Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

A Comparison of Three Methods For Eliminating

Caricato da

ALEJANDRO MATUTETitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

A Comparison of Three Methods For Eliminating

Caricato da

ALEJANDRO MATUTECopyright:

Formati disponibili

(SUMMER 19 74)

A COMPARISON OF THREE METHODS FOR ELIMINATING

DISRUPTIVE LUNCHROOM BEHAVIOR1' 2

EVELYN M. MACPHERSON, BENJAMIN L. CANDEE,

JOURNAL OF APPLIED BEHAVIOR ANALYSIS

1974, 7,1 287-297

NUMBER

AND ROBERT J. HOHMAN

CLEVELAND, OHIO PUBLIC SCHOOLS AND BOWLING GREEN UNIVERSITY

Three methods of controlling disruptive lunchroom behaviors of elementary school

children were compared: basic modification procedures, basic modification procedures

plus punishment essays, and basic modification procedures plus mediation essays.

During an in-service workshop, six paraprofessional lunch aides received training in

these methods to modify three classes of disruptive lunchroom behaviors. They then

applied the methods in a counter-balanced design. Fourth- and fifth-grade elementary

school pupils were observers and made reliability counts of the target misbehaviors

under the various methods. Results indicated that during the periods when aides had

been directed to use basic modification procedures plus mediation essays, target misbehaviors were almost totally eliminated and occurred significantly less often than

during the periods when they had been directed to use basic modification procedures

alone or basic modification procedures plus punishment essays.

Lunch-period group-management problems

are becoming increasingly prevalent in city elementary schools as more children eat their

lunches at school, rather than at home. The

methods of managing lunchroom behavior include counselling, parent conferences, student

council programs, adult lecturing, and controls

such as detention after school, suspension of

lunch privileges, and physical punishment. Yet,

these methods often fail to produce lasting

effects.

Frequently, pupil misbehavior can result in

lunch aides becoming discouraged, responding

antagonistically toward the children, or even

resigning their jobs. The classroom teacher receiving the pupils after lunch often has

the added task of reestablishing appropriate

behaviors.

Classroom studies demonstrate that the fre1The authors gratefully express their appreciation

to Professor Ralph 0. Blackwood, University of

Akron and Dr. Theodore R. Warm, University Hospitals of Cleveland. We wish to thank Mattie Alderman, Theresa Cirtwell, Josie Martin, Eleanor

Rogers, Gloria Seneff, and Helen Zajac for their

roles in this investigation. The 12 student observers

deserve thanks for their conscientious work.

2Reprints may be obtained from Evelyn Mac-

quency of deviant behaviors of both individuals

and groups can be reduced by using operant

principles that make reinforcers contingent

upon appropriate responses (Blackwood, 1971;

Hall, Fox, Willard, Goldsmith, Emerson, Owens, Davis, and Porcia, 1971; Herman and

Tramontana, 1971; Schutte and Hopkins, 1970;

Zimmerman and Zimmerman, 1962). Parents

(Zeilberger, Sampen, and Sloane, 1968), paraprofessionals (Miller and Schneider, 1970),

teachers (Madsen, Becker, and Thomas, 1968),

and counsellors (Hinds and Roehlke, 1970)

have applied operant techniques successfully.

Although the reported decreases in the frequency of disruptive behaviors are significant

and impressive (e.g., a 68%,, decrease reported

in Madsen et al., 1968), a number of misbehaviors often continue to be emitted. A method

involving verbal mediation training to teach

self-control gives promise of reducing further

the frequency of pupil misbehavior (Blackwood, 1970, 1972). Speech is analyzed as verbal chaining, which produces stimuli that are

both conditioned reinforcers and discriminative

stimuli. From this analysis of speech, one can

suggest a method of teaching self-control with

mediation essays, in which students, when

tempted to misbehave, are taught to describe to

Pherson, Principal, Mound School, Cleveland, Ohio

44105.

287

EVELYN M. MacPHERSON et al.

288

themselves the consequences of appropriate and

inappropriate behavior.

The present study developed a plan for using

mediation essays to help eliminate unacceptable

lunchroom behaviors in elementary school children. The results of using a basic modification

plan were compared with those of using a basic

modification plan plus mediation essays and

with those of using a basic modification plan

plus punishment essays.

METHOD

Subjects and Setting

The study, conducted at Mound Elementary

School, Cleveland, Ohio, involved 221 children,

6 to 13 yr of age. The subjects were allowed to

eat home-prepared lunches at school as a convenience to working parents. The subjects were

grouped by age level into six lunchrooms with

approximately 38 children each. The hour-long

lunch period was broken into three time segments: (a) lavatory period, 10 min, (b) eating

time, 20 min, and (c) recreation, 30 min.

Six aides, housewives in the neighborhood,

were hired by the principal to supervise the

noontime program, based upon the principal's

judgement of their concern for children and

their ability to interact effectively with them

(cf. Sandler, unpublished). The aides had no

previous formal training in group management.

Design

To determine the misbehaviors most disturbing to the aides, a six-point rating scale of 10

lunchtime misbehaviors was submitted to each

aide. The three misbehaviors receiving the highest mean rating, talking while the aide speaks,

out-of-seat, and quarreling, were selected as the

target misbehaviors. Talking while aide speaks

involved a child speaking, shouting, or whispering while the lunch aide gave a group direction

or made an announcement. Quarreling was defined as a child verbally or physically annoying

another child, disrupting an activity by throwing

or snatching a player's equipment, name calling,

or shouting verbal disagreements while eating,

or engaging in one of the reinforcement activities. Out-of-seat was defined as a child having

no contact between his seat and his chair. Outof-seat was not coded as misbehavior when the

subject was granted permission by the aide to

move from one activity to another, or when the

activity required

movement.

The six lunchrooms were divided into three

groups with two classrooms each. In each group,

the three conditions, basic modification plan

(BMP), basic modification plan plus punishment essays (BMP + PE), and basic modification plan plus mediation essays (BMP + ME),

were presented in different sequences. Each

lunchroom was randomly paired with another,

and the pair was then randomly assigned to one

of the experiments.

Following a nine-day Baseline period, the

paired groups were exposed in varying sequences to each condition as follows: Group I:

BMP + PE, BMP, BMP + ME; Group II:

BMP, BMP + ME, BMP + PE; Group III:

BMP + ME, BMP + PE, BMP. Each condition

in the sequence lasted 10 days. All groups were

then to complete the study with 40 more days

of condition BMP + ME, a five-day Postcheck

with condition BMP + ME, 40 days more of

condition BMP + ME, a five-day Reversal period, and a second five-day Postcheck with

condition BMP + ME. Continuous frequency

counts of the target misbehaviors were planned

for all periods except for the 20 days of condition BMP + ME immediately before, and the

40 days of condition BMP + ME immediately

after, the first Postcheck.

Group discussion of the three target behaviors

was conducted by the aide in each lunchroom

immediately following the Baseline period. The

behaviors were specifically defined for the students and concrete examples were given by the

aide.

After the second Postcheck, the questionnaire

used to select the target misbehaviors was again

administered to the aides.

ELIMINATING DISRUPTIVE LUNCHROOM BEHAVIOR

The third experimental condition was shortened to five days at the request of the aides in

Experiments II and III. They had obtained relief

from disruptive behaviors with Condition

BMP + ME, had found these behaviors increasing in subsequent conditions BMP and BMP +

PE, and had requested that the third condition

be limited to one week so they could implement

condition BMP + ME.

Aides' training program. Individually, the

aides were asked to learn "ways to help your

lunch children behave better and relieve you of

settling so many noontime disturbances". Unanimously, the aides agreed to participate in fourteen 15-min operant conditioning in-service

training sessions conducted by the building principal. Basic behavioral principles relating to

each condition were discussed before they were

applied. Topics included causes of misbehaviors,

response acquisition and extinction, reinforcement and reinforcers, satiation and deprivation,

punishment, and mediation. Appropriate portions of Blackwood's (1971) text were paraphrased and used in the discussion and study

sessions.

Although some of the training sessions overlapped with the experiments, premature application was discouraged by requesting that the procedures not be applied until the treatment

condition and by not making available the essay

materials until the appropriate condition.

Observer training. Twelve elementary students, age 9 to 11 yr, were selected from teacher

recommendations to record the frequency of the

target behaviors. They were paired and trained

in observational techniques during the four preBaseline practice sessions conducted in the

lunchrooms. Tokens, made available contingent

upon appropriate observer performance, could

be exchanged for a variety of stimuli including

early lunch period, free time, extra library and

gym, candy and snacks, milk treats, and the use

of movies, film strips, a tape recorder, listening

center, TV, and radio.

During the planning stage and Baseline condition, the observers were rewarded both socially

289

and with tokens immediately after each session.

They were switched to a variable-interval schedule following Baseline.

Recording procedures. The observers were

randomly assigned by pairs to each of the lunchrooms. The two observers sat at opposite sides

of the room, with an unobstructed view of the

children and the aide. They avoided eye contact

or interaction with the children during recording periods. During Reversal and Postcheck2,

the observers were randomly regrouped and reassigned to different lunchrooms as a reliability

check.

For each 60-min lunch period during the

study, each observer independently recorded

each occurrence of the target behaviors.1 Each

recording sheet was divided into three rows of

12 squares each, one row for each target behavior. Each box in the row was numbered 12, 1,

2, 3 ... 11 corresponding to the figures upon a

clock face to simplify recording of the target

behaviors. One tally mark was made for each

occurrence of a defined misbehavior in the appropriately numbered box corresponding to the

5-min interval during which it was emitted.

Conditions

Baseline. During Baseline, the aides were requested to manage the children as before, not

introducing the procedure discussed during the

workshops.

Basic Modification Plan (BMP). Three basic

procedures were in effect in this condition. (1)

Positive reinforcement, the withdrawal of reinforcement, aides' attention, aides' praise, and

special-privilege activities were to serve as reinforcers and were to be made contingent upon

a pupil's appropriate behavior. (2) Reinforcers

were to be withheld for the day if a child continued to emit the same type of misbehavior

after once being instructed to stop. The specialprivilege reinforcers included gym time, movies,

'The various reinforcement strategies were, of

course, implemented by the aides on the basis of their

perception of pupil target behavior and not on the

basis of the observers' tally.

290

EVELYN M. MacPHERSON et al.

outdoor play, TV, children's card games, lotto,

checkers and chess, weaving, model building,

drawing, clay modelling, dance sessions, dramatizations, and story time. (3) If a child continued to emit the same target misbehavior for

more than three times during any one session

after being verbally reminded and/or silently

signalled by his aide to stop, a timeout was introduced. The child was directed by the aide to

a clean, heated, well-lit but windowless 8 by 10

ft (2.4 by 3 m) former storeroom, adjacent to

the lunchrooms, equipped only with a chair. He

was told he could report back to his aide for

permission to re-enter the lunchroom when he

could control his misbehavior. The aides were

instructed to limit timeout to a maximum of 5

min for the 9- to 12-yr olds and 3 min for the

younger children. However, the aides never had

to return to the timeout room to bring a child

back. All such children returned to their aides

before the unannounced time limit.

Basic Modification Plan plus Mediation Essays (BMP + ME). In mediation training, a

child is instructed to verbalize the consequences

of his two alternative behaviors at the time he

is tempted to misbehave. The mediation essays

present a catechism of four questions with answers (Blackwood, 1970) that itemize the consequences of both the specific misbehavior and

acceptable behavior. The first question and answer concerns the definition of the misbehavior.

This is followed by three more questions and

answers, which set up a discrimination procedure by (a) itemizing the aversive consequences

of the behavior, (b) describing the behaviorally

stated appropriate response, and (c) describing

the consequences of appropriate behavior.

Six different essays were constructed for each

of the three target behaviors. Thus, each grade

level from one through six had a graded, vocabulary controlled essay (Botel, 1962). Each

of the six essays emphasized the gain and loss

to the child of playing with lunch mates, using

the gym and play yard, making friends, and

pleasing his parents.

This is a copy of the third-grade mediation

essay dealing with the target behavior "talking

while the aide is speaking":

"What did I do wrong?

I talked while the aide was talking.

What things happen I don't like when I

talk out?

I don't have any fun at lunch when I

talk out. I must write these answers. I

won't have time to go to the gym. The

aide cannot take me outside. I can't play

with the balls.

What should I do?

I should be quiet when the aide is

talking.

What pleasant things happen when I

quietly listen to the aide?

I can do fun things I like. I can go to the

gym and play games. I can go outside

with the other kids. I can play with the

balls. I may be picked to help the aide.

Mother and Father will be happy when

they hear I am good. The kids will like

me and want me to be their friend."

On the first day that this condition was initiated, the aides defined the target behaviors

with the children and explained and discussed

with them the procedures to be used.

Each time a child emitted a target misbehavior during this condition, he was requested not

more than twice by the aide to improve his response. If he persisted in that particular misbehavior, an essay was assigned by the aide. The

essay was to be copied and returned by the end

of the hour. Failure to complete the assignment

or arguing with the aide resulted in a second

assignment. If two copies of the essay were not

returned promptly, the school office notified the

parents that lunch privileges might be suspended unless the child completed the assignment on the third day.

This essay-copying assignment could be assigned to a child three times per target behavior.

When further assignment was needed, the child

was to paraphrase the essay for the second three

infractions. For the third set of infractions, the

ELIMINATING DISRUPTIVE LUNCHROOM BEHAVIOR

291

Postchecki. Postcheck1 was made beginning

child was to compose the essay from memory.

The treatment plan provided role-playing as a on the seventy-fifth day, four weeks after the

procedure to follow for the tenth and subse- mediation condition ended, and lasted five days.

Reversal. This five-day condition began on

quent infractions.

During this condition, 82 mediation essays the one hundred and twentieth day of the study,

were assigned: 26 for talking while the aide after an eight-week suspension of observations.

speaks, 35 for out-of-seat, and 21 for quarreling. The aides, at first reluctant to withhold reinOf this total, four children were assigned to forcement, were encouraged by the principal to

make two copies of the same essay; none was reinstate the management methods they had

used during the Baseline condition of often verassigned to make three copies.

Basic Modification Plan plus Punishment Es- bally reprimanding the child contingent upon

says (BMP + PE). Traditionally, many teach- inappropriate responses and frequently ignoring

ers have imposed additional work tasks as pun- appropriate behaviors.

Postcheck2. Postcheck2 was initiated on the

ishment for misbehaving students, anticipating

that the extra task will result in a change in the one hundred and twenty-fifth day, immediately

child's behavior. Such tasks as assigning extra following Reversal, and lasted for five days.

math problems, writing spelling words 10, 20,

or more times, or copying sentences such as "I

RESULTS

will not chew gum in school" 50 times or more

Interobserver reliability. Since the daily frehave not been very effective in eliminating the

punished behavior. The authors have failed to quency of one target misbehavior in one lunchfind any evidence in the psychological and edu- room varied from a low of zero to a high of

cational literature to support the effectiveness 184, two separate reliability indexes were

of such methods. To evaluate the deterring deemed necessary: one for the cases where the

power of this type of assignment, this condition frequency of any one target behavior for the

used the basic modification plan plus punish- day was tallied by either pupil observer as five

or more, and the other for those cases where the

ment essays.

Six different punishment essays were con- frequency count was below five for both obstructed, one for each grade level. The material servers.

One index was calculated by noting the numused was selected from a health text and several

children's trade books available in most school ber of 5-min intervals on the day in question

libraries. During this condition, 132 punishment during which observations were made, and then

essays were assigned: 31 children being assigned counting the number of these intervals in which

to make two copies of the same essay and 17 to the two observers agreed on the exact frequency

-including zero-of the target behavior. This

make three copies.

The procedure to be followed by the aides in latter number of intervals was then divided by

assigning punishment essays was identical to the former number of intervals to obtain the

that used with the mediation essays; however, index.

To check the possibility that the partners in

paraphrasing, memorization, and role-playing

were not to be used in this condition.

pairs of observers might have come to agree

Both punishment and mediation essays for erroneously on the scoring of the occurrence or

grades one through three were double-spaced nonoccurrence of target events, the pupil oband mimeographed, using primer-size type. The servers were assigned to different pairs during

upper-grade essays used elite-size type and were the final two weeks of the study. The indexes

single spaced. All essays were shorter than one of reliability for the new pairs were similar to

those of the original pairs.

page.

292

EVELYN M. MacPHERSON et al.

TAIlIS WHILIE

AMIE

SPEAKS

HU1T-0 F- SEAT

above

..

2

6"

II

II

ii

ii

ii

ii

I-!

I~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ I

;,.3'l; A35 ,A 43, 45,

!

plns

Hasig ledification

Mdifitatill

lasighgigiepoaaio,

,us

Plan

mediation Essays

!e

+1X5 t; fE2'5

Pnlishk lt isv

SH1E

DA YT

E RI

S

0S

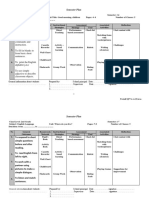

Fig. 1. Average number of misbehaviors per session for each of the three target behaviors of Experiment I.

Three separate vacation periods occurred during the duration of the study; i.e., two days between the ninth

and tenth days (Thanksgiving), 10 days between the twenty-third and twenty-fourth days (Christmas), and

six days between the forty-second and forty-third days (Spring Break). Additional breaks in observing and

tallying occurred for 20 days (period 55 through 74) preceding Postcheck1 and 40 days (period 80 through

119) between Postcheck, and Reversal. The baseline point above 60 for talking while the aide speaks for the

younger children reached an average of 61. For the same age group, the baseline data for quarreling behavior

ranged from 61 to 87, with an average of 74.

293

ELIMINATING DISRUPTIVE LUNCHROOM BEHAVIOR

Of the 1242 (69 days X 6 observer pairs X of indicies was above 90% for all pairs of

3 target misbehaviors) separate measures of re- observers.

A simpler method for estimating interobliability computed, none fell below 65%, and

the median percentage agreement for both types server agreement was to obtain the total count

kil

TALK III

Go

40

30'

Will E 1IE

SPE A KS

i!i!

'I

ElxP. I I

Ages-

*

0

10

.:

"

20.

_

l0

-honof_OW144

LAL%-&

I

one

a I Z--fI H=.

..

.f

.1

_..

If t

;?IV --jolA

AMeJ

Y-

N

I

!II!

!i

, .

30

-30

20'

10.

-60

60

~~~ : I ~a

JO'

sI

I_

20.

10.

hselil

A

3%

S} ''7'SY

A''

2' ''h%

A'

I5 ''1 s

Pest

BMWe NfigUtie puts

Rai$ luifinite ileNeliliugmelhie

Plu

Ciek

I

Essas

MANm

esi

Nodii

+

Cetiee

NeiBti

b

aF

III

133

Iwrsl hsP

CMek2

I E I A Y P E 11 IIS

Fig. 2. Average number of lunchtime misbehaviors per day for each of the three target behaviors of Experiment II. Two baseline points above 60 average misbehaviors for the older children for talking while the

aide speaks were 63 and 67. For this same group, the baseline data for out-of-seat behavior ranged from 64

to 140, with an average of 92. For the younger group, the baseline data for out-of-seat behavior ranged from

75 to 122, with an average of 85. For this same group and same misbehavior, the BMP + PE data ranged

from 62 to 184, with an average of 125.

EVELYN M. MacPHERSON

294

for each type of misbehavior during each experimental condition for each observer, and

then for each pair of observers to divide the

smaller count by the larger. When this was

done, the mean percentage agreements for the

six original pairs varied from 92.3 to 95.8%,

and for the six reconstituted pairs, from 86.2 to

96.0%.

Frequency of target misbehaviors under various experimental conditions. Figures 1 through

3 show the daily frequencies of target misbehaviors for the six experimental groups during

the various treatment periods. In cases where

the paired observers were not in complete agreement on daily frequency counts, the mean of the

two tallies was used. Although daily frequencies

per group actually vary from zero to 184, all

frequencies above 60 are plotted at the same

height for ease of graphing.

It is clear from these graphs that a significantly smaller number of target misbehaviors

was emitted during condition BMP than during

any other experimental condition. The graphs

also show that the misbehaviors for all groups

increased during the reversal condition. Further,

all six lunchroom groups appear to have responded similarly to the condition regardless of

pupils' age levels, aides' personal attributes, or

the order in which the conditions were introduced.

Because of this similarity of response, the data

from all groups were combined in Table 1,

which shows the overall daily frequency of mis-

et

al.

behaviors during the main phases of the study.

Using the data in the last column of Table 1,

one can compute the percentage reductions of

Baseline frequency of misbehaviors associated

with the various conditions. Under condition

BMP + PE, the Baseline frequency is reduced

by about 22%; under condition BMP, it is reduced by about 58%; and under condition

BMP + ME, it is reduced by over 90%. As condition BMP + ME is extended, the reduction

approaches 100%.

Timeout use and effectiveness. Timeout was

most frequently imposed by the aides during

BMP + PE: an average of 53 times in Experiment I and 60 times in Experiment III for the

two 10-day periods, and 24 times in Experiment

II for the five-day period. When BMP was in

effect, timeout use averaged 22 times and 28

times for the 10-day periods of Experiments I

and II and seven times for the five-day period

of Experiment III. The greatest reduction of its

use occurred during BMP + ME: an average

of four and of two times for the 10-day periods

of Experiments II and III, an average of two

times and of once for the 20-day periods of Experiments II and III, and five times for the 25day period of Experiment I. None of the aides

used this procedure during Post Checki, Post

Check2, or Reversal, because they said mediation essays were, for them, easier to administer

and a more effective method in reducing the

misbehaviors.

Changes in aides' perceptions of most disturb-

target

Table 1

Frequency of Target Misbehaviors Per Day for All Six Lunchrooms Combineda

All Target

Conditions

Baseline

Basic Modification Plan (BMP)

BMP plus Punishment Essays (PE)

BMP plus Mediation Essays (ME)b

Reversal

BMP plus Mediation Essays (ME)c

a221 children

bFirst 10 days of treatment

CFive days of Postcheck2

Talking Out-of-Seat Quarreling Misbehaviors

155

78

127

11

62

0

303

87

225

31

102

0

131

82

110

9

48

1

589

247

462

51

212

1

295

ELIMINATING DISRUPTIVE LUNCHROOM BEHAVIOR

II

Ii

above

501

40!

30:'

20-

lsl

::

eiifuilseiiai

Ieilfutl

I1

Af

I1

0

r

Bolaigjg

rnalh

W

10

hii

25

"'Ae i

i

3asie110fistilee 1a~i

eiatiel Ess

3m

la1516 dif~icaili pigs

i

i~s

1dia*h Naiulyt

Emu

Fhit

Cheek

PIOnI8 PeSt

Cheek2

I3I E I I Y PE I 3I3S

Fig. 3. Average number of lunchtime misbehaviors per day for each of the three target behaviors of Experiment III. The baseline point above 60 average misbehaviors for the younger children for talking while

the aide speaks was 64. For this same group, the baseline data for out-of-seat ranged from 72 to 80, with

an average of 85. The two BMP + PE points for this same group and same behavior were 68 and 69.

The BMP + PE point for this group for quarreling behavior was 84. For the older children for out-of-seat

behavior, the baseline point was 105 and the two BMP + PE points were 66 and 95.

296

EVELYN M. MacPHERSON et al.

ing pupil behaviors. At the conclusion of the

study, the aides were readministered the questionnaire initially used to identify the target misbehaviors. None of the six aides selected the

original target behaviors as being most disturbing, ranking them eighth, ninth, and tenth on

the 10-item questionnaire. Instead, they rated

giggling, following directions, and shouting as

the three behaviors now most in need of

modification.

DISCUSSION

The addition of mediation essays, but not of

punishment essays, seemed to add to the effectiveness of the basic modification plan in reducing the frequency of target behaviors. These

results provide evidence for the validity of

Blackwood's hypotheses (Blackwood, 1972)

concerning mediation training. However, there

are a number of alternative explanations for the

superiority of condition BMP + ME in this

study.

It is possible that mediation essays were effective because they functioned as aversive stimuli. Since 96%,, of the assigned mediation essays

involved only the copying of the essay, it would

appear that it was no more a punisher than the

copying of the punishment essay, which was

shown to be ineffective.

Although only a small minority of the pupils

were actually assigned to copy mediation essays,

target misbehaviors for the entire sample

dropped to almost zero. A possible explanation

is that since the pupils were not naive in the

use of mediation essays, and since the specific

mediation essays used in this study were read in

the lunchroom and discussed by the aide at the

beginning of condition BMP + ME they were

effective through the process of pupil rehearsal

during the periods of temptation. A more likely

explanation would be that the basic modification

procedures other than mediation essays reduced

the frequency of target behaviors to a very small

number of hard-core miscreants who emitted

a disproportionate share of disruptive behaviors.

The successful use of mediation essays with this

latter group thus nearly eliminated the target

behaviors. Since the observers tallied total behaviors but not students, data to substantiate

this hypothesis are not available.

While target misbehaviors increased in frequency during Reversal, they did not increase

to Baseline levels. Misbehavior frequency during

Reversal was about one-third that of Baseline.

This suggests that during the conditions, other

variables were becoming effective in maintaining appropriate behaviors. It is possible that the

children were verbalizing the consequences to

themselves at this point. The aides were reluctant to eliminate all operant control during Reversal. Such comments as: "You really can't

expect me to give up what works!" and

"There'll be the same chaos as before if I do

this!" resulted in a decrease from the projected

10-day reversal period to five days to secure the

aides' cooperation. One might assume that the

aides continued to implement some modification

procedures during Reversal.

An important aspect of the present approach

is that the aides and children acted as experimenters and observers in jointly developing action research in the school setting (Hall et at.,

1971). Success was encountered in employing

elementary students as reliable observers. Since

most supervising adults find it difficult to spend

time observing and recording behaviors, the use

of student observers gave the aides more time

to study the data collected and develop treatment plans. The regrouping of observers during

Reversal and Post Check2 made no significant

difference in recording and reliability.

Of practical consideration to teachers and

school administrators is the fact that the study

was implemented without raising either material or personnel costs. The resources used were

intrinsic to the regular school environment

and were purchased with proceeds donated

from special student-council projects, classroom

cookie sales, and student hobby bazaars.

Research is needed to test the relative effectiveness of mediation techniques as compared

ELIMINATING DISRUPTIVE LUNCHROOM BEHAVIOR

297

with token economies in modifying classroom Herman, S. H. and Tramontana, J. Instructions

and group versus individual reinforcement in

behavior. In the event that they prove to be

modifying disruptive group behavior. Journal of

equally effective, mediation training would seem

Applied Behavior Analysis, 1971, 4, 113-119.

to be advantageous, considering time, effort, and Hinds, C. and Roehike, H. J. A. Learning theory

approach to group counseling with elementary

money.

REFERENCES

Bijou, S. W., Peterson, R. F., and Ault, M. H. A

method to integrate descriptive and experimental

field studies at the level of data and empirical

research. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,

1968, 1, 175-191.

Blackwood, R. 0. The operant conditioning of

verbally mediated self-control in the classroom.

Journal of School Psychology, 1970, 8, 251-258.

Blackwood, R. 0. The operant control of behavior.

Akron, Ohio: Exordium Press, 1971.

Blackwood, R. 0. Mediated self-control: an operant model of rational behavior. Akron, Ohio:

Exordium Press, 1972.

Botel, Morton. Botel's prediction research level: a

simple technique for eliminating readability level

of books. Chicago: Follett, 1962.

Broden, M., Hall, R. V., and Mitts, B. The effect

of self-recording on the classroom behavior of

two eighth-grade students. Journal of Applied

Behavior Analysis, 1971, 4, 191-199.

Hall, R. V., Fox, R., Willard, D., Goldsmith, L.,

Emerson, M., Owens, M., Davis, F., and Porcia,

E. The teacher as observer and experimenter

in modification of disputing and talking-out behaviors. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,

1971, 4, 141-149.

school children. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 1970, 17, 49-55.

Madsen, C. H., Becker, W. C., and Thomas, D. R.

Rules, praise and ignoring: elements of elementary classroom control. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 1968, 1, 139-150.

Miller, L. K. and Schneider, R. The use of a token

system in project Head Start. Journal of Applied

Behavior Analysis, 1970, 3, 213-220.

Sandler, I. M. Characteristics of women working

as child aides in a school-based prevention mental health program. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Rochester, 1970.

Schutte, R. C. and Hopkins, B. L. The effects of

teacher attention on following instructions in a

kindergarten class. Journal of Applied Behavior

Analysis, 1970, 3, 117-122.

Zeilberger, J., Sampen, S. E., and Sloane, H. N., Jr.

Modification of a child's problem behaviors in

the home with the mother as therapist. Journal

of Applied Behavior Analysis, 1968, 1, 47-53.

Zimmerman, E. and Zimmerman, J. The alteration

of behavior in a special classroom situation.

Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 1962, 5, 59-60.

Received 18 September 1972.

(Revision requested 4 December 1972.)

(Final acceptance 14 January 1973.)

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- Projective Tests PsychologyDocumento4 pagineProjective Tests PsychologytinkiNessuna valutazione finora

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (73)

- Master AslDocumento83 pagineMaster AslAm MbNessuna valutazione finora

- MBTIDocumento48 pagineMBTISamNessuna valutazione finora

- Slides M-I Emotional IntelligenceDocumento75 pagineSlides M-I Emotional IntelligenceDinesh SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- The 5 Attributes of Social Work As A Pro PDFDocumento3 pagineThe 5 Attributes of Social Work As A Pro PDFLaddan BabuNessuna valutazione finora

- TENSESDocumento34 pagineTENSESLalu FahrurroziNessuna valutazione finora

- Why Systemic Functional Linguistics Is The Theory of Choice For Students of LanguageDocumento12 pagineWhy Systemic Functional Linguistics Is The Theory of Choice For Students of LanguageFederico RojasNessuna valutazione finora

- English Grammar and Correct Usage Sample TestsDocumento2 pagineEnglish Grammar and Correct Usage Sample TestsOnin LaucsapNessuna valutazione finora

- Desra Miranda, 170203075, FTK-PBI, 085214089391Documento65 pagineDesra Miranda, 170203075, FTK-PBI, 085214089391Camille RoaquinNessuna valutazione finora

- A Procedure For Concurrently Measuring Elapsed Time and Response FrequencyDocumento2 pagineA Procedure For Concurrently Measuring Elapsed Time and Response FrequencyALEJANDRO MATUTENessuna valutazione finora

- Behavior in The Beginning AzrinDocumento2 pagineBehavior in The Beginning AzrinALEJANDRO MATUTENessuna valutazione finora

- 1990 Treatment of Tourette Syndrome by Habit Reversal A Waiting-List Control Group ComparisonDocumento14 pagine1990 Treatment of Tourette Syndrome by Habit Reversal A Waiting-List Control Group ComparisonALEJANDRO MATUTENessuna valutazione finora

- B. F. Skinner-The Last Few DaysDocumento2 pagineB. F. Skinner-The Last Few DaysALEJANDRO MATUTENessuna valutazione finora

- Behavior in The Beginning AzrinDocumento2 pagineBehavior in The Beginning AzrinALEJANDRO MATUTENessuna valutazione finora

- AZRIN Reinforcement and Instructions With Mental PatientsDocumento5 pagineAZRIN Reinforcement and Instructions With Mental PatientsALEJANDRO MATUTENessuna valutazione finora

- AZRIN Reinforcement and Instructions With Mental PatientsDocumento5 pagineAZRIN Reinforcement and Instructions With Mental PatientsALEJANDRO MATUTENessuna valutazione finora

- Job Finding AzrinDocumento9 pagineJob Finding AzrinALEJANDRO MATUTENessuna valutazione finora

- Ferster, Punishment of SΔ Responding in Matching to Sample bDocumento12 pagineFerster, Punishment of SΔ Responding in Matching to Sample bALEJANDRO MATUTENessuna valutazione finora

- SCHOENFELD Characteristics of Responding Under A TemporallyDocumento8 pagineSCHOENFELD Characteristics of Responding Under A TemporallyALEJANDRO MATUTENessuna valutazione finora

- The Shape of Some Wavelength Generalization GradientsDocumento10 pagineThe Shape of Some Wavelength Generalization GradientsALEJANDRO MATUTENessuna valutazione finora

- Sidman, M. (2002) - Notes From The Beginning of Time. The Behavior Analyst, 25, 3-13Documento11 pagineSidman, M. (2002) - Notes From The Beginning of Time. The Behavior Analyst, 25, 3-13ALEJANDRO MATUTENessuna valutazione finora

- Behavioral ContrastDocumento15 pagineBehavioral ContrastALEJANDRO MATUTENessuna valutazione finora

- Behavioral ContrastDocumento15 pagineBehavioral ContrastALEJANDRO MATUTENessuna valutazione finora

- Administrative Content - Journal Masthead, Notices, IndexesDocumento7 pagineAdministrative Content - Journal Masthead, Notices, IndexesALEJANDRO MATUTENessuna valutazione finora

- Schedules of Conditioned Reinforcement During Experimental ExtinctionDocumento5 pagineSchedules of Conditioned Reinforcement During Experimental ExtinctionALEJANDRO MATUTENessuna valutazione finora

- Amplitude-Induction Gradient of A Small Human Operant in An Escape-Avoidance SituationDocumento3 pagineAmplitude-Induction Gradient of A Small Human Operant in An Escape-Avoidance SituationALEJANDRO MATUTENessuna valutazione finora

- Avoidance Learning in Dogs Without A Warning StimulusDocumento7 pagineAvoidance Learning in Dogs Without A Warning StimulusALEJANDRO MATUTENessuna valutazione finora

- An Automatic Device For Dispensing Food Kept in A Liquid MediumDocumento3 pagineAn Automatic Device For Dispensing Food Kept in A Liquid MediumALEJANDRO MATUTENessuna valutazione finora

- A High-Power Noise Amplifier With An Electronic Keying SystemDocumento2 pagineA High-Power Noise Amplifier With An Electronic Keying SystemALEJANDRO MATUTENessuna valutazione finora

- Smoking Behavior Bya ConditioningDocumento8 pagineSmoking Behavior Bya ConditioningALEJANDRO MATUTENessuna valutazione finora

- Rapid Development of Multiple-Schedule Performances With Retarded ChildrenDocumento10 pagineRapid Development of Multiple-Schedule Performances With Retarded ChildrenALEJANDRO MATUTENessuna valutazione finora

- The Use of Response Priming To Improve PrescribedDocumento4 pagineThe Use of Response Priming To Improve PrescribedALEJANDRO MATUTENessuna valutazione finora

- Smoking Behavior Bya ConditioningDocumento8 pagineSmoking Behavior Bya ConditioningALEJANDRO MATUTENessuna valutazione finora

- Replication of The Achievement Place ModelDocumento13 pagineReplication of The Achievement Place ModelALEJANDRO MATUTENessuna valutazione finora

- The Behavior Observation InstrumentDocumento15 pagineThe Behavior Observation InstrumentALEJANDRO MATUTENessuna valutazione finora

- Vioral Two Appa Ra Toilet Training Retarded Children' BugleDocumento5 pagineVioral Two Appa Ra Toilet Training Retarded Children' BugleALEJANDRO MATUTENessuna valutazione finora

- Jaba Empirically SupportedDocumento6 pagineJaba Empirically SupportedALEJANDRO MATUTENessuna valutazione finora

- Jaba Biofeedback and Rational-Emotive Therapy 00104-0126Documento14 pagineJaba Biofeedback and Rational-Emotive Therapy 00104-0126ALEJANDRO MATUTENessuna valutazione finora

- Lep 2Documento6 pagineLep 2api-548306584Nessuna valutazione finora

- Bottom Up Lesson PlanDocumento40 pagineBottom Up Lesson PlanDeborahCordeiroNessuna valutazione finora

- Math Lesson Plan 4Documento4 pagineMath Lesson Plan 4api-299621535Nessuna valutazione finora

- Sociology of Organizations - InformationDocumento1 paginaSociology of Organizations - InformationObservatorio de Educación de UninorteNessuna valutazione finora

- Teaching Artificial Intelligence AI With AI For AIDocumento4 pagineTeaching Artificial Intelligence AI With AI For AIsmeet kadamNessuna valutazione finora

- Leadership AssignmentDocumento2 pagineLeadership AssignmentSundus HamidNessuna valutazione finora

- Group 3 Learning Report ItpDocumento75 pagineGroup 3 Learning Report ItpClarence AblazaNessuna valutazione finora

- Brand Character As A Function of Brand LDocumento7 pagineBrand Character As A Function of Brand LChamini NisansalaNessuna valutazione finora

- Arenas - Universal Design For Learning-1Documento41 pagineArenas - Universal Design For Learning-1Febie Gail Pungtod ArenasNessuna valutazione finora

- Lesson 1 Determine Trainees CharacteristicsDocumento3 pagineLesson 1 Determine Trainees CharacteristicsDcs JohnNessuna valutazione finora

- (B-2) Past Continuous TenseDocumento3 pagine(B-2) Past Continuous TenseDien IsnainiNessuna valutazione finora

- Semester Plan: (Dictation)Documento9 pagineSemester Plan: (Dictation)Future BookshopNessuna valutazione finora

- Extracted Pages From TSPSC AEE Syllabus 2017 - Ts Assistant Executive Engineer Exam PatternDocumento2 pagineExtracted Pages From TSPSC AEE Syllabus 2017 - Ts Assistant Executive Engineer Exam PatternAravind KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- American Headway 3 3rd Edition Student Book - Ershad - Eslahi-002Documento20 pagineAmerican Headway 3 3rd Edition Student Book - Ershad - Eslahi-002Ehsan Ashrafi100% (1)

- Paraphrase, Summary, and Precis - How To Write ThemDocumento3 pagineParaphrase, Summary, and Precis - How To Write ThemAkshat MehtaNessuna valutazione finora

- Cefr Grammar Levels - 1425642569 PDFDocumento6 pagineCefr Grammar Levels - 1425642569 PDFkhaledhnNessuna valutazione finora

- Expert Systems and AIDocumento17 pagineExpert Systems and AIPallavi PradhanNessuna valutazione finora

- Psychology ProjectDocumento17 paginePsychology ProjectMoyoandmamat OhiomobaNessuna valutazione finora

- ACCA f1 TrainingDocumento10 pagineACCA f1 TrainingCarlene Mohammed-BalirajNessuna valutazione finora

- Artificial Intelligence Assignment 5Documento9 pagineArtificial Intelligence Assignment 5natasha ashleeNessuna valutazione finora

- Preposition Excel UPSR BIDocumento11 paginePreposition Excel UPSR BIJinnie LiewNessuna valutazione finora