Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Editorial Preface: The Case For Case-Based Research

Caricato da

ammoj850Titolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Editorial Preface: The Case For Case-Based Research

Caricato da

ammoj850Copyright:

Formati disponibili

The Case for Case-Based Research

Steven Gordon

Journal ofInformation Technology Case andApplication Research; 2008; 10, 1; ABVINFORM Global

Pg. 1

The Case for Case-Based Research

Editorial Preface

The Case for Case-Based Research

Steven Gordon

Editor-in-Chief

Babson College, Babson Park, MA 02457

pordon @ babson.edu

SETTING THE SCENE

JITCAR was founded by Shailendra Palvia in 1999 in response to an impression among

researchers that publishing high-quality case-based research in the major journals in our field was

difficult and becoming increasingly so (Palvia, 1999). Dub6 and Par6 (2003) document that

between 1990 and 1999, case articles accounted for only 15 percent of manuscripts published in

the seven journals that they identified as the top outlets for information systems (IS) research.

Additionally, case research was the primary research technique in only 80 percent of these

articles, or 12 percent of the total.

Fast forward nine years to the present. The top IS journals other than JITCAR continue to

publish a low percentage of case-based research. Furthermore, in the on-going discussion about

relevance versus rigor in our discipline (see, for example, King and Lyytinen, 2006; Desouza et

al., 2006; Klein and Hirschheim, 2003), case research is typically viewed as low in rigor.

Skeptics ask, "How can lessons be generalized from a sample of one?'and, consequently, "What

value can be extracted from case-based research?"

RIGOR IN CASE RESEARCH

Before answering these questions, it is useful to define what we mean by "rigor" in the context of

academic research. In the physical sciences before the early 1900s, rigor typically implied two

things: 1) that an experiment showed what it was intended to show, i.e., that there were no

unidentified factors that could have caused the observed effects; and 2) that the experiment was

described sufficiently well as to be repeatable by other scientists. Because of the latter

requirement, the concept of "rigor" became tightly entwined with accuracy of measurement. The

advent of quantum mechanics forced a redefinition of rigor because quantum events could not be

replicated with certainty. A particle could be found in one place or another, but its location could

be specified only by a probability distribution. Similarly, in the biological sciences,

reproducibility exists only at a statistical level. A drug might be effective in 99.9% of the patients

who take it, but its degree of effectiveness and the ideal dosage varies among individual patients.

For some patients, the drug might not work at all and might even have negative or dangerous side

effects. Eliminating alternative causes for observed effects is also more difficult in the biological

sciences than in the physical sciences. As a result, rigor in the biological sciences requires

JITCAR, Volume 10, Number 1, 2008

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

The Case for Case-Based Research

methodologies to control for variability in the biological systems and their environments and to

address the statistical validity of observed results.

In the social sciences, including management disciplines such as management information

systems, research is hampered by the inherent complexity of the systems being investigated.

Social systems are orders of magnitude more complex than biological systems. In most real

social systems, hundreds of variables, most beyond the control of the investigator, change

simultaneously. In addition, the subjects of experiments cannot be directly manipulated as they

often are in physical or biological experiments. Furthermore, many of the underlying variables of

interest, such as personality traits, motivation, and fear of change cannot be directly observed.

Instead, they are implied by observable indicators or measurable surrogate factors that

presumably correlate with the variable or variables of interest. As a result, deficiencies exist even

in research that is as rigorous as possible in the traditional sense. Specifically, it is impossible to

control for or assess the impact of all of the factors that could affect what is ultimately observed.

And, the impact of an independent variable on the dependent variable can be predicted only with

a low degree of statistical certainty. There may be a high degree of certainty that the independent

variable has some impact (that is, the coefficient of the variable in an equation is statistically

significant), but, because social systems are so complex, rarely is the magnitude of the impact

known with any degree of certainty.

It is interesting to explore how case-based research compares to statistical research according to

our original definition of rigor: 1) that the research shows what it intends to show; and 2) that the

experiment is described in sufficient detail as to be repeatable. I will argue that both research

methodologies can be rigorous, but that they take different paths to achieving rigor and, by

necessity, define rigor differently.

In assessing the rigor of a particular research effort, it is important to ask if the research shows

what it intends to show. For both statistical and case-based research, the research question must

be stated clearly and unambiguously. But, the nature of research questions in quantitative,

statistical studies differs implicitly from those of case-based studies. Statistical research asks

whether hypothesized relationships exist in a statistical sense. If such relationships are shown to

exist, it cannot be inferred that they will exist for a particular organization or in a particular

context. Case-based research, in contrast, asks whether hypothesized relationships exist in a

given context. If such relationships are shown to exist, it cannot be inferred that they will exist in

any other context.

In assessing rigor, we must also ask if the experiment is sufficiently well described as to be

repeatable. In statistical studies, this requires describing how the subjects were selected, what

instruments were used to measure the variables of interest, and what statistical methods were used

to test the hypothesized relationships. For case-based research, this requires describing how the

subject or subjects were selected, what observational techniques andlor instruments were used to

measure the important variables, and how the data were analyzed to demonstrate the hypothesized

relationships. In both methodologies, different researchers analyzing the same data should be

able to reach the same conclusions.

JlTCAR, Volume 10, Number 1,2008

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

The Case for Case-Based Research

It is worth noting that not all case-based research follows a positivistic philosophy, which holds

that laws of causation exist and can be deduced by following scientific principles. Information

systems case researchers have also followed other philosophies, sometimes labeled "critical" or

"interpretive" (see Klein and Myers, 1999). Critical research seeks to focus the reader's attention

on social injustice or evil so as to improve social or working conditions, enhance productivity, or

increase the value of information systems and technology. Interpretive research operates on the

philosophy that reality is in the mind of the beholder. Phenomena are understood differently by

different people, and reality is an interpretation of what has been seen or heard. The value of

such research lies more in understanding complex social and organizational phenomena from

multiple perspectives than in drawing or proving hypotheses. JITCAR will accept interpretive

cases if interpretive principles, such as those advocated by Klein and Myers (1999). are

appropriately followed.

RELEVANCE IN CASE RESEARCH

Case-based and statistical research studies are different but complementary in the nature of their

relevance. The relevance of statistical research depends in large part on how much of the

variance in the dependent variable can be explained by the independent variables. In information

systems studies, this percentage is often low. Top-ranked journals, such as MIS Quarterly and

Information Systems Research, regularly present models in which less than 15% of the variance is

explained or in which the authors extol the significance of an added variable that changes the

percent of variance explained by less than 10%. Very few studies present models that explain as

much as 50% of the variance in the dependent variable. Therefore, practitioners have a hard time

assessing whether statistical research is applicable to their individual contexts. While an

executive might expect to obtain a desired change by manipulating the independent variable in

his or her organization, he or she cannot be confident that the change will occur at all, and it is

quite possible that change will occur in a direction counter to what is desired.

The relevance of case-based research depends in large part on how well the context of its

intended use matches the context of the research case. If the case is adequately descriptive,

executives and other managers should be able assess the quality of this match. For some, the case

will have no value. Others might say, "This case could have been written about my organization

and my situation." They might justifiably feel confident that they can obtain the same impact by

following the same actions as those described in the case. Most others will find themselves

somewhere between these two extremes. Differences in organizational structure, culture,

location, size, business practices and other factors will require them to examine how their

outcomes will be affected by differences between their environment and that described by the

case.

Because of these differences in how statistical and case-based studies are applied, case study

research increases the relevance of statistical research in the same domain and vice versa.

Someone who would like to emulate the protagonist of a case to produce a similar outcome will

feel more confident if statistical studies support that outcome, even if his or her situation is

somewhat different from that described in the case. Similarly, someone attempting to manipulate

independent variables corresponding to a statistical study will gain confidence if a case study

supporting the statistical research provides a parallel to his or her situation. Case studies that

JITCAR, Volume 10, Number 1, 2008

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

The Case for Case-Based Research

provide counter-evidence to the results of statistical studies are equally valuable because they

help identify situations for which theory based on statistical observation does not or may not

apply. Researchers often fail to consider the case study method as a means for testing theory.

Jans and Dittrich (2008) found only 23 theory-testing cases in a sample of 689 cases in five fields

of business research published between 2000 and 2005 in top journals. Yet, the value of a case

study in confirming or disconfirming theory cannot be denied.

Case research is most commonly conceived, and perhaps most appropriately applied, in theory

exploration and development (Benbasat et al., 1987). This is good news for case researchers

because business theory is, for the most part, highly nuanced and in constant development.

Statistical research for theory development is hampered by the "curse of dimensionality." It is

impossible to account for or control all the variables that interact in a normal business

environment without analyzing an impossibly large number of cases or observations. In casebased research, however, any factor can be observed and its impact traced, in time and in state, to

document its effect and to bring nuance to existing theory. It might be impossible to "prove" that

A affects B, but a case can document what happens as A occurs and can demonstrate, following a

chain of events, how it might ultimately affect B.

SETTING THE BAR

In view of the arguments presented above, how should the editors of JITCAR judge the quality of

a case-based research manuscript? I believe that the following requirements should be met:

1. The research question or questions must be clearly stated;

2. The research questions must be well motivated;

3. Prior research relevant to the questions of interest must be addressed;

4. The context of the case must described sufficiently well as to provide confidence in

repeatability; and

5. The evidence in the case and the processes of data collection and analysis must provide

answers to the research questions with appropriate caveats.

Below we examine each of these requirements in turn. A more formal and complete explication

of appropriate research methods and presentation can be found in Yin (2003).

Stating the research question clearly is the first step in providing rigor. It allows the readers and

reviewers to determine whether the case demonstrates what it intends to demonstrate. In

exploratory and theory-building research, the questions should be framed very broadly, as in

"How does A affect B?', "Why does A affect B?', or even "What affects B ? ' I n theory-testing

cases, the research question should be framed much more narrowly, as in "Does Theory X Apply

in Context Y."

Two components are necessary to motivate the research. The first is plausibility. If you intend to

ask how A affects B, you must first show that it is plausible for A to affect B. Plausibility may

not be of great concern in the earliest, exploratory stages of theory building, when you are simply

asking "What affects B?', but where theory already exists to explain the causes of B, the case

researcher is obliged to address why the research question even merits the reader's attention. The

second component is value. Why should the reader care? The researcher needs to make the case

that the answer is important in a variety of contexts, the more the better.

JITCAR, Volume 10, Number 1, 2008

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

The Case for Case-Based Research

A review of relevant research establishes whether the case builds or tests theory. If prior research

provides answers to the research question, then the case should be framed as theory-testing

research. If prior research is incomplete in the sense that it cannot provide answers to the

research question, the case researcher should demonstrate that multiple, different answers to the

case question conform to existing theory. Such a demonstration establishes value by proving that

the case supplements existing theory.

Case research is not strictly repeatable. So, there must be enough detail in the case to allow the

reader to predict with some certainty how likely it would be for the same effects to be observed if

the same actions were taken in similar situations. This requires the case to provide depth in

describing the context. It also requires the case to show, to the extent possible, a chain of

causality between the independent variables, or actions taken by the case protagonists, and the

dependent variable, which is the outcome observed. While statistical research can imply

causality with some repeatability in similar populations, case research can more clearly and

believably demonstrate causality and, implicitly, repeatability. Description of the data collection

and analysis processes is also important to provide evidence that the conclusions are unbiased.

Finally, the evidence in the case should provide answers to the research questions with

appropriate caveats. This closes the loop and demonstrates the value of the case. This

requirement is closely linked to demonstrating a chain of causality. To the extent that the reader

can follow the causal chain and relate cause and effect to the research question, he or she will

believe that the research question has been answered. Nevertheless, as questions in the social

sciences rarely have a black and white answer, caveats are important. The researcher must

address what factors besides those addressed by the research question could have caused the

observed effects.

CONCLUSION

In concluding, the questions posed at the start of this essay can now be answered. "How can

lessons be generalized from a sample of one?' I hope to have argued persuasively that research

on a sample of one can, if done properly, explore questions of interest, help develop new theory,

lend weight to existing theory, and disconfii existing theory or strongly held hypotheses.

"What value can be extracted from case-based research?'Its value derives from its ability to

build and test theory plus its power to provide practitioners with the capacity to assess whether

existing or newly-developed theory is applicable to their particular needs.

As I take the reins of JITCAR's leadership from Dr. Palvia, I want to thank him for his insight

and tireless work in creating a highly recognized publication outlet for serious case researchers. I

am mindful of JITCAR's mission to promote case-based research in IS and hope, during my term

as Editor-in-Chief, to continuously improve the rigor and relevance of the manuscripts we

publish. The time for case-based research to flourish is now!

REFERENCES

1.

Benbasat, I., Goldstein, D., and Mead, M. (1987), The case research strategy in studies of information

systems, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 11, No. 3, 369-386.

JITCAR, Volume 10, Number 1, 2008

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

The Case for Case-Based Research

Desouza, K., El Sawy, O., Galliers, R., Loebbecke, C., and Watson, R. (2006), Beyond rigor and

relevance towards responsibility and reverberation: Information systems research that really matters,

Communications of AIS, Vol. 17, No. 16,2-26.

Dubt, L. and Part!, G. (2003), Rigor in information systems positivist case research: Current practices,

trends, and recommendations, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 27, No. 4, 597-635.

Jans, R. and Dittrich, K. (2008), A review of case studies in business research, in Case Study

Methodology In Business Research, Eds: Jan Dul and Tony Hak, Oxford (England): ButterworthHeinemann.

King, J. and Lyytinen, K. (2006), The market of ideas as the center of the IS field, Communications of

AIS, Vol. 7 , NO. 38, 2-19.

Klein, H. and Hirschheim, R. (2003), Crisis in the IS field? A critical reflection on the state of the

discipline, Journal of AIS, Vol. 4, No. 10, 237-293.

Klein, H. and Myers, M. (1999), A set of principles for conducting and evaluating interpretive field

studies in information systems, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 23, No. 1, 67-97.

Palvia, S. (1999), Research based on cases and applications studies, Journal of Information

Technology Cases and Applications, Vol. 1, No. 1.

Yin, R. (2003), Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 3d Ed., Applied Social Research Methods

Series, Vol5, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Steven R. Gordon is Editor-in-Chief of JITCAR and Professor of Information Technology

Management at Babson College, Wellesley, MA. Dr. Gordon's research and consulting interests

focus on three areas: how IT affects corporate innovation, governance of information technology

services, and ecomrnerce in the financial service industry. His research appears in the

Communications of the ACM, Information & Management, Information Systems Management,

the International Journal of Service Industry Management, Journal of Strategic Information

Systems, and other academic journals. He is the editor of Computing Information Technology:

The Human Side (IRM Press) and Information Technology and E-Business in the Financial

Services (Ivy League Publishing, 2004). He is a co-author of the textbooks Information Systems:

A Management Approach (Wiley, 3rd edition) and Essentials of Accounting Information Systems

( U . of Phoenix).

JITCAR, Volume 10, Number 1, 2008

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Qualitative Research:: Intelligence for College StudentsDa EverandQualitative Research:: Intelligence for College StudentsValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1)

- Understanding and Misunderstanding Randomized Controlled Trials - PMCDocumento46 pagineUnderstanding and Misunderstanding Randomized Controlled Trials - PMCEDESSEU PASCALNessuna valutazione finora

- Correlational Research: Case StudiesDocumento2 pagineCorrelational Research: Case Studieszia shaikhNessuna valutazione finora

- To Tell or Not to Tell The Ethical Dilemma of the Would-Be WhistleblowerDocumento16 pagineTo Tell or Not to Tell The Ethical Dilemma of the Would-Be WhistleblowershaiteekayNessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter FourDocumento6 pagineChapter Fourzambezi244Nessuna valutazione finora

- Thesis Supervision in The Social SciencesDocumento7 pagineThesis Supervision in The Social Sciencesaouetoiig100% (2)

- Exploratory StudyDocumento6 pagineExploratory StudyWaseem AkramNessuna valutazione finora

- Basic (Aka Fundamental or Pure) Research Is Driven by A Scientist's Curiosity or Interest in ADocumento35 pagineBasic (Aka Fundamental or Pure) Research Is Driven by A Scientist's Curiosity or Interest in AFaiha AfsalNessuna valutazione finora

- Q1.Discuss The Various Experimental Designs As Powerful Tools To Study The Cause and Effect Relationships Amongst Variables in Research. AnsDocumento10 pagineQ1.Discuss The Various Experimental Designs As Powerful Tools To Study The Cause and Effect Relationships Amongst Variables in Research. AnsLalit ThakurNessuna valutazione finora

- Definition and PurposeDocumento6 pagineDefinition and PurposeHerrieGabicaNessuna valutazione finora

- Quantitative ResearchDocumento6 pagineQuantitative ResearchShineNessuna valutazione finora

- Study Scope and ApproachDocumento4 pagineStudy Scope and ApproachpearlsNessuna valutazione finora

- Testing Hypothesis Main PagesDocumento32 pagineTesting Hypothesis Main Pagesneha16septNessuna valutazione finora

- Evaluating_ResearchDocumento3 pagineEvaluating_ResearchCwen Jazlyn SumalinogNessuna valutazione finora

- Kinds of Research MethodsDocumento6 pagineKinds of Research Methodscindy juntongNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Write A Meta Analysis Research PaperDocumento9 pagineHow To Write A Meta Analysis Research Paperzijkchbkf100% (1)

- Experimental Practices and Objectivity in The SocialDocumento31 pagineExperimental Practices and Objectivity in The SocialDeane UmbohNessuna valutazione finora

- First Quarter LessonsDocumento6 pagineFirst Quarter LessonsshinnnnkagenouNessuna valutazione finora

- Social Science Dissertation Methodology SampleDocumento5 pagineSocial Science Dissertation Methodology SamplePaySomeoneToWriteYourPaperSpringfield100% (1)

- Qualitative Research Methods For Institutional Analysis: David SkarbekDocumento14 pagineQualitative Research Methods For Institutional Analysis: David SkarbekDreamofunityNessuna valutazione finora

- Exploring business research types like exploratory, descriptive, applied, basic, qualitative and quantitative researchDocumento4 pagineExploring business research types like exploratory, descriptive, applied, basic, qualitative and quantitative researchTarjani MehtaNessuna valutazione finora

- Three Types of ResearchDocumento3 pagineThree Types of Researchjayson_nwuNessuna valutazione finora

- 2017-Process Tracing in Social SciencesDocumento28 pagine2017-Process Tracing in Social SciencesTudor CherhatNessuna valutazione finora

- U09d1 Non-Experimental ResearchDocumento4 pagineU09d1 Non-Experimental Researcharhodes777Nessuna valutazione finora

- The Validation of Embedded Case StudiesDocumento23 pagineThe Validation of Embedded Case StudiesHoang Minh DoNessuna valutazione finora

- Educational Research STE Autumn 2020 Code: 837 Roll No: CC622965Documento10 pagineEducational Research STE Autumn 2020 Code: 837 Roll No: CC622965Muhammad SaddamNessuna valutazione finora

- Audu Hadiza U18DLNS20510 Different Methods Used by Developmental PsychologistsDocumento3 pagineAudu Hadiza U18DLNS20510 Different Methods Used by Developmental PsychologistsHadiza Adamu AuduNessuna valutazione finora

- What Is Research Design AnalysisDocumento3 pagineWhat Is Research Design AnalysisPJ DegolladoNessuna valutazione finora

- Research Methods Assignment ExplainedDocumento25 pagineResearch Methods Assignment ExplainedDeborah AbebeNessuna valutazione finora

- Quantitative Article CritiqueDocumento8 pagineQuantitative Article CritiqueGareth McKnightNessuna valutazione finora

- ThinkingDocumento16 pagineThinkingcarlosortegapNessuna valutazione finora

- Ethics in The Changing Domain of ResearchDocumento14 pagineEthics in The Changing Domain of ResearchCabdi Wali GabeyreNessuna valutazione finora

- Non Experimental ResearchDocumento16 pagineNon Experimental ResearchAnju Margaret100% (1)

- Research TypesDocumento4 pagineResearch Typesmryoma99Nessuna valutazione finora

- The "Theories" of Polygraph TestingDocumento5 pagineThe "Theories" of Polygraph TestingAssignmentLab.comNessuna valutazione finora

- Methods in Case Study Analysis by Linda T KohnDocumento9 pagineMethods in Case Study Analysis by Linda T KohnSIVVA2Nessuna valutazione finora

- Experimental DesignDocumento11 pagineExperimental Designtangent12100% (1)

- The Hallmarks of Scientific ResearchDocumento16 pagineThe Hallmarks of Scientific Researchwajeeha tahirNessuna valutazione finora

- Research Paper Topics With Two VariablesDocumento8 pagineResearch Paper Topics With Two Variablescagvznh1100% (1)

- King, Keohane and Verba, Designing Social Inquiry, Pp. 3-9, 36-46, 115-149 Notes For Comparative Politics Field Seminar, Fall, 1998Documento5 pagineKing, Keohane and Verba, Designing Social Inquiry, Pp. 3-9, 36-46, 115-149 Notes For Comparative Politics Field Seminar, Fall, 1998Nazmus Sakib NirjhorNessuna valutazione finora

- The Quality of QualitativeDocumento7 pagineThe Quality of QualitativeJose Antonio Cegarra GuerreroNessuna valutazione finora

- Quantitative Research Methods Literature ReviewDocumento5 pagineQuantitative Research Methods Literature Reviewea7y3197100% (1)

- Descriptive Research Is Also Called Statistical ResearchDocumento6 pagineDescriptive Research Is Also Called Statistical Researcharun1811Nessuna valutazione finora

- Best AnswerDocumento167 pagineBest AnswerAlex DarmawanNessuna valutazione finora

- Where Is The Hypothesis Located in A Research PaperDocumento5 pagineWhere Is The Hypothesis Located in A Research PaperafcndgbpyNessuna valutazione finora

- Master of Business Administration – MBA Semester 3 Research MethodologyDocumento35 pagineMaster of Business Administration – MBA Semester 3 Research MethodologyjunevargheseNessuna valutazione finora

- ASSIGNMENT The Quant-Qual ImpasseDocumento7 pagineASSIGNMENT The Quant-Qual ImpasseAyeta Emuobonuvie GraceNessuna valutazione finora

- MB0034 – Exploratory, descriptive and diagnostic research examplesDocumento34 pagineMB0034 – Exploratory, descriptive and diagnostic research examplesnaren_1979Nessuna valutazione finora

- Module 1 RM: Research ProblemDocumento18 pagineModule 1 RM: Research ProblemEm JayNessuna valutazione finora

- Internal and External ValidationDocumento14 pagineInternal and External ValidationXiel John BarnuevoNessuna valutazione finora

- Characteristics of Research TypesDocumento10 pagineCharacteristics of Research TypesWarda IbrahimNessuna valutazione finora

- Business Research Method The Design of ResearchDocumento18 pagineBusiness Research Method The Design of ResearchFaisal Raheem ParachaNessuna valutazione finora

- Literature Review Systematic Review DifferenceDocumento8 pagineLiterature Review Systematic Review Differenceaflskfbue100% (1)

- Practical ResearchDocumento8 paginePractical ResearchRizaNessuna valutazione finora

- RESEARCH METHODSDocumento57 pagineRESEARCH METHODSMohammed KemalNessuna valutazione finora

- Basic (Aka Fundamental or Pure) Research Is Driven by A Scientist's Curiosity or Interest in A ScientificDocumento35 pagineBasic (Aka Fundamental or Pure) Research Is Driven by A Scientist's Curiosity or Interest in A Scientificshri_k76Nessuna valutazione finora

- Psyc 101 Assignment 2Documento9 paginePsyc 101 Assignment 2lola988Nessuna valutazione finora

- Chapter 2 NotesDocumento4 pagineChapter 2 NotesCrazy FootballNessuna valutazione finora

- Case Study Research: How Political Science Underestimates It, and Places Obstacles in Its WayDocumento20 pagineCase Study Research: How Political Science Underestimates It, and Places Obstacles in Its WayKeira EstrellaNessuna valutazione finora

- SHS Quantitative Research MethodsDocumento4 pagineSHS Quantitative Research Methodsdv vargasNessuna valutazione finora

- Baldwin, Gunnar. The Role of International Standard-Setting BodiesDocumento6 pagineBaldwin, Gunnar. The Role of International Standard-Setting Bodiesammoj850Nessuna valutazione finora

- 332INECE Submission Rio Compilation DocumentDocumento3 pagine332INECE Submission Rio Compilation Documentammoj850Nessuna valutazione finora

- Rosen StandardsDocumento21 pagineRosen Standardsammoj850Nessuna valutazione finora

- Evolutionary-Theory-Of Economic ChangeDocumento452 pagineEvolutionary-Theory-Of Economic Changequantanglement100% (1)

- Lec 17Documento13 pagineLec 17kslsmsNessuna valutazione finora

- Neo Versus EvoDocumento15 pagineNeo Versus Evoammoj850Nessuna valutazione finora

- TCB Role StandardsDocumento56 pagineTCB Role StandardsPrabath De Silva100% (1)

- JR WB Industry Policy20-20RobinsonDocumento31 pagineJR WB Industry Policy20-20Robinsonammoj850Nessuna valutazione finora

- 4levels in LDCDocumento110 pagine4levels in LDCammoj850Nessuna valutazione finora

- Archive of SIDDocumento21 pagineArchive of SIDammoj850Nessuna valutazione finora

- Zurnalo Ukio Technolog Ir Ekonom Vystymas Maketas 2009 15Documento190 pagineZurnalo Ukio Technolog Ir Ekonom Vystymas Maketas 2009 15ammoj850Nessuna valutazione finora

- SalamiDocumento11 pagineSalamiammoj850Nessuna valutazione finora

- Lab ReportDocumento5 pagineLab ReportHugsNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson Plan 2018-2019 Term 1Documento205 pagineLesson Plan 2018-2019 Term 1Athlyn DurandNessuna valutazione finora

- Overview for Report Designers in 40 CharactersDocumento21 pagineOverview for Report Designers in 40 CharacterskashishNessuna valutazione finora

- Using Snapchat For OSINT - Save Videos Without OverlaysDocumento12 pagineUsing Snapchat For OSINT - Save Videos Without OverlaysVo TinhNessuna valutazione finora

- Policies and Regulations On EV Charging in India PPT KrishnaDocumento9 paginePolicies and Regulations On EV Charging in India PPT KrishnaSonal ChoudharyNessuna valutazione finora

- Mama Leone's Profitability AnalysisDocumento6 pagineMama Leone's Profitability AnalysisLuc TranNessuna valutazione finora

- Rubric - Argumentative EssayDocumento2 pagineRubric - Argumentative EssayBobNessuna valutazione finora

- The Etteilla Tarot: Majors & Minors MeaningsDocumento36 pagineThe Etteilla Tarot: Majors & Minors MeaningsRowan G100% (1)

- ASD Manual and AISC LRFD Manual For Bolt Diameters Up To 6 Inches (150Documento1 paginaASD Manual and AISC LRFD Manual For Bolt Diameters Up To 6 Inches (150rabzihNessuna valutazione finora

- Hardware Purchase and Sales System Project ProfileDocumento43 pagineHardware Purchase and Sales System Project Profilesanjaykumarguptaa100% (2)

- Digital Citizenship Initiative To Better Support The 21 Century Needs of StudentsDocumento3 pagineDigital Citizenship Initiative To Better Support The 21 Century Needs of StudentsElewanya UnoguNessuna valutazione finora

- EQ - Module - Cantilever MethodDocumento17 pagineEQ - Module - Cantilever MethodAndrea MalateNessuna valutazione finora

- Mechanical Questions & AnswersDocumento161 pagineMechanical Questions & AnswersTobaNessuna valutazione finora

- STERNOL Specification ToolDocumento15 pagineSTERNOL Specification ToolMahdyZargarNessuna valutazione finora

- Prof. Michael Murray - Some Differential Geometry ExercisesDocumento4 pagineProf. Michael Murray - Some Differential Geometry ExercisesAnonymous 9rJe2lOskxNessuna valutazione finora

- AC7114-2 Rev N Delta 1Documento34 pagineAC7114-2 Rev N Delta 1Vijay YadavNessuna valutazione finora

- EG-45-105 Material Information Sheet (Textura) V2Documento4 pagineEG-45-105 Material Information Sheet (Textura) V2GPRNessuna valutazione finora

- Ogl422 Milestone Three Team 11 Intro Training Session For Evergreen MGT Audion Recording Due 2022apr18 8 30 PM PST 11 30pm EstDocumento14 pagineOgl422 Milestone Three Team 11 Intro Training Session For Evergreen MGT Audion Recording Due 2022apr18 8 30 PM PST 11 30pm Estapi-624721629Nessuna valutazione finora

- Strain Gauge Sensor PDFDocumento12 pagineStrain Gauge Sensor PDFMario Eduardo Santos MartinsNessuna valutazione finora

- IT SyllabusDocumento3 pagineIT SyllabusNeilKumarNessuna valutazione finora

- Manju Philip CVDocumento2 pagineManju Philip CVManju PhilipNessuna valutazione finora

- Color Codes and Irregular Marking-SampleDocumento23 pagineColor Codes and Irregular Marking-Samplemahrez laabidiNessuna valutazione finora

- ArtigoPublicado ABR 14360Documento14 pagineArtigoPublicado ABR 14360Sultonmurod ZokhidovNessuna valutazione finora

- Consumer Behaviour Towards AppleDocumento47 pagineConsumer Behaviour Towards AppleAdnan Yusufzai69% (62)

- Front Cover Short Report BDA27501Documento1 paginaFront Cover Short Report BDA27501saperuddinNessuna valutazione finora

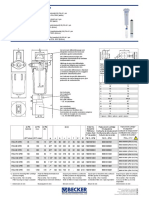

- Medical filter performance specificationsDocumento1 paginaMedical filter performance specificationsPT.Intidaya Dinamika SejatiNessuna valutazione finora

- 01 Design of Flexible Pavement Using Coir GeotextilesDocumento126 pagine01 Design of Flexible Pavement Using Coir GeotextilesSreeja Sadanandan100% (1)

- DANZIG, Richard, A Comment On The Jurisprudence of The Uniform Commercial Code, 1975 PDFDocumento17 pagineDANZIG, Richard, A Comment On The Jurisprudence of The Uniform Commercial Code, 1975 PDFandresabelrNessuna valutazione finora

- SuffrageDocumento21 pagineSuffragejecelyn mae BaluroNessuna valutazione finora

- Startups Helping - India Go GreenDocumento13 pagineStartups Helping - India Go Greensimran kNessuna valutazione finora

- Dark Data: Why What You Don’t Know MattersDa EverandDark Data: Why What You Don’t Know MattersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (3)

- Business Intelligence Strategy and Big Data Analytics: A General Management PerspectiveDa EverandBusiness Intelligence Strategy and Big Data Analytics: A General Management PerspectiveValutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (5)

- Agile Metrics in Action: How to measure and improve team performanceDa EverandAgile Metrics in Action: How to measure and improve team performanceNessuna valutazione finora

- Concise Oracle Database For People Who Has No TimeDa EverandConcise Oracle Database For People Who Has No TimeNessuna valutazione finora

- Blockchain Basics: A Non-Technical Introduction in 25 StepsDa EverandBlockchain Basics: A Non-Technical Introduction in 25 StepsValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (24)

- Monitored: Business and Surveillance in a Time of Big DataDa EverandMonitored: Business and Surveillance in a Time of Big DataValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1)

- Microsoft Access Guide to Success: From Fundamentals to Mastery in Crafting Databases, Optimizing Tasks, & Making Unparalleled Impressions [III EDITION]Da EverandMicrosoft Access Guide to Success: From Fundamentals to Mastery in Crafting Databases, Optimizing Tasks, & Making Unparalleled Impressions [III EDITION]Valutazione: 5 su 5 stelle5/5 (8)

- DB2 11 for z/OS: SQL Basic Training for Application DevelopersDa EverandDB2 11 for z/OS: SQL Basic Training for Application DevelopersValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1)

- Grokking Algorithms: An illustrated guide for programmers and other curious peopleDa EverandGrokking Algorithms: An illustrated guide for programmers and other curious peopleValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (16)

- Information Management: Strategies for Gaining a Competitive Advantage with DataDa EverandInformation Management: Strategies for Gaining a Competitive Advantage with DataNessuna valutazione finora

- Joe Celko's SQL for Smarties: Advanced SQL ProgrammingDa EverandJoe Celko's SQL for Smarties: Advanced SQL ProgrammingValutazione: 3 su 5 stelle3/5 (1)

- Data Governance: How to Design, Deploy, and Sustain an Effective Data Governance ProgramDa EverandData Governance: How to Design, Deploy, and Sustain an Effective Data Governance ProgramValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5)

- R: Recipes for Analysis, Visualization and Machine LearningDa EverandR: Recipes for Analysis, Visualization and Machine LearningNessuna valutazione finora

- SQL QuickStart Guide: The Simplified Beginner's Guide to Managing, Analyzing, and Manipulating Data With SQLDa EverandSQL QuickStart Guide: The Simplified Beginner's Guide to Managing, Analyzing, and Manipulating Data With SQLValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (46)

![Microsoft Access Guide to Success: From Fundamentals to Mastery in Crafting Databases, Optimizing Tasks, & Making Unparalleled Impressions [III EDITION]](https://imgv2-1-f.scribdassets.com/img/word_document/610686937/149x198/9ccfa6158e/1713743787?v=1)