Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Performance Evaluation

Caricato da

theateeqCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Performance Evaluation

Caricato da

theateeqCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Q3

Performance Evaluation

Performance evaluation is a strategic human resources management tool that organizations

should be using on a regular basis to determine what types of skills, knowledge and

characteristics are currently available in the organization. It is a method through which the

organization can obtain information that will be needed when making decisions about

employee advancement, retention and separation (Pynes, 1997). In making such decisions it

is vital that organizations review job performance in a way that benefits both the organization

and the employee. Through performance evaluation, an organization can provide the

feedback to employees that is necessary if employees are going to improve job performance,

strengthen employee-supervisor relationships, and maintain organization-wide morale. As

Craig R. Stevens (1996) remarks, “How well your organization measures and monitors job

performance is crucial not only to the competitiveness of the organization, but also to

employee productivity”.

Executive directors of nonprofit organizations are usually evaluated by the board of directors

or the personnel committee. The purpose of evaluating the executive director should be to

improve the way the organization is managed. To this end, executive directors should be told

in advance what issues and areas the board will be looking at when it does the evaluation,

and they should be given an opportunity to prepare a self-evaluation as well. A performance

evaluation of a management executive works strategically and benefits both the organization

and the executive when it serves to help the executive become aware of his/her strengths

and weaknesses and improve his/her job performance. The performance evaluation of a

management executive can take on a hostile tone, full of recriminations and criticisms,

especially if the evaluation takes place around the time of contract renewal. Rather than

serving as an exercise that increases tension and hostility, the performance evaluation of an

executive should be looked at as an opportunity for the board and the executive to strengthen

the organization by resolving any differences they might have regarding their roles and

responsibilities (Pynes, 1997).

Synagogues, like other organizations, should conduct performance evaluations of their

executives, the rabbi and executive director, on a regular basis. Due to the community

nature of the synagogue and the “spiritual leader” or “Symbolic Exemplar” position of the

rabbi, it is especially important that these performance evaluations are carried out in such a

way as to improve the relationship between the rabbi or executive director and the

congregation. As Rabbi Bloom (2002) notes, “other people are…valued in terms of what they

do. The rabbi is valued in terms of who he is perceived to be”. The Reconstructionist

Commission on the Role of the Rabbi (2001) remarks, “Evaluation can provide a continuous

loop in which successes are celebrated, mistakes identified, progress noted, tasks reviewed

and problems resolved”.

Evaluations of synagogue executive directors have become a common practice in modern

synagogues. Iris P. Henley (1997)) points out that “executive directors are in a unique

predicament, commanded to serve as well as lead” (p. 18), and therefore it is frequently not

clear who is the supervisor of the executive director and who should be conducting the

performance evaluation. Henley recommends that the synagogue establish a personnel

committee, and that each professional staff member be assigned a liaison from the personnel

committee. The liaison would take responsibility for reporting to the personnel committee any

issues or problems that arise with that staff member, and the liaison would conduct

performance evaluations of the staff member, with input from those who have regular contact

and interaction with that person. Henley advises synagogues and executive directors to

remember that while every nonprofit organization should use executive evaluation to improve

job performance and develop careers, synagogues have an even more important reason for

doing so, because their executives are Jewish professionals who are working for the “health

and well being of Judaism” (p. 17).

Despite the “unique predicament” of synagogue executive directors as both leaders,

followers, and Jewish professionals, it is not difficult for boards of directors and personnel

committees to place the executive director in a performance evaluation process that is

familiar from other organizations, both nonprofit and for-profit. Evaluating the rabbi, however,

brings up many more complicated issues and problems, and for this reason it is frequently

just not done, or it is done in such a way as to cause harm to the congregation-rabbi

relationship.

Traditionally, the rabbi was the spiritual leader of the community. He provided moral

guidance and taught Jewish values. As Jill Davidson Sklar (2001) points out, because some

synagogues today are beginning to adopt a corporate model of structure and behavior, one of

the important questions being asked by many synagogues is whether the rabbi is the spiritual

leader, the chief executive officer, or both. This is an important question because as Rabbi

Sam Joseph, professor of Jewish religious education at Hebrew Union College points out, “If

you move into formal evaluation systems…then the rabbi is put on more of a corporate

track…That is a double-edged sword. If you start to use the symbols of business, you will be

treated as a business and CEOs are fired” (qtd.in Sklar, p. 41). Treating the rabbi as CEO

may not lead to firing him/her in every case, but as Rabbi Allen I. Freehling (2002), Rabbi

Emeritus of University Synagogue in Los Angeles, has observed, it can cause serious

damage to the rabbi-congregation relationship. Rabbi Freehling remarks, “Under these

circumstances the contemporary Reform rabbi has come to be identified by many or even all

congregation members as just another one of the synagogue’s professional staff – just

another employee who is no different than everyone else listed in the personnel roster. This

is detrimental not only to the rabbi, but also to most congregants who eagerly look up to or

would like to look up to their Rabbi as a special person in their lives” (p. 21-22).

The Reconstructionist Commission on the Role of the Rabbi (2001) recommends that

synagogues avoid following the corporate model when evaluating the rabbi. They suggest

that an evaluation should be done that focuses “on how the entire congregational community

is fulfilling its goals, mission and vision”(p. 71). The rabbi could then be evaluated as part of

that larger evaluation process, along with synagogue leaders, board members, committee

chairs and other staff.

Rabbi Joseph, Rabbi Freehling, and other commentators have noted that it is important to

keep Jewish values in mind when operating a synagogue and when establishing relationships

between the professionals and the lay people. They remind us that, as Jill Davidson Sklar

(2001) remarks, relationships in synagogues should be built on trust, not on the “cutthroat

tactics seen in the secular corporate world” (p. 41).

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Enhancing 360-Degree Feedback for Senior Executives: How to Maximize the Benefits and Minimize the RisksDa EverandEnhancing 360-Degree Feedback for Senior Executives: How to Maximize the Benefits and Minimize the RisksValutazione: 1 su 5 stelle1/5 (1)

- PAF ModelDocumento4 paginePAF Modelarunrad100% (1)

- Quality ChartsDocumento21 pagineQuality ChartsSivakumar BalaNessuna valutazione finora

- QUALITY CONTROLDocumento23 pagineQUALITY CONTROLPrithiviraj RajasekarNessuna valutazione finora

- A Study of Consumer BehaviorDocumento17 pagineA Study of Consumer BehaviorAnkitGhildiyalNessuna valutazione finora

- GE2022 Total Quality Management PDFDocumento132 pagineGE2022 Total Quality Management PDFYash JainNessuna valutazione finora

- BP Mapping I WorkshopDocumento29 pagineBP Mapping I WorkshopJohn RockNessuna valutazione finora

- Evolution of Quality ConceptsDocumento25 pagineEvolution of Quality ConceptsYiğit IlgazNessuna valutazione finora

- Juran's Quality Trilogy: Planning, Control, and ImprovementDocumento2 pagineJuran's Quality Trilogy: Planning, Control, and ImprovementSuhail KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- SAMPLE Onboarding Workgroup ReportDocumento42 pagineSAMPLE Onboarding Workgroup ReportPradyot PriyadarshanNessuna valutazione finora

- Post Implementation Report - GuideDocumento7 paginePost Implementation Report - GuideGuevarraWellrho0% (1)

- Quality Management ProcessDocumento13 pagineQuality Management ProcessSukumar ReddyNessuna valutazione finora

- Sustaining Success " Yash"Documento30 pagineSustaining Success " Yash"Kavya SaxenaNessuna valutazione finora

- 7 Kaizen Tools For AdministratorDocumento201 pagine7 Kaizen Tools For AdministratorazmityNessuna valutazione finora

- Quality Philosophy & Management EssentialsDocumento41 pagineQuality Philosophy & Management EssentialsiJordanScribdNessuna valutazione finora

- Eight Disciplines Problem Solving MethodDocumento4 pagineEight Disciplines Problem Solving MethodAndraNessuna valutazione finora

- The ISO 31 000 Standard On Risk Management: Eric MarsdenDocumento43 pagineThe ISO 31 000 Standard On Risk Management: Eric Marsdensitaram75Nessuna valutazione finora

- Green Belt Body of KnowledgeDocumento4 pagineGreen Belt Body of KnowledgeAlba Marina TorresNessuna valutazione finora

- 2007 - 05 PDI Lean Six SigmaDocumento14 pagine2007 - 05 PDI Lean Six Sigmamandu786Nessuna valutazione finora

- FST 151 Food Freezing CourseDocumento67 pagineFST 151 Food Freezing CourseNamratha100% (1)

- Productivity Improvement Measures and Quality ManagementDocumento62 pagineProductivity Improvement Measures and Quality ManagementWalter RoblesNessuna valutazione finora

- Green RCA Mini Guide v5 Small - UnlockedDocumento15 pagineGreen RCA Mini Guide v5 Small - Unlockedmostafa_1000Nessuna valutazione finora

- TQM Case Study 1Documento1 paginaTQM Case Study 1mathew007100% (3)

- Best Practice Quality Policy StatementsDocumento3 pagineBest Practice Quality Policy StatementsRob WillestoneNessuna valutazione finora

- SIPOCDocumento27 pagineSIPOCEliot JuarezNessuna valutazione finora

- 5.audit Quality Indicators - Perceptions of Junior-Level AuditorsDocumento33 pagine5.audit Quality Indicators - Perceptions of Junior-Level AuditorsDhyartoma Pandhu IskandarNessuna valutazione finora

- Amway Lean Office Hdi 2Documento30 pagineAmway Lean Office Hdi 2Ignacio Guerra100% (1)

- Quality Orientation GuideDocumento25 pagineQuality Orientation GuideAmruthNessuna valutazione finora

- Introducing DMAIC Model With Amazing Examples (Resourceful)Documento12 pagineIntroducing DMAIC Model With Amazing Examples (Resourceful)PraveenNessuna valutazione finora

- Milestone 3 Ogl 357Documento7 pagineMilestone 3 Ogl 357api-688378546Nessuna valutazione finora

- Guide To The Economics of Quality Part 2 Paf ModelDocumento19 pagineGuide To The Economics of Quality Part 2 Paf ModelDavid Camilo Hernandez MayordomoNessuna valutazione finora

- CQP Application Guidance I.IDocumento8 pagineCQP Application Guidance I.IPaul Goh Yngwie0% (1)

- Essential Guide To QMSDocumento24 pagineEssential Guide To QMSMARKASGEORGENessuna valutazione finora

- Basic Quality Control ConceptsDocumento28 pagineBasic Quality Control ConceptsLeeLowersNessuna valutazione finora

- Best Practice Quality Policy StatementsDocumento3 pagineBest Practice Quality Policy StatementsdanielsasikumarNessuna valutazione finora

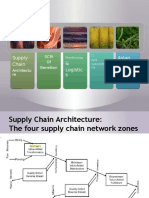

- Supply Chain ManagementDocumento76 pagineSupply Chain Managementsreejith_eimt13Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lean Strategy by Shyam TalawadekarDocumento4 pagineLean Strategy by Shyam Talawadekartsid47Nessuna valutazione finora

- Managing Knowledge Workers ProductivityDocumento25 pagineManaging Knowledge Workers ProductivityDarshan GaragNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Evaluate Your Organization PDFDocumento59 pagineHow To Evaluate Your Organization PDFCoco CandyNessuna valutazione finora

- Green Belt Class NotesDocumento11 pagineGreen Belt Class NotesPankaj LodhiNessuna valutazione finora

- Smith, Gerald - Types of Quality Problems PDFDocumento7 pagineSmith, Gerald - Types of Quality Problems PDFJoana SoaresNessuna valutazione finora

- Customer Satisfaction and Business PerformanceDocumento1 paginaCustomer Satisfaction and Business PerformanceDanyal KhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Audit Training - Evaluating Auditor CompetenceDocumento21 pagineAudit Training - Evaluating Auditor CompetenceAshish TelangNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 15: Statistical Quality ControlDocumento111 pagineChapter 15: Statistical Quality Controljohn brownNessuna valutazione finora

- Kano Model Reliability and ValidityDocumento14 pagineKano Model Reliability and ValidityElmar SauerweinNessuna valutazione finora

- Evolving Role of Finance FinalDocumento12 pagineEvolving Role of Finance FinalVinod HindujaNessuna valutazione finora

- The New Quality ToolsDocumento42 pagineThe New Quality ToolsRavi SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Onboarding Consulting ReportDocumento7 pagineOnboarding Consulting Reportapi-528912912Nessuna valutazione finora

- Understanding Customer ExpectationsDocumento14 pagineUnderstanding Customer Expectationsyashar2500Nessuna valutazione finora

- Total Cost Management Presentation PDFDocumento18 pagineTotal Cost Management Presentation PDFDeejaay2010Nessuna valutazione finora

- CHAPTER 1 - OUTLINE For QUALITY AND PERFORMANCE EXCELLENCEDocumento7 pagineCHAPTER 1 - OUTLINE For QUALITY AND PERFORMANCE EXCELLENCEKenedy FloresNessuna valutazione finora

- BPR Akd FinalDocumento105 pagineBPR Akd FinalNitin CollapenNessuna valutazione finora

- Cap 1004Documento22 pagineCap 1004Dan DumbravescuNessuna valutazione finora

- Supply Chain & Logistic S AsianDocumento9 pagineSupply Chain & Logistic S AsianAmit SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- BCM Risk Matrix GuideDocumento8 pagineBCM Risk Matrix Guidegarry_CNessuna valutazione finora

- Conceptual Foundations of Strategic Planning in The Malcolm Baldrige Criteria For Performance ExcellenceDocumento19 pagineConceptual Foundations of Strategic Planning in The Malcolm Baldrige Criteria For Performance ExcellenceWiddiy Binti KasidiNessuna valutazione finora

- BSC - Balanced Scorecard As Strategic Navigational ChartsDocumento12 pagineBSC - Balanced Scorecard As Strategic Navigational ChartsKristelNessuna valutazione finora

- Quality Management System Process A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionDa EverandQuality Management System Process A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionNessuna valutazione finora

- Transformation Plan A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionDa EverandTransformation Plan A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionNessuna valutazione finora

- Moving Towards Productivity and Quality ExcellenceDa EverandMoving Towards Productivity and Quality ExcellenceNessuna valutazione finora

- Accounting Information SystemDocumento4 pagineAccounting Information SystemtheateeqNessuna valutazione finora

- HRM Q 4Documento2 pagineHRM Q 4theateeqNessuna valutazione finora

- Q-1 Reliability: ValidityDocumento2 pagineQ-1 Reliability: ValiditytheateeqNessuna valutazione finora

- Marketing Management Assignment 1Documento8 pagineMarketing Management Assignment 1theateeqNessuna valutazione finora

- Entrepreneurship Assignment 1Documento15 pagineEntrepreneurship Assignment 1theateeq100% (1)

- Guide To ChatDocumento13 pagineGuide To ChattheateeqNessuna valutazione finora

- Entrepreneurship Assignment 1Documento11 pagineEntrepreneurship Assignment 1theateeq86% (22)

- Cost Solutions Past PapersDocumento22 pagineCost Solutions Past Paperstheateeq100% (1)

- Robert Kiyosaki Michael MaloneyDocumento5 pagineRobert Kiyosaki Michael MaloneyOthman A. MughniNessuna valutazione finora

- Session 9 - Environmental AnalysisDocumento30 pagineSession 9 - Environmental AnalysisJuzlee JM100% (1)

- BS & Going Rate ApprochDocumento2 pagineBS & Going Rate ApprochNiloy ChowdhuryNessuna valutazione finora

- Wyndham Grand HotelDocumento2 pagineWyndham Grand HotelPrashant WaghNessuna valutazione finora

- Teja G SDocumento9 pagineTeja G Sinspire techNessuna valutazione finora

- Budget and Budgetary Control Literature ReviewDocumento7 pagineBudget and Budgetary Control Literature Reviewafmzsprjlerxio100% (1)

- St. Mary's College Preliminary Exam in The Contemporary WorldDocumento5 pagineSt. Mary's College Preliminary Exam in The Contemporary WorldRoessi Mae Abude AratNessuna valutazione finora

- Ashghal OverviewDocumento3 pagineAshghal OverviewrmdarisaNessuna valutazione finora

- Application For Employment: Photo 1" X 1"Documento4 pagineApplication For Employment: Photo 1" X 1"Jinky Mae PobrezaNessuna valutazione finora

- Tqm-Stmicroelectronics Case Study JoseDocumento4 pagineTqm-Stmicroelectronics Case Study JosekringtrezNessuna valutazione finora

- Stress in The WorkplaceDocumento10 pagineStress in The WorkplaceWendyLu32100% (1)

- BBMP INTERIOR WORKS TENDERDocumento40 pagineBBMP INTERIOR WORKS TENDERChethan GowdaNessuna valutazione finora

- Solution Manual For OM 4 4th Edition by CollierDocumento15 pagineSolution Manual For OM 4 4th Edition by CollierNonoyArendainNessuna valutazione finora

- Economic Modelling: Rongsheng Tang, Gaowang WangDocumento20 pagineEconomic Modelling: Rongsheng Tang, Gaowang WangpalupiclaraNessuna valutazione finora

- Concepts of Income, Gross Income, and Compensation IncomeDocumento61 pagineConcepts of Income, Gross Income, and Compensation IncomeMeden Robrigado-LabogNessuna valutazione finora

- Three: © 2019 Mcgraw-Hill Ryerson Education Limited Schwind 12Th Edition 3-1Documento33 pagineThree: © 2019 Mcgraw-Hill Ryerson Education Limited Schwind 12Th Edition 3-1ManayirNessuna valutazione finora

- The Evolution from CSR to Supply Chain ResponsibilityDocumento12 pagineThe Evolution from CSR to Supply Chain ResponsibilityYvonne FangNessuna valutazione finora

- Pragati Chandraprakash Chaudhary - 2 PDFDocumento23 paginePragati Chandraprakash Chaudhary - 2 PDFPawan YadavNessuna valutazione finora

- Gierke - Soziale Aufgabe Des Privatrechts PDFDocumento102 pagineGierke - Soziale Aufgabe Des Privatrechts PDFEugenio Muinelo PazNessuna valutazione finora

- DownsizingDocumento113 pagineDownsizinghr14Nessuna valutazione finora

- 03 - Literature ReviewDocumento7 pagine03 - Literature ReviewVienna Corrine Q. AbucejoNessuna valutazione finora

- Strat 15finalDocumento153 pagineStrat 15finalKowshik ChakrabortyNessuna valutazione finora

- Manpower Planning and HR MetricsDocumento28 pagineManpower Planning and HR MetricsNaveen Thulasidharan50% (2)

- Internal Customer Satisfaction Leads To External Customers SatisfactionDocumento21 pagineInternal Customer Satisfaction Leads To External Customers Satisfactionumerfarooqmba88% (16)

- McGregor's Theory YDocumento13 pagineMcGregor's Theory Ymohammed elshazaliNessuna valutazione finora

- 2014Documento68 pagine2014Talib AbdullahNessuna valutazione finora

- Maternity Leave AdvisoryDocumento3 pagineMaternity Leave AdvisoryEunice DahonogNessuna valutazione finora

- UshaDocumento141 pagineUshaimranjani.skNessuna valutazione finora

- Job Description and Person Specification Finance Manager Aug 2015Documento4 pagineJob Description and Person Specification Finance Manager Aug 2015MinMonica Ranoy SulivaNessuna valutazione finora

- Danfoss - HR Benefit Booklet 2019Documento9 pagineDanfoss - HR Benefit Booklet 2019Sreekanth PCNessuna valutazione finora