Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Fractura de Un Pilar PPF

Caricato da

Carlos NaupariTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Fractura de Un Pilar PPF

Caricato da

Carlos NaupariCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Fracture of a fixed partial denture abutment: A clinical report

Ronald G. Verrett, DDS, MS,a and David A. Kaiser, DDS, MSDb

Department of Prosthodontics, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio

Dental School, San Antonio, Texas

Commonly observed complications associated with a conventional fixed partial denture (FPD) include

loss of retention and tooth fracture. This report describes the occurrence of an unusual FPD abutment

fracture and subsequent treatment. The distal abutment of an FPD developed severe periodontal disease

with mobility. The anterior abutment fractured in the middle of the clinical crown and experienced

cement failure. (J Prosthet Dent 2005;93:21-3.)

ixed partial dentures (FPDs) have been shown to

exhibit clinical complications due to a wide variety of

factors. In a review of the literature, Goodacre et al1

identified the most common FPD complications as caries, need for endodontic treatment, loss of retention, esthetics, periodontal disease, tooth fracture, and

prosthesis fracture. In that review, fracture of an abutment tooth occurred in 3% of prostheses.

The technical and biomechanical complications for

FPDs may result in loss of retention, abutment tooth

fracture, and prosthesis fracture. Technical failures occur

more frequently in FPDs with at least 1 cantilever extension pontic, with the rate of failure increasing as the

length of the cantilever span increases.2,3 Fracture of

an FPD abutment adjacent to a cantilever has been reported to occur twice as frequently as fracture of an

abutment not adjacent to a cantilever.4 Abutment fractures in conventional FPDs have also been documented

in longitudinal clinical studies5; however, abutment

fracture of the type reported here is infrequent.6,7 This

clinical report describes an unusual fracture of an FPD

abutment that occurred within the retainer of a conventional FPD and the subsequent treatment.

CLINICAL REPORT

A 69-year-old woman reported to the University of

Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio Dental

School clinic with a chief complaint that the bridge

on the upper right side was loose. The patient reported

that the FPD had been inserted 12 years ago (Fig. 1).

The FPD was found to be loose at the anterior abutment

(maxillary right second premolar) but remained cemented on the distal abutment (maxillary right second

molar). Clinical and radiographic examination revealed

that the distal abutment had periodontal probing depths

of 8 to 9 mm and exhibited Class III mobility (Fig. 2).

The FPD was successfully removed and the maxillary

right second premolar abutment was found to be fractured in the middle of the clinical crown, between the

a

Assistant Professor.

Professor.

JANUARY 2005

Fig. 1. Maxillary right posterior FPD at time of insertion (12

years previous).

occlusal surface and the finish line of the preparation

(Fig. 3). This abutment had remained asymptomatic despite the fracture of the coronal tooth structure. The

margin remained intact around the circumference of

the preparation. The patient was informed of the clinical

findings and was advised that the maxillary right second

molar was not restorable due to severe periodontal pathology. The maxillary right second premolar had a widened periodontal ligament space (Fig. 3), which is often

indicative of occlusal trauma. This finding was related to

the tipping forces transmitted to this abutment during

occlusal loading of the mobile distal abutment of the

FPD. It was noted that the mandibular right first molar

contacted the distal marginal ridge area of the retainer

on the maxillary right second premolar. The possibility

of supraeruption of an unopposed mandibular second

molar and diminished masticatory ability on the right

side of the arch following extraction of the maxillary second molar was discussed. Treatment options were presented that included replacement of the maxillary right

molars with a removable partial denture (RPD) or with

implant-supported crowns that would likely require adjunctive osseous augmentation. The patient declined the

implant option owing to financial considerations as well

as the RPD option because she did not want to wear a removable prosthesis. The patient stated that her desire

THE JOURNAL OF PROSTHETIC DENTISTRY 21

THE JOURNAL OF PROSTHETIC DENTISTRY

Fig. 2. FPD at time of patient presentation with distal

abutment exhibiting 8 to 9 mm periodontal probing depths

and Class III mobility.

VERRETT AND KAISER

Fig. 3. Removal of FPD revealed horizontal fracture through

anterior abutment.

Fig. 4. Maxillary right second premolar received endodontic

treatment and prefabricated dowel with core foundation. FPD

was sectioned and premolar crown was recemented.

was to retain the maxillary second premolar and to have

the second molar extracted.

Endodontic treatment of the maxillary right second

premolar was accomplished to place a dowel-retained

foundation restoration. The most common dowel and

core complication has been reported to be loosening of

the dowel and root fractures.8 Root fractures have been

reported to account for 3% to 10% of dowel and core

complications, and cemented dowels have been found

to cause the least intraradicular stress.8 A prefabricated

passive parallel dowel (ParaPost Plus; Coltene/

Whaledent, Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio) was adapted to the canal space and cemented with glass ionomer cement

(Ketac-Cem; 3M ESPE, St. Paul, Minn). A prefabricated

post was selected because it was less expensive and did not

require the additional appointment needed to restore the

second premolar with a custom-cast dowel. According to

Summitt et al,9 prefabricated dowels have been shown to

exhibit greater fracture resistance than custom-cast dowels in laboratory studies and to provide a more favorable

prognosis in retrospective clinical studies.

22

Fig. 5. Increased mobility of distal abutment (A), combined

with occlusal forces (B), created shear forces between

abutment anterior abutment and axial walls of retainer. These

forces may result in fracture of abutment (C).

The FPD was then sectioned at the interproximal embrasure between the maxillary second premolar and the

first molar, and the resultant second premolar crown was

repolished. The crown was placed on the tooth and marginal integrity was clinically confirmed. A core foundation of the coronal portion of the maxillary right

second premolar was accomplished using an autopolymerizing hybrid, filled resin composite, reinforced

with titanium (Ti-Core; Essential Dental Systems,

Hackensack, NJ). The resin composite was placed on

the tooth and the crown was fully seated, shaping the

core foundation and simultaneously cementing the

crown (Fig. 4). The nonrestorable maxillary second molar was extracted.

VOLUME 93 NUMBER 1

VERRETT AND KAISER

DISCUSSION

This clinical report describes the catastrophic failure

of an FPD. The etiology was severe periodontal disease

localized to the maxillary second molar that permitted

excessive forces on the second premolar abutment. A

biomechanical challenge was created when the excessively mobile distal abutment was rigidly connected to

an abutment with only limited physiologic mobility.

When an excessively mobile FPD abutment is subjected

to an occlusal force, a torquing force is created on the

other abutment that may result in cement failure or fracture of the abutment (Fig. 5). The forces transmitted to

the anterior abutment in this instance are similar to the

forces that occur on a cantilever FPD abutment adjacent

to the cantilever section when the cantilever is subjected

to occlusal loading.

SUMMARY

An FPD abutment may fracture or the cement within

a retainer can fail when subjected to excessive forces.

Fortunately, retrospective clinical studies of conventional FPD complications have concluded that abutment fracture of the type reported is infrequent.

REFERENCES

1. Goodacre CJ, Bernal G, Rungcharassaeng K, Kan JY. Clinical complications

in fixed prosthodontics. J Prosthet Dent 2003;90:31-41.

JANUARY 2005

THE JOURNAL OF PROSTHETIC DENTISTRY

2. Karlsson S. Failures and length of service in fixed prosthodontics after

long-term function. A longitudinal clinical study. Swed Dent J 1989;13:

185-92.

3. Randow K, Glantz PO, Zoger B. Technical failures and some related

clinical complications in extensive fixed prosthodontics. An epidemiological study of long-term clinical quality. Acta Odontol Scand 1986;44:

241-55.

4. Hammerle CH, Ungerer MC, Fantoni PC, Bragger U, Burgin W, Lang NP.

Long-term analysis of biologic and technical aspects of fixed partial dentures with cantilevers. Int J Prosthodont 2000;13:409-15.

5. Valderhaug J. A 15-year clinical evaluation of fixed prosthodontics. Acta

Odontol Scand 1991;49:35-40.

6. Laurell L, Lundgren D, Falk H, Hugoson A. Long-term prognosis of extensive polyunit cantilevered fixed partial dentures. J Prosthet Dent 1991;66:

545-52.

7. Cheung GSP, Dimmer A, Mellor R, Gale M. A clinical evaluation of conventional bridgework. J Oral Rehab 1990;17:131-6.

8. Goodacre CJ, Spolnik KJ. The prosthodontic management of endodontically treated teeth: a literature review. Part 1. Success and failure data,

treatment concepts. J Prosthodont 1994;3:243-50.

9. Summitt JB, Robbins JW, Schwartz RS. Fundamentals of operative dentistry.

2nd ed. Carol Stream (IL): Quintessence; 2001. p. 551.

Reprint requests to:

DR RONALD G. VERRETT

DEPARTMENT OF PROSTHODONTICS

UTHSCSA DENTAL SCHOOL

7703 FLOYD CURL DRIVE, MSC 7912

SAN ANTONIO, TX 78229-3900

FAX: 210-567-6376

E-MAIL: verrett@uthscsa.edu

0022-3913/$30.00

Copyright 2005 by The Editorial Council of The Journal of Prosthetic

Dentistry.

doi:10.1016/j.prosdent.2004.10.009

23

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Full Mouth Rehabilitation of The Patient With Severly Worn Out Dentition A Case Report.Documento5 pagineFull Mouth Rehabilitation of The Patient With Severly Worn Out Dentition A Case Report.sivak_198100% (1)

- Design A Fixed Partial DentureDocumento5 pagineDesign A Fixed Partial DentureDeasireeNessuna valutazione finora

- Oh 2010Documento5 pagineOh 2010gbaez.88Nessuna valutazione finora

- Complications and Failures in FPDDocumento94 pagineComplications and Failures in FPDAmar Bhochhibhoya100% (2)

- Fractures Related To Occlusal Overload With Single Posterior Implants A Clinical ReportDocumento6 pagineFractures Related To Occlusal Overload With Single Posterior Implants A Clinical ReportSurya TejaNessuna valutazione finora

- Non Familiar Characterization Using A Loop Connection in A Fixed Partial DentureDocumento3 pagineNon Familiar Characterization Using A Loop Connection in A Fixed Partial DentureAzzam SaqrNessuna valutazione finora

- Article WMC004708 PDFDocumento5 pagineArticle WMC004708 PDFAnonymous 2r6nHhNessuna valutazione finora

- Tooth-Supported Telescopic Prostheses in Compromised Dentitions - A Clinical ReportDocumento4 pagineTooth-Supported Telescopic Prostheses in Compromised Dentitions - A Clinical Reportpothikit100% (1)

- WeeNeutralZoneDocumento7 pagineWeeNeutralZoneGeby JeonNessuna valutazione finora

- Jameson THE USE OF LINER OCCLUSIO PDFDocumento5 pagineJameson THE USE OF LINER OCCLUSIO PDFLucia Lucero Paz OliveraNessuna valutazione finora

- Guided Eruption of Palatally Impacted Canines Through Combined Use of 3-Dimensional Computerized Tomography Scans and The Easy Cuspid DeviceDocumento14 pagineGuided Eruption of Palatally Impacted Canines Through Combined Use of 3-Dimensional Computerized Tomography Scans and The Easy Cuspid DeviceSaurav Kumar DasNessuna valutazione finora

- Endodontc Surgical Management of Mucosal FenistrationDocumento3 pagineEndodontc Surgical Management of Mucosal Fenistrationfun timesNessuna valutazione finora

- Rehabilitation of Sieberts Class III Defect Using Fixed Removable Prosthesis (Andrew's Bridge)Documento5 pagineRehabilitation of Sieberts Class III Defect Using Fixed Removable Prosthesis (Andrew's Bridge)drgunNessuna valutazione finora

- Ammar 2011Documento13 pagineAmmar 2011manju deviNessuna valutazione finora

- Jced 13 E75Documento6 pagineJced 13 E75Ezza RezzaNessuna valutazione finora

- Vertical-Dimension Control During En-MasseDocumento13 pagineVertical-Dimension Control During En-MasseLisbethNessuna valutazione finora

- Restoration of The Severely Decayed Tooth Using Crown Lengthening With Simultaneous Tooth-PreparationDocumento5 pagineRestoration of The Severely Decayed Tooth Using Crown Lengthening With Simultaneous Tooth-PreparationIntelligentiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Isrn Dentistry2012-259891 PDFDocumento7 pagineIsrn Dentistry2012-259891 PDFAdriana Paola Vega YanesNessuna valutazione finora

- Non-Rigid Connector Manages Pier AbutmentDocumento3 pagineNon-Rigid Connector Manages Pier AbutmentIana RusuNessuna valutazione finora

- Prosthetic Rehabilitation of Mandibular Defects With Fixed-Removable Partial Denture Prosthesis Using Precision Attachment - A Twin Case ReportDocumento17 pagineProsthetic Rehabilitation of Mandibular Defects With Fixed-Removable Partial Denture Prosthesis Using Precision Attachment - A Twin Case ReportIvy MedNessuna valutazione finora

- Multidisciplinary Treatment of A Subgingivally Fractured Tooth With Indirect Restoration A Case ReportDocumento5 pagineMultidisciplinary Treatment of A Subgingivally Fractured Tooth With Indirect Restoration A Case ReportEriana 梁虹绢 SutonoNessuna valutazione finora

- Third Molar Autotransplant Planning With A Tooth Replica. A Year of Follow-Up Case ReportDocumento6 pagineThird Molar Autotransplant Planning With A Tooth Replica. A Year of Follow-Up Case ReportAlNessuna valutazione finora

- Dens Evaginatus and Type V Canal Configuration: A Case ReportDocumento4 pagineDens Evaginatus and Type V Canal Configuration: A Case ReportAmee PatelNessuna valutazione finora

- Rescue Therapy With Orthodontic Traction To Manage Severely Impacted Mandibular Second Molars and To Restore An Alveolar Bone DefectDocumento12 pagineRescue Therapy With Orthodontic Traction To Manage Severely Impacted Mandibular Second Molars and To Restore An Alveolar Bone DefectNathália LopesNessuna valutazione finora

- Prosthodontic and Surgical Management of A Completely PDFDocumento5 pagineProsthodontic and Surgical Management of A Completely PDFmoondreamerm2Nessuna valutazione finora

- Taub - Nonunion of Mandibular MidlineDocumento4 pagineTaub - Nonunion of Mandibular MidlineChristopher McMullinNessuna valutazione finora

- Chandhoke2014 PDFDocumento6 pagineChandhoke2014 PDFdrzana78Nessuna valutazione finora

- Peri-Implant Bone Loss As A Function of Tooth-Implant DistanceDocumento7 paginePeri-Implant Bone Loss As A Function of Tooth-Implant DistancekochikaghochiNessuna valutazione finora

- Clinical Outcomes of Metal-Ceramic Vs Metal-Acrylic Resin Implant-Supported Fixed Complete Dental ProsthesesDocumento70 pagineClinical Outcomes of Metal-Ceramic Vs Metal-Acrylic Resin Implant-Supported Fixed Complete Dental ProsthesesPao JanacetNessuna valutazione finora

- Root Resorption A 6-Year Follow-Up Case ReportDocumento3 pagineRoot Resorption A 6-Year Follow-Up Case Reportpaola lopezNessuna valutazione finora

- Mandibular Implant Supported Overdenture As Occlusal Guide, Case ReportDocumento5 pagineMandibular Implant Supported Overdenture As Occlusal Guide, Case ReportFrancisca Dinamarca LamaNessuna valutazione finora

- MainDocumento2 pagineMainسمسمNessuna valutazione finora

- Use of Implants in The Pterygoid Region For Prosthodontic TreatmentDocumento4 pagineUse of Implants in The Pterygoid Region For Prosthodontic TreatmentSidhartha KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Use of Implants in The Pterygoid RegionDocumento4 pagineUse of Implants in The Pterygoid RegionManjulika TysgiNessuna valutazione finora

- An Alternative Solution For A Complex Prosthodontic Problem: A Modified Andrews Fixed Dental ProsthesisDocumento5 pagineAn Alternative Solution For A Complex Prosthodontic Problem: A Modified Andrews Fixed Dental ProsthesisDragos CiongaruNessuna valutazione finora

- Avulsion and Replacement of The Tooth Element Fractured at The Level of The Middle A Case ReportDocumento5 pagineAvulsion and Replacement of The Tooth Element Fractured at The Level of The Middle A Case ReportDr.O.R.GANESAMURTHINessuna valutazione finora

- Intrusion of Incisors in Adult Patients With Marginal Bone LossDocumento10 pagineIntrusion of Incisors in Adult Patients With Marginal Bone LossYerly Ramirez MuñozNessuna valutazione finora

- 2005 Rojas VizcayaDocumento14 pagine2005 Rojas Vizcayacasto.carpetasmiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Tooth TtriyionDocumento5 pagineTooth TtriyionDhanasriNessuna valutazione finora

- Implicaciones Periodontales Del Tratamiento Quirúrgico-OrtodónticoDocumento9 pagineImplicaciones Periodontales Del Tratamiento Quirúrgico-OrtodónticoAlfredo NovoaNessuna valutazione finora

- 2016 Salvation of Severely Fractured Anterior Tooth An Orthodontic ApproachDocumento4 pagine2016 Salvation of Severely Fractured Anterior Tooth An Orthodontic ApproachRajesh GyawaliNessuna valutazione finora

- Chiu 2015 BimaxillaryDocumento36 pagineChiu 2015 BimaxillaryMax FerNessuna valutazione finora

- Gigi Tiruan Lepasan Pada Kasus Sindrom KombinasiDocumento4 pagineGigi Tiruan Lepasan Pada Kasus Sindrom KombinasiAulia HardiantiNessuna valutazione finora

- Digital Imaging in Trauma Part 2Documento9 pagineDigital Imaging in Trauma Part 2Gaurav BasuNessuna valutazione finora

- Ortho Bone ScrewDocumento17 pagineOrtho Bone ScrewmedicalcenterNessuna valutazione finora

- FPD BiomechanicsDocumento8 pagineFPD BiomechanicsVicente CaceresNessuna valutazione finora

- Immediate Implants Placed Into Infected SocketsDocumento5 pagineImmediate Implants Placed Into Infected SocketsLidise Hernandez AlonsoNessuna valutazione finora

- Gate No 2005Documento7 pagineGate No 2005Abhishek ChauhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Horizontal Posts PDFDocumento6 pagineHorizontal Posts PDFaishwarya singhNessuna valutazione finora

- Mermigos 11 01Documento4 pagineMermigos 11 01Sankurnia HariwijayadiNessuna valutazione finora

- ArticleDocumento4 pagineArticleDrRahul Puri GoswamiNessuna valutazione finora

- Berlin Et Al (2023) Multidisciplinary Approach For Autotransplantation and Restoration of A Maxillary PremolarDocumento7 pagineBerlin Et Al (2023) Multidisciplinary Approach For Autotransplantation and Restoration of A Maxillary PremolarISAI FLORES PÉREZNessuna valutazione finora

- Miyahira2008 - Miniplates As Skeletal Anchorage For Treating Mandibular Second Molar ImpactionsDocumento4 pagineMiyahira2008 - Miniplates As Skeletal Anchorage For Treating Mandibular Second Molar ImpactionsNathália LopesNessuna valutazione finora

- Pi Is 0889540615013311Documento5 paginePi Is 0889540615013311msoaresmirandaNessuna valutazione finora

- 2004-AJODO-Joondeph-Mandibular Midline Osteotomy For ConstrictionDocumento3 pagine2004-AJODO-Joondeph-Mandibular Midline Osteotomy For ConstrictionAlejandro RuizNessuna valutazione finora

- Ridge Preservation Techniques For Implant Therapy: JO M I 2009 24 :260-271Documento12 pagineRidge Preservation Techniques For Implant Therapy: JO M I 2009 24 :260-271Viorel FaneaNessuna valutazione finora

- Overdenture Abutments Under A Fixed Partial Denture: Case Report of A Preventive Prosthodontic ApproachDocumento4 pagineOverdenture Abutments Under A Fixed Partial Denture: Case Report of A Preventive Prosthodontic ApproachDame rohanaNessuna valutazione finora

- Peri-Implantitis Artikel 7-10Documento33 paginePeri-Implantitis Artikel 7-10Radman HaghighatNessuna valutazione finora

- Short ImplantsDa EverandShort ImplantsBoyd J. TomasettiNessuna valutazione finora

- Avoiding and Treating Dental Complications: Best Practices in DentistryDa EverandAvoiding and Treating Dental Complications: Best Practices in DentistryDeborah A. TermeieNessuna valutazione finora

- Commentary: Provisional Restorations For Anterior ImplantsDocumento1 paginaCommentary: Provisional Restorations For Anterior ImplantsCarlos NaupariNessuna valutazione finora

- Adisa. Clinico-Pathological Profile of Head and Neck MalignanciesDocumento31 pagineAdisa. Clinico-Pathological Profile of Head and Neck MalignanciesCarlos NaupariNessuna valutazione finora

- Difficulty IndexDocumento7 pagineDifficulty IndexRobins DhakalNessuna valutazione finora

- Mertens, 8 Años HibridaDocumento10 pagineMertens, 8 Años HibridaCarlos NaupariNessuna valutazione finora

- J 1600-0757 2007 00243 XDocumento20 pagineJ 1600-0757 2007 00243 XCarlos NaupariNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 s2.0 S0002817714601173 MainDocumento4 pagine1 s2.0 S0002817714601173 MainCarlos NaupariNessuna valutazione finora

- Fisher 10 Años RCT HibridaDocumento11 pagineFisher 10 Años RCT HibridaCarlos NaupariNessuna valutazione finora

- 2014 Wittneben Rs Cementadas Vs Atornilladas ResaltadoDocumento16 pagine2014 Wittneben Rs Cementadas Vs Atornilladas ResaltadoCarlos NaupariNessuna valutazione finora

- Articulo ImplantesDocumento9 pagineArticulo ImplantesCarlos NaupariNessuna valutazione finora

- Dental Wear6Documento9 pagineDental Wear6Carlos NaupariNessuna valutazione finora

- Monolithic CAD CAM Lithium Disilicate Versus VeneeredDocumento10 pagineMonolithic CAD CAM Lithium Disilicate Versus VeneeredCarlos NaupariNessuna valutazione finora

- TMD AnxiousDocumento9 pagineTMD AnxiousCarlos NaupariNessuna valutazione finora

- List Meta AnalisisDocumento22 pagineList Meta AnalisisCarlos NaupariNessuna valutazione finora

- The Microflora Adjacent To Ossointegrated Implants Supporting Maxillary Removable ProstheresDocumento7 pagineThe Microflora Adjacent To Ossointegrated Implants Supporting Maxillary Removable ProstheresCarlos NaupariNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 s2.0 S002239131360030X MainDocumento6 pagine1 s2.0 S002239131360030X MainAmar Bhochhibhoya100% (1)

- Protocolo Implantes Carga 3Documento15 pagineProtocolo Implantes Carga 3Carlos NaupariNessuna valutazione finora

- 1 s2.0 S0022391313600281 MainDocumento8 pagine1 s2.0 S0022391313600281 MainKiky COutezNessuna valutazione finora

- Multilink-Variolink N PRO 634456 REV1 eDocumento6 pagineMultilink-Variolink N PRO 634456 REV1 eMihaela SpiridonNessuna valutazione finora

- 01 - 004 An Indirect Cast Post and Core TechniqueDocumento3 pagine01 - 004 An Indirect Cast Post and Core TechniqueRimy Singh100% (1)

- Odontogenic CystDocumento16 pagineOdontogenic CystMahsaNessuna valutazione finora

- Tehnica Bulk FillDocumento6 pagineTehnica Bulk FillVictor MarcautanNessuna valutazione finora

- 6 Philosophies in Full Mouth Rehabilitation A Systematic Review PDFDocumento10 pagine6 Philosophies in Full Mouth Rehabilitation A Systematic Review PDFPremshith CpNessuna valutazione finora

- Steiner Analysis Cecil CDocumento6 pagineSteiner Analysis Cecil Cjeff diazNessuna valutazione finora

- Infection of The JawDocumento51 pagineInfection of The JawMutia Safitri0% (1)

- Evolution of OcclusionDocumento11 pagineEvolution of OcclusiondeekshampdcNessuna valutazione finora

- Diagnosis in Orthodontics - Part IIIDocumento38 pagineDiagnosis in Orthodontics - Part IIIkaran patelNessuna valutazione finora

- DentistryDocumento22 pagineDentistryDrShweta SainiNessuna valutazione finora

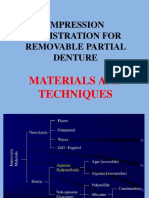

- Impression Registration Rpd-TechniqueDocumento19 pagineImpression Registration Rpd-TechniqueTaha AlaamryNessuna valutazione finora

- Diseases of the Pulp: Causes, Types and TreatmentDocumento15 pagineDiseases of the Pulp: Causes, Types and TreatmentNikita KamatNessuna valutazione finora

- Prevention of Dental CariesDocumento6 paginePrevention of Dental CariesRadhwan Hameed AsadNessuna valutazione finora

- Procedure ListDocumento20 pagineProcedure ListsoyrolandoNessuna valutazione finora

- Ceramics 2005Documento26 pagineCeramics 2005Olariu FaneNessuna valutazione finora

- Seminar ON: Department of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, Dayananda Sagar College of Dental SciencesDocumento25 pagineSeminar ON: Department of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, Dayananda Sagar College of Dental SciencesRiddhi Rathi Shet100% (3)

- Sample Prometric Dental MCQ BookletDocumento12 pagineSample Prometric Dental MCQ BookletMrunal Doiphode80% (15)

- MLV136 REV C Locator PresentationDocumento58 pagineMLV136 REV C Locator PresentationS. BenzaquenNessuna valutazione finora

- Mismanagement of Dentoalveolar PainDocumento7 pagineMismanagement of Dentoalveolar PainEmily AgueroNessuna valutazione finora

- Bleaching: What Causes Staining? Special Considerations For Bleaching TraysDocumento2 pagineBleaching: What Causes Staining? Special Considerations For Bleaching TraysRachel OakesNessuna valutazione finora

- Reling Rebasing 1Documento45 pagineReling Rebasing 1lisa chanNessuna valutazione finora

- OVERLAYDocumento24 pagineOVERLAYJose Luis Celis100% (3)

- Dowel Pin - Snap Fit Technique: A Novel Split Cast TechniqueDocumento4 pagineDowel Pin - Snap Fit Technique: A Novel Split Cast TechniqueIJAR JOURNALNessuna valutazione finora

- Vital Pulp Therapy for Immature TeethDocumento54 pagineVital Pulp Therapy for Immature TeethbrahmannaNessuna valutazione finora

- Periodontal Regeneration: Leonardo Mancini, Adriano Fratini and Enrico MarchettiDocumento12 paginePeriodontal Regeneration: Leonardo Mancini, Adriano Fratini and Enrico MarchettiYou're Just As Sane As DivaNessuna valutazione finora

- TOMAC: An Orthognathic Treatment Planning System Part 1 Soft-Tissue AnalysisDocumento89 pagineTOMAC: An Orthognathic Treatment Planning System Part 1 Soft-Tissue AnalysisDrKamran Momin100% (1)

- Orthodontics Principles and PracticeDocumento1 paginaOrthodontics Principles and PracticeAimee WooNessuna valutazione finora

- Monoplane Occlusion Summary ReviewDocumento2 pagineMonoplane Occlusion Summary Reviewangepange5Nessuna valutazione finora

- Endo-Perio Lesions Diagnosis and Clinical ConsiderationsDocumento8 pagineEndo-Perio Lesions Diagnosis and Clinical ConsiderationsBejan OvidiuNessuna valutazione finora

- Pini Prato and Chambrone 2019-Journal - of - PeriodontologyDocumento5 paginePini Prato and Chambrone 2019-Journal - of - PeriodontologyJayra Elieth Mendoza GomezNessuna valutazione finora