Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

A Survey of The Educational Environment For Oncologists As Perceived by Surgical Oncology Professionals in India

Caricato da

Karl AbiaadTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

A Survey of The Educational Environment For Oncologists As Perceived by Surgical Oncology Professionals in India

Caricato da

Karl AbiaadCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Are et al.

World Journal of Surgical Oncology 2012, 10:18

http://www.wjso.com/content/10/1/18

RESEARCH

WORLD JOURNAL OF

SURGICAL ONCOLOGY

Open Access

A survey of the educational environment for

oncologists as perceived by surgical oncology

professionals in India

Chandrakanth Are1*, Madhuri Are2, Hemanth Raj3, Vijayakumar Manavalan4, Lois Colburn5 and Hugh Stoddard6

Abstract

Background: The current educational environment may need enhancement to tackle the rising cancer burden in

India. The aim of this study was to conduct a survey of Surgical Oncologists to identify their perceptions of the

current state of Oncology education in India.

Methods: An Institutional Review Board approved questionnaire was developed to target the audience of the

2009 annual meeting of the Indian Association of Surgical Oncology in India. The survey collected demographic

information and asked respondents to provide their opinions about Oncology education in India.

Results: A total of 205 out of 408 attendees participated in the survey with a 42.7% response rate. The majority of

respondents felt that Oncology education was poor to fair during medical school (75%), residency (56%) and for

practicing physicians (71%). The majority of participants also felt that the quality of continuing medical education

was poor and that minimal emphasis was placed on evidence based medicine.

Conclusions: The results of our survey demonstrate that the majority of respondents feel that the current

educational environment for Oncology in India should be enhanced. The study identified perceptions of several

gaps and needs, which can be the targets for implementing measures to enhance the training of Oncology

professionals.

Keywords: Education, Oncology, perceptions, survey, India

Background

According to the World Cancer Report released by the

International Agency for Research in Cancer (IARC) in

2008, cancer has surpassed cardiovascular disease as the

leading cause of death in January 2010 [1]. The report estimated that in 2008 there will be 12 million new cases,

7 million deaths and 25 million persons living with cancer

within five years of diagnosis [1]. By 2030, it is estimated

that there will be 26 million new cases diagnosed annually.

This increase in the global cancer burden will be mainly

due to a disproportionate rise of newly diagnosed cancer

cases in the developing countries such as India. India,

China and Russia are predicted to account for more than

half (53%) of the cancer cases and 60% of the cancerrelated deaths [1]. Several factors have been cited for this

* Correspondence: care@unmc.edu

1

Department of Surgery, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

disproportionate rise of new cancer cases in the developing world such as, rising population [2], enhanced life

span [3-5], greater tobacco consumption [6-8] and rising

body mass index [9-16].

The challenge of tackling this rising cancer burden in

the developing world requires an adequate number of

health care professionals who are trained in Oncology. It

is well known that there are fewer health care professionals who live in the developing world countries [17].

The World Health Organization (WHO) report in 2006

noted that, in absolute terms, countries like India, Bangladesh and Indonesia have the greatest shortage of

health service providers [17]. It is estimated that an

increase of 50% in the number of providers is needed to

address the shortages in countries like India [17]. Unfortunately, the data also suggest that the existing educational system for training Oncology care providers,

although currently adequate, is not capable of supporting

2012 Are et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in

any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Are et al. World Journal of Surgical Oncology 2012, 10:18

http://www.wjso.com/content/10/1/18

increases of this magnitude [3]. As of 2009 there were six

Surgical Oncology fellowship (Mch) programs in India

that could train a total of approximately 16 candidates

per year [3]. There are plans to increase this number and

some increases in the number of Mch (50) and DNB (20)

training positions have been noted since 2009. India was

also one of the earliest countries in the world to offer

specialty training in Surgical Oncology with an awarded

degree. Despite this increase in the number of training

positions in Surgical Oncology, the rising cancer burden

suggests that an enhancement in the training and educational environment for Surgical Oncology professionals is

needed in India.

To undertake such an enhancement would require the

collaboration of Surgical Oncologists currently practicing

in India. The study reported here was a survey of practicing Surgical Oncology professionals that was designed to:

a) assess the current educational environment for Oncology in India and b) identify the perceived gaps and needs

in Oncology education that need to be addressed.

Methods

A survey instrument was designed and delivered to Surgical Oncologists who attended the annual meeting of the

Indian Association of Surgical Oncology (IASO) in 2009.

A review of relevant literature did not reveal any specific

reports or appropriate survey instruments that would

assess the educational environment for Oncologists in

India. A 31 item questionnaire was developed by the

authors. The questionnaire and protocol were approved

by the University of Nebraska Medical Center Institutional Review Board as exempt research (IRB: 385-09EX). The questionnaire was originally developed as a

web-based form in Survey Monkey that could be

accessed during the IASO 2009. Due to difficulties of

internet access at the meeting venue, a printed version of

the survey was also made available.

Participants were recruited via signage and announcements during the conference. The survey administration

took place in a dedicated space in the conference facility

and the authors were available to answer any questions

from prospective participants about either the survey

form itself or about accessing Survey Monkey. Completion time ranged from 15 to 30 minutes, depending on

which format of the survey was used and the time spent

completing open-ended responses. Each participant

received a 1 giga byte USB stick as a gift after completing the survey. Data were analyzed using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) v17. Descriptive

analyses were done on the demographic and personal

data provided by respondents and the responses to the

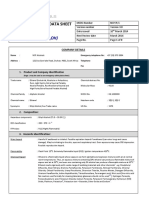

survey items. A sample of the survey instrument is

shown in Figure 1

Page 2 of 6

Results and discussion

There were a total of 220 surveys that were collected

from 480 attendees at the IASO meeting (120 via Survey

Monkey and 88 via print format). After reviewing the

data obtained via Survey Monkey, 15 surveys were discarded due to substantial missing data resulting from

internet access issues. The response rate based on the

remaining 205 surveys was response rate of 42.7%.

Table 1 provides details on the demographic characteristics of those completing the survey. Over half of the

respondents were younger than 40 and were within ten

years of completing their initial surgical training and

92% were male. Sixty four percent of respondents indicated having completed fellowship training in Surgical

Oncology. The vast majority of participants (86%)

reported that they were currently practicing in an academic setting. Nearly 60% worked in a government run

medical school or hospital.

Oncology education resources

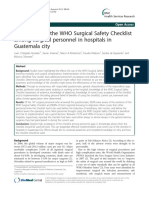

The majority of respondents indicated that standards/

facilities or resources for Oncology education in India

were fair to poor at the undergraduate and residency

education level as well as for physicians currently in

practice. (Table 2 and Figure 2) Despite the aforementioned paucity of fellowship training opportunities in

India, 68% of those responding indicated that the standards/facilities or resources were good or excellent at

the fellowship level. The least conducive environments

for cancer education were considered to be for medical

students, with 75% responding fair or poor and for practicing physicians with 71% reporting fair or poor.

Those who responded either fair or poor to any of

these items were also asked to write details about their

response. Common themes identified among the text

responses were: lack of awareness by physicians and the

public about the problem, lack of a structured Continuing Medical Education (CME) system for practicing physicians, the presence of an old-style curriculum in

medical school, lack of regional cancer facilities, too few

training programs beyond initial residency, and lack of

short-term fellowship programs.

Participation in Continuing Medical Education (CME)

Nearly all (99%) who responded indicated that they completed some type of CME activity within the year prior to

the survey. The preferred formats for CME were live

courses (89%), hospital grand rounds (57%), journal CME

(36%), and review courses (28%). Newer formats for CME

such as internet CME and live webinars were mentioned

by 14% or fewer of the respondents.

Over-two thirds of respondents indicated there were

adequate opportunities for CME in India. The nearly

Are et al. World Journal of Surgical Oncology 2012, 10:18

http://www.wjso.com/content/10/1/18

Page 3 of 6

Figure 1 A sample of the survey instrument.

one-third who felt there were inadequate CME opportunities indicated a wide range of issues including: the

need for more local programs, poor communication of

existing CME opportunities, and the poor quality of current CME programs. Comments from those responding

there were few opportunities in Oncology CME indicated that there was a need for more local programs

aimed at general surgeons, CME Oncology content that

is specific to Oncology issues in India, as well as the

awareness that Oncology as a formal specialty is still

relatively new in India.

Application of Evidence-based Medicine (EBM)

Nearly 77% of survey respondents felt that there is littleto-none or some emphasis placed on EBM in cancer

care in India. Respondents attributed this to be due to a

lack of resources, awareness and emphasis on EBM

combined with the absence of uniformity of protocols in

treatment. They also noted that the only protocols available are from outside the country and they do not seem

to be appropriate for the population in India.

Conclusions

To address the Oncology education needs of physicians

in India, any changes or enhancements should start

from feedback from Oncology professionals in the country. The survey of Indian Oncology professionals for the

current study described the viewpoint of those professionals about the state of Oncology education in that

country and generated some suggestions about means to

resolve the perceived deficiencies.

The International Agency for Research in Cancer

report predicted a rise in the cancer burden worldwide

with a disproportionate rise in developing countries such

as India [1]. It is also documented that countries like

India have health care workforce shortages [3,17-19].

One avenue to address the health care workforce shortage is to educate a larger number of professionals and to

expand the continuing educational opportunities for

those already in practice. Most developing world countries do not have the educational capacity to increase the

pool of health care workers rapidly [3]. For example,

although some increases in the number of fellowship

Are et al. World Journal of Surgical Oncology 2012, 10:18

http://www.wjso.com/content/10/1/18

Page 4 of 6

Table 1 Demographics of survey participants

n

% of

respondents

Male

Female

186

17

91.6

8.4

Age

29 or younger

30-39

40-49

50 and older

31

78

47

45

15.4

38.8

23.4

22.4

57

34

33

50

32.8

19.5

19.0

28.7

71

126

36.0

64.0

166

27

86.0

14.0

49

88

30

29.3

52.7

18.0

59

110

15

32.1

59.8

8.2

Gender

Time since completion of residency

5 years or less

6 to 10 years

11 to 15 years

16 years or more

Completed Oncology Fellowship (Mch or

DNB)

Yes

No

Type of Practice

Academic

Non-academic

Time spent teaching

25% of less

26 to 50%

More than 50%

Employment Type

Corporate

Government

Private Practice

Mch: Magister Chirurgiae

DNB: Diplomate of National Board

training position in India has happened in the last few

years, this number may still be inadequate to meet the

rising burden of new cancer cases.

The ability to address the disease burden in any population depends on the availability of an adequate pool of

appropriately trained health care professionals. This in

turn requires the presence of a satisfactory number of

training positions that will prepare those health care

professionals. Beyond the training at the undergraduate,

Table 2 How would you rate the standards/facilities/

resources for cancer education in the following areas in

India?

n

Poor

n(%)

Fair

n(%)

Good

n(%)

Excellent

n(%)

Medical school

193

68 (35)

78 (40)

44 (23)

3 (2)

Post-graduate training

(residency)

190

20 (10)

88 (46)

79 (42)

3 (2)

Mch or DNB

(Fellowship)

186

22 (12)

37 (20)

106 (57)

21 (11)

Practicing physicians

175

63 (36)

62 (35)

47 (27)

3 (2)

Mch: Magister Chirurgiae

DNB: Diplomate of National Board

graduate and fellowship levels, there needs to be a systematic process for providing continuing medical education so that medical care adheres to the most current

evidence based principles. The lack of resources for

training and continuing medical education would

exacerbate a shortage of health care professionals and

can pose a major problem. A well-designed CME program for evidence-based practice in Oncology would

contribute significantly to alleviating such shortages.

The results of our survey demonstrated that even among

a group of highly specialized Oncology professionals, there

was a sense that cancer education is grossly inadequate at

several levels, except for residency and fellowship training.

This was felt most acutely during medical school training

where a large percentage (75%) felt that cancer education

was poor to fair. It appears that the majority of Indian

medical schools do not have separate academic divisions

or student rotations dedicated to Oncology. The current

curricula appear to be outdated without sufficient emphasis on how to manage the rising number of cancer cases.

This is compounded by the fact there is a shortage of adequately trained faculty. Although not as acute, the survey

respondents also noted that Oncology education is not

ideal during post graduate training as well. The only segment of health care workers felt to have an adequate educational environment in Oncology are candidates in

fellowship training. Given this and the small number of

fellowship positions [3] currently available, major reforms

are needed to address the problem in the near future.

The resources available to provide education for practicing physicians are also felt to be inadequate and this has

been noted by other authors [20]. This is of concern since

these individuals are not only the ones responsible for

treating patients but also training the future pool of health

care workers. Although the majority of survey respondents

reported attendance at CME, many also felt there is both a

shortage of CME activities and that the quality of the current activities needs to be improved. The majority of the

respondents indicated they obtain their CME from attending live courses. This can be a problem in a large country

such as India with limited resources and a lack of streamlined transportation facilities. There is a distinct under

usage of web based educational activities which seems ironic given the perception of India as a technology center.

For a country like India with a rapidly developing information technology framework, web based activities can provide a solution to address CME in remote locations.

The lack of educational curricula and CME translates

into inadequate emphasis placed on evidence based practice of cancer care. Nearly four-fifths of the respondents

noted that little-to-none or only some emphasis is placed

on evidence based medicine. This is particularly noteworthy in cancer care where the field is in constant flux

with the availability of new technology, drugs and

Are et al. World Journal of Surgical Oncology 2012, 10:18

http://www.wjso.com/content/10/1/18

Page 5 of 6

Figure 2 How would you rate the standards/facilities/resources for cancer education in the following areas in India.

guidelines on a regular basis. In Oncology, it is vitally

important to make current treatment guidelines available

to health care professionals. Lastly there are no uniform

guidelines developed for the Indian population since those

available from the developed world may not always be

applicable to the developing world.

The results of our survey point out that, Oncology professionals perceive gaps and needs for enhanced cancer

education in India. Although this study employed an

exploratory survey instrument, these findings can still be

of help in initiating efforts to improving Oncology education in India. Such measures may include: increasing training positions in Oncology, promote awareness of

Oncology as a required specialty, updating and streamlining the existing curricula, making CME more widely available and encouraging adherence to evidence based

medicine.

There are several limitations to this study. First, it represents the findings of a limited, non-representative sample.

Although the meeting at which the survey was conducted

was well attended and the survey response rate was adequate, additional investigation is called for before substantial investments are made. Also, although India is

representative of the conditions of most developing countries, the educational context may differ in other countries

even though the problems of provider shortages and

inadequate training are similar in much of the developing

world.

The results of this study demonstrate that there are

several avenues for enhancement in Oncology education

for health care professionals across the spectrum of

training and practice in India. In addition, written comments from the respondents helped us to identify gaps

and needs for CME. A follow-up survey administered to

a representative sample in the future may be useful in

targeting measures to address these gaps and needs and

should help create the pool of health care professionals

needed to tackle the oncoming rising burden of cancer

cases in developing countries.

List of abbreviations

Mch: Magister Chirurgiae; DNB: Diplomate of National Board

Author details

1

Department of Surgery, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE.

2

Cancer Pain and Palliative Care, University of Nebraska Medical Center,

Omaha, NE. 3Cancer Institute (WIA), Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. 4Kidwai

Memorial Institute of Oncology, Benagaluru, Karnataka, India. 5Executive

Director, Center for Continuing Education, University of Nebraska Medical

Center, Omaha, NE. 6Curriculum and Educational Research Office, University

of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE.

Authors contributions

CA: Design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting

of manuscript, critical revision, final approval

MA: Design, drafting of manuscript, critical revision, final approval

HR: Design, acquisition of data, critical revision, final approval

MV: Design, acquisition of data, critical revision, final approval

LC: Design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of

manuscript, critical revision, final approval

HS: Critical revision, final approval

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Received: 25 May 2011 Accepted: 23 January 2012

Published: 23 January 2012

References

1. [http://www.iarc.fr/en/publications/pdfs-online/wcr/2008/index.php],

accessed May 2011.

Are et al. World Journal of Surgical Oncology 2012, 10:18

http://www.wjso.com/content/10/1/18

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

Page 6 of 6

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: World

population prospects: the 2006 revision. New York. United Nations; 2007.

Are C, Colburn L, Rajaram S, Vijayakumar M: Disparities in cancer care

between the United States of America and India and opportunities for

surgeons to lead. J Surg Oncol 2010, 102:100-5.

Yang G, Hu J, Rao KQ, Ma J, Rao C, Lopez AD: Mortality registration and

surveillance in China: History, current situation and challenges. Popul

Health Metr 2005, 16:3.

Yang GH, Huang ZJ, Tan J: Priorities of disease control in China-analysis

on mortality data of National disease Surveillance Points system.

Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 1996, 17:199-202.

IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans.

Betel quid and areca nut chewing and some areca-nut-derived

nitrosamines. Lyon France: International Agency for Research in Cancer;

2004, 85: [http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Monographs/vol85/mono85.pdf],

accessed - January 2012.

[http://www.fao.org/english/newsroom/news/2003/26919-en.html], accessed

May 2011.

Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I: Mortality in relation to smoking:

50 years observations on male British doctors. BMJ 2004, 328:1519.

Samanic C, Chow WH, Gridley G, Jarvholm B, Fraumeni JF Jr: Relation of

body mass index to cancer risk in 362,552 Swedish men. Cancer Causes

Control 2006, 17:901-9.

Lukanova A, Bjor O, Kaaks R, Lenner P, Lindahl B, Hallmans G, Stattin P:

Body mass index and cancer: results from the Northern Sweden Health

and Disease cohort. Int J Cancer 2006, 118:458-66.

Larsson SC, Permert J, Hakansson N, Naslund I, Bergkvist L, Wolk A: Overall

obesity, abdominal adiposity, diabetes and cigarette smoking in relation

to the risk of pancreatic cancer in two Swedish population-based

cohorts. Br J Cancer 2005, 93:1310-5.

Kuriyama S, Tsubono Y, Hozawa A, Shimazu T, Suzuki Y, Koizumi Y, Suzuki Y,

Ohmori K, Nishino Y, Tsuji I: Obesity and risk of cancer in Japan. Int J

Cancer 2005, 113:148-57.

Jee SH, Yun JE, Park EJ, Cho ER, Park IS, Sull JW, Ohrr H, Samet JM: Body

mass index and cancer risk in Korean men and women. Int J Cancer

2008, 15:1892-6.

Mendes MA, Monteiro CA, Popkin MB: Overweight exceed underweight

among women in developing countries. Am J Clin Nutr 2005, 81:714-21.

Subramanian SV, Perkins JM, Ozaltin E, Davey Smith G: Weight of nations: a

socioeconomic analysis of women in low to middle income countries.

Am J Clin Nutr 2011, 93:413-21.

Nube M, Asenso-Okeyere WK, van den Boom GJ: Body mass index as

indicator of standard of living in developing countries. Eur J Clin Nutr

1998, 52:136-44.

, http://www.who.int/whr/2006/06_chap1_en.pdf- accessed May 2011.

, http://www.globalhealth.org/health_systems/health_care_workers/accessed May 2011.

, http://www.whoindia.org/EN/Section20/Section385/Section401_1573.htmaccessed May 2011.

, http://www.who.int/healthinfo/paper51.pdf- accessed May 2011.

doi:10.1186/1477-7819-10-18

Cite this article as: Are et al.: A survey of the educational environment

for oncologists as perceived by surgical oncology professionals in India.

World Journal of Surgical Oncology 2012 10:18.

Submit your next manuscript to BioMed Central

and take full advantage of:

Convenient online submission

Thorough peer review

No space constraints or color figure charges

Immediate publication on acceptance

Inclusion in PubMed, CAS, Scopus and Google Scholar

Research which is freely available for redistribution

Submit your manuscript at

www.biomedcentral.com/submit

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Musculoskeletal Cancer Surgery - Malawer PDFDocumento592 pagineMusculoskeletal Cancer Surgery - Malawer PDFanggita100% (1)

- MSDS Light SpiritDocumento9 pagineMSDS Light Spiritjhonni sigiroNessuna valutazione finora

- The Impact of Patient Safety CultureDocumento9 pagineThe Impact of Patient Safety CultureAnsu MaliyakalNessuna valutazione finora

- Group 6 Capstone III Draft1Documento11 pagineGroup 6 Capstone III Draft1api-522252407Nessuna valutazione finora

- Medical Students' Career Preferences in Bangladesh: Research Open AccessDocumento13 pagineMedical Students' Career Preferences in Bangladesh: Research Open Accessbros27811Nessuna valutazione finora

- s12909 021 02870 XDocumento10 pagines12909 021 02870 XOMAR EL HAMDAOUINessuna valutazione finora

- Capstone Draft IVDocumento13 pagineCapstone Draft IVapi-524151719Nessuna valutazione finora

- 2023 06 19 23291617 FullDocumento28 pagine2023 06 19 23291617 Fullshouka.inNessuna valutazione finora

- CPR JournalDocumento9 pagineCPR JournalDale DeocaresNessuna valutazione finora

- Benefits - and - Challenges - of - Ele 6Documento7 pagineBenefits - and - Challenges - of - Ele 6silfianaNessuna valutazione finora

- Article 3Documento12 pagineArticle 3مالك مناصرةNessuna valutazione finora

- Interventions To Improve Hand Hygiene Compliance in Emergency Departments: A Systematic ReviewDocumento13 pagineInterventions To Improve Hand Hygiene Compliance in Emergency Departments: A Systematic ReviewFaozan FikriNessuna valutazione finora

- Ket ProposalDocumento37 pagineKet ProposalEneyew BirhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Parts of A ReportDocumento12 pagineParts of A ReportVenice De los ReyesNessuna valutazione finora

- The Knowledge, Ability, and Skills of Primary Health Care Providers in SEANERN Countries: A Multi-National Cross-Sectional StudyDocumento8 pagineThe Knowledge, Ability, and Skills of Primary Health Care Providers in SEANERN Countries: A Multi-National Cross-Sectional StudyAzubeda SaidiNessuna valutazione finora

- Could India Become The Digital Pathology Hub of The Future A Consideration of The Prospects of Telepathology OutsourcingDocumento3 pagineCould India Become The Digital Pathology Hub of The Future A Consideration of The Prospects of Telepathology OutsourcingdrsubanNessuna valutazione finora

- Use of Appropriate Healthcare Technologies: A Cross-Sectional Study in Rural Zhejiang of ChinaDocumento9 pagineUse of Appropriate Healthcare Technologies: A Cross-Sectional Study in Rural Zhejiang of ChinaCatarina MaguniNessuna valutazione finora

- Hospital Survey On Patient Safety Culture in Dental Hospitals in The Twin Cities, PakistanDocumento5 pagineHospital Survey On Patient Safety Culture in Dental Hospitals in The Twin Cities, PakistanMuhammad HarisNessuna valutazione finora

- GS62919 JournalDocumento14 pagineGS62919 JournalBEN GURION A/L DAVID / UPMNessuna valutazione finora

- A Melo Blast OmaDocumento10 pagineA Melo Blast Omaputu windaNessuna valutazione finora

- Explorative Study To Assess The Knowledge & Attitude Towards NABH Accreditation Among The Staff Nurses Working in Bombay Hospital, Indore. India.Documento2 pagineExplorative Study To Assess The Knowledge & Attitude Towards NABH Accreditation Among The Staff Nurses Working in Bombay Hospital, Indore. India.International Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)Nessuna valutazione finora

- Healthcare Professionals Knowledge On Cancer Related Fatigue ADocumento9 pagineHealthcare Professionals Knowledge On Cancer Related Fatigue AJuliaNessuna valutazione finora

- Paper Final Complete Group6Documento16 paginePaper Final Complete Group6api-524151719Nessuna valutazione finora

- University of Birmingham: Implementing Clinical Governance in Iranian HospitalsDocumento9 pagineUniversity of Birmingham: Implementing Clinical Governance in Iranian HospitalssunnyNessuna valutazione finora

- Factors Influencing Students To Enroll in Health Information Management ProgramsDocumento18 pagineFactors Influencing Students To Enroll in Health Information Management Programsrobert93Nessuna valutazione finora

- Six Sigma in Healthcare ServiceDocumento7 pagineSix Sigma in Healthcare Service第九組林學謙Nessuna valutazione finora

- Research 09Documento16 pagineResearch 09Nandini SeetharamanNessuna valutazione finora

- 2020 - Quality and Women's Satisfaction With Referral System Systematic ReviewDocumento16 pagine2020 - Quality and Women's Satisfaction With Referral System Systematic ReviewTaklu Marama M. BaatiiNessuna valutazione finora

- GoogleDocumento23 pagineGooglewaseem akhtarNessuna valutazione finora

- Kumpulan Jurnal InternasionalDocumento15 pagineKumpulan Jurnal InternasionalTIKANessuna valutazione finora

- Health Financing For Universal HealthDocumento9 pagineHealth Financing For Universal HealthMirani BarrosNessuna valutazione finora

- BMC Cancer Factors Associated With VIA and CBE in IndonesiaDocumento10 pagineBMC Cancer Factors Associated With VIA and CBE in IndonesiaAmallia PradisthaNessuna valutazione finora

- Bio Medical Waste Management Delhi IndiaDocumento2 pagineBio Medical Waste Management Delhi IndiafriendsofindiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Current and Future Use of Radiological Images in The Management of Gynecological Malignancies - A Survey of Practice in The UKDocumento21 pagineCurrent and Future Use of Radiological Images in The Management of Gynecological Malignancies - A Survey of Practice in The UKKrishna PanduNessuna valutazione finora

- Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices About Biomedical Waste Management Among Healthcare Personnel: A Cross-Sectional StudyDocumento5 pagineKnowledge, Attitude, and Practices About Biomedical Waste Management Among Healthcare Personnel: A Cross-Sectional StudyLa RikiNessuna valutazione finora

- Acceptance of The WHO Surgical Safety Checklist Among Surgical Personnel in Hospitals in Guatemala CityDocumento5 pagineAcceptance of The WHO Surgical Safety Checklist Among Surgical Personnel in Hospitals in Guatemala Citygede ekaNessuna valutazione finora

- Patient Satisfaction With Nursing Care in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocumento12 paginePatient Satisfaction With Nursing Care in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisgiviNessuna valutazione finora

- Health RecordsDocumento36 pagineHealth RecordsMatthew NdetoNessuna valutazione finora

- Online, Face To Face and Hybrid Meetings. What Is The New Normal in The Covid-19 Era? A Global Collaborative Survey by Itrue Group and Urosome Working GroupDocumento14 pagineOnline, Face To Face and Hybrid Meetings. What Is The New Normal in The Covid-19 Era? A Global Collaborative Survey by Itrue Group and Urosome Working Grouptifa huwaidahNessuna valutazione finora

- Research ArticleDocumento14 pagineResearch ArticleShubhaDavalgiNessuna valutazione finora

- Assessment of Evidence-Based Practice EBP Among Physiotherapists in CameroonDocumento10 pagineAssessment of Evidence-Based Practice EBP Among Physiotherapists in CameroonDr. Krishna N. SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- An Insight Into The Undergraduate Medical Research in IndiaDocumento5 pagineAn Insight Into The Undergraduate Medical Research in IndiakarthikscribNessuna valutazione finora

- ContentServer AspDocumento9 pagineContentServer AspDeborah Morales CaychoNessuna valutazione finora

- v2 Covered PDFDocumento52 paginev2 Covered PDFImmanuel Teja HarjayaNessuna valutazione finora

- Melekie-Getahun2015 Article ComplianceWithSurgicalSafetyChDocumento7 pagineMelekie-Getahun2015 Article ComplianceWithSurgicalSafetyChPraveen Pj NaniNessuna valutazione finora

- Assessing Medical Student Documentation Using Simulated Charts in Emergency MedicineDocumento6 pagineAssessing Medical Student Documentation Using Simulated Charts in Emergency MedicineRenzo Iván Marín DávalosNessuna valutazione finora

- Identification of Essential Surgical Competencies To Be Imparted in Urological Residency: A Survey Based StudyDocumento6 pagineIdentification of Essential Surgical Competencies To Be Imparted in Urological Residency: A Survey Based StudyDronacharya RouthNessuna valutazione finora

- Jurnal Ceklis Bs Inggris4Documento12 pagineJurnal Ceklis Bs Inggris4Neni TrianaNessuna valutazione finora

- MohdDocumento6 pagineMohdapouakone apouakoneNessuna valutazione finora

- The Influence of Gender On Clinical Examination Skills of Medical Students in Jordan: A Cross-Sectional StudyDocumento10 pagineThe Influence of Gender On Clinical Examination Skills of Medical Students in Jordan: A Cross-Sectional StudymoNessuna valutazione finora

- Knowledge and Practice Towards Prevention of Surgical Site Infection Among Healthcare Professionals in Buraidah City, Saudi ArabiaDocumento7 pagineKnowledge and Practice Towards Prevention of Surgical Site Infection Among Healthcare Professionals in Buraidah City, Saudi ArabiamajedNessuna valutazione finora

- ProQuestDocuments 2014-03-17Documento11 pagineProQuestDocuments 2014-03-17kikiNessuna valutazione finora

- HGHJGVVVDocumento9 pagineHGHJGVVVMohamed SaudNessuna valutazione finora

- Implementation of A Smartphone Application in Medical Education: A Randomised Trial (iSTART)Documento9 pagineImplementation of A Smartphone Application in Medical Education: A Randomised Trial (iSTART)Abdiaziz WalhadNessuna valutazione finora

- PSSJN - Volume 8 - Issue 3 - Pages 68-83Documento16 paginePSSJN - Volume 8 - Issue 3 - Pages 68-83Smith MpNessuna valutazione finora

- Researcharticle Open Access: Tigist EngdaDocumento12 pagineResearcharticle Open Access: Tigist EngdasitiNessuna valutazione finora

- Assessment On CPR Knowledge AnDocumento7 pagineAssessment On CPR Knowledge AnGolden HopeNessuna valutazione finora

- Determinants of Cancer Screening Awareness and Participation Among Indonesian WomenDocumento11 pagineDeterminants of Cancer Screening Awareness and Participation Among Indonesian WomenVilla Sekar citaNessuna valutazione finora

- 06 AbstractDocumento3 pagine06 AbstractmacmohitNessuna valutazione finora

- Assessing The Awareness and Factors Contributing To Unawareness of The MLT Field Among Different Univ-3Documento14 pagineAssessing The Awareness and Factors Contributing To Unawareness of The MLT Field Among Different Univ-3NoorNessuna valutazione finora

- A Questionnaire Based Study-Assessment of KnowledgDocumento5 pagineA Questionnaire Based Study-Assessment of KnowledgAnitha NoronhaNessuna valutazione finora

- Strategies to Explore Ways to Improve Efficiency While Reducing Health Care CostsDa EverandStrategies to Explore Ways to Improve Efficiency While Reducing Health Care CostsNessuna valutazione finora

- Incorrectly: CorrectlyDocumento25 pagineIncorrectly: CorrectlypikachuNessuna valutazione finora

- The Cost of PainDocumento121 pagineThe Cost of PainDavid IrelandNessuna valutazione finora

- Wegener SDocumento7 pagineWegener SJeffrey Ian M. KoNessuna valutazione finora

- Introduction To Corrective Health MedicineDocumento107 pagineIntroduction To Corrective Health MedicineBradford S. Weeks100% (2)

- Periodontal Pocket PathogenesisDocumento23 paginePeriodontal Pocket Pathogenesisperiodontics07Nessuna valutazione finora

- Prelim OncologyDocumento10 paginePrelim OncologyErl D. MelitanteNessuna valutazione finora

- Acute CholecystitisDocumento28 pagineAcute CholecystitisWilfredo Mata JrNessuna valutazione finora

- Practice Test Questions Downloaded From FILIPINO NURSES CENTRALDocumento5 paginePractice Test Questions Downloaded From FILIPINO NURSES CENTRALFilipino Nurses CentralNessuna valutazione finora

- Integrating Cervical Cancer Prevention Services Into The Care and Treatment of Women Living With HIV/AIDS in Cote D'ivoire PowerpointDocumento13 pagineIntegrating Cervical Cancer Prevention Services Into The Care and Treatment of Women Living With HIV/AIDS in Cote D'ivoire PowerpointJhpiegoNessuna valutazione finora

- Retire HappyDocumento266 pagineRetire HappyEdsel Llave100% (3)

- Rationale AtheroDocumento6 pagineRationale AtheroMary Lorraine LoridoNessuna valutazione finora

- Manual of Diagnostic Antibodies For Immunohistology - 1841101001Documento539 pagineManual of Diagnostic Antibodies For Immunohistology - 1841101001dudapaskasNessuna valutazione finora

- Somatic Cell GeneticsDocumento47 pagineSomatic Cell Geneticsbirhanu mechaNessuna valutazione finora

- Year 9 Biology QuestionsDocumento58 pagineYear 9 Biology QuestionsDuong Kha NhiNessuna valutazione finora

- III D2 - Hypothyroidism-Hyperthyroidism Diagnostic Test, Therapeutic & Educative InterventionsDocumento23 pagineIII D2 - Hypothyroidism-Hyperthyroidism Diagnostic Test, Therapeutic & Educative InterventionsJireh Yang-ed ArtiendaNessuna valutazione finora

- Cytodiagnosis in DermatologyDocumento5 pagineCytodiagnosis in DermatologyDipti MathiasNessuna valutazione finora

- A Subdural HematomaDocumento12 pagineA Subdural HematomaGina Irene IshakNessuna valutazione finora

- 110 TOP SURGERY Multiple Choice Questions and Answers PDF - Medical Multiple Choice Questions PDFDocumento11 pagine110 TOP SURGERY Multiple Choice Questions and Answers PDF - Medical Multiple Choice Questions PDFaziz0% (1)

- 4 1Documento265 pagine4 1sillypoloNessuna valutazione finora

- Celiac Disease: Suggestive Gastrointestinal SymptomsDocumento6 pagineCeliac Disease: Suggestive Gastrointestinal SymptomsJean Pierre Fakhoury100% (1)

- Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals: An Endocrine Society Scientific StatementDocumento50 pagineEndocrine-Disrupting Chemicals: An Endocrine Society Scientific StatementRobin KristófiNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Judge A Dasha in JyotishDocumento2 pagineHow To Judge A Dasha in JyotishRavan SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Mammomat Revelation Product Brochure-2018!01!04848077Documento16 pagineMammomat Revelation Product Brochure-2018!01!04848077Ngọc Hoàng TuấnNessuna valutazione finora

- Pipelle Endometrial Suction Curette Instructions For Use PDFDocumento20 paginePipelle Endometrial Suction Curette Instructions For Use PDFBernadette YapNessuna valutazione finora

- Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Management of Polycystic Ovary SyndromeDocumento14 pagineEpidemiology, Diagnosis, and Management of Polycystic Ovary SyndromeAlyssa JenningsNessuna valutazione finora

- Pharmacogenomics PDFDocumento12 paginePharmacogenomics PDFsivaNessuna valutazione finora

- Main Idea and DetailDocumento19 pagineMain Idea and DetailAbdul Rahman Al Risqi0% (1)

- Lugols SolutionDocumento7 pagineLugols SolutionlaniNessuna valutazione finora