Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Сivil Society in Conflicts: From Escalation to Militarization

Caricato da

Valdai Discussion ClubCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Сivil Society in Conflicts: From Escalation to Militarization

Caricato da

Valdai Discussion ClubCopyright:

Formati disponibili

# 28 VALDAI PAPERS

October 2015

www.valdaiclub.com

CIVIL SOCIETY IN CONFLICTS:

FROM ESCALATION

TO MILITARIZATION

Raffaele Marchetti

About the author:

Raffaele Marchetti

Professor of International Relations, LUISS Guido Carli University of Rome, Italy

Summary

Conflict society 4

The context of civil society activism 4

From conflict escalation to militarization

Mechanisms of politicization 9

Conclusion 12

References 12

CIVIL SOCIETY IN CONFLICTS: FROM ESCALATION TO MILITARIZATION

Civil society actors have become key players in conflicts, especially in intra-state ones.

This has been facilitated by the transformation of conflicts, increasingly characterized by highintensity intra-border ethno-religious tensions and strong international influence by proxy.

The usual take on conflicts focuses on the role of governmental actors, both national and

international. Accordingly, violence and peace are usually considered to be determined above

all by the political decisions of official institutions alone. While this remains partly true, in this

paper I examine the other side of the coin: the non-governmental component in conflicts. Civil

society actors, or as I define them, conflict society organizations, are increasingly central in view

of the high degree of complexity of contemporary conflicts. These are conflicts that can only

be understood by combining macro with micro approaches that focus on society. It is thanks to

the latter approach that it is possible to unpack the political inputs, be they good or bad, which

emerge from below, from the civil society domain, and scale up to the top political echelons.

This is even more so in societies that are highly fragmented and deprived of stable governing

institutions. It is in failing states such as those undergoing ethno-political conflict that much

of politics unfolds on the ground. Hence it is there, at the micro level, that we need to explore

the political dynamics in order to capture fully the profound motives that trigger violence.

It is widely recognized in the literature that civil society plays a key role in fostering

democratic governance in peaceful societies. Yet the political significance of civil society may

be far more prominent in contexts marked by conflict. Being characterized by a higher degree of

politicization and a less structured institutional setting, conflict situations may generate a more

intense mobilization of civil society. While in stable political systems civil society may tend at times

to apathy, in conflict ridden conflict mobilization may suddenly grow. Here politicization is of a

qualitatively different nature, as it occurs in view of the life-or-death nature of politics. Contrary

to peaceful contexts, in conflict situations the existential nature of politics and the securitizations

that follow generate different societal incentives to mobilize (Buzan, Wver, & De Wilde, 1998). The

cross-sectional nature of existential or securitized politics thus yields a quantitatively higher degree

of public action spanning different sectors in society. The different understandings of the causes of

conflict and the adequate responses to them may in turn lead to the formation of civil society actors

and ensuing actions that can either fuel conflict, sustain the status quo, or promote peace.

Current conflicts such as those in Syria, Libya, and Ukraine, or past conflicts as those in

Rwanda, Cyprus, Mozambique, Timor East, former Yugoslavia, or indeed Israel/Palestine may

provide clear examples of the significant role played by societal actors in conflicts.

Valdai Papers #28. October 2015

CIVIL SOCIETY IN CONFLICTS: FROM ESCALATION TO MILITARIZATION

Conflict society

In the studies on civil society and conflicts, considerable attention has been devoted to global

civil society and transnational social movements, and more specifically to their role in preventing

and resolving war (Douma & Klem, 2004; Forster & Mattner, 2006); yet insufficient attention

has been devoted to the role of local civil society in conflict creation as well as in prevention or

resolution. When local civil society is taken into account in the literature on nationalism, civil actors

are often characterized as negative agents in fundamentalist or nationalistic struggles, rather

than as potential agents for peaceful transformation (Kaldor & Muro-Ruiz, 2003). In transition

studies, local civil society is often seen as a player in democratization, diplomacy and economic

modernization that is, in a liberal peacebuilding and peace-consolidating mode (Richmond,

2005). Yet the role of local civil society during conflict periods is often overlooked. In development

studies recently coupled with security studies, civil society in conflict is normally taken to mean

Western-style international NGOs and local Western-funded liberal NGOs (Chandler, 2001), thus

ignoring the wider civil society space beyond NGOs. In what follows, I examine the specificity of

local and international civil society in conflicts.

The term civil society encompasses a wide variety of actors, ranging from local to

international, independent and quasi-governmental players. Conflict tends to shape the identity

and actions of civil society organizations. Because of this I focus on these groups in particular,

defining them as conflict society organizations (CoSOs) (Marchetti & Tocci, 2011a, 2011b).

Conflict society comprises all local civic organizations within conflict contexts and third

countries, as well as international and transnational civic organizations involved in the conflict in

question. By coining the term conflict society rather than simply relying on the looser definition

of civil society in conflict, I wish to convey the understanding that in conflicts, more so than

in other contexts, civil society encompasses both civil and uncivil elements (Chambers &

Kopstein, 2001). However, using the definitions civil and uncivil society would convey the false

understanding that the two types of actors are easily separable: As a matter of fact, in conflict

situations, the two terms become blurred. Conflict society actors are not uniform either; they

include a diversity of different organizations. CoSOs are both local and international groups

that take an active part in a conflict. They include conflict specialists, business, private citizens,

research and education, activists, religion-based groups, foundations and the media.

The context of conflict society activism

The first element that we need to take into account in order to capture the nature and

role of conflict society is the context. Rarely are the implications of context in the development

of civil society openly acknowledged and taken into account by the literature. Yet a study of the

role of civil society in conflict-ridden areas lying beyond Western Europe must account for the

role and implications of context. Hence a first specific variable in our analysis of civil society in

conflict is the context within which it operates. In this respect, several core questions need to

be raised at the outset. Can and does civil society exist in contexts of failed states, authoritarian

Valdai Papers #28. October 2015

CIVIL SOCIETY IN CONFLICTS: FROM ESCALATION TO MILITARIZATION

rule and ethnic nationalism, underdevelopment or over-bearing international presence? The

underlying premise of this paper is that civil society can and does exist in these situations, if

we take a broad enough definition of civil society. Yet its nature as well as its role and functions

are fundamentally shaped by the specific context in question. In so far as civil society is both

an independent agent for change and a dependent product of existing structures, we are likely

to encounter a wide range of civil society actors, including both civil and uncivil, carrying

out a wide range of actions. Examples range from the role of the different religious movements

in Lebanon during and after the war to the current significance of the courts in Somalia

and the different tribal organizations in Libya. More specifically for the purpose of this paper,

several general contextual categories need to be briefly discussed in order to qualify and better

understand the specific contexts in which civil society in conflict operates.

The first and most basic general contextual distinction is whether civil society operates in

a state or non-state context, or more widely in a failing or failed state context. The early debates

viewed civil society as either synonymous or inextricably intertwined with the state (Hobbes,

Locke). In more recent studies, while occupying the space between the state, the family and the

market, civil society is conceptualized as interacting with the state, both influencing and being

influenced by it . As such, the lines separating the state from civil society in practice remain

extremely blurred, complex and continuously renegotiated. Furthermore, many studies on nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) argue that these are often linked more to the state than to

society. The state thus inevitably shapes the nature and role of civil society.

This is even truer in the post-Cold War era, where often the legally recognized state is

failed or failing, while a functioning state structure remains in a legal limbo of international

non-recognition. When a state does not exist or is weak, fragmented or failing, the already

blurred lines separating the state from civil society become even fuzzier. Think about the cases

of Iraq or Syria today. But also think about the role of civil society organizations during the

regime changes during the so-called Arab spring in Tunisia or Egypt.

Think about the Ukrainian case of mobilization and polarization in the absence of the

state. The post-Maidan organizations ended up performing functions, like security and defense,

which the state has proved unable to fulfil. Civil society has become de facto a security actor

involved first in the provision of hard security, with the establishment of self-defense units

during the Maidan demonstrations and of volunteer battalions following the beginning of

hostilities in the east; second, in the procurement of military equipment for the troops and the

provision of logistical services (like medical or clerical work), even at the frontlines; and third,

in the monitoring and the oversight of defense-related issues and military operations in the

Donbas (Puglisi, 2015, 3). According to Ministry of Interior data, as of 1 January 2014, 3,713

civic formations had been established in the country with the purpose of protecting public

order. They comprised more than 76,000 members.

In situations such as these, civil society comes to occupy part of the space normally filled by

the functioning state. Controversial as it is, ISIS is radically replacing the state: taking up functions

previously performed by the governments of Iraq, Syria, and Libya such as the judiciary or education.

Without the laws and rules governing society, civil society organizes alternative systems of self-help

and tribal justice; informal forms of governance that civil and uncivil society actors alike establish

Valdai Papers #28. October 2015

CIVIL SOCIETY IN CONFLICTS: FROM ESCALATION TO MILITARIZATION

and are shaped by. When states are weak or failing, patronage, tribal affiliation, and often corruption

are likely to influence the nature and role of civil society. This is because civil society is induced to

fill the void left by the state by providing services to the population, yet doing so by interacting with

underground and illegal channels of the shadow state. Finally, where a recognized state exists but

lacks sovereignty and independence, civil society is often disempowered and de-responsibilized by

the absence of a sovereign interlocutor at state level.

Even when a state exists, a second contextual condition shaping civil society in conflict is

the actual nature of the state in question. In so far as civil society needs to be both permitted and

protected by the state, its existence, nature and role are determined by the degree of democracy,

delineating the extent of associative freedom, as well as by the existence of other basic rights

and freedoms normally enshrined within democratic states. When these rights and freedoms are

curtailed, civil society is likely to develop beyond legal boundaries, often aiming to subvert the

state rather than interact with it, thus problematizing further the distinction between civil and

uncivil society actors. Think about the revolutionary movements in the authoritarian regimes

in Latin America of the 70s and 80s or the dissidents in the USSR. Even within the confines

of formally democratic states, the shape of civil society is affected by the specific nature of

the democracy in question. In nationalistic states, civil society is more likely to include some

uncivil actors pursuing racial or xenophobic agendas. The spurge of nazi movements in

current Germany is a clear example, as well as the always significant presence of the Ku Klux

Kan (KKK) in the USA. In democracies with a strong military presence and militarized culture,

civil society is often associated with the push for democratization and the civilianization of

politics. In democracies founded upon a strong ideological consensus (e.g. Zionism for Israel,

Kemalism for Turkey), civil society acts in surveillance and critique of the state within clear

albeit un-spelt ideological confines, after which the socio-cultural reflex contracts and civil

society in unison with the state acts to counter real or perceived threats to the established

ideological order.

A third contextual condition in conflict situations is socio-economic underdevelopment,

which favors the presence of traditional over modern associational forms. Gellner (Gellner, 1995)

argues that whereas modularity characterizes civil society, segmentalism marks traditional

society. The modular society essentially exists in the developed world. It is characterized by

voluntarism and performs modern civic functions. By contrast, in a segmentalized society, often

found within developing contexts, civil society is characterized by a far more prominent role of

non-voluntary associations (family, tribe, ethnic or religious communities) over voluntary ones.

Often the bonds, loyalties and solidarity that these associative forms engender are far stronger

and more tenacious than those found in voluntary groupings. As such, while non-voluntary

associations in these contexts may curtail gender and other rights in the private sphere, they

also tend to be in a stronger position to carry out many of the modern functions normally

performed by civil society in developed contexts (e.g. the health and education services provided

by religious charities). Excluding these groups from the analysis would entail missing much of

the civil society activity in developing contexts. The African context is a clear example of the

relevance of the tribal affiliation in political and socio-economic terms.

The nature and role of the international community constitute a final contextual feature

shaping civil society. An overall global trend is traceable of states playing a diminishing role as

Valdai Papers #28. October 2015

CIVIL SOCIETY IN CONFLICTS: FROM ESCALATION TO MILITARIZATION

service providers both domestically and internationally, leading to the privatization of world

politics. Within this trend, a new global political opportunity structure has materialized in which

civil society actors have flourished both locally and transnationally. This has meant that many

of the functions previously performed by governmental actors have been reallocated to civil

society in the fields of development and security. Since the 1980s, development assistance has

been increasingly channeled through NGOs (Sogge, 1996). Developed states and international

organizations have outsourced the implementation of aid programs to local and international

NGOs, while mediating and retaining political discretion regarding overall direction (Fisher, 1997).

The more recent policy orientation for democracy promotion from western countries has also

heavily relied on the partnership with civil society organizations for the promotion of democracy

and human rights in third countries (Ottaway & Carothers, 2000). In a wide variety of cases, scholars

have demonstrated that by promoting particular types of civil society (e.g. NGOs, also dubbed

non-grassroots organizations), the donor community weakens civil society organizations (CSOs)

that have veritable ties to society and respond to local societal needs. The cases of Palestine or

Bosnia-Herzegovina are illustrative of this point. Donors also create a dislocated new civil society,

which is technical and specialized in mandate, neo-liberal in outlook, urbanized and middle

class in composition and responds to the goals of the international community rather than of

the society in question (Challand, 2008). Equally, the changing international security agenda has

shaped the nature and role of civil society. Since the 1990s, in view of the wave of humanitarian

interventions, many peacebuilding functions have been transferred to the private sector and civil

society (Brahimi Report, 2000; Goodhand, 2006; Richmond & Carey, 2005). Liberal humanitarian

and relief organizations, politically or financially coopted organizations and militarily embedded

organizations have mushroomed. Since the new millennium, the turn in global politics with

the global war on terror provided a further change in the role of (some) CSOs, through their

embeddedness and connivance with state-waged wars. Hence, while at times representing a

rooted and counter-hegemonic force of resistance, CSOs have also acted as a dependent functional

substitute within the neo-liberal paradigm. In more violent situation, external support in terms

of money or arms may prove essential. Consider the case of the financial support received by the

Maidan/Post Maidan movement in Ukraine (Weiss, 2015).

From conflict escalation to militarization

Another variable in our study of civil societys role in conflict is the framework of action

within which organizations operate. Central into this is the framework of conflict escalation

that may lead to the militarization of civil society. In conflicts, often a situation arise in which

groups, mostly self-defined in ethnic or religious terms, articulate their subject positions in

mutually incompatible ways. Once such incompatibility is publicly affirmed, this partisan

affiliations begin permeating unrelated sectors, organizations and activities, thus raising starkly

the stakes of divisive politics in society. As Horowitz (Horowitz, 1985, 12) puts it in the specific

cases of ethnic conflicts:

Valdai Papers #28. October 2015

CIVIL SOCIETY IN CONFLICTS: FROM ESCALATION TO MILITARIZATION

In divided societies, ethnic conflict is at the center of politics. Ethnic

divisions pose challenges to the cohesion of states and sometimes to peaceful

relations among states. Ethnic conflict strains the bonds that sustain civility and

is often at the root of violence that results in looting, death, homelessness and

the flight of large numbers of people. In divided societies, ethnic affiliations are

powerful, permeative, passionate and pervasive.

This progressive spread of partisan subject positions can result in split societies which are

conventionally divided in ranked and unranked systems (ibid.: 22). The distinction rests in the

possible overlap between social class, ideological orientation, religious affiliation, and ethnic

origin. In ranked systems ethnicity is strictly related to social class or caste structures. Linked to

this, a hierarchical ordering (associated with ranked systems) as opposed to a parallel ordering

(associated to unranked systems) of society also profoundly affects the development of conflict.

For instance, in ethnically ranked systems, when a single ethnic group dominates a powerful

public institution, the risk of that institution being used for ethnic purposes and discrimination

is high. In these circumstances, the tension between greed and grievance increases on the inside

and the scope for legal and institutionally negotiated accommodation falls, often leading to the

counter-mobilization of the discriminated group beyond legal and institutional boundaries. In

these cases, the discriminated group may engage in underground non-violent action or violent

action, shifting the conflict from latent to active stage.

Within this stage of conflict escalation the external dimension is also significant. Local

CoSOs may appeal to transnational norms in their quest to gain power and legitimacy, often in

coordination with third-party international and transnational CoSOs (Keck & Sikkink, 1998).

Think about the appeal to international norms used in East Timor or in South Sudan by political

and civil society actors. In so far as the victims are often denied access to local normative and

political resources, they are induced to appeal to external resources as the only means to

influence the local balance of power. This means conflicts often manifest themselves locally

through high-intensity intra-border tensions and violence and internationally by appealing to

laws and rights, which may be strategically used and at times manipulated to escalate conflict.

Think also the way the appeal to the international norm of self-determination is used by many

Tibetan activists. Consider the strong appeal to human right and anti-discriminatory principles

that the ANC anti-apartheid movement in South Africa aptly used in its fight. But think also

about the resistance movements in Italy during WWII and the end of the fascist regime: the

partigiani appealed to anti-authoritarian values recognized by the international community

and thanks to that they secured a crucial support.

In these situations, local, international and transnational CoSOs can play a crucial role

in the successive phases of conflict eruption and escalation. They can discursively contribute to

the securitization of conflict by raising awareness of conditions of latent conflict through mass

demonstrations, media diffusion, public assemblies, monitoring and denouncing activities. They

can also ignite conflict in its violent stages by organizing and activating combatant groups and

guerrillas (e.g. the fighters in the Donbass region or the guerrilla action by Sendero Luminoso in

Per). At the international level, they can call for indirect support through funds and arms, or lobby

for the direct involvement of the international community in the conflict (e.g. through mediation

or war) (e.g. the rebels in Syria and their continuous appeal for an international intervention).

Valdai Papers #28. October 2015

CIVIL SOCIETY IN CONFLICTS: FROM ESCALATION TO MILITARIZATION

Mechanisms of politicization

Civil mobilization is often carried out through the radicalization of political identities.

Conflicts have been defined as a struggle between peoples, often self-defined in ethnic terms,

who articulate their respective needs and wants in mutually incompatible ways. As opposed to

peace, conflict (defined as an incompatibility of subject positions) can either not be manifested

publicly at all, i.e. in conditions of latent structural violence, or it can be manifested through

violence or non-violent means (e.g. political activism). The source of the incompatibility is

inextricably tied to the very definition of the group: an ethnic definition which is politically

constructed as primordial, non-voluntary and exclusive in nature and defines itself in contrast to

an external other. Ethno-political conflicts are in fact characterized by a public discord either

between the state and significant parts of society or between different parts of the population.

The discord and division are claimed on the grounds of identity defined through ethnicity:

a multiple concept that refers to a myth of collective ancestry. Central to this concept is the

notion of ascription and affinity. Ethnic identification is thus often based on the prioritization

of birth over territory (think about the ethnicization of the Kurdish issue in Turkey by the PKK,

or the conflicts in Norther Ireland, the Basque Countries, or in Sdtirol).

In this context, an important determinant is the identity of CoSOs is the degree of

inclusiveness of membership and of the targeted public. Roughly speaking, the two extremes are

an inclusive and universalistic approach and an exclusive and particularistic one. Either a group

is open to accept as members or receiving agents all those involved in conflict, or it focuses only

on a limited section of the population demarcated by ethnic boundaries. An inclusive outlook

entails either the promotion of a single cultural identity or the creation of a civic or multitiered

hybrid identity. An exclusive outlook bases its approach on the existence of primordial and

unchanging identities. Another fundamental variable characterizing CoSO identities is their

egalitarian or non-egalitarian nature. An egalitarian CoSO accepts as equal all actors across the

conflict divide, while a non-egalitarian approach attempts to assert the primacy of one group

over another. If we combine these two variables, we can identify four main CoSO identities

determining their overall normative outlook on the conflict. Needless to say, these identities are

stylized, and in reality most CoSOs will display different combinations, changing over time. Yet

marking such distinctions provides a necessary frame of reference to understand the identities

of the actors in question.

A civic or post-national identity emerges from CoSOs with an inclusive and egalitarian

outlook. Contrary to other categories, this is the only identity that places primary emphasis on

the individual. It thus promotes either a liberal civic (as opposed to ethnic) identity or it accepts

and fosters multiple identities freely chosen by each individual. These groups may include

international NGOs with a liberal civic outlook, such as Human Rights Watch, Mdecins Sans

Frontires (MSF) or Amnesty International, or local bi-communal groups such as Women in

Black in Israel-Palestine or the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) Cyprus Centre in Nicosia.

While these groups are normally associated with peacemaking functions, they may also, at

times necessarily, escalate conflicts through their securitizing moves, by voicing, monitoring

and denouncing previously silenced and repressed facts.

A multiculturalist CoSO is one which, while accepting the right of all actors to an equal

footing, recognizes and values their different cultural identities rather than attempting to

transcend them. These may include inter-cultural movements or organizations (e.g. the

Valdai Papers #28. October 2015

CIVIL SOCIETY IN CONFLICTS: FROM ESCALATION TO MILITARIZATION

Tres Culturas Foundation in Sevilla) or inter-religious gatherings (such as the Day of the

Prayer in Assisi, inter-faith dialogues for Middle East peace and the Dialogue of Civilizations

promoted by former Iranian president Khatami). Especially when inter-religious groups

at international levels highlight and denounce the non-egalitarian treatment of specific

communities within conflict contexts, they may raise, at times necessarily, awareness and

induce the counter-mobilization of discriminated communities. These movements can be

either litist or grassroots.

An assimilationist CoSO is one which accepts the ideal of promoting an undivided

society, but does so in a non-egalitarian fashion by promoting a homogeneous society in

which the dominant ethnic group asserts its own identity over the others. These may include

militant groups such as the Grey Wolves in Turkey, which, while highlighting the importance of

Turkishness over and above other identities, is prepared to accept and encourage the assimilation

of other groups into the Turkish nation. If others comply they are accorded equal treatment

within the state. While different in terms of strategies and actions, other assimilationist groups

and practices include born-again Christians in the United States, Islamist fundamentalists and

the practice of ethnic rape in war.

Finally, the racist/ethnicist CoSO is exclusive and non-egalitarian in outlook, believing

in the primacy of a single and primordially given and thus non-assimilable identity. It advocates

either ethnic cleansing or an effective apartheid system with permanent second-class citizenship.

Examples include far-right Israeli transfer movements (i.e. Amihai) calling for the expulsion of

the Palestinians to neighbouring Arab countries, the Ku Klux Klan in the United States and the

Australian Holocaust-denying Adelaide Institute.

Beyond the original context in which CoSOs operate, their identities and their

frameworks of action, a final elements needed to understand the mechanisms of mobilization

is the political opportunity structure (POS) in which they operate. Rather than acting as a

factor in itself, the POS is the filter during the successive phases of conflict which shapes

the impact of CoSO actions. While related to the conflict context categories analyzed above,

the POS factors remain distinct from them in terms of their role rather than their nature.

They deal with domestic institutions (linked to the existence and nature of a state, the

degree and type of democracy), with domestic development (linked to the level of socioeconomic development) and with external actors (linked to the international presence). Yet

the key distinguishing feature of the POS, as opposed to the original contextual categories,

is that of timing. This is because time, as opposed to the original conflict situation, impinges

dynamically on the impact of CoSOs on conflicts.

A first structural feature determining the POS is timing. In phases of violent and

escalating conflict, in which subject positions are polarized, the conflict-fuelling impact of

assimilationist and racist/ethnicist CoSOs is likely to be more effective than any attempt by

civic or multiculturalist CoSOs to rearticulate conflict identities and objectives. There is not

necessarily a particular approach or action which by definition is more effective, but a fitting

coincidence of right action and right timing. Effectiveness is thus conditioned by the precise

moment in which the action is carried out.

10

Valdai Papers #28. October 2015

CIVIL SOCIETY IN CONFLICTS: FROM ESCALATION TO MILITARIZATION

Two further structural features are linked to the domestic context. One is the existence

and nature of the domestic institutional system in the conflict context. This includes the design

of both the constitutional and legal setting and the set of public institutions and the actors

operating within them (e.g. political parties). For example, the presence of constitutionally

entrenched and legally protected associational freedom or the supportive attitude of the

authorities shapes the nature and actions of a CoSO and its ensuing impact upon an evolving

conflict. The cases of Georgia and Russia illustrate two sides of the same coin. In Georgia, in

the early post-Rose Revolution period in 2004, a set of reforms were passed to ease civil society

activity (e.g. facilitating registration procedures and reducing tax burdens), although the tight

relationship between the Saakashvili regime and civil society reduced the independence and

thus the popular appeal of the latter. By contrast, in Russia the 2006 Law on NGOs setting

bureaucratically tight and financially onerous requirements for the registration of NGOs have

seriously curtailed the space for internationally funded civic and multicultural civil society

actors.

Another domestic feature is the level of overall development, including in economic,

political, social and cultural spheres. Hence, for example, the degree to which public opinion

is open to non-governmental political action and protest can significantly influence the

wider diffusion and consolidation effects of CoSOs. On the positive side, southern Cyprus in

the post-1974 period experienced a sustained economic boom which led to the development

and transformation of civil society. On the negative side, the progressive de-development of

the Palestinian occupied territories during the Oslo period, particularly since the outbreak of

the second Intifada, reduced the scope for a flourishing independent civil society. This was

aggravated further by the inflow of Western funds, which weakened the indigenous civil society

domain while cultivating a coopted yet ineffective NGO sector (Le More, 2008).

A final structural feature constituting the POS is the role of the international system

and the actors operating within it. Hence in a situation in which the international community

converges on war, pacifist CoSOs find themselves marginalized, while combatant groups gain

the necessary political and material support for their actions to be effective. The conflict in

Kosovo is an evident case in point, whereby nationalist Kosovo CoSOs were legitimized by

the Western support for Kosovo against Serbia, culminating in the recognition of Kosovos

independence in 2008. Alternatively, pacifist CoSOs may enhance their impact by allying

with international forces opposing a war, repression or discrimination. For example, several

diaspora Tibetan groups effectively mobilized the international community in the wake of

the summer 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing to support the Tibetan cause and exert pressure

on Beijing. Yet often the interrelationship between international involvement and CoSOs

works in the opposite direction, whereby rather than CoSOs being strengthened by an

international alliance, their search for international support alters their very raison detre.

Beyond the case of Palestinian civil society mentioned above, another notable example is

Bosnia-Herzegovina, where the strong international and EU presence post-Dayton Accords

profoundly affected the nature, actions and mode of operation of local civil society actors

wishing to win the political and financial support of international actors. The internationallocal dynamics remain a key factor in understanding the political mobilization of CoSOs

action.

Valdai Papers #28. October 2015

11

CIVIL SOCIETY IN CONFLICTS: FROM ESCALATION TO MILITARIZATION

Conclusion

The cumulative interaction between context, identity, frameworks of action and political

opportunity structures determines CoSOs impact on conflict. Impact is taken to mean both

the direct results of a particular action (e.g. providing refugee relief) and the influence on

the wider context underlying a particular manifestation of conflict (e.g. strengthening the

international legal framework that ensures the protection of refugee rights and their right of

return). CoSOs direct and contextual impact is determined by the wider conflict context; by

the identities of CoSOs; by their actions within the four main frameworks of action; and by

the political opportunity structure within which they operate. The identities and actions of

CoSOs are influenced by, while at the same time influencing, the economic, political, social,

cultural and legal context within which they operate. A spiral causal chain can thus be stylized

as follows. Context shapes the identities of CoSOs. These identities determine their goals and

frameworks of actions. In turn, the ability of CoSOs to navigate the political opportunity

structure of conflicts critically shaped by the original conflict context determines their

overall direct and contextual impact; the latter of which feeds back into the original conflict

context.

References

12

1.

Brahimi Report. (2000). Report of the Panel on United Nations Peace Operations. New York:

United Nations, A/44/305, S/2000/809.

2.

Buzan, B., Wver, O., & De Wilde, J. H. (1998). Security. A New Framework For Analysis. Boulder

and London: Lynne Rienner.

3.

Challand, B. (2008). Palestinian Civil Society: Foreign Donors and the Power to Promote and Exclude. London: Routledge.

4.

Chambers, S., & Kopstein, J. (2001). Bad Civil Society. Political Theory, 29(6), 837-886.

5.

Chandler, D. G. (2001). The Road to Military Humanitarianism: How the Human Rights NGOs

Shaped a New Humanitarian Agenda. Human Rights Quarterly, 23(3), 678-700.

6.

Douma, N., & Klem, B. (2004). Civil War and Civil Peace. A Literature Review of the Dynamics

and Dilemmas of Peacebuilding through Civil Society: Netherlands Institute of International Relations Clingedael.

7.

Fisher, W. F. (1997). Doing Good?: The Politics and Antipolitics of NGO Practices. Annual Review

of Anthropology, 26, 439-464.

8.

Forster, R., & Mattner, M. (2006). Civil Society and Peacebuilding. Potential, Limitations and

Critical Factors. Washington, DC: World Bank, Social Development Dept., Sustainable Development Network.

9.

Gellner, E. (1995). The Importance of Being Modular. In J. Hall (Ed.), Civil Society: Theory, History and Comparison. Cambridge: Blackwell.

Valdai Papers #28. October 2015

CIVIL SOCIETY IN CONFLICTS: FROM ESCALATION TO MILITARIZATION

10. Goodhand, J. (2006). Aiding Peace? The Role of NGOs in Armed Conflict. Bourton on Dunsmore,

Rugby: ITDG Publishing.

11. Horowitz, D. L. (1985). Ethnic Groups in Conflict. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

12. Kaldor, M., & Muro-Ruiz, D. (2003). Religious and Nationalist Militant Groups. In M. Kaldor, H.

K. Anheier & M. Glausius (Eds.), Global Civil Society 2003 (pp. 151-184). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

13. Keck, M., & Sikkink, K. (1998). Activists Beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International

Politics. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

14. Le More, A. (2008). International Assistance to the Palestinians after Oslo: Political Guilt, Wasted Money. London: Routledge.

15. Marchetti, R., & Tocci, N. (Eds.). (2011a). Civil Society, Ethnic Conflicts, and the Politicization of

Human Rights. Tokyo: United Nations University Press.

16. Marchetti, R., & Tocci, N. (Eds.). (2011b). Conflict Society and Peacebuilding. New Delhi: Routledge.

17. Ottaway, M., & Carothers, T. (Eds.). (2000). Funding Virtue: Civil Society Aid and Democracy

Promotion. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

18. Puglisi, R. (2015). A Peoples Army: Civil Society as a Security Actor in Post-Maidan Ukraine IAI

working paper series 15. Rome: IAI.

19. Richmond, O. (2005). The Transformation of Peace. Aldershot: Palgrave.

20. Richmond, O., & Carey, H. (2005). Subcontracting Peace: The Challenges of NGO Peacebuilding.

Aldershot: Ashgate.

21. Sogge, D. (Ed.). (1996). Compassion and Calculation. The Business of Private Foreign Aid. London: Pluto Press.

22. Weiss, M. (2015). Crowdfunding the war in Ukraine - From Manhattan. Foreign Policy, 4.

Valdai Papers #28. October 2015

13

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Sap EwmDocumento2 pagineSap EwmsirivirishiNessuna valutazione finora

- Strategic Depth in Syria - From The Beginning To Russian InterventionDocumento19 pagineStrategic Depth in Syria - From The Beginning To Russian InterventionValdai Discussion Club100% (1)

- Native Instruments Sibelius Sound Sets - The Sound Set ProjectDocumento3 pagineNative Instruments Sibelius Sound Sets - The Sound Set ProjectNicolas P.Nessuna valutazione finora

- Reflecting On The Revolution in Military Affairs: Implications For The Use of Force TodayDocumento14 pagineReflecting On The Revolution in Military Affairs: Implications For The Use of Force TodayValdai Discussion ClubNessuna valutazione finora

- WAM ES Screw Conveyors Manual JECDocumento43 pagineWAM ES Screw Conveyors Manual JECabbas tawbiNessuna valutazione finora

- Pedagogical Leadership. Baird - CoughlinDocumento5 paginePedagogical Leadership. Baird - CoughlinChyta AnindhytaNessuna valutazione finora

- Regionalisation and Chaos in Interdependent World Global Context by The Beginning of 2016Documento13 pagineRegionalisation and Chaos in Interdependent World Global Context by The Beginning of 2016Valdai Discussion ClubNessuna valutazione finora

- Сentral Аsia: Secular Statehood Challenged by Radical IslamDocumento11 pagineСentral Аsia: Secular Statehood Challenged by Radical IslamValdai Discussion ClubNessuna valutazione finora

- Lessons of The Greek TragedyDocumento15 pagineLessons of The Greek TragedyValdai Discussion ClubNessuna valutazione finora

- Prospects For Nuclear Power in The Middle East: Russia's InterestsDocumento76 pagineProspects For Nuclear Power in The Middle East: Russia's InterestsValdai Discussion ClubNessuna valutazione finora

- WAR AND PEACE IN THE 21st CENTURY: International Stability and Balance of The New TypeDocumento15 pagineWAR AND PEACE IN THE 21st CENTURY: International Stability and Balance of The New TypeValdai Discussion ClubNessuna valutazione finora

- ISIS As Portrayed by Foreign Media and Mass CultureDocumento23 pagineISIS As Portrayed by Foreign Media and Mass CultureValdai Discussion ClubNessuna valutazione finora

- Jeremy Corbyn and The Politics of TranscendenceDocumento12 pagineJeremy Corbyn and The Politics of TranscendenceValdai Discussion ClubNessuna valutazione finora

- Valdai Paper #36: The Legacy of Statehood and Its Looming Challenges in The Middle East and North AfricaDocumento14 pagineValdai Paper #36: The Legacy of Statehood and Its Looming Challenges in The Middle East and North AfricaValdai Discussion Club100% (1)

- The Background and Prospects of The Evolution of China's Foreign Strategies in The New CenturyDocumento15 pagineThe Background and Prospects of The Evolution of China's Foreign Strategies in The New CenturyValdai Discussion ClubNessuna valutazione finora

- Valdai Paper #38: The Network and The Role of The StateDocumento10 pagineValdai Paper #38: The Network and The Role of The StateValdai Discussion ClubNessuna valutazione finora

- Governance For A World Without World GovernmentDocumento11 pagineGovernance For A World Without World GovernmentValdai Discussion ClubNessuna valutazione finora

- Valdai Paper #32: The Islamic State: An Alternative Statehood?Documento12 pagineValdai Paper #32: The Islamic State: An Alternative Statehood?Valdai Discussion ClubNessuna valutazione finora

- Agenda For The EEU EconomyDocumento15 pagineAgenda For The EEU EconomyValdai Discussion ClubNessuna valutazione finora

- Valdai Paper #33: Kissinger's Nightmare: How An Inverted US-China-Russia May Be Game-ChangerDocumento10 pagineValdai Paper #33: Kissinger's Nightmare: How An Inverted US-China-Russia May Be Game-ChangerValdai Discussion ClubNessuna valutazione finora

- The Prospects of International Economic Order in Asia Pacific: Japan's PerspectiveDocumento9 pagineThe Prospects of International Economic Order in Asia Pacific: Japan's PerspectiveValdai Discussion ClubNessuna valutazione finora

- Valdai Paper #29: Mafia: The State and The Capitalist Economy. Competition or Convergence?Documento12 pagineValdai Paper #29: Mafia: The State and The Capitalist Economy. Competition or Convergence?Valdai Discussion Club100% (1)

- Multilateralism A La Carte: The New World of Global GovernanceDocumento8 pagineMultilateralism A La Carte: The New World of Global GovernanceValdai Discussion ClubNessuna valutazione finora

- Valdai Paper #31: Another History (Story) of Latin AmericaDocumento10 pagineValdai Paper #31: Another History (Story) of Latin AmericaValdai Discussion ClubNessuna valutazione finora

- Discipline and Punish Again? Another Edition of Police State or Back To The Middle AgesDocumento10 pagineDiscipline and Punish Again? Another Edition of Police State or Back To The Middle AgesValdai Discussion ClubNessuna valutazione finora

- Geopolitical Economy: The Discipline of MultipolarityDocumento12 pagineGeopolitical Economy: The Discipline of MultipolarityValdai Discussion ClubNessuna valutazione finora

- High End Labour: The Foundation of 21st Century Industrial StrategyDocumento13 pagineHigh End Labour: The Foundation of 21st Century Industrial StrategyValdai Discussion ClubNessuna valutazione finora

- The Future of The Global Trading SystemDocumento8 pagineThe Future of The Global Trading SystemValdai Discussion ClubNessuna valutazione finora

- Just War and Humanitarian InterventionDocumento12 pagineJust War and Humanitarian InterventionValdai Discussion ClubNessuna valutazione finora

- Reviving A Species. Why Russia Needs A Renaissance of Professional JournalismDocumento7 pagineReviving A Species. Why Russia Needs A Renaissance of Professional JournalismValdai Discussion ClubNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Commons: A New Alternative To NeoliberalismDocumento8 pagineSocial Commons: A New Alternative To NeoliberalismValdai Discussion Club100% (1)

- The Social Roots of Islamist Militancy in The WestDocumento8 pagineThe Social Roots of Islamist Militancy in The WestValdai Discussion ClubNessuna valutazione finora

- After American Hegemony and Before Global Climate Change: The Future of StatesDocumento9 pagineAfter American Hegemony and Before Global Climate Change: The Future of StatesValdai Discussion ClubNessuna valutazione finora

- Activity 2Documento5 pagineActivity 2DIOSAY, CHELZEYA A.Nessuna valutazione finora

- OOPS KnowledgeDocumento47 pagineOOPS KnowledgeLakshmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Assistant Bookkeeper Resume Sample - Best Format - Great Sample ResumeDocumento4 pagineAssistant Bookkeeper Resume Sample - Best Format - Great Sample ResumedrustagiNessuna valutazione finora

- Workplace Risk Assessment PDFDocumento14 pagineWorkplace Risk Assessment PDFSyarul NizamzNessuna valutazione finora

- 3.1 MuazuDocumento8 pagine3.1 MuazuMon CastrNessuna valutazione finora

- Package-Related Thermal Resistance of Leds: Application NoteDocumento9 paginePackage-Related Thermal Resistance of Leds: Application Notesalih dağdurNessuna valutazione finora

- Jazz PrepaidDocumento4 pagineJazz PrepaidHoney BunnyNessuna valutazione finora

- N6867e PXLP 3000Documento7 pagineN6867e PXLP 3000talaporriNessuna valutazione finora

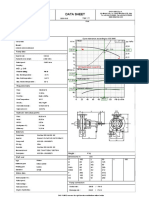

- Data Sheet: Item N°: Curve Tolerance According To ISO 9906Documento3 pagineData Sheet: Item N°: Curve Tolerance According To ISO 9906Aan AndianaNessuna valutazione finora

- AE HM6L-72 Series 430W-450W: Half Large CellDocumento2 pagineAE HM6L-72 Series 430W-450W: Half Large CellTaso GegiaNessuna valutazione finora

- Using Impact IX49 and 61 With Nektar DAW Integration 1.1Documento21 pagineUsing Impact IX49 and 61 With Nektar DAW Integration 1.1Eko SeynNessuna valutazione finora

- Changing Historical Perspectives On The Nazi DictatorshipDocumento9 pagineChanging Historical Perspectives On The Nazi Dictatorshipuploadimage666Nessuna valutazione finora

- 1974 - Roncaglia - The Reduction of Complex LabourDocumento12 pagine1974 - Roncaglia - The Reduction of Complex LabourRichardNessuna valutazione finora

- Validación Española ADHD-RSDocumento7 pagineValidación Española ADHD-RSCristina Andreu NicuesaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ge 6 Art Appreciationmodule 1Documento9 pagineGe 6 Art Appreciationmodule 1Nicky Balberona AyrosoNessuna valutazione finora

- Aerated Concrete Production Using Various Raw MaterialsDocumento5 pagineAerated Concrete Production Using Various Raw Materialskinley dorjee100% (1)

- Column Buckling TestDocumento8 pagineColumn Buckling TestWiy GuomNessuna valutazione finora

- TOA Project Presentation (GROUP 5)Documento22 pagineTOA Project Presentation (GROUP 5)Khadija ShahidNessuna valutazione finora

- DICKSON KT800/802/803/804/856: Getting StartedDocumento6 pagineDICKSON KT800/802/803/804/856: Getting StartedkmpoulosNessuna valutazione finora

- Aquinas Five Ways To Prove That God Exists - The ArgumentsDocumento2 pagineAquinas Five Ways To Prove That God Exists - The ArgumentsAbhinav AnandNessuna valutazione finora

- 2022 Summer Question Paper (Msbte Study Resources)Documento4 pagine2022 Summer Question Paper (Msbte Study Resources)Ganesh GopalNessuna valutazione finora

- ADAMS/View Function Builder: Run-Time FunctionsDocumento185 pagineADAMS/View Function Builder: Run-Time FunctionsSrinivasarao YenigallaNessuna valutazione finora

- Review Rachna WasteDocumento9 pagineReview Rachna WasteSanjeet DuhanNessuna valutazione finora

- U2 LO An Invitation To A Job Interview Reading - Pre-Intermediate A2 British CounciDocumento6 pagineU2 LO An Invitation To A Job Interview Reading - Pre-Intermediate A2 British CounciELVIN MANUEL CONDOR CERVANTESNessuna valutazione finora

- Classroom Debate Rubric Criteria 5 Points 4 Points 3 Points 2 Points 1 Point Total PointsDocumento1 paginaClassroom Debate Rubric Criteria 5 Points 4 Points 3 Points 2 Points 1 Point Total PointsKael PenalesNessuna valutazione finora

- Num Sheet 1Documento1 paginaNum Sheet 1Abinash MohantyNessuna valutazione finora