Documenti di Didattica

Documenti di Professioni

Documenti di Cultura

JIndianSocPedodPrevDent30294-1556553 041925

Caricato da

NiNis Khoirun NisaTitolo originale

Copyright

Formati disponibili

Condividi questo documento

Condividi o incorpora il documento

Hai trovato utile questo documento?

Questo contenuto è inappropriato?

Segnala questo documentoCopyright:

Formati disponibili

JIndianSocPedodPrevDent30294-1556553 041925

Caricato da

NiNis Khoirun NisaCopyright:

Formati disponibili

[Downloadedfreefromhttp://www.jisppd.comonWednesday,October24,2012,IP:110.138.184.

158]||ClickheretodownloadfreeAndroidapplicationforthisjour

Review Article

Radix entomolaris and paramolaris in children:

A review of the literature

Nagaveni NB, Umashankara KV1

Abstract

Pediatric dentistry in the current scenario is not just about

teeth and gums that are easily visible in childrens mouth

anymore. It is all about those structures that are hidden,

difficult to identify, and often remain undiagnosed. Dentist

can come across various anomalies pertaining to the crown

structure during the clinical practice. Although supernumerary

tooth is the most commonly seen anomaly, the presence of

extra roots in molars is an interesting example of anatomic

root variation. It is well known that both primary and

permanent mandibular first molars usually have roots, one

mesial, and the other distal root. Very rarely an additional

third root (supernumerary root) is seen and when it is located

distolingually to the main distal root is called radix entomolaris

(RE) and when it is placed mesiobuccaly to the mesial root

is called radix paramolaris (RP). The purpose of this article

is to discuss the prevalence, morphology, classification,

clinical diagnosis, and significance of supernumerary roots

in contemporary clinical pediatric dentistry.

Key words

Distolingual root, endodontic treatment, extra third root,

periapical radiographs, radix entomolaris, radix paramolaris

Department of Pediatric and Preventive Dentistry, College of

Dental Sciences, 1Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery,

Bapuji Dental College and Hospital, Davangere, Karnataka,

India.

Correspondence:

Dr. N. B. Nagaveni, Department of Pediatric and Preventive

Dentistry, College of Dental Sciences, Davangere, Karnataka,

India. E-mail: nagavenianurag@gmail.com

Access this article online

Quick Response Code:

Website:

www.jisppd.com

DOI:

10.4103/0970-4388.99978

PMID:

***

overall benefit to a child patient because when they are

present are highly challenging to diagnosis as well as

to endodontic treatment. The purpose of this article

is to discuss the prevalence, morphology, classification,

clinical diagnosis, and significance of supernumerary

roots in contemporary clinical pediatric dentistry.

Introduction

Review of the Literature

Molars are frequently affected by caries at an early

age and may require successful endodontic treatment

for their long-term retention in the oral cavity. The

objective of pediatric endodontic therapy is thorough

removal of the pulp tissue from all the roots and canals

followed by chemo-mechanical cleaning and filling

with a suitable material. Failure to diagnose and treat

the extra roots in molars may lead to the endodontic

treatment failure and even tooth loss at an early age

resulting patient to suffer functionally, esthetically, and

psychologically. Therefore, pediatric dentist must be

aware of these unusual root structures to provide the

Synonyms

94

Radix entomolaris (RE) an additional third root was

first mentioned in the literature by Carabelli[1] in 1844

and is described by various terms, such as extra third

root or distolingual root or extra distolingual root.[2]

Radix paramolaris (RP) is known as the mesiobuccal

root[3] was first described by Bolk[4] in 1915.

Prevalence of RE and RP

Various prevalence studies have been done using

periapical radiographs,[5-9] extracted teeth[10-14] recently

by microcomputed tomography (micro-CT),[15-17] and

JOURNAL OF INDIAN SOCIETY OF PEDODONTICS AND PREVENTIVE DENTISTRY | Apr - Jun 2012 | Issue 2 | Vol 30 |

[Downloadedfreefromhttp://www.jisppd.comonWednesday,October24,2012,IP:110.138.184.158]||ClickheretodownloadfreeAndroidapplicationforthisjou

Nagaveni, et al.: Supernumerary roots in mandibular molars

cone-beam computed tomographic images (CBCT)

[Table 1]. [18-21] Therefore, interstudy variations

can be seen among different surveys. In periapical

radiographic method it is not easy to identify the extra

root, as superimposition of two roots occur resulting

inaccurate diagnosis. In the case of extracted teeth,

teeth might fracture during the extraction procedure as

they are more slender and curved. From studies based

on extracted teeth,[10-14] it was impossible to compare

precisely the prevalence related to gender and bilateral

occurrence of three-rooted permanent first molars. It

has been speculated that recent studies using advanced

techniques showed higher prevalence compared to

previous 2D image studies;[15-20] the reason could be

attributed to the use of 3D image analysis, which

provides more accurate determination.

Ethnic differences in permanent molars

The existence of RE/RP in permanent mandibular first

molar is associated with certain ethnic and racial groups.

The dentist therefore must be aware of racial anatomic

variations when diagnosing and managing endodontic

patients because he/she may see patients of diverse

ethnicities daily. Tu et al.[5] found a prevalence of 21.1%

using periapical radiographs and 33.33% using the conebeam computed tomography in Taiwanese subjects.[18]

Compared with the prevalence of the permanent threerooted mandibular molars in Taiwanese individuals,

33.33% data of the prevalence in the Tu et al.[18] study

are higher than those 2D image study by Tu et al.[5] By

using extracted teeth, Walker and Quackenbush[22] found

a prevalence of 14.6% in Hong Kong Chinese and Loh[10]

found a prevalence of 7.9% in Singapore Chinese subjects.

A maximum frequency of 3% is documented in the African

population[23] while in Eurosian and Indian populations

the frequency is less than 5%.[14] In Mangoloid traits

such as Eskimo, Chinese, and American Indians, it has

been reported that RE seen with a frequency ranging

from 530%.[14,22-27] Because of its high prevalence in

these populations, the RE is considered to be a normal

morphological variant (Eumorphic root morphology).

In Caucasians low frequency of 3.44.2% has been

found and considered to be unusual or dysmorphic root

morphology[9,28] [Table 1].

Prevalence of three roots in primary molars

Most previous surveys into the occurrence of an

extra root investigated extracted teeth, and hence

considered mainly permanent molars and virtually no

primary molars.[10-14] Analyzing the root configuration

in primary molars can be difficult because of the

presence of physiologic or pathologic root resorption,

and extracting primary molars with sound roots is

difficult because of root divergence. Therefore, fewer

studies have investigated the incidence of third roots

in the primary molars.

The prevalence of root variations is lower in the

primary dentition than in the permanent dentition.

There are several case reports[29,30] on the existence of

three-rooted primary mandibular molars but studies

of the prevalence of extra roots are few in number.

Tratman[14] reported that three-rooted mandibular first

molars are rare with a frequency of <1% in the primary

dentition and common in the permanent dentition.

Curzon and Curzon[31] suggested that the incidence of

primary anomalies is higher in Native American than

white populations. 21.1% of Taiwanese (Chinese) have

permanent three-rooted mandibular molars, but there is

little information on primary three-rooted mandibular

molars in those of Mongolian descent.[5] Jorgensen[32]

reported seven cases (0.67%) of an additional root in 1041

second primary molars extracted from Danish subjects.

Tratman[14] found no extra root in samples collected

from Europe and India, but found an additional root in

3 of 42 second primary molars (7.1%) from Japanese

subjects. A Japanese radiographic study revealed that

5.6% of 1408 samples of mandibular primary first

molars had an additional distolingual root.[33] In a study

by Tu et al.[34] the prevalence of supernumerary root

in primary first molars of Taiwanese children was 5%.

Recently Song et al.[35] found a maximum prevalence

of 27.8% and 9.7% of second primary and first primary

molars respectively in Korean children and Liu et al.[36]

reported 18 (9%) cases of three-rooted primary second

molars in Chinese subjects [Table 1].

Although extra root can be found in both first and

second molars of the primary dentition, there is

no definitive proven study showing whether the

presence of RE in primary molars, indicates extra

root in permanent molars, although the commonly

hypothesized field of development influence suggests

that this is the case. A long-term prospective study

involving the primary and permanent molars certainly

would add to the present knowledge. However,

recently Song et al.[35] assessed the incidence and

relationship of an additional root in the mandibular

first permanent molar and primary molars in 4050

children examined. They found additional roots in

33.1%, 27.8%, and 9.7% of the first permanent, second

primary, and first primary molars, respectively, and

concluded that when an additional root was present

in a primary molar, the probability of the posterior

JOURNAL OF INDIAN SOCIETY OF PEDODONTICS AND PREVENTIVE DENTISTRY | Apr - Jun 2012 | Issue 2 | Vol 30 |

95

[Downloadedfreefromhttp://www.jisppd.comonWednesday,October24,2012,IP:110.138.184.158]||ClickheretodownloadfreeAndroidapplicationforthisjour

Nagaveni, et al.: Supernumerary roots in mandibular molars

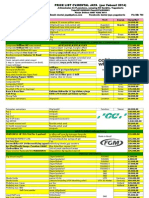

Table 1: Survey of available studies showing prevalence of

3-rooted mandibular first molar

Table 1: cond...

Author/Year

Population group

Author/Year

Population group Incidence (%)

Taylor (1899)[54]

Bolk (1915)[4]

Campbell (1925)[55]

United Kingdom

Netherlands

Australian

Aborigine

South African

Bushman

African Bantu

Chinese

Malay

Javanese

Indians

Eurasians

Japanese

Malay

Greenland Eskimo

Danish

Canadian Indians

European

Japanese

Caucasian

Aleut Eskimo

American Indian

Keewatin Eskimo

United Kingdom

Baffin Eskimo

Guam

Japanese

Chinese

Malaysian

Thai

Hong Kong Chinese

Hong Kong Chinese

Japanese

Chinese

(Singapore)

Saudi

Egyptian

Japanese

Negroid

Caucasian

Chinese

Senegalese

Hispanic children

Burmese

Thai

Taiwanese

Korean

Primary molars

(first and second)

Permanent first

molars

Germanese

Taiwanese

Liu et al. (2010)[36]

Garg et al. (2010)[51]

Song et al. (2010)[21]

Yang et al. (2010)[62]

Peiris et al. (2007)[63]

Huang et al. (2010)[64]

Chinese

Indian

Korean

Shanghai Chinese

Sri Lankan

Taiwanese

Drennan (1929)[56]

Shaw (1931)[57]

Tratman (1938)[14]

Laband (1941)[13]

Pedersen (1949)[24]

Jorgensen (1956)[32]

Somogyi-Csizmazia and Simons (1971)[38]

de Souza-Freitas et al. (1971)[37]

Skidmore and Bjorndahl (1971)[58]

Turner (1971)[25]

Curzon and Curzon (1971)[26]

Curzon (1973)[28]

Curzon (1974)[42]

Hochtstetter (1975)[12]

Sugiyama et al. (1976)[33]

Jones (1980)[11]

Reichart and Metah (1981)[27]

Walker and Quackenbush (1985)[22]

Walker (1988)[59]

Harada et al. (1989)[52]

Loh (1990)[10]

Younes et al. (1990)[60]

Ferraz and Pecora (1992)[9]

Yew and Chan (1993)[8]

Sperber and Moreau (1998)[23]

Steelman (1998)[39]

Gulabivala et al. (2001)[7]

Gulabivala et al. (2002)[6]

Tu et al. (2007)[5]

Song et al. (2009)[35]

Schafer et al. (2009)[61]

Tu et al. (2010)[34]

3.4

1

0

0

0

5.8

8.6

10.9

0.2

4.2

1.2

8.2

12.5

0.67

16

3.2

17.8

2.2

32

5.8

27

3.4

21.7

13

5.6

13.4

16

19

14.6

15

18.8

7.9

2.92

0.01

11.4

2.8

4.2

21.5

3

3.2

10.1

13

21.09

9.7, 27.8

9

5.97

24.5

32.35

3

22

adjacent molar also having an additional root was

greater than 94.3%.

Gender differences

Gender predilection for an additional root in the

first permanent molar has been reported by several

investigators. Some claimed it to be a sex-linked,

dominant character and others reported that it has

no sex predilection. Most studies have found male

predominance.[36-39] However, others reported that the

prevalence of extra root was similar in both sexes[10,34,36]

or rather more in females.[5] Tratman[14] mentioned

that it is more common on the right for the male and

bilateral for the female. Loh[10] did not show statistically

significant difference in predilection of RE for either

sex. Based on these reports, it is not common for RE

to occur symmetrically.

Topological predilection

The incidence of supernumerary roots in the first

permanent molar on the left and right side are variable

as seen from the reported studies.[14] Many studies

have found right-side predominance not only for the

permanent molar, but also for the primary molars.[5,14,39]

In contrast, some investigators reported a predilection

for the left side.[10]

Unilateral or bilateral occurrence of an additional

root is also a controversial issue. Some studies

reported bilateral occurrence of the RE ranging from

5067%.[5,10,36,39] According to Quackenbusch[40] and

other reports, this extra root occurred unilaterally in

approximately 40% of all cases and predominantly on

the right side. This is noticed in other reports also.[5,14,39]

This finding highly emphasized the fact that in treating

most right mandibular molars clinician always look for

additional distal root to prevent root canal treatment

failure.

33.1

1.35

5

Table 1: cond...

96

Incidence (%)

Prevalence of RE/RP in other Teeth

RE has been reported occurring in the first (7.4%),

second (0%), and third mandibular permanent molars

JOURNAL OF INDIAN SOCIETY OF PEDODONTICS AND PREVENTIVE DENTISTRY | Apr - Jun 2012 | Issue 2 | Vol 30 |

[Downloadedfreefromhttp://www.jisppd.comonWednesday,October24,2012,IP:110.138.184.158]||ClickheretodownloadfreeAndroidapplicationforthisjour

Nagaveni, et al.: Supernumerary roots in mandibular molars

(3.7%) occurring with a least frequency or none on the

second molar.[41]

The existence of RP root variant is very rare and occurs

less frequently than the RE. It seems to be rare in Europian

and Mongolian populations.[41] Visser[41] found 0%

(0/1954) for the mandibular first molar, 0.5% (11/2086)

for the second and 2% (28/1405) for the third molar.

Etiology

The exact etiology behind the development of RE/

RP is still unknown. The literature suggests that,

in dysmorphic, extra roots, its formation could be

related to external factors during odontogenesis,

or to penetrance of an atavistic gene or polygenetic

system whereas in eumorphic roots, racial genetic

factors cause more profound expression of a particular

gene that results in the more pronounced phenotypic

manifestation.[27] The high degree of RE in Mongoloid

populations has provoked more specific analyses of

the heritable basis of this supernumerary radicular

structure by various authors.[14,36,37] More specifically,

only Curzon[42] suggested that certain traits such as

the three-rooted molar had a high degree of genetic

penetrance as its dominance was reflected in the fact

that pure Eskimo and Eskimo/Caucasian mixes had

similar prevalence of the trait.

Morphology of RE and RP

The identification and external morphology of RE

and RP root complexes are described by Carlsen and

Alexandersen.[3,43] RE is found distolingually with its

coronal third completely or partially fixed to the distal

root. It usually appears smaller and more curved than

the distobuccal or mesial root and is located in the same

transverse plane as the two other roots.[Figure 1] This

Figure 1: Morphology of RE from different aspects (arrows)

suggests that dentists must pay special attention when

considering root canal treatment and/or extraction

for a molar with RE. The dimension of RE can vary

from a short conical extension to a mature root with

normal length and root canal [Figure 2].[2,43] It is crosssectionally more circular than the distal root, projected

lingually about 45 to the long axis of the tooth, and

has the type I canal system.[2,43] In most cases, the pulpal

extension is radiographically visible. In the apical two

thirds of the RE, a moderate to severe mesially or

distally oriented inclination can be seen in addition to

this inclination the root can be found straight or curved

to the lingual. Tratman[14] stated that RE is not simply

a division of the distal root but rather is a true extra

root with a separate orifice and apex.

RP is seen buccally to the mesial root and may be found

separate or fused with the mesial root.[Figure 3] The

dimensions of the RP can vary from a mature root

with a root canal, to a short conical extension.[3] This

additional root exists in two forms as separate and

nonseparate.[3]

Classification of RE and RP

RE a distolingual root exhibit diverse morphologic

features varying from severe curvature [2] to an

underdeveloped conical form.[21] De Moore et al.[2]

classified RE based on the curvature of the root or

root canal in bucco-lingual orientation (separate RE)

evaluated from 18 extracted human teeth into three

types [Table 2]. In 1991, Carlson and Alexandersen[43]

classified four types of RE (A, B, C, and AC), based on

the location of the cervical portion of the root and this

helps in identification of separate and non separate RE

[Table 3]. Recently in 2010 Song et al.[21] have suggested

a new classification based on morphologic characteristics

Figure 2: Radix entomolaris in permanent right first molar (arrow)

JOURNAL OF INDIAN SOCIETY OF PEDODONTICS AND PREVENTIVE DENTISTRY | Apr - Jun 2012 | Issue 2 | Vol 30 |

97

[Downloadedfreefromhttp://www.jisppd.comonWednesday,October24,2012,IP:110.138.184.158]||ClickheretodownloadfreeAndroidapplicationforthisjour

Nagaveni, et al.: Supernumerary roots in mandibular molars

Figure 3: Radix paramolaris in permanent right first molar (arrow)

Table 2: Classification of RE, based on its curvature[2]

Types Description

I

II

III

A straight root and canal

Initial entrance is curved but the root is straight

The coronal third of the root canal is curved; in addition, there is a

second, buccally oriented curve from the middle to the apical third.

Table 3: Classification of RE, based on the location of its

cervical portion[43]

Types Description

A

B

C

AC

Located distally, with two normal distal root components

Located distally, with one normal distal root component

A mesially located cervical part

A central location, between the distal and mesial root components

Table 4: New classification of RE[21]

Types

Features

Type I

Type II

No curvature

Curvature in the coronal third and straight continuation to the

apex

Type III

Curvature in the coronal third and additional buccal curvature

from the middle third to the apical third of the root.

Small type Root length less than half that of the distobuccal root.

Conical type Cone-shaped extension with no root canal

Table 5: Classification of RP[3]

Types Features

A

Refers to an RP in which the cervical part is located on the mesial root

complex

Refers to an RP in which the cervical part is located centrally, between

the mesial and distal root complexes.

assessed from cross-sectional computed tomography

technique [Table 4].

Carlsen and Alexandersen[3] classified RP into two

types by examining 203 permanent mandibular molars

with root complexes containing RP [Table 5].

98

Figure 4: Evidence of RE (c) and RP (d) in radiographs taken with

angulation. They are not evident on conventional radiographs

(a and b)

RE in Association with Other Anomalies

Some reports[23,44] showed that RE in the first molars

occurred in association with additional cusp usually

on the buccal side (protostylid). Therefore, it has been

suggested that extra root is nearly always associated

with an increased number of cusps and with an

increased number of root canals.[44] However, an

increased number of cusps are not necessarily related

to increased number of roots. George etal.[45] reported

simultaneous occurrence of shovel-shaped incisors,

three-rooted primary and permanent molars, talon

cusp and supernumerary tooth in a 7-year-old Hispanic

male patient. Whereas, Winkler and Ahmad[46] reported

multiroot anomalies including bifurcated maxillary

primary canine, primary three-rooted first molar and

bilateral primary three-rooted first and second primary

molars in Native Americans.

Examination of RE/RP

Clinical diagnosis

The crown and the two normal roots of a molar with a

distolingual/mesiobuccal root are very similar to those

found in a normal molar.[44] Hence, identification of RE/

RP is not really possible from only a clinical examination

of the crown. The literature has reported that clinical

observation and analysis of the cervical morphology

of the roots by means of periodontal probing facilitate

identification of RE. It has also been reported that the

presence of an extra cusp (tuberculum paramolare) or

more prominent occlusal distal or distolingual lobe, in

JOURNAL OF INDIAN SOCIETY OF PEDODONTICS AND PREVENTIVE DENTISTRY | Apr - Jun 2012 | Issue 2 | Vol 30 |

[Downloadedfreefromhttp://www.jisppd.comonWednesday,October24,2012,IP:110.138.184.158]||ClickheretodownloadfreeAndroidapplicationforthisjourn

Nagaveni, et al.: Supernumerary roots in mandibular molars

combination with a cervical prominence or convexity,

can indicate the presence of an additional root.[44] If

an RE or RP is diagnosed before endodontic treatment,

one knows what to expect or where to look once the

pulp chamber has been opened.

periodontal implications of extra roots in permanent

mandibular first molars.[44-46,48,49] The same caution

should be followed in the treatment of primary

mandibular molars with accessory roots as permanent

mandibular molars.

There are various methods to locate the orifice of

the extra roots. They can be listed as knowledge of

law of symmetry and law of orifice location, tactile

sensation with hand instruments, using various

instruments like endodontic explorer, path finder,

DG 16 probe and microopener, use of fiber-optic

illumination dental endoscopy, intraoral camera,

using surgical loupes, using operating microscope,

microcomputed tomography, and magnetic resonance

microscopy.[44]

Endodontic implications

Radiographic diagnosis

Anatomical variations of roots in the mandibular first

molar may be identified by reading radiographs carefully.

An accurate diagnosis of RE/RP is very important to

avoid complications or missing of canal during RCT. As

the RE/RP is mostly located in the same bucco-lingual

plane as the other two roots, a superimposition of both

roots can appear on the preoperative radiograph and

remain undiagnosed.[2,3,44] A thorough examination

of the preoperative radiograph and interpretation of

particular marks or characteristics, such as an unclear

view or outline of the distal/mesial root contour

or the root canal, can suggests the presence of a

hidden RE/RP.[44] Ingle et al.[47] has recommended

a thorough radiographic study of the involved tooth,

using exposure from the standard buccal-to-lingual

projection, one taken 20 from the mesial, and the third

taken 20 from the distal to obtain basic information

regarding the anatomy of the tooth. [Figure 4] Loh[10]

has claimed that the RE/RP does not normally appear in

periapical radiographs that are taken in the traditional

manner. Adjusting the exposure time and dose of

the x-ray and angulating the main beam (to avoid

superimposing the larger distobuccal/mesial root) can

to help make RE/RP more evident although accurate

interpretation of radiographs depends on the trained

eye.[10] A 1985 study by Walker and Quackenbush[22]

claimed that panoramic radiographs resulted in an

accuracy rate of approximately 90%.

Significance of RE/RP in clinical pediatric

dentistry

Apart from its role as a genetic marker, RE/RP has

significance in clinical pediatric dentistry. Many

studies have discussed the endodontic, exodontic, and

Root canal treatment should result in the thorough

mechanical and chemical debridement of the entire pulp

cavity, followed by complete obturation with a hermetic

seal. As a result, RE/RP pose a great endodontic

challenge, as incomplete pulp extirpation due to missed

canal can result in treatment failure. Dentists should be

familiar with multiple root anatomy to avoid missing

canals.

With RE, the conventional triangular access cavity

opening must be modified to take the form of a trapezoid

or rectangular form to better locate and access the

distolingual orifice of the additional root.[2,44] A severe

root inclination or canal curvature, particularly in the

apical third of the root (in type III RE), can cause shaping

aberrations such as straightening of the root canal or a

ledge that displays a loss of working length in the ledge

canal. Calberson et al.[44] recommend using flexible nickel

titanium rotary files to increase the chance of centering

the canal third and orifice relocation. Nevertheless,

unexpected complications (such as instrument separation)

occur and are more likely to happen in the RE due to the

severe curvature or narrow root canals. Therefore, after

relocation and enlargement of the orifice of the RE,

Calberson et al.[44] suggested initial root canal exploration

with small files (size 10 or less), determining the working

length of the curved root, and creating a glide path before

preparation to avoid procedural errors.

It also has been reported that regardless of the type

of root canal, the orifice of the RE can be located

distolingually from the root canals in the main distal root.

In 2009, Tu et al.[18] did a prevalence study in Taiwanese

subjects using cone-beam computed tomography and

estimated the interorifice distance of all canals in

mandibulat first molar with RE. The mean interorifice

distances from the distolingual canal to the distobuccal

(DB), mesiobuccal (MB), and mesiolingual (ML) canals

of the permanent three-rooted molars were 2.7, 4.4, and

3.5 mm, respectively. These values might help dentists

to locate orifices and to achieve successful endodontic

treatments of permanent molars with distolingual root.

In the case of RP, the access cavity must be extended in

mesiobuccal direction that involves modification in access

JOURNAL OF INDIAN SOCIETY OF PEDODONTICS AND PREVENTIVE DENTISTRY | Apr - Jun 2012 | Issue 2 | Vol 30 |

99

[Downloadedfreefromhttp://www.jisppd.comonWednesday,October24,2012,IP:110.138.184.158]||ClickheretodownloadfreeAndroidapplicationforthisjour

Nagaveni, et al.: Supernumerary roots in mandibular molars

cavity from triangular to rectangular or trapezoidal form

in order to better locate and access the canal of this root.

[3,44]

The same precautions and procedure should be

followed as in RE during endodontic procedure.

Exodontic procedure

During extraction of primary molars with three roots,

the clinician should make sure that the crown of the

premolar is not trapped in the inter-radicular area

of the primary molar as this could cause accidental

removal of the developing permanent tooth bud.[46]

After the extraction, dentist should examine the

extracted anomalous primary molar to confirm that

all roots have been retrieved.

Extraction of permanent first molar with RE is difficult

compared to the molar without RE. If rotational

movements are used, root fractures could occur. It is

expected that an extra distolingual root would fracture

during extraction due to its divergent and curved form.[2]

The low incidence of distolingual roots documented

previously is probably because the roots curvature was

in the line of extraction movements and withdrawal.[10]

A 2004 study[50] suggested that molars are extracted

more frequently than anteriors and premolars among

some races because those groups have a higher prevalence

of three-rooted mandibular first molars, combined with

the possibility of misinterpretation of extra distolingual

root aberrations during root canal treatment.

Orthodontic implications

Other clinical difficulties resulting from distolingual

root would relate to orthodontic procedures, where the

extra root would render movement difficult.[10,49] It is

also hypothesized that the presence of extra root (RE)

adds to the stability of molars by providing an increased

surface area of attachment to the alveolus.[10,49]

Since it is not known whether abnormal root

configurations like three-rooted molar affect, the normal

exfoliation of the primary teeth, it is unclear whether

these anomalous teeth present orthodontic problems.

RE as a contributing factor to localized

periodontitis

According to Huang et al.[48] RE may be a contributory

factor in localized periodontal destruction. In their

study, patients with a distolingual root demonstrated

significantly greater probing depth and attachment

loss at distolingual sites than at distobuccal sites.

Molars with RE demonstrated greater loss around the

100

distolingual root compared with molars that had only

one distal root.

Forensic odontology

The presence of a third root, whether primary or

permanent may have forensic value for identifying

people of the Mongoloid origin.[5,49]

Discussion

The present article reports 15 extra roots in mandibular

molars of Indian children that were diagnosed using both

periapical radiographs (12 cases) and extracted teeth

(three cases). There have been several reports of the

occurrence of supernumerary roots in both permanent

and primary mandibular molars of different populations.

But studies of the prevalence of extra root variants in

Indian population are few in number.[14] Garg et al.[51]

have found 5% prevalence of three-rooted permanent

mandibular first molars in Indian adult patients.

In the present report, the number of three-rooted

mandibular molars including both primary and permanent

did not show difference with gender, which is consistent

with findings of other reports of permanent first molars

done in Hong Kong Chinese,[22] Taiwanese,[5] and

Singapore Chinese[10] and Japanese patients.[9,52] However,

some studies found male predominance.[36-39] Only four

cases of three-rooted primary molars were diagnosed

with remaining 11 cases of extra roots in permanent

first molars. This finding is in accordance with the results

suggesting that three-rooted mandibular first molars are

rarer in primary than permanent dentition.[14,35]

Most of the three-rooted mandibular fist molars in

Asians show a bilateral occurrence.[5,10,36,39] Only one

patient of our report showed bilateral occurrence of

extra root in primary mandibular first molar. The

incidences of bilateral occurrence were 67.8%, 64.0%,

and 39.3% for the first permanent, second primary,

and first primary molars, respectively as shown in one

study.[35] Sabala et al.[53] reported that aberrant root

morphology in a given tooth is observed with varying

frequency in the corresponding contra lateral tooth, but

it is not found in mandibular primary first molars with

three roots. Tu et al.[34] found bilateral occurrence of

primary first molars (17.67%) less than the report by

Song et al.[35] Both Taiwanese and Korean populations

appeared much more unilateral occurrence of threerooted primary mandibular first molars than permanent

mandibular first molars do.[34,35]

JOURNAL OF INDIAN SOCIETY OF PEDODONTICS AND PREVENTIVE DENTISTRY | Apr - Jun 2012 | Issue 2 | Vol 30 |

[Downloadedfreefromhttp://www.jisppd.comonWednesday,October24,2012,IP:110.138.184.158]||ClickheretodownloadfreeAndroidapplicationforthisjour

Nagaveni, et al.: Supernumerary roots in mandibular molars

The first morphologic classification of distolingual root

(RE) was established by De Moore et al.[2] who examined

extracted first molar and divided morphologic features

of third root into three types according to the pattern

of their curvature. They found two cases of type I, five

cases of type II, and 11 cases of type III. In contrast

to this, our study found 12 cases of type I, 1 case of

typeII, and 2 cases of type III. In case of mesiobuccal

root (RP), Carlsen and Alexandersen[3] found five cases

of type A and none of type B in the total 203 permanent

molars examined. Our study found only two cases of

type A mesiobuccal root.

Association of extra roots with adjacent molars was

not seen in none of the reported cases. One study done

by Song et al.[35] showed the relationship of extra roots

with adjacent molars and have suggested that when

an additional root was present in a primary molar, the

probability of the posterior adjacent molar also having an

additional root was greater than 94.3% that help to predict

the presence of an extra root in molars posterior to it.

For successful root canal treatment it is necessary to

locate all roots and canals as unfilled canals remain a nidus

for infection and can compromise treatment outcome.[31]

This was evident in three of our cases due to undiagnosed

and untreated third root [Figure 1]. Therefore, to make

RE/RP evident and for accurate diagnosis, a second

radiograph should be taken from a more mesial or distal

angle and clinician should be aware of the existence of

additional roots in molars of both dentition.

The limitation of the present report is that it provides

information about only 15 cases of extra roots in

mandibular molars. From this it is difficult to state

precisely the prevalence of extra roots in mandibular

molars of Indian children. Therefore, further studies

involving large samples are highly essential to assess

the prevalence of additional roots in group of children

from Indian origin which will add more knowledge to

the existing literature.

Conclusion

Dentists should take into account the prevalence of

extra root variants in both primary and permanent

mandibular first molars among children during their

routine endodontic and exodontic procedures. Before

initiating root canal treatment or extraction, clinician

should utilize two periapical radiographs (taken at

different angles) to confirm the presence of an extra

root in order to achieve the successful treatment.

References

1. Carabelli G. Systematisches Handbuch der Zahnheikunde. 2nd

ed. Vol. 114. Vienna: Braumuller and Seidel; 1844.

2. De Moor RJ, Deroose CA, Calberson FL. The radix entomolaris

in mandibular first molars: An endodontic challenge. Int Endod

J 2004;37:789-99.

3. Carlsen O, Alexandersen V. Radix paramolaris in permanent

mandibular molars: Identification and morphology. Scand J Dent

Res 1991;99:189-95.

4. Bolk L. Bemerkungen u ber Wurzelvariationen am menschlichen

unteren Molaren. Zeiting fur Morphologie Anthropologie

1915;17;605-10.

5. Tu MG, Tsai CC, Jou MJ, Chen WL, Chang YF, Chen SY,

etal. Prevalence of three-rooted mandibular first molars among

Taiwanese individuals. J Endod 2007;33:1163-6.

6. Gulabivala K, Opasanon A, Ng YL, Alavi A. Root and canal

morphology of Thai mandibular molars. Int Endod J 2002;35:56-62.

7. Gulabivala K, Aung TH, Alavi A, Ng YL. Root and canal

morphology of Burmese mandibular molars. Int Endod J

2001;34:359-70.

8. Yew SC, Chan K. A retrospective study of endodontically

treated mandibular first molars in a Chinese population. J Endod

1993;19:471-3.

9. Ferraz JA, Pecora JD. Three rooted mandibular molars in

patients of Mongolian, Caucasian and Negro origin. Braz Dent

J 1992;3:113-7.

10. Loh HS. Incidence and features of three-rooted permanent

mandibular molars. Aust Dent J 1990;35:437-7.

11. Jones AW. The incidence of the three-rooted lower first

permanent molar in Malay people. Singapore Dent J 1980;5:15-7.

12. Hochstetter RL. Incidence of trifurcated mandibular first

permanent molars in the population of Guam. J Dent Res

1975;54:1097.

13. Laband F. Two years dental school work in British North Borneo:

Relation of diet to dental caries among natives. J Am Dent Assoc

1941;28:992-8.

14. Tratman EK. Three-rooted lower molars in man and their racial

distribution. Br Dent J 1938;64:264-74.

15. Iwaka Y. Three-dimensional observation of the pulp cavity

of mandibular first molars by micro-CT. J Oral Biosci

2006;48;94-102.

16. Jung M, Lommel D, Klimek J. The imaging of root canal

obturation using micro-CT. Int Endod J 2005;38:617-26.

17. Mannocci F, Peru M, Sherriff M, Cook R, Pitt Ford TR. The

isthmuses of the mesial root of mandibular molars: A microcomputed tomographic study. Int Endod J 2005;38:558-63.

18. Tu MG, Huang HL, Hsue SS, Hsu JT, Chen SY, Jou MJ, et al.

Detection of permanent three-rooted mandibular first molars

by cone-beam computed tomography imaging in Taiwanese

individuals. J Endod 2009;35:503-7.

19. Matherne RP, Angelopoulos C, Kulild JC, Tira D. Use of conebeam computed tomography to identify root canal systems in

vitro. J Endod 2008;34:87-9.

20. Taylor C, Geisler TM, Holden DT, Schwartz SA, Schinler WG.

Endodontic applications of cone-beam volumetric tomography.

J Endod 2007;33:1121-32.

21. Song JS, Choi HJ, Jung IY, Jung HS, Kim SO. The prevalence

and morphologic classification of distolingual roots in

the mandibular molars in a Korean population. J Endod

2010;36:653-7.

22. Walker RT, Quackenbush LE. Three-root lower first permanent

molar in Hong-Kong Chinese. Br Dent J 1985;159:298-9.

JOURNAL OF INDIAN SOCIETY OF PEDODONTICS AND PREVENTIVE DENTISTRY | Apr - Jun 2012 | Issue 2 | Vol 30 |

101

[Downloadedfreefromhttp://www.jisppd.comonWednesday,October24,2012,IP:110.138.184.158]||ClickheretodownloadfreeAndroidapplicationforthisjour

Nagaveni, et al.: Supernumerary roots in mandibular molars

23. Sperber GH, Moreau JL. Study of the number of roots and canals

in Senegalese first permanent mandibular molars. Int Endod J

1998;31:112-6.

24. Pedersen PO. The East Greenland Eskimo dentition. Numerical

variations and anatomy. A contribution to comparative ethnic

odontography. Copenhagen: Meddeleser om Gronland; 1949. p.

14-144.

25. Turner CG 2nd. Three-rooted mandibular first permanent

molars and the question of American Indian origins. Am J Phys

Anthropol 1971;34;229-41.

26. Curzon ME, Curzon AJ. Three-rooted mandibular molars in the

Keewatin Eskimo. J Can Dent Assoc (Tor) 1971;37:71-2.

27. Reichart PA, Metah D. Three-rooted permanent mandibular first

molars in the Thai. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1981;9:191-2.

28. Curzon ME. Three-rooted mandibular permanent molars in

English Caucasians. J Dent Res 1973;52;181.

29. Falk WV, Bowers DF. Bilateral three-rooted mandibular

first primary molars: Report of case. ASDC J Dent Child

1983;50:136-7.

30. Badger GR. Three-rooted mandibular first primary molar. Oral

Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1982;53:547.

31. Curzon ME, Curzon JA. Three-rooted mandibular molars in

the Keewatin Eskimo: Its relationship to the prevention and

treatment of caries. J Can Dent Assoc 1972;38;152.

32. Jorgensen KD. The deciduous dentition. A descriptive

and comparative anatomical study. Acta Odontol Scand

1956;14:1-202.

33. Sugiyama K, Tanaka H, Hitomi K, Kurosu K. A study on the

three roots in the mandibular first deciduous molar. Jap J Pediat

Dent 1976;14:241-6.

34. Tu MG, Liu JF, Dai PW, Chen SY, Hsu JT, Huang H. Prevalence

of three-rooted primary mandibular first molars in Taiwan. J

Formos Med Assoc 2010;109:69-74.

35. Song JS, Kim SO, Choi BJ, Choi HJ, Son HK, Lee JH. Incidence

and relationship of an additional root in the mandibular first

permanent molar and primary molars. Oral Surg Oral Med

Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2009;107:e56-60.

36. Liu JF, Dai PW, Chen SY, Huang HL, Hsu JT, Chen WL, etal.

Prevalence of 3-rooted primary mandibular second molars among

Chinese patients. Pediatr Dent 2010;32:123-6.

37. de Souza-Freitas JA, Lopes ES, Casati-Alvares L. Anatomic

variations of lower first permanent molar roots in two ethnic

groups. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1971;31:278-8.

38. Somogyi-Csizmazia W, Simons AJ. Three-rooted mandibular

first permanent molars in Alberta Indian children. J Can Dent

Assoc 1971;37:105-6.

39. Steelman R. Incidence of an accessory distal root on mandibular

first permanent molars in Hispanic children. ASDC J Dent Child

1986;53:122-3.

40. Quackenbush LE. Mandibular molar with three distal root

canals. Endod Dent Traumatol 1986;2:48-9.

41. Visser JB. Beitrag zur Kenntnis der menschlichen Zahnwurzelformen. Hilversum Rotting 1948;49-72.

42. Curzon ME. Miscegenation and the prevalence of three-rooted

mandibular first molars in Baffin Eskimo. Community Dent Oral

Epidemiol 1974;2:130-1.

43. Carlsen O, Alexandersen V. Radix entomolaris: Identification

and morphology. Scand J Dent Res 1990;98:363-73.

44. Calberson FL, De Moor RJ, Deroose CA. The radix entomolaris

and paramolaris: Clinical approach in endodontics. J Endod

2007;33:58-63.

45. ACs G, Pokala P, Cozzi E. Shovel incisors, three-rooted molars,

talon cusp, and supernumerary tooth in one patient. Pediatr

102

Dent 1992;14:263-4.

46. Winkler MP, Ahmad R. Multirooted anomalies in the

primary dentition of native Americans. J Am Dent Assoc

1997;128:1009-11.

47. Ingle JI, Heithersay GS, Hartwell GR. Endodontic diagnostic

procedures. In: Ingle JI, Bakland LF, editors. Endodontics. 5th

ed. London: B.C. Decker Inc.; 2002. p. 203-58.

48. Huang RY, Lin CD, Lee MS, Yeh CL, Shen EC, Chiang CY,

etal . Mandibular disto-lingual root: A consideration in

periodontal therapy. J Periodontol 2007;78;1485-90.

49. Mayhall JT, Three-rooted deciduous mandibular second molars.

Clinical, forensic and theoretical implications. J Can Dent Assoc

1971;47:319-21.

50. Salehrabi R, Rotstein I. Endodontic treatment outcomes in a

large patient population in the USA: An epidemiological study.

J Endod 2004;30:846-50.

51. Garg AK, Tewari RK, Kumar A, Hashmi SH, AgrawalN,

MishraSK. Prevalence of three-rooted mandibular permanent first

molars among the Indian population. J Endod 2010;36:1302-6.

52. Harada Y, Tomino S, Ogawa K, Wada T, Mori S, Kobayashi S,

et al. Frequency of three-rooted mandibular first molars. Survey

of X-ray photographs. Shika Kiso Igakkai Zasshi 1989;31:13-8.

53. Sabala CL, Benenati FW, Neas BR. Bilateral root or root canal

aberrations in a dental school patient population. J Endod

1994;20:38-42.

54. Taylor AR. Variations in the human tooth form as met with

isolated teeth. J Anat Physiol 1899;33:268-72.

55. Campbell TD. Dentition and the palate of the Australian

Aboriginal. Adelaide: Keith Sheridan Foundation, Adelaide

Publication 2; 1925.

56. Drennan MR. The dentition of the Bushmen tribe. Annals of

South African Museum 1929;24:61-87.

57. Shaw JC. The teeth, the bony palate and the mandible in

Bantu Races of South Africa. London, UK: John Bale, Sons &

Danielson; 1931.

58. Skidmore AE, Bjorndahl AM. Root canal morphology of the

human mandibular first molar. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol

1971;32:778-84.

59. Walker RT. Root form and canal antomy of mandibular first molars

in a southern Chinese population. Dent Traumatol 1988;4:19-22.

60. Younes SA, Al-Shammery AR, El-Angbawi AF. Three-rotoed

permanent mandibular first molars of Asian and black groups in

the Middle East. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1990;69:102-5.

61. Schafer E, Breuer D, Janzen S. The prevalence of three-rooted

mandibular permanent first molars in a German population. J

Endod 2009;35:202-5.

62. Yang Y, Zhang LD, Ge JP, Zhu YQ. Prevalence of 3-rooted first

permanent molars among a Shanghai Chinese population. Oral

Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2010;110:e98-100.

63. Peiris R, Takahashi M, Sasaki K, Kanazawa E. Root and canal

morphology of permanent mandibular molars in Sri Lankan

population. Odontology 2007;95:16-23.

64. Huang RY, Cheng WC, Chen CJ, Lin CD, Lai TM, ShenEC,

et al. Three-dimensional analysis of the root morphology of

mandibular first molars with distolingual roots. Int Endod J

2010;43:478-84.

How to cite this article: Nagaven NB, Umashankara KV. Radix

entomolaris and paramolaris in children: A review of the literature.

J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent 2012;30:94-102.

Source of Support: Nil, Conflict of Interest: None declared.

JOURNAL OF INDIAN SOCIETY OF PEDODONTICS AND PREVENTIVE DENTISTRY | Apr - Jun 2012 | Issue 2 | Vol 30 |

Potrebbero piacerti anche

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryDa EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Da EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Valutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceDa EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItDa EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingDa EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaDa EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeDa EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesDa EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreDa EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyDa EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyValutazione: 3.5 su 5 stelle3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersDa EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeDa EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerDa EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnDa EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceDa EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureDa EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureValutazione: 4.5 su 5 stelle4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealDa EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (74)

- Happiest Refugee Coursework 2013Documento10 pagineHappiest Refugee Coursework 2013malcrowe100% (2)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Da EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Valutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaDa EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaValutazione: 4 su 5 stelle4/5 (45)

- Motor BookDocumento252 pagineMotor BookKyaw KhNessuna valutazione finora

- 04 DosimetryDocumento104 pagine04 DosimetryEdmond ChiangNessuna valutazione finora

- HypnosisDocumento18 pagineHypnosisNiNis Khoirun Nisa100% (1)

- Norman K. Denzin - The Cinematic Society - The Voyeur's Gaze (1995) PDFDocumento584 pagineNorman K. Denzin - The Cinematic Society - The Voyeur's Gaze (1995) PDFjuan guerra0% (1)

- Bagi CHAPT 7 TUGAS INGGRIS W - YAHIEN PUTRIDocumento4 pagineBagi CHAPT 7 TUGAS INGGRIS W - YAHIEN PUTRIYahien PutriNessuna valutazione finora

- SWAMINATHAN Ajanta RhapsodyDocumento227 pagineSWAMINATHAN Ajanta RhapsodyRoberto E. García100% (1)

- Lesson Plan Ordinal NumbersDocumento5 pagineLesson Plan Ordinal Numbersapi-329663096Nessuna valutazione finora

- JIndianSocPedodPrevDent302179-1553084 041850Documento4 pagineJIndianSocPedodPrevDent302179-1553084 041850NiNis Khoirun NisaNessuna valutazione finora

- Self Etching Adhesive On Intact Enamel: Devarasa GM, Subba Reddy VV, Chaitra NLDocumento6 pagineSelf Etching Adhesive On Intact Enamel: Devarasa GM, Subba Reddy VV, Chaitra NLNiNis Khoirun NisaNessuna valutazione finora

- Price List DENTAL JAYA Dental SupplyDocumento24 paginePrice List DENTAL JAYA Dental SupplyNiNis Khoirun Nisa100% (3)

- Proac Studio 100: Monitor Level Performance From An Established Compact DesignDocumento2 pagineProac Studio 100: Monitor Level Performance From An Established Compact DesignAnonymous c3vuAsWANessuna valutazione finora

- Cisco Nexus 7000 Introduction To NX-OS Lab GuideDocumento38 pagineCisco Nexus 7000 Introduction To NX-OS Lab Guiderazzzzzzzzzzz100% (1)

- Best S and Nocella, III (Eds.) - Igniting A Revolution - Voices in Defense of The Earth PDFDocumento455 pagineBest S and Nocella, III (Eds.) - Igniting A Revolution - Voices in Defense of The Earth PDFRune Skjold LarsenNessuna valutazione finora

- Test Bank Bank For Advanced Accounting 1 E by Bline 382235889 Test Bank Bank For Advanced Accounting 1 E by BlineDocumento31 pagineTest Bank Bank For Advanced Accounting 1 E by Bline 382235889 Test Bank Bank For Advanced Accounting 1 E by BlineDe GuzmanNessuna valutazione finora

- Stability TestDocumento28 pagineStability TestjobertNessuna valutazione finora

- Being Agile. Staying Resilient.: ANNUAL REPORT 2021-22Documento296 pagineBeing Agile. Staying Resilient.: ANNUAL REPORT 2021-22PrabhatNessuna valutazione finora

- Math Habits of MindDocumento12 pagineMath Habits of MindAzmi SallehNessuna valutazione finora

- BraunDocumento69 pagineBraunLouise Alyssa SazonNessuna valutazione finora

- Estocell - Data Sheet - 14-07-06Documento2 pagineEstocell - Data Sheet - 14-07-06LeoRumalaAgusTatarNessuna valutazione finora

- 50 Interview Question Code Galatta - HandbookDocumento16 pagine50 Interview Question Code Galatta - HandbookSai DhanushNessuna valutazione finora

- BROMINE Safety Handbook - Web FinalDocumento110 pagineBROMINE Safety Handbook - Web Finalmonil panchalNessuna valutazione finora

- CompTIAN10 004Documento169 pagineCompTIAN10 004Ian RegoNessuna valutazione finora

- Pavlishchuck Addison - 2000 - Electrochemical PotentialsDocumento6 paginePavlishchuck Addison - 2000 - Electrochemical PotentialscomsianNessuna valutazione finora

- Tutorial Letter 101/0/2022: Foundations in Applied English Language Studies ENG1502 Year ModuleDocumento17 pagineTutorial Letter 101/0/2022: Foundations in Applied English Language Studies ENG1502 Year ModuleFan ele100% (1)

- PCNSE DemoDocumento11 paginePCNSE DemodezaxxlNessuna valutazione finora

- Climate Declaration: For White Corex PlasterboardDocumento1 paginaClimate Declaration: For White Corex PlasterboardAbdullah BeckerNessuna valutazione finora

- Marshall Mix Design (Nptel - ceTEI - L26 (1) )Documento7 pagineMarshall Mix Design (Nptel - ceTEI - L26 (1) )andrewcwng0% (1)

- 1939 - Hammer - Terrain Corrections For Gravimeter StationsDocumento11 pagine1939 - Hammer - Terrain Corrections For Gravimeter Stationslinapgeo09100% (1)

- Arabian Choice General Trading Co. LLCDocumento1 paginaArabian Choice General Trading Co. LLCjaanNessuna valutazione finora

- Charging Station For E-Vehicle Using Solar With IOTDocumento6 pagineCharging Station For E-Vehicle Using Solar With IOTjakeNessuna valutazione finora

- Store Docket - Wood PeckerDocumento89 pagineStore Docket - Wood PeckerRakesh KumarNessuna valutazione finora

- D4462045416 PDFDocumento3 pagineD4462045416 PDFSamir MazafranNessuna valutazione finora

- A Software Architecture For The Control of Biomaterials MaintenanceDocumento4 pagineA Software Architecture For The Control of Biomaterials MaintenanceCristian ȘtefanNessuna valutazione finora