the month of May 2005, but they refused."11

In the decision12 dated August 2, 2006, the Labor Arbiter found that Victor and Enriqui to were illegally dismissed.

The Labor Arbiter noted the following contradictory statements inStanley Fines position paper, thus:

Also, Stanley Fine was forced todeclare them dismissed due to their failure to report back to work for a considerable

length of time and also, due to the filing of an unmeritorious labor case against it by the two complainants. . . .

....

The main claim of the complainants is their allegation that they were dismissed. They were NOT DISMISSED.13

(Emphasis in the original)

The Labor Arbiter resolved these contradictory statements in the following manner:

http://www.lawphil.net/judjuris/juri2014/nov2014/gr_190486_2014.html

Page 1 of 14

G.R. No. 190486

8/31/15 10:21 PM

In fact, the admission that complainants were dismissed due to the filing of a case against them by complainants is

a blatant transgression of the Labor Code that no retaliatory measure shall be levelled against an employee by

reason of an action commenced against an employer. This is virtually a confession of judgment and a death [k]nell

to the cause of respondents. It actually lends credence tothe fact that complainants were dismissed upon

respondents knowledge of the complaint before the NLRC as attested by the fact that four days after the filing of the

complaint, the same was amended to include illegal dismissal.14

The Labor Arbiter also awarded moral and exemplary damages to respondents, reasoning that: Finding malice, and

ill-will in the dismissal of complainants, which exhibits arrogance and defiance of labor laws on the part of

respondents, moral and exemplary damages for P50,000 and P30,000 respectively for each of the complainants are

hereby granted.

WHEREFORE, premises considered, respondents are hereby declared guilty of illegal dismissal. As a

consequence, they are ORDERED to reinstate complainant to their former position and pay jointly and severally

complainants full backwages from date of dismissal until actual reinstatement[.]15

On appeal, the National Labor Relations Commission reversed16 the Labor Arbiters decision, ruling that the Labor

Arbiter erred in considering the statement, "due to the filing ofan unmeritorious labor case," as an admission against

interest.17 The National Labor Relations Commission held that:

Contrary to the findings of the Labor Arbiter below . . . respondents-appellants allegations in paragraph 5 of their

position paper is not an admission that they dismissed complainants-appellees moreso [sic], in retaliation for

complainants-appellees filing a complaint against them. Had the Labor Arbiter been more circumspect analyzing the

facts brought before him by the herein parties pleadings, he could have easily discerned that complainantsappellees were merely required to explain their unauthorized absences they committed for the month of May 2005

alone. Complainants-appellees did notdeny knowledge of the memoranda issued to them on May 23, 25 and 27,

2005 for complainant-appellee Siarez and June 1, 2005 memo for Gallano. That they simply refused receipt of them

cannot extricate themselves from its legal effects as the last of which clearly show that itwas sent to them thru the

mails.

....

The same holds true with the findings of the Labor Arbiter below that respondents-appellants evidence, Annexes "7"

to "74" "cannot be admissible in evidence" for being mere xerox copies and "are easily subjected to interpolation

and tampering."

Suffice it to state that these pieces of evidence were adduced during the arbitral proceedings below, where

complainants-appellees were afforded the opportunity to controvert and deny its truthfulness and veracity that

complainants-appellees never objected thereto or deny its authenticity, certainly did not render said documents

tampered or interpolated.

WHEREFORE, in view of the foregoing, the decision appealed from is hereby REVERSEDand SET

ASIDE.Respondents-appellants are however ordered to reinstate complainants-appellees to their former position

without loss of seniority rights and benefits appurtenant thereto, without backwages.

SO ORDERED.18

Victor and Enriquito filed a motion for reconsideration,19 which the National Labor Relations Commission denied in

the resolution20 dated August 15, 2007.

Thus, Victor and Enriquito filed a petition for certiorari before the Court of Appeals. Generally, petitions for certiorari

are limited to the determination and correction of grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of

jurisdiction. However,the Court of Appeals reviewed the findings of facts and of law of the labor tribunals,

considering that the Labor Arbiter and the National Labor Relations Commission had different findings.21

The Court of Appeals found that Stanley Fine failed to show any valid cause for Victor and Enriquitos termination

and to comply with the twonotice rule.22 Also, the Court of Appeals noted that Stanley Fines statements that it

was "forced to declare them dismissed"23 due to their absences and "due to the filing of an unmeritorious labor case

against it by the two complainants"24 were admissions against interest and binding upon Stanley Fine. Thus: An

admission against interest is the best evidence which affords the greatest certainty of the facts in dispute since no

man would declare anything against himself unless such declaration is true. Thus, an admission against interest

http://www.lawphil.net/judjuris/juri2014/nov2014/gr_190486_2014.html

Page 2 of 14

G.R. No. 190486

8/31/15 10:21 PM

man would declare anything against himself unless such declaration is true. Thus, an admission against interest

binds the person who makes the same, and absent any showing that this was made thru palpable mistake, no

amount of rationalization can offset it.25

The Court of Appeals also held that the immediate amendment of Victor and Enriquitos complaint negated their

alleged abandonment.26

With regard to the National Labor Relations Commissions deletion of the monetary award, the Court of Appeals

ruled that:

Notably, private respondents claim of payment is again belied by their own admission in their position paper that

they failed to pay petitioners their ECOLA and to ask for exemption from payment of said benefits to their

employees. In any event, private respondents allegation of payment of money claims is not supported by

substantial evidence. The Labor Arbiter found that the documents presented by private respondents were mere

photocopies, with no appropriate signatures of petitioners and could be easily subjected to interpolation and

tampering.27

The Court of Appeals, thus, granted the petition, set aside the resolutions of the National Labor Relations

Commission, and reinstated the decision of the Labor Arbiter.28 The dispositive portion of its decision reads:

WHEREFORE, the assailed Resolutions dated June 18, 2007 and August 15, 2007 of public respondent NLRC are

set aside and the Labor Arbiters Decision dated August 2, 2006 is reinstated.

SO ORDERED.29

Stanley Fine filed a motion for reconsideration,30 which the Court of Appeals denied in the resolution31 dated

November 27, 2009.

On December 21, 2009, Stanley Fine, Elena, and Carlos Wang filed a motion for extension of time to file petition for

review on certiorari.32

On January 21, 2010, Elena Briones filed a petition for review.33 Elena alleged that she is the "registered

owner/proprietress of the business operation doing business under the name and style Stanley Fine Furniture."34

She argued that the Court of Appeals erred in ruling that Victor and Enriquito were illegally dismissed considering

that she issued several memoranda to them, but they refused to accept the memoranda and explain their

absences.35 As to the statement, "due to the filing of an unmeritorious labor case,"36 it was error on the part of her

former counsel which should not bind her.37 Further, the monetary claims should not have been awarded because

these were based on the allegations in the complaint form,38 whereas Elena presented documentary evidence to

show that Victor and Enriquitos money claims had been paid. They never rebutted her documentary evidence.39 As

to the award of moral and exemplary damages and attorneys fees, Victor and Enriquito did not present any

evidence to support their claim, thus, it was error for the Court of Appeals to have reinstated the Labor Arbiters

decision.40

In compliance with this courts resolution41 dated February 17, 2010, Victor and Enriquito filed their comment42 and

argued that the petition should be denied because Elena "is neither the respondent, party in interest or

representatives as parties."43 With regard to Victors two absences and Enriquitos five absences, these should not

be interpreted as refusal to go back to work tantamount to abandonment.44 Considering that Elenas arguments had

been passed upon by the labor tribunals and the Court of Appeals, this petition should be denied.45

Elena filed her reply46 and posited that she has legal standing to file the petition for review because she isthe

owner/proprietress of Stanley Fine.47 In addition, she argued that Victor and Enriquito knew that she, Elena, is the

real party-in-interest because during the pendency of the labor case, she filed an ex-parte manifestation, attaching

her Department of Trade and Industry certificate of registration of business name,48 showing that the registration is

under her maiden name, Elena Y. Briones. As per the Department of Trade and Industrys certification,49 Stanley

Fine is a sole proprietorship owned by "Elena Briones Yam-Wang." Thus, this court is asked to resolve procedural

and substantive issues in this petition as follows:>

1. Whether Elena Briones has standing to file this petition for review on certiorari;

2. Whether the Court of Appeals erred in ruling that Victor Gallano and Enriquito Siarez were illegally

dismissed;

http://www.lawphil.net/judjuris/juri2014/nov2014/gr_190486_2014.html

Page 3 of 14

G.R. No. 190486

8/31/15 10:21 PM

3. Whether the Court of Appeals erred when it agreed with the Labor Arbiter that the statement, "filing of an

unmeritorious labor case," is an admission against interest and binding against Stanley Fine Furniture; and

4. Whether the Court of Appeals erred in awarding the monetary claims and damages to Victor Gallano and

Enriquito Siarez, considering that they did not produce evidence to support their claims.

I.

Petitioner Elena Briones has standing to file this case

On this issue, petitioners claimed that Elena Briones is not the real party-in-interest; hence, the decision of the Court

of Appeals is final and executory since the petition for review was not properly filed.50

In her reply, Elena argued that she is the sole proprietor of Stanley Fine, a fact known to respondents.51 As the sole

proprietor, she has standing to file this petition.52

Respondents cannot deny Elena Briones standing to file this petition considering that in their amended complaint

filed before the Labor Arbiter, they wrote "Stanley Fine Furniture, Elina [sic] Briones Wang as ownerand Carlos

Wang" as their employers.53

Also, respondents did not refute Elenas allegation that Stanley Fine is a sole proprietorship. In Excellent Quality

Apparel, Inc. v. Win Multi-Rich Builders, Inc.,54 this court stated that:

A sole proprietorship does not possess a juridical personality separate and distinct from the personality of the owner

of the enterprise. The law merely recognizes the existence of a sole proprietorship as a form of business

organization conducted for profit by a single individual and requires its proprietor or owner to secure licenses and

permits, register its business name, and pay taxes to the national government. The law does not vest a separate

legal personality on the sole proprietorship or empower it to file or defend an action in court.55 (Emphasis supplied)

Thus, Stanley Fine, being a sole proprietorship, does not have a personality separate and distinct from its owner,

Elena Briones. Elena, being the proprietress of Stanley Fine, can be considered as a real party-in-interest and has

standing to file this petition for review.

II.

Review of procedural parameters

In her petition for review, Elena raised the following issues: (a) whether "the filing of an Establishment Termination

Report"56 is an act of dismissal; (b) whether counsels allegation that an employee was dismissed due to the filing of

an "unmeritorious" case against the employer is binding;57 (c) whether a Labor Arbiter can award monetary claims

based on the allegations in the complaint form;58 and (d) whether the award of moral and exemplary damages and

attorneys fees is proper even without supporting evidence.59

In a Rule 45 petition for review of a Court of Appeals decision rendered under Rule 65, this court is guided by the

following rules:

[I]n a Rule 45 review (of the CA decision rendered under Rule 65), the question of law that confronts the Court is the

legal correctness of the CA decision i.e., whether the CA correctly determined the presence or absence of grave

abuse of discretion in the NLRC decision before it, and not on the basis of whether the NLRC decision on the merits

of the case was correct. . . . Specifically, in reviewing a CA labor ruling under Rule 45 of the Rules of Court, the

Courts review is limited to:

(1) Ascertaining the correctness of the CAs decision in finding the presence or absence of a grave abuse of

discretion. This is done by examining, on the basis of the parties presentations, whether the CA correctly

determined that at the NLRC level, all the adduced pieces of evidence were considered; no evidence which

should not have been considered was considered; and the evidence presented supports the NLRC findings;

and

(2) Deciding any other jurisdictional error that attended the CAs interpretation or application of the law.60

(Citation omitted)

Thus, the proper issue in this case is whether the Court of Appeals correctly determined the presence of grave

abuse of discretion on the part of the National Labor Relations Commission. III.

http://www.lawphil.net/judjuris/juri2014/nov2014/gr_190486_2014.html

Page 4 of 14

G.R. No. 190486

8/31/15 10:21 PM

There was no just cause in the dismissal of respondents

The Court of Appeals found grave abuse of discretion on the part of the National Labor Relations Commission when

it reversed the Labor Arbiters decision. The Court of Appeals held that respondents were illegally dismissed

because no valid causefor dismissal was shown. Also, there was no compliance withthe two-notice requirement.61

Elena admitted that no notices of dismissal were issued to respondents. However, memoranda were given to

respondents, requiring them to explain their absences. She claimed that the notices to explain disprove

respondents allegation that there was intent to dismiss them.62

Grounds for termination of employment are provided under the Labor Code.63 Just causes for termination ofan

employee are provided under

Article 282 of the Labor Code: ARTICLE 282. Termination by employer.- An employer may terminate an

employment for any of the following causes:

(a) Serious misconduct or willful disobedience by the employee of the lawful orders of his employer or

representative in connection with his work;

(b) Gross and habitual neglect by the employee of his duties;

(c) Fraud or willful breach by the employee of the trust reposed in him by his employer or duly authorized

representative;

(d) Commission of a crime or offense by the employee against the person of his employer or any immediate

member of his family or his duly authorized representatives; and

(e) Other causes analogous to the foregoing.

Although abandonment of work is not included in the enumeration, this court has held that "abandonment is a form

of neglect of duty."64 To prove abandonment, two elements must concur:

1. Failure to report for work orabsence without valid or justifiable reason; and

2. A clear intention to sever the employer-employee relationship.65

In Hodieng Concrete Products v. Emilia,66 this court held that:

Absence must be accompanied by overt acts unerringly pointing to the fact that the employee simply does not want

to work anymore. And the burden of proof to show that there was unjustified refusal to go back to work rests on the

employer.67

The Court of Appeals ruled that the alleged abandonment of work is negated by the immediate filing of the complaint

for illegal dismissal on May 31, 2005.68 The Court of Appeals further stated that:

Long standing is the rule that the filing of the complaint for illegal dismissal negates the allegation of abandonment.

Human experience dictates that no employee in his right mind would go through the trouble of filing a case unless

the employer had indeed terminated the services of the employee.69

In this case, Elena failed to pinpoint the overt acts of respondents that show they had abandoned their work. There

was a mere allegation that she was "forced to declare them dismissed dueto their failure to report back to work for a

considerable length of time"but no evidence to prove the intent to abandon work.70 It is the burden of the employer

to prove that the employee was not dismissed or, if dismissed, that such dismissal was not illegal.71 Unfortunately

for Elena, she failed to do so.

IV.

Generally, errors of counsel bind the client

Elenas position paper states the following:

5. Also, Stanley Fine was forced to declare them dismissed due to their failure to report back to work for a

http://www.lawphil.net/judjuris/juri2014/nov2014/gr_190486_2014.html

Page 5 of 14

G.R. No. 190486

8/31/15 10:21 PM

5. Also, Stanley Fine was forced to declare them dismissed due to their failure to report back to work for a

considerable length of time and also, due to the filing of an unmeritorious labor case against itby the two

complainants. . . . (Emphasis supplied)

....

8. The main claim of the complainants is their allegation that they were dismissed. They were NOT

DISMISSED. Management was [sic] has only instructed them to submit a written explanation for their

absence before they would be allowed back to work. . . .72 (Underscoring in the original)

Elena argued that the use of the word "unmeritorious" should not be taken against her because it is commonly used

in pleadings. Also, the use of the word "unmeritorious" came from her previous counsel.73 In an effort to persuade

this court, Elena further argued in her reply that the statement "unmeritorious case" was a mistake committed by her

former counsel which should not bind her, considering its grave consequence.74

On the other hand, respondents alleged in their position paper75 that they were requesting from their employer an

increase in pay to comply with the minimum wage law.76 However, they were reprimanded and were told "not to

work anymore."77

Respondents filed a reply78 to Elenas position paper and argued that:

6. The words "Nag complain pa kayo sa Labor ha, tanggal na kayo" were clear, unequivocal and categorical. These

circumstances were sufficient to create the impression in the mind of complainants and correctly so that their

services were being terminated. The acts of respondents were indicative of their intention to dismiss complainants

from their employment.79

On this issue, the National Labor Relations Commission held that the phrase, "filing of an unmeritorious labor

complaint,"80 if read together with the other allegations in Elenas position paper, would show that respondents were

not dismissed but simply required to explain their absences.81

On the other hand, the Court of Appeals agreed with the Labor Arbiter that Elenas statement is an admission

against interest and binding upon her. The Court of Appeals explained that:

An admission against interest is the best evidence which affords the greatest certainty of the facts in dispute since

no man would declare anything against himself unless such declaration is true. Thus, an admission against interest

binds the person who makes the same, and absent any showing that this was made thru palpable mistake, no

amount of rationalization can offset it.82

The general rule is that errors of counsel bind the client. The reason behind this rule was discussed in Building Care

Corporation v. Macaraeg:83

It is however, an oft-repeated ruling that the negligence and mistakes of counsel bind the client. A departure from

this rule would bring about never-ending suits, so long as lawyers could allege their own fault or negligence to

support the clientscase and obtain remedies and reliefs already lost by operation of law. The only exception would

be, where the lawyers gross negligence would result in the grave injustice of depriving his client of the due process

of law.84 (Citations omitted)

1wphi1

There is not an iota of proof that the lawyer committed gross negligence in this case. That counsel did not reflect his

clients true intentions is a bare allegation. It is not a mere afterthought meant to escape liability for such illegal act.

Elenas counsel reflected the true reason for dismissing respondents. Both position papers state that Elena

dismissed respondents because of the filing of a labor complaint. Thus, the Court of Appeals did not err in affirming

the Labor Arbiters ruling that the statement, "unmeritorious labor complaint," is an admission against interest.

V.

Non-compliance with procedural

due process supports the finding of

illegal dismissal

Assuming that the statement, "filing of an unmeritorious labor case," is not an admission against interest, still, the

Court of Appeals did not err in reinstating the Labor Arbitersdecision. Elena admitted85 that no notices of dismissal

were issued.

Elena pointed out that there is no evidence showing that at the time she sent the memoranda, she already knew of

http://www.lawphil.net/judjuris/juri2014/nov2014/gr_190486_2014.html

Page 6 of 14

G.R. No. 190486

8/31/15 10:21 PM

Elena pointed out that there is no evidence showing that at the time she sent the memoranda, she already knew of

the complaint for money claims filed by respondents.86 The allegation that she told respondents "Nag complain pa

kayo sa Labor ha, sige tanggal na kayo"87 is hearsay and inadmissible.88

In cases of termination of employment, Article 277(b) of the Labor Code provides that:

ARTICLE 277. Miscellaneous provisions.

....

(b) Subject to the constitutional right of workers to security of tenure and their right to be protected against dismissal

except for a just and authorized cause and without prejudice to the requirement of notice under Article 283 of this

Code, the employer shall furnish the worker whose employment is sought to be terminated a written notice

containing a statement of the causes for termination and shall afford the latter ample opportunity to be heard and to

defend himself with the assistance of his representative if he so desires in accordance with company rules and

regulations promulgated pursuant to guidelines set by the Department of Labor and Employment. Any decision

taken by the employer shall be without prejudice to the right of the worker to contest the validity or legality of his

dismissal by filing a complaint with the regional branch of the National Labor Relations Commission. The burden of

proving that the termination was for a valid or authorized cause shall rest on the employer[.]

Book VI, Rule I, Section 2(d) of the Omnibus Rules Implementing the Labor Code further provides:

Section 2. Security of tenure. . . .

....

(d) In all cases of termination of employment, the following standards of due process shall be substantially

observed:

For termination of employment based on just causes as defined in Article 282 of the Code:

(i) A written notice served on the employee specifying the ground or grounds for termination, and giving

said employee reasonable opportunity within which to explain his side.

(ii) A hearing or conference during which the employee concerned, with the assistance of counsel if

heso desires is given opportunity to respond to the charge, present his evidence, or rebut the evidence

presented against him.

(iii) A written notice of termination served on the employee, indicating that upon due consideration of all

the circumstances, grounds have been established to justify his termination. King of Kings Transport,

Inc. v. Mamac89 extensively discussed the two-notice requirement and the procedure that must be

observed in cases of termination, thus:

(1) The first written noticeto be served on the employees should contain the specific causes or

grounds for termination against them, and a directive that the employees are given the

opportunity to submit their written explanation within a reasonable period. "Reasonable

opportunity" under the Omnibus Rules means every kind of assistance that management must

accord to the employees to enable them to prepare adequately for their defense. This should be

construed as a period of at least five (5) calendar days from receipt of the notice to give the

employees an opportunity to study the accusation against them, consult a union official or

lawyer, gather data and evidence, and decide on the defenses they will raise against the

complaint. Moreover, in order to enable the employees to intelligently prepare their explanation

and defenses, the notice should contain a detailed narration of the facts and circumstances that

will serve as basis for the charge against the employees. A general description of the charge will

not suffice. Lastly, the notice should specifically mention which company rules, if any, are

violated and/or which among the grounds under Art. 282 is being charged against the

employees.

(2) After serving the first notice, the employers should schedule and conduct a hearing or

conference wherein the employees will be given the opportunity to: (1) explain and clarify their

defenses to the charge against them; (2) present evidence insupport of their defenses; and (3)

rebut the evidence presented against them by the management. During the hearing or

conference, the employees are given the chance to defend themselves personally, with the

http://www.lawphil.net/judjuris/juri2014/nov2014/gr_190486_2014.html

Page 7 of 14

G.R. No. 190486

8/31/15 10:21 PM

conference, the employees are given the chance to defend themselves personally, with the

assistance of a representative or counsel of their choice. Moreover, this conference or hearing

could be used by the parties as an opportunity to cometo an amicable settlement.

(3) After determining that termination of employment is justified, the employers shall serve the

employees a written notice of termination indicating that: (1) all circumstances involving the

charge against the employees have been considered; and (2) grounds have been established to

justify the severance of their employment.90 (Emphasis in the original, citation omitted)

Elena presented photocopies of the memoranda to prove that notices to explain were sent to respondents. These

photocopies were not considered by the Labor Arbiter, on the ground that they had no probative value. Elena

argued that even if the annexes were mere photocopies, they formed part of the position paper, which is a verified

pleading under oath.91 Elena also cited Lee v. Regional Trial Court of Quezon City, Branch 8592 where this court

allegedly ruled that photocopies of documents attached to a verified motion, which have not been controverted, are

admissible.93

In Lee v. Regional Trial Court of Quezon City, Branch 85, this court stated the following:

Before we discuss the substance of private respondents motion, we note that attached to it weremere photocopies

of the supporting documents and not "certified true copies of documents or papers involved therein" as required by

the Rules of Court. However, given that the motion was verified and petitioners, who were given a chance to oppose

or comment on it, made no objection thereto, we brush aside the defect in form and proceed to discuss the merits of

the motion.94 (Citation omitted)

A review of the decision in Lee v. Regional Trial Court of Quezon City, Branch 85 shows that the case involved an

omnibus motion to cite Jose C. Lee and the other parties in indirect contempt, and to impose disciplinary sanctions

or disbar Jose C. Lees counsel.95 The statement cited by Elena is not the controlling doctrine in that case. In

addition, it appears that this court brushed aside "the defect in form" in the exercise of its discretion and, thus, it

should not be taken as the controllingdoctrine. Hence, no error can be attributed to the Court of Appeals when it

agreed with the Labor Arbiters ruling that the photocopies of the memoranda have no probative value since they are

mere photocopies.96

Even if this court considers Annexes 1 to 5,97 these pieces of evidence would not save Elenas cause. Annexes 1 to

3 are the memoranda issued to Enriquito with a notation that he refused to sign. Annex 2 is dated May 25, 2005, but

the date when Enriquito allegedly refused to sign is not indicated.98 Annex 3 is dated May 23, 2005, but again, the

memorandum does not show when it was served upon Enriquito and the date he refused to sign.99 It is quite

possible that these memoranda were antedated.

Annex 4 is dated June 1, 2005 and was sent to Enriquito Siarez via registered mail.100 Annex 5 is the memorandum

issued to Victor Gallano and is likewise dated June 1, 2005.101 Respondents were allegedly dismissed on May 26,

2005;102 hence, Annex 1 dated May 27, 2005,103 Annex 4 dated June 1, 2005, and Annex 5 also dated June 1,

2005, were issued as a mere afterthought.

VI.

The Court of Appeals did not err in

awarding money claims and damages

With regard to the award of money claims,104 Elena likewise argues that the Labor Arbiter erred in notadmitting

Annexes 7 to 74, citing Lee v. Regional Trial Court of Quezon City, Branch 85. On this matter, the Court of Appeals

quoted the Labor Arbiters decision, stating that:

With respect to Annexes 7 to 74 to prove compliance of labor standards, the same cannot be admissible in evidence

because they are mere Xerox copies which are easily subjected to interpolation and tampering.

Besides, Annex 69 which purports to be payment of 13th month pay for 2004 of complainant Gallano but no amount

is indicated. Again, Annex 71 states 13th month pay for P4,500.00 for complainant Gallano yet there is no signature

of Gallano acknowledging receipt thereof. If one document is tainted with fraud, all other Xerox documents are

fraudulent.105

In their comment, respondents argued that Elenas claim of payment is refuted by her own admission that she did

not pay respondents ECOLA and she even asked for exemption from paying them.106

http://www.lawphil.net/judjuris/juri2014/nov2014/gr_190486_2014.html

Page 8 of 14

G.R. No. 190486

8/31/15 10:21 PM

106

not pay respondents ECOLA and she even asked for exemption from paying them.

The Court of Appeals found that, indeed, Elena admitted that respondents were not paid their ECOLA and that she

asked for exemption from doing so.107 In addition, Elenas allegations of payment of the other monetary claims, such

as 13th month pay, holiday pay, and premium for holiday pay, were not supported by substantial evidence.108

A review of the records reveals that even if the Court of Appeals considered the vouchers marked as Annexes 7 to

74 and submitted by Elena, these would only disprove her claim of payment.

Annexes 7 to 74109 are vouchers showing payment of holiday pay, 13th month pay, and service incentive leave pay

to respondents. However, not all vouchers were signed by them. Further, in some of the vouchers, the amount given

to respondents was not written. Hence, these vouchers do not prove Elena's claim of payment.

As to the award of money claims, including moral and exemplary damages, Elena argued that respondents did not

present evidence to prove their entitlement to damages.110

Considering the circumstances surrounding respondents' dismissal, the Court of Appeals did not err in upholding the

Labor Arbiter's award of moral and exemplary damages. Indeed, there was malice when, as a retaliatory measure,

petitioners dismissed respondents because they filed a labor complaint. Further, Elena violated respondents' rights

to substantive and procedural due process when she failed to issue notices to explain and notices of termination.

Gone are the days when workers were reduced to mendicant despondency by their employers. Within our legal

order, workers have legal rights and procedures to claim these rights. The only way for employers to avoid legal

action from their workers is to give them what they may be due in law and.as human beings. Businesses thrive

through the acumen of their owners and entrepreneurs. But, none of them will exist without the outcome of the

sacrifices and toil of their workers. Our economy thrives through this partnership based upon mutual respect. At the

very least, these are the values which are congealed in our present laws.

1wphi1

Apparently, in this case, the owners forgot that labor is not merely a factor of production. It is a human product no

matter how modest it may seem to them.

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the Court of Appeals' decision dated July 28, 2009, and its resolution dated

November 27, 2009, reinstating the Labor Arbiter's decision dated August 2, 2006, are hereby AFFIRMED.

SO ORDERED.

MARVIC M.V.F. LEONEN

Associate Justice

WE CONCUR:

ANTONIO T. CARPIO

Associate Justice

Chairperson

MARIANO C. DEL CASTILLO

Associate Justice

JOSE CATRAL MENDOZA

Associate Justice

BIENVENIDO L. REYES*

Associate Justice

ATTESTATION

I attest that the conclusions in the above Decision had been reached in consultation before the case was assigned

to the writer of the opinion of the Court's Division.

ANTONIO T. CARPIO

Associate Justice

Chairperson, Second Division

CERTIFICATION

http://www.lawphil.net/judjuris/juri2014/nov2014/gr_190486_2014.html

Page 9 of 14

G.R. No. 190486

8/31/15 10:21 PM

Pursuant to Section 13, Article VIII of the Constitution and the Division Chairperson's Attestation, I certify that the

conclusions in the above Decision had been reached in consultation before the case was assigned to the writer of

the opinion of the Court's Division.

MARIA LOURDES P.A. SERENO

Chief Justice

Footnotes

*

Designated Acting Member per Special Order No. 1881 dated November 25, 2014.

Rollo, pp. 7-35.

Id. at 3, 7, 9, 270 and 89. The motion for extension of time to file petition for review on certiorari was filed by

Stanley Fine Furniture, Elena and Carlos Wang. The petition for review was filed by Elena Briones. In the

statement of facts, Elena alleged that she "is the registered owner/proprietress of the business operation

doing business under the name and style 'Stanley Fine Furniture." The Department of Trade and Industry

certification attached to the reply states that Stanley Fine Furniture is a sole proprietorship owned by Elena

Briones Yam-Wang. In the amended complaint, filed at the National Labor Relations Commission,

complainants Victor Galiano and Enriquito Siarez indicated 'Stanley Fine Furniture, Elena Briones Wang as

owner & Carlos Wang' as the respondents. Thus, Elena Briones, Elena Briones Wang, and Elena Briones

Yam-Wang refer to the same person. For this decision, we refer to petitioner as Elena Briones.

3

Id. at 3847. The decision was penned by Associate Justice FernandaLampas Peralta and concurred in by

Associate Justices Andres B. Reyes, Jr. (Chair) and Apolinario D. Bruselas, Jr.

4

Id. at 46.

Id. at 39.

Id. at 88.

Id.

Id. at 89.

Id.

10

Id. at 39.

11

Id.

12

Id. at 161166.

13

Id. at 162164.

14

Id. at 164.

15

Id. at 165.

16

Id. at 7177.

17

Id. at 73 and 75.

18

Id. at 7576.

19

Id. at 7884.

20

Id. at 8687.

21

Id. at 43.

http://www.lawphil.net/judjuris/juri2014/nov2014/gr_190486_2014.html

Page 10 of 14

G.R. No. 190486

8/31/15 10:21 PM

21

Id. at 43.

22

Id.

23

Id.

24

Id.

25

Id. at 44,citing Mattel, Inc. v. Francisco, et al., 582 Phil. 492, 500 (2008) [Per J. Austria-Martinez, Third

Division] and Heirs of Miguel Franco v. Court of Appeals, 463 Phil. 417, 428 (2003) [Per J. Tinga, Second

Division].

26

Rollo, p. 44.

27

Id. at 45.

28

Id. at 46.

29

Id.

30

Id. at 5055.

31

Id. at 49.

32

Id. at 34.

33

Id. at 7.

34

Id. at 9.

35

Id. at 27.

36

Id. at 162.

37

Id. at 28.

38

Id. at 24.

39

Id. at 31.

40

Id. at 32.

41

Id. at 178.

42

Id. at 189205.

43

Id. at 190.

44

Id. at 194.

45

Id. at 191.

46

Id. at 262269.

47

Id. at 263.

48

Id. at 271.

49

Id. at 270.

50

Id. at 190191.

51

Id. at 263.

http://www.lawphil.net/judjuris/juri2014/nov2014/gr_190486_2014.html

Page 11 of 14

G.R. No. 190486

8/31/15 10:21 PM

51

Id. at 263.

52

Id. at 262.

53

Id. at 89.

54

598 Phil. 94 (2009) [Per J. Tinga, Second Division].

55

Id. at 101, citing Mangila v. Court of Appeals, 435 Phil. 870, 886 (2002) [Per J. Carpio, Third Division].

56

Rollo, p. 24.

57

Id.

58

Id.

59

Id.

60

J. Brion, dissenting opinion in Abbot Laboratories, Phils., v. Pearlie Ann F. Alcaraz,G.R. No. 192571, April

22,

2014

<http://sc.judiciary.gov.ph/pdf/web/viewer.html?file=/jurisprudence/

2014/april2014/192571_brion.pdf> [Per J. Perlas-Bernabe, En Banc].

61

Rollo, p. 43.

62

Id. at 27.

63

Pres. Decree No. 442 (1974), as amended by Pres. Decree Nos. 570-A, 626, 643, 823, 849, 850, 865-A,

891, 1083, 1367, 1368, 1391, 1412, 1641, 1691, 1692, 1693, 1920, 1921, and 2018; Batas Blg. 32, 70, 130,

and 227; Exec. Order Nos. 74, 111, 126, 180, 203, 247, 251, 292, and 797; Rep. Act Nos. 6715, 6725, 6727,

7610, 7641, 7655, 7658, 7700, 7730, 7796, 7877, 8042, and 9177, arts. 282, 283, 284, and 285.

64

Galang v. Malasugui, G.R. No. 174173, March 7, 2012, 667 SCRA 622, 633 [Per J. Perez, Second

Division].

65

Josan, JPS, Santiago Cargo Movers v. Aduna, G.R. No. 190794, February 22, 2012, 666 SCRA 679, 686

[Per J. Sereno (now C.J.), Second Division]. See also E.G. & I. Construction Corporation v. Sato, G.R. No.

182070, February 16, 2011, 643 SCRA 492, 499500 [Per J. Nachura, Second Division]; and Dimagan v.

Dacworks United, Incorporated, G.R. No. 191053, November 28, 2011, 661 SCRA 438, 447 [Per J. PerlasBernabe, Third Division].

66

491 Phil. 434 (2005) [Per J. Sandoval-Gutierrez, Third Division].

67

Id. at 439, citing Samarca v. Arc-Men Industries, Inc., 459 Phil. 506, 515 (2003) [Per J. Sandoval-Gutierrez,

Third Division].

68

Rollo, p. 44.

69

Id.

70

Id. at 43.

71

Samar-Med Distribution v. NLRC, G.R. No. 162385, July 15, 2013, 701 SCRA 148, 160 [Per J. Bersamin,

First Division].

72

Rollo, p. 99.

73

Id. at 28.

74

Id. at 266.

75

Id. at 9097.

76

Id. at 90.

http://www.lawphil.net/judjuris/juri2014/nov2014/gr_190486_2014.html

Page 12 of 14

G.R. No. 190486

8/31/15 10:21 PM

77

Id. at 91.

78

Id. at 146148.

79

Id. at 147.

80

Id. at 74.

81

Id. at 75.

82

Id. at 44,citing Mattel, Inc. v. Francisco, et al., 582 Phil. 492, 500 (2008) [Per J. Austria-Martinez, Third

Division] and Heirs of Miguel Franco v. Court of Appeals, 463 Phil. 417, 428 (2003) [Per J. Tinga, Second

Division].

83

G.R. No. 198357, December 10, 2012, 687 SCRA 643 [Per J. Peralta, Third Division].

84

Id. at 648.

85

Rollo, p. 27.

86

Id. at 29.

87

Id. at 30.

88

Id.

89

553 Phil. 108 (2007) [Per J. Velasco, Jr., Second Division].

90

Id. at 115116.

91

Rollo, p. 31.

92

496 Phil. 421 (2005) [Per J. Corona, Third Division].

93

Rollo, p. 31.

94

Lee v. Regional Trial Court of Quezon City, Br. 85, 496 Phil. 421, 426427 (2005) [Per J. Corona, Third

Division].

95

Id. at 425426.

96

Rollo, p. 45.

97

Id. at 103107.

98

Id. at 104.

99

Id. at 105.

100

Id. at 106.

101

Id. at 107.

102

Id. at 89. This is the date of dismissal written in the complaint form.

103

Id. at 103.

104

In the Labor Arbiters decision, the following monetary awards were granted: backwages, 13th month pay,

service incentive leave pay, ECOLA, moral damages, and exemplary damages.

105

Rollo, p. 46.

106

Id. at 201.

http://www.lawphil.net/judjuris/juri2014/nov2014/gr_190486_2014.html

Page 13 of 14

G.R. No. 190486

8/31/15 10:21 PM

106

Id. at 201.

107

Id. at 45.

108

Id.

109

Id. at 109-143.

110

Id. at 32.

The Lawphil Project - Arellano Law Foundation

http://www.lawphil.net/judjuris/juri2014/nov2014/gr_190486_2014.html

Page 14 of 14

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Supreme Court Eminent Domain Case 09-381 Denied Without OpinionDa EverandSupreme Court Eminent Domain Case 09-381 Denied Without OpinionNessuna valutazione finora

- Labor Review DigestDocumento24 pagineLabor Review DigestNelle Bulos-VenusNessuna valutazione finora

- Stanley Fine V GallanoDocumento2 pagineStanley Fine V GallanoflippchickNessuna valutazione finora

- Memorandum Labor CaseDocumento6 pagineMemorandum Labor CaseTauMu Academic100% (1)

- Case No. 8 (Premium Wash Laundry v. Esguerra)Documento6 pagineCase No. 8 (Premium Wash Laundry v. Esguerra)Ambassador WantedNessuna valutazione finora

- Stanley v. GallanoDocumento3 pagineStanley v. GallanoErikha AranetaNessuna valutazione finora

- International Human Resource ManagementDocumento42 pagineInternational Human Resource Managementnazmulsiad200767% (3)

- Reflective Essay - Pestle Mortar Clothing BusinessDocumento7 pagineReflective Essay - Pestle Mortar Clothing Businessapi-239739146Nessuna valutazione finora

- Advanced Strategic ManagementDocumento97 pagineAdvanced Strategic Managementsajidrasool55Nessuna valutazione finora

- Insurance CompaniesDocumento59 pagineInsurance CompaniesParag PenkerNessuna valutazione finora

- Imasen Phils Vs AlconDocumento6 pagineImasen Phils Vs AlconkhailcalebNessuna valutazione finora

- Best Evidence Rule CasesDocumento6 pagineBest Evidence Rule Casescharmagne cuevasNessuna valutazione finora

- Petition For Certiorati (Del Fiero-Juan vs. NLRC)Documento26 paginePetition For Certiorati (Del Fiero-Juan vs. NLRC)Nathaniel Torres100% (1)

- Imasen Philippine Sex Act RulingDocumento6 pagineImasen Philippine Sex Act RulingDane Anthony BibarNessuna valutazione finora

- Investment DecisionsDocumento39 pagineInvestment DecisionsQwertyNessuna valutazione finora

- Advanced Accounting Fischer11e - SMChap21Documento24 pagineAdvanced Accounting Fischer11e - SMChap21sellertbsm2014Nessuna valutazione finora

- Demand Management: Leading Global Excellence in Procurement and SupplyDocumento7 pagineDemand Management: Leading Global Excellence in Procurement and SupplyAsif Abdullah ChowdhuryNessuna valutazione finora

- Demand To Cease and DesistDocumento1 paginaDemand To Cease and DesistGerard Nelson ManaloNessuna valutazione finora

- Godrej Case StudyDocumento2 pagineGodrej Case StudyMeghana PottabathiniNessuna valutazione finora

- Eir January2018Documento1.071 pagineEir January2018AbhishekNessuna valutazione finora

- MARIA VILMA G. DOCTOR AND JAIME LAO, JR. vs. NII ENTERPRISES AND/OR MRS. NILDA C. IGNACIO G.R. No. 194001, November 22, 2017Documento3 pagineMARIA VILMA G. DOCTOR AND JAIME LAO, JR. vs. NII ENTERPRISES AND/OR MRS. NILDA C. IGNACIO G.R. No. 194001, November 22, 2017Lau NunezNessuna valutazione finora

- Datu Samad Mangelen Vs CADocumento8 pagineDatu Samad Mangelen Vs CASherimar BongdoenNessuna valutazione finora

- CASES Set 2 Personal DigestDocumento76 pagineCASES Set 2 Personal DigestAngelie AbangNessuna valutazione finora

- G.R. No.190486 November 26, 2014 Stanley Fine Furniture, Elenaand Carlos Wang, Petitioners, Victor T. Gallano and Enriquito Siarez, RespondentsDocumento17 pagineG.R. No.190486 November 26, 2014 Stanley Fine Furniture, Elenaand Carlos Wang, Petitioners, Victor T. Gallano and Enriquito Siarez, RespondentsMikkaEllaAnclaNessuna valutazione finora

- G.R. No.190486 November 26, 2014 Stanley Fine Furniture, Elenaand Carlos Wang, Petitioners, Victor T. Gallano and Enriquito Siarez, RespondentsDocumento66 pagineG.R. No.190486 November 26, 2014 Stanley Fine Furniture, Elenaand Carlos Wang, Petitioners, Victor T. Gallano and Enriquito Siarez, RespondentsNicole Ann Delos ReyesNessuna valutazione finora

- Court of Appeals Reverses NLRC Ruling on Illegal DismissalDocumento9 pagineCourt of Appeals Reverses NLRC Ruling on Illegal DismissalRoseann BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Republic of The Philippines Supreme Court: ManilaDocumento8 pagineRepublic of The Philippines Supreme Court: Manila'Naif Sampaco PimpingNessuna valutazione finora

- The Respondents Neither Filed Any Position Paper Nor Proffered Pieces of Evidence in Their Defense Despite Their Knowledge of The Pendency of The CaseDocumento8 pagineThe Respondents Neither Filed Any Position Paper Nor Proffered Pieces of Evidence in Their Defense Despite Their Knowledge of The Pendency of The Caseyangkee_17Nessuna valutazione finora

- Metro Transit Organization, Inc. vs. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 142133, November 19, 2002Documento10 pagineMetro Transit Organization, Inc. vs. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 142133, November 19, 2002jonbelzaNessuna valutazione finora

- G.R. No. 191825Documento13 pagineG.R. No. 191825Farahleen Pearl PalacNessuna valutazione finora

- Nagkakaisang Lakas v. KeihinDocumento9 pagineNagkakaisang Lakas v. KeihinAyet RamosNessuna valutazione finora

- Nagkakaisang Lakas NG Manggagawa Sa Keihin v. Keihin PhilDocumento6 pagineNagkakaisang Lakas NG Manggagawa Sa Keihin v. Keihin PhilImelda Arreglo-AgripaNessuna valutazione finora

- Sereneo Labor Dispute Ruling UpheldDocumento3 pagineSereneo Labor Dispute Ruling Upheldgemmo_fernandezNessuna valutazione finora

- Court Rules on Defective Verification in Labor CaseDocumento8 pagineCourt Rules on Defective Verification in Labor CaseIan Aguihap ResentesNessuna valutazione finora

- Petitioner Vs VS: Second DivisionDocumento7 paginePetitioner Vs VS: Second DivisiontheresagriggsNessuna valutazione finora

- Digest 1-5cDocumento14 pagineDigest 1-5cDee SantosNessuna valutazione finora

- DJIC and Ferraris v. RañesesDocumento9 pagineDJIC and Ferraris v. RañesesAraveug InnavoigNessuna valutazione finora

- Kanlaon Construction Ent. vs. NLRC, 87 SCAD 196, 279 SCRA 326 (1997)Documento6 pagineKanlaon Construction Ent. vs. NLRC, 87 SCAD 196, 279 SCRA 326 (1997)Jellie Grace CañeteNessuna valutazione finora

- Marmosy Trading Vs CADocumento8 pagineMarmosy Trading Vs CAEricson Sarmiento Dela CruzNessuna valutazione finora

- Dimagan Vs Dacworks UnitedDocumento10 pagineDimagan Vs Dacworks UnitedJanin GallanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Evidence Case DigestDocumento3 pagineEvidence Case DigestNin JaNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 Dee Jay's Inn V Rañeses 2016 AbandonmentDocumento40 pagine1 Dee Jay's Inn V Rañeses 2016 AbandonmentJan Igor GalinatoNessuna valutazione finora

- Kanlaon Construction Vs NLRCDocumento11 pagineKanlaon Construction Vs NLRCMark Paul CortejosNessuna valutazione finora

- Quillosa Vs SJ Gas - MRDocumento5 pagineQuillosa Vs SJ Gas - MRGerald HernandezNessuna valutazione finora

- NLRC CaseDocumento4 pagineNLRC CaseJyp Phyllis GalanNessuna valutazione finora

- Sereneo vs. Schering Plough, Corp G.R. No. 142506 - February 17, 2005Documento4 pagineSereneo vs. Schering Plough, Corp G.R. No. 142506 - February 17, 2005ELMER T. SARABIANessuna valutazione finora

- One Shipping Vs PenafielDocumento7 pagineOne Shipping Vs PenafielJohn Wick F. GeminiNessuna valutazione finora

- Court upholds dismissal of supervisors who covered up drunk driving incidentDocumento4 pagineCourt upholds dismissal of supervisors who covered up drunk driving incidenttynajoydelossantosNessuna valutazione finora

- Bughaw Vs Treasure IslandDocumento11 pagineBughaw Vs Treasure IslandCeline Sayson BagasbasNessuna valutazione finora

- G.R. No. 186621 March 12, 2014 South East International Rattan, Inc. And/Or Estanislao AGBAY, Petitioners, JESUS J. COMING, RespondentDocumento7 pagineG.R. No. 186621 March 12, 2014 South East International Rattan, Inc. And/Or Estanislao AGBAY, Petitioners, JESUS J. COMING, RespondentKimberly Sheen Quisado TabadaNessuna valutazione finora

- G.R. No. 167751 HAPOON MARINE ROSIT VS FRANCISCO 1Documento3 pagineG.R. No. 167751 HAPOON MARINE ROSIT VS FRANCISCO 1Zainne Sarip BandingNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Title: Ester M. Asuncion, Petitioner, vs. National Labor Relations CommissionDocumento13 pagineCase Title: Ester M. Asuncion, Petitioner, vs. National Labor Relations CommissiongeorjalynjoyNessuna valutazione finora

- BP 22 - Prescription of 10 YearsDocumento10 pagineBP 22 - Prescription of 10 YearsJohn Wick F. GeminiNessuna valutazione finora

- Philippines Supreme Court rules on teacher dismissalsDocumento5 paginePhilippines Supreme Court rules on teacher dismissalsVenn Bacus RabadonNessuna valutazione finora

- Enrile vs. Hon. ManalastasDocumento6 pagineEnrile vs. Hon. ManalastasjieNessuna valutazione finora

- G.R. No. 175481 November 21, 2012Documento18 pagineG.R. No. 175481 November 21, 2012Angelica Sabben MaribbayNessuna valutazione finora

- CaseDocumento93 pagineCaseRock StoneNessuna valutazione finora

- Court Reviews Liability of Staffing Agency for Damages Caused by Employee StrikeDocumento5 pagineCourt Reviews Liability of Staffing Agency for Damages Caused by Employee StrikeDenzhu MarcuNessuna valutazione finora

- 28 Harpoon Marine Services, Inc., Et Al. v. Fernan H. Francisco, G.R. No. 167751, March 2, 2011Documento7 pagine28 Harpoon Marine Services, Inc., Et Al. v. Fernan H. Francisco, G.R. No. 167751, March 2, 2011AlexandraSoledadNessuna valutazione finora

- HSBC v. NLRCDocumento3 pagineHSBC v. NLRCTJ CortezNessuna valutazione finora

- Labor Dispute Ruling Overturned Due to Lack of JurisdictionDocumento5 pagineLabor Dispute Ruling Overturned Due to Lack of JurisdictionAnn ChanNessuna valutazione finora

- Court upholds criminal charges against corporate officers for refusing stockholder access to recordsDocumento7 pagineCourt upholds criminal charges against corporate officers for refusing stockholder access to recordsRonnel FilioNessuna valutazione finora

- Encashment of CheckDocumento17 pagineEncashment of CheckmjNessuna valutazione finora

- Wills Cases - Balane (Set 1)Documento44 pagineWills Cases - Balane (Set 1)Alfarah Alonto AdiongNessuna valutazione finora

- Enrile VS Manalastas GR No. 166414 Oct 22 2014Documento9 pagineEnrile VS Manalastas GR No. 166414 Oct 22 2014Maricel DefelesNessuna valutazione finora

- 10 Wenphil Corporation Vs Abing and TuazonDocumento10 pagine10 Wenphil Corporation Vs Abing and TuazonMCNessuna valutazione finora

- Dee Jay's Inn and Cafe or Melinda Ferraris v. Ma. Lorina Raneses G.R. No. 191825, 5 October 2016Documento13 pagineDee Jay's Inn and Cafe or Melinda Ferraris v. Ma. Lorina Raneses G.R. No. 191825, 5 October 2016bentley CobyNessuna valutazione finora

- G.R. No. 189255 June 17, 2015 JESUS G. REYES, Petitioner, Glaucoma Research Foundation, Inc., Eye Referral Center and Manuel B. AGULTO, RespondentsDocumento6 pagineG.R. No. 189255 June 17, 2015 JESUS G. REYES, Petitioner, Glaucoma Research Foundation, Inc., Eye Referral Center and Manuel B. AGULTO, RespondentsKimberly Sheen Quisado TabadaNessuna valutazione finora

- U.S. v. Sun Myung Moon 532 F.Supp. 1360 (1982)Da EverandU.S. v. Sun Myung Moon 532 F.Supp. 1360 (1982)Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lopez vs. MWSS p5Documento1 paginaLopez vs. MWSS p5Anonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- Lopez vs. MWSS (Dragged) PDFDocumento1 paginaLopez vs. MWSS (Dragged) PDFAnonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- Lopez vs. MWSS p4Documento1 paginaLopez vs. MWSS p4Anonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- Lopez vs. MWSS SyllabusDocumento5 pagineLopez vs. MWSS SyllabusAnonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- Lopez vs. MWSS (Dragged) PDFDocumento1 paginaLopez vs. MWSS (Dragged) PDFAnonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- Lopez vs. MWSS (Dragged) PDFDocumento1 paginaLopez vs. MWSS (Dragged) PDFAnonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- Lopez vs. Metropolitan Waterworks and Sewerage SystemDocumento1 paginaLopez vs. Metropolitan Waterworks and Sewerage SystemAnonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- Lopez vs. MWSSDocumento26 pagineLopez vs. MWSSAnonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- Drilon vs. CA p2Documento1 paginaDrilon vs. CA p2Anonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- Que vs. IACDocumento1 paginaQue vs. IACAnonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- Lopez vs. MWSS SyllabusDocumento5 pagineLopez vs. MWSS SyllabusAnonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- Drilon vs. CA p4Documento1 paginaDrilon vs. CA p4Anonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- Drilon vs. CA p1Documento1 paginaDrilon vs. CA p1Anonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- Lopez vs. MWSSDocumento26 pagineLopez vs. MWSSAnonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- Supreme Court Reports Annotated Volume 515 Malicious Prosecution ElementsDocumento1 paginaSupreme Court Reports Annotated Volume 515 Malicious Prosecution ElementsAnonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- Hemedes vs. CA p24Documento1 paginaHemedes vs. CA p24Anonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- Supreme Court Rules on Malicious Prosecution CaseDocumento1 paginaSupreme Court Rules on Malicious Prosecution CaseAnonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- Drilon vs. CA p1Documento1 paginaDrilon vs. CA p1Anonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- Hemedes vs. CA p23Documento1 paginaHemedes vs. CA p23Anonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- Drilon vs. CADocumento12 pagineDrilon vs. CAAnonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- NSTW Davao 04july2017 Handout Copy (Dragged)Documento1 paginaNSTW Davao 04july2017 Handout Copy (Dragged)Anonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- Hemedes vs. CA p42Documento1 paginaHemedes vs. CA p42Anonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- Hemedes vs. CA CrossDocumento2 pagineHemedes vs. CA CrossAnonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- Acad Cal 2017-2018 PDFDocumento1 paginaAcad Cal 2017-2018 PDFAnonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- Hemedes vs. CA p21Documento1 paginaHemedes vs. CA p21Anonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- Hemedes vs. CA p23Documento1 paginaHemedes vs. CA p23Anonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- Hemedes vs. CA p25Documento1 paginaHemedes vs. CA p25Anonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- Hemedes vs. CA p42Documento1 paginaHemedes vs. CA p42Anonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- Hemedes vs. CA p41Documento2 pagineHemedes vs. CA p41Anonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- Hemedes vs. CA p8Documento1 paginaHemedes vs. CA p8Anonymous nYvtSgoQNessuna valutazione finora

- Jurnal RisvanDocumento10 pagineJurnal Risvanfapertaung01Nessuna valutazione finora

- Braun - AG - Group 2 SEC BDocumento33 pagineBraun - AG - Group 2 SEC BSuraj KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Evotech Case Study 3D Printed Bike Frame PDFDocumento2 pagineEvotech Case Study 3D Printed Bike Frame PDFThe DNessuna valutazione finora

- Multiple Choice CH 2Documento5 pagineMultiple Choice CH 2gotax100% (3)

- Merits and DemeritsDocumento2 pagineMerits and Demeritssyeda zee100% (1)

- Balance Sheet Analysis FY 2017-18Documento1 paginaBalance Sheet Analysis FY 2017-18AINDRILA BERA100% (1)

- Modern Systems Analysis and Design: The Sources of SoftwareDocumento39 pagineModern Systems Analysis and Design: The Sources of SoftwareNoratikah JaharudinNessuna valutazione finora

- Entrepreneurship and Enterprise Development Final ExamDocumento3 pagineEntrepreneurship and Enterprise Development Final ExammelakuNessuna valutazione finora

- A Study On Risk and Return Analysis of Listed Stocks in Sensex With Special Reference To Bombay Stock ExchangeDocumento83 pagineA Study On Risk and Return Analysis of Listed Stocks in Sensex With Special Reference To Bombay Stock ExchangeVRameshram50% (8)

- TRACKING#:89761187821: BluedartDocumento2 pagineTRACKING#:89761187821: BluedartStone ColdNessuna valutazione finora

- (En) 7-Wonders-Cities-RulebookDocumento12 pagine(En) 7-Wonders-Cities-RulebookAntNessuna valutazione finora

- Business Summit Proposal 2019Documento5 pagineBusiness Summit Proposal 2019Geraldine Pajudpod100% (1)

- Suvarna Paravanige - Sanction of Building Plan in a Sital AreaDocumento1 paginaSuvarna Paravanige - Sanction of Building Plan in a Sital AreaareddappaNessuna valutazione finora

- Philippine Government Electronic Procurement System GuideDocumento11 paginePhilippine Government Electronic Procurement System GuideDustin FormalejoNessuna valutazione finora

- ERC Non-Conformance Corrective ProcedureDocumento13 pagineERC Non-Conformance Corrective ProcedureAmanuelGirmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Shankara Building Products Ltd-Mumbai Registered Office at Mumbai GSTIN Number: 27AACCS9670B1ZADocumento1 paginaShankara Building Products Ltd-Mumbai Registered Office at Mumbai GSTIN Number: 27AACCS9670B1ZAfernandes_j1Nessuna valutazione finora

- Materi PDFDocumento19 pagineMateri PDFUlyviatrisnaNessuna valutazione finora

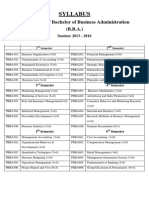

- BBA Syllabus 2013-2016Documento59 pagineBBA Syllabus 2013-2016GauravsNessuna valutazione finora

- Business Practices of CommunitiesDocumento11 pagineBusiness Practices of CommunitiesKanishk VermaNessuna valutazione finora

- ImagePRESS C850 C750 Brochure MDocumento12 pagineImagePRESS C850 C750 Brochure MSanjay ArmarkarNessuna valutazione finora