Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

A Theory of Corporate Scandals - Why The USA and Europe Diff

Caricato da

Mathilda ChanTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

A Theory of Corporate Scandals - Why The USA and Europe Diff

Caricato da

Mathilda ChanCopyright:

Formati disponibili

OXFORD REVIEW OF ECONOMIC POLICY, VOL. 21, NO.

2

DOI: 10.1093/oxrep/gri012

JOHN C. COFFEE, JR

Columbia University Law School

A wave of financial irregularity in the USA in 20012 culminated in the SarbanesOxley Act. A worldwide stockmarket bubble burst over this same period, with the actual market decline being proportionately more severe in

Europe. Yet, no corresponding wave of financial scandals involving a similar level of companies occurred in

Europe. Given the higher level of public and private enforcement in the USA for securities fraud, this contrast seems

perplexing. This paper submits that different kinds of scandals characterize different systems of corporate governance. In particular, dispersed ownership systems of governance are prone to the forms of earnings management that

erupted in the USA, but concentrated ownership systems are much less vulnerable. Instead, the characteristic

scandal in such systems is the appropriation of private benefits of control. This paper suggests that this difference

in the likely source of, and motive for, financial misconduct has implications both for the utility of gatekeepers as

reputational intermediaries and for design of legal controls to protect public shareholders. The difficulty in

achieving auditor independence in a corporation with a controlling shareholder may also imply that minority

shareholders in concentrated ownership economies should directly select their own gatekeepers.

I. INTRODUCTION

Corporate scandals, particularly when they occur in

concentrated outbursts, raise serious issues that

scholars have too long ignored. Two issues stand

out. First, why do different types of scandals occur

in different economies? Second, why does a wave

of scandals occur in one economy, but not in another, even though both economies are closely

interconnected in the same global economy and

1

198

subject to the same macroeconomic conditions?

This brief essay seeks to relate answers to both

questions to the structure of share ownership.

Conventional wisdom explains a sudden concentration of corporate financial scandals as the consequence of a stock-market bubble. When the bubble

bursts, scandals follow, and, eventually, new regulation.1 Historically, this has been true at least since

the South Seas Bubble, and this hypothesis works

For a pre-SarbanesOxley review of the last 300 years of this pattern, see Banner (1997).

Oxford Review of Economic Policy vol. 21 no. 2 2005

The Author (2005). Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

Downloaded from http://oxrep.oxfordjournals.org at Hong Kong Polytechnic University on May 18, 2010

A THEORY OF CORPORATE

SCANDALS: WHY THE USA

AND EUROPE DIFFER

J. C. Coffee, Jr

While Europe also had financial scandals over this

same period (with the Parmalat scandal being the

most notorious4), most were characteristically different from the US style of earnings manipulation

scandal (of which Enron and WorldCom were the

iconic examples). Only European firms cross-listed

in the United States seem to have encountered

similar crises of earnings management (see section

II para. 5). What explains this difference and the

difference in frequency? This essay advances a

simple, almost self-evident thesis: differences in the

structure of share ownership account for differences in corporate scandals, both in terms of the

nature of the fraud, the identity of the perpetrators,

and the seeming disparity in the number of scandals

at any given time. In dispersed ownership systems,

corporate managers tend to be the rogues of the

story, while in concentrated ownership systems, it is

controlling shareholders who play the corresponding role. Although this point may seem obvious, its

corollary is less so: the modus operandi of fraud is

also characteristically different. Corporate managers tend to engage in earnings manipulation, while

controlling shareholders tend to exploit the private

benefits of control. Finally, and most importantly,

given these differences, the role of gatekeepers in

these two systems must necessarily also be different.5 While gatekeepers failed both at Enron and

Parmalat, they failed in characteristically different

ways. In turn, different reforms may be justified,

and the panoply of reforms adopted in the United

States, culminating in the SarbanesOxley Act of

2002, may not be the appropriate remedy in Europe.

Section II reviews the recent American scandals to

identify common denominators and the underlying

motivation that caused the sudden eruption of financial statement restatements. Section III turns to the

evidence on private benefits of control in concentrated ownership systems. Patterns also emerge

here in terms of the maturity of the capital market.

Section IV advances some tentative conclusions

about the differences in monitoring structures that

are appropriate under different ownership regimes.

At the outset, however, it should be underscored

that companies with dispersed ownership and companies with concentrated ownership co-exist in all

major jurisdictions.6 Thus, we are talking about

2

See Holmstrom and Kaplan (2003), who show that from 2001 through 31 December 2002, the US stock-market returns were

32 per cent, while France was 45 per cent, and Germany 53 per cent.

3

Although they have been rare in the past, FitchRatings, the credit ratings agency, predicts that they will become common in

Europe in 2005, as thousands of European companies switch from local accounting standards to International Financial Reporting

Standards, which are more demanding. See FitchRatings (2005).

4

For a detailed review of the Parmalat scandal, see Melis (2004).

5

The term gatekeeper will not be elaborately defined for the purposes of this short essay, but means a reputational intermediary

who pledges its considerable reputational capital to give credibility to its statements or forecasts. Auditors, securities analysts,

and credit ratings agencies are the most obvious examples. See Coffee (2004a).

6

This has been demonstrated at length. See La Porta et al. (1999).

199

Downloaded from http://oxrep.oxfordjournals.org at Hong Kong Polytechnic University on May 18, 2010

reasonably well to explain the turn-of-the-millennium experience in the USA and Europe. Worldwide, a stock-market bubble did burst in 2000, and

in percentage terms the decline was greater in many

European countries than in the United States.2 But

in Europe, this sudden market decline was not

associated with the same pervasive accounting and

financial irregularity that shook the US economy

and produced the SarbanesOxley Act in 2002.

Indeed, financial statement restatements are rare in

Europe.3 In contrast, the USA witnessed an accelerating crescendo of financial statement restatements that began in the late 1990s. The United

States General Accounting Office (GAO) has found

that over 10 per cent of all listed companies in the

United States announced at least one financial

statement restatement between 1997 and 2002

(GAO, 2002, p. 4). Later studies have placed the

number even higher (Huron Consulting Group

(2003a) discussed at the beginning of section II).

Because a financial statement restatement is a

serious event in the United States that, depending on

its magnitude, often results in a private class action,

a Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) enforcement proceeding, a major stock price drop,

and/or a management shake-up, one suspects that

these announced restatements were but the tip of

the proverbial iceberg, with many more companies

negotiating changes in their accounting practices

with their outside auditors that averted a formal

restatement.

OXFORD REVIEW OF ECONOMIC POLICY, VOL. 21, NO. 2

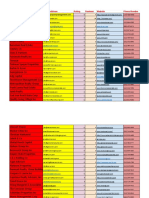

Figure 1

Total number of Restatement Announcements Identified, 19972002

300

250

(projected

for year end)

250

200

50

174

92

102

1997

1998

201

225

125

(actual)

100

0

1999

tendencies and not any iron law that admits of no

exception. As much scholarship has demonstrated,

the corporate universe divides, more or less, into two

basically alternative systems of corporate governance:

(i) a dispersed ownership system, characterized

by strong securities markets, rigorous disclosure standards, high share turnover, and high

market transparency, in which the market for

corporate constitutes the ultimate disciplinary

mechanism; and

(ii) a concentrated ownership system, characterized by controlling blockholders, weaker securities markets, high private benefits of control, and lower disclosure and market transparency standards, but with a possibly

substitutionary role played by large banks and

non-controlling blockholders.7

This essay advances only the idea that the role of

gatekeepers also differs across these legal regimes

and that gatekeepers, including even the auditor,

arguably play a more central and critical role in the

dispersed ownership system.

2000

2001

2002 (as of

30 June)

II. FRAUD IN DISPERSED

OWNERSHIP SYSTEMS

While studies differ, all show a rapid acceleration in

financial statement restatements in the United States

during the 1990s. The earliest of these studies finds

that the number of earnings restatements by publicly

held US corporations averaged roughly 49 per year

from 1990 to 1997, increased to 91 in 1998, and then

soared to 150 and 156 in 1999 and 2000, respectively

(see Moriarty and Livingston, 2001, pp. 534). A

later study by the United States GAO shows an

even more dramatic acceleration, as set forth in

Figure 1 (GAO, 2002).

Even this study understated the severity of this

sudden spike in accounting irregularity. Because

companies do not uniformly report a restatement in

the same fashion, the GAO was not able to catch all

restatements in its study. A more recent, fuller study

in 2003 by Huron Consulting Group8 shows the

following results: in 1990, there were 33 earnings

restatements; in 1995, there were 50 (Huron Consulting Group, 2003a); then, the rate truly accelerated to 216 in 1999; to 233 in 2000; to 270 in 2001;

and then in 2002, the number peaked at 330 (ten

For an overview of these rival systems, see Coffee (2001).

See Huron Consulting Group (2003b, p. 4). The number of restatements fell (slightly) to 323 in 2003 (Huron Consulting Group,

2003b). Not all these restatements involved overstatements of earnings (and some involved understatements). Still, the rising rate

of restatements seems a good proxy for financial irregularity.

7

8

200

Downloaded from http://oxrep.oxfordjournals.org at Hong Kong Polytechnic University on May 18, 2010

150

J. C. Coffee, Jr

times the 1990 level). On this basis, roughly one in

eight listed companies restated over this period. An

update this year by Huron Consulting shows that the

number of restatements fell to 323 in 2003 and then

rose again to 414 in 2004.9 In any event, even if the

exact number of restatements is disputed, the

overall pattern of a hyperbolic rate of increase

around the turn of the millennium persists across

all studies.

Other studies have reached similar results. Studying

a comprehensive sample of firms that restated

annual earnings from 1971 to 2000, Richardson et

al. (2002, p. 4) reported a negative market reaction

to the announcement of the restatement of 11 per

cent over a 3-day window surrounding the announcement. Moreover, using a wider window that

measured firm value over a period from 120 days

prior to the announcement to 120 days after it, they

found that restating firms lose on average 25 per

cent of market value over the period examined and

this is concentrated in a narrow window surrounding

the announcement of the restatement (Richardson

et al., 2002, p. 16). Twenty-five per cent of market

value represents an extraordinary market penalty. It

shows the market not simply to have been surprised,

but to have taken the restatement as a signal of

fraud. For example, in the cases of Cendant,

MicroStrategy, and Sunbeam, three major US corporate scandals in the late 1990s, they found that

these three firms lost more than $23 billion in the

week surrounding their respective restatement announcements (Richardson et al., 2002).

The intensity of the markets negative reaction to an

earnings restatement varied with the cause of the

The prevalence of revenue recognition problems,

even in the face of the markets sensitivity to them,

shows a significant change in managerial behaviour

in the United States. During earlier periods, US

managements famously employed rainy day reserves to hold back the recognition of income that

was in excess of the markets expectation in order

to defer its recognition until some later quarter when

there had been a shortfall in expected earnings. In

effect, managers engaged in income-smoothing,

rolling the peaks in one period over into the valley of

the next period. This traditional form of earnings

management was intended to mask the volatility of

earnings and reassure investors who might have

been alarmed by rapid fluctuations in earnings. In

contrast, managers in the late 1990s appear to have

characteristically stolen earnings from future periods in order to create an earnings spike that

potentially could not be sustained. Why? Although it

had long been known that restating firms were

typically firms with high market expectations for

future growth, the pressure on these firms to show

a high rate of earnings growth appears to have

increased during the 1990s.

9

See Huron Consulting Group (2005). If one wishes to focus only on restatements of the annual audited financial statements,

excluding restatements of quarterly earnings, the numbers were: 2000, 98; 2001, 140; 2002, 183; 2003, 206; 2004, 253.

10

Anderson and Yohn (2002, p. 13). This loss was measured in terms of cumulative abnormal returns (CAR). Where the cause

of the restatement was reported as fraud, the CAR rose to 19 per cent, but there were only a handful of such cases.

201

Downloaded from http://oxrep.oxfordjournals.org at Hong Kong Polytechnic University on May 18, 2010

Nor were these restatements merely technical adjustments. Although some actually increased earnings, the GAO study found that the typical restating

firm lost an average 10 per cent of its market

capitalization over a 3-day trading period surrounding the date of the announcement (GAO, 2002, p. 5).

All told, the GAO estimated the total market losses

(unadjusted for other market movements) at $100

billion for restating firms in its incomplete sample for

19972002 (GAO, 2002, p. 34).

restatement, with the most negative reactions being

associated with restatements involving revenue recognition issues (see Anderson and Yohn, 2002).

One study, examining just the period from 1997 to

1999, found that firms in which revenue recognition

issues caused the restatement experienced a well

above average, market-adjusted loss of 13.38 per

cent over a window period beginning 3 days before

the announcement and continuing until 3 days after

it.10 Revenue recognition errors essentially revealed

management not just to have been mistaken, but to

have cheated, and the market reacted accordingly.

Yet, despite the markets fear of such practices,

revenue recognition errors became the dominant

cause of restatements in the period from 1997 to

2002. The GAO Report found that revenue recognition issues accounted for almost 38 per cent of the

restatements it identified over that period (GAO,

2002, p. 28), and the Huron Consulting Group study

also found it to be the leading accounting issue

underlying an earnings restatement between 1999

and 2003 (Huron Consulting Group, 2003a, p. 4).

OXFORD REVIEW OF ECONOMIC POLICY, VOL. 21, NO. 2

Figure 2

CEO Compensation at S&P 500 Industrial Companies, 19802001

Cash

66%

8

Equity

63%

60%

58%

54%

32%

43%

40%

37%

49%

1

0

1980

1983

1986

1989

1992

1995

1998

2001

Source: Brian J. Hall, Harvard Business School.

What, in turn, caused this increased pressure? To a

considerable extent, it appears to have been selfinducedthat is, the product of increasingly optimistic predictions by managements to financial analysts as to future earnings. But this answer just

translates the prior question into a different format:

why did managements become more optimistic

about earnings growth over this period? Here, one

explanation does distinguish the USA from Europe,

and it has increasingly been viewed as the best

explanation for the sudden spike in financial irregularity in the USA.11 Put simply, executive compensation abruptly shifted in the United States during

the 1990s, moving from a cash-based system to an

equity-based system. More importantly, this shift

was not accompanied by any compensating change

in corporate governance to control the predictably

perverse incentives that reliance on stock options

can create.

One measure of the suddenness of this shift is the

change over the decade in the median compensation

of a chief executive officer (CEO) of an S&P 500

industrial company. As of 1990, the median such

CEO made $1.25m with 92 per cent of that amount

paid in cash and 8 per cent in equity (see Hall, 2003).

But during the 1990s, both the scale and composition

of executive compensation changed. By 2001, the

202

To illustrate the impact of this change, assume a

CEO holds options on 2m shares of his companys

stock and that the company is trading at a price to

earnings ratio of 30 to 1 (both reasonable assumptions for this era). On this basis, if the CEO can

cause the premature recognition of revenues that

result in an increase in annual earnings by simply $1

per share, the CEO has caused a $30 price increase

that should make him $60m richer. Not a small

incentive!

Obviously, when one pays the CEO with stock

options, one creates incentives for short-term financial manipulation and accounting gamesmanship.

Financial economists have found a strong statistical

correlation between higher levels of equity compensation and both earnings management and financial

restatements. One recent study by Efendi et al.

(2004) utilized a control group methodology and

constructed two groups of companies, each composed of 100 listed public companies.12 The first

groups members had restated their financial statements in 2001 or 2002, while the control group was

For a fuller account of these various explanations, see Coffee (2004b).

Efendi et al. (2004). For an earlier similar study, see Johnson et al. (2003).

11

12

median CEO of an S&P industrial company was

earning over $6m, of which 66 per cent was in equity

(Hall, 2003). Figure 2 shows the swiftness of this

transition (Hall, 2003).

Downloaded from http://oxrep.oxfordjournals.org at Hong Kong Polytechnic University on May 18, 2010

Median CEO pay ($m)

J. C. Coffee, Jr

Other studies have reached similar results. Denis et

al. (2005) find a significant positive relationship

between a firms use of option-based compensation

and securities fraud allegations being levelled against

the firm.13 Further, they find in their study of 358

companies charged with fraud between 1993 and

2002 that the likelihood of a fraud charge is positively related to option intensityi.e. the greater

the amount of the options, the higher the likelihood

(Denis et al., 2005, p. 4). Similarly, Cheng and

Warfield (2004) have documented that corporate

managers with high equity incentives sell more

shares in subsequent periods, are more likely to

report earnings that just meet or exceed analysts

forecasts, and more frequently engage in other

forms of earnings management. As stock options

increase the managers equity ownership, they also

increase their need to diversify the high risk associated with such ownership, and this produces both

more efforts to inflate earnings to prevent a stock

price decline and increased sales by managers in

advance of any earnings decline. In short, there is a

dark side to option-based compensation for senior

executives: absent special controls, more options

mean more fraud.

At this point, the contrast between managerial

incentives in the USA and Europe comes into

clearer focus. These differences involve both the

scale of compensation and its composition. In 2004,

CEO compensation as a multiple of average employee compensation was estimated to be 531:1 in

the USA, but only 16:1 in France, 11:1 in Germany,

10:1 in Japan, and 21:1 in nearby Canada. Even

Great Britain, with the system of corporate governance most closely similar to that of the USA, had

only a 25:1 ratio (see Morgenson, 2004). But even

more important is the shift towards compensating

the chief executive primarily with stock options.

While stock options have come to be widely used in

recent years in Europe, equity compensation constitutes a much lower percentage of total CEO compensation (even in the UK, it was only 24 per cent

in 2002) (see Ferrarini et al., 2003, p. 7, fn. 21).

European CEOs not only make much less, but their

total compensation is also much less performance

related.14

What explains these differences? Compensation

experts in the USA usually emphasize the tax laws

in the United States, which were amended in the

early 1990s to restrict the corporate deductibility of

high cash compensation and thus induced corporations to use equity in preference to cash.15 But this

is only part of the fuller story. Much of the explanation is that institutional investors in the USA pressured companies for a shift towards equity compensation. Why? Institutional investors, who hold the

majority of the stock in publicly held companies in

the USA, understand that, in a system of dispersed

ownership, executive compensation is probably their

most important tool by which to align managerial

incentives with shareholder incentives. Throughout

the 1960s and 1970s, they had seen senior managements of large corporations manage their firms in a

risk-averse and growth-maximizing fashion, retaining free cash flow to the maximum extent possible.

Such a style of management produced the bloated,

and inefficient conglomerates of that era (for example, Gulf & Western and IT&T). Put simply, a

system of exclusively cash compensation creates

incentives to avoid risk and bankruptcy and to

maximize the size of the firm, regardless of profit-

13

See Denis et al. (2005). For an earlier study finding that the greater use of option-related compensation results in greater private

securities litigation, see Peng and Roell (2004).

14

Ferrarini et al. (2003, pp. 67) note that performance-related pay is in wide use only in the UK, and that controlling shareholders

tend to resist significant use of incentive compensation.

15

In 1993, Congress enacted Section 162(m) of the Internal Revenue Code, which denies a tax deduction for annual compensation

in excess of $1m per year paid to the CEO, or the next four most highly paid officers, unless special tests are satisfied. Its passage

forced a shift in the direction of equity compensation. For a fuller account of this change, see Coffee (2004b, pp. 2745).

203

Downloaded from http://oxrep.oxfordjournals.org at Hong Kong Polytechnic University on May 18, 2010

composed of otherwise similar firms that had not

restated. What characteristic most distinguished the

two groups? The leading factor that proved most to

influence the likelihood of a restatement was the

presence of a substantial amount of in the money

stock options in the hands of the firms CEO. The

CEOs of the firms in the restating group held on

average in the money options of $30.9m, while

CEOs in the non-restating control group averaged

only $2.3ma nearly 14 to 1 difference (Efendi et

al., 2004, p. 2). Further, if a CEO held options

equalling or exceeding 20 times his or her annual

salary (and this was the 80th percentile in their

studymeaning that a substantial number of CEOs

did exceed this level), the likelihood of a restatement

increased by 55 per cent.

OXFORD REVIEW OF ECONOMIC POLICY, VOL. 21, NO. 2

ability, because a larger firm size generally implies

higher cash compensation for its senior managers.

One measure of this transition is the changing nature

of financial irregularities. The SarbanesOxley Act

required the SEC to study all its enforcement proceedings over the prior 5 years (i.e. 19972002) to

ascertain what kinds of financial and accounting

irregularities were the most common. Out of the 227

enforcement matters pursued by the SEC over

this period, the SEC has reported that 126 (or 55 per

cent) alleged improper revenue recognition (SEC,

2003, p. 2). Similarly, the earlier noted GAO Study

found that 38 per cent of all restatements in its

survey were for revenue recognition timing errors.

Either managers were recognizing the next periods

revenues prematurelyor they were simply inventing revenues that did not exist. Both forms of errors

suggest that managers were striving to manufacture

an artificial (and possibly unsustainable) spike in

corporate income.

That managers were systematically able to overestimate revenues and then recognize them prematurely in ways that ultimately compelled earnings

restatements shows a market failureparticularly

when the market penalty for premature revenue

recognition was, as earlier noted, so Draconian as to

result in a 25 per cent decline in market price on

average (see section II, para. 4). Why did securities

analysts accept such optimistic predictions and not

discount them? Here, the evidence is that very few

III. FRAUD IN CONCENTRATED

OWNERSHIP REGIMES

The pattern in concentrated ownership systems is

very different, but not necessarily better. In the case

of most European corporations, there is a controlling

shareholder or shareholder group.18 Why is this

important? A controlling shareholder does not need

to rely on indirect mechanisms of control, such as

equity compensation or stock options, in order to

incentivize management. Rather, it can rely on a

command and control system because, unlike the

dispersed shareholders in the USA, it can directly

monitor and replace management. Hence, corporate managers have both less discretion to engage in

opportunistic earnings management and less motivation to create an earnings spike (because it will not

benefit a management not compensated with stock

options).

Equally important, the controlling shareholder also

has much less interest in the day-to-day stock price

of its company. Why? Because the controlling

shareholder seldom, if ever, sells its control block

into the public market. Rather, if it sells at all, it will

See Griffin (2002), who reports a study of 847 companies sued in federal securities class actions between 1994 and 2001.

Desai et al. (2004). For a similar study, see Efendi et al. (2005).

18

For excellent overviews of European ownership patterns, see Franks and Mayer (1997), La Porta et al. (1999), and Barca and

Becht (2001).

16

17

204

Downloaded from http://oxrep.oxfordjournals.org at Hong Kong Polytechnic University on May 18, 2010

Once the US tax laws and institutional pressure

together produced a shift to equity compensation in

the 1990s, managers incentives changed, and managers sought to maximize share value (as the institutions had wanted). But what the institutions failed

to anticipate was that there can be too much of a

good thing. Aggressive use of these incentives in

turn encouraged the use of manipulative techniques

to maximize stock price over the short run. Although

such spikes may not be sustainable, corporate managers possess asymmetric information, and anticipating their inability to maintain earnings growth,

they can exercise their options and bail out.

analysts downgraded public companies in the months

prior to earnings restatementseven though short

sellers and insiders had recognized the likelihood of

an earnings restatement.16 Yet, while analysts and

auditors may have been slow to recognize premature revenue recognition, considerable evidence

suggests that short sellers were able to recognize

the signals and profit handsomely by anticipating

earnings restatements.17 The implications of this

point are that smart traders could and did do what

professional gatekeepers were insufficiently motivated to do: recognize the approach of major market

collapses. In short, this is a story of gatekeeper

failure in that the professional agents of corporate

governance did not adequately serve investors. In

consequence, the SarbanesOxley Act of 2002

understandably focused on gatekeepers and mandated closer scrutiny of auditors, securities analysts,

and credit-rating agencies.

J. C. Coffee, Jr

This generalization may seem subject to counterexamples. For example, some well-known European companiese.g. Vivendi Universal, Royal

Ahold, Skandia Insurance, or Adecco20did experience accounting irregularities. But these are exceptions that prove the rule. Nearly all were US

listed companies whose accounting problems emanated from US-based subsidiaries, and several had

transformed themselves into American-style conglomerates (the leading example being Vivendi) that

either awarded stock options or needed to maximize

their short-term stock price in order to make multiple

acquisitions.

Potentially, some of this disparity between Europe

and the United States could be an artefact of less

rigorous regulatory oversight of public companies in

Europe or, alternatively, of the lesser litigation risk in

Europe. Hence, European issuers might be less

willing to restate their financial statements, even

when they discover a past error, because they do not

expect regulatory authorities or the plaintiffs bar to

hold them accountable. While this point has some

validity, it should not be overextended. The less

demanding scrutiny given the financial statements

of public issuers in Europe (particularly in the secondary-market context, where securities are not

being issued) still does not supply a motor force or

an incentive for financial manipulation. Even if

European issuers could inflate their financial statements, they had less reason to do so. Finally, financial-statement inflation can lead to the ultimate

collapse of the corporate issuer when the market

eventually discovers the fraud (as Enron and

WorldCom illustrate). Here, European examples of

similar collapses are conspicuously absent.21

Does this analysis imply that European managers

are more ethical, or that European shareholders are

better off than their American counterparts? By no

means! Concentrated ownership encourages a different type of financial overreaching: the extraction

of private benefits of control. Dyck and Zingales

(2004) have shown that the private benefits of

control vary significantly across jurisdictions, ranging from 4 per cent to +65 per cent, depending in

significant part on the legal protections given minority shareholders.22 While there is evidence that the

market cares about the level of private benefits that

controlling shareholders will extract (see Ehrhardt

and Nowack, 2003), the market has a relatively

weak capacity to discern on a real-time basis what

benefits are in fact being expropriated.

In emerging markets, the expropriation of private

benefits typically occurs through financial transactions. Ownership may be diluted through public

offerings, and then a coercive tender offer or

19

See Dyck and Zingales (2004), discussed below; see also Nenova (2000), who finds significantly higher control premiums in

countries relying on French civil law and high, but lower, premiums in countries using German civil law; these control premiums

were significantly above the average premiums in common law countries; Zingales (1995).

20

Both the financial scandals at Adecco and Royal Ahold originated in the United States and, at least initially, centred around

accounting at US subsidiaries. See Simonian (2004); McCoy (2005) notes that Royal Aholds accounting problems began at US

Foodservices, Inc., a subsidiary of Royal Ahold, where the US managers were compensated with stock options; Vivendi Universal

can be described as a US-style acquisitions-oriented financial conglomerate. See Johnson (2004).

21

If one goes back far enough, one can certainly find examples of sudden financial collapse in Europefor example,

Metallgesellschaft in 1994. See Fisher (1995). But more recent examples are largely lacking. Also, Metallgesellschafts financial

distress seems more to have been the product of the negligent mishandling of derivatives than any fraudulent desire to inflate earnings.

See also Edwards and Canter (1995). Such accounting scandals as have occurred in Germanyfor example, the fraud at KlocknerHumboldt-Deuta or the collapse of the Jurgen Schneider real estate empireinvolved longstanding frauds in which assets were

overstated and liabilities understated with the apparent acquiescence of both auditors and, sometimes, the principal lending bank.

The monitoring failures in these cases much more closely resemble Parmalat than Enron. Many of these failures are reviewed in

Wenger and Kaserer (1998).

22

See Dyck and Zingales (2004); see also Nenova (2000).

205

Downloaded from http://oxrep.oxfordjournals.org at Hong Kong Polytechnic University on May 18, 2010

make a privately negotiated sale at a substantial

premium over the market price to an incoming, new

controlling shareholder. Such control premiums are

characteristically much higher in Europe than in the

United States.19 As a result, controlling shareholders in Europe do not obsess over the day-to-day

market price and rationally do not engage in tactics

to recognize revenues prematurely to spike their

stock price. These two explanationsless use of

equity compensation and less interest in the shortterm stock priceexplain, at least in part, why there

were fewer accounting irregularities in Europe than

in the USA during the late 1990s.

OXFORD REVIEW OF ECONOMIC POLICY, VOL. 21, NO. 2

In more developed economies, such financial transactions may be precluded. Instead, operational

mechanisms can be used: for example, controlling

shareholders can compel the company to sell its

output to, or buy its raw materials from, a corporation that they independently own. In emerging markets, growing evidence suggests that firms within

corporate groups engage in more related party

transactions than firms that are not members of a

controlled group (see Ming and Wong, 2003). In

essence, these transactions permit controlling shareholders to transfer resources from companies in

which they have lesser cash-flow rights to ones in

which they have greater cash-flow rights (see

Bertrand et al., 2000).

Although it may be tempting to deem tunnelling and

related opportunistic practices as characteristic only

of emerging markets where legal protections are

still evolving, considerable evidence suggests that

such practices are also prevalent in more mature

European economies.25 Indeed, some students of

European corporate governance claim that the dominant form of concentrated ownership (i.e. absolute

majority ownership) is simply inefficient because it

permits too much predatory misbehaviour (see

Kirchmaier and Grant, 2004b).

A danger lurks here in seeking to prove too much.

If European corporate governance were as vulnerable to opportunistic behaviour by controlling shareholders as some critics suggest, then one wonders

why minority shareholders would invest at all and

why even thin securities markets could survive.

Perhaps, the answer is that other actors substitute

for the role that gatekeepers play in dispersed

ownership legal regimes. For example, some argue

that the universal banks, which typically hold large,

but non-controlling blocks of stock as well as advancing debt capital, play such a protective role.26

Others point to the impact of co-determination,

which gives labour a major voice in corporate

governance in some European countries that it lacks

in Anglo-Saxon legal systems.27 Still others point to

cross-monitoring by other blockholders.28 All these

answers encounter problems, which need not be

resolved in this essay. All that need be asserted here

is that there is less reason to believe that gatekeepersthat is, professional agents serving shareholders but selected by the corporationwork as well in

concentrated ownership regimes as in dispersed

ownership regimes.

To understand this contention, it is useful to examine

the nature of the scandals that characterize concentrated ownership systems because they seem to

show a distinct and different type of gatekeeper

failure. Two recent scandals typify this pattern:

Parmalat and Hollinger. Parmalat is the paradigmatic fraud for Europe (just as Enron and WorldCom

are the representative frauds in the United States).

Parmalats fraud essentially involved the balance

sheet, not the income statement. It failed when a

3.9 billion account with Bank of America proved to

be fictitious.29 At least, $17.4 billion in assets mysteriously vanished from its balance sheet. Efforts by

its trustee to track down these missing funds appear

For the article coining this term, see Johnson et al. (2000).

See Atanasov et al. (2005). These authors estimate that these transactions occurred at about 25 per cent of the shares intrinsic value.

25

Many commentators have criticized German corporate governance on the grounds that it permits controlling shareholders to

diverge from a pro rata distribution of enterprise cash flows, for example, through one-sided transfer pricing arrangements with

affiliated companies, or asset sales on favourable terms to affiliates. See Gordon (1999). If this is the problem, an independent auditor

is probably not the answer, as it cannot stop such transactions. For a more recent overview of the means by which controlling

shareholders currently divert value to themselves in Europe, see Kirchmaier and Grant (2004a).

26

This was once the consensus view. But more recently, sceptics have demonstrated that the universal banks in Germany have

few representatives on the supervisory board, tend to do no more monitoring than banks in dispersed ownership regimes, and largely

defer to the managing boards decisions. See Edwards and Fischer (1994).

27

The impact of co-determination on corporate governance has been much debated. See, for example, Roe (1998).

28

See Gorton and Schmid (1996), who suggest the role of non-bank blockholders in monitoring the controlling shareholder.

29

This summary of the Parmalat scandal relies upon the Wall Street Journals account. See Galloni and Reilly (2004).

23

24

206

Downloaded from http://oxrep.oxfordjournals.org at Hong Kong Polytechnic University on May 18, 2010

squeeze-out merger is used to force minority shareholders to tender at a price below fair market value.

These techniques have been discussed in detail

elsewhere and in their crudest forms have been

given the epithet tunnelling to describe them.23 A

classic example was the Bulgarian experience between 1999 and 2002, when roughly two-thirds of

the 1,040 firms on the Bulgarian stock exchange

were delisted, following freeze-out tender offers for

the minority shares at below market, but still coercive, prices.24

J. C. Coffee, Jr

to have found that at least 2.3 billion were paid to

affiliated persons and shareholders.30 In short, private benefits appear to have siphoned off to controlling shareholders through related party transactions.

Unlike the short-term stock manipulations that occur in the USA, this was a scandal that had continued for many years, probably for over a decade.

The recent Hollinger scandal also involved overreaching by controlling shareholders. Although

Hollinger International is a Delaware corporation,

its controlling shareholders were Canadian, as were

most of its shareholders. According to the report

prepared by counsel to its independent directors,

former SEC Chairman Richard Breeden, Hollinger

was a kleptocracy (see Hollinger, 2004, p. 4). Its

controlling shareholders allegedly siphoned off more

than $400m from Hollingeror more than 95 per

cent of the companys adjusted net income from

1997 to 2003 (Leonard, 2004). On sales of assets by

Hollinger, its controlling shareholders secretly took

large side payments, which they directed be paid to

themselves out of the sales proceeds (Leonard,

2004). But bad as the Hollinger case may be, little

evidence suggests that Lord Black and his cronies

manipulated earnings through premature revenue

recognition. What this contrast shows is that controlling shareholders may misappropriate assets, but

have much less reason to fabricate earnings. This

does not mean that business ethics are better (or

IV. GATEKEEPER FAILURE ACROSS

OWNERSHIP REGIMES

Both ownership regimesdispersed and concentratedshow evidence of gatekeeper failure. The

USA/UK system of dispersed ownership is vulnerable to gatekeepers not detecting inflated earnings,

and concentrated ownership systems fail to the

extent that gatekeepers miss (or at least fail to

report) the expropriation of private benefits. A key

difference, of course, is that in dispersed ownership

systems the villains are managers and the victims

are shareholders, while, in concentrated ownership

systems, the controlling shareholders overreach

minority shareholders.

In turn, this raises the critical issue: can gatekeepers

in concentrated ownership systems monitor the

controlling shareholder who hires (and potentially

can fire) them? Although there clearly have been

numerous failures by gatekeepers in dispersed ownership systems, the answer for these systems probably lies in principle in redesigning the governance

circuitry within the public corporation so that the

gatekeeper does not report to those that it is expected to monitor. Thus, the auditor or attorney can be

required to report to an independent audit committee

rather than corporate managers (as SarbanesOxley

mandates). But this same answer does not work as

well in a concentrated ownership system. In such a

system, even an independent audit committee may

serve at the pleasure of a controlling shareholder.

Indeed, some forms of gatekeepers common in

dispersed ownership systems seem inherently less

likely to be effective in a system of concentrated

ownership. For example, the securities analyst is

inherently a gatekeeper for dispersed ownership

30

Galloni and Reilly (2004). Parmalats former CEO, Mr Tanzi, appears to have acknowledged to Italian prosecutors that

Parmalat funneled about Euro 500 Million to companies controlled by the Tanzi family, especially to Parmatour. See Melis (2004,

p. 6). Prosecutors appear to believe that the total diversions to Tanzi family-owned companies were at least 1,500m. Galloni

and Reilly (2004, p. 6, n. 2).

207

Downloaded from http://oxrep.oxfordjournals.org at Hong Kong Polytechnic University on May 18, 2010

At the heart of the Parmalat fraud lies a crucial

failure by its gatekeepers. Parmalats auditors for

many years had been an American-based firm,

Grant Thornton, whose personnel had audited

Parmalat and its subsidiaries since the 1980s (Galloni

and Reilly, 2004, p. 10). Although Italian law uniquely

mandated the rotation of audit firms, Grant Thornton

found an easy evasion. It gave up the role of being

auditor to the parent company in the Parmalat

family, but continued to audit its subsidiaries (Galloni

and Reilly, 2004, pp. 910). Among these subsidiaries was the Cayman-Islands-based subsidiary, Boulat

Financing Corporation, whose books showed the

fictitious Bank of America account, the discovery of

which triggered Parmalats insolvency (Galloni and

Reilly, 2004, p. 10).

worse) within a concentrated ownership regime, but

only that the modus operandi for fraud is different.

The real conclusion is that different systems of

ownership encourage characteristically different

styles of fraud. The next question becomes whether

gatekeepers can play a functionally equivalent protective role in both legal regimes.

OXFORD REVIEW OF ECONOMIC POLICY, VOL. 21, NO. 2

Even the role of the auditor differs in a concentrated

ownership system. The existence of a controlling

shareholder necessarily affects auditor independence. In a dispersed ownership system, corporate

managers might sometimes capture the audit partner of their auditor (as seemingly happened at

Enron). But the policy answer was obvious (and

SarbanesOxley quickly adopted it): rewire the

internal circuitry so that the auditor reported to an

independent audit committee. However, in a concentrated ownership system, this answer works less

well because the auditor is still reporting to a board

that is, itself, potentially subservient to the controlling shareholder. Thus, the auditor in this system is

a monitor who cannot effectively escape the control

of the party that it is expected to monitor. Although

diligent auditors could have presumably detected

the fraud at Parmalat (at least to the extent of

detecting the fictitious bank account at the Cayman

Islands subsidiary), one suspects that they would

have likely been dismissed at the point at which they

began to monitor earnestly. More generally, auditors can do little to stop squeeze-out mergers,

coercive tender offers, or even unfair related-party

transactions. These require statutory protections if

the minoritys rights are to be protected. In fairness,

shareholders in a concentrated ownership system

may receive some protection from other gatekeepers, including the large banks that typically monitor

the corporation.

There is an important historical dimension to this

point. The independent auditor arose in Britain in the

middle of the nineteenth century, just as industrialization and the growth of railroads was compelling

corporations to market their shares to a broader

audience of investors (see Littleton, 1988). Amendments in 1844 and 1845 to the British Companies

Act required an annual statutory audit with the

auditor being selected by the shareholders.31 This

made sense, because the auditor was thus placed in

a true principalagent relationship with the shareholders who relied on it. But this same relationship

does not exist when the auditor reports to shareholders in a system in which there is a controlling

shareholder. Finally, even if the auditor is asked to

report on the fairness of inter-corporate dealings or

related party transactions, this is not its core competence. Other protectionssuch as supermajority votes,

mandatory bid requirements, or prophylactic rules

may be far more valuable in protecting minority

shareholders when there is a controlling shareholder. This may explain the slower development of

auditing procedures and internal controls in Europe.

Potentially, there is a further implication for the use

of gatekeepers in concentrated ownership economies. If the controlling shareholder can potentially

dominate the selection of the auditor or other gatekeepers, then it becomes at least arguable that if the

auditor is to serve as an effective reputational

intermediary, it should be selected by the minority

shareholders and report to them. This article does

not attempt to design such an unprecedented system, but smugly contents itself with pointing out the

likely inadequacy of alternative systems. The second-best alternative would appear to be according

the auditors selection, retention, and compensation

to the independent directors.

V. CONCLUSION

This articles generalizations are not presented as

iron laws. Private benefits of control can be

misappropriated in a US public company, and recent

illustrations include the Adelphia scandal, where a

controlling family diverted assets of over $3 billion to

itself in much the same way as did the controlling

The 1844 amendment was to the Joint Stock Companies Act (see 7 & 8 Vict., Ch. 110) (1844), and the 1845 amendment was

to the Companies Clauses Consolidation Act (see 8 & 9 Vict., Ch. 16) (1845). For a more detailed review of this legislation, see

OConner (2004).

31

208

Downloaded from http://oxrep.oxfordjournals.org at Hong Kong Polytechnic University on May 18, 2010

regimes. In concentrated ownership regimes, the

volume of stock trading in its thinner capital markets

is likely to be insufficient to generate brokerage

commissions sufficient to support a profession of

analysts covering all publicly held companies. But

even if analyst coverage in concentrated ownership

regimes were equivalent to that in dispersed ownership systems, the analysts predictions of the firms

future earnings or value would still mean less to

public shareholders if the controlling shareholder

remained in a position to squeeze-out the minority

shareholders.

J. C. Coffee, Jr

shareholders at Parmalat. 32 Similarly, European

companies with dispersed ownership have engaged in US-style earnings management.33 The

point then is that, across different legal regimes,

the structure of share ownership likely determines the nature of the fraud. The bottom line for

regulators is this: show us the structure of share

ownership, and we can predict the likely scenario

for fraud and abuse.

Public policy thus needs to start from the recognition

that dispersed ownership creates managerial incentives to manipulate income, while concentrated

ownership invites the low-visibility extraction of

private benefits. As a result, governance protections that work in one system may fail in the other.

Even more importantly, different gatekeepers need

to be designed into different governance systems to

monitor for different abuses.

Anderson, K. L., and Yohn, T. L. (2002), The Effect of 10K Restatements on Firm Value, Information Asymmetries,

and Investors Reliance on Earnings, available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=332380

Atanasov, V., Ciccotello, C. S., and Gyoshev, S. B. (2005), How Does Law Affect Finance? An Empirical Examination

of Tunneling in an Emerging Market, William Davidson Institute Working Paper No. 742, available at http:/

/ssrn.com/ abstract=423506

Banner, S. (1997), What Causes New Securities Regulation? 300 Years of Evidence, Washington University Law

Quarterly, 75(2), 849.

Barca, F., and Becht, M. (eds) (2001), The Control of Corporate Europe, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Bertrand, M., Mehta, P., and Mullainathan, S. (2000), Ferreting Out Tunneling: An Application to Indian Business

Groups, MIT Dept of Economics Working Paper No. 00-28, available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=246001

Cheng, Q., and Warfield, T. (2004), Equity Incentives and Earnings Management, available at http://ssrn.com/

abstract=457840

Coffee, J. C., Jr. (2001), The Rise of Dispersed Ownership: The Roles of Law and the State in the Separation of Ownership

and Control, Yale Law Journal, 111(1), 182.

(2004a), Gatekeeper Failure and Reform: The Challenge of Fashioning Relevant Reforms, Boston University

Law Review, 84(2), 30164.

(2004b), What Caused Enron?: A Capsule Social and Economic History of the 1990s, Cornell Law Review,

89(2).

Denis, D. J., Hanouna, P., and Sarin, A. (2005), Is There a Dark Side to Incentive Compensation?, available at http:/

/ssrn.com/abstract=695583

Desai, H., Krishnamurthy, S., and Venkataraman, K. (2004), Do Short Sellers Target Firms with Poor Earnings Quality?:

Evidence from Earnings Restatements, available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=633283

Dyck, A., and Zingales, L. (2004), Private Benefits of Control: An International Comparison, Journal of Finance, 59(2),

537600.

Edwards, F., and Canter, M. (1995), The Collapse of Metallgesellschaft: Unhedgeable Risks, Poor Hedging Strategy,

or Just Bad Luck, Journal of Futures Markets, 15(3), 21164.

Edwards, J., and Fischer, K. (1994), Banks, Finance and Investment in Germany, Cambridge, Cambridge University

Press.

Efendi, J., Kinney, M. R., and Swanson, E. P. (2005), Can Short Sellers Predict Accounting Restatements?, AAA 2005

FARS Meeting Paper, available at http://ssrn.com/abstract= 591361

Srivastava, A., and Swanson, E. P., (2004), Why Do Corporate Managers Misstate Financial Statements: The

Role of Option Compensation, Corporate Governance and Other Factors, available at http://ssrn.com/

abstract=547920

Ehrhardt, O., and Nowak, E. (2003), Private Benefits and Minority Shareholder Expropriation (or What Exactly Are

Private Benefits of Control), EFA Annual Conference Paper No. 809, available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=423506

Adelphia Communications went into bankruptcy after it was discovered that it had made undisclosed loans and loan guarantees

of at least $3.1 billion to its founders family. This closely resembles Parmalat in that the fraud involved both the balance sheet

and diversions to the founders family. In bankruptcy, Adelphia sued its former auditors, Deloitte & Touche, for allegedly failing

to disclose or investigate Adelphias loans to the Rigas family. See Frank (2002).

33

For examples, see section III, para. 3.

32

209

Downloaded from http://oxrep.oxfordjournals.org at Hong Kong Polytechnic University on May 18, 2010

REFERENCES

OXFORD REVIEW OF ECONOMIC POLICY, VOL. 21, NO. 2

210

Downloaded from http://oxrep.oxfordjournals.org at Hong Kong Polytechnic University on May 18, 2010

Ferrarini, G., Moloney, N., and Vespro, C. (2003), Executive Remuneration in the EU: Comparative Law and Practice,

ECGI Working Paper.

Fisher, A. (1995), Metallgesellschaft: The Oil Deals That Crippled a German Metal-trading Giant, Financial Times,

20 March, 20.

FitchRatings (2005), Accounting and Financial Reporting Risk: 2005 Global Outlook, 14 March.

Frank, R. (2002), Adelphia Sues Deloitte & Touche, Accusing Former Auditor of Fraud, Wall Street Journal, 7

November, A2.

Franks, J., and Mayer, C. P. (1997), Corporate Ownership and Control in German, the UK and France, Journal of

Applied Corporate Finance, 9(4), 30.

Galloni, A., and Reilly, D. (2004), How Parmalat Spent and Spent, Wall Street Journal, 23 July.

Gordon, J. N. (1999), Pathways to Corporate Convergence?: Two Steps On the Road to Shareholder Capitalism in

Germany, Columbia Journal of European Law, 5(219).

Gorton, G., and Schmid, F. A. (1996), Universal Banking and the Performance of German Firms, National Bureau of

Economic Research Working Paper No. 5453.

Griffin, P. A. (2002), A League of Their Own? Financial Analysts Responses to Restatements and Corrective

Disclosures, available at http://ssrn.com/abstract= 326581

Hall, B. J. (2003), Six Challenges in Designing Equity-based Pay, Accenture Journal of Applied Corporate Finance,

15(3), 21.

Hollinger International (2004), Report of Investigation by the Special Committee of the Board of Directors of Hollinger

International Inc, 30 August.

Holmstrom, B., and Kaplan, S. (2003), The State of US Corporate Governance: Whats Right and Whats Wrong,

Accenture Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 15(3), 8.

Huron Consulting Group (2003a), An Analysis of Restatement Matters: Rules, Errors, Ethics, for the Five Years Ended

December 31, 2002.

(2003b), 2003 Annual Review of Financial Reporting Matters.

(2005), New Report by Huron Consulting Group Reveals Financial Restatements Increased at a Record Level

in 2004, Press Release, 19 January.

Johnson, J. (2004), Vivendi Probe Ends With Euro $1 Million Fine for Messier, Financial Times, 8 December, 31.

Johnson, S. A., Ryan, H. E., Jr, and Tian, Y. S. (2003), Executive Compensation and Corporate Fraud, available

at http://ssrn.com/abstract=395960

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., and Shleifer, A. (2000), Tunneling, American Economic Review, 90(2), 227.

Kirchmaier, T., and Grant, J. (2004a), Financial Tunneling and the Revenge of the Insider System: How to Circumvent

the New European Corporate Governance Legislation, available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=613945

(2004b), Corporate Ownership Structure and Performance in Europe, CEP Discussion Paper No. 0631,

available at http://ssrn.com/ abstract=616201

La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., and Vishny, R. W. (1999), Corporate Ownership Around the World,

Journal of Finance, 54(2), 471517.

Leonard, D. (2004), More Trials for Lord Black, Fortune, 4 October, 42.

Littleton, A. C. (1988), Accounting Evolution to 1900, University of Alabama Press.

McCoy, K. (2005), Prosecutors Charge Nine More in Royal Ahold Case, USA Today, 14 January, 1B.

Melis, A. (2004), Corporate Governance Failures. To What Extent is Parmalat a Particularly Italian Case?, available

at http://ssrn.com/abstract=563223

Ming, J. J., and Wong, T. J. (2003), Earnings Management and Tunneling through Related Party Transactions:

Evidence from Chinese Corporate Groups, EAA 2003 Annual Conference Paper No. 549, available at http://

ssrn.com/abstract=42488

Morgenson,G. (2004), Explaining (Or Not) Why the Boss Is Paid So Much, New York Times, 25 January, 3, 1.

Moriarty, G. B., and Livingston, P. B. (2001), Quantitative Measures of the Quality of Financial Reporting, Financial

Executive, July/August, 534.

Nenova, T. (2000), The Value of Corporate Votes and Control Benefits: A Cross-country Analysis, available

at http://ssrn.com/abstract=237809

OConner, S. M. (2004), Be Careful What You Wish For: How Accountants and Congress Created the Problem of

Auditor Independence, Boston College Law Review, 45(4), 741828.

Peng, L., and Roell, A. (2004), Executive Pay, Earnings Manipulation and Shareholder Litigation, AFA Philadelphia

Meetings, December, available at http://ssrn.com/ abstract=488148

Richardson, S., Tuna, I., and Wu, M. (2002), Predicting Earnings Management: The Case of Earnings Restatements,

available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=338681

J. C. Coffee, Jr

Roe, M. J. (1998), German Co-determination and German Securities Markets, Columbia Business Law Review, 1, 167.

SEC (2003), Report Pursuant to Section 704 of the SarbanesOxley Act of 2002, Washington, DC, Securities and

Exchange Commission.

Simonian, H. (2004), Europes First Victim of SarbanesOxley? Corporate Governance: Adecco was Pilloried for its

Poor Handling of US Accounting Problems, Financial Times, 29 January, 14.

GAO (2002), Financial Statement Restatements: Trends, Market Impacts, Regulatory Responses and Remaining

Challenges, Washington, DC, US General Accounting Office, Pub. No. 03-138.

Wenger, E., and Kaserer, C. (1998), German Banks and Corporate GovernanceA Critical View, in K. Hopt et al. (eds),

Comparative Corporate GovernanceThe State of the Art and Emerging Research, Oxford, Clarendon Press.

Zingales, L. (1995), What Determines the Value of Corporate Votes?, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110(4), 1047

73.

Downloaded from http://oxrep.oxfordjournals.org at Hong Kong Polytechnic University on May 18, 2010

211

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Apple: Corporate Governance and Stock Buyback: Company OverviewDocumento11 pagineApple: Corporate Governance and Stock Buyback: Company OverviewKania BilaNessuna valutazione finora

- Ethics & Financial Reporting in United StatesDocumento9 pagineEthics & Financial Reporting in United StatesMathilda ChanNessuna valutazione finora

- Starbucks - Porter 5 Forces AnalysisDocumento2 pagineStarbucks - Porter 5 Forces AnalysisMathilda ChanNessuna valutazione finora

- Starbucks 4Documento59 pagineStarbucks 4Amirul Irfan100% (3)

- Budgeting and Standard CostDocumento13 pagineBudgeting and Standard CostMathilda ChanNessuna valutazione finora

- BPS10 - Understanding Corporate GovernanceDocumento25 pagineBPS10 - Understanding Corporate GovernanceMathilda ChanNessuna valutazione finora

- Earnings ManagementDocumento32 pagineEarnings ManagementMathilda ChanNessuna valutazione finora

- Appendix 14: Code On Corporate Governance PracticesDocumento24 pagineAppendix 14: Code On Corporate Governance PracticesMathilda ChanNessuna valutazione finora

- Is Confucianism Good For Business Ethics in ChinaDocumento16 pagineIs Confucianism Good For Business Ethics in ChinaMathilda ChanNessuna valutazione finora

- Investment Banking Research by ValueAddDocumento10 pagineInvestment Banking Research by ValueAddValueadd ResearchNessuna valutazione finora

- Claw Assignment NewestDocumento6 pagineClaw Assignment NewestclaraNessuna valutazione finora

- Untitled Spreadsheet - Sheet1Documento5 pagineUntitled Spreadsheet - Sheet1Scientist 235Nessuna valutazione finora

- Mamy Poko XXXL - Google SearchDocumento1 paginaMamy Poko XXXL - Google SearchTio Roby, S.Sn., M.SnNessuna valutazione finora

- Partnership in PakistanDocumento20 paginePartnership in Pakistanbonfument73% (11)

- 5th Year Buscom For DiscussionDocumento5 pagine5th Year Buscom For DiscussionAirille CarlosNessuna valutazione finora

- G-Cloud 6 Customer Numbers Sheet1 PDFDocumento29 pagineG-Cloud 6 Customer Numbers Sheet1 PDFAnonymous 8Dj1zKd1ugNessuna valutazione finora

- Public Notice02082018Documento1 paginaPublic Notice02082018Anonymous FnM14a0Nessuna valutazione finora

- Tony Robbins Delivers Personal Power: Dean's Award To Recognize Exceptional LeadershipDocumento2 pagineTony Robbins Delivers Personal Power: Dean's Award To Recognize Exceptional LeadershipMuhammad AliNessuna valutazione finora

- Consolidado StockDocumento490 pagineConsolidado StockMagoKanduNessuna valutazione finora

- Due Diligence Report Format Final WebsiteDocumento9 pagineDue Diligence Report Format Final WebsiteKumar GauravNessuna valutazione finora

- 6 Months Statement Axis BankDocumento34 pagine6 Months Statement Axis Bankhariomsingh.karnisenaNessuna valutazione finora

- FAQ On Layers On Subsidiaries 1Documento15 pagineFAQ On Layers On Subsidiaries 1Rohit JainNessuna valutazione finora

- Polaroid Corporation ENGLISHDocumento14 paginePolaroid Corporation ENGLISHAtul AnandNessuna valutazione finora

- Purplebook Search February Data DownloadDocumento384 paginePurplebook Search February Data DownloadEko YuliantoNessuna valutazione finora

- PE in China EY May2011Documento20 paginePE in China EY May2011pareshsharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- In The United States Bankruptcy Court Eastern District of Michigan Southern DivisionDocumento4 pagineIn The United States Bankruptcy Court Eastern District of Michigan Southern DivisionChapter 11 DocketsNessuna valutazione finora

- About Privet Banking Sector in IndiaDocumento11 pagineAbout Privet Banking Sector in IndiaRakesh MalusareNessuna valutazione finora

- Retained Earnings Sample QuizDocumento9 pagineRetained Earnings Sample QuizGali jizNessuna valutazione finora

- List of Banks in IndiaDocumento5 pagineList of Banks in IndiamahendranmaheNessuna valutazione finora

- Septiembre 2017 PDFDocumento383 pagineSeptiembre 2017 PDFmmoreno_184442Nessuna valutazione finora

- 2007 Resume Book Tuck PDFDocumento92 pagine2007 Resume Book Tuck PDFpokeefe09Nessuna valutazione finora

- Credit Card ProvidersDocumento6 pagineCredit Card ProvidersVijay Pal SinghNessuna valutazione finora

- Activity 4Documento13 pagineActivity 4Lala FordNessuna valutazione finora

- New ContactsDocumento8 pagineNew ContactsRoshani BhandariNessuna valutazione finora

- UK - CXO - Customer ExperienceDocumento11 pagineUK - CXO - Customer ExperienceSheel ThakkarNessuna valutazione finora

- MCQ Law Ca InterDocumento71 pagineMCQ Law Ca InterGaurav PatelNessuna valutazione finora

- Dunlop India Limited 2012 PDFDocumento10 pagineDunlop India Limited 2012 PDFdidwaniasNessuna valutazione finora