Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

Biografia Unui Om Politic

Caricato da

Claudiu-Mihai DumitrescuCopyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Biografia Unui Om Politic

Caricato da

Claudiu-Mihai DumitrescuCopyright:

Formati disponibili

Criticism of the EUs Economic Performance

The most obvious criticism to make of the economic performance of the EU is that simply put

it hasnot been that impressive. From 1957 to 1973, at which time the UK joined the EC, the

averageannual growth rates of Germany, France, the Netherlands, and Italy were all in excess

of 4.5 percent and the average annual growth rate of the Inner Six (the previous four countries

in addition toBelgium and Luxembourg) was 4.9 per cent. In contrast, the UK grew at an

average rate of 2.8 per cent over the same time period. However, this high growth in the EC

was largely a result ofreversing the destruction of the Second World War rather by virtue of

EC membership (this can beseen in the high growth rates of other war-damaged nations who

were not in the EC such asSwitzerland, Sweden, and Norway). Between 1980 and 2012 on the

other hand, the UK grew at anannual rate of 2 per cent and the Inner Six grew at an average

rate of 1.6 per cent. During this period the EUs share of global GDP consistently declined

and now stands at approximately 25 percent.A number of reasons have been suggested for the

EUs relatively anaemic economic record, the firstof which concerns its trade policy. As

previously mentioned, extra-EU trade is governed by the EU,not individual member states,

who impose a common external tariff on non-EU imports (in 2012the average rate was 5.5 per

cent but with enormous variety). It has been suggested that it is thisexternal tariff, and

subsequent reduction in extra-EU trade, that has caused growth opportunities to be missed by

economies in the EU. It has acted to restrict its members ability to trade with the restof the

world, whose impressive growth, stimulated initially by the GATT agreements andsubsequent

trade liberalisation and later by globalisation, has outpaced that of the EUs

73

.The centralisation and bureaucracy of the EU have also been said to dampen economic

growth. Asthe process of political and economic integration in the EU has accelerated, there

has been a paralleltrend regarding centralised decision-making that decisions are being

made increasingly far fromthe people they affect and that the EUs principle of subsidiarity,

the principle that wherever possible decision should be taken as close to affected citizens

as possible, is being paid lip serviceonly. While the creation of a customs union removes trade

barriers that can prevent thespecialisation of nation states, which Adam Smith identified as the

source of prosperity, this benefitis only applicable if open trade would not otherwise exist,

otherwise the benefits of greater size areless apparent. The optimal size of a nation can be

thought of as a trade-off between the harnessingeconomies of scale in the provision of public

goods and the increasing difficulty of governing anincreasingly heterogeneous community

that is not suited to a one-size-fits-all approach to policy

74

.Of the 10 wealthiest countries in the world, on a GDP (PPP) per capita basis, the single one

with asignificantly large population is the United States of America

75

, which benefits from a level ofdecentralisation not commonly found across the globe

76

. A further criticism levelled at some of theregulations and directives imposed on member

states by the EU is that they are wasteful orineffectual. One of the most debated EU

regulations, on the issue of whether or not it contributes tothe EUs relatively inflexible labour

markets, is the Working Time Directive (WTD), which coststhe UK 4.2 billion annually

77

, despite UK workers having the choice to opt-out of the 48-hourweek.Despite being one of

the most lauded achievements of the EU by pro-integrationists, theintroduction of the euro has

certainly not been an unqualified success. Critics of the currency unionargue that the

structurally divergent economies of the EU are not suited to the demands of a singlemonetary

union, especially in the absence of a corresponding fiscal union. Productivity

differences between the core and periphery economies of the Eurozone, exacerbated by higher

prices ineconomies such as Spain and Greece caused by the spending boom that access to the

lower ECBinterest rates stimulated, were reflected in a competitiveness gap between the two

which, in lieu of an exchange rate adjustment, resulted in large and growing current account

deficit in the economies of the latter. Additionally, peripheral economies found their access to

cheap financing greatly expanded after their ascension to the euro and so governments, banks,

and households all took on high levels of debt with disastrous consequences during the

sovereign debt crisis

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- Text 10 DemocratieDocumento8 pagineText 10 DemocratieDaniela SerbanicaNessuna valutazione finora

- Essay On Economic Impacts of Euromarkets and Other Offshore Markets On Global Financial MarketDocumento4 pagineEssay On Economic Impacts of Euromarkets and Other Offshore Markets On Global Financial MarketKimkhorn LongNessuna valutazione finora

- Name: Sidhant Nahta Warwick ID: 1005007 Class Teacher: Theodore Koutmeriedes Class Group: TK 3 Macroeconomics Essay I (Week 21)Documento4 pagineName: Sidhant Nahta Warwick ID: 1005007 Class Teacher: Theodore Koutmeriedes Class Group: TK 3 Macroeconomics Essay I (Week 21)Sidhant NahtaNessuna valutazione finora

- 264 293 ForumDocumento30 pagine264 293 ForumAnkur MittalNessuna valutazione finora

- ChKontaxi EconChallEnlargEUDocumento5 pagineChKontaxi EconChallEnlargEUChristina KontaxiNessuna valutazione finora

- AssignmentDocumento3 pagineAssignmentAngel Livia NataliaNessuna valutazione finora

- Europe Union and Trade PolicyDocumento38 pagineEurope Union and Trade PolicyCorina BanghioreNessuna valutazione finora

- Ifm-Group 9: Presenters Reshma Jayakumar Sisira Sivan Soosana Joy Sruthi Ramachandran Sruthi SrinivasanDocumento28 pagineIfm-Group 9: Presenters Reshma Jayakumar Sisira Sivan Soosana Joy Sruthi Ramachandran Sruthi SrinivasandoraemonNessuna valutazione finora

- Fostering Trade and Export Promotion in Overcoming The Global Economic CrisisDocumento19 pagineFostering Trade and Export Promotion in Overcoming The Global Economic CrisisShariq NeshatNessuna valutazione finora

- Contribution of The European Union in The World TradeDocumento20 pagineContribution of The European Union in The World TradeShreyasi BoseNessuna valutazione finora

- TAZA Study - Main VersionDocumento21 pagineTAZA Study - Main Versionjohn_miller3043Nessuna valutazione finora

- SourcesresearchDocumento15 pagineSourcesresearchapi-297147759Nessuna valutazione finora

- Edexcel As Econ Unit 2 FullDocumento198 pagineEdexcel As Econ Unit 2 Fullloca_sanamNessuna valutazione finora

- Essay 2 ChapterDocumento2 pagineEssay 2 Chapterronaldo mendozaNessuna valutazione finora

- Integration EssayDocumento7 pagineIntegration EssayCezar CorobleanNessuna valutazione finora

- GeographyDocumento9 pagineGeographyapi-354037574Nessuna valutazione finora

- Brexit: Economic ShockDocumento9 pagineBrexit: Economic ShockblahNessuna valutazione finora

- Il Metodo MontessoriDocumento31 pagineIl Metodo MontessoriLucaNessuna valutazione finora

- Fundamental Flaws in The European Project: George Irvin, Alex IzurietaDocumento3 pagineFundamental Flaws in The European Project: George Irvin, Alex IzurietaAkshay SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Greater Economic IntegrationDocumento13 pagineGreater Economic IntegrationMWhiteNessuna valutazione finora

- Op-Ed AS FT 230809Documento2 pagineOp-Ed AS FT 230809BruegelNessuna valutazione finora

- Research - Why EU Is Major Trading PartnerDocumento9 pagineResearch - Why EU Is Major Trading PartnerybguptaNessuna valutazione finora

- BrexitDocumento11 pagineBrexithuyNessuna valutazione finora

- 2 EU ExpansionDocumento2 pagine2 EU ExpansionMark MatyasNessuna valutazione finora

- SWOT Analysis of The European UnionDocumento12 pagineSWOT Analysis of The European UnionJoanna Diane Mortel100% (3)

- The Real Effects of European Monetary Union: Philip R. LaneDocumento20 pagineThe Real Effects of European Monetary Union: Philip R. LanedanielpupiNessuna valutazione finora

- We Are All Europeans NowDocumento3 pagineWe Are All Europeans NowAlexander MirtchevNessuna valutazione finora

- What Future For The EU After Brexit?: Paul de GrauweDocumento3 pagineWhat Future For The EU After Brexit?: Paul de Grauwewaleedrana786Nessuna valutazione finora

- Regional IntegrationDocumento3 pagineRegional IntegrationEdwinwangkeNessuna valutazione finora

- Iosif 329Documento15 pagineIosif 329kalexyzNessuna valutazione finora

- Expensive Living: The Greek Experience Under The Euro: Theodore Pelagidis and Taun ToayDocumento10 pagineExpensive Living: The Greek Experience Under The Euro: Theodore Pelagidis and Taun ToayThanos DrakidisNessuna valutazione finora

- Economic Crisis Paper en LRDocumento16 pagineEconomic Crisis Paper en LRPranav DwivediNessuna valutazione finora

- Eurozone Crisis ThesisDocumento8 pagineEurozone Crisis Thesisfjf8xxz4100% (2)

- Regional Economic Integration: Benefits and ChallengesDocumento39 pagineRegional Economic Integration: Benefits and ChallengesBikash Sahu100% (1)

- The European Union As A Model For Regional IntegrationDocumento8 pagineThe European Union As A Model For Regional Integrationpatilgeeta4Nessuna valutazione finora

- International Financial ManagementDocumento47 pagineInternational Financial ManagementAshish PriyadarshiNessuna valutazione finora

- Assignment Final - 2Documento6 pagineAssignment Final - 2knavstragetyNessuna valutazione finora

- Gazdasági Nyelvvizsga TételekDocumento5 pagineGazdasági Nyelvvizsga TételekHallo HaloNessuna valutazione finora

- Economic IntegrationDocumento3 pagineEconomic Integrationatta_tahirNessuna valutazione finora

- Reasons Why The Eurozone Went Into RecessionDocumento1 paginaReasons Why The Eurozone Went Into Recessionmp11abiNessuna valutazione finora

- Economics ProjectDocumento2 pagineEconomics ProjectRohan KunduNessuna valutazione finora

- Running Head: International FinanceDocumento12 pagineRunning Head: International FinanceCarlos AlphonceNessuna valutazione finora

- Chap 008Documento56 pagineChap 008saherhcc4686Nessuna valutazione finora

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Adopting A Single Currency EuroDocumento6 pagineAdvantages and Disadvantages of Adopting A Single Currency EuroEdward XavierNessuna valutazione finora

- United States, European Union, Economic Integration and Foreign PolicyDocumento7 pagineUnited States, European Union, Economic Integration and Foreign Policywilma putriNessuna valutazione finora

- Week 7 - Lecture 6 - UK and The EUDocumento8 pagineWeek 7 - Lecture 6 - UK and The EUKunal SharmaNessuna valutazione finora

- Revista SocialistaDocumento38 pagineRevista SocialistaMiguel Ángel Puerto FernándezNessuna valutazione finora

- The European Union - Politics and PoliciesDocumento14 pagineThe European Union - Politics and Policieskarolina villero peñaNessuna valutazione finora

- Crises in The Euro Area and Challenges For The European Union's Democratic LegitimacyDocumento6 pagineCrises in The Euro Area and Challenges For The European Union's Democratic LegitimacyGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNessuna valutazione finora

- British Trade UnionsDocumento15 pagineBritish Trade UnionsHemant MeenaNessuna valutazione finora

- Estimating The Effects of Brexit On UKDocumento5 pagineEstimating The Effects of Brexit On UKAstha AhujaNessuna valutazione finora

- The Hub and Spoke Approach of European Trade PolicyDocumento2 pagineThe Hub and Spoke Approach of European Trade PolicyspamtdebNessuna valutazione finora

- The Potential Benefits and Costs of Adopting The Euro For United KingdomDocumento4 pagineThe Potential Benefits and Costs of Adopting The Euro For United Kingdomnikunjgoyal1234Nessuna valutazione finora

- 1 The European UnionDocumento7 pagine1 The European UnionMark MatyasNessuna valutazione finora

- A Programme of Social and National Rescue for GreeceDocumento48 pagineA Programme of Social and National Rescue for GreeceUlises NoyolaNessuna valutazione finora

- Brexit Analysis IIDocumento7 pagineBrexit Analysis IIPhine TanayNessuna valutazione finora

- Quarterly Report On The Euro Area: Highlights in This IssueDocumento52 pagineQuarterly Report On The Euro Area: Highlights in This IssueIrene PapponeNessuna valutazione finora

- From Convergence to Crisis: Labor Markets and the Instability of the EuroDa EverandFrom Convergence to Crisis: Labor Markets and the Instability of the EuroNessuna valutazione finora

- The Reform of Europe: A Political Guide to the FutureDa EverandThe Reform of Europe: A Political Guide to the FutureValutazione: 2 su 5 stelle2/5 (1)

- State Exam Questions +Documento29 pagineState Exam Questions +Alok KumarNessuna valutazione finora

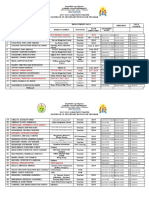

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocumento2 pagineCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsNessuna valutazione finora

- nOTes Int RelDocumento12 paginenOTes Int RelDua BalochNessuna valutazione finora

- Newcombe 2003Documento9 pagineNewcombe 2003Nicolae VedovelliNessuna valutazione finora

- Construction of Media MessagesDocumento16 pagineConstruction of Media MessagesBakirharunNessuna valutazione finora

- Osmeña vs. Pendatun (Digest)Documento1 paginaOsmeña vs. Pendatun (Digest)Precious100% (2)

- SriLankaUnites Is A MisnomerDocumento4 pagineSriLankaUnites Is A MisnomerPuni SelvaNessuna valutazione finora

- Philhealth Circular 2022 - 0014 - Full Financial Risk Protection For Filipino Health Workers InfectedDocumento8 paginePhilhealth Circular 2022 - 0014 - Full Financial Risk Protection For Filipino Health Workers InfectedNanievanNessuna valutazione finora

- How To Draft A MemorialDocumento21 pagineHow To Draft A MemorialSahil SalaarNessuna valutazione finora

- CaseDocumento22 pagineCaseLex AcadsNessuna valutazione finora

- An Introduction To Roman Dutch LawDocumento556 pagineAn Introduction To Roman Dutch LawSimu JemwaNessuna valutazione finora

- Church History II - Lesson HandoutsDocumento594 pagineChurch History II - Lesson HandoutsFrancisco Javier Beltran Aceves100% (1)

- Taxation NotesDocumento27 pagineTaxation NotesRound RoundNessuna valutazione finora

- Postal Id Application FormDocumento2 paginePostal Id Application FormDewm Dewm100% (2)

- JFQ 72Documento112 pagineJFQ 72Allen Bundy100% (1)

- 6Documento22 pagine6Stephanie BarreraNessuna valutazione finora

- Email Address First Name Email AddressDocumento103 pagineEmail Address First Name Email AddressIMRAN KHAN50% (2)

- Lesson 1Documento2 pagineLesson 1Kimberley Sicat BautistaNessuna valutazione finora

- Manila Standard Today - May 30, 2012 IssueDocumento16 pagineManila Standard Today - May 30, 2012 IssueManila Standard TodayNessuna valutazione finora

- Metropolitan Bank and Trust Company, Inc v. NWPCDocumento2 pagineMetropolitan Bank and Trust Company, Inc v. NWPCCedricNessuna valutazione finora

- DefendingLife2008 StrategiesForAProLifeAmericaDocumento865 pagineDefendingLife2008 StrategiesForAProLifeAmericaLaurianNessuna valutazione finora

- History Essay WW2 DraftDocumento4 pagineHistory Essay WW2 DraftbobNessuna valutazione finora

- ATF Response ATF O 5370 Federal Firearms Administrative Action Policy and Procedures 1D - RedactedDocumento11 pagineATF Response ATF O 5370 Federal Firearms Administrative Action Policy and Procedures 1D - RedactedAmmoLand Shooting Sports News100% (1)

- Archipelagic DoctrineDocumento4 pagineArchipelagic DoctrineMalolosFire Bulacan100% (4)

- F2867889-67A7-4BA9-9F41-8B9C11F1D730 (2)Documento1 paginaF2867889-67A7-4BA9-9F41-8B9C11F1D730 (2)Felipe AmorosoNessuna valutazione finora

- El Filibusterismo SynopsisDocumento2 pagineEl Filibusterismo SynopsisMelissa Fatima Laurente DosdosNessuna valutazione finora

- Class 8th Winter Holiday Homework 2021-22Documento5 pagineClass 8th Winter Holiday Homework 2021-22Ishani Ujjwal BhatiaNessuna valutazione finora

- 2017-2018 GRADUATE TRACER Bachelor of Secondary Education ProgramDocumento6 pagine2017-2018 GRADUATE TRACER Bachelor of Secondary Education ProgramCharlie MerialesNessuna valutazione finora

- The Degar-Vietnam Indigenous GroupDocumento3 pagineThe Degar-Vietnam Indigenous GroupBudaiNessuna valutazione finora

- 15 VISION (E) PRELIMS Test 2022Documento58 pagine15 VISION (E) PRELIMS Test 2022ravindranath vijayNessuna valutazione finora